Carbon Footprint and Life Cycle Assessment of Organizations

Matthias Finkbeiner, Paul K?nig

1Department of Environmental Technology, Chair of Sustainable Engineering, Technical University Berlin, Office Z1, Strasse des 17. Juni, 10623 Berlin, Germany

Carbon Footprint and Life Cycle Assessment of Organizations

Matthias Finkbeiner1?, Paul K?nig1

1Department of Environmental Technology, Chair of Sustainable Engineering, Technical University Berlin, Office Z1, Strasse des 17. Juni, 10623 Berlin, Germany

Submission Info

Communicated by Zhifeng Yang

LCA of organizations

Carbon footprint of organizations

Scope 3

Supply chain

Value chain

When analyzing the environmental performance of products, it has become standard practice to use a life cycle perspective. For organizations (e.g. companies) such a life cycle or supply chain oriented assessment is not yet established as common practice. The discussions on the carbon footprint of organizations and the development of the so-called ‘supply chain’- or ‘scope 3’-standard of the GHG-Protocol promoted the future use of such an approach. At the level of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) a project has just been launched to develop an LCA standard for Organizations (ISO 14072), which will address the full set of environmental interventions, not only greenhouse gases. This paper proposes a corporate environmental footprint assessment methodology by adapting the mandatory elements (“shalls”) of ISO 14044 from products to organizations. Most requirements are applicable on both the product and organizational level, such as impact assessment, reporting and review requirements. Others were partially adapted from ISO 14044, such as system boundary or allocation procedures. A third group of aspects like e.g. comparisons based on a common function, i.e. product and service portfolio, were identified as methodological challenges. As far as the data demand is concerned, it was interesting to find that even the corporate accounting approach needs product level data and in that respect does not differ from the traditional life cycle approach. ? 2013 L&H Scientific Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

1 Introduction

In order to analyze the environmental performance of products, it has become standard to use a (holistic) life cycle perspective to capture all environmental impacts from resource extraction to disposal of the manufactured product. The benefits and the potential of the life cycle approach are not limited to an ap-plication on products. While the LCA methodology was originally developed for products, its application on the organizational level is getting more and more relevant. However, an LCA for an organization appears to be even more complex. There is more than one product life cycle to follow, as most organizations are engaged in many product life cycles to different degrees [1] and a large part of environmental impact can reside outside the organization’s gate [2], upstream and downstream the value chain.

The first considerations concerning organizational footprinting have been conducted in the early and mid-90s [3,4] but they never gained sufficient attention by science and industry to be further developed into a broadly applied standard. Now, after years of environmental management, organizations are in the process of adapting the life cycle approach on the organizational level.

The discussions on carbon footprinting of companies including their upstream and downstream supply chains (the so-called ’scope 3’ according to the GHG-Protocol) [5] revealed that these ’life cycle’ emissions can contribute significantly to the organizational footprint. The currently applied assessments of organizations mostly concentrate on a single aspect like carbon or water footprints. While it definitely is useful to explicitly cover specific, important environmental areas such as greenhouse gases and water, a holistic approach is needed in order to prevent trade-offs between different types of environmental impact. The purpose of this paper is to present a general and comprehensive approach by adapting LCA methodology on organizations.

Over the first decade of the 20thcentury, several organizational environmental footprint standards emerged. However, a review of selected existing standards by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission indicates that for companies the holistic approach is not yet really implemented [6]. More recently, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) approved a new project to work on additional life cycle assessment (LCA) requirements and guidelines for organizations. The standard starts from the notion that the benefits and the potential of the life cycle approach are not limited to an application on products. As the currently applied assessments mostly concentrate on a single aspect, the purpose of this new standard is to present a general and comprehensive approach by adapting LCA methodology on organizations.

The document ISO 14072 is supposed to be a Technical Specification (TS) called ’Life Cycle Assessment – Additional Requirements and Guidelines for Organizations’. The main goal is to provide additional guidance to organizations for an easier and more effective application of the international standards of life cycle assessment ISO 14040 [7] and ISO 14044 [8,9] on the organizational level including the advantages that LCA may bring to organizations, the system boundaries and the limitations regarding reporting, environmental declarations and comparative assertions. It is intended for any organization that is interested in applying LCA. It is not intended for ISO 14001 [10] interpretation and covers the goals of ISO 14040 and 14044.

