Respiratory and Cardiac Characteristics of ICU Patients Aged 90 Years and Older: A Report of 12 Cases

Hong-min Zhang, Da-wei Liu*, Xiao-ting Wang, Yun Long, and Quan-hui Yang

1Department of Critical Care Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, 100730 Beijing, China2Department of Critical Care Medicine, Cancer Hospital and Institute, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, 100021 Beijing, China

?

Respiratory and Cardiac Characteristics of ICU Patients Aged 90 Years and Older: A Report of 12 Cases

Hong-min Zhang1, Da-wei Liu1*, Xiao-ting Wang1, Yun Long1, and Quan-hui Yang2

1Department of Critical Care Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, 100730 Beijing, China2Department of Critical Care Medicine, Cancer Hospital and Institute, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, 100021 Beijing, China

elderly patients; respiratory failure; shock; Takotsubo; diastolic heart failure

Objective To investigate the respiratory and cardiac characteristics of elderly Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients.

Methods Twelve senior ICU patients aged 90 years and older were enrolled in this study. We retrospectively collected all patients’ clinical data through medical record review. The basic demographics, primary cause for admission, the condition of respiratory and circulatory support, as well as prognosis were recorded. Shock patients and pneumonia patients were specifically analyzed in terms of clinical manifestations, laboratory variables, echocardiography, and lung ultrasound results.

Results The mean age of the included patients was 95 years with a male predominance (8 to 4, 66.7%). Regarding the reasons for admission, 6 (50.0%) patients had respiratory failure, 1 (8.3%) patient had shock, while 5 (41.7%) patients had both respiratory failure and shock. Of the 6 patients who suffered from shock, only 1 was diagnosed with distributive shock, 5 with cardiogenic shock. Of the 5 cardiogenic shock patients, 1 was diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome. The rest 4 cardiogenic shock patients were diagnosed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction died within 24 hours. Of the 4 Takotsubo patients, 1 died on day-6 and the other 3 patients were transferred to ward after heart function recovered in 1 to 2 weeks. Of the 10 pneumonia patients, 3 were diagnosed as community acquired pneumonia, and 7 as hospital acquired pneumonia. Only 3 patients were successfully weaned from ventilator. The others required long-term ventilation complicated with heart failure, mostly with diastolic heart failure. Lung ultrasound of 6 patients with diastolic dysfunction showed bilateral B-lines during spontaneous breathing trial.

Conclusions Elderly patients in shock tend to develop Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Diastolic heartdysfunction might be a major contributor to difficult weaning from ventilator in elderly patients. Bedside lung ultrasonography and echocardiography could help decide the actual cause of respiratory failure and shock more accurately and effectively.

Chin Med Sci J 2016; 31(1):37-42

ACCORDING to US population statistics, individuals aged 85 years and older make up 1.8 percent of the total population, but account for 8 percent of all hospital discharges.1As the geriatric population grows, the number of older patients who require intensive care in hospital will increase accordingly. Pneumonia and cardiovascular diseases are highly prevalent in older adults.2And they also tend to have comorbid chronic illnesses, making them more vulnerable to nosocomial complications and other adverse events. So the older patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit (ICU) need more attention, but few studies have been focused on this subject. We therefore present 12 ICU patients who were 90 years and older with newly onset of shock or respiratory failure, trying to figure out the respiratory and cardiac characteristics of this special cohort of patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Seventeen patients aged 90 years and older were admitted to the Department of Critical Care Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital from August 2012 to August 2013. Five patients were excluded, including three who only had selective operation without sign of shock or respiratory failure and two in obvious terminal stage. We retrospectively collected all patients’ clinical data through reviewing medical record files. The basic demographics as well as clinical and laboratory variables were analyzed. Bedside ultrasound records were carefully reviewed. We gave special attention to the lung ultrasonography and echocardiography reports upon admission to define the possible etiology of respiratory and/or circulatory failure and at day 7 after admission when their conditions were relatively stable.

