Regenerating nerve fiber innervation of extraocular muscles and motor functional changes following oculomotor nerve injuries at different sites**☆○

Wenchuan Zhang, Massimiliano Visocchi, Eduardo Fernandez, Xuhui Wang, Xinyuan Li, Shiting Li

1Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200092, China

2Istituto di Neurochirurgia-Policlinico Agostino Gemelli, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome 00185, Italy

Regenerating nerve fiber innervation of extraocular muscles and motor functional changes following oculomotor nerve injuries at different sites**☆○

Wenchuan Zhang1, Massimiliano Visocchi2, Eduardo Fernandez2, Xuhui Wang1, Xinyuan Li1, Shiting Li1

1Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200092, China

2Istituto di Neurochirurgia-Policlinico Agostino Gemelli, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome 00185, Italy

In the present study, the oculomotor nerves were sectioned at the proximal (subtentorial) and distal (superior orbital fissure) ends and repaired. After 24 weeks, vestibulo-ocular reflex evaluation confirmed that the regenerating nerve fibers following oculomotor nerve injury in the superior orbital fissure had a high level of specificity for innervating extraocular muscles. The level of functional recovery of extraocular muscles in rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group was remarkably superior over that in rats undergoing oculomotor nerve injuries at the proximal end (subtentorium). Horseradish peroxidase retrograde tracing through the right superior rectus muscle showed that the distribution of neurons in the nucleus of the oculomotor nerve was directly associated with the injury site, and that crude fibers were badly damaged. The closer the site of injury of the oculomotor nerve was to the extraocular muscle, the better the recovery of neurological function was. The mechanism may be associated with the aberrant number of regenerated nerve fibers passing through the injury site.

oculomotor nerve; functional reconstruction; specific innervations; injury sites; neural regeneration

lNTRODUCTlON

The functional reconstruction of nerves after oculomotor nerve injuries is difficult for neurosurgeons to achieve. Parasympathetic function recovers well after oculomotor nerve injury, but motor function of extraocular muscles is not improved and abnormal activities of extraocular muscles may occur[1-4]. This may be caused by different repair methods or it may result from the effects of non-specific innervation of nerve fibers on extraocular muscle function. The present study aimed to explore the potential mechanism underlying functional repair after oculomotor nerve injuries by sectioning the oculomotor nerves of rats. Injuries were matchedin situand fixed through the subtentorium and superior orbital fissure, and the degree of extraocular muscle recoveries was evaluated based on the vestibulo-ocular reflex. In addition, the histology and anatomy of the oculomotor nerve were observed.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of experimental animals

A total of 60 Sprague-Dawley rats were selected. The oculomotor nerves were sectioned either at the subtentorium (subtentorial injury group;n= 24) and at the superior orbital fissure (superior orbital fissure injury group;n= 24), and then immediately repaired by end-to-end alignment and fixed with bio-gum. Another six rats (three sectioned at the subtentorium and three sectioned at the superior orbital fissure) were not repaired as injury controls. The remaining six rats served as normal controls. Three rats died during surgery; two of these died due to postoperative hemorrhage (sectioned at the subtentorium) and one died from postoperative infection (sectioned at the superior orbital fissure).

The mortality rate was 5%. Therefore, 57 rats were included in the final analysis.

Somatic movement functions of oculomotor nerves were better in the superior orbital fissure injury group than in the subtentorial injury group

Twenty-four weeks after surgery, the averaged horizontal vestibulo-ocular reflex (HVOR) and vertical vestibulo-ocular reflex (VVOR) reached 91% and 87% of the normal values, respectively, in rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group. These reflexes reached 26% and 21% of the normal values, respectively, in rats in thesubtentorial injury group (P< 0.01). HVOR and VVOR were all zero in rats in the injury control group. Abnormal ocular movement was observed in the subtentorial injury group. That is, in the presence of stimulation in the horizontal direction, their eyeballs moved vertically, while when exposed to stimulation in the vertical direction, their eyeballs moved horizontally. No abnormal ocular movement was observed in rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group. Regenerating nerve fibers following oculomotor nerve injury at the superior orbital fissure had a high specificity for innervating extraocular muscles.

The level of functional recovery of extraocular muscles in rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group was remarkably superior over that in rats in the subtentorial injury group.

