Epidemiologic survey and analysis of mild cognitive impairment amongst community senior citizens of Changsha City

Xueqing Zhang, Hui Zeng

Epidemiologic survey and analysis of mild cognitive impairment amongst community senior citizens of Changsha City

Xueqing Zhang1, Hui Zeng2

Objective:The purpose of the current study was to conduct a mild cognitive impairment (MCI) prevalence survey among the community senior citizens of Changsha City and analyze possible relevant factors so as to perform early screening and intervention for MCI patients, and delay or prevent MCI from developing into Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Methods:Between April and September 2012, a total of 1764 community senior citizens in Changsha City were selected through multi-stage and random cluster sampling as study subjects. The following tables were used during the investigation to perform preliminary MCI screening for the subjects of this study: a general information survey; Mini-Mental State examination (MMSe); Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA); Beijing version; global Deteriorate Scale (gDS); Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale; and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale. Then, neurology specialists made diagnoses according to the actual status of subjects, survey findings, and clinical MCI diagnostic standards. The prevalence of MCI was calculated and the rates concerning senior citizens with different demographic characteristics were compared. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze relevant factors that led to MCI, and comparing findings with those of other cities was conducted.

Results:The MCI prevalence among senior citizens in Changsha City was 16.27% (287/1 764). The MCI prevalence increased with age [for the 60, 70, and 80 age groups, the prevalence was 9.79% (84/858), 20.14% (149/740), and 32.53% (54/166), respectively,P<0.05]. The more education received, the less the likelihood of developing MCI [the prevalence of illiteracy, those who went to primary school, junior high school, senior high school, or technical secondary school, college, and undergraduates and above was 32.10% (26/81), 18.40% (90/489), 13.97% (70/501), 15.29% (61/399), 14.39% (19/132), and 12.96% (21/162), respectively,P<0.05]. Blue-collar workers’ chances of developing MCI was higher than white-collar workers [19.12% (187/978) and 12.72% (100/786), respectively,P<0.05]. Living alone increased the likelihood of developing MCI than not living alone [21.59% (65/301) and 15.17% (222/1 463),P<0.05]. The logistic regression analysis showed that age, educational background, and marital status were in the regression (P<0.05). The MCI prevalence of Changsha did not differ from that Portugal, Singapore, Beijing, and Urumchi (P>0.05), but lower than Shanghai [35.78% (161/450)] and higher than Chengdu [2.35% (92/3 910)] (P<0.05).

Conclusion:The prevalence of MCI among the community senior citizens of Changsha City is highly related to factors like age, educational background, and marital status. Prevention against these high-risk factors shall be carried out to delay cognitive decline for senior citizens.

Senior citizens, Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), MMSe, MoCA, gDS, CDR, ADL, Neurology, Changsha City

Introduction

The aging population has become a global public health and social problem. China has the largest aging population worldwide (100 million) [1]. The population with advanced age >80 and >90 years are growing by 5.4% and 7.1%, respectively [2]. By 2012, the population >60 years of age will have reached 194 million, while the population >80 years of age will have reached 22.73 million [3]. Along with aging and old-aging, the prevalence Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is on the rise every year. Domestic research indicates that the prevalence of AD for senior citizens >65 years of age is 3%~5%; this rate increases to 20% for people >80 years of age and 50% for those >90 years of age [4]. Overseas studies show that the prevalence of AD increases rapidly with aging. The prevalence is <1% for people 60~69 years of age and this rate increases to 39% for people 90~95 years of age. Thus, the prevalence doubles along with each 5-year increment increase in age [5].

AD has a great influence on the health and quality of life of senior citizens [6]; AD is accompanied by economic, caring [7], and psychological [8] burden to the people who care for senior citizens; however, there is still no effective cure or intervention for this kind of disease. As a high-risk group, patients with MCI have attracted great attention from many scholars [9]. Liu-Ambrose et al. [10] research shows that 8%~25% of people with MCI develop AD each year. This morbidity is 10 times than of the general population. Therefore, early screening and intervention of MCI patients has a great significance to delay or prevent MCI developing to AD. The purpose of the current study was to conduct an epidemiologic investigation among the community senior citizens of Changsha City and analyze possible relevant factors.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Residents >60 years of age who live in urban areas of Changsha >1 year were recruited as subjects. These persons had clear minds, an ability to understand and cooperate, and a willingness to take part in this investigation. None of the subjects had any hearing or visual impairments. Those who were seriously disabled and weakened and who could not finish this investigation were excluded.

