Susceptibility weighted imaging in the evaluation of hemorrhagic dif use axonal injury

Susceptibility weighted imaging in the evaluation of hemorrhagic dif use axonal injury

Dif use axonal injury (DAI) is axonal and small vessel injury produced by a sudden acceleration of the head by an external force, and is a major cause of death and severe disability (Paterakis et al., 2000). Prognosis is poorer in patients with apparent hemorrhage than in those without (Paterakis et al., 2000). Therefore, it is important to identify the presence and precise position of hemorrhagic foci for a more accurate diagnosis. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have long been applied in the diagnosis of DAI, but they are not sensitive enough for the detection of small hemorrhagic foci, and cannot meet the requirements for early diagnosis. A major advance in MRI has been the development of susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI), which has greatly increased the ability to detect small hemorrhagic foci after DAI (Ashwal et al., 2006). In this study, we retrospectively analyzed MRI data for 25 patients with hemorrhagic DAI verif ed by clinical imaging, and we explored whether SWI was suf ciently sensitive to evaluate hemorrhagic DAI and help accurately assess the severity of the disease.

We recruited 25 patients with hemorrhagic DAI verif ed by clinical imaging from the Wuxi No.2 People’s Hospital Af liated to Nanjing Medical University in China from December 2007 to June 2014.

Inclusion criteria: (1) history of head trauma; (2) coma or progressive unconsciousness immediately after injury; (3) no clear signs of nervous system localization; (4) unclear changes by cranial CT, severe clinical manifestation; (5) MRI reveals hemorrhagic foci (usually, diameter ≤ 20 mm) in the corpus callosum, brain stem, corticomedullary junction or cerebellum; (6) the disease allows MRI examination.

Exclusion criteria: (1) history of brain injury; (2) malformations or developmental disorders of the central nervous system; (3) history of cerebral hemorrhage or infarction; (4) presence of other diseases unrelated to the trauma which may af ect consciousness; (5) poor cooperation resulting in poor image quality.

The 25 patients comprised 19 males and 6 females, 13–49 years of age (average: 37.7 years). Of these, 18 cases were injured by road accident, 5 cases were injured by falling, and 2 cases by hitting. Patients on admission were graded in accordance with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Feng et al., 2014). The scale is composed of three tests: eye, verbal and motor responses. The sum of the three aspects represents the degree of disturbance of consciousness. The scores range from 3 (deep unconsciousness) to 15 (fully awake). Generally, brain injury is classified as follows: mild, GCS 13–15; moderate, GCS 9–12; and severe, GCS < 3–8. Among our patients, f ve scored 9–15 (mild and moderate) and 20 scored 3–8 (severe).

MRI was performed 1 day to 1 week after injury. Restless patients were intravenously given 5–10 mg diazepam before examination. Critically ill patients were monitored using electrocardiogram (ECG) gating and respiratory gating. Transverse scanning of the skull was conducted with a Signa EXCITE 1.5 T HD TwinSpeed MR scanner (GE, USA) and an 8-channel head coil. Scanning setup was as follows: fast inversion recovery (FIR) T1WI (repetition time, 1,740 ms; echo time, 21 ms; time of inversion, 720 ms), fast spin echo T2WI (repetition time, 3,900 ms; echo time, 115 ms), f uid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (repetition time, 8,600 ms; echo time, 121 ms; time of inversion, 2,100 ms), spin echo-echo planar imaging diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) (repetition time, 6,000 ms; echo time, 81 ms; b = 0, 1,000), gradient echo (GRE) T2*WI (repetition time, 640 ms; echo time, 15 ms), slice thickness, 5 mm; and gap, 1 mm. SWI used high-resolution three-dimensional GRE (repetition time, 42 ms; echo time, 25 ms; slice thickness, 2 mm; no gap scanning; 116 layers; number of excitations, 0.75. Two groups of images were collected, magnitude images and phase images, which were loaded into the workstation (GE ADW4.3) for post-processing. Minimum intensity projection (minIP) was utilized for reconstruction using a slice thickness of 5 mm and a gap of 1 mm. Finally, SWI images were obtained.