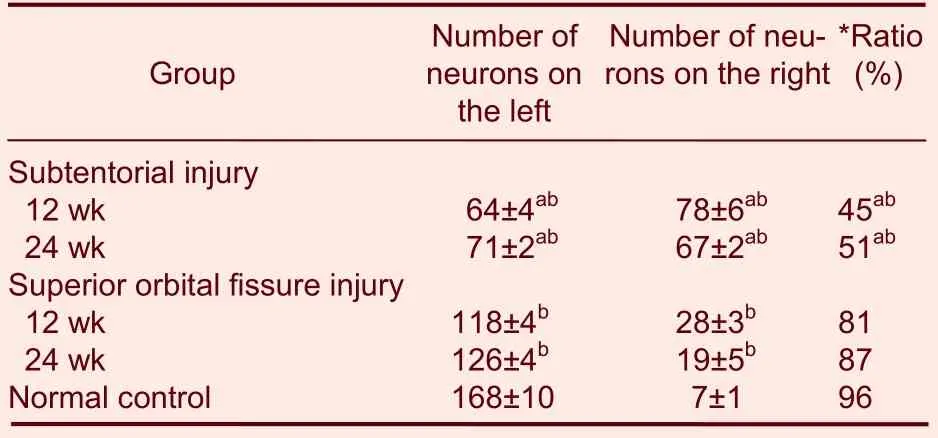

Number of neurons in the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus in the superior orbital fissure injury group was greater than that in the subtentorial injury group

At 1, 12, and 24 weeks post-injury, rats were anesthetized and injected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) as a retrograde tracerviathe right superior rectus muscle to trace the distribution of neurons in the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus. Following 3, 3', 5, 5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) coloration, blue neurons were observed in the midbrain (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of neurons within the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus, retrogradely labeled by injection of horseradish peroxidase (3, 3', 5,

There were significantly fewer neurons in the midbrain oculomotor nerve nuclei of rats with oculomotor nerve injuries compared with normal rats. In particular, the number of contralateral neurons was significantly lower than that in normal rats (P< 0.01), but the number of contralateral neurons in the superior orbital fissure injury group was significantly greater than that in the subtentorial injury group (P< 0.05; Table 1).

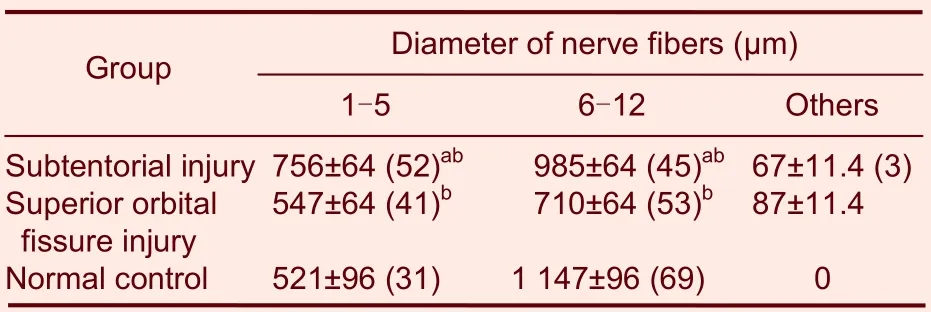

Nerve fiber and myelin sheath regeneration following injury repair

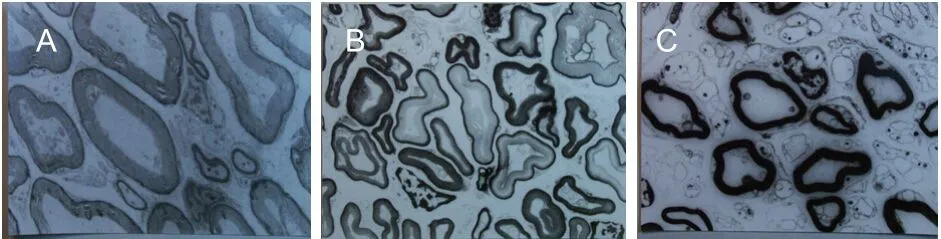

Normal oculomotor nerves are composed of two kinds of nerve fibers, with diameters of 1-5 μm and 6-14 μm. In normal rats, the total number of oculomotor nerve fibers was 1 668 ± 64, of which the number of nerve fibers with a diameter of 6-14 μm and an average myelin sheath thickness of 1.63 ± 0.18 μm was 1 147 ± 96, accounting for 69% of all nerve fibers. The number of nerve fibers with a diameter of 1-5 μm and an average myelin sheath thickness of 0.62 ± 0.07 μm was 521 ± 96, accounting for 31% of all nerve fibers. At 24 weeks post-injury, the number and percentage of nerve fibers with a diameter of 6-14 μm were decreased, while those of nerve fibers with a diameter of 1-5 μm were increased (Table 2, Figure 2).