RESULTS

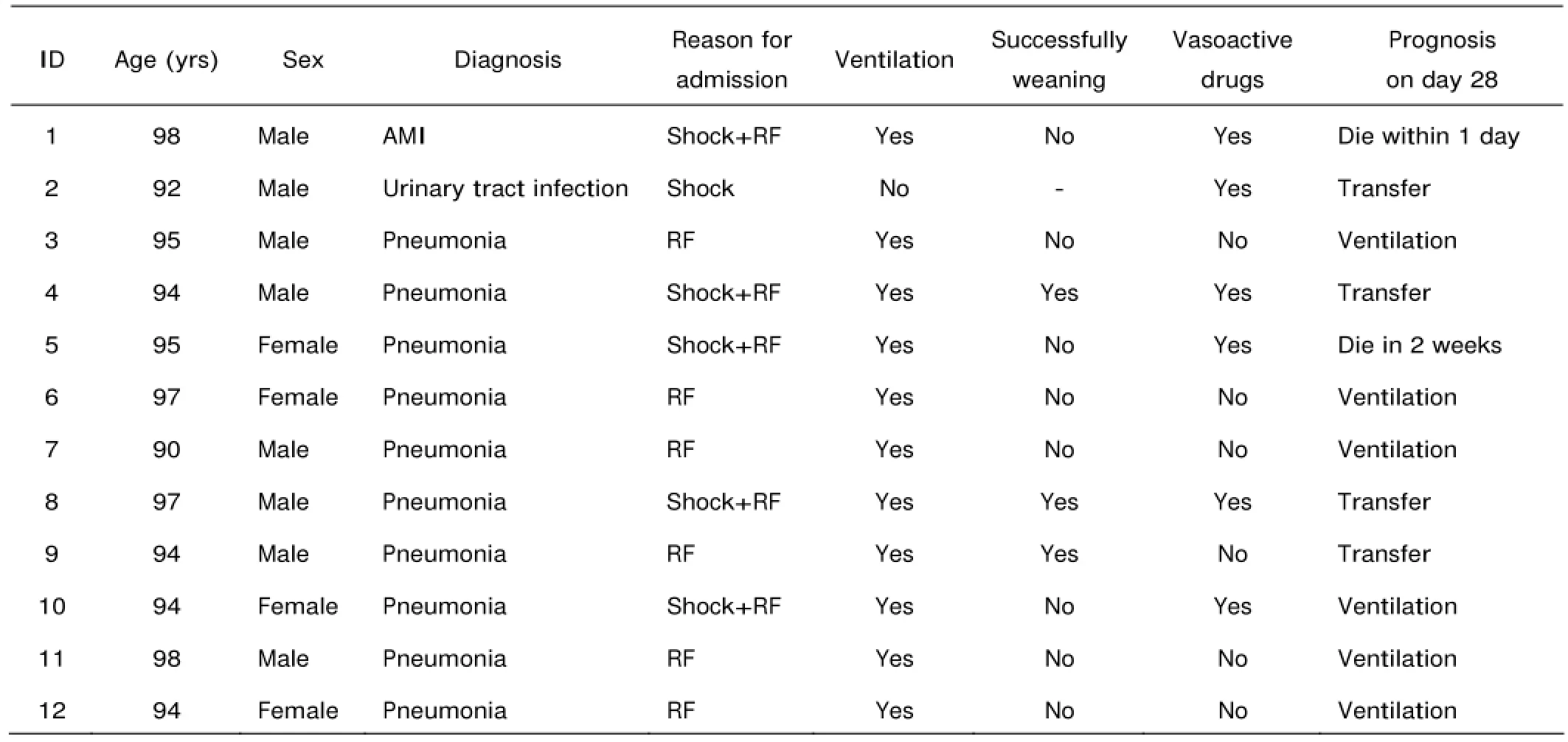

Clinical data of the 12 enrolled patients are listed in Table 1. The mean age of the included patients was 95 (range, 90-98) years with a male predominance (8 to 4, 66.7%). Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was 24±9. The major comorbid conditions included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=1, 8.3%), hypertension (n=7, 58.3%), coronary artery disease (n=6, 50.0%), diabetes mellitus (n=5, 41.7%), chronic kidney dysfunction (n=5, 41.7%), and cerebral infarction (n=1, 8.3%). Regarding the reasons for admission, 6 (50.0%) patients had respiratory failure, 1 (8.3%) patient had shock, while 5 (41.7%) patients had both respiratory failure and shock. The primary cause for respiratory failure and/or shock was pneumonia (n=10), acute myocardial infarction (n=1), and urinary tract infection (n=1). In the 12 patients, 11 required mechanical ventilation and only 3 patients were successfully weaned from the ventilator. Six patients needed vasoactive drugs to maintain the hemodynamic stability. The prognosis on day 28 was death (n=2), transfer to ward (n=4), and long-term ventilatory support (n=6).

