A Study on Relationship between De-Ozawa Campaign and Factional Regrouping of DPJ

Chen Gang

A Study on Relationship between De-Ozawa Campaign and Factional Regrouping of DPJ

Chen Gang

The de-Ozawa campaign refers to strong criticism of “money politics” of Ichiro Ozawa in the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) initiated by Naoto Kan, by relying on the non-mainstream Maehara and Noda factions during the Hatoyama cabinet period, taking advantage of Hatoyama’s resignation and making use of Ozawa’s political funding scandal. Kan intended to marginalize the biggest Ozawa faction in the party and achieve the“integration of power structure” in the DPJ by means of eliminating the political influence of Ozawa. This is not only the collective reaction to “Ozawa allergy” which has remained in the party for a long time, but also the natural result of the demand of the non-mainstream factions in the party for adjustment of power structure. The de-Ozawa campaign, however, has led to fission in the party which has not only made the functioning of the DPJ government more difficult, but also accelerated the regrouping of political forces within the party.

I. The De-Ozawa Campaign and “Reversal of the Ruling and the Opposition” of DPJ Factions

The factions of the Japanese political parties can be categorizedinto “mainstream” or “non-mainstream” factions in accordance with their status. In general, the faction from which the president of the party is originated and those close to it are called“mainstream factions” whereas factions keeping distance from the mainstream factions are named “non-mainstream” or “antimainstream” ones. For a new cabinet, posts of ministers, vice ministers, Diet members and posts in the party are mostly allocated in favor of members of the mainstream factions. On the contrary, the non-mainstream or anti-mainstream factions are relatively “given the cold shoulder” and play a supervisory and restraining role in the party just like opposition parties. The de-Ozawa campaign refers to strong criticism of “money politics” of Ichiro Ozawa in the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) initiated by Naoto Kan, by relying on the non-mainstream Maehara and Noda factions during the Hatoyama cabinet period, taking advantage of Hatoyama’s resignation and making use of Ozawa’s political funding scandal in an effort to sideline the biggest Ozawa faction in the party through eliminating his political influence and realize the“unification of the power structure” in the DPJ.

Due to the breakup of the coalition government for the relocation of the Futenma Air Base of the U.S. military forces and the political funding scandal, the Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama resigned on June 2, 2010. In his resignation statement, Hatoyama highlighted the huge negative impact of personal political funding on the promised “clean politics” of the DPJ. His resignation evoked a wave of criticism in the DPJ against the personal “politics and money” problems of Hatoyama and Ichiro Ozawa—leader of the biggest DPJ faction. On the afternoon of June 3, Naoto Kan, who was ready to campaign in the election of a new party president, solicited the support of Katsuya Okada, minister of foreign affairs, Seiji Maehara, minister of land, infrastructure, transport and tourism, and Yoshihiko Noda, vice-minister of finance. Regarding the political funding scandal of Ozawa, Okada indicated that as long as Naoto Kan committed himself to “eliminating dual power structure” and “creating a clean DPJ”, he would support the latter’s effort to seek election for party president. Seiji Maehara noted that on the issue of politics and money, the DPJ should make a new start. Yoshihiko Noda criticized Ozawa more directly as “an influential man who exerts his influence in places others do not see”. Naoto Kan’s commitment to eliminating “politics and money” problem won the support of non-mainstream Maehara and Noda factions in the party. On this basis, a de-Ozawa wave rose in the DPJ which reflected the mainstream opinion of DPJ in pursuit of “clean politics” and the demand of the non-mainstream factions of DPJ for adjusting power structure. The essence of the de-Ozawa campaign is that the anti-Ozawa factions, making use of the “politics and money” problem as the focal point in the election, relying on the mainstream opinion in the party, exercised moral pressure upon and struck at the Ozawa forces, to eliminate the dual structure of the party and shake off the effect of the“superiority of the majority” of the Ozawa faction on other political forces.