The position and number of hemorrhagic foci were identif ed by two experienced physicians according to the characteristics of the focal distributions (with no long continuous abnormal low-signal intensity within multiple levels of SWI), in combination with GRE and conventional methods. Inconsistent f ndings were identif ed together by the two doctors. According to the classif cation of Wang et al. (1998), DAI was classif ed as big hemorrhagic focus (20 mm≥ diameter > 10 mm) or small hemorrhagic focus (diameter ≤ 10 mm). The dif erence in the number of hemorrhagic foci detected with the various methods was compared using the k independent samples test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically signif -cant. Numerical data were analyzed using the Chi-square test. Correlation of the number of foci revealed by SWI and the GCS score was analyzed using Spearman’s method.

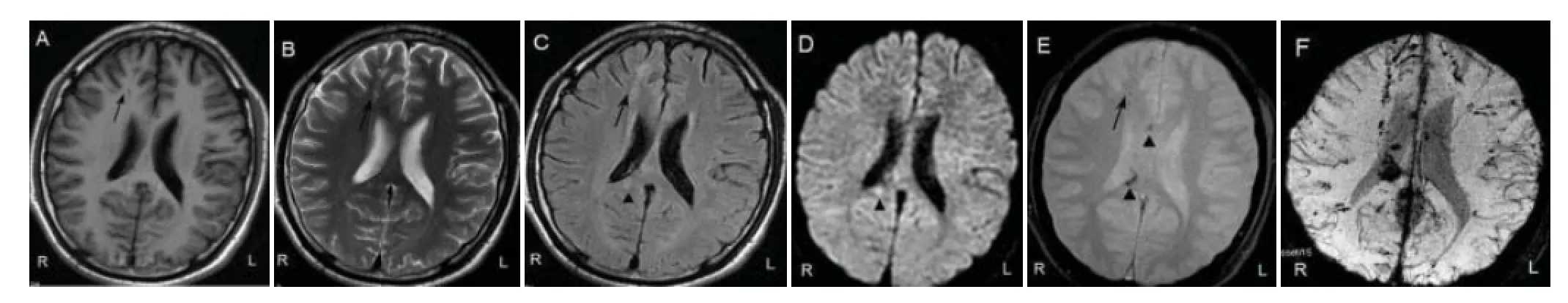

Some abnormal signals revealed by SWI were also found on T1WI, T2WI, FLAIR, DWI and GRE. Low signal intensity, high signal intensity or mixed signal intensity were detected on MRI and DWI because of dif erent bleeding time. The edge of the focus was blurred and fused into a sheet. We noted foci of low signal intensity on GRE and SWI. The images of most foci of low signal intensity on both GRE and SWI were slightly bigger on SWI than on GRE, and the signal intensity on SWI was lower than on GRE (Figure 1A–E).

Manifestations of hemorrhagic foci after DAI on SWI clearly showed the size, boundary and range of hemorrhagic foci. Spotlike, nodular, patchy and funicular low-signal-intensity foci of dif erent sizes were scattered in the predilection site. Isointense and hyperintense signals were seen in the big hemorrhagic focus. On SWI phase image, the big hemorrhagic focus displayed patchy hyperintense and hypointense signals on the central plane. The upper and lower planes near the lesions displayed low signal intensity. The small hemorrhagic focus exhibited low signal intensity. The diameter of the hemorrhagic focus was 1–20 mm (Figure 1F).

A total of 632 hemorrhagic foci were detected in 25 patients with DAI. In a single case, the number of hemorrhagic foci was a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 84. The hemorrhagic foci were mostly found in the white matter and corticomedullary junction (436, 68.99%), followed by the basal ganglia (90, 14.24%), corpus callosum (70, 11.08%), cerebellum (22, 3.48%) and brain stem (14, 2.21%).

