Chairman's government background,excess employment and government subsidies:Evidence from Chinese local state-owned enterprises

Xiongyun Wng,Shn Wng

aSchool of Accounting,Zhongnan University of Economics and Law,China

bAntai College of Economics and Management,Shanghai JiaoTong University,China

Chairman's government background,excess employment and government subsidies:Evidence from Chinese local state-owned enterprises

Xiongyuan Wanga,Shan Wangb,*

aSchool of Accounting,Zhongnan University of Economics and Law,China

bAntai College of Economics and Management,Shanghai JiaoTong University,China

A R T I C L EI N F O

Article history:

Accepted 28 August 2012

Available online 21 December 2012

JEL classification:

D73

G28

G32

H2

Local state-owned enterprises(SOEs)in China continue to face government interference in their operations.They are influenced both by the government's“grabbinghand”andbyits“helpinghand.”O(jiān)urstudyexamineshowSOEchairmen with connections to government influence their firm's employment policies andthe economicconsequences of overstaffing.Using asample of China's listed localstate-ownedenterprises,we findthatthescaleofoverstaffingintheseSOEs isnegatively related to the firms'political connections to government.However, thisrelationshipturnspositivewhenthe firm'schairmanhasagovernmentbackground.Appointing chairmen who have government backgrounds is a mechanism through which the government can intervene in local SOEs and influence firms'staffing decisions.We also find that in compensation for the expenses of overstaffing,local SOEs receive more government subsidies and bank loans. However,the chairmen themselves do not get increased pay or promotion opportunities for supporting overstaffing.Further analysis indicates that whereasthe“grabbinghand”ofgovernmentdoesharmtoafirm'seconomicperformance,the“helping hand”provides only weak positive effects,and such governmentinterventionactuallyreducestheefficiencyofsocialresourceallocation.

?2012 China Journal of Accounting Research.Founded by Sun Yat-sen University and City University of Hong Kong.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

1.Introduction

Companies normally make decisions to maximize their profits,so managers would not be expected to accept projects that harm their firm's economic performance.However,when managers of state-owned enterprises(hereafter,SOEs)make decisions about employment,they tend to hire more people than necessary, because these entities are especially established by the government to enhance the country's rate of employment(Sappington and Stiglitz,1987;Boycko et al.,1996;Dong and Putterman,2001).Although a number of studies(Dewenter and Malatesta,2001;Dong and Putterman,2003)have demonstrated that political pressure or government intervention causes excess employment in SOEs,previous researchers do not clearly explain the connection between government intervention and overstaffing.In this study,we attempt to fill this void.

Our study addresses questions such as how governments intervene in corporations and by what mechanism governments influence SOEs to employ extra people.We consider that politicians may choose to focus their interventions on SOEs because it is much more costly for them to interfere in private firms.Boycko et al. (1996)argue that politicians cause government-owned firms to employ a surplus of workers.Similarly, Dewenter and Malatesta(2001)find that government-sponsored firms tend to use more labor than their private-sector counterparts,because private firms are more difficult for governments to influence.Also,it has already been proven that appointing corporate executives who have a government background is an effective way for the government to influence SOEs.The power of politicians to appoint SOE chairmen and to control costs or rewards for businesses open up opportunities for governments to exert direct influence on SOEs(Tenev et al.,2002).More importantly,we argue that most SOE executives are motivated to earn more money and gain more opportunities for promotion,and these motives can lead them to facilitate government priorities.

Political connections are considered a very important factor influencing the way firms perform(Fan et al., 2007)and the question naturally arises as to whether political connections affect company employment decisions.There are several reasons why China provides a natural laboratory for examining the effects of political connections on firm behavior.(1)State ownership is prevalent and the state sector is far from homogeneous, as most SOEs are controlled either by the central government or local governments(provincial or county level).(2)The government maintains heavy control over the economy and it often uses SOEs to serve political and social objectives,such as reducing unemployment or fiscal deficits.(3)The market for chairmen is underdeveloped in China,with many managers possessing close political ties to local and central governments but lacking professional qualifications or managerial experience.

Therefore,we predict that examining the political connections of SOEs may provide answers for our questions concerning appointed chairmen and company employment policies.We investigate these possibilities further by examining a sample of local SOEs and considering a new determinant of overstaffing that previous studies have not explored.

Although we mainly focus on the effect of chairmen with government backgrounds on excess staffing,we address several other issues as well.Particularly,we investigate whether overstaffing adversely affects corporate performance(Li and Liang,1998;Xu et al.,2005;Zeng and Chen,2006;Xue and Bai,2008).We ask what bene fits a corporation will receive if it hires more people than it really needs.Lin and Tan(1999)show that firms that practice overstaffing receive compensation in the form of lower taxes,more government grants and preferential treatment in competition for contracts.We expect that the problems of overstaffing may result from an exchange of bene fits between firms and the government.If a firm agrees to employ redundant workers,then that firm will enjoy opportunities for easy access to bank loans and grants or preferential tax treatment.The firm receives such bene fits,but do the firms'executives gain any bene fits?Another concern of our study is to determine whether corporate executives,especially chairmen,receive promotions or higher pay for supporting excess employees.

To answer these questions,we manually collect detailed information on the chairmen of all of the local SOEs listed in A-share markets in China from 2004 to 2009.This information includes the chairmen's past employment records,including any background they may have in government.We classify a company as being politically connected if its chairman is a current or an ex-government official.Then we compare the hiring practices of politically connected companies with those of other companies.Our findings areas follows.First,after controlling for other factors that influence firms'staffing,we find that having politically connected chairmen has a significant positive relationship with excess employment by local SOEs.We consistently find that the overstaffing problems in firms run by politically connected chairmen are more serious than in firms that are otherwise similar.Second,our analysis of the economic consequences from such political influence shows two main effects.The evidence indicates that local SOEs with chairmen who have government backgrounds receive more bank loans and more government grants than those without such a political connection.However,we find no evidence that excess staffing is positively related to debt financing or to government subsidies.Also,we find that excess employment is negatively related to the chairman's prospects for promotion,which is contrary to our prediction.Concerning the chairman's compensation, a firm's overstaffing has a negative effect on its chairman's total compensation,but a positive effect on the chairman's relative compensation.

To better understand the overstaffing problem of China's local SOEs,our study(1)performs additional analysis on the connections between excess employment and firm performance(or labor costs),and(2) investigates how the social objectives of politicians influence the appointment of politically connected CEOs.

By controlling for other factors that influence firm performance(labor costs),we find that a firm's scale of overstaffing is negatively related to its accounting performance and positively related(to a significant degree) to its total labor costs.Finally,a listed company's chairman is more likely to be politically connected when the company belongs to a region with a lower per capita GDP and a higher unemployment rate.

Our study contributes to several strands of the literature.First,the evidence from this research enriches our understanding by showing how the appointment of chairmen with government backgrounds helps the government to promote overstaffing by SOEs.Prior studies(Shleifer and Vishny,1994;Dong and Putterman,2003; Lin and Tan,1999)have focused on government interventions that affect excess employment.However,we concentrate on how governments actually influence corporations to hire more people.We find that appointing politically connected chairmen is the main mechanism through which the government intervenes in firms to promote the hiring of more employees.

Second,our paper adds to a growing literature that explores the effects of political connections on business. Political connections are already considered an important factor in the valuation offirms(Fisman,2001; Johnson and Mitton,2003),in company performance(Fan et al.,2007)and in mode of operations(Bertrand et al.,2006;Li et al.,2008;Claessens et al.,2008).However,the question of whether or how the political connections of company chairmen affect excess employment is not well explored.One of the few studiesexamining this issue is that of Liu et al.(2010).Using cross-sectional data,these authors find that the effect of political connections on employee allocation efficiency is influenced by the firm's ultimate controller. However,Liu et al.(2010)do not examine the economic consequences of excess employment.This study attempts to fill this void in the literature and examine the effects of excess employment on firms in greater depth.

Finally,our paper contributes to the literature on how government policy affects business in general.The evidence from our paper supports both the“grabbing hand”model(showing how politicians can intervene at the expense of business activities)and the“helping hand'model(showing how politicians can provide privileges and benefits to corporations)(Shleifer and Vishny,1994).We consider government pressure for excess employment as a typical example of the“grabbing hand”and compensatory bank loans or government subsidies as examples of the“helping hand.”

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.Section 2 discusses the prior literature and develops the hypotheses.Section 3 describes the sample and variables,and outlines the econometric specifications.Section 4 presents the data and descriptive statistics.Section 5 empirically tests the hypotheses and reports the results. Section 6 provides conclusions.

2.Institutional background and hypotheses

In this section,we discuss the institutional background of China's business environment and develop our hypotheses regarding the effects of political connections on excess employment and on the economic consequences of the overstaffing problem.

2.1.Background

During the economic reforms of the 1980s,the Chinese government launched a program allowing bureaucrats to quit their government positions and join the business community,a phenomenon that later came to be known as“xiahai”(jumping into the sea).Starting in the mid-1980s,many government agencies began to establish business entities and many bureaucrats became managers of these businesses(Li,1998).Although these ex-bureaucrats have officially quit the government,they still keep good relations with their friends or ex-colleagues in government.These ties help to keep government and business linked together.

As a relationship-based transitional economy,Chinese society is pervaded by the ubiquitous phenomenon of guanxi(or relationships).The word describes a subset of Chinese personal connections in which one individual is able to prevail upon another to perform a favor or service(Chung and Hamilton,2002).Political connections are one type of“guanxi.”The state gives preferential treatment to firms with political connections and uses its political power to intervene in the firms'operations or corporate governance.

As the promotion of regional officials to higher-ranking positions depends largely on their region's economic growth,or GDP,these officials have an interest in keeping regional rates of development and employment high during their periods in office(Li and Zhou,2005).Therefore,officials at all levels of government have an incentive to intervene in SOEs and use these firms to help solve political and social problems.

2.2.Hypotheses development

In this section,we develop our hypotheses concerning the relationships between excess employment in local SOEs and the government backgrounds of SOE chairmen.

2.2.1.Chairman's government background and excess employment

A series of studies beginning with Roberts(1990)point out that political connections in corporations are a worldwide phenomenon in both developing and developed countries.However,such connections are more common in countries that are perceived as highly corrupt or that impose restrictions on foreign investments by their citizens,than in countries with more transparent systems(Faccio,2006).

What are the causes of political relations in business?There are two explanations.First,concerning the government's“helping hand,”political connections are a kind of reputation-building mechanism(Luo and Zhen, 2008).Firms take this mechanism as a kind of social resource,with which they can seek benefits or rents directly from the authorities(Michelson,2007;Yu et al.,2010).Second,in view of the government's“grabbing hand,”political connections are a substitute for the presently flawed institutions in transitional countries.If a company has a good political connection with the government,it can effectively defend itself against infringements that the authorities seek to impose on companies.A number of recent studies(Chen et al.,2005;Faccio, 2006;Li et al.,2006;Yu and Pan,2008)suggest that private firms are far more likely to participate in political affairs in countries with high levels of corruption and low levels of property protection(Chen et al.,2005; Faccio,2006;Li et al.,2006).Under conditions of discriminative policies,private entrepreneurs search for new approaches to protect themselves.Many company managers feel it has been proven that keeping a close connection with the government is the most effective means of self-protection.Obviously,this view emphasizes the role of political connections for resisting the government's“grabbing hand.”However,the Chinese government's pressure to hire extra employees is a typical instance of the grabbing hand,because overstaffing results in higher labor costs and worsens firm performance.Some firms might hope that political connections will protect them from such pressure,but we argue that excess employment has a negative relationship with political connections.

Although theoretical analysis suggests that political connections negatively affect a firm's scale of overstaffing,there is little empirical evidence for this argument.A few empirical studies examine the relationship between political connections and excess employment and show that politically connected corporations undertake too many tasks for politicians(Bertrand et al.,2006).Business managers do this because politicians require their closely connected firms to help solve unemployment problems by hiring extra workers (Bennedsen,2000;Yuan,2011).

To work out these contradictory results concerning political connections,the following questions need clarification.In what kinds offirms is the government likely to interfere?Also,through what kinds of political connections can the government most effectively intervene?

Prior studies have already provided us the answer to the first question.Local governments often choose to intervene in SOEs(Sappington and Stiglitz,1987;Boycko et al.,1996).These researchers believe that SOEs are much more easily influenced by government intervention and much more likely to pursue social objectives rather than maximizing profits.As it is more costly for the government to intervene in private firms,SOEs usually sustain a much greater burden of overstaffing than other firms(Dewenter and Malatesta,2001;Zeng and Chen,2006).

As to the second question concerning the means of intervention,recent studies show that appointing people with government backgrounds as SOE chairmen helps politicians to achieve their employment goals.In China's gradual process of SOE reform,the government still firmly controls appointments and dismissals of key personnel in these companies(Qian,1995).Although each listed firm has a board of directors,the chairmen of SOEs are generally nominated by the government and then rubber-stamped by the board.These chairmen,especially those who have political connections,enjoy the same promotion and compensation mechanisms as politicians.Like politicians,they are affected by their region's performance in various political and social objectives.They feel it is important to improve the employment rate under their jurisdiction.In conclusion,through appointing politically connected chairmen,the government achieves its intervention for excess employment by local SOEs.

The above analysis leads to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.Local SOEs with chairmen who have a government background are more likely to support excess employment.

2.2.2.Economic consequences of excess employment:firm/chairman level

If a chairman who has a government background does not gain any personal benefits,why would he voluntarily act as the link for government intervention in promoting excess employment?If the government does not compensate local SOEs for their losses from overstaffing,why would these firms employ more people?We predict that an exchange of benefits exists among local governments,chairmen and local SOEs.