Methods

Research design:This research adopted a cross-sectional study. Two districts (Furong District and Yuelu District) were selected by multi-stage cluster sampling from five districts (Furong, Tianxin, Yuelu, Kaifu, and Yuhua) in Changsha City between April and September 2012. Two streets (Jiucaiyuan Street and Wangyuehu Street) were selected from the two aforementioned districts, respectively. Four communities (Tangjialing, Rongyuan, Huzhong, and Hudong) were selected randomly from the two streets. Finally, 1764 senior citizens were studied.

Table investigation and evaluation:Between April and September 2012, with the support of a community resident committee and written informed consent from senior citizens, MCI preliminary screening was conducted by completing the following tables: general information survey; Mini-Mental State examination (MMSe); Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Beijing version); global Deteriorate Scale (gDS); Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale; and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale.

A table of general information survey was designed as per the investigation objective which includes name, gender, age, level of education, occupation, marital status, residence, family history, and medicine history.

The MMSe is the most powerful screening tool on cognitive function deficiency, including tests on orientation, memory, calculation, language, visual space, application, andattention. This table contains 30 items with a total score of 30. A correct answer or operation is marked with a “1,” while incorrect answers, no answer, or “incapable” is marked with a“0.” The items with a “1” are summed as the total score. With a test time of 5~10 min [13], cognitive function was considered impaired if the scores were as follows (as per level of education): illiteracy group ≤17; primary school group ≤20; and junior high school group or above ≤24.

MoCA (Beijing version) is a specialized MCI screening tool [14] used domestically and internationally, and consists of cognitive estimation based on 8 criteria, i.e., visual space application capability, naming, memory, attention, smooth language, abstract thinking, delayed memory, and orientation capability. The total score is 30 and the cut-off score is 26. For those with an education <12 years, 1 point was added to the test result to balance the education level. A higher MoCA score indicates better cognitive function. The test requires 10 min to complete [15].

gDS: This table classifies the severity of patient cognitive and social activity function. The gDS is used to determine patient stage of MCI. Based on the gDS evaluation, class 1~3 refers to preliminary or early stages of MCI, while class 4~7 represents dementia [16, 17].

CDR scale includes the following six criteria: memory; orientation; capability on judge and problem solving; work and socializing ability; family life; personal interest; and independent living ability. each aspect is evaluated by five classes from “no harm” to “most harmful.” The score of each criterion is not summed, but is calculated based on the general scoring standard to give one integrated mark for all six items. The results are indicated as 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0, which represent normal, possible dementia, slight dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. The CDR score for MCI patients is 0.5 [18].

The ADL scale is used to evaluate daily living capability of the person being studied. The ADL scale consists of 14 items and 2 parts (the first part is a self-care capability evaluation table, and includes 6 items [going to the toilet, eating, dressing, washing, walking, and bathing], and the second part is the instrumental daily living capability evaluation table, and making telephone calls, shopping, preparing meals, doing house work, washing clothes, using transportation tools, taking medicine, and self-sufficiency). A total score ≤16 is deemed normal, 16< total score ≤22 indicates declining daily living capability, and a total score >22 (or >3 items with a score >3) is considered to dysfunctional daily living [19].

Clinic assessment:As per MCI diagnostic criteria, neurology experts make a definite diagnosis based on actual conditions and survey results on MCI patients who are screened using the above tables. generally, a MCI clinical diagnosis adopts the following diagnostic criteria by Petersen [20] as the gold standard: (1) dementia and other internal diseases or psychological states which may cause brain disorders are excluded; (2) the person being studied has a deterioration in memory; and (3) based on the table assessment, there was a slightly abnormal general cognitive classification, i.e., gDS=2~3 class, CDR score=0.5, score of memory test <1.5 times the standard of age-education match, and MMSe score >24 or a Mattis dementia assessment score >123.

