Where is the path to recovery when psychiatric hospitalization becomes too difficult?

Bin XIE

· Forum ·

Where is the path to recovery when psychiatric hospitalization becomes too difficult?

Bin XIE

Forum: Forensic issues in involuntary hospitalization

The modern history of mental health services in China dates back to the founding of the fi rst psychiatric hospital in Guangzhou by the missionary physician John Kerr in 1898. By the time of liberation in 1949 China’s population was already 500 million but there were only 10 mental health institutions, 1 100 psychiatric beds and 50-60 psychiatrists in the country. Health services developed rapidly in the 1950s but by 1957 there were still only 70 psychiatric hospitals with 11 000 beds and less than 500 psychiatrists[1].

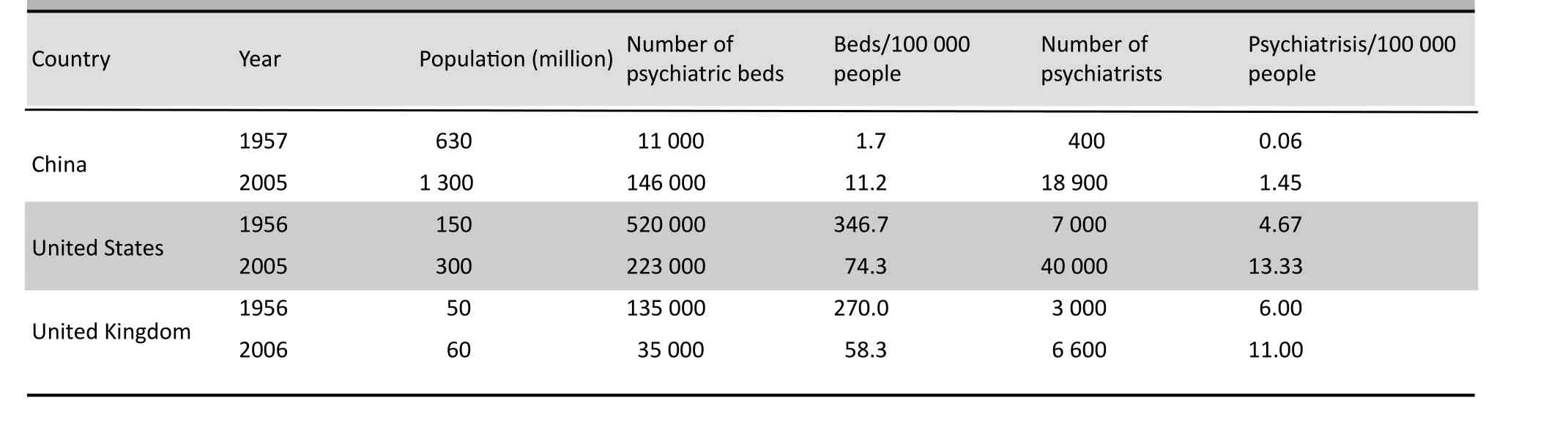

As shown in the table, the trajectory of the development of mental health services in Europe and the United States was quite different. After a century of increasing rates of chronic institutionalization of the mentally ill, by the mid-1950s the United States had more than 350 psychiatric hospitals with more than 500 000 beds for its population of 150 million and the United Kingdom had 130 psychiatric hospitals with 150 000 beds for its population of 50 million. Atier this peak there was a period of rapid deinstitutionalization in Western countries that accelerated in the 1960s. This was accompanied by a corresponding increase in community-based social service networks for mentally ill individuals and an expansion of the numbers and types of mental health providers. For example, by 2004 there were 110 000 psychiatric social workers in the United States, more than the combined number of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses. These changes made it possible to implement legislation that emphasized giving the patient as much autonomy as possible, providing treatment in the least restrictive setting feasible, and replacing involuntary hospitalization with compulsory outpatient or community-based treatment[2].

Despite increasing rates of hospitalization of the mentally ill in China over the last 50 years, by the mid-2000s the per capita number of institutions, beds and providers were still far below those in Western countries that had already undergone substantial downsizing as part of the deinstitutionalization process[1-5]. More importantly, lack of financial investment in community health services in China has meant that community mental health services are very limited or non-existent beyond a few large, economically developed municipalities. The development of such services has also been limited by the lack of psychiatric social workers, occupational therapists and clinical psychologists, important members of the multi-disciplinary teams that are needed to provide community-based services. A large-scale pilot project supported by central government aimed at addressing this lack of services started in 2004[6], but there is still a very long way to go.

Given the lack of community-based services hospitalization is the only viable option despite the heavy financial burden it places on patients and their families. Traditional Chinese cultural values emphasize the responsibility of families to care for ill family members; in the case of the mentally ill this heavy responsibility is magnified by the social stigmatization of mental illnesses, so families often avoid seeking professional care until the symptoms are so severe that they cannot be managed on an outpatient basis. A nationwide survey in 2002[7]reported that over 80% of all psychiatric hospitalizations in China are involuntary. However, less than one-quarter of these involuntary hospitalizations were because of ‘dangerous behaviors’; the others occurred because the family was unable to manage the patient at home.