Concerning the chairman,it may be that he is willing to help the government intervene in his firm in exchange for higher pay or more promotion opportunities(Brickley et al.,1999;Gillan et al.,2009).However,Cao et al.(2012)find that CEOs with a higher likelihood of political promotion have lower pay levels, which shows that political promotion could be a substitute for pay.Chairmen are judged by their firm's economic performance,but the promotion and the compensation of politically connected chairmen are more affected by their performance toward various political and economical goals such as growth in GDP or the employment rate(Liu,2005).If a chairman is interested in political promotion,then he exhibits a politician's objective function:he tries his best to cater to the will of the government(Zhang,1999;Chen et al., 2008).

Consequently,if a politically connected chairman facilitates the government's agenda for overstaffing,we expect there is a reward of promotion or higher pay for the chairman.We also expect that the relationship between excess employment and the chairmen's promotions(or compensation levels)will be strongest in politically related firms.

In terms of the firm,local SOEs may receive some policy favors for supporting excess employment.Prior studies conclude that redundant employees cause either increased labor costs(Zeng and Chen,2006)or decreased firm performance(Li and Liang,1998;Xu et al.,2005).If the government does not grant these firms some benefits,the firms may sustain losses and suffer severe financial problems in the short run.Hence,firms with redundant employees request the government to offer some policy favors.Consistent with this argument, Lin and Tan(1999)demonstrate theoretically that in exchange for supporting redundant workers,the enterprises bargain with the government for ex ante policy favors,such as low-interest loans,tax reductions,tariffprotections,legal monopolies,and so on.Furthermore,an empirical study by Xue and Bai(2008)uses Chinese data and finds that firms with redundant workers receive more government subsidies.

A number of studies find that political connections play the role of a“helping hand”for firms in transitional countries.Chen(2003)and Bertrand et al.(2006)show that politicians give aid to politically connected firms.Similarly,Wu et al.(2009)demonstrate that chairmen with experience working in government have a positive relationship with the authorities and smaller tax expenses.Empirical evidence(Johnson and Mitton, 2003;Faccio,2006;Claessens et al.,2008)indicates that politically connected firms have greater access to debt financing than their non-connected peers.

Therefore,we argue that if local SOEs take on excess employees,they may be compensated for their expenses by gaining preferential access to financing and government subsidies.Additionally,a chairman's government background will strengthen the positive political connection,allowing more debt financing or grants.

The above analysis leads to our second hypothesis,which is expressed in two parts:

Hypothesis 2A.Chairmen in firms with excess employment are more likely to receive higher pay or promotions,and this likelihood is higher if the chairman has a government background.

Hypothesis 2B.Firms with excess employment are more likely to have better access to debt financing or government subsidies,and this likelihood is higher if the chairman has a government background.

3.Research design

3.1.Sample selection

To test these hypotheses,we restrict our focus to A-share local SOEs listed on China's stock markets,whose ultimate owners did not change from 2004 to 2009.Our sample period begins in 2004 because it was not until this year that the CSRC(China Securities Regulatory Commission)explicitly required listed corporations to disclose their executives'work experience in annual reports,including CEOs'biographical profiles,from which we can obtain information about chairmen's government backgrounds.Also,listed firms began to formally disclose their ultimate controllers in annual reports starting in 2004.

Our study calls for identifying local SOEs according to the identity of their ultimate controllers. The information on SOE controllers is gathered from the CCER China stocks database,which provides detailed information on the ownership of China's ten largest shareholders and the ultimate shareholders of stock market-listed firms.The CCER classifies firms into the following three types: (1)local SOEs that are owned by various local governments,(2)central SOEs that are owned by the central government,and(3)non-state firms(or private firms),whose ultimate owners are nongovernment units such as individual entrepreneurs.In this study,we mainly focus on local SOEs. We differentiate between central and local SOEs because they are affected differently by different levels of government.

We manually collect the chairmen's information from the CSMAR financial database,which provides detailed information including age,gender,education,professional background and employment history on most corporate executives.We also examine the credibility of this personal information through Internet searches.According to each CEO's profile information,we traced their political connections by examining whether he/she is currently or was formerly a government official.

The accounting and financial data of listed firms was also obtained from the CSMAR database.For our tests,we need lagged firm performance information,so this data starts from 2003.Within the sample,firms in the financial industry sector are excluded because their accounting measurements different from those of others.Furthermore,firms listed in the province of Xizang are also excluded because their macroeconomic data is not completely disclosed.We also exclude firms with fewer than 200 employees according to Zeng and Chen(2006).Finally,we also exclude firms with missing data on necessary variables.

For our tests of chairmen's government backgrounds and firms'excess employment,data on unemployment rates and per capita GDP for different regions in our sample period are retrieved from the China Statistical Year Book.

3.2.Models and variables

To test our hypotheses,we use the following three regression models.Model(1)tests the relationship between politically connected chairmen and their firms'excess employment for H1.Then models(2)and (3)test the economic consequences of excess employment for H2A and H2B,respectively.

where i denotes the sample firm and t denotes the year in the sample period.

3.2.1.Dependent and independent variables for model(1)

Excess employment(Exc_L),the dependent variable,is calculated as follows.According to the Jones model system,we use the following expectation model suggested by prior studies(Zeng and Chen,2006)to control for the determinants offirm's employees,for each firm i in year t:

where Act_L is the number of employees at the end of a fiscal year divided by the millions of dollars offirm sales,Size is the logarithmic transformation of total sales,AssetGrowth is the growth ratio of capital investment,SalesGrowth is the growth ratio of sales and FixedAssets is fixed assets divided by total assets.

Ordinary least squares is used to obtain estimates of a,b1,b2,b3and b4respectively.Then we define the prediction error as excess employment and construct two variables to measure excess employment.The first variable is Exc_L,which equals the prediction error if it is greater than 0,and 0 otherwise.The second variable is Exc_L_Dummy,which equals 1 if it is greater than 0,and 0 otherwise.We run a Tobit regression for the first measurement and a logistic regression for the likelihood offirms'excess employment.

Political connection(Political),the explanatory variable in Hypothesis 1,equals 1 if the chairman of the firm is a current or former government official,and 0 otherwise.To particularly examine the special role that the chairman plays in a firm's excess employment,we employ a variable,Gov_Political.If the firm's chairman is or ever was the head of the industry that his or her firm belongs to,the variable Gov_Political equals 1.This rating would apply,for instance,if a firm is classi fied in the textile industry and its chairman has worked as head of the government's department of textiles.

Following the example of prior studies on excess employment(Dewenter and Malatesta,2001;Xue and Bai,2008),we include variables in the model controlling for size,asset growth,sales growth,asset structure, performance,leverage and firm age.We also control for chairman duality,the stock percentage of the largest shareholder and regional institutional variables such as per capita GDP,unemployment rate and marketization index.To control for industry and year effects,industry and year dummies are also included.

3.2.2.Dependent and independent variables for model(2)

Pay and Promotion are the dependent variables in this model.DirectorPay1 is a continuous variable for the chairman's compensation.We define this variable as the logarithm of the chairman's compensation.As the compensation data for each chairman is not completely disclosed,we use the compensation of the firm's top three managers to proxy for it.We also employ another proxy variable(DirectorPay2)to measure chairmen'scompensation.Here,DirectorPay2=Ln(topthreemanager'scompensation/employeestotal compensation).

Promotion is a dichotomous measure for chairman promotion,which equals 1 when there is a promotion for the chairman of the firm i in year t,and 0 otherwise.

Drawing from previous research(Wang and Wang,2007;Fang,2009),we include the following control variables in the model:managerial ownership,chairman's age and tenure,chairman-CEO duality and thestock percentage of the largest shareholder.We also control for firm characteristics such as size,leverage and performance.Finally,year and industry dummies are also included.

3.2.3.Dependent and independent variables for model(3)

Debt and Subsidy are the two dependent variables in this model.Following prior studies(Faccio et al., 2006;Yu and Pan,2008),we employ three measures to capture debt financing:(1)Debt1,or debt maturity (defined as long-term debt plus the current portion of long-term debt divided by total debts);(2)Debt2,or short-term debt ratio(calculated as short-term debt divided by total assets);and(3)Debt3,or long-term debt ratio(calculated as long-term debt plus the current portion of long-term debt divided by total assets).

To examine the effect of excess employment on the receipt of government subsidies,we introduce the variable Subsidy.Government subsidies are calculated as the sum of direct government subsidies,financial refunds and tax refunds from the financial statements of the listed firms,divided by total assets(or net income).

For model(3),besides firm characteristics and year dummies,we control for different variables in debt and subsidy regressions.In the debt model,we include an industry variable that equals 1 if the firm is in a monopolized industry(e.g.,electric power,telecommunication,etc.),and 0 otherwise.In the subsidy model,we include marketization indexes according to Yu et al.(2010).

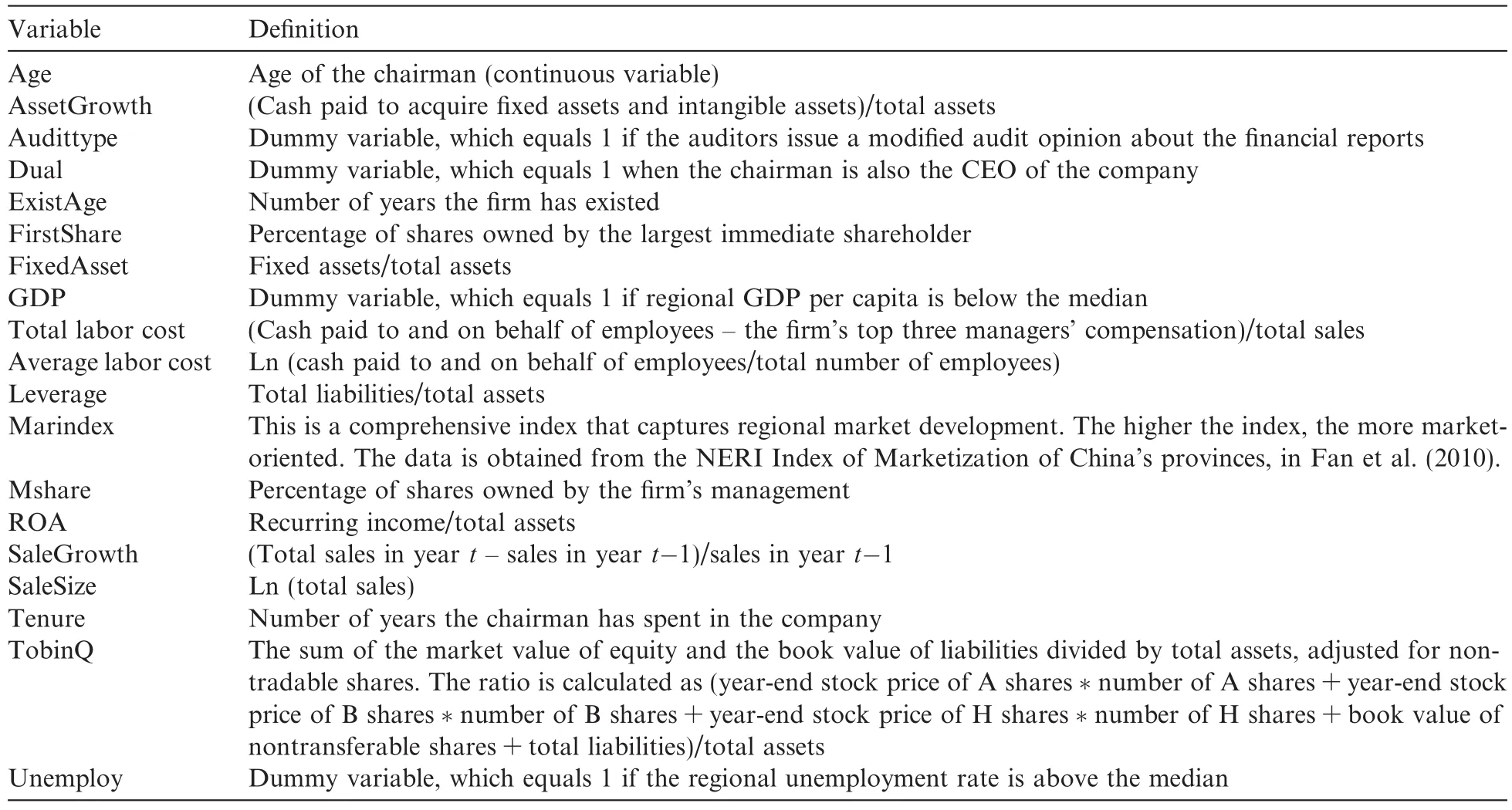

The definitions of the regression variables are provided in Appendix A.

4.Data and descriptive statistics

4.1.Definition of politically connected chairmen

There are various definitions of“political connections.”Siegel(2007)defines all CEOs who are from the same region as the president as politically connected CEOs.Others define CEOs who are friends,former colleagues and relatives of incumbent bureaucrats as politically connected CEOs(Fisman,2001;Johnson and Mitton,2003).However,in our paper,based on the analysis in Section 2.2.1 and on prior studies(Bertrand et al.,2006;Fan et al.,2007),we define politically connected CEOs as CEOs who are former bureaucrats. More specifically,this study focuses on firms'chairmen.We define chairmen with government backgrounds as chairmen who have government experience in the same industry in which they are now working.

