The Changing Global Context of China-EU Relations

I.Introduction

The world within which the EU and China have to deal with each other is changing.The unipolar moment is definitely fading and slowly gives way to an international system characterized by multilayered and culturally diversified polarity.This development has far-reaching consequences for the EU-China relationship; the more so since the EU and China have distinctive identities and define their value preferences differently.1Gustaaf Geeraerts, “China, the EU, and the New Multipolarity”, European Review 19 (1), 2011,pp.57-67.

China is no longer the developing country it once was and is becoming more assertive.Beijing is at the head of the world’s most successful economy and will weigh more and more heavily on global governance.2Shen Qiang, “Subtle Changes in Relations among Key Players in the Reform of the International Financial and Economic System”, Foreign Affairs Journal 21 (92), 2009, pp.33-55.Three decades of impressive economic growth have boosted the self-confidence of the Chinese leaders significantly.In Beijing the notion that China should start taking an attitude,befitting a great power is gaining ground.China is taking up ever more space within various multilateral organizations and is setting up diplomatic activities throughout the globe.Moreover, Beijing has become more active in setting up its own multilateral channels to further its national interests and own norms.China no longer considers itself an outsider that should crawl back into its shell and steer well clear of a global political system dominated by the West.

All this has started to put into question the EU’s longtime conditional policies towards China, which are based on the assumption that China can be socialized and persuaded to incorporate Europe’s postmodern values.The way ahead seems rather for Europe to opt for a more pragmatic approach, which takes stock of the changes in the underlying power and identity relations between the EU and China.

China no longer considers itself an outsider that should crawl back into its shell and steer well clear of a global political system dominated by the West.

The analysis of this paper will be developed at three levels.First,it examines the changes in the structure of international politics.To what kind of structure are we evolving and where do China and the EU fit in? Second, it takes a closer look at the respective identities of China and the EU and explicates the major differences between them.Finally, the paper appraises the implications of the emerging multilayered and culturally diversified polarity for the further development of the EU-China relationship.

II.The Emerging Multipolar World: Multilayered and Culturally Diversified

The structure of the international system is changing with the evaporation of America’s unipolar moment.“The decline of U.S.primacy and the subsequent transition to a multipolar world are inevitable”, Wang Jisi wrote in 2004.3Wang Jisi, “China’s Search for Stability with America”, Foreign Affairs 84 (5), 2005, p.39.More recently John Ikenberry stated that “The United States’ ‘unipolar moment’ will inevitably end.”4G.John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West.Can the Liberal System Survive?”, Foreign Affairs 87 (1), 2008, p.23.Not only has the influence of the lonely superpower severely been affected by the expensive wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; its economic clout too has declined faster than ever before and its soft power is increasingly contested.At the same time China is undeniably becoming a global power.Since the cautious opening up of China’s door by Deng Xiaoping in 1978 her economy has quadrupled in size and some expect it to double again over the next decade.China is about to become the second most important single economy in the world.

But China is not only growing economically, also its military clout is on the rise.5See IISS, The Military Balance, London, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2007, pp.346-351.In 2008 China evolved into the world’s second highest military spender.6See SIPRI, SIPRI Yearbook 2009.Summary, Stockholm, SIPRI, 2009, p.11.It is the only country emerging both as a military and economic rival of the US and thus generating a fundamental shift in the global distribution of power and influence.Such power transitions are a recurring phenomenon in international politics and have always constituted episodes of uncertainty and higher risk.They contain the seeds of fierce strategic rivalry between the up-and-coming state and the residing leading power, thereby increasing the likelihood of contention and conflict.No wonder that China’s spectacular economic growth and increasingly assertive diplomacy have incited other key-players to ponder how Beijing will seek to manage this transition and even more how it will use its leverage afterwards.Notwithstanding that China still sees itself partly as a developing country it is becoming more confident in its rising power and status.As its economic interests abroad are expanding, so will the pressure increase to safeguard them more proactively.National security is no longer solely a matter of defending sovereignty and domestic development.It also becomes necessary for China to back up its growing interests oversees with a more robust diplomacy and security policy.