In this paper, an approach is proposed how such an adaptation of the originally product based method of life cycle assessment to an application on organizations could be achieved (see following Section 2). The results of this analysis are presented in Section 3. Several methodological aspects were identified that still represent challenges for an organizational LCA (OLCA). They are discussed in more detail in Section 3.2.

2 Method

To draft a holistic OLCA standard, ISO 14044 [8] was taken as the backbone for this research. The basic idea was to extract all the requirements of the product standard and to assess, if and how they can be transferred to an application on organizations. For this purpose, all the requirements of ISO 14044 indicated by those provisions that contain “shalls” were extracted from the standard. For each of the, the feasibility for transformation or adaptation from product context to organization context was checked.

After this exercise, the resulting ISO 14044 derived ‘backbone’ requirements for organizations were compared to the requirements of the WBCSD/WRI GHG-Protocol Scope 3 Standard [11] and the current draft of the EU Organizational Environmental Footprint method [12]. For aspects that are not yet satisfactorily covered from the ISO 14044 ‘backbone’ requirements, complementary requirements from the other standards were used to assemble a comprehensive OLCA standard that follows the life cycle principle.

Discussing all requirements of this comprehensive methodology in detail goes beyond the scope of this paper, but the general results and observations are presented in section 3. This includes some thoughts on the remaining challenges for mainstreaming OLCA.

3. Results

The result presentation is structured in two subsections: the first subsection deals with the results of the applicability analysis of ISO 14044 for organizations (see section 3.1) and the second subsection presents the remaining methodological challenges (see section 3.2).

3.1 From product to organization - transfer of requirements

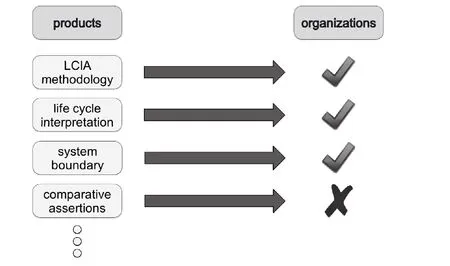

The overall process how the different product originating requirements were transferred to organizational context is schematically presented in Fig. 1. For example, all the requirements on the impact assessment (LCIA methodology in Figure 1) like “The selection of impact categories, category indicators and characterization models shall be both justified and consistent with the goal and scope of the LCA” [8] or “The selection of impact categories shall reflect a comprehensive set of environmental issues related to the product system being studied, taking the goal and scope into consideration.” [8] can be easily and directly applied to OLCA as well. The only adaptation needed is the substitution of the term ‘product system’with ‘organization’.

It was found overall, that the transformation of the ISO 14044 “shalls” from products to organizations works surprisingly well, because many requirements are independent from the product definition. Out of the 33 paragraphs containing requirements extracted from ISO 14044 (e.g. system boundary or mandatory elements of LCIA), more than 90% (30 paragraphs) were basically transferable from products to companies.

The three sections which did not apply are all related to the topic of comparative assertions. While for product LCA, the application of LCA to support so-called comparative assertions is a key feature that is implemented by the functional unit as a methodological solution to achieve comparability, this does not really work for organizations. The function of an organization is represented by its product and service portfolio (which would have to be used to quantify the “functional unit”). Different organzations have vastly variable portfolios. Thus, in a strict sense every organization has a different functional unit, making it hardly feasible to compare them.

In case two organizations operate and belong to the same sector, it is more likely that they have a comparable portfolio, or that at least certain business units are comparable. However, even within the same sector, the size, the location, the product segment, the vertical integration, the financial transactions and overall business model can be significantly different. As a consequence, comparative assertions with regard to organizations are not a robust and meaningful application at this point in time.

Fig. 1 Schematic ISO 14044 product to organization transformation approach and results

Transferring the remaining requirements into organizational context already resulted in a quite comprehensive and consistent OLCA guidance. Therefore, only very few requirements of the other standards are needed – if at all – to provide a proper OLCA standard. This leads to the conclusion and recommendation, that the development of the ISO specification of LCA for organizatiuons (ISO 14072) the existing ISO standards on LCA serve by far as the best seed documents. ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 represent not only the ‘constitution’ for product applications [13], it was shown that they have the potential to serve the same purpose for organizational applications as well.