4.2.Descriptive statistics

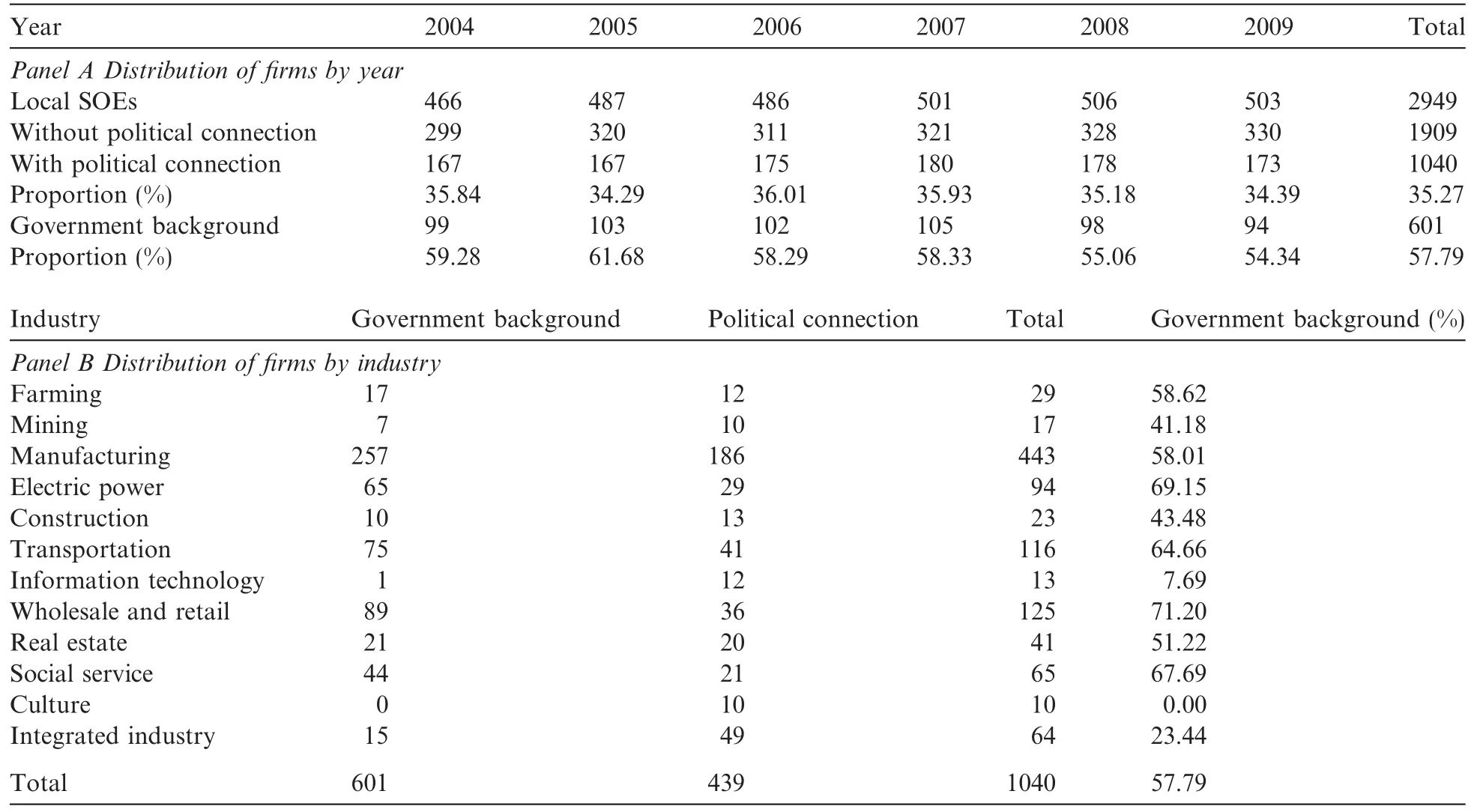

Table 1 provides a description of the sample.Panel A of Table 1 presents the number of politically connected chairmen of listed local SOEs between 2004 and 2009.This panel shows that the number of chairmen with government backgrounds is similar across this period and approximately 35.27%of the chairmen in our sample have political connections with the government.This suggests that the government maintains direct influence in a significant portion offirms through appointing politically connected chairmen.In the subsample of political connections(1040 observations),601 firms or 57.79%,have chairmen with government backgrounds.

Panel B reports the distribution of politically connected firms in different industry sectors,with the industry categories classified by the CSRC(China Securities Regulatory Commission).These results show that of the 1040 observations offirms with political connections,94 are in the natural resources sector,125 in the services and trade sector,443 in the manufacturing sector,65 in the public utilities sector and 116 in the transportation sector.Although the proportion of chairmen with political connections is similar across industries,there are relatively more politically connected chairmen in the manufacturing industries.Panel B also presents the percentage of chairmen with government backgrounds in these politically connected firms across industries.We can see from the table that in the agriculture,manufacturing,electric power,transportation,retail and utility industry sectors,over half of the corporations have chairmen with government backgrounds.

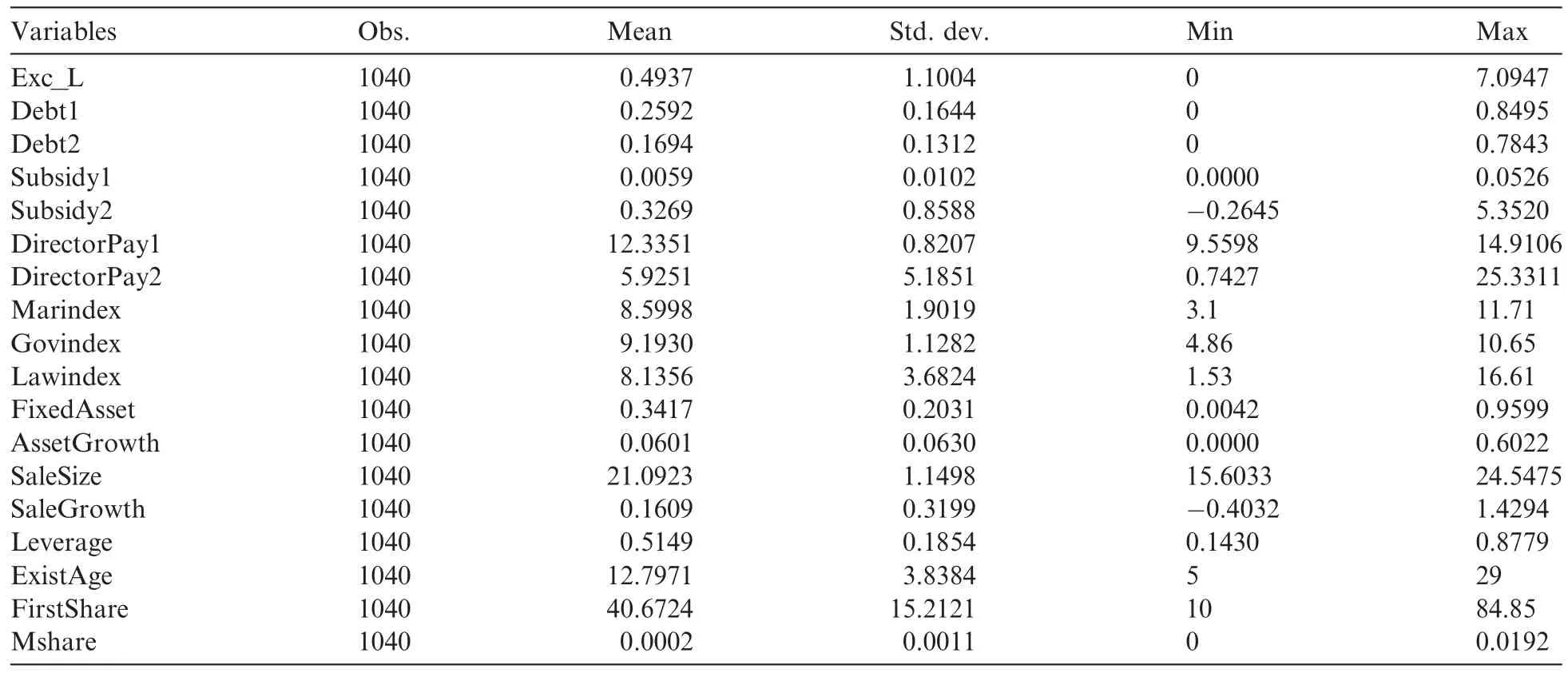

Table 2 provides the mean,standard deviation(std.dev.),minimum value(Min.),and maximum value (Max.)of the continuous variables for the subsample where firm chairmen are politically connected.The mean value for Exc_L is 0.49,suggesting that the average number of excess employees for every 1 million in sales is0.49.To reduce the influence of extreme observations in the results,we winsorize the continuous variables at the top and bottom 2%.

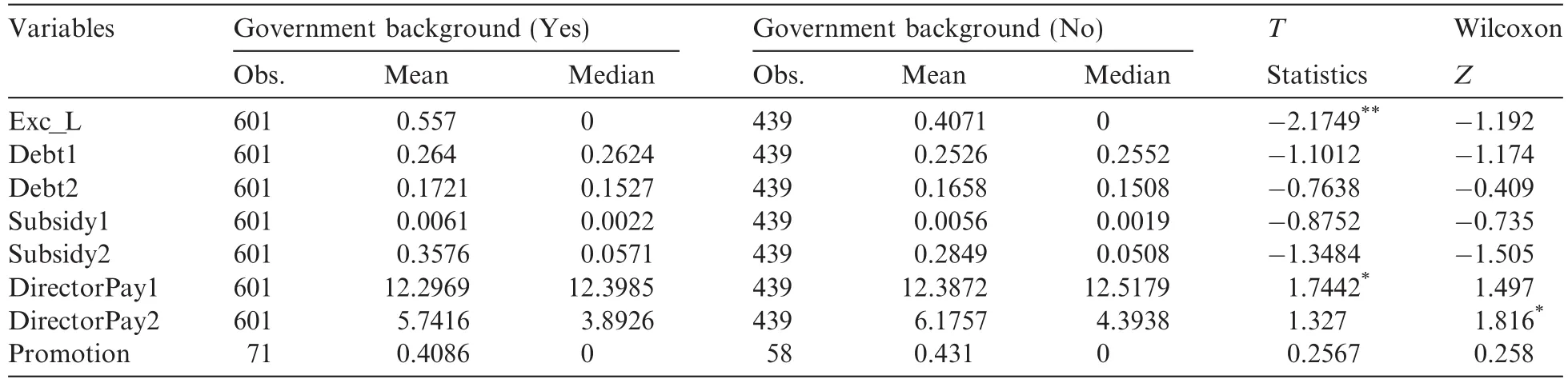

Table 3 reports the mean and median values of the dependent variables for the sub-samples distinguished by Gov_Political,as well as test statistics for differences in the mean and median values between the subsamples.We first examine the statistics of Exc_L.Consistent with hypothesis 1,we find that for firms with a political connection the mean of excess employment is 0.557 per 1 million sales,but only 0.4071 for firms whosechairman is not politically connected.The 0.15 drop in the mean is statistically significant using a two-tailed t test.Similarly,the mean pay for chairmen is 12.29 for local SOEs with chairmen of a government background. The difference between the mean values offirms with and without political connections is statistically significant.

Table 1Numbers of politically connected chairmen.

Table 2Descriptive statistics.

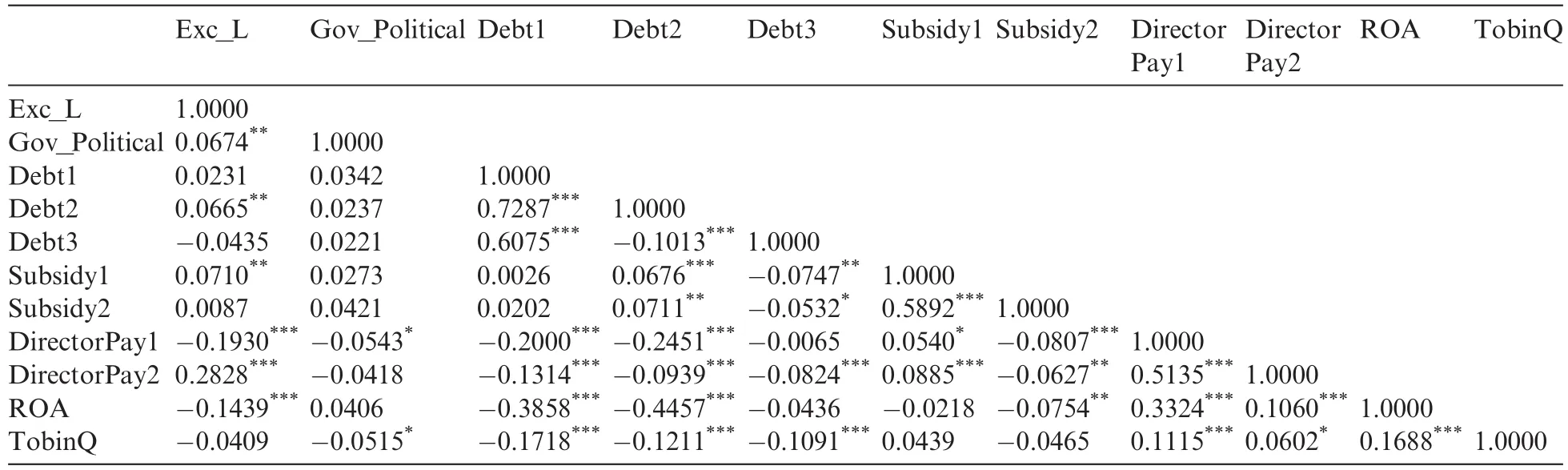

The Pearson correlation coefficients for the dependent variables used in our analysis are reported in Table 4. As expected,the correlation between Exc_L and Gov_Political is positive and significant at the 5%level.The table shows a positive correlation between Exc_L,Debt2 and Subsidy1,but a negative correlation between Exc_L,DirectorPay1 and ROA.

Table 3Mean and median tests.

Table 4Pearson correlation matrix.