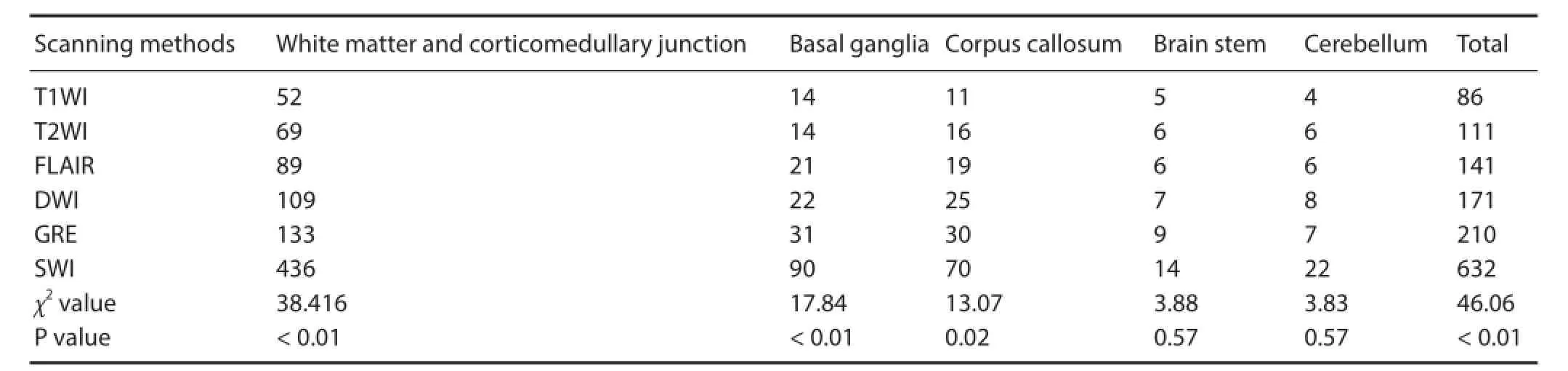

Comparison of the number and distribution of the hemorrhagic foci as detected by the dif erent scanning methods is provided in Table 1. Signif cant dif erences in the number of hemorrhagic foci were found among the various scanning methods (χ2= 46.06, P <0.01). According to average rank, the highest number of hemorrhagic foci was detected by SWI (average rank: 120.20), followed by GRE (average rank: 85.22), DWI (average rank: 77.08), FLAIR (average rank: 68.62), T2WI (average rank: 58.02) and T1WI (average rank: 43.86). There were signif cant dif erences in the number of hemorrhagic foci in the dif erent regions (white matter, corticomedullary junction, basal ganglia and corpus callosum) among the various scanning methods (P < 0.05). Although SWI detected the highest number of hemorrhagic foci, no signif cant dif erence in the number of hemorrhagic foci in the brain stem or cerebellum was found among the dif erent scanning methods (P > 0.05).