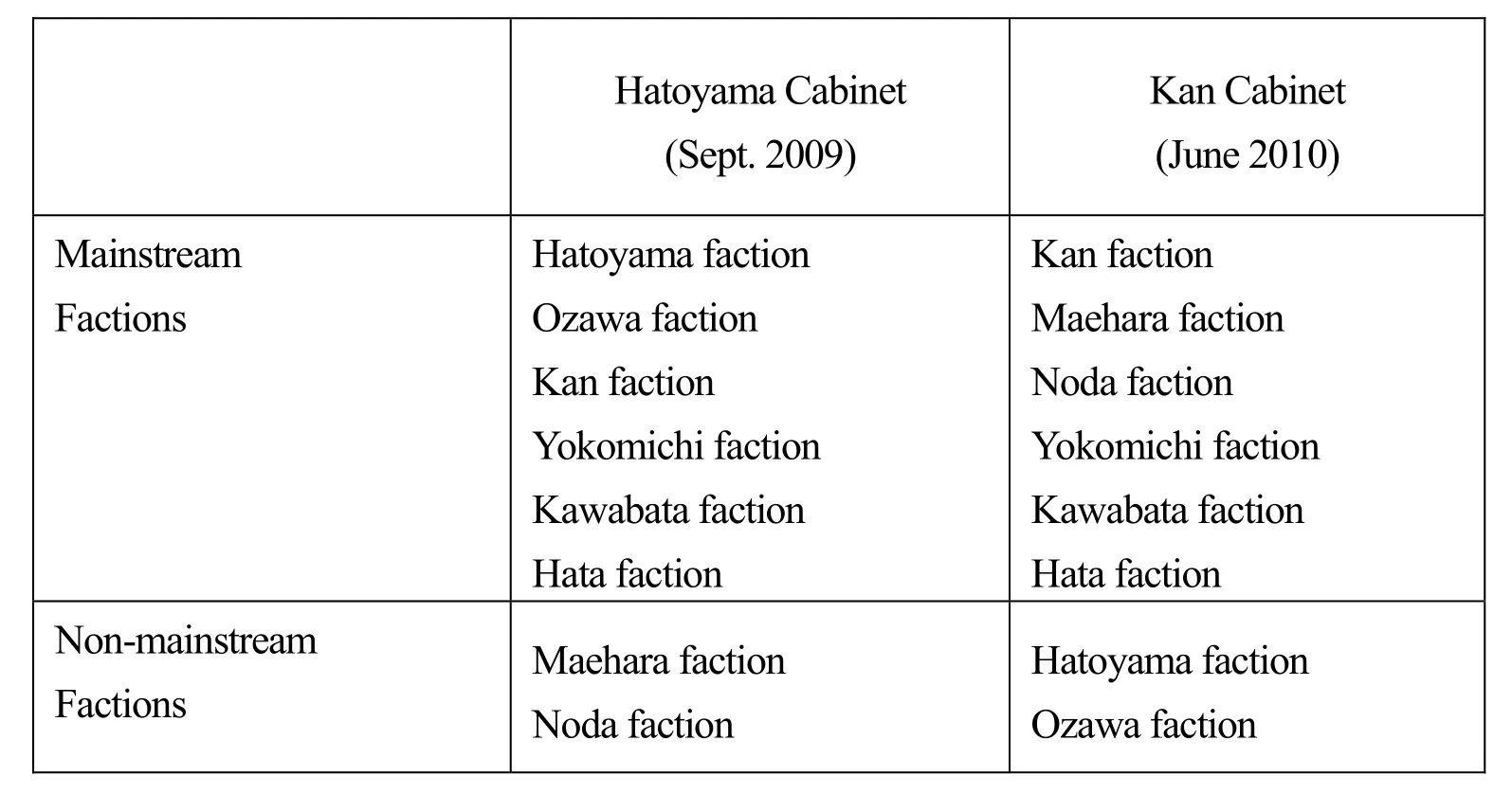

Pushed by the de-Ozawa wave, in particular after the presidential election of the DPJ in September 2010, there appeared among the DPJ factions the shift of position which was similar to“a regime change”. The Maehara and Noda factions gradually became the core of the mainstream factions of DPJ. Correspondingly, the Ozawa and Hatoyama factions were reduced to “non-mainstream” even “anti-mainstream” factions. Such a“reversal of the ruling and the opposition” highlighted the growth and decline of the factions in an era of “regime change”. The biggest drawback of the de-Ozawa campaign, however, was to put the biggest faction of DPJ—the Ozawa faction in the position of a non-mainstream faction, which shook the foundation of the regime and at the same time brought about inestimable risks for the smooth functioning of the DPJ in the Diet. The factional regrouping and reorganization of power triggered by the de-Ozawa campaign has become a major inherent reason for the instability of the DPJ regime.

Table 1.Status Changes of the DPJ Factions Caused by De-Ozawa Campaign

II. The Origins of the De-Ozawa Trend of Thought

The de-Ozawa trend of thought in the DPJ is deep-rooted. Ozawa’s personal experience as a “saboteur” and the overwhelming “quantitative superiority” of the Ozawa faction in the DPJ have largely contributed to the long-standing “Ozawa allergy”in the party. The political funding scandal of Ozawa turned out to be the fuse of the de-Ozawa wave in the DPJ.