Despite the good transferability of the requirements, the analysis revealed a specific set of challenges for OLCA, which will be further elaborated in the next section.

3.2 Methodological challenges

Methodological challenges of the life cycle assessment of products, like drawing the system boundary, securing sufficient data quality or comprehensive impact assessment apply for organizations as well. In cases, they can be even more difficult to address, because organizations are often more complex than single product life cycles. To accommodate the higher complexity, especially of system boundaries, the GHG Protocol provides practitioners with a good illustration of possible inclusion criteria for entities and processes, in form of the consolidation approaches, whereby the organization’s boundaries, i.e. scope 1 and 2, are defined [11].

In addition 15 reporting categories (purchased goods and services, capital goods, fuel- and energyrelated activities (not included in scope 1 or scope 2), upstream transportation and distribution, waste generated in operations, business travel, employee commuting, upstream leased assets, downstream transportation and distribution, processing of sold products, use of sold products, end-of-life treatment of sold products, downstream leased assets, franchises, investments) were introduced, to provide an overview of various sources for environmental impact outside the organization’s own facilities up- and downstream the supply chain. They represent the scope 3 of an organization. Organizations can go through these categories and select those which apply to them and thus gain an overview of their possible environmental impact.

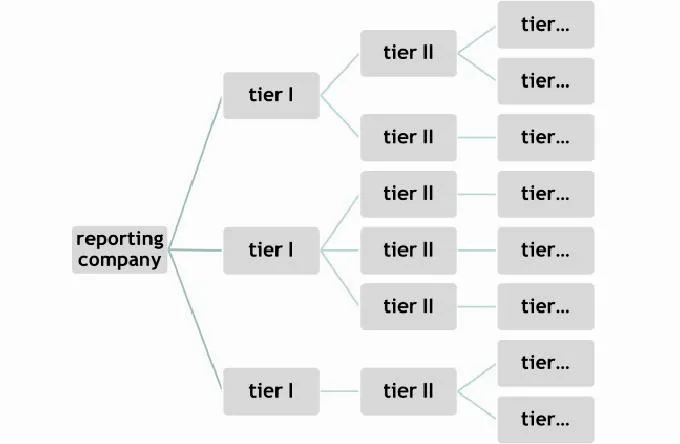

Fig. 2 Accounting type system boundaries

Besides the transferred challenges, conducting an organization wide assessment of environmental impacts can also be advantageous. A car plant for example manufactures many different models. If only one is assessed, allocation would have to take place for every machine and resource used for more than one production line, resulting in many allocation problems. If the whole plant would be assessed, no internal allocation problem would arise because an OLCA integrates over the whole organization and every process involved in it. This, however, does not mean allocation problems disappear generally but the reporting organization outsources the problem of allocation to partners in the supply chain.

One methodological challenge, e.g. the definition of the system boundary, will be discussed exemplarily in some more detail. Setting the system boundary is a decisive step concerning the accuracy and representativeness of the modeled system, be it a product life cycle or an entire organization. Based on the GHG-Protocol [11] the system boundaries are chosen by consolidation approach. As a consequence, different consolidation approaches (e.g. operational control or equity share) can lead to different systems and different shares of accounted environmental impact.

Independent from the consolidation approach, there are two distinct variations of constructing the system. On the one hand, the adaptation of the LCA methodology to organizations focusses on the inclusion of all products and services provided by an organization’s portfolio into the assessment. On the other hand an accounting approach derived from financial accounting using organizational suply chain data rather than product data. Using the latter means that the reporting organization collects the scope 1 and scope 2 emissions (i.e. direct, on-site activity related emissions, such as burning of fuels or electricity and heat consumption) from every organization within the supply chain. Aggregated over the supply chain, this leads to a scope 3 perspective. As an alternative the reporting organization could collect the scope 3 emissions of all their first tier suppliers.

An exemplary upstream supply chain is shown in Fig. 2. The aggregated emissions from tier I, tier II and tier n suppliers constitute the reporting organization indirect upstream emissions. Requesting these emissions all along the supply chain as well as assessing their own scope 1 and scope 2 emissions and use-related emissions in case of sold products and services then would be used to compose the OLCA.