5.Empirical analysis

5.1.Government background and excess employment

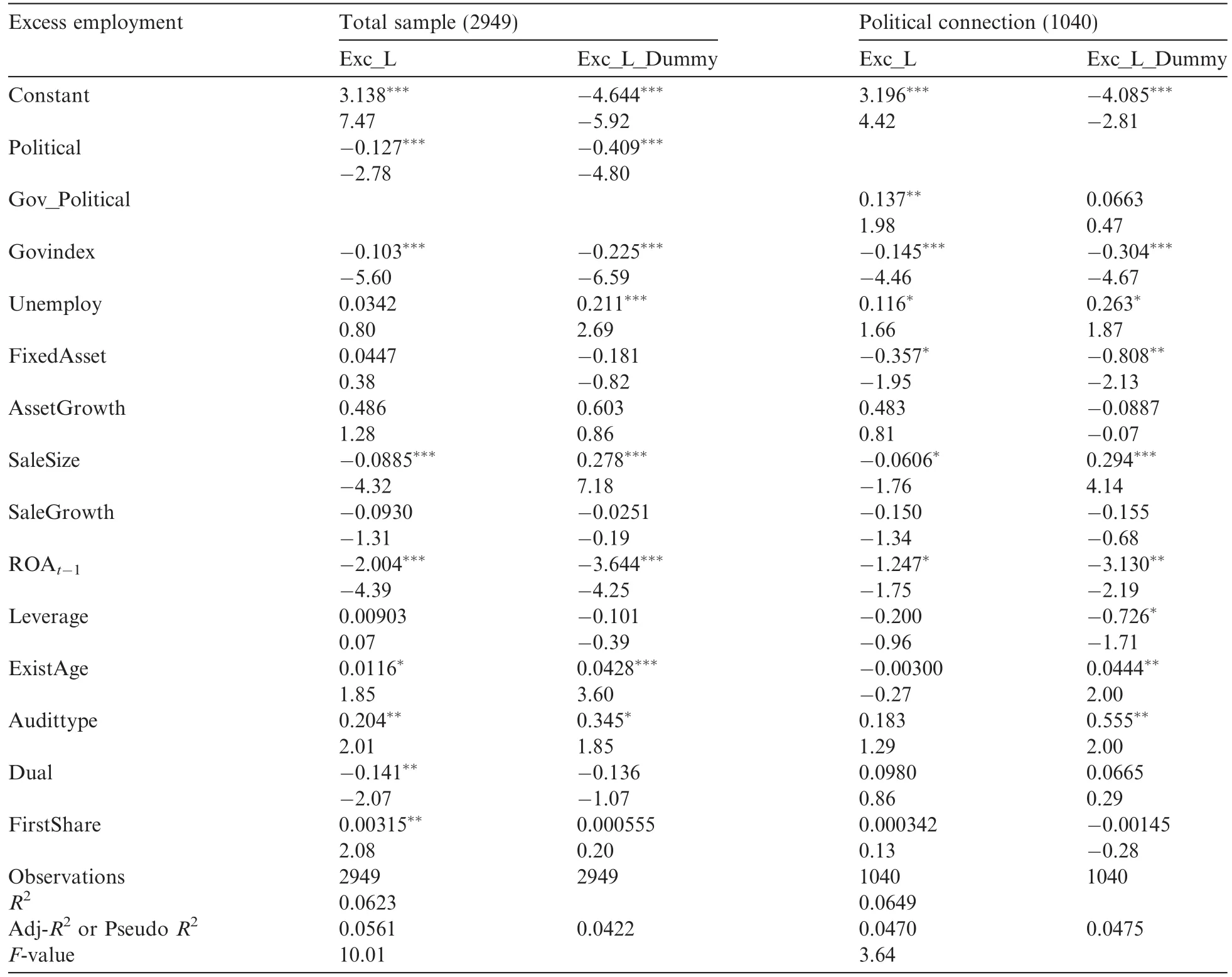

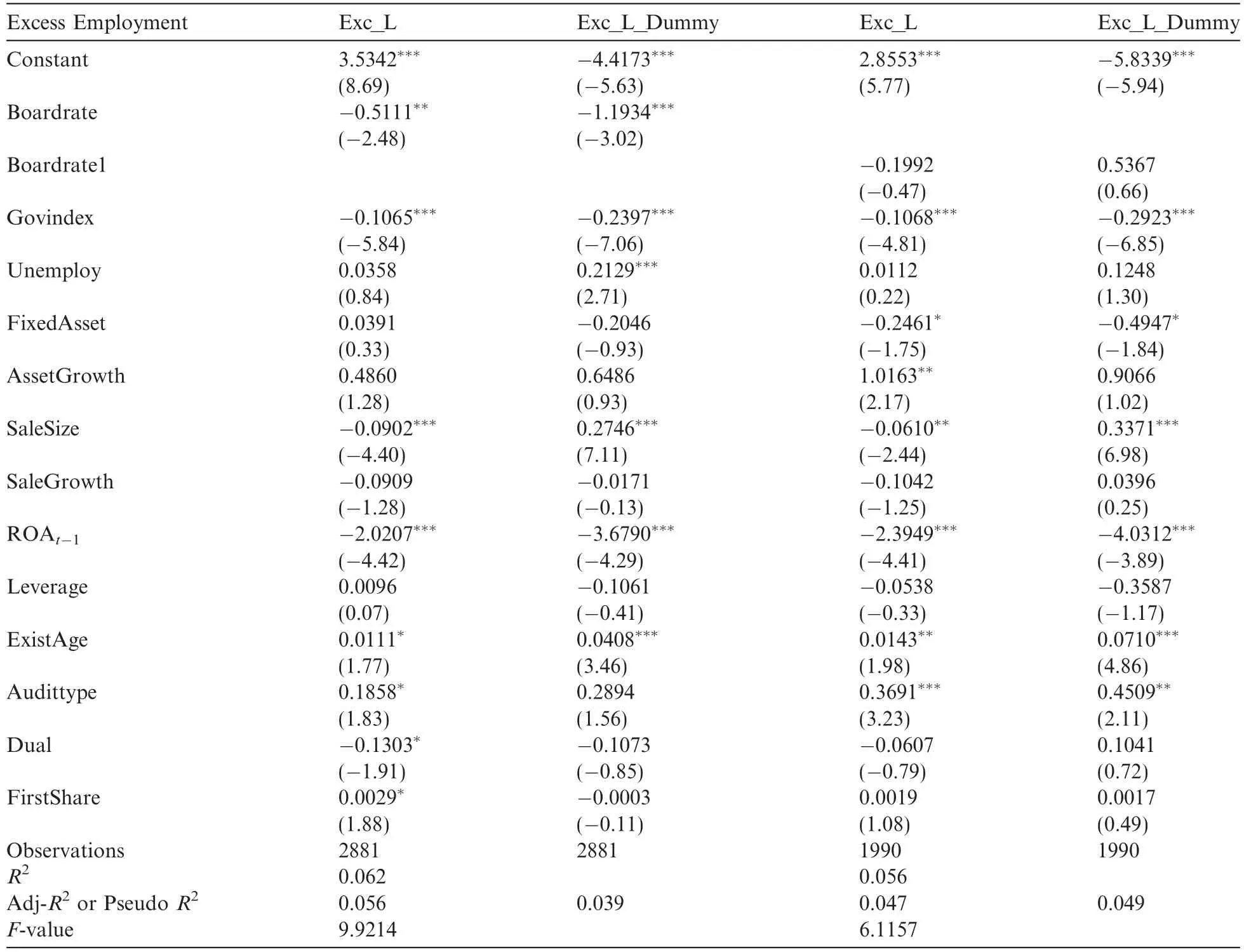

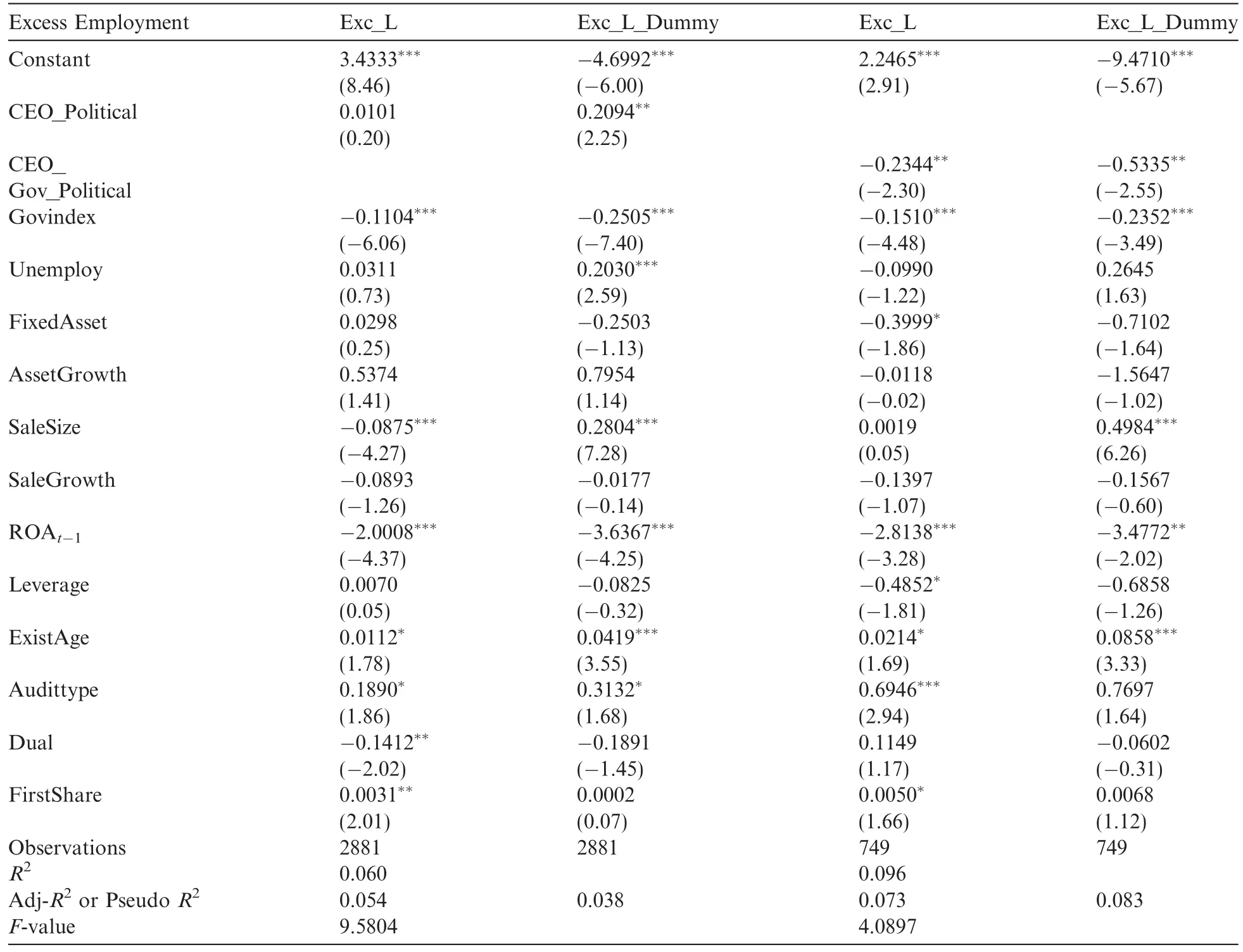

Table 5 reports the results of model(1).The variables that we want to investigate are significantly correlated(as the Pearson correlation matrix of Table 4 has shown),so we introduce the two variables,Political and Gov_Political.These variables represent political connection and government background respectively. In this regression,the dependent variable in columns 1 and 3 is Exc_L,and in columns 2 and 4 the dependent variable is Exc_L_Dummy.

Table 5Government background and excess employment.

The regression results in columns 1 and 2 of Table 5 show that political connections are negatively related to excess employment,at a significance level of 1%.This means that the general political connections can potentially help firms resist government intervention,such as pressure to employ more people.However, the further analysis in columns 3 and 4 demonstrate that having a chairman with a government background has a significant positive relationship(5%)with overstaffing in the politically connected subsample(1040 observations).This indicates that the chairman's government background is the mechanism through which the government realizes its intervention for overstaffing in local SOEs.

Table 5 also shows that local SOEs with higher government intervention index scores are less likely to sustain excess employment,as evidenced by the negative and significant coefficient on Govindex.The higher government intervention index score means less government intervention.Local SOEs in regions with weak institutions are more likely to face the problem of overstaffing,which is consistent with the findings of Shleifer and Vishny(1994)and Lin and Tan(1999).Table 5 indicates that firms located in regions with higher unemployment rates tend to hire more employees,as shown by the positive relationship between Exc_L and Unemploy.In addition,the results show that ROAt-1is significantly and negatively related to the dependent variable,which implies that the government tends to intervene to promote overstaffing in firms with poorer performance,rather than in better-performing firms.

In summary,the above results support our prediction that local SOEs are more likely to sustain excess employment when chairmen have a government background.