First, the personal experience of Ichiro Ozawa.Ozawa, as one of “the seven warriors” of Takeshita faction—the biggest faction in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), was appointed deputy chief cabinet secretary after the Takeshita cabinet was set up. During the Toshiki Kaifu cabinet, he became secretary general of the LDP, the youngest secretary general in the history of the party. In the 1990 presidential election of the LDP, Ozawa, as secretary general, was accused of being insolent by the public opinion for calling Kiichi Miyazawa and other party veterans to his office for an interview. Later, divergence in political views between Ozawa and Keizo Obuchi led to the breakup of the Takeshita faction, the biggest faction in the LDP. Then, Ozawa’s rebellion facilitated the adoption of the no-confidence motion of the opposition parties against the Miyazawa cabinet, leading directly to the downfall of the Miyazawa cabinet and the breaking up of the“1955 system” of the LDP. After leaving the LDP, Ozawa founded the Japan Renewal Party and in 1994 he established the New Frontier Party. After the dissolution of the New Frontier Party at the end of 1997, Ozawa established the Liberal Party. In early 1999, the Liberal Party joined the Keizo Obuchi government, forming a regime of “union of the LDP and the Liberal Party”. In April 2000, the Liberal Party left the LDP government. In 2003, through the mediation of Naoto Kan, the Liberal Party led by Ozawa formally merged into the Democratic Party of Japan. Ozawa was called a “saboteur” because of his behavior of “undermining and establishing parties” on several occasions. The division of the LDP and later the split and dissolution of the New Frontier Party both facilitated by Ozawa became the eloquent evidence of his“arbitrariness and politics of favoritism” in the evaluation of him by the public. In particular, since the Mirihiro Hosokawa government in 1993, many of his colleagues harbored grudges against his style. The “Ozawa allergy” was more obvious among the veteran Diet members during the LDP regimes compared with the young Diet members of the ruling DPJ. For instance, in 1994 during the Tsutomu Hata government, Ozawa once excluded the Japan Socialist Party when organizing a unified faction, arousing the displeasure of the Japan Socialist Party. This somewhat explains the historical conflict between Ozawa and the anti-Ozawa Yokomichi faction in the DPJ, whose backbones are the former Japan Socialist Party lawmakers.