Table 1 Number of neurons within the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus

Table 2 Distribution of the nerve fibers in each group 24 weeks after intervention

DlSCUSSlON

Extensive studies in animals have been conducted to probe the potential mechanisms underlying functional reconstruction after oculomotor nerve injuries. Different results have been obtained regarding the degree of motor function recoveries of extraocular muscles after regeneration of oculomotor nerves[5-7]. However, the reason for the abnormal movement of extraocular muscles remains poorly understood. In the current study, we sectioned oculomotor nerves at their proximal end (subtentorium) and their distal end (at the superior orbital fissure), separately, in adult rats, and repaired the injuries immediately. Somatic motor function of oculomotor nerves was evaluated 24 weeks after operation by measuring the amplitudes of horizontal and vertical movements of extraocular muscles through the vestibulo-ocular reflex. In addition, histology of sections of regenerative oculomotor nerve tissues was observed 16-24 weeks after operation. HRP was injected into the superior rectus muscle on the side of injuries to retrogradely trace the distribution of neurons innervating extraocular muscles in the midbrain, and to investigate the relationship between specific innervations of extraocular muscles by regenerating nerve fibers and the motor functions of extraocular muscles.

Figure 2 Ultrastructure of oculomotor nerve fibers in each group (transmission electron microscope, × 600).

Our results showed that the functional recovery of the extraocular muscles of rats whose oculomotor nerves were sectioned at the superior orbital fissure, 24 weeks after the operation, was much better than that of the rats whose oculomotor nerves were sectioned beneath the tentorium. In addition, there was no abnormal movement in their eyeballs. Motor function recovery in the extraocular muscles of rats in the subtentorial injury group was poor, and ocular vertical movement appeared following stimulation in a horizontal direction, and horizontal movement happened following stimulation in a vertical direction. The closer the site of injury of oculomotor nerves was to the target organ, the better was the recovery of nervous function. However, the reason for this remains unclear. Some studies[8-10]have suggested that this may be the result of a decrease in the number of motoneurons in the oculomotor nerves in the midbrain after nerve injuries, while other researchers[11-13]attributed the relatively poor recovery of nervous functions to the redistribution of neurons within the oculomotor nerve nucleus in the midbrain after nerve injuries. In addition, the poor specificity for re-innervating target organs by nascent nerve fibers, which resulted in a relatively poor recovery of nervous functions, may also contribute[14-16].

HRP injection was used in this study to retrogradely trace the distributions of motoneurons innervating the superior rectus muscle in the midbrain through axoplasmic transport of regenerating nerve fibers. The results showed that, compared with normal rats, there was a remarkable decrease in the number of neurons in the midbrain in rats with either subtentorial or superior orbital fissure injuries, but that there was no significant difference in terms of the number of neurons between the subtentorial and superior orbital fissure injury groups. Therefore, we assume that the decrease in the number of neurons innervating oculomotor nerves might not be the main reason for the difference in the recoveries of oculomotor nerve functions in rats in the subtentorial and superior orbital fissure injury groups. Regarding the decrease in the number of neurons after nerve injuries, some researchers believe that injury information is fed back to neurons, resulting in neuronal apoptosis[17-19]. However, no karyopyknosis of cells or signs of apoptosis of neurons in the midbrain, such as phagotrophy of inclusion bodies, increases in lysosomes, and shrinkage or contraction of cell membranes, nor any apoptosis corpuscle, was observed in the present study.