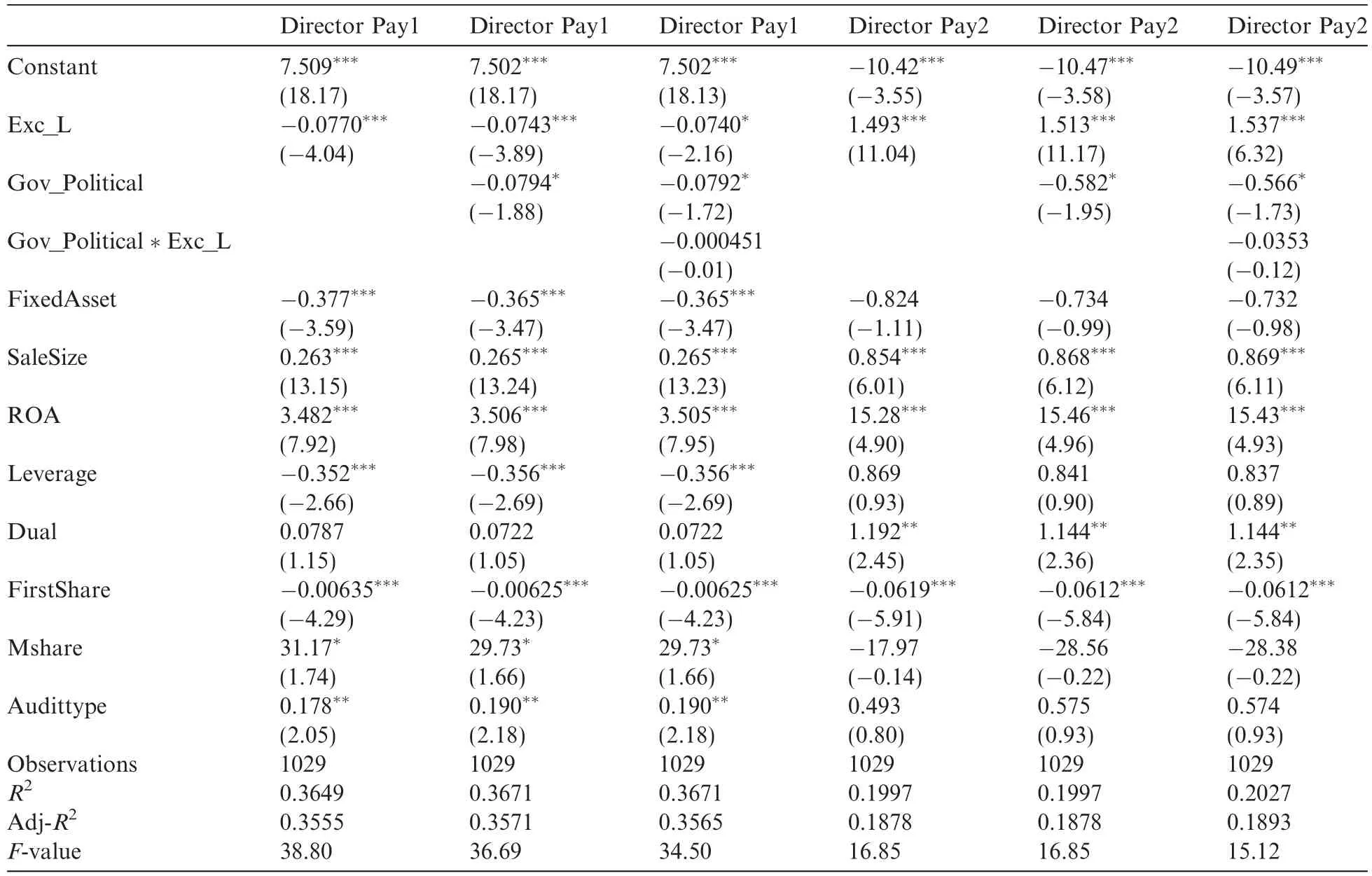

5.2.The effects of excess employment on Local SOEs-chairman level

Prior research indicates that overstaffing is negatively related to a firm's performance.The abovementioned evidence shows that local SOEs tend to sustain excess employment when their chairmen have a government background.Therefore we ask,what does the chairman gain from this behavior?As previously discussed,a chairman who promotes overstaffing may receive more money or greater promotion opportunities as compensation for incurring these negative effects on the firm.This section of our paper will examine the results of supporting excess employment for the firms'chairmen.

Table 6 presents the empirical results on the relationship between excess employment and chairmen's compensation.Contrary to our initial projections,excess employment is negatively related to chairmen's compensation at the absolute level.In other words,when a firm incurs the expenses of overstaffing,its chairman does not enjoy an increase in his/her pay.One explanation for this result may be that our measure of the chairmen's compensation is based on the compensation of the top three executives in each firm,which is not an exact measurement.However,when it comes to the relative level of chairmen's payment(as shown in columns 4, 5,and 6),the coefficients of Exc_L on DirectorPay2 are significantly positive(1%),just as we predicted in Section 2.2.2.

Table 6 also shows that in firms whose chairmen have a government background,the chairpersons themselves get much less pay than their counterparts when their companies sustain an overstaffing problem.Thechairmen's government backgrounds do not overcome the negative effects of excess employment on their compensation.

Table 6Excess employment and chairman's compensation.

InlocalSOEsthathavemoresales(greatersize)andbetteraccountingperformance,thechairmentendtogain more compensation at both the absolute and relative levels,as shown by the positive coefficients of SaleSize and ROA on DirectorPay1 and DirectorPay2.This result is consistent with prior results in this research area.

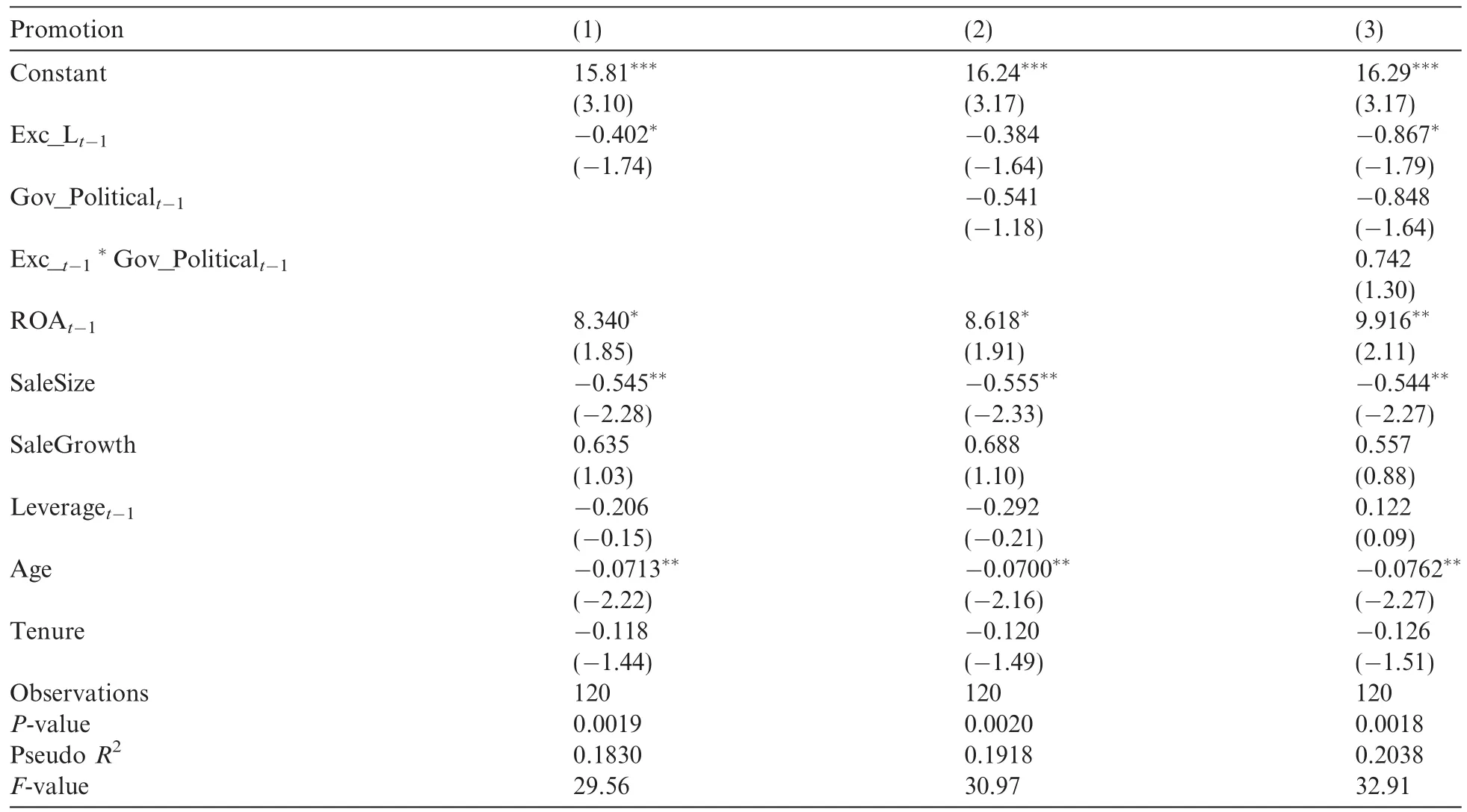

The other part of Hypothesis 2A concerns the chairmen's prospects of promotion.To study the relationship between excess employment in local SOEs and their chairmen's promotion in this model,we introduce only the firms that changed their chairmen between 2004 and 2009.Because there may be a dynamic lag in the factors influencing the turnover offirms'chairmen,we introduce the lagged variables of Exc_L,Gov_Political, ROA and Leverage.Table 7 provides the results.The results are presented in the first column.The term Exc_L,which is the primary variable of interest,has a negative coefficient that is significant at the 10%level, which shows that a policy of overstaffing tends to decrease the chairmen's promotion opportunities.This result could possibly indicate that chairmen who practice overstaffing had already been promoted by governments before they were appointed to act as the local SOEs'chairmen.Furthermore,it should be emphasized that this sample only includes 120 observations,which may affect the results.Also,the chairmen's age is negatively related to promotion opportunities,which means that chairmen have less opportunity for promotion as they grow older.This finding is also consistent with the promotion trend for younger managers in China.

In the second column of Table 7,we add Gov_Political and find that there is no significant relationship between the chairmen's promotions and the firms'levels of overstaffing,although the sign of the coefficient is negative.