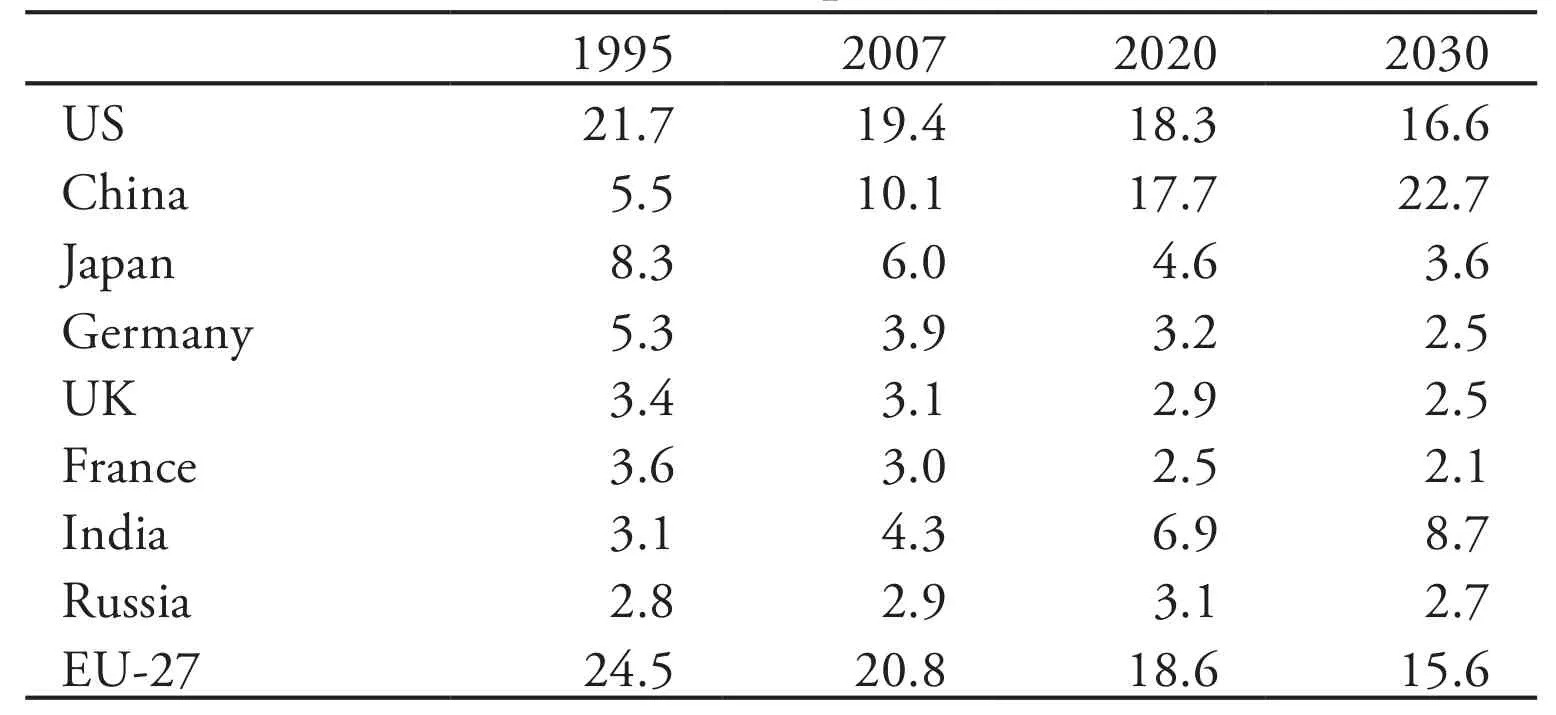

According to some estimates,China will move on a par with the US in 2020 and become the world’s biggest economy in 2030.