We believe that loss of nervous innervations by extraocular muscles due to sectioning of oculomotor nerves led to their shrinkage, thus making it difficult to label the motoneurons in the midbrain. Therefore, a decrease in the number of labeled neurons is not a key factor governing the degree of nervous function recovery. Through retrograde tracing, the distribution of stained motoneurons innervated by oculomotor nerves in the oculomotor nerve nucleus of the bilateral midbrain was determined: 96% of the nerve fibers innervating extraocular muscles in normal rats were sent out by the contralateral midbrain motoneurons. In rats in the subtentorial injury group, only 45-51% of the nerve fibers innervating the superior rectus muscle were sent out by the contralateral midbrain neurons. In rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group, 81-87% of the nerve fibers innervating the superior rectus muscle were sent out by the contralateral midbrain neurons. The distribution of neurons in the midbrain was similar to that in normal rats. This could be attributed to a better recovery of oculomotor nerve functions in rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group. Therefore, we conjecture that the redistribution of neurons in the midbrain innervating extraocular muscles must be a critical factor affecting nervous function recoveries. Results from previous studies have indicated that after sectioning of oculomotor nerves, Wallerian degenerations occur in all axons on both the proximal and distal sides of the injured nerves. The neurons in the midbrain continuously sent out regenerating nerve fibers, which regenerate in the form of budding from the proximal to the distal stumps, and reinnervate target organs. During this period, some nerve fibers enter the wrong Bands of Büngner, resulting in abnormal innervations of the extraocular muscles. As a result, motor functions did not recover well, and abnormal movements of extraocular muscles appeared. In the superior orbital fissure injury group, because the site of nerve injury was close to the target organ, the possibilities of the regenerating nerve fibers entering the wrong endoneurial tube were low, and the majority of the regenerating nerve fibers could still specifically innervate their original target organs. Therefore, a better functional recovery of extraocular muscles could be achieved. Retrograde tracing and labeling the distribution of neurons innervating the superior rectus muscle by HRP injection also indirectly confirmed that the more similar the distribution of motoneurons within the oculomotor nerve nucleus in the midbrains of rats with nerve injuries is to the normal distribution (81-87% from the contralateral side), the less aberrant the regenerating nerve fibers are. As a result, correct reinnervation of extraocular muscles by regenerating nerve fibers is one factor affecting nervous function recovery.

The oculomotor nerve contains two kinds of fibers: thick and thin fibers, distributed in a bimodal fashion. The thick fibers mainly dominate the extraocular muscle, and the thin fibers dominate the pupil sphincter and ciliary muscle. Following nerve injury, degeneration of thick fibers is more serious, and the subsequent regeneration is slower and less specific. In contrast, degeneration of the thin fibers after injury is relatively mild, and the subsequent regeneration is quicker and better. This may account for the fact that functional recovery of parasympathetic nerve fibers is better and occurs sooner. After nerve injury, the number of nerve fibers within the oculomotor nerve is significantly increased, especially at the distal end. New axons are mainly small fibers. However, an increase in the number of new fibers does not always indicate a better functional recovery, because the anatomical basis of functional recovery is specific innervations of the target organ by new fibers.

In conclusion, determining how to prevent aberrant regeneration and incorrect reinnervation of target organs after oculomotor nerve injuries will be critical for promoting recovery of neurological function.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized, controlled, animal experiment.

Time and setting

This study was performed at the Animal Experimental Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical School, China from January 2007 to June 2009.

Materials

A total of 60 male rats, aged 8 months, weighing 250-300 g, were provided by Shanghai BK Co., Ltd. (No. SCXK (Shanghai) 2003-009); permit No. SYXK (Shanghai) 2003-0047). Protocols were performed in accordance with theGuidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China[20].

Methods

Establishment of proximal and distal oculomotor nerve injury models

After a bony window was made, the dura mater was carefully cut open and sutured to the temporalis. Using an unobvious sylvian fissure, which was identifiable by the naked eye as a mark, the oculomotor nerve, which was located in the posterior cavernous sinus and free in the cerebelli tentorium, could be identified by lightly lifting the lobus pyriformis with a narrow cerebral spatula under a microscope[1]. The oculomotor nerves of 24 rats in the subtentorial injury group were sectioned at the subtentorium, end-to-end aligned and fixed with bio-gum. The oculomotor nerves of 24 rats in the superior orbital fissure injury group were transected at the superior orbital fissure using the same method. The nerves of rats in the injury control group were stumped by bipolar electro-coagulation with the proximal end turned backward. The nerves of the normal control rats were not injured.