Some municipalities in China have developed local legislation that addresses the legal issues related to involuntary admission of mentally ill patients. For example, the Shanghai Municipality Regulations on Mental Health implemented in 2002 established clear criteria and procedures for family members to represent the interests of the patient during the admission process, allowing mentally ill individuals tobe involuntarily admitied if the family and the treating psychiatrist considered this in the best interests of the patient. This put the long-standing practice of family supervision of hospitalization of the mentally ill into a clear legal framework. Over the nine years since implementing the regulations until the end of 2010 there have been an estimated 145 000 psychiatric admissions throughout Shanghai, but there have only been 11 formal legal complaints about this method of hospitalizing patients. This shows that legally formalizing the traditional practice of having family members coordinate the admissions of severely psychotic patients is feasible in China and can ef f ectively balance the needs of patients, families and the public.

The current drati version of China’s national mental health law[8](which, when passed, will supersede current local regulations) does not allow family members to supervise the involuntary admission of non-violent patients—admissions that currently constitute at least 60% of all psychiatric admissions in the country. As currently written the law severely restricts involuntary admissions to cases in which the patient is a clear danger to self or others and gives patients ample opportunity to challenge the psychiatric diagnosis and the decision to require an involuntary admission. Some legal experts are suggesting that the legal provisions need to be even more stringent, recommending that any involuntary admission require the approval of a judge following a court proceeding. As the law gets closer and closer to fi nal passage this part of the comprehensive legislation has stimulated heated debate.

Given the inadequate financial support for the provision of psychiatric services, the weak or nonexistent community service network and the severe shortage of mental health providers (particularly psychiatric social workers), this drastic restriction of involuntary admission by legal means will inevitably lead to a range of undesirable consequences. The family burden of caring for their mentally ill members will increase. There will be a greater risk of dangerous behavior by patients who lack supervision in the community. Psychiatric hospitals will only admit the most dangerous patients. The stigmatization and discrimination of both the mentally ill and psychiatric hospitals will get worse. And more legal proceedings (with their associated costs) will be needed to deal with litigation related to complaints about mentally ill individuals.

Developing clear legal safeguards that protect patients’ autonomy and reduce involuntary hospitalizations is the clear and unwavering goal of all those involved in providing mental health services. However, the current version of the national law places too great an emphasis on patient’s self-sufficiency; it gives the impression that prevention of inappropriate psychiatric hospitalization is the central purpose of the law. Introducing legislation focused on patient’s autonomy that does not take into consideration of traditional culture, the history of the provision of mental health services, or currently available community resources may not be in the best interests of those suffering from mental illnesses. In protecting patients’ independence beyond all other considerations we would be restricting their ability to exercise their other rights, including the right of health, education and work; and, thus, increasing the burden on both the family and society.

Is the new direction for service delivery previewed in this draft law going to be a blessing or a curse for patients in China?

Table 1. Mental health service resources in Western countries and China in the 1950s and 2000s

1. Xie B. Mental health care in China. Hong Kong Journal of Mental Health, 2011, 38(1): 4-9.

2. Xie Bin. Challenges and major legislation solution for mental health in China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 2010, 22 ( 4 ): 193-199.(in Chinese)

3. WHO. Mental Health Atlas 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005: 133-135.

4. Statistical Information Center of the Ministry of Health. Health statistics almanac of China in 2005. Beijing: China Union Medical College Press, 2006: 62-68. (in Chinese)

5. Brockington IF, Mumford DB. Recruitment into psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry, 2002, 180: 307-312.

6. Ma H, Liu J, He YL, Xie B, Xu YF, Hao W, et al. An important pathway of mental health service reform in China: introduction of 686 program. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 2011, 25 (10): 725-728. (in Chinese)

7. Pan ZD, Xie B, Zheng ZP. A survey on psychiatric hospital admission and relative factors in China. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine, 2003, 13 (5): 270-272. (in Chinese)

8. NPC Standing Committee. Provisions and instructions on the mental health law (Drati). htip://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/xinwen/ lfgz/flca/2011-10 /29/content_1678355.htm. [Accessed 20 December, 2011] (in Chinese)

doi (combining all the papers in the Forum Section): 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.01.005

Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Correspondence: binxie64@gmail.com

- 上海精神醫(yī)學的其它文章

- · In This Issue ·

- A new mental health law to protect patients’ autonomy could lead to drastic changes in the delivery of mental health services: is the risk too high to take?

- Service availability, compulsion, and compulsory hospitalisation

- Mental health legislation needs to point to the future

- The proposed national mental health law in China: a landmark document for the protection of psychiatric patients’ civil rights