To be sure, the US is still the most important single economy in the world.It also remains the world’s largest military power.While the EU has developed into an even larger economy and has become the most important entity in terms of external trade flows, politically and militarily it performs far below its potential and is no match neither for the US nor China.The EU’s foreign policy is confronted with a collective action problem of sorts and as a result is lacking in both strategic vision and assertiveness.Although still smaller than the other two China has grown into the world’s second largest national economy and also the one that grows most quickly.According to some estimates, China will move on a par with the US in 2020 and become the world’s biggest economy in 2030.7See Table 1.Moreover China is steadily increasing its military power.In Beijing’s view economic prowess is not sufficient for a state to become a first rank power.“What is important is comprehensive national power, as shown by the ability of the Soviet Union to balance the much wealthier US in the Cold War and the continuing inability of an economically powerful Japan to play a political role”.8Christopher R.Hughes, “Nationalism and Multilateralism in Chinese Foreign Policy:Implications for Southeast Asia”, Pacific Review 18 (1), 2005, pp.119-135.This view is very much in line with the neorealist conception that to be considered a ‘pole’ a country must amass sufficient power in all of Waltz’s categories of power: “size of population and territory, resource endowment, economic capability,military strength, political stability and competence.”9Kenneth Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics”, International Security 18(2), 1993, p.50.

Table 1.The Trend towards Multipolarity: Share of World GDP

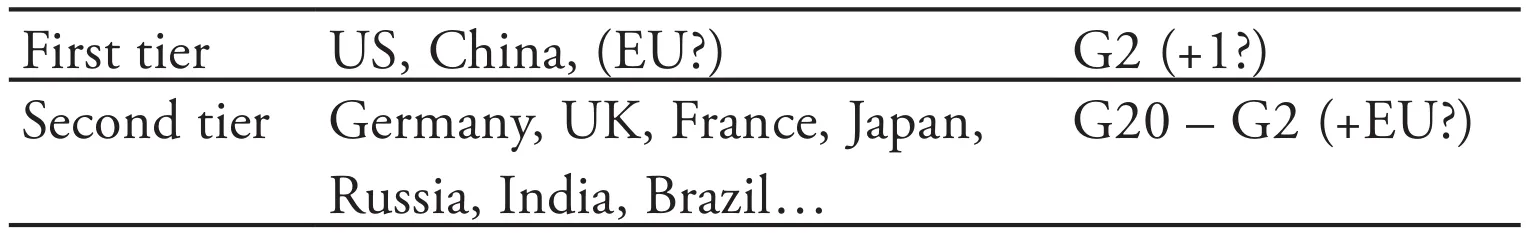

The emerging multipolar structure is a multilayered one: it consists of two tiers.In the first tier we have the US and an ever more powerful China.10Comprehensive national power (CNP), is an indicator used by Chinese scholars to aggregate economic, political and military sources of power.China has climbed up onto the fourth rank,behind the United States, Japan and Germany.According to these assessments, China has already attained a higher ranking in terms of political, diplomatic, economic, and military capabilities.The second tier comprises most regional powers like India,Brazil, South Africa, Russia, Japan, the large European states and the remaining members of the G20.They matter in a number of important international issue areas but are lacking in comprehensive power.Yet their weight is such that it is key for the first tier players to take them in account.The EU because of its share of world GDP and world trade could be a first tier actor, but to fully qualify it would have to upgrade its actorness: economic capability, political competence and military strength.Whilst the EU has developed into the world’s largest economy and is the most important entity in terms of external trade flows, politically and militarily it performs far below its potential and in terms of comprehensive power is no match neither for the US nor China.The EU’s foreign policy is confronted with a collective action problem of sorts and as a result is lacking in both strategic vision and assertiveness.11S.Rosato, “Europe's Troubles: Power Politics and the State of the European Project”,International Security 35(4), 2001, pp.45-86.

Table 2.Multilayered Polarity

China’s ascent engenders a fundamental change in yet another sense.Because of China’s being different in terms of culture, history,economy, political system and stage of development it poses a challenge to the era of Western hegemony at the level of system values and rules of the game.All these differences reduce the likelihood that Beijing will easily accept the systemic responsibilities that Western key players associate with great power status.Therefore, the “integration of China into the existing global economic order will thus be more difficult than was, say, the integration of Japan a generation ago.”12G.John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West.Can the Liberal System Survive?”, Foreign Affairs 87 (1), 2008, p.23.