While such an approach may seem plausible at first sight and is commonly proposed by scholars who come from an organizational background, it makes no real sense in practical application. First of all, it is difficult to guarantee consistency in the consolidation methodology used by different companies in the supply chain. Secondly, allocation of scope 1 and 2 emissions is ususally necessary, because suppliers do not necessarily work exclusively for the reporting organization. In that sense, only a share of thesuppliers’ total environmental impact should be accounted for by the reporting organization. As a consequence, such an organisational accounting approach leads double-counting and does not reflect the supply chain burdens of a company in a proper way. Companies buy products from their suppliers, they do not usually buy the whole supplier company.

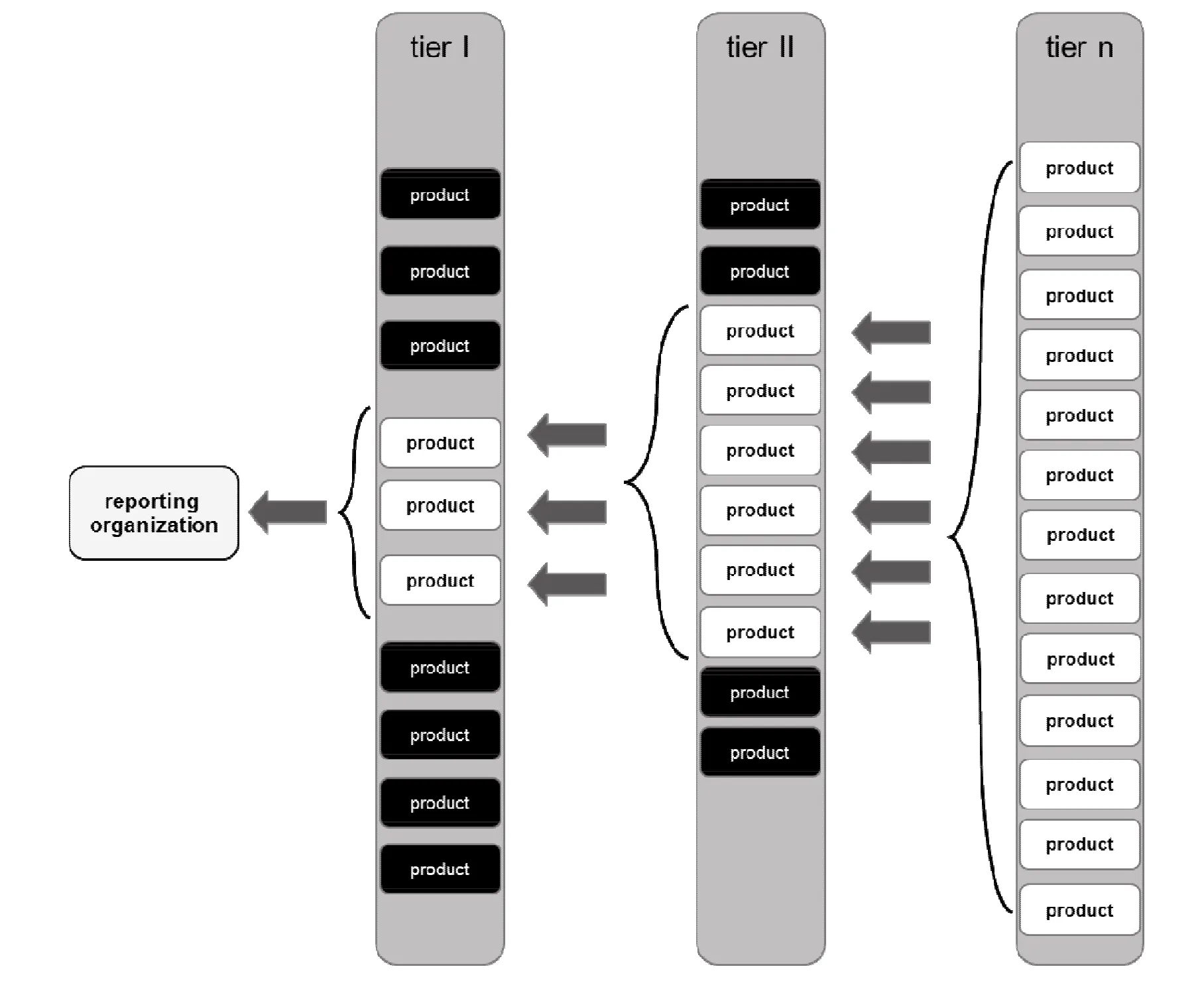

Therefore, even for an OLCA, the product perspective is indispensable when assessing the supply chain of organization. This is schematically shown in Fig. 3, which includes a possible upstream supply chain composed of tier I, tier II and tier n suppliers. Each tier produces a number of products for the following tier until the products are delivered to the reporting organization. As long as all products from tier I, II and n are all completely involved in the reporting organization’s product portfolio (light shade), no allocation problems arise. However, if some products are not delivered to the reporting organization (black shade) but are part of the suppliers’ scope 1 and 2 emission spectrum, they should not be accounted for. Hence an allocation of the supplier’s scope 1 and 2 emission spectrum has to take place in order to adjust the aggregated emissions to the reporting organization’s purchased share.

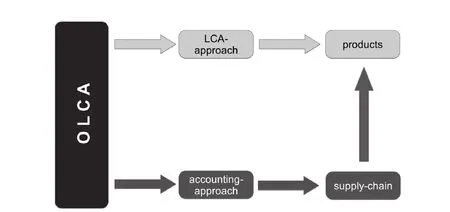

To do so, product level data have to be used and this represents the interface to the domain of product LCA. As a consequence, the (theoretical) advantage of OLCA of not having to cope with numerous product life cycles may not apply anymore. Fig. 4 shows the schematic interface between corporate accounting and product perspective. From a conceptual perspective, there is no organizational LCA without product LCAs.

A sensible way of coping with this difficulty could be to use the scope 3 categories to gain an overview over the possible indirect environmental impacts and use generic product LCA data to model them. For those products and impacts which contribute significantly to the overall OLCA burden, the suppliers can be approached to gain access to their specific data for updating the OLCA profile and for identifying options to reduce impact by product or process optimisation of the existing supplier or choosing an alternative supplier with better performance.