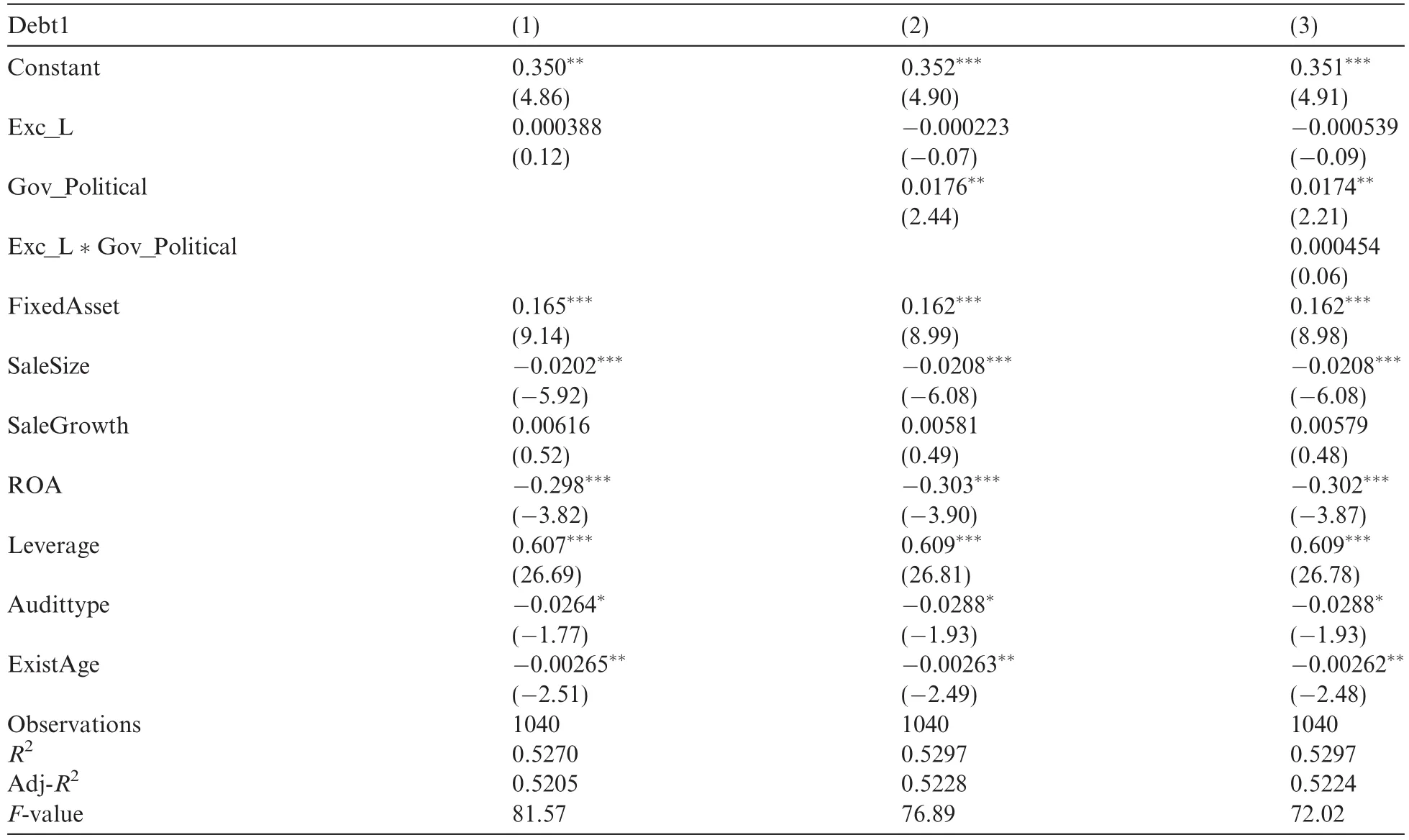

5.3.The effects of excess employment on local SOEs-firm level

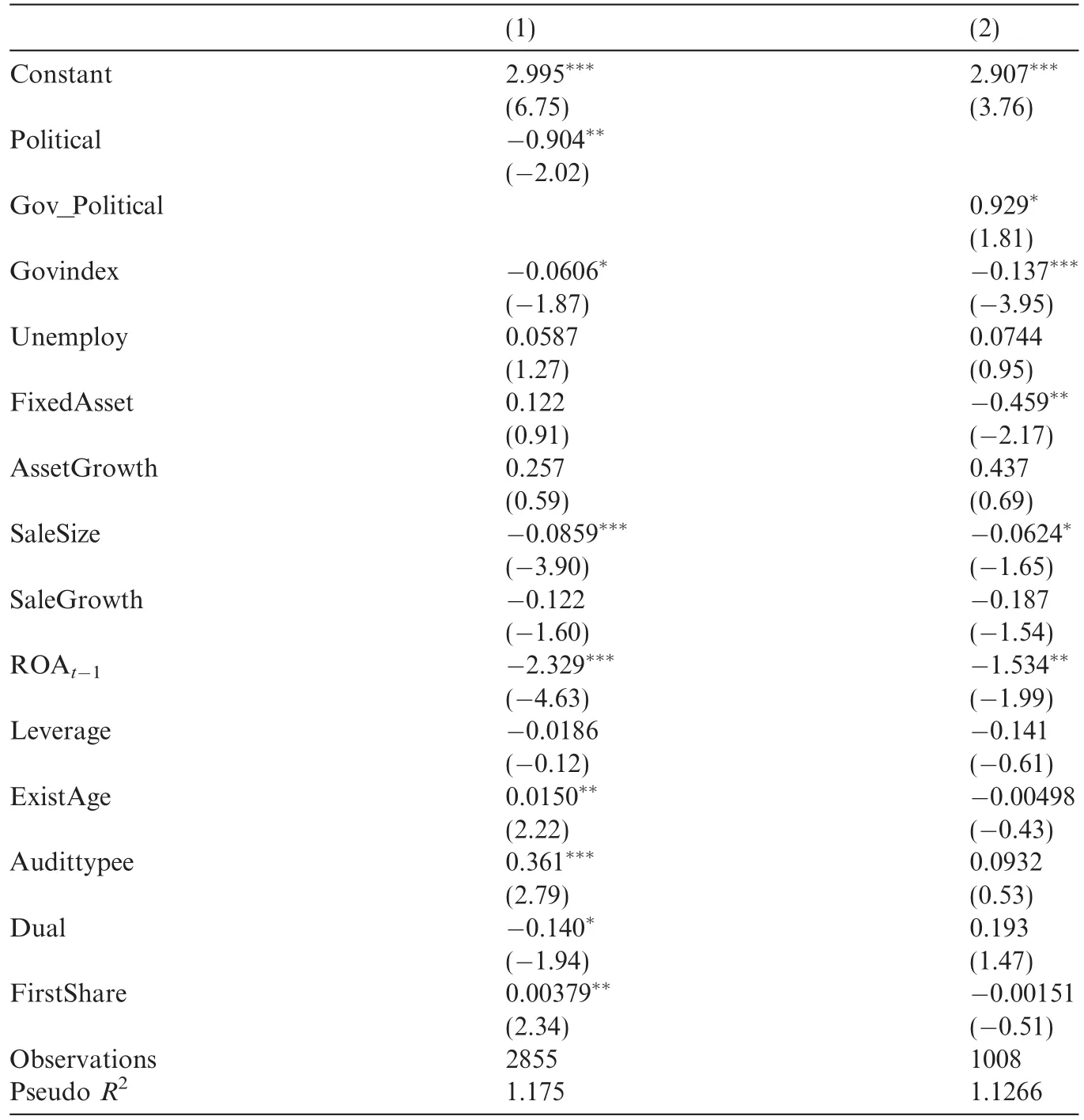

Next we test Hypothesis 2B,to investigate whether local SOEs whose chairmen have government backgrounds receive more bank loans or government grants.In Table 8,we run the regressions to test therelationship between debt maturity and excess employment.The results shown in the table indicate that the firms'levels of overstaffing are not significantly related to the amount of long-term debt the firms receive from banks.However,consistent with the findings of Yu and Pan(2008),politically connected firms have greater access to debt than firms without political connections.

Table 7Excess employment and chairman's promotion.

In addition,we use another two variables,Debt 2 and Debt 3,to examine this hypothesis.The results,given in Table 9,are similar to those shown in Table 8.

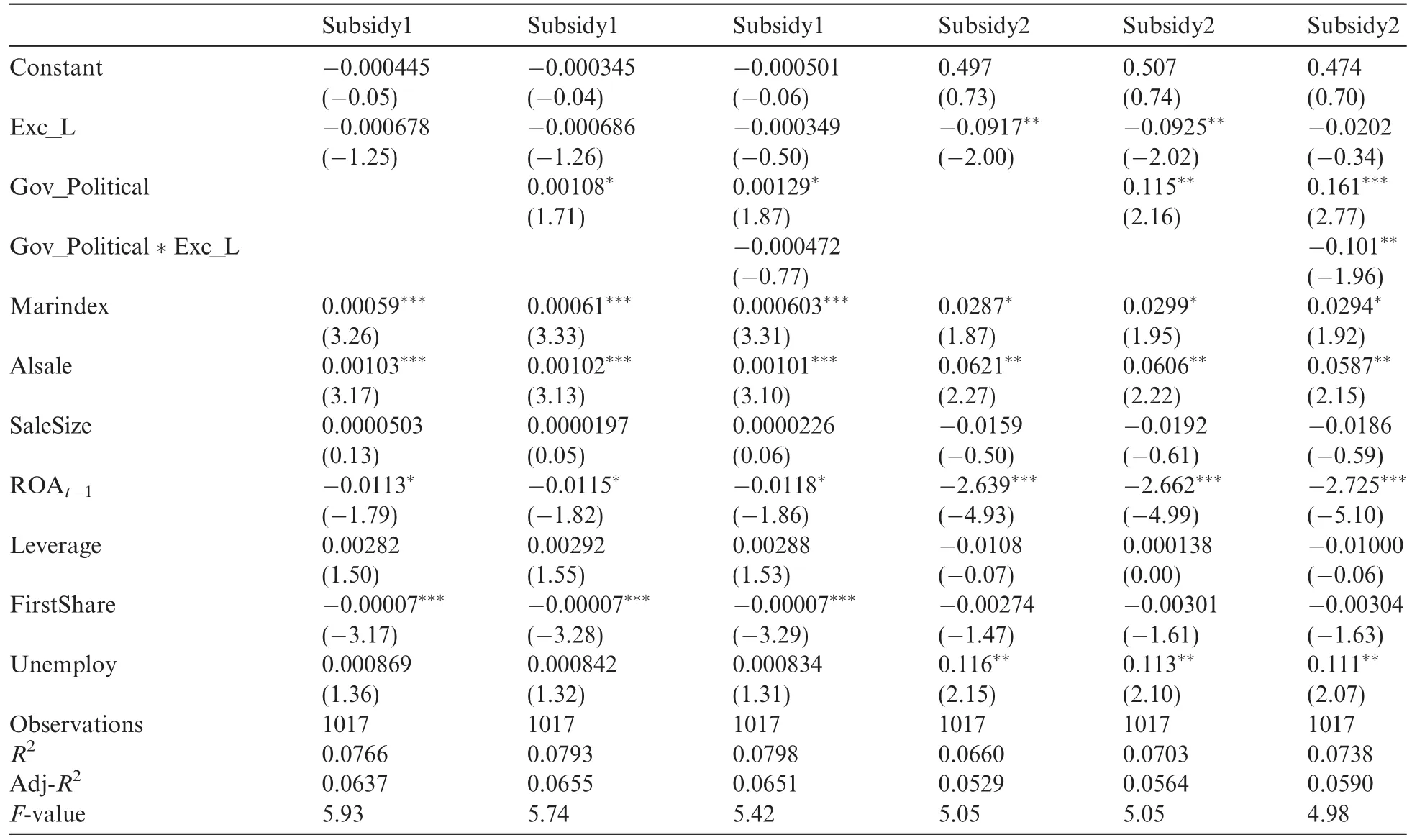

We perform OLS regressions to identify government grants that could be influenced by the firms'excess employment and Table 9 shows the regression results.We find that excess employment by firms is not related to the government subsidies those firms receive.The government background variable(Gov_Political)is positively related to government subsidies,as expected,and the relationship is statistically signi ficant.We also find that the regional marketization level(Marindex)is significantly and positively related to government subsidies.This finding indicates that when the local economy develops well,the firms in these regions are more likely to receive government subsidies from the local government.Although the firm's overstaffing scale is irrelevant to the level of government subsidies,the actual number of employees(Alsale)is statistically significant and positively related to government grants.This positive relationship may suggest that firms with more employees attract more government subsidies,because they help the government with the unemployment rate.

Table 8Excess employment and local SOEs'debt financing.

5.4.Additional analysis

The above tests show that governments intervene into local SOEs'employment decisions by nominating chairmen who have government backgrounds.The tests also show the effects of overstaffing problems on firms and on their chairmen.However,we also need to know how these factors influence the firms'performance.To provide insight into whether and/or how excess employment,debt financing and government subsidies influence a firm's labor costs or accounting performance,we conduct further analysis in this section.

Table 9Excess employment and government subsidies.

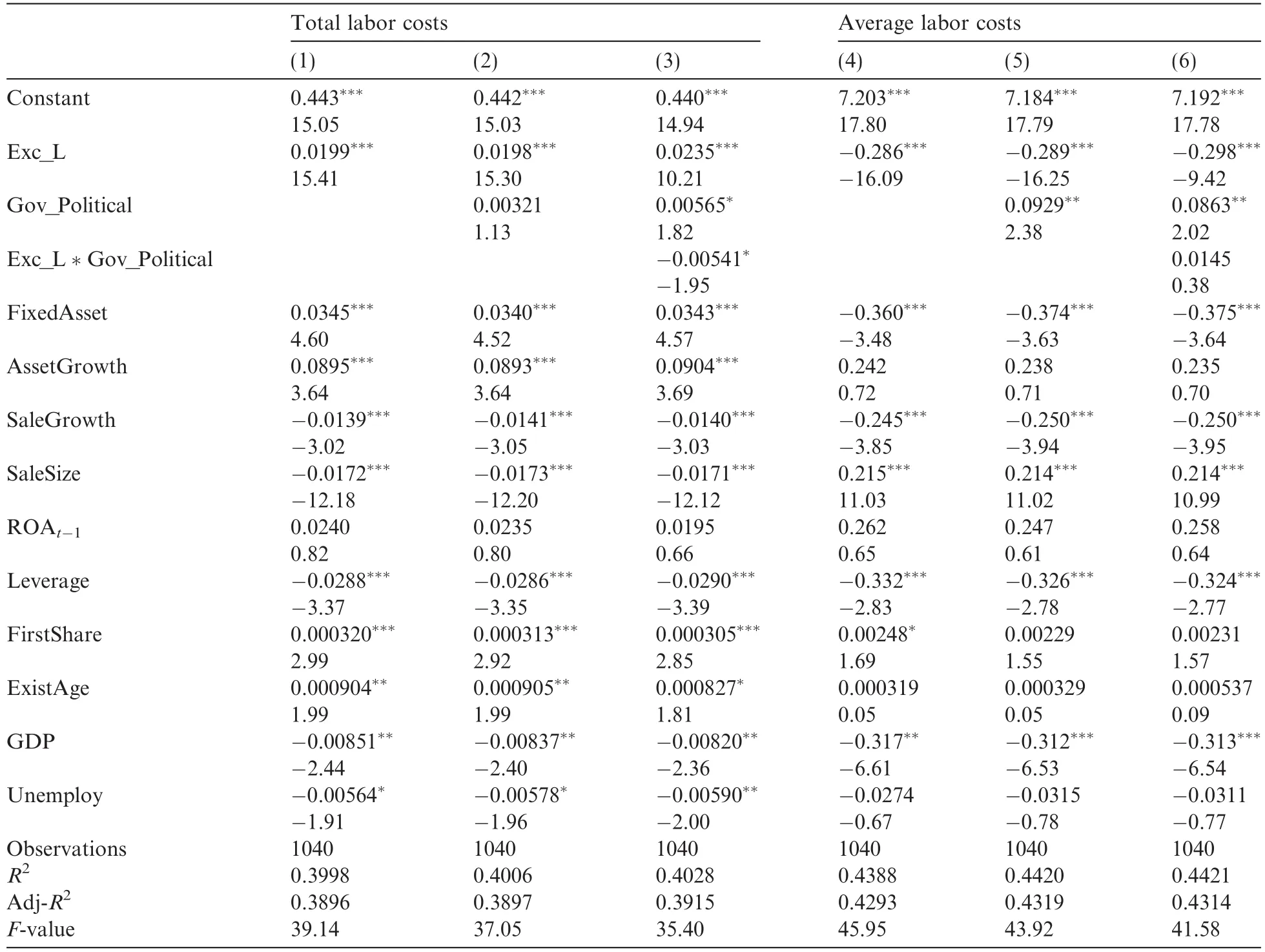

First,we perform regressions to examine the factors that influence the companies'labor costs.The dependent variable is a continuous variable and we introduce two measurements to proxy for this.The first measurement is Total Labor Cost,which is calculated as“cash paid to and on behalf of employees”from the cash-flow statement divided by total sales.The other measurement is Average Labor Cost,which is calculated as the logarithm of“cash paid to and on behalf of employees”divided by the total number of employees.In these regressions,we exclude the compensation and the number of employees who are related to their firm's chairman.The most important independent variable of interest is the firm's excess employment(Exc_L).The control variables(as defined in Appendix A)include the regional macroeconomic variables of GDP per capita and unemployment rate,and a number offirm-level variables including the firms'percentage offixed assets in relation to total assets,asset growth,sales growth,log of total sales,ROAt-1,leverage percentage of ownership by the largest shareholder and age of the firm.Year and industry dummies are also included in the regression but not reported.