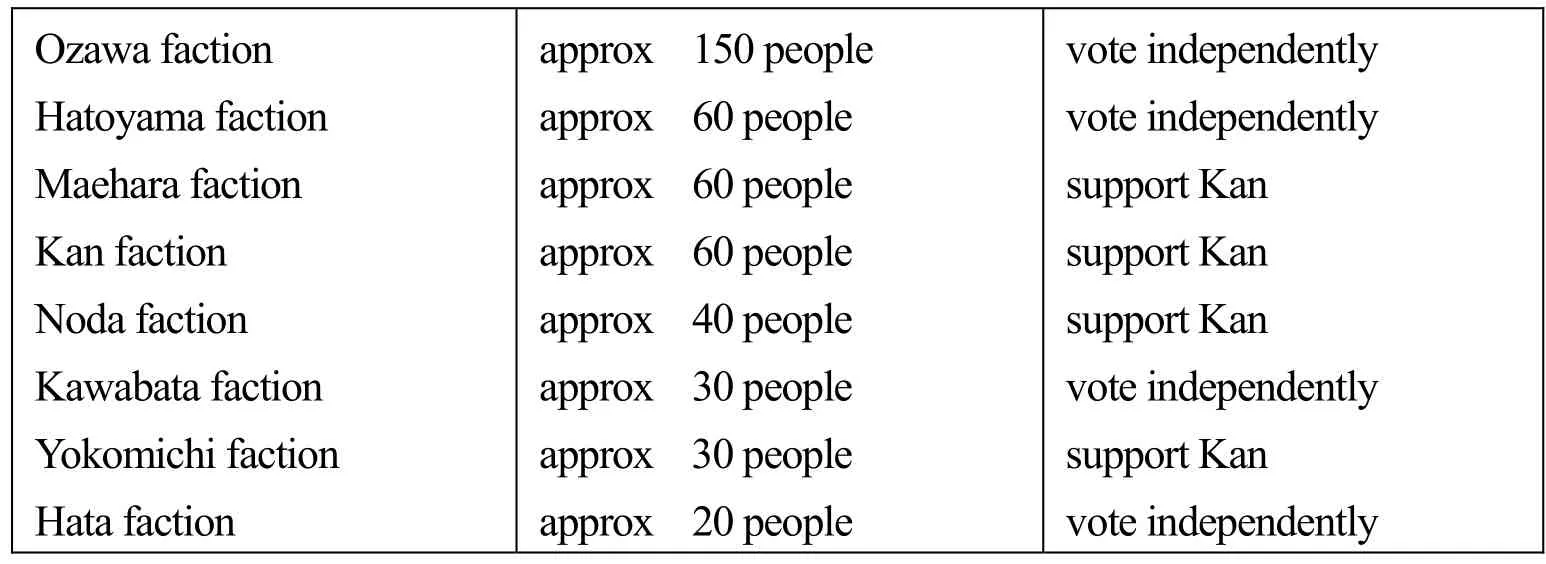

Second, the force of the Ozawa faction.The factional force mainly counts on the number of members of a given faction in the House of Representatives and House of Councilors of the Diet. The factional force is adjusted in accordance with the election result of the upper and lower houses. Many new Diet members emerged in the 2007 upper house election when Ozawa was president of the party and in the 2009 lower house election where the campaign had been actually under Ozawa’s guidance. This enabled the Ozawa faction to expand quickly to become the biggest faction in the DPJ. Due to the great fluidity of lawmakers between different factions in the DPJ, the major media usually give round numbers of lawmakers in factions on specific dates in their reporting. According to the report of Asahi Shimbun on May 16, 2009, during the leadership election of the DPJ in May 2009, the Ozawa faction had about 50 members, the Hatoyama faction about 30, the Kan faction about 20, the Noda faction about 20, the Maehara faction about 20, the former Japan Socialist Party members (Yokomichi faction) about 20, former Democratic Socialist Party members (Kawabata faction) about 25. In the House of Representatives election at the end of August 2010, the DPJ won a landslide victory over the LDP—the evergreen on the Japanese political stage. Of the 480 seats in the House of Representatives, the DPJ won 308 seats. The number of DPJ lawmakers went up by a big margin after this election and, thanks to Ozawa’s choices and guidance, quite a lot of young party members were elected. The election of party members who were close to Ozawa made the structure of factions in the DPJ further uni-polarized. The Asahi Shimbun reported on September 3, 2009 that the composition of the factions in the DPJ after the election was: the Ozawa faction about 150 lawmakers, the Hatoyama faction about 45, the Kan faction about 30, the former Japan Socialist Party (Yokomichi faction) about 30, the former Democratic Socialist Party (Kawabata faction) about 30, the Hata faction about 20, the Maehara faction about 30 and the Noda faction about 35. After the lower house election, the force of the Ozawa faction precipitously bulged and the imbalance of force between the factions in the party was becoming prominent. To a great extent, the setting up of the Hatoyama cabinet was seen as tinted with the hue of Ozawa. In the DPJ, Kozo Watanabe held Hatoyama up to ridicule for “being led by Ozawa and lacking his own judgment”. Behind the worry about the “dual political structure” was the collective reaction within the DPJ to the invisible pressure exerted by the “quantitative superiority” of the Ozawa faction.

Finally, the “politics and money” issue became the fuse of the de-Ozawa campaign.Firstly, the DPJ, taking “reform” as its slogan and “regime change” as its objective, criticized money politics, closed-chamber politics and the “iron triangle” of politicians, government officials and industrial circles that had existed for a long period of time during the LDP regimes. The DPJ stood for breaking up the current official system, standardizing the political funding of enterprises to “restore the trust of the nationals in politics and make public the truth of political funding” and build up a “clean” Democratic Party of Japan. Many politicians in the DPJ such as Katsuya Okada were active advocates for the politicians keeping away from money and the standardization of the funding of enterprises. No doubt, the political funding scandals in the DPJ have hurt the clean image of the party. Secondly, the political funding scandals became the latent danger for the DPJ’ s loss in the House of Councilors election in 2010. The political funding scandals of Ichiro Ozawa and Yukio Hatoyama made the support rate of the Hatoyama government tumble down sharply. From early 2010, the DPJ began to worry that the political funding problem would affect the upper house election in July 2010. In an interview with Asahi Television on February 28, 2010, Seiji Maehara, minister of land, infrastructure, transport and tourism, stated that “how to win the House of Councilors election is an important matter requiring careful consideration”, urging Ozawa indirectly to admit his political funding and resign. On March 18, 2010, when Yukio Ubukata, deputy secretary general of the DPJ, was interviewed by Sankei Shimbun, he noted in direct criticism of Ozawa’s political funding that “it is essential that Secretary General Ozawa explains once more to the nationals his own political funding problem. If he fails to receive their under-standing, his resignation will be imperative”. Finally, Hatoyama’s resignation confession offered a good opportunity for the public opinion of the DPJ. On June 2, 2010, Hatoyama announced resignation. Among others, one of the reasons for resignation was his political funding problem. So an upsurge of moral criticism of Ozawa’s “politics and money” problem appeared rapidly within the DPJ. Seiji Maehara and Yoshihiko Noda, who remain alienated from Ozawa, criticized in a high profile Ozawa’s political funding problem and the “dual political structure” of the party. By virtue of his moral advantage, Naoto Kan swiftly realized the regrouping of mainstream factions and formed a “ring of encirclement of Ozawa”in the party.

III. The De-Ozawa Process and Factional Regrouping

The de-Ozawa campaign, initiated after Naoto Kan set up his cabinet in June 2010, is divided into two main phases. The development and evolvement of the two periods not only tremendously disrupted the regrouping of the ruling and opposition political factions in the DPJ, but also had strong impacts on the traditional factional structure of the party. The range of subversions and impacts affected the stability of the Naoto Kan regime, and had tremendous bearing on the internal and foreign affairs of the DPJ government. They have become an inherent factor in the policy reversals and turbulences of the government.

Prior to Hatoyama’s resignation, the hidden waves seeking the elimination of Ozawa’s influence began to roll. Because of the continuous fall of the approval rate of the Hatoyama cabinet, before the House of Councilors election in July 2010, comments about election defeat and the decline of the Hatoyama government gradually surfaced in the DPJ and preparations and planning for the post-Hatoyama era were on-going silently. “The seven warriors of the DPJ” including Yoshihiko Noda who held aloof from Ozawa suspended the criticism of Ozawa before the House of Councilors election, to a large extent, they intended to make use of the election for their further attacks on Ozawa. “In case of failure in the House of Councilors election, Ozawa’s responsibilities will be ascertained. Anyway, his political life will last only two to three years.” But owing to the early resignation of Hatoyama and the need of Naoto Kan to solicit the support of the non-mainstream factions in the party, the prelude had already begun for the de-Ozawa campaign in the party before the upper house election.