The diagnosis of AD was based reference on diagnostic criteria of (NINCDS/ADRDA), as follows [21]: (1) clinical signs indicate dementia and psychological testing reveals that there is obvious cognitive damage; (2) age of onset is 40~90 years, especially after 65 years; (3) there is progressive memory and cognitive impairment; (4) two or more cognitive impairments; (5) the impairments are based on unconsciousness and may be accompanied with spiritual or behavioral abnormities; and (6) other cerebral diseases which can influence memory and cognitive impairment are excluded.

Statistical methods

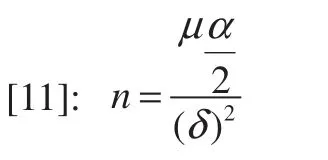

SPSS 16.0 software was used for statistical analyses. enumeration data were indicated with percentages and checked by X2. The MCI prevalence was the number of confirmed MCI patients divided by the number studied. Logistic regression analysis was used to reveal the relationship between prevalence and age, gender, and education. The test criterion was an α=0.05. The chisquare test standard on MCI prevalence for patients of different ages and education were 0.0125 and 0.0031, respectively.

Results

MCI prevalence for senior citizens in communities in Changsha City

A total of 1764 senior citizens >60 years of age were investigated. A definitive diagnosis was made by neurologists withreference to the survey results and 287 persons were diagnosed with MCI, indicating a MCI prevalence of 16.27%.

Single factor analysis on MCI prevalence for senior citizens with different demographic characteristics

There was no statistical significance (P>0.05) to compare MCI prevalence for those persons of different genders, income, chronic disease, or declining memory. A comparison of MCI prevalence for senior citizens of different ages, levels of education, occupation, marital status and residence was statistically significant (P<0.05). Among these persons, the MCI prevalence increased as a function of age >60, 70, and 80 years. People with a level of education above junior high school had a lower MCI prevalence than the illiteracy group, indicating this difference was statistically significant (P<0.0125 or 0.0031; Table 1).

Logistic regression analysis on factors related to the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment for senior citizens in communities in Changsha City