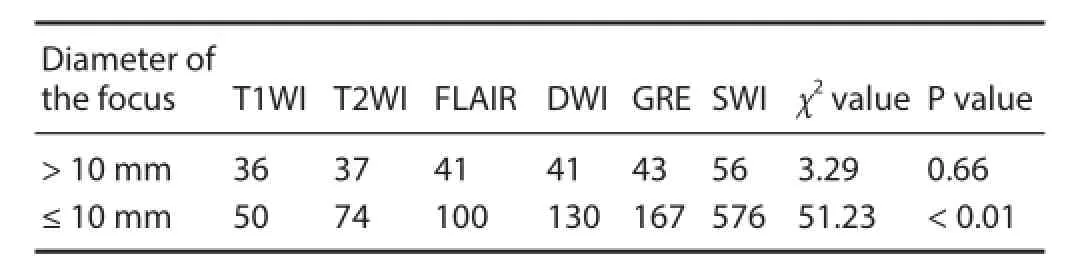

The number of hemorrhagic foci of dif erent sizes detected by the various methods following DAI is shown in Table 2. No signif cant dif erence in the number of big hemorrhagic foci (20 mm≥ diameter > 10 mm) was observed among the various scanning methods (P = 0.66). However, signif cant dif erences in the number of small hemorrhagic foci (diameter ≤ 10 mm) were seen among the various scanning methods (P < 0.01). According to average rank, the highest number of small hemorrhagic foci was detected by SWI (average rank: 121.68), followed by GRE (average rank: 86.28), DWI (average rank: 78.42), FLAIR (average rank: 69.06), T2WI (average rank: 55.90) and T1WI (average rank: 41.66).

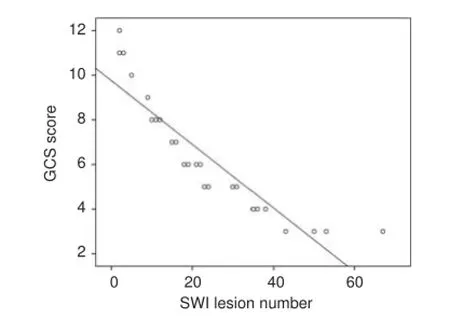

The number of hemorrhagic foci detected by SWI was signif -cantly negatively correlated with GCS score in the 25 patients (r =–0.82, P < 0.01; Figure 2).

Table 1 Comparison of the number and distribution of hemorrhagic foci in 25 patients with diffuse axonal injury detected by different scanning methods

Table 2 Comparison of the number of hemorrhagic foci of dif erent sizes after diffuse axonal injury detected by the various scanning methods

Among the dif erent types of MRI, T1WI and T2WI are used to reveal morphological changes in brain tissue after injury. T2WI and FLAIR are used to observe non-hemorrhagic high-signal-intensity foci. Fast spin echo using multiple 180 rephasing pulses is not sensitive to magnetic susceptibility induced by bleeding. In addition, the signals are af ected by the duration of bleeding. Therefore, the detection rate of fast spin echo is not high. DWI is a type of MRI based on measuring the random Brownian motion of water molecules within a voxel of tissue, and is very sensitive to perifocal edema and secondary brain ischemia.

GRE sequence without rephasing pulses cannot compensate signal loss caused by an uneven magnetic f eld. The dif erence in the magnetic susceptibility between small hemorrhagic foci and surrounding normal brain tissue causes signal loss and shows low signal intensity. Thus, DAI is more sensitive to small hemorrhagic foci. SWI is also a type of GRE-T2*-weighted MRI, and uses a fully f ow compensated, long echo, high-resolution three-dimensional GRE pulse sequence to acquire images. This method exploits the dif erences in susceptibility between tissues and uses the phase image to detect these dif erences. Compared with a conventional GRE sequence, SWI is characterized by three dimensions, high resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio. Consequently, it is more sensitive to local and internal magnetic susceptibility. Most changes in magnetic susceptibility are associated with dif erent forms of iron in the blood or bleeding. Oxyhemoglobin is antimagnetic, but deoxygenated hemoglobin, methemoglobin and hemosiderin are paramagnetic. Both paramagnetic and antimagnetic substances can alter local magnetic f elds, cause proton dephasing, and show low signal intensity on SWI. Paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin is mainly found in erythrocytes associated with acute hematoma. SWI can detect the hemorrhagic focus in an early stage because of high sensitivity to proton dephasing induced by an uneven local magnetic f eld (Ashwal et al., 2006; You et al., 2010; Benson et al., 2012). In this study, the earliest detection of hemorrhagic foci was 1 day after injury.

Because of the high sensitivity of SWI to blood metabolites, SWI reveals many hemorrhagic foci after DAI. In the present study, the number of hemorrhagic foci and the amount of bleeding revealed by SWI were respectively 3–6-fold and 2-fold higher than that shown by conventional GRE sequence (Tong et al., 2003, 2004). Our results demonstrate that SWI detects the greatest number of hemorrhagic foci, followed by GRE. T1WI detected the lowest number of hemorrhagic foci. The number of foci detected using SWI was 3.28-fold that detected by conventional GRE sequence, consistent with previous studies.