Another aspect of methodological challenges was revealed when analyzinng the principles of LCA. Regarding the principles of LCAs according to ISO 14040, paragraph 4.1, only the principle of relative approach and functional unit was found to be non-transferable. All other principles have their equivalent in the world of organizations. The life cycle principle can be followed regarding products as well as regarding organizations, transparency and comprehensiveness are needed for the review procedure and to satisfy stakeholders and interested parties. The iterative approach can be applied as well and the environment is still the methodology’s focus. Finally, the scientific approach should also be integral to OLCAs in the same manner as to product LCAs.

As indicated above, the relative approach and the definition of the functional unit are a challenge for OLCA, because the function is quite different on organizational level compared to products. The functional unit was introduced in LCA to achieve comparability. As indicated above, comparability in OLCA seems not really consistently possible. Therefore, the functional unti concept might be transferred to OLCA by renaming it to reporting unit or portfolio or organizational unit.

Rather than comparing different organizations, the continuous improvement of organizations with a regular assessment of the environmental performance of an individual organization over time – performance tracking – seems a more promising application. This is also a good approach to boost new improvement opportunities of established environmental management systems beyond the factory gates. While doing so, it is important to set specific procedural targets to minimize the organization’s environmental impact over time.

Fig. 3 Product type system boundaries

Fig. 4 OLCA requires a consistent approach at the interface of corporate accounting with products

Last, but not least, the methodological challenge to deal with immaterial products, like loans, funds, investments or leased assets has to be addressed. This is relatively new ground for LCA and a general approach to cover and allocate financial products needs to be developed. As an example, the investment category used by the GHG Protocol is not yet satisfactory, because the investor shall only account for scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of the investees, whereas scope 3 emissions are disregarded for simplification although they can often predominate the total impact.

4. Conclusion and outlook

The benefits and the potential of the life cycle approach are not limited to the application on products. It was shown that the development of a standard or guideline for organizational LCA is largely possible based on the transfer of the originally product specific requirements (“shalls”) of ISO 14044 into organization related requirements. However, there are also still challenging aspects for a holistic OLCA standard, such as the definition of the system boundaries, the accounting for investments and the comparability of different organizations. The accounting approaches of equity share or operational control can both lead to an omission of significant environmental impacts and are not sufficient to support a robust and consistent system boundary.