Evaluation of the function of oculomotor nerves using vestibulo-ocular reflex

The vestibulo-ocular reflex was measured once a week from the 1stweek to the 24thweek after nerve injuries[21-22]. Etherized animals were placed on a reflex machine and measurement was conducted in both the horizontal and vertical axes, with the amplitude of the shaker (WISBiomed, San Mateo, CA, USA) set to ± 100 and the stimulus frequency set to 0.02-0.40 Hz. Corneal anesthesia was performed with 0.4% procaine. The infrared emission tube (Dongguan Zhangmutou Jincheng Electronic Co., Ltd., Dongguan, Guangdong Province, China) was settled near the cornea. Infrared light was emitted from X-axis and Y axis. The ratio of the maximal speed of eye movements to the maximal rotation speed of the shaking table was calculated.

Distribution of neurons within the oculomotor nerve nucleus traced by HRP injection

The animals were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of diazepam (2 mg/100 g) and intramuscular injection of ketalar (4 mg/100 g) in the 1st, 12thand 24thweeks after intervention of oculomotor nerves. The superior rectus muscle was exposed through the dextral ocular trans-conjunctival approach and neurons within the oculomotor nerve nucleus were retrogradely labeled by intrathecal injection of HRP (0.85 μL; J&K Scientific Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Observation of neurons and oculomotor nerve fibersin the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus using TMB staining

Animals were anesthetized and fixed for 48 hours after injection of HRP by perfusion through heart with normal saline, 1.25% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaric dialdehyde and 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer. Samples at the level of the midbrain oculomotor nerve nucleus level and at 5 mm from each of the distal end and the proximal end of the injury site of oculomotor nerve were harvested. Frozen sections (50 μm) were continuously prepared after samples had been soaked in 30% sucrose buffer for 30 minutes. TMB (J&K Scientific Ltd.) staining was performed by the modified Angelov method[23-25].

Structures of neurons and neural axons were observed under light (Martin Microscope Company, Easley, SC, USA) and electron microscopes (Martin Microscope Company). The number of the nerve fibers, and the number and diameters of the neural axons were calculated. In addition, the distribution of the midbrain neurons labeled by HRP, the diameters of the nerve fibers, and the thickness of the myelin sheath were analyzed using a computer-aided image analysis system (WISBiomed, San Mateo, CA, USA). The Vidas Rel. 2.1 image analysis system (WISBiomed) was used to analyze images.

Statistical analysis

Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance, Student’st-test or chi-square test, using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A value ofP< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions: Massimiliano Visocchi and Xuhui Wang had full access to all data and participated in data collection and analysis. Xinyuan Li participated in data collection. Eduardo Fernandez and Xuhui Wang participated in data analysis and interpretation. Wenchuan Zhang and Shiting Li designed and supervised this study, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30571907; the grant from the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai, No. 05QMH1409.

Ethical approval: This study received permission from the

Animal Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital, China.

[1] Bender MB, Fulton JF. Functional recovery in ocular muscles of a chimpanzee after section of oculomotor nerve. J Neurophysiol. 1938;1:144-150.

[2] Pallini R, Fernandez E, Lauretti L, et al. Experimental repair of the oculomotor nerve: the anatomical paradigms of functional regeneration. J Neurosurg. 1992;77(5):768-777.

[3] Fernandez E, Pallini R, Gangitano C, et al. The third nerve transection and regeneration in rats with preliminary results on the sixth nerve transection and regeneration in guinea pigs. Neurol Res. 1988;10(4):221-224.

[4] Li S, Pan Q, Liu N, et al. Neurotization of oculomotor, trochlear and abducent nerves in skull base surgery. Chin Med J (Engl). 2003;116(3):410-413.

[5] Fernandez E, Pallini R, Lauretti L, et al. Motonuclear changes after cranial nerve injury and regeneration. Arch Ital Biol. 1997; 135(4):343-351.

[6] Fernandez E, Pallini R, Marchese E, et al. Reconstruction of peripheral nerves: the phenomenon of bilateral reinnervation of muscles originally innervated by unilateral motoneurons. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(3):364-369.

[7] Magavi SS, Leavitt BR, Macklis JD. Induction of neurogenesis in the neocortex of adult mice. Nature. 2000;405(6789):951-955.