We also compared the sensitivity of SWI for hemorrhagic foci of dif erent sizes. No signif cant dif erence was found in the number of big hemorrhagic foci (20 mm ≥ diameter > 10 mm) among the dif erent scanning methods, but signif cant dif erences were seen in the number of small hemorrhagic foci (diameter ≤ 10 mm) among the dif erent scanning methods (SWI detected the highest number of foci). SWI had higher sensitivity for detecting small hemorrhagic foci than other MR sequences. Furthermore, SWI displays the boundaries and extent of the hemorrhagic foci more clearly than a conventional MRI sequence or traditional GRE sequence. Therefore, SWI is a more sensitive and accurate imaging method for identifying tiny hemorrhagic foci after traumatic brain injury.

There were signif cant dif erences in the number of hemorrhagic foci detected by the various scanning methods in the various regions, including the white matter, corticomedullary junction, basal ganglia and corpus callosum. Among the dif erent scanning methods, SWI detected the greatest number of foci. Thus, SWI has obvious advantages for regions with a high number of foci, especially the basal ganglia and corpus callosum. Nevertheless, there was no signif cant dif erence in the number of hemorrhagic foci in the brain stem or cerebellum revealed by the various detection methods. This is probably associated with the low number of hemorrhagic foci in the brain stem and cerebellum after injury, as well as the severe magnetic susceptibility artifacts at the skull base-air interface. Moreover, it should be mentioned that the number of cases in this study was limited.

GCS can objectively assess the severity of traumatic brain injury, and is simple to use. In this study, we analyzed the correlation between the number of hemorrhagic foci detected by SWI and the GCS score, and found that the number of hemorrhagic foci was negatively correlated with GCS score. Therefore, SWI can objectively and accurately evaluate the severity of brain injury. A shortcoming of this study is that we did not perform long-term follow-up of the patients.

A number of problems need attention in the detection of hemorrhagic foci using SWI. For example, distinguishing these from small veins and calcif ed foci, particularly as small veins vertical to the cross section also display oval low signal intensity. Low-signal-intensity foci continuous along numerous levels should be distinguished from microhemorrhage. Calcif ed and hemorrhagic foci also show low signal intensity in SWI, but calcification is antimagnetic and hemorrhage is paramagnetic. In SWI phase images, paramagnetic substances exhibit a phase increase in the central level and phase reduction in the upper and lower levels, while antimagnetic substancesshow the opposite (Shen et al., 2009). In this study, the pathological features of hemorrhagic foci on SWI phase images were consistent with paramagnetic substances.

Figure 1 Images of the hemorrhagic focus in a 22-year-old male patient with dif use axonal injury caused by a road traf c accident.

Figure 2 Scatterplot of the correlation between the number of hemorrhagic foci detected by SWI and the GCS score.

Another issue with diagnosis is distinguishing between contusion and laceration injury. Contusion and laceration of brain often damages the cortices of stress points or contrecoup positions, and results in focal or f aky hemorrhages > 20 mm in diameter. These patients have mild clinical symptoms, and a few experience a transient coma, which do not lead to dysfunction or death. DAI frequently occurs in the corticomedullary junction, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, brain stem and cerebellum, and can produce evident dysfunction and death. Therefore, DAI can be distinguished from contusion and laceration of the brain in hemorrhage location, size, shape, distribution and clinical symptoms. A few foci that are dif -cult to identify may not be included in the tally.

Other limitations of the use of SWI in the clinic are the long scanning time, the numerous intracranial susceptibility artifacts, and overestimates of hemorrhagic foci. Consequently, long-term follow-up is needed for an accurate prognosis.