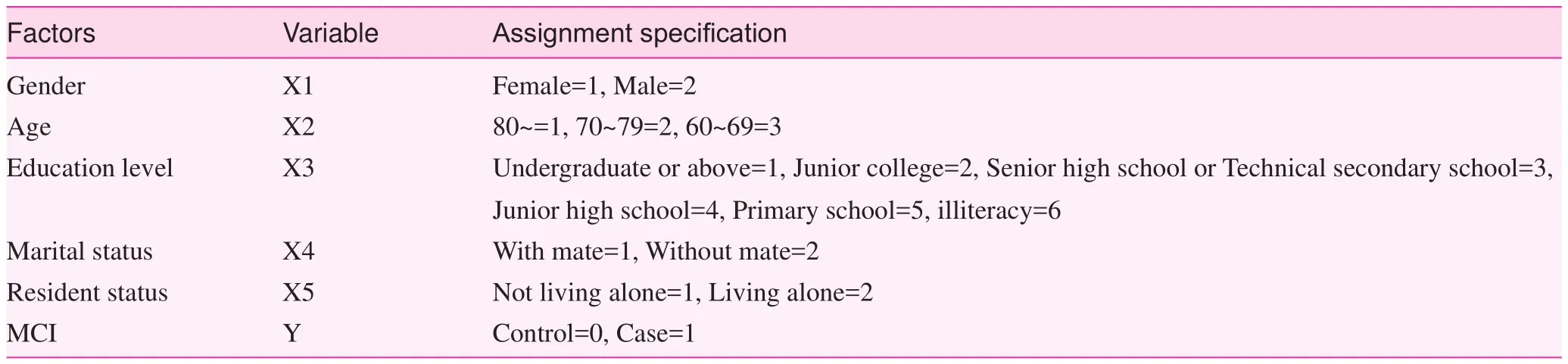

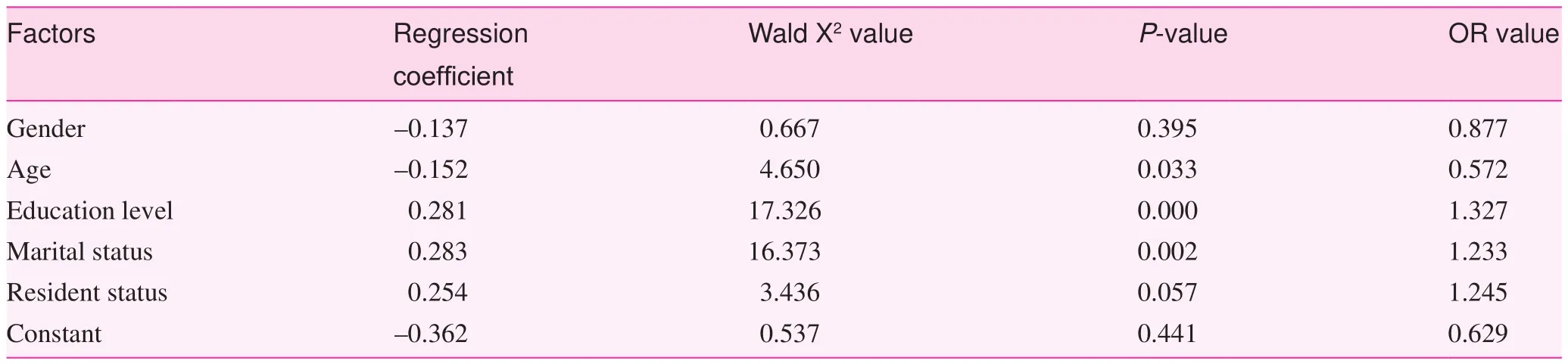

Based on standards of αin=0.10 and αout=0.15, the logistic regression analysis adopted independent variables, such as gender, age, level of education, marital status, and residence, and the presence of absence of MCI was the dependent variable (Table 2). Age, level of education, and marital status were considered in the regression (P<0.05, Table 3).

Comparing MCI prevalence of senior citizens between communities in Changsha City and other cities