China’s rise is not only changing the distribution of power in the system, it also engenders a change in the distribution of identities.

China’s rise is not only changing the distribution of power in the system, it also engenders a change in the distribution of identities.Understandably, the US and the EU would prefer to integrate China in the global governance structures they established and safeguarded in the past few decades and hope for a reproduction of the existing system.Yet it is far from clear how Beijing will seek to manage its position in the evolving international system and how it will strike the balance between power politics and multilateralism.Some point out that precisely during critical power transitions many emerging powers in the past have relinquished their resistance against imperialist policies by gradually starting to apply the very strategies themselves: the use of coercion to chase unequal economic gains,the creation of spheres of influence and the formation of alliances to prevent hostile powers from obstructing these ventures.Some expect that China too will inevitably go down this road.13John Mearsheimer, “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics”, W.W.Norton, 2001, pp.145;Robert Kagan, “The illusion of managing China”, The Washington Post, May 13, 2005; Richard Bernstein and Ross Munro, “The Coming Conflict with America”, Foreign Affairs 76 (2), 1997,pp.18-32.They expect power politics to gradually take the upper hand.Others point out that China is developing within a system with strongly established international institutions, which it makes ample use of to sustain its growth.14Marc Lateigne, China and International Institutions: Alternate Paths to Global Power,Routledge, New York, 2007, p.1.As China is already firmly integrated in the current international regimes and benefits from their smooth functioning,they expect multilateralism to be a crucial ingredient of Beijing’s foreign policy.Beijing actually has a profound interest in seeing that the international rules and institutions function effectively.Yet the question remains to what extend Beijing will use its growing influence to transform the international system and bring its rules and institutions more in line with the country’s national interests.15Ibid.

III.China’s Identity: Power Politics and Neo-mercantilism

It has to be said that, for the most part, the Chinese elite has managed to keep a low profile and assess China’s capabilities and resources rather aptly throughout.Pragmatism reigns supreme, and there is ample cause for this.Despite the fact that China has made enormous progress in the 30 years since the launch of the economic reforms,developing into the world’s leading trading power,16Editorial, Pékin et l’Asean , Le Monde, January 1, 2010.it still does not score very highly in terms of GDP per capita.In addition, it is also increasingly faced with the fallout generated by the widening gap in levels of prosperity between different regions, urban and rural areas,the rich and poor.Finally, the ecological degradation of the land is spreading ever more rapidly.In view of these factors, Chinese leaders are steering a course where what is needed for the development at home defines the contours of foreign policy.

China’s ambitions have to be limited.The current leadership can only maintain its position if it manages to resolve the many problems China faces within a reasonable timeframe.The economic engine must be kept running at all cost, an impossible feat without stable relations with its Asian neighbours and the global community.Beijing has a difficult time navigating between the two dimensions of China’s identity.It is constantly involved in a tug-of-war between its “weak power identity” (developing country) and “strong power identity”(great power).It is why China’s foreign policy appears so inconsistent at times.While Beijing’s foreign policy rhetoric at present points in the direction of a China as responsible global power, there are countervailing pressures.As economic growth continues the need for energy and other strategic resources increases accordingly.Sustainable economic development in a peaceful way may be the final goal, but it cannot be realized without secured access to strategic resources and safe trading routes.Should these become endangered, the nation’s wholesale development will be compromised, and consequently the outright survival of the regime would be in jeopardy.This is a tight corner to be in, a kind of self-reliance dilemma if you wish.In such condition it is only natural to put one’s own pressing interests first whenever possible and to look for as many ways and places available to secure them.Like it or not, sovereignty and national core interests have to figure centre stage.