Independent from the accounting approaches of equity share or operational control, it seems impossible to define OLCA system boundaries without decidedly assessing the life cycles of the product portfolio and the application of product level data from LCA databases. Due to the unresolved challenges in comparing different organizations, an OLCA should for now focus on performance tracking for individual organizations instead of comparing different organizations. While doing so, it is important to set specific procedural continual improvement targets to reduce the organization’s environmental impact over time.

For the future, we think that further case studies and research are needed to refine the methodology with regard to the key remaining challenges of OLCA. For application, we think that the following uses of OLCA are most promising:

· comprehensive assessment of all environmental aspects of an organization to complement single issue footprints

· performance tracking for continual improvement of an organizations footprint

· identification of environmental hotspots of an organization beyond the factory gate

· assessment of complete product portfolio to support prioritization of product LCAs

The publication of the new Technical Specification ISO 14072 is expected for 2014 and will support the mainstreaming of organizational LCA. Another relevant initiative, the UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative, has also just decided to launch the topic of LCA of organizations as one of their so-called flagship projects.

Acknowledgements

Part of this work was supported by the German Research Foundation as part of the Collaborative Research Center 1026: Sustainable Manufacturing.

[1] Finkbeiner, M., Wiedemann, W., and Saur, K. (1998), A comprehensive approach towards product and organisation related environmental management tools,The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 3(3), 169-178.

[2] Downie, J. and Stubbs, W. (2011), Evaluation of Australian companies’ scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions assessments,Journal of Cleaner Production, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.09.010.

[3] Mueller-Wenk, R. and Braunschweig, A. (1993),?kobilanzen für Unternehmungen: eine Wegleitung für die Praxis, Bern: Paul Haupt.

[4] Taylor, A.P. and Postlethwaite, D. (1996),Overall Business Impact Assessment (OBIA), Proceedings of the 4th SETAC Case Study Symposium, 03.12.96, Brussels.

[5] Finkbeiner, M. (2009), Carbon footprinting – opportunities and threats,The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 14(2), 91-94.

[6] Chomkhamsri, K. and Pelletier, N. (2011),Analysis of Existing Environmental Footprint Methodologies for Products and Organizatinos: Recommendations, Rationale, and Alignment, Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/Deliverable.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2012.

[7] ISO 14040. (2006),Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment – Principles and Framework, Switzerland: Geneva,

[8] ISO 14044. (2006),Environmental Management – Life Cycle Assessment ? Requirements and Guidelines, Switzerland: Geneva,

[9] Finkbeiner, M., Inaba, A., Tan, R.B.H., Christiansen, K., and Klüppel, H.J. (2006), The new international standards for life cycle assessment: ISO 14040 and ISO 14044,The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 11(2), 80-85.

[10] ISO 14001. (2009),Environmental management systems – Requirements with guidance for use, Switzerland: Geneva,

[11] GHG Protocol. (2011),GHG Protocol: Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard, http://www.ghgprotocol.org/files/ghgp/Corporate%20Value%20Chain%20(Scope%203)%20Accounting%20and%20Repo rting%20Standard.pdf. [Accessed 17.08.2012].

[12] EU Commission. (2012),Organisation Environmental Footprint (OEF) Guide,

[13] http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/footprint/OEF%20Guide_final_July%202012_clean%20version.pdf. [Accessed 17.08.2012].

[14] Finkbeiner, M. (2013), From the 40s to the 70s—the future of LCA in the ISO 14000 family,The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18, 1-4.

10 January 2013

?Corresponding author.

Email address: matthias.finkbeiner@tu-berlin.de

ISSN 2325-6192, eISSN 2325-6206/$- see front materials ? 2013 L&H Scientific Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

10.5890/JEAM.2013.01.005

Accepted 25 February 2013

Available online 2 April 2013

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2013年1期

Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management2013年1期

- Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management的其它文章

- Global Gold Mining: Is Technological Learning Overcoming the Declining in Ore grades?

- Multi-scale Input-output Analysis for Multiple Responsibility Entities: Carbon Emission by Urban Economy in Beijing 2007

- Keeping the Books for the Environment and Society: The Unification of Emergy and Financial Accounting Methods

- Analysis of the Scientific Collaboration Patterns in the Emergy Accounting Field: A Review of the Co-authorship Network Structure

- Environmental Performance and Biophysical Constrains of Italian Agriculture Across Time and Space Scales

- Sustainability Ethics and Metrics: Strategies for Damage Control and Prevention