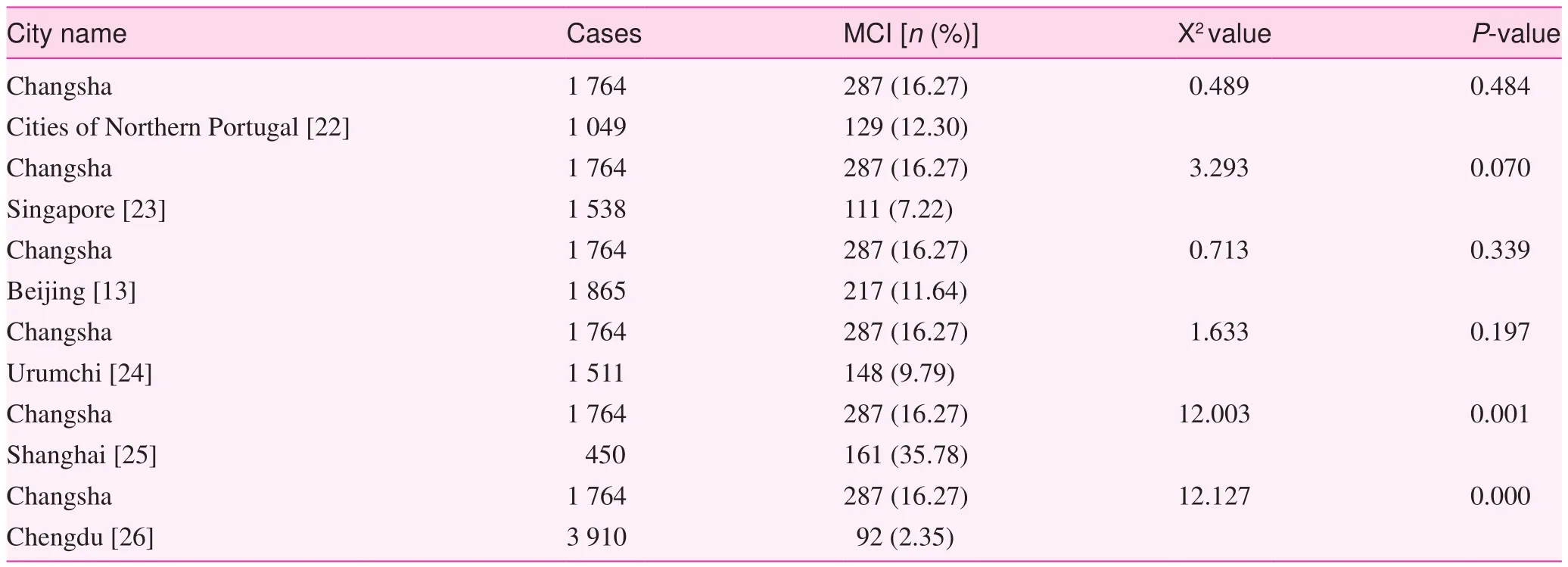

A comparison of MCI prevalence for senior citizens residing in communities in Changsha City with senior citizens in Portugal, Singapore, Beijing, and Urumchi was not statistically significant (P>0.05). The MCI prevalence for senior citizens in communities in Changsha City was higher than Chengdu, but lower than Shanghai; this difference was statistically significant (P<0.05, Table 4).

Discussion

This survey revealed that the MCI prevalence among the community senior citizens of Changsha City did not differ from other cities, such as Portugal, Singapore, Beijing, and Urumchi. This rate, however, was higher than Chengdu. This result may be influenced by the fact that people 55~59 years of age have slower cognitive decline than people >60 years of age who were included in the investigation. Because cognitive function declines as age increases, the MCI prevalence among the community senior citizens of Changsha City was lower than Shanghai, which may have been caused by the fact that the subjects in Shanghai were 70~80 years of age (48.9%) and people >80 (39.8%) years of age account for a larger proportion than Changsha. Other than differences on research tools and diagnosis standards, factors such as age, level of education, and marital status also contribute to the differences in the MCI prevalence [27, 28].

The results of this survey reveal that the MCI prevalence of senior citizens in communities of Changsha City is increasing along with the increase in age. The higher the education, the lower the MCI prevalence is. This finding is consistent with most domestic and overseas research [12, 25, 29–33]. Age is an important risk factor influencing the MCI prevalence. Some researches consider that the nervous system is declining and cognitive function is damaged due to increasing age [29]. Some researchers believe that the association between aging and cognitive decline is due to dopamine neurotransmitters; specifically, the activity of dopamine neurotransmitters declines with aging, resulting in hypofunction of the fronto-striatal system, such as declining of the following capabilities: speed of movement; abstract thinking; attention; words learning; and memory [34]. Other researches have proven that the function of the central cholinergic system may have a great influence on cognitive function; specifically, reducing acetylcholine will result in a decline of cognitive function with an increase in age [35, 36].

The level of education is a protective factor for cognitive function because education may provide more cognitive knowledge to individuals and prevent a decline in cognitive function [12]. Some scholars believe that higher education keeps the brain active so as to maintain or promote development of cognitive function [37, 38]. Therefore, to delay aging, senior citizens are recommended to practice their memory through reading, writing, playing crossword puzzles, group discussion, and listening to music [30, 39, 40].

The results of this survey also indicate that living without a mate is a high risk factor for the MCI prevalence. This finding is in agreement with the results of previous research[41–43]. Senior citizens with mates have better psychological states [44] and healthier lifestyles [45] than those without mates, and they have more social support [46], which delays the decline in cognitive function.

Table 1. Single factor analysis on MCI prevalence for senior citizens with different demographic characteristics

The results of this survey did not show that gender has an influence on the MCI prevalence for senior citizens in communities of Changsha City. This finding is consistent with the results of Zhuo et al. [41]. However, some domestic andinternational studies have shown out that the MCI prevalence of males is higher than females, and the difference is of statistical significance [32, 42, 47]. According to the extensive systematic literature analysis by Kryscio et al. [33] gender is not a risk factor related to the MCI prevalence, so further research is needed to determine if gender is a risk factor for the MCI prevalence.

Table 2. Variable assignment for regression analysis on factors related to MCI prevalence for senior citizens in communities in Changsha City

Table 3. Regression analysis on factors related to MCI prevalence for senior citizens in communities in Changsha City

Table 4. Comparison of the MCI prevalence among the senior community citzens of Changsha City with other cities

Confict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. State Statistics Bureau of the People’s Republic of China. Data Report of the Sixth National Demographic Census (No. 1). [accessed 2011 April 08]. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/ tjfx/jdfx/t20110428_402722253.htm.