China is a “pandragon”.17Gustaaf Geeraerts and Holslag Jonathan, “The Pandragon: China’s Double Diplomatic Identity”, Asia Papers 2 (2), 2007.It has a double identity, i.e.a “weak power identity” and a “strong power identity”.At times, it considers itself a mere developing country that was wronged by the imperialists and is therefore entitled to a great degree of leniency and support.At other times, it sees itself as a great power that is well on its way to restoring the glory of the ancient empires and wants to be treated on an equal footing.That is why Beijing is so sensitive to be taken seriously and be treated as a peer.At the same time however, the Chinese still count on consideration from the other side, some special treatment.China although growing fast is still at a premature stage of development and has to overcome tremendous internal difficulties if it is to survive.Consequently, it cannot as yet take up the full scale of its international responsibilities.To cut a long story short: sustainable domestic economic development is the most pressing challenge; the evolution of China into a responsible global power is the long-term ambition.

On closer examination China’s developmental model and associated economic strategy is neo-mercantilist.It anxiously works to maintain equilibrium between national sovereignty and international integration, particularly between integration in the global market and economic independence.Control by the state apparatus crucially acts as a counterweight to market forces.18On neomercantilism see Robert Gilpin, The Political Economy of International Relations,Princeton, Princeton University Press,1987.The state needs to ensure that the market operates, both at home and abroad, in a way that is entirely conducive to the expansion of Chinese influence and power across the globe.At the same time, the government must make sure that this whole process generates enough prosperity, which can then,after the necessary redistributive measures, guarantee social stability and cohesion.Direct domestic investments remain crucial for further economic development and in exchange, the domestic industry must play its part, whilst the government retains a finger in every pie.Ultimately, this entire process needs to be accelerated by a go-out policy that, again under the guidance of the state, should safeguard access to foreign outlets and strategic raw materials.

IV.The EU: Reshaping the Power Paradigm?

The EU’s identity is rather distinct from that of China.It is often perceived to be a normative actor, founding its policies on values,institutions and cooperation rather than power politics.As such the EU constitutes an effort to reshape the power paradigm to reflect a new kind of power in global politics.As stated in its 2003 Security Strategy the EU aims at the “development of a stronger international society, well functioning international institutions and a rule based international order”.19European Council, A Secure Europe in a Better World: European Security Strategy, European Council, 2003, p.9The rules underpinning this new international order are to be founded on Europe’s liberal political norms, its views of an open global market and its preference for highly institutionalized multilateralism.

Similarly, the relations with the emerging powers are largely constructed from the belief that the latter should adapt their international political norms to the European standards.Normative convergence is thus the starting point for developing relations with emerging countries.

Europe’s policy towards China has to date been one of conditional cooperation.The EU is prepared to help the PRC, to invest in the development of the country, but in turn, China must meet a number of standards and demands.This is a rather unique way of dealing with a rising power.In contrast to the United States, Europe is not gearing up for a confrontation if needed.So-called “hard power” is hardly on the agenda.European nations are not taking up bases in Asia to curb Chinese influence in case this might be necessary.Power politics,based on military capabilities and threats with the use of force, seems to have disappeared from the diplomatic handbook all together.On the contrary, Europe wishes to forge a tighter link and strengthen its influence through ever-increasing economic interdependence and shared values.In this process, Europe sees itself as the model China should aspire to.EU policy is based on the belief that “human rights tend to be better understood and better protected in societies open to the free flow of trade, investment, people, and ideas.As China continues its policy of opening-up to the world, the EU will work to strengthen and encourage this trend.”20European Commission, A Long-term Policy for EU-China Relations, European Commission,Brussels, 1995, p.6.

British top diplomat Robert Cooper champions this approach in an often-quoted book, where, he talks about a post-modern security strategy with the emphasis firmly placed on values and international cooperation rather than hard power and control over territories.“Nationalism makes place for internationalism”, he writes.“The final goal is the liberty for each individual.”21Cooper Robert, The Breaking of Nations: Order and Chaos in the Twenty-First Century,Atlantic Press, 2003, p.137.