The first phase of the de-Ozawa process was from June 2010 when Hatoyama resigned to September 2010 before the party leader election of the DPJ which was manifested in three aspects:

1. Forming a “ring of encirclement of Ozawa” in the DPJ.On the basis of seeking support from Katsuya Okada, minister of foreign affairs who is well-known for seeking “clean politics” in the party, Seiji Maehara and Yoshihiko Noda, leaders of nonmainstream factions, Naoto Kan rapidly formed a ring of encirclement of Ozawa within the party aimed at eliminating the“politics and money” problems. Among the eight major factions in the party, the Kan, Maehara and Noda factions expressed explicitly and separately support for Naoto Kan. Under the circumstances where Naoto Kan successfully unified the non-mainstream factions in the party, the intermediate forces such as the Hata, Yokomichi and Kawabata factions, pushed“morally” by the de-Ozawa campaign, began to disintegrate. Differences stemming from personal sentiments and political morality became more evident in the above three factions. In the party leadership election, the intermediate factions evolved into the debate between the Ozawa and anti-Ozawa blocs. Finally, the Yokomichi faction explicitly supported Naoto Kan and the Kawabata, Ozawa and Hata factions gave up voting because of their internal differences. On the evening of June 2, Yukio Hatoyama noted to the journalists that he did not have the intention to support anyone identified beforehand. With this standpoint, the members of Hatoyama faction tended to favor voting independently. With the solidarity of the Kan, Maehara and Noda factions, the new mainstream factions had nearly 160 people—almost the same as the Ozawa faction. The new mainstream factions, as well as the diversion of the independent votes constituted the supporting system of the Kan cabinet to some extent.

Table 2 Ring of Encirclement of Ozawa Formed during DPJ Leadership Election

2. In matters related to distribution of posts.In matters related to the distribution of posts, the Naoto Kan government that was formed in June 2010 adopted the personnel distribution structure that stressed “de-Ozawa hue” in party affairs and emphasized balance among the factions in government composition. Such a dual distribution structure highlighted the contradiction between the two major options of meeting the upper house election as a united party and the elimination as much as possible of the adverse impact of the political funding problem on the DPJ.

In party affairs, there was the newly-formed “Kan-Sengoku-Edano” system. While appointing Yoshito Sengoku, who kept his distance from Ozawa, to the important post of chief cabinet secretary, Yukio Edano, an anti-Ozawa vanguard, was given the important post of secretary general of the DPJ, which was mainly aimed at showing the posture of getting rid of Ozawa’s influence. Moreover, the Policy Research Committee, once abandoned by Ozawa, was restored and Satoshi Arai of the Kan faction was concurrently chairman of the committee. Prior to that, Satoshi Arai, as representative of the Kan faction, became minister of state for national policy in the cabinet. The fact that chairman of the Policy Research Committee took up a cabinet post meant not only to boost the vitality of the DPJ, more importantly, it was to make use of concurrency of posts in the party and cabinet to change the dual structure which had existed in the Hatoyama period to build up the so-called “cabinet of integrated policy-making”.

Table 3 Distribution of Members of Factions in Democratic Party Cabinets

In the appointment of cabinet officials, 12 of the Hatoyama cabinet members were retained. It may be seen in Table 3 that among the Kan cabinet members there were two from the Kan faction, two from the Maehara faction, two from the Noda faction, two from the Ozawa faction, two from Kawabata faction, two from the Hata faction, one from the Yokomichi faction, one from the Hatoyama faction and three without faction affiliation in the party. The new cabinet members included Yoshihiko Noda, Renho, both from Kasei-kai of the Noda faction, Koichiro Genba, a DPJ member without faction affiliation, Satoshi Arai, from Kuni no katachi kenkyukai (State Form Research Committee) of the Kan faction. The above four stood aloof from Ichiro Ozawa. Although the cabinet posts were relatively evenly distributed among the factions, it was not the case in the distribution of the vice ministers, assistant ministers: both deputy chief cabinet secretaries were from the Maehara faction and three out of the four assistants to the prime minister were from the Kan faction. Of the 21 vice minister posts, the Kan, Maehara and Noda factions occupied 10; of the 26 assistant ministers, 15 from the three factions. It may be seen that in cabinet personnel matters, while inheriting the basis of balance of force among the factions, Naoto Kan focused on enhancing the position of the mainstream Maehara and Noda factions.

3. Amending election program.First, the slogan advanced by the DPJ in the 2009 House of Representatives election was“Putting People’s Lives First”. The election program set forth various solutions on issues of people’s livelihood, for example, distributing children subsidies, rebuilding the social security system, no consumption tax hike, etc. Japan is quite restrained in fiscal revenue due to its big fiscal deficit and government debt. Therefore, after the Kan cabinet took office, the DPJ executives revised the distribution of children subsidies and stood for raising consumption tax rate to 10 %. This directly negated the election program jointly formulated under the guidance of Ozawa in 2009. The Kan cabinet provoked the controversy on consumption tax prior to the upper house election was believed to hope to shape“ultra-party” controversy and consensus. The Kan government called on “Japan to get rid of huge fiscal deficit, no matter the ruling DPJ or the opposition LDP must consider raising the current consumption tax rate by 5%”. Second, exploring to seek ultra-party consensus to eliminate the quantitative pressure of the Ozawa faction and “dual political structure” in the party. Due to the concern over Japan’s huge fiscal deficit after the eruption of the European debt crisis and the restraint on implementing subsidy policy out of the insufficient financial resources of the DPJ regime, Yoshihiko Noda who held different views from those of Ozawa was appointed as the minister of finance after the Kan cabinet was set up. After taking office as minister of finance, Noda had adequate reason and jurisdiction to amend the election program dominated by Ozawa. With the major goals of controlling government expenditure and achieving fiscal reorganization, raising consumption tax rate and supplementing government financial resources were the outstanding features of Noda finance which shook off the restraint of the current policies of the Ozawa election program and constituted an important measure in the de-Ozawa campaign of the DPJ.