2. Lin T, Huang J, Jiang X. Urban senior citizen’s needs on health services, using and nursing strategy. Chin Nurs Magaz 2005;40:628–30.

3. Xinhuanet. Publishing of the first blue book on services for the aging, aging brings challenge. [accessed 2013 February 28]. Available from: http://news.Xinhuanet.com/politics/2013-02/28/c_114828918. htm.

4. Xiao S, Xue H, Li g, Li X, Li CB, Wu WY, et al. Memory declining caused by slight damage of cognitive function for senior citizens. Magaz Chin gen Pract Magaz 2006;5: 340–5.

5. Henderson S. epidemiology of dementia. Ann Med Int (Paris) 2008;149:181–6.

6. Alzheimers Association. 2011 Alzheimers disease facts and figures. Alzheim Dement 2011;7:1–33.

7. McKibbin CL, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale J, Archuleta C, von Kanel R, Mills P, et al. Sleep in spousal caregivers of people with Alzheimers disease. Sleep 2005;28:1245–50.

8. Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, Shea D. Spouses of persons with dementia: their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Health 2004;27:296–306.

9. Okonkwo OC, griffith HR, Copeland JN, Belue K, Lanza S, Zamrini eY, et al. Medical decision-making capacity in mild cognitive impairment: a three-year longitudinal study. Neurology 2008;71:1474–80.

10. Liu-Ambrose TY1, Ashe MC, graf P, Beattie BL, Khan KM. Increased risk of falling in older community-dwelling woman with mild cognitive impairment. Phys Ther 2008;88:1482–91.

11. Jiang Q. Study on epidemic disease. Beijing: Science Press, 2003. p. 75.

12. Tang Z, Zhang X, Wu X, Liu HJ, Diao LJ, guan SC, et al. Investigation on slight cognitive disorder rate for urban and rural senior citizens in Beijing. Chin Psychol Health Magaz 2006;21:116–8.

13. Zhang M, Yu e, He Y. Investigation tools and its application on epidemic disease of demented. Shanghai Psychol Med 1995;7 (Supplementary Magazine):1–62.

14. ge P. Montreal cognitive assessment table and clinical test on patients with slight damage of cognitive function. Stubborn Dis Magaz 2012;11:45.

15. Wang W, Wang L. “Montreal Cognitive Assessment Table” used in screening on patients with slight damage of cognitive function. China Int Med Magaz 2007;46:414–6.

16. Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatr 1982;139:1136–45.

17. Zhang M. Manual of assessment table on psychiatry. 2rd Version. Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press, 1998. p. 56.

18. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–4.

19. Pan H, Wang J, Li S, Wu ML, Chen JY. Investigation and analysis on senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function in communities in Jinhua city. Chin Pract Nurs Magaz 2012;28:80–2.

20. Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1985–92.

21. McKhann g, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan eM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzhermer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzhermer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–44.

22. Nunes B, Silva RD, Cruz VT, Roriz JM, Pais J, Silva MC. Prevalence and pattern of cognitive impairment in rural and urban populations from Northern Portugal. BMC Neurol 2010;10:42–9.

23. Hilal S, Ikram MK, Saini M, Tan CS, Catindig JA, Dong YH, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in Chinese: epidemiology of Dementia in Singapore study. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2013;84:686–92.

24. Zhu X, Zhou X, Kumusi B, Yue YH, Zhao RJ, Xing SF, et al. Investigation on senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function in communities in Urumchi. J Sinkiang Med Univ 2009;32:578–80.

25. Bai J, Feng X, Jin J, Xie SZ. Investigation on senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function. Pract Nurs Magaz 2003;19:58–65.

26. Qiu C, Tang M, Zhang W, Han HY, Dai J, Lu J, et al. Investigation on prevalence rate of people above 55 years old with slight damage of cognitive function. Chin epid Dis Magaz 2003;24:1104–6.

27. Chen R, Jiang X, Zhao X, Qin YL, gu Z, gu PL, et al. Analysis of risk factors on type 2 diabetic patient with slight damage of cognitive function. Chin gen Pract Med 2012;15:2758.

28. Yin S, Nie H, Xu Y. Research on prevalence rate and dangerous factors of senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function. Chin gen Pract 2011;14:4145.