In summary, SWI is highly sensitive for the detection of hemorrhagic DAI, and can detect a higher number of small hemorrhagic foci than other MR sequences. Furthermore, SWI can accurately reveal foci characteristics and distribution. The apparently negative correlation between the number of hemorrhagic foci revealed by SWI and the GCS score can provide important information for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, SWI has clinical value in the diagnosis of DAI.

This study was supported by a grant from the Key Science and Technology Development Project of Nanjing Medical University in China, No. 08NMU054. JJT provided and analyzed data and wrote the paper. WJZ participated in study conception and design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and provided technical or material support. DW was in charge of manuscript authorization and served as a principle investigator. All authors performed the experiments and approved the f nal version of the paper.

Jing-jing Tao1,#, Wei-jiang Zhang1,#, Dong Wang1,*, Chun-juan Jiang1, Hua Wang1, Wei Li1, Wei-yang Ji2, Qing Wang2

1 Department of Radiology, Wuxi No.2 People’s Hospital Af liated to Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Wuxi No.2 People’s Hospital Af liated to Nanjing Medical University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, China

*Correspondence to: Dong Wang, wuxiwangdong@163.com. # These authors contributed equally to this work.

Accepted: 2015-09-28

orcid: 0000-0003-0137-6352 (Dong Wang)

Ashwal S, Babikian T, Gardner-Nichols J, Freier M-C, Tong KA, Holshouser BA (2006) Susceptibility-weighted imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in assessment of outcome after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 87:S50-58.

Benson RR, Gattu R, Sewick B, Kou Z, Zakariah N, Cavanaugh JM, Haacke EM (2012) Detection of hemorrhagic and axonal pathology in mild traumatic brain injury using advanced MRI: Implications for neurorehabilitation. NeuroRehabilitation 31:261-279.

Feng ZG, Li M, Xia S, Feng XQ, Wang S, Du HS, Chai C, Wang L, Wan CG (2014) Susceptibility weighted imaging and dif usion weighted imaging in diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of dif use axonal injury. Zhonghua Chuangshang Zazhi 30:33-38.

Paterakis K, Karantanas AH, Komnos A, Volikas Z (2000) Outcome of patients with dif useaxonal injury: the signif cance and prognostic value of MRI in the acutephase. J Trauma 49:1071-1075.

Shen BZ, Wang D, Sun XL, Shen H, Liu F (2009) Clinical appHcaf on of MR susceptibility weighted imaging in intracranial hemorrhage. Zhonghua Fangshe Zazhi 43:156-160.

Tong KA, Ashwsl S, Holshouser BA, Nickerson JP, Wall CJ, Shutter LA, Osterdock RJ, Haacke EM, Kido DK (2004) Dif use axonal injury in children: clinical correlation with hemorrhagic lesions. Ann Neurol 56:36-50.

Wang H, Duan G, Zhang J, Zhou DB (1998) Clinical studies on dif use axonal injury in patients with severe closed head injury. Chin Med J (Engl) 11:59-62.

You JS, Kim SW, Lee HS, Chung SP (2010) Use of dif usion weighted MRI in the emergency department for unconscious trauma patients with negative brain CT. Emerg Med J 27:131-132.

Copyedited by Patel B, Maxwell R, Wang J, Qiu Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

10.4103/1673-5374.170322 http://www.nrronline.org/

Tao JJ, Zhang WJ, Wang D, Jiang CJ, Wang H, Li W, Ji WY, Wang Q (2015) Susceptibility weighted imaging in the evaluation of hemorrhagic dif use axonal injury. Neural Regen Res 10(11):1879-1881.

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2015年11期

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2015年11期

- 中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Intracellular sorting pathways of the amyloid precursor protein provide novel neuroprotective strategies

- The role of the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway in inhibiting axonal regeneration in the central nervous system

- VEGF in the nervous system: an important target for research in neurodevelopmental and regenerative medicine

- Studying neurological disorders using induced pluripotent stem cells and optogenetics

- Ef cacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetics for neural regeneration

- Compliant semiconductor scaf olds: building blocks for advanced neural interfaces