Table 10 reports the regression results.Consistent with the findings of Zeng and Chen(2006),the firms' scale of overstaffing is significantly and positively related to total labor costs,and negatively related to the average labor costs.These results confirm that excess employment is a typical result of the government's“grabbing hand,”which does harm to the firms'operations.Although excess employment increases the firms' total labor costs,it also decreases the average salaries that employees receive.

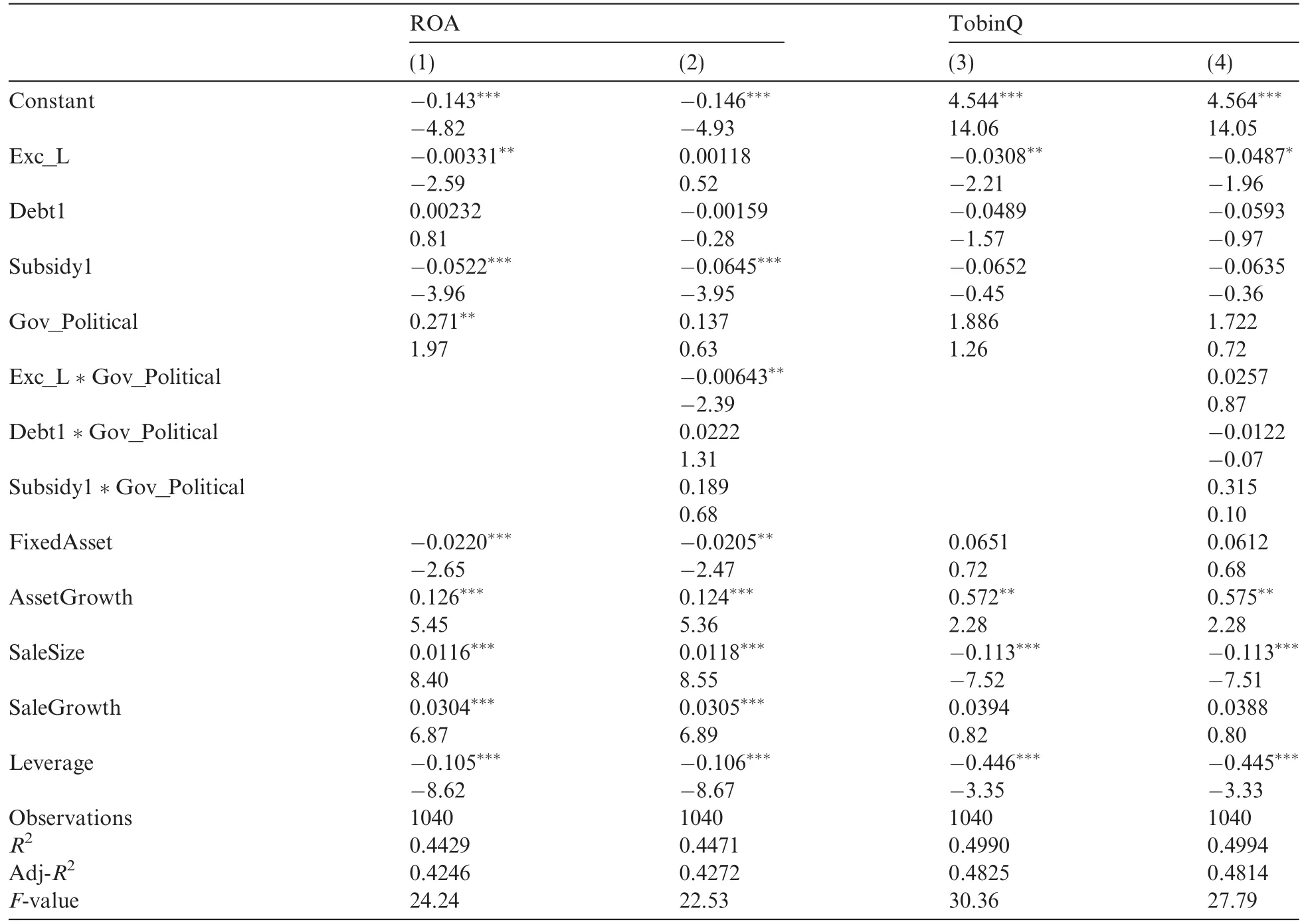

Table 11 reports the results concerning the relationships between the state owned firms'excess employment, debt,subsidies and accounting performance.We use ROA and TobinQ to measure the firms'accounting performance.The independent variables include Exc_L,Debt1,Subsidy1 and several firm-level variables.

The results in Table 11 are as follows.(1)Consistent with the findings of Xu et al.(2005)and Xue and Bai (2008),a firm's excess employment decreases its accounting performance,as shown by the significant negative coefficients on Exc_L.(2)Debt financing is negatively related to firm performance,but the relationship is notstatistically significant.The reason may be that debt financing,as a rent-seeking process,does harm for both the firm and the government,and therefore hinders firm performance.(3)Having chairmen with government backgrounds is positively related to ROA and TobinQ,but not to a significant degree.To summarize,the negative effects of the government's“grabbing hand”are obvious and the“helping hand”effect is not so obvious. In both cases,however,government intervention does harm to firms.

Table 10Tests of labor costs.

5.5.Robustness tests

One concern with our analysis is the potential for reverse causality.Specifically,it is possible that the government assigns candidates to firms with excess employment.The government maintains the ultimate authority regarding appointments of CEOs or chairmen in SOEs and may do so according to its own priorities.In attempting to mitigate this endogeneity issue,we perform the following three tests.

5.5.1.Redefining political connections

In the previous sections of this paper,we only focus on the political connections of SOE chairmen.However,the boards of these firms are often responsible for overseeing managers,especially CEOs,and board members may also have political connections.Consequently,to account for this type of political connection,we collect information on board members and rate the members who have political connections as a proxy for political connections according to the following variables.Boardrate=the number of board directors with political connections/board size.Boardrate1=the number of board directors with industry-related government background/board size.Furthermore,instead of just focusing on the chairmen's political backgrounds, we also examine the CEO's political backgrounds,and the effect these connections have on firm employment levels.

The results are tabulated in Table 12.The regression results in columns 1 and 2 show that the rate of political connections on boards is negatively related to excess employment,which means that the more politically connected board members a firm has,the lower its level of excess employment.However,when it comes to columns 3 and 4,the results show no significant positive relationship between the proportion of board directors with industry-related political backgrounds and excess employment in their firms.

Table 13 reports the results from the examination of the CEOs'political connections.We find that there is no significant relationship between the CEOs political connections and overstaffing in their firms.However, the subsample shows that the CEOs'industry-related political backgrounds are negatively related to excess employment(statistically significant),which is a different result from that found in Table 5.The results in Tables 12 and 13 confirm that appointing politically connected board directors or CEOs is not the mechanism for the government to solve the employment problem.Redefining political connectedness according to board member or CEO connections cannot substitute for a focus on the chairmen's political connections in explaining overemployment.

Table 11Tests of the government's“Grabbing Hand”and“Helping Hand”.

Table 12Board political connections and excess employment.

5.5.2.Excess employment around chairman turnover

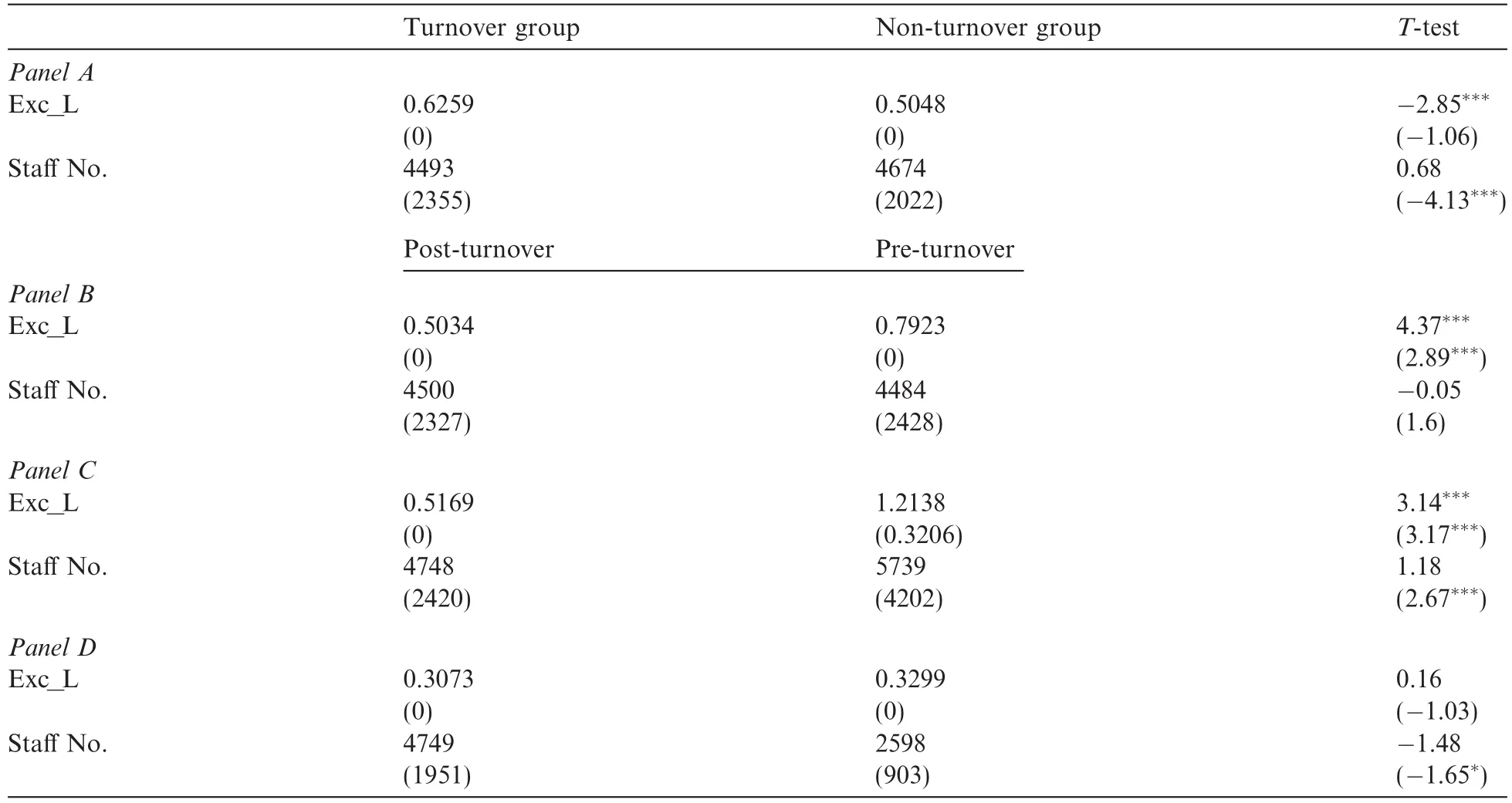

To examine the reverse causality problem more deeply,we identify exogenous changes in the firms'chairmen that are not caused by policy reasons.To do this,we divide the total sample into two groups,according to whether the firms have experienced a chairman turnover during the 2004-2009 period.Some 343 cases of chairman turnover appear among the 1500 firm observations.In Table 14,we present summary statistics comparing the employment situations of the turnover and the non-turnover groups.In addition,we test the differences before and after a chairman turnover for the turnover group.The cross-sectional mean(median) values of the firms'employment situations are reported,as well as the t-statistic and the Wilcoxon values of the difference tests.

To compare the employment situations of the two groups,panel A shows that the level of excess employment(t=-2.85,1%)and the absolute number of employees(Z=-4.13,1%)in the turnover group are significantly higher than in the non-turnover group.Panel B shows the results of employment differences before and after the chairman turnovers in the turnover group.We can see that the firms'excess employment before the chairman turnovers is significantly lower than it is after the turnovers.This is consistent with the previously demonstrated negative relationship between political connections and excess employment.

We also identify cases among local SOEs in which the previous chairmen were not politically connected and the new chairmen who replaced them had political connections.Panel C of Table 14 shows that both theoverstaffing scale and the staf fnumbers are statistically and significantly lower after the chairman turnovers. Panel D focuses on the chairmen's government backgrounds and shows no significant difference in employment levels before or after turnover in this subsample.

Similarly,we test how employment levels change when a chairman with a political background is replaced by a new chairman with such a background.The results(not reported)show no significant difference for employment levels for this type of turnover.

Table 13CEO political background and excess employment.