The second phase of the de-Ozawa campaign was mainly around the leadership election of the DPJ. In this phase, as Ozawa participated formally in the leadership election of the DPJ, the divergence between Ozawa and Naoto Kan came into the open in an all-round manner. The leadership election of the party prompted the mainstream factions to step up the high-profile criticism of the “politics and money” problems and drastically tilted the public opinion within the party, making Naoto Kan take more resolute steps in the de-Ozawa campaign. This was specifically reflected in following two aspects:

1. Thoroughly remove the Ozawa force in cabinet and party affairs.As the leadership election of the party in September caused the division of the party, Naoto Kan who defeated Ichiro Ozawa in the election and continued to be prime minister took drastic steps in the de-Ozawa campaign and began an all-round reorganization in party and cabinet affairs. He chose Katsuya Okada without faction affiliation to be secretary general of the party to shape the ultra-faction political image of the Kan government. Moreover, Okada is renowned for criticizing money politics of Ozawa and wins the support of the public opinion with a “clean” political image. The distribution of cabinet posts was: two from the Kan faction, two from the Maehara faction, two from the Noda faction, two from the Yokomichi faction, two from the Kawabata faction, two from the Hata faction, two from the Hatoyama faction, none from the Ozawa faction, two without faction affiliation and one commoner. While continuing to enhance the dominant position of the Kan, Maehara and Noda factions, Kan made vigorous efforts to win over the intermediate forces, for instance, appointing the commoner Yoshihiro Katayama as minister of state for regional revitalization and inviting Michihiko Kano of the Hata faction and Yoshiaki Tanaki of the Kawabata faction into the cabinet. After Keiko Chiba, candidate of the Yokomichi faction, failed in the House of Councilors election in July, the Kan government promptly asked Ryu Matsumoto and Tomiko Okazaki of the Yokomichi faction to join the cabinet to prop up the position of the flank of the mainstream in the Yokomichi faction. Meanwhile, Kan dismissed those close to Ozawa in the cabinet. For example, he replaced Kazuhiro Haraguchi, minister of state for regional revitalization, who had explicitly expressed support for Ozawa in the election. Kan achieved a new mainstream regime without Ozawa force through continued consolidation in party affairs and the drastic reshuffle of the cabinet.

2. Call for Ozawa to appear before the Political Ethics Hearing Committee of the Diet.The Kan regime failed in the House of Councilors election and lost points in Japan-China and Japan-Russia relations. Under huge pressure from the House of Councilors, the Kan regime met with increasing difficulties in the functioning of the Diet and saw its approval rate continually go down and, under the pressure of the opposition parties, had to replace Minoru Yanagida, minister of justice for “improper remarks”. The Kan cabinet hoped to win back the confidence of the people on the “politics and money” issue, therefore, it continued to lay stress on the issue and call for Ozawa to appear before the Political Ethics Hearing Committee. This indicated that under the pressure of the opposition parties, the Kan government hoped to call for Ozawa to appear before the Political Ethics Hearing Committee in exchange for support of the opposition parties in the operations of the Diet such as coordination in the supplementary budget bill and 2011 budget bill. On the other hand, it expected to thoroughly eliminate the influence of Ozawa in the DPJ by the prosecution of Ozawa in order to promote a unitary political structure dominated by Naoto Kan. Calling for Ozawa to appear before the Political Ethics Hearing Committee aroused a strong reaction of the Ozawa faction, constituting a huge hidden danger of disintegration of the DPJ. For this reason, the Kan government stepped up efforts to win over the opposition parties. The attempt of the Kan government to strive for the establishment of a coalition government with the Japan Socialist Democratic Party and the “Get It Up, Japan” Party in December 2010 was seen to a certain degree as an effort to mitigate the risk of division in the party caused by the de-Ozawa campaign through the regrouping of political forces.

IV. The Impact of De-Ozawa Campaign on the Structure of DPJ Factions

With the progress of the de-Ozawa campaign, under the Naoto Kan government “a reversal of the ruling and the opposition” in the DPJ occurred between the mainstream and non-mainstream factions, which not only brought about a strong shock on the intermediate factions and prompted their further disintegration, but also affected the loose faction structure of the party, bringing the concurrent faction affiliations in the party to the focus of attention.