The crucial question is to what extent this approach can be actually successful.Beijing has not put democracy and respect for human rights on top of its list of priorities.In terms of foreign policy, it is unrealistic to think Beijing will comply with Europe’s “post-modern”discourse.If one, in accordance with Robert Cooper, distinguishes between “modern states” and “post-modern states”, then China is to be categorized as a “modern state”, for which “internationalism”is but one modus operandi serving the national interest.The PRC is therefore by no means at a point where it can meet the European expectations.Chinese officials, scholars and pundits all tend to indicate this when talking in private.It is crucial for the EU to be aware what power it has to sway policy in China.An important parameter in the EU’s dealings with China will be the strategic weight Brussels will be capable of bringing to bear with Beijing.China perceives the EU foremost as an economic actor, far less as a political actor.One reason why Beijing for example wants the PCA negotiations to focus on trade and economic cooperation might be that it has doubts about the EU’s capacity to deliver really in the political domain.

The EU’s success with China will to a large extent rest on recognition of common interests, in areas such as the environment and energy, but also in trade and investment.

The EU should also be critical of its leverage as a normative actor.China may well recognize the advantages of cooperating with the EU and of learning from it in certain areas, but it is certainly not willing to accept the tutelage of the EU.China is not a prospective EU member, nor does it see itself as a weak nation, depending solely on the EU for support in its political and economic reform process.The most real incentive that the EU has to offer is access to its market.The EU’s success with China will to a large extent rest on recognition of common interests, in areas such as the environment and energy, but also in trade and investment.The degree to which China’s interests match those of the EU will determine the success of relationship.

As the constellation of world power is changing, the EU’s strategy will have to change with it.Europeans must come to grips with the fact that “the West does not enjoy a predestined supremacy in international politics that is locked into the future for an indeterminate period of time.The Euro-Atlantic world had a long run of global dominance, but it is coming to an end.”22C.Layne, “The End of Pax Americana: How Western Decline Became Inevitable”, The Atlantic, April 26, 2012.The future is more likely to be shaped by Asia and China in particular.China’s mounting power and growing assertiveness poses a challenge to the EU’s standing in the international order.The growing economic weight of Asia and China’s reemergence is facing Europe with a process of de-centering.As David Kerr observes the“fact that most powers in Eurasia - and China foremost among them- are accumulating sovereignty or the means to stronger sovereignty,not sharing sovereignty as the European experience promotes, means that the European region remains quite exceptional in both its political dynamics and its strategic organization.”23D.Kerr, “Problems of Grand Strategy in EU-China Relations”, in J.v.d.Harst and P.Swieringa(eds.), China and the European Union.Concord of Conflict?, Maastricht: Shaker Publishing, 2012,pp.69-88.Even if China will continue to defend its interests in a peaceful way, partially by nourishing its bilateral relations, partially by working via multilateral institutions, its growing capabilities ask the EU to adapt with regard to its policymaking capacity.In order to face common challenges with China and to fill the present strategic void, the EU needs to develop the capability to play a role of importance in the changing global environment.The EU has to pool the fragmented capabilities of its member states into real levers for exerting influence if it is to be taken seriously as a strategic international actor by Beijing.

The challenge will be to work out a pragmatic consensus on how to gradually turn joint strategic interests into more resultdriven cooperation.

V.Towards a Pragmatic Relationship

The Sino-European partnership has been going through turbulent times in the past few years.As it stands, the partnership is not strategic,but it has vast strategic potential.24G.Geeraerts, “EU-China Relations”, in Th.Christiansen, E.Kirchner and Ph.Murray, eds.,The Palgrave Handbook of EU-Asia Relations, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2013, pp.492-508.The challenge will be to work out a pragmatic consensus on how to gradually turn joint strategic interests into more result-driven cooperation.Given the distinctive identities of China and the EU and their different development paths,this process will inevitably have to be commensurate with the two partners’ internal transformation.25D.Freeman and G.Geeraerts, “Europe, China and Expectations for Human Rights”, in P.Zhongqi, ed., Conceptual Gaps in China-EU Relations.Global Governance, Human Rights and Strategic Partnerships, Houndmils: Palgrave, 2012, pp.98-112.After a period of difficulties over issues like Tibet, climate change and alleged economic protectionism,both sides are now figuring out how to best position themselves in the future.Beijing is executing an important review of its major relationships and one of the questions is where the EU will fit in.There is growing momentum for synergies with Washington, leading to speculation about a transpacific bargain.26A.Subramanian, “China and America should strike a bargain”, Financial Times, June 6, 2013.But in the multilayered multipolar world it will remain key for China to maintain good relations with the other powers too.For Europe, changes brought about by the Lisbon reform treaty may ultimately halt its descent into strategic redundancy and instigate the EU to assure protagonists like China that it has indeed the ambition to develop solid strategic partnerships.