[8] Fernandez E, Pallini R, Sbriccoli A. Changes in the central representation of the extraocular muscles in the rat oculomotor nucleus after section and repair of the third cranial nerve. Neurol Res. 1985;7(4):199-201.

[9] Barmack NH. A comparison of the horizontal and vertical vestibulo-ocular reflexes of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1981;314:547-564.

[10] Akazawa C, Nakamura Y, Sango K, et al. Distribution of the galectin-1 mRNA in the rat nervous system: its transient upregulation in rat facial motor neurons after facial nerve axotomy. Neuroscience. 2004;125(1):171-178.

[11] Aldskogius H, Thomander L. Selective reinnervation of somatotopically appropriate muscles after facial nerve transection and regeneration in the neonatal rat. Brain Res. 1986;375(1):126-134.

[12] Ohlsson M, Mattsson P, Svensson M. A temporal study of axonal degeneration and glial scar formation following a standardized crush injury of the optic nerve in the adult rat. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22(1):1-10.

[13] Angelov DN, Skouras E, Guntinas-Lichius O, et al. Contralateral trigeminal nerve lesion reduces polyneuronal muscle innervation after facial nerve repair in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(4):1369-1378.

[14] Horie H, Inagaki Y, Sohma Y, et al. Galectin-1 regulates initial axonal growth in peripheral nerves after axotomy. J Neurosci. 1999;19(22):9964-9974.

[15] Eberhardt KA, Irintchev A, Al-Majed AA, et al. BDNF/TrkB signaling regulates HNK-1 carbohydrate expression in regenerating motor nerves and promotes functional recovery after peripheral nerve repair. Exp Neurol. 2006;198(2):500-510.

[16] Gorshkov RP, Ninel' VG, Dzhumagishiyev DK, et al. Experimental validation of direct long electrostimulation after neurotransplantation of the peripheral nerves. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2007;143(4):490-492.

[17] Tighilet B, Brezun JM, Sylvie GD, et al. New neurons in the vestibular nuclei complex after unilateral vestibular neurectomy in the adult cat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(1):47-58.

[18] Taupin P. BrdU immunohistochemistry for studying adult neurogenesis: paradigms, pitfalls, limitations, and validation. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53(1):198-214.

[19] Gordon T, Sulaiman O, Boyd JG. Experimental strategies to promote functional recovery after peripheral nerve injuries. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2003;8(4):236-250.

[20] The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2006-09-30.

[21] Belluzzi O, Benedusi M, Ackman J, et al. Electrophysiological differentiation of new neurons in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2003;23(32):10411-10418.

[22] Al-Majed AA, Neumann CM, Brushart TM, et al. Brief electrical stimulation promotes the speed and accuracy of motor axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2000;20(7):2602-2608.

[23] Fernandez E, Pallini R, Gangitano C, et al. Oculomotor nerve regeneration in rats. Functional, histological, and neuroanatomical studies. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(3):428-437.

[24] Atasever A, Durgun B, Celik HH, et al. Somatotopic organization of the axons innervating the superior rectus muscle in the oculomotor nerve of the rat. Acta Anat (Basel). 1993;146(4):251-254.

[25] Al-Majed AA, Brushart TM, Gordon T. Electrical stimulation accelerates and increases expression of BDNF and trkB mRNA in regenerating rat femoral motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000; 12(12):4381-4390.

Cite this article as:Neural Regen Res. 2011;6(26):2032-2036.

Wenchuan Zhang☆, Doctor, Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200092, China

Shiting Li, Doctor, Professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200092, China; Xinyuan Li, Doctor, Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong

University, Shanghai 200092, China

lsting66@163.com; Leexinyuan@hotmail.com

Supported by: the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30571907*; the Grant from the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai, No. 05QMH1409*

2011-04-15

2011-06-24

(N20110111007/WLM)

Zhang WC, Visocchi M, Fernandez E, Wang XH, Li XY, Li ST. Regenerating nerve fiber innervation of extraocular muscles and motor functional changes following oculomotor nerve injuries at different sites. Neural Regen Res.

2011;6(26):2032-2036.

www.crter.cn

www.nrronline.org

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374. 2011.26.006

We thank Dr. Guoshun Shen Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Xinhua Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University for his help with electrophysiological examinations.

(Edited by Guo GQ, Zhang L/Su LL/Song LP)