First, under the impact of the de-Ozawa tide, the intermediate Yokomichi, Kawabata and Hata factions began to sway and their internal divergences are further intensified. The intermediate factions had a strong sense of banding together, but they are inadequate in integration. For instance, in party leadership elections in June and September 2010, the Kawabata faction tended to elect its own independent candidate. However, the faction did not have a strong core figure. Due to the internal differences which could not be dissolved, the faction opted for independent voting in the end. In the DPJ, under the impact of“dual morality”—the mainstream factions’ claim to build up a clean DPJ and the non-mainstream factions’ claim that the DPJ hero in the seizure of regime should not be abandoned, the anti-Ozawa and pro-Ozawa forces of the intermediate factions began further differentiating, which directly weakened their cohesive force.

Second, under the shock of the de-Ozawa campaign, the loose organization of traditional factions stepped up the internal interflow of people and reorganization. Different from the LDP, the organization of the DPJ is relatively loose and lawmakers may be affiliated to different political factions in the party. The DPJ faction leaders have difficulty in making the final decision on the orientation of the factions in the votes so that in the presidential election of the party, the party members freely decide upon their votes in accordance with the general social opinion and their impressions of policies and individual candidates. This indicates that in the DPJ, intermediate forces are numerous. Akihiro Ohata, current minister of land, infrastructure, transport and tourism, wrote in his diary that “in the DPJ which is trying to realize new politics, one may feel restrained in action when he belongs to any faction, and all this will make the party return to the previous state of politics. I do not belong to any faction, nor do I join any factional activity. From the outset, a politician should be an independent voter, make his judgment in accordance with policies, knowledge and actions and refrain from being restrained by the views of the factions.” To a certain extent, this reflects the political attitude of the middle-of-the-road lawmakers. The existence of hidden intermediate forces enhanced the difficulty of the major factions in judging their own strength before the leadership election of the party. On the basis of the judgment of the “wavering” attitude of the intermediate forces, the DPJ executives even thought that “if Ozawa left the party, only 20 to 30 legislators would follow him”.

The appearance of the above feature is mainly determined by the features of the factions in the DPJ. First, in the development of faction politics in the DPJ, there was no strict restraint in political belief. The initial objective of the factions was only to facilitate election or boost the right to speak in the party. Without the support of political faith, organization is loose and is sustained by various personal relations between individuals. Therefore, the interflow of members between factions was relatively frequent and some Diet members joined two or more factions at the same time. Moreover, the Diet members without faction affiliation in the party accounted for a large proportion, which has blurred the distinction of factions. Second, the liberal trend of thought formed in the DPJ had a profound effect on the functioning of factions. For example, Yukio Hatoyama advocated to the effect that “each person, with the unlimitedly diversified character, should be an existence that cannot be substituted, and therefore be entitled to decide upon his own destiny”, “we attach importance to ‘individual independence’ ”. Such endorsement of personal identity and independence constitutes an important reason for the lack of cohesive force in political factions. Finally, owing to the introduction of small constituencies for the first time in 1996, factions can hardly get involved in putting forward candidates so the role of party factions was weakened. Under these circumstances where the DPJ was founded, from the outset the faction leaders’ dominance was sapped. Inadequate dominance of faction leaders indicated their poor performance in easing internal disputes.

However, there are aliens in the factions of DPJ. In recent years, Young Turks are increasing progressively in the DPJ, for example, the majority of members of the Maehara and Noda factions are young Diet members who hail from the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management and are often referred to the“circles of Matsushita Institute” ironically. In particular, all the members of Kasei-kai of the Noda faction and its predecessor Shishino-kai came from the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management and had a very conservative hue. Even members of Ryoun-kai within the Maehara faction who had close ties with Kasei-kai accused it of a distinct exclusive feature. But such outstanding tint became an asset for the expansion of Kasei-kai. In the de-Ozawa wave pushed by Naoto Kan, the distinct character of the Noda faction enabled it to establish the core position among the mainstream factions of the Kan government.

V. Analysis of the Impact of De-Ozawa Campaign on the Ozawa Faction

The Ozawa faction which has a quantitative advantage in the DPJ is generally divided into four parts: Isshin-kai (Wholehearted way) as its nucleus, the Isshin-kai Club with new lower-house members as the backbone, the Ozawa faction in the House of Councilors and the old Liberal Party faction. The reason why these parts are not unified is the concern that the overwhelming superiority of the “Ozawa legion” may arouse suspicion and panic in the party when they are unified. Although the Ozawa faction boasts “ironclad unity”, the majority of the members are youngsters without the prop by strong key figures. Under the impact of the de-Ozawa campaign, the internal cohesion of the Ozawa faction began to weaken.