The years ahead will thus be ones of relation therapy.Europe and China need to define for themselves what they consider to be the main interests driving their partnership.For the EU in particular it is a matter of finding a remedy against the kind of diplomatic schizophrenia in which short-sighted policies of the member states counteracted the proselytizing European Commission.It would be a good start to evaluate the effectiveness of the current instruments for engaging China.More efforts should also be made in bringing member states around the table to deduce a common denominator from their often-diverging national interests.If Europe is to constructively engage China, it will have to engage itself collectively first.

Simultaneously, China and Europe have to agree on which interests they will build the pillars of their strategic partnership.One of the main setbacks in the EU-China partnership has always been its obsession with dialogues without a common view on how the new world order actually binds them together.Obviously, the global financial crisis and the subsequent economic recession have confirmed the necessity to reshape our economies.Both countries face an important challenge to combat unemployment, to improve social welfare and to be more efficient in using scarce natural resources.Increased investment in innovation, a secure climate for creative development and a dynamic services sector will be vital for developing new and sustainable sources for growth.This is an individual responsibility, but it can only be successful in a climate of trust and reciprocal openness.Both sides are confronted with similar social challenges: an ageing population, a heterogeneous ethnic society, growing urban complexes and substantial internal economic differences.They have a common interest in enhancing social equality and welfare.While facing different economic limitations, both sides are aiming to make their development inclusive and harmonious.Rather than lecturing each other, this brings the opportunity to exchange lessons learned.The emphasis should not be on differences per se, but on commitment and progress.

VI.Conclusion

China and Europe are both regional powers with broad global interests.As a consequence of increased international engagement and increasing economic interests abroad, Europe and China are geopolitically more proximate than ever before.There is an important joint interest to promote stability and sustainable development in those regions that we share in our extended neighbourhoods.This is particularly the case of the Middle East, Africa, and South-Central Asia.We have to avoid that these regions develop into a belt of insecurity that endangers our development.There is a strong need to work together to enhance security, to guarantee that our policies benefit lasting stability and development, to invest in the safety of our energy supplies, to limit the impact of environmental hazards, to support effective governance, tackle non-traditional security threats,and enhance maritime security.It is legitimate that growing interests bring the need to exert influence, but this should be cooperative and aim at sharing the costs of maintaining security.

We are moving steadily towards a new multipolar world order.In this order the major powers will have to balance between meeting increasing international expectations and persistent strong internal needs.The emerging multilayered and culturally diversified multipolarity will make global governance much more complex and is by no means a guarantee for multilateralism.To be effective multilateral organizations need to reflect the emerging new international order, but effective multilateralism also implies that all parties are committed to overcome diverging expectations and try to reach a pragmatic consensus on how to make foreign policies complementary and mutually supportive.Europe and China could be in the vanguard here as well.

As the unipolar moment fades, Europe and China have showed themselves anxious not to slide into another era of great power rivalry.Such contest would severely weaken the two player’s chances for sustainable internal development.In spite of all the friction and misunderstanding, both sides need each other if they are to develop an alternative for harsh international anarchy.Successful bilateral cooperation will be key in promoting global peaceful development.It will also give them the scope to strengthen their internal unity,which will be key in boosting positive power vis-à-vis others.If Beijing and Brussels are serious about changing the nature of great power politics, a pragmatic partnership between China and Europe build on mutual benefit, trust and understanding is mandatory.