5.5.3.Determinants of chairmen's political ties

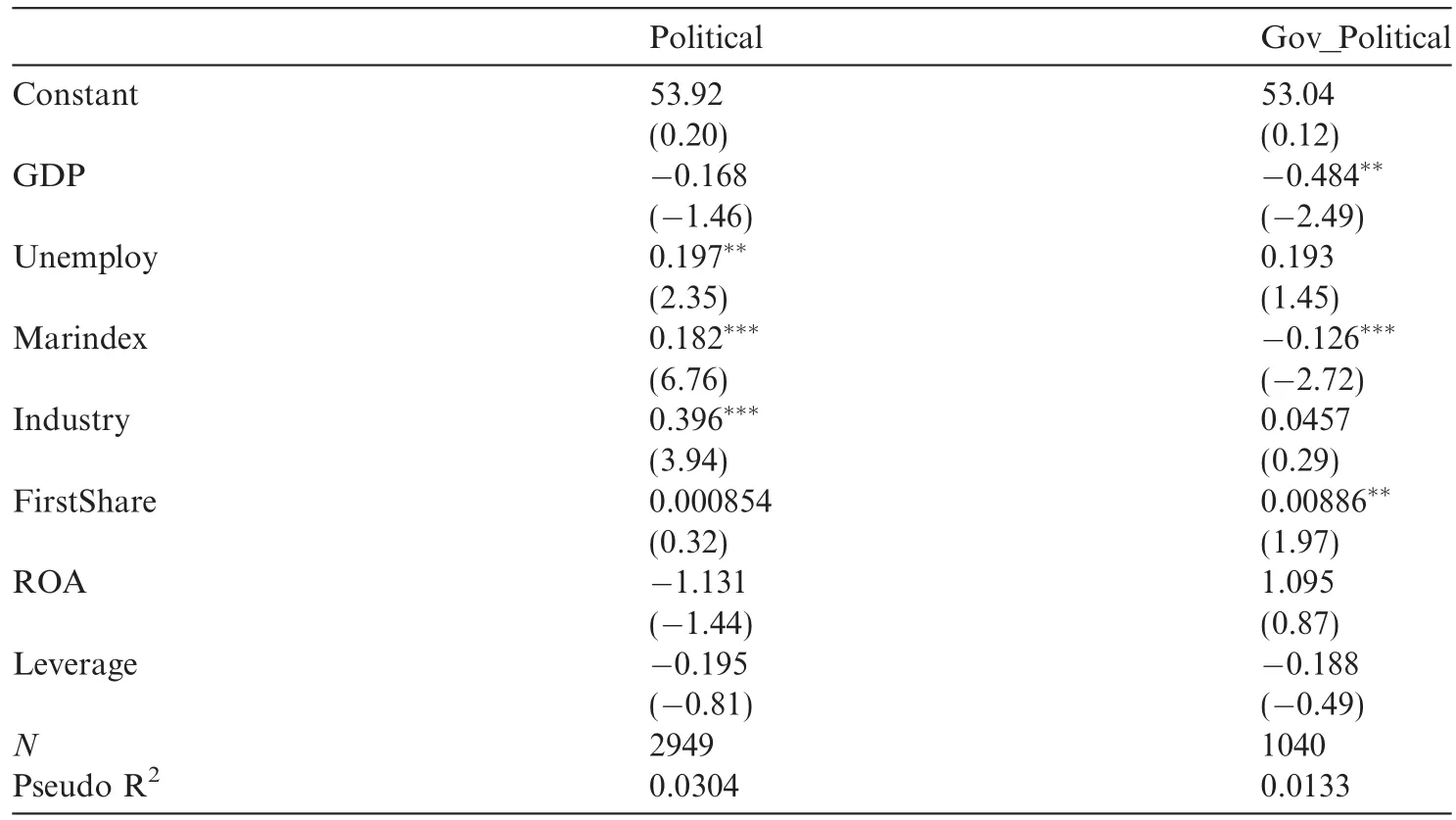

In further attempting to mitigate the endogeneity issue,we use a two-stage approach.In the first stage we perform logistic regressions to identify factors that influence the election of politically connected chairmen. According to Fan et al.(2007)and Yu and Pan(2008),we control for the following variables.The dependent variable is a dummy variable,equal to 1 if the chairman is a current or ex-government bureaucrat,and 0 otherwise.The independent variables,as defined in Appendix A,include regional macroeconomic factors of per capita GDP,unemployment rate and process of marketization,and a few industry-and firm-level variables, including a regulated industry dummy,the ownership percentage of the largest shareholder,ROA and leverage.Year dummies are included in the regression but not reported.

Table 14Univariate tests of employment around chairman turnover.

Table 15 reports the regression results.GDP is negatively related and the local unemployment rate is significantly and positively related to the appointment of politically connected chairmen.These regression results suggest that when local governments are facing the challenge of meeting economic and employment targets, they have an incentive to appoint politically connected chairmen.We also find that a local SOE is more likelyto get a politically connected chairman if the firm is in a regulated industry.This finding may indicate that firms in regulated industries may need more political connections to help them succeed.

Table 15Test of the determinants of chairmen's political ties.

Inthesecondstageregression,weusethemodelfromTable5butincludethe first-stagemodel'spredictionsof the probability of politically connected chairmen.The results of this two-stage approach,as shown in Table 16, remain qualitatively similar to previously reported findings.The predicted relationship between politically connected chairmen and excess employment is negative and statistically signi ficant(at 5%).As predicted,having a chairman with a government background is positively and significantly(10%)related to excess employment.

Table 16Regression results of two-stage approach.

6.Conclusions and limitations

This paper explores the influence of government interventions on listed local Chinese SOEs and specifically investigates the affects of interventions to nominate politically connected people as chairmen in SOEs.We study the role of chairmen with government backgrounds in shaping firms'employment decisions and the effects of overstaffing on both the chairmen's income and the firms'operations.As evidence,we use comprehensive financial and accounting data from 2004 to 2009,together with detailed information on SOE chairmen and macroeconomic data for local regions in China.After studying the relationship between excess employment and the chairmen's government backgrounds,we examine the consequences of excess employment on local SOEs.We find evidence supporting the argument that appointing chairmen with government backgrounds is the mechanism through which the government intervenes in these firms'employment decisions.

First,we find that local SOEs whose chairmen have only general political connections are less likely to hire extra staf fthan chairmen with a professional background in government.This finding implies that different kinds of political relationships play different roles.Second,contrary to our prediction,excess hiring by firms does not bring much bene fit to the chairmen personally,but does provide firms with better access to debt financing and government subsidies.This finding indicates that governments tend to compensate firms for helping to reduce the social burden of unemployment.Additional analysis indicates that the negative effects of the government's“grabbing hand”are obvious,and the positive effects of its“helping hand”are very weak. This indicates that government intervention in firms disturbs their normal operations and reduces the efficiency of resource distribution.

This analysis has very strong policy implications.We demonstrate that appointing chairmen is an indirect way for the government to intervene in local SOEs.Also,the support that governments offer firms in return for overstaffing does not significantly improve the firms'long-term performance.This finding suggests that the government should reduce interference in local SOEs and take more effective measures to improve the positive value of government subsidies.

This study is subject to the following limitations.First,there is a possibility that SOEs with low efficiency or excessive labor forces are more likely to hire ex-government bureaucrats as chairmen.Our two-stage approach for mitigating this endogeneity issue continues to provide support for the relationship between excess employment and political connections,but we cannot completely rule out this endogeneity concern.Second,the firms selected in our sample are all local SOEs.This may cause a problem of sample selection and limit the generalizability of the results.Prior studies demonstrate that firms with different kinds of ownership tend to operate in different ways.Therefore,future research should examine central government SOEs and private firms in comparison with the situation of local SOEs.

Appendix A

See Table A1.

Table A1Variable definitions.

Bennedsen,Morten,2000.Political ownership.Journal of Public Economics 76(3),559-581.

Bertrand,M.,Kramarz,F.,Schoar,A.,Thesmar,D.,2006.Politicians,Firms and the Political Business Cycle:Evidence from France. Working Paper.University of Chicago.

Boycko,M.,Shleifer,A.,Vishny,R.W.,1996.A theory of privatisation.The Economic Journal 106(435),309-319.

Brickley,J.A.,Coles,J.,Linck,J.S.,1999.What happens to CEOs after they retire?New evidence on career concerns,horizon problems, and CEO incentives.Journal of Financial Economics 52(3),341-377.

Cao,J.,Lemmon,Michael,Pan,Xiaofei,Qian,Meijun,Tian,Gary,2012.Political Promotion,CEO Incentives,and the Relationship between Pay and Performance.Working Paper.SSRN.

Chen,Donghua,2003.A study and analysis on local government,corporate government:empirical evidence from subsidy in china. Economic Research Journal 9,15-21.

Chen,C.,Li,Z.,Su,X.,2005.Rent Seeking Incentives,Political Connections and Organization Structure:Empirical Evidence from Listed Family Firms in China.Working Paper.The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Chen,G.,Firth,M.,Xin,Y.,Xu,L.,2008.Control transfers,privatization,and corporate performance:efficiency gains in China's listed companies.Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 43(1),161-190.

Chung,Wai-Keung,Hamilton,Gary G.,2002.Social logia as business logic:Guanxi,trustworthiness,and the embeddedness of Chinese business practices.In:Appelbaum,Richard P.,Felstiner,William L.F.(Eds.),Rules and Networks.Hart Publishing,Oxford.

Claessens,Stijn,Feijen,Erik,Laeven,Luc,2008.Political Connections and preferential access to finance:the role of campaign contributions.Journal of Financial Economics 88(3),554-580.

Dewenter,K.L.,Malatesta,Paul H.,2001.State-owned and privately owned firms:an empirical analysis of profitability,lever age,and labor intensity.The American Economic Association 49(1),320-334.

Dong,X.Y.,Putterman,Louis,2001.On the emergence of labour redundancy in China's state industry:findings from a 1980-1994 data panel.Comparative Economic Studies 2,111-128.

Dong,X.Y.,Putterman,Louis,2003.Soft budget constraints,social burdens,and labor redundancy in China's state industry.Journal of Comparative Economics 31,110-133.

Faccio,M.,2006.Politically connected firms.American Economic Review 96(1),369-386.

Faccio,Mara,McConnell,John J.,Masulis,Ronald W.,2006.Political connections and corporate bailouts.Journal of Finance 61(6), 2597-2635.

Fan,J.P.H.,Wong,T.J.,Zhang,T.Y.,2007.Politically-connected CEOs,corporate governance and post-IPO performance of China's partially privatized firms.Journal of Financial Economics 84(2),330-357.

Fan,Gang,Wang,Xiaolu,Zhu,Hengpeng,2010.NERI INDEX of Marketization of China's Provinces 2009 Report.Economic Science Press.

Fisman,R.,2001.Estimating the value of political connections.American Economic Review 91(4),1095-1102.

Gillan,S.L.,Hartzell,J.C.,Parrino,R.,2009.Explicit versus implicit contracts:evidence from CEO employment agreements.Journal of Finance 64(4),1629-1655.

Johnson,S.,Mitton,T.,2003.Cronyism and capital controls:evidence from Malaysia.Journal of Financial Economics 67(2),351-382.

Li,David D.,1998.Changing incentives of Chinese bureaucracy.The American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 88(2),393-397.

Li,David D.,Liang,Minsong,1998.Causes of the soft budget constraint:evidence on three explanations.Journal of Comparative Economics 26,104-116.

Li,Hongbin,Zhou,Li-an,2005.Political turnover and economic performance:the incentive role of personnel control in China.Journal of Public Economics 89,1743-1762.

Li,H.,Meng,L.,Zhang,J.,2006.Why do entrepreneurs enter politics.Economic Inquiry 44(3),559-578.

Li,H.,Meng,L.,Wang,Q.,Zhou,L.,2008.Political connections,financing and firm performance:evidence from chinese private entrepreneurs.Journal of Development Economics 87(2),283-299.

Lin,J.Y.,Tan,G.,1999.Policy burdens,accountability,and the soft budget constraint.American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 89(2),426-431.

Liu,Huilong,Zhang,Min,Wang,Yaping,Wu,Liansheng,2010.Political connections,compensation incentives,and employee allocation efficiency.Economic Research Journal 9,109-121.

Luo,Donglun,Zhen,Mingli,2008.Privately control,political relationship and financing constraint:an empirical evidence of private enterprises listed in China.Journal of Financial Research 12,164-178.

Michelson,Ethan,2007.Climbing the dispute Pagoda:grievances and appeals to the official justice system in Rural China.American Sociological Review 72(3),459-485.

Qian,Y.,1995.Reforming corporate governance and finance in China.In:Aoki,M.,Kim,H.(Eds.),Corporate Governance in Transitional Economies.World Bank,Washington,DC.

Roberts,B.E.,1990.A dead senator tells no lies:seniority and the distribution of federal benefits.American Journal of Political Science 34, 31-58.

Sappington,D.,Stiglitz,J.,1987.Privatization,information and incentives.Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 6(4),567-582.

Shleifer,A.,Vishny,R.,1994.Politicians and firms.Quarterly Journal of Economics 109,995-1025.

Siegel,Jordan I.,2007.Contingent political capital and international alliances:evidence from South Korea.Administrative Science Quarterly 52(4),621-666.

Tenev,S.,Zhang,C.,Brefort,L.,2002.Corporate Governance and Enterprise Reform in China:Building the Institutions of Modern Markets.Work Bank and International Finance Corporation.

Wang,Kemin,Wang,Zhichao,2007.Executive control power,compensation and earnings management.Management World 7,111-119.

Wu,Wenfeng,Wu,Chongfeng,Rui,Meng,2009.CEO's government background of chinese listed companies and tax preferences. Management World 3,34-42.

Xu,L.C.,Zhu,Tian,Lin,Yimin,2005.Politician control,agency problems and ownership reform:evidence from China.Economics of Transition 13(1),1-24.

Xue,Yunkui,Bai,Yunxia,2008.State ownership,redundant employees and firm performance.Management World 10,96-105.

Yu,Minggui,Pan,Hongbo,2008.The relationship between politics,institutional environments and private enterprises'access to bank loans.Management World 8,9-21.

Yu,Minggui,Hui,Yafu,Pan,Hongbo,2010.Political connections,rent seeking,and the fiscal subsidy efficiency of local governments. Economic Research Journal 3,65-77.

Yuan,Q.,2011.Public Governance,Political Connectedness,and CEO Turnover:Evidence from Chinese State-Owned Enterprises. Working Paper.SSRN.

Zeng,Qingsheng,Chen,Xinyuan,2006.State stockholder,excessive employment and labor cost.Economic Research Journal 5,74-86.

Zhang,Weiying,1999.The Theory of the Firm and the Reform of Chinese Enterprises.Peking University Press.

28 June 2012

*Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:wangxiongyuan72@163.com(W.Xiongyuan),sunny05fly@yahoo.com.cn(W.Shan).

Government background

Excess employment

Government intervention