Firstly, contradictions and conflicts erupted in the faction. During the leadership election of the party in June 2010, at the outset the Isshin-kai Club once decided to vote as one group, but Isshin-kai made the decision to vote independently, so the Isshin-kai Club decided to vote independently in the end. After Ozawa was defeated in the leadership election of the party in September 2010, all parts tried to shirk the responsibility for the election defeat within the Ozawa faction and fire was concentrated on Kazumasa Okajima, director of Isshin-kai, who had prompted Ozawa to challenge Naoto Kan. Secondly, the de-Ozawa campaign sidelined this biggest faction in the DPJ, for instance, confidants of Ozawa like Kenji Yamaoka, chairman, Kenko Matsuki, vice chairman, of the Diet Affairs Committee, and Ozawa’s former secretary Takeshi Hidaka were all dismissed by the new enforcement division of the DPJ. The Ozawa faction lost all the posts in the party in charge of financial matters such as post for Diet policy and post for election policy, which directly impacted the cohesion and political funding of the faction. Finally, owing to the focusing of the Kan government on the issue of“politics and money”, in the Ozawa faction many pessimistic views on future emerged. For instance, to avert association with the problem of “politics and money” of Ozawa, the number of participants at the routine meetings of Isshin-kai declined. Isshin-kai boasted 45 members, but only more than 20 showed up at its November 9 routine meeting.

Even so, due to the strong “Maehara and Noda” hue of the Kan government and its loss of points in internal and foreign affairs, the “clean politics” of Naoto Kan with the de-Ozawa campaign as its initial goal began to be called in question within the party. In particular, calling for Ozawa to appear before the Political Ethics Hearing Committee was accused by some pro-Ozawa Diet members as “the DPJ’s abandoning of the greatest hero in seizing the regime” and “l(fā)ack of morality”. Given these circumstances, the Ozawa faction stepped up internal reorganization to strive for the support of the intermediate factions as much as possible to shake off the present dilemma.

First, it intensified the reorganization and consolidation of the faction. In view of the breakup of Isshin-kai, on November 25, 2010 the newly-elected Diet members supportive of Ozawa set up a new lawmaker organization Hokushin-kai with 43 initial members and Ozawa as the supreme adviser. Hokushinkai was formed through reorganizing the Isshin-kai Club comprising Diet members elected for the first time.

Second, “Hatoyama-Ozawa alliance” was formed. In the early stage of the de-Ozawa wave, Yukio Hatoyama once served as mediator between Kan and Ozawa in the hope that the Kan government would “treat amicably” Ozawa and achieve fraternity and unity in the party. However, the Kan government dominated by the former non-mainstream factions gradually gave less prominence to the “fraternity” and “East Asia Community”

conceptions advocated by Hatoyama and weakened the position of National Strategy Bureau set up by Hatoyama. This prompted Hatoyama to strengthen his faction’s position, support Ozawa, and enhance the efforts to win over and unify the intermediate factions. Before merging into the DPJ, Ozawa’s Liberal Party, Tatsuo Kawabata’s New Fraternity Party and Tsutomu Hata’s Good Governance Party had rather close connections because they were reorganized parties after the disintegration of the New Frontier Party. On December 22, 2010, Diet members of the Ozawa faction and Kansei Nakano and Keishu Tanaka, pro-Ozawa legislators of the Kawabata faction, set up the Diet Members’ Union for Oil Resources Policy Research. This was deemed as an important measure of the Ozawa faction to win over the Kawabata faction.

While boosting internal cohesion and enhancing the “sense of banding together”, the Ozawa faction could not avert its inherent defects which were highlighted in the following two aspects:

First, more than half of the members of the faction were young lawmakers and there were not strong successors like Noboru Takeshita of the then Tanaka faction of the LDP. Compared with the unity in policy and organization, the private relations with Ozawa were a more important factor in keeping the cohesion of the faction. Therefore, if Ozawa was prosecuted or left the DPJ, it would mean that the faction would lose its axis and cohesion, and that the faction would possibly disintegrate. And factional forces may gradually divert toward forceful pro-Ozawa lawmakers outside the Ozawa faction such as Shinji Tarutoko, former chairman of the Diet Affairs Committee, Banri Kaieda, minister of economy, trade and industry, and Kazuhiro Haraguchi, former minister for regional revitalization who supported Ozawa in past leadership election of the party.

A second, the Ozawa faction made a wrong attempt at keeping centripetal force of the organization. For example, Isshin-kai originally set the day of Thursday for its weekly routine meeting, but because of the overlapping of time with the regular meeting of the Hatoyama faction, after the leadership election of the party in September 2010, for the convenience of the members who were affiliated to different factions, Isshin-kai rescheduled the routine meeting to Monday evening. Later, due to poor attendance, the meeting was shifted to the daytime of Monday since November. In contrast, for the routine meeting of Ryoun-kai of the Maehara faction, the faction did not mind such overlapping in scheduling. Isshin-kai’s behavior was seen as a reflection of “weakness”. Meanwhile, this showed that the Ozawa faction did not recognize thoroughly the unfavorable impact of the Diet members’ multiple faction affiliations.

Chen Gang is Researcher at Zhejiang Academy of Social Sciences.

China International Studies2011年3期

China International Studies2011年3期

- China International Studies的其它文章

- The Current State of Chinese NGOs’ Participation in UN Activities

- Russia and the Afghanistan Issue

- Europe 2020 Strategy and Low Carbon Economy

- US Would Face a Dilemma Should It Interfere Militarily in the Diaoyu Islands Dispute

- North-South Interactions in the East Asian Regional Cooperation

- A Review of President Obama’s Environmental Diplomacy