29. Liang W, Qu C, Ma F. Status investigation on senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function in communities in Taiyuan city. Chin Chron Dis Prev Control 2008;16:174–5.

30. Zhou D, Xu Y, Chen Z, Hu ZY, Chen YF. Investigation on prevalence rate of senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function. Chin Pub Health 2011;27:1375–7.

31. van Hooren SA, Valentijn AM, Bosma H, Ponds RW, van Boxtel MP, Jolles J. Cognitive functioning in healthy older adults aged 64–81: a cohort study into the effects of age, sex, and education. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2007;14:40–54.

32. Das SK, Bose P, Biswas A, Dutt A, Banerjee TK, Hazra AM, et al. An epidemiologic study of mild cognitive impairment in Kolkata, India. Neurology 2007;68:2019–26.

33. Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Salazar JC, Mendiondo MS, Markesbery WR. Risk factors for transitions from normal to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Neurology 2006;66:828–32.

34. Mozley PD, Acton PD, Barraclough eD, Pl?ssl K, gur RC, Alavi A, et al. effects of age on dopamine transporters in healthy humans. J Nucl Med 1999;40:1812–7.

35. Tomimoto H, Ohtani R, Shibata M, Nakamura N, Ihara M. Loss of cholinergic pathways in vascular dementia of the Binswanger type. Dement geiiair Cogn Disord 2005;9:282–91.

36. Li H, Wu M, Yao M, Zhao WM, Xu LR. Senior citizens’ slight damage of cognitive function and its relation with oxygen radical metabolism, acetylcholine esterase, blood fat and inflammatory medium. Clin Neurol Magaz 2008;21:201–3.

37. Stem Y. The concept of cognitive reserve: a catalyst for research. Clin exp Neuropsychol 2003;25:589–93.

38. Coyle JT. Use it or lose it – do effortful mental activities protect against dementia? N engl Med 2003;348:2489–90.

39. He X, Wang C. Illness and dangerous factors for senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function. Modern Med 2013;15:47–8.

40. Verghese J, LeValley A, Derby C, Kuslansky g, Katz M, Hall C, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of amnestic mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Neurology 2006;66:821–7.

41. Zhuo CJ, Huang YQ, Liu ZR. Prevalence rate of patients with slight damage of cognitive function in urban and rural communities in Beijing. Chin Psychol Health Magaz 2012;26: 754–60.

42. Tognoni g, Ceravolo R, Nucciarone B, Bianchi F, Dell’Agnello g, ghicopulos I, et al. From mild cognitive impairment to dementia: a prevalence study in a district of Tuscany, Italy. Acta Neurol Scand 2005;112:65–71.

43. Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: a community – based longitudinal study. Lancet 2000;355:1315–9.

44. Berkman LF. Which influences cognitive function: living alone or being alone? Lancet 2000;355:1291–2.

45. van gelder BM, Tijhuis MA, Kalmijn S, giampaoli S, Nissinen A, Kromhout D. Physical activity in relation to cognitive decline in elderly men: the FINe Study. Neurology 2004;63:2316–21.

46. Wang HX, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late – life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. Am J epidemiol 2002;155:1081–7.

47. Pan Z, Zhou R, Wang T, Xiao SF. Investigation on prevalence rate of senior citizens with slight damage of cognitive function in communities. Med Health Care Citizen 2012;18:154–6.

1. Urology Department, The First People’s Hospital of Changde, Hunan 415000, China

2. School of Nursing, Central South University, Hunan 410008, China

Hui Zeng

School of Nursing, Central South University, Hunan 410008, China e-mail: zenghuiy100@yahoo. com.cn

15 October 2013;

Accepted 5 December 2013

Family Medicine and Community Health2013年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2013年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- The ‘physical-mental’ treatment of cardiovascular disease co-morbid with mental disorders

- Economic burden of inpatients with viral hepatitis B-related diseases and the infuencing factors

- Memory and behavior-related problems of patients with neurocognitive disorders and the attitudes of their caregivers

- Health-related behaviors in children of ethnic minorities and Han nationality in China

- Development of community health service-oriented computerassisted information system for diagnosis and treatment of respiratory diseases

- Family Medicine and Community Health