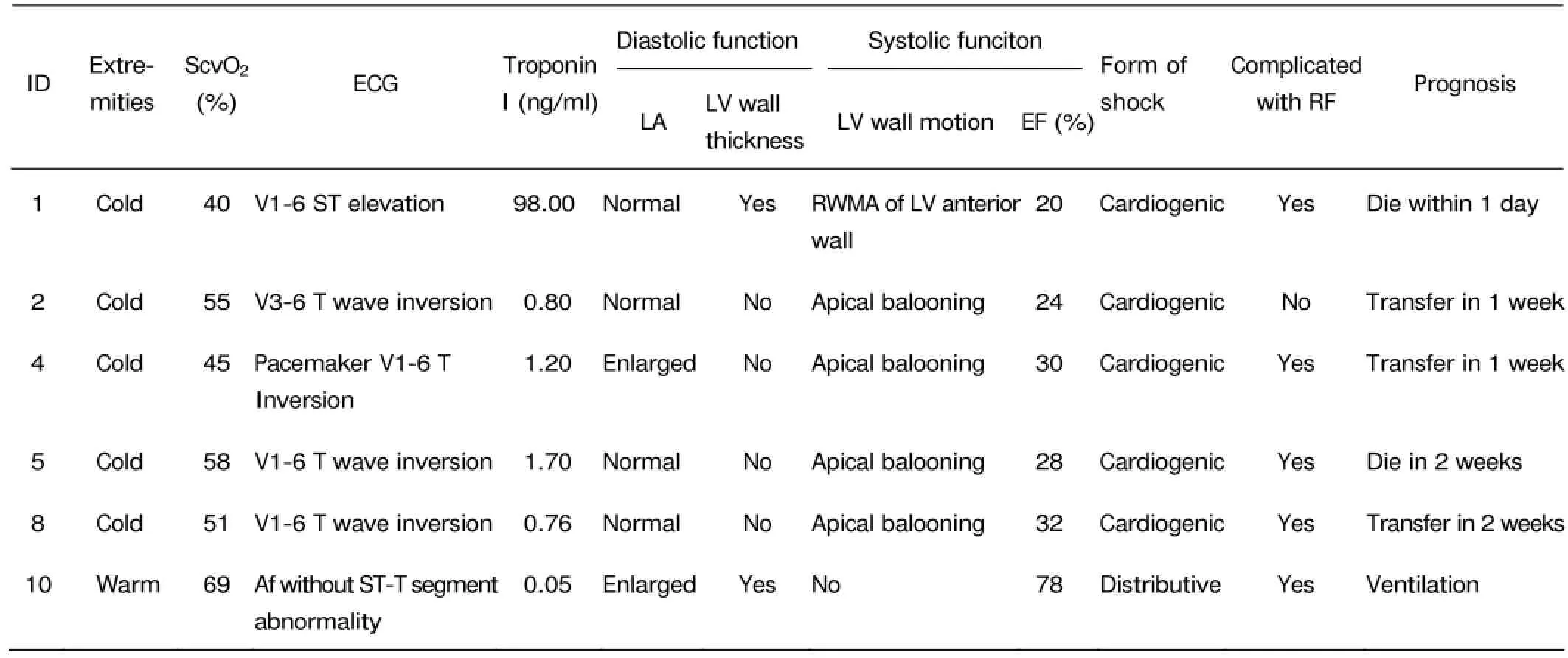

Clinical data of 6 shock patients are shown in Table 2. Of the 6 patients who were shock, only 1 was diagnosed with distributive shock exhibiting warm extremities and high central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) level, and 5 with cardiogenic shock. Of the 5 cardiogenic shock patients, 1 presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) on electrocardiogram, regional wall motion abnormality on echocardiography, and elevated serum troponin I concentration (98.00 ng/ml). The signs of the rest 4 cardiogenic shock patients were echocardiographic apical ballooning and T-wave inversion in the precordial leads on ECG and a slight increase of troponin I (the highest level 1.70 ng/ml), which were signs consistent with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient with STEMI died within 24 hours. Of the 4 Takotsubo patients, 1 died on day-6 and the other 3 patients were transferred to ward after their heart function recovered in 1 to 2 weeks.

Of the 10 pneumonia patients, whose clinical pneumonia infection score ranged from 6 to 8, 3 were diagnosed as community acquired pneumonia, and 7 were diagnosed as hospital acquired pneumonia. Only 3 patients were successfully weaned from ventilator. The remaining 7 patients required long-term ventilation complicated with heart failure, mostly with diastolic heart failure characterized by atrial fibrillation, enlarged left atrium, normal ejection fraction, and a higher E/E’, which is a precise reflection of left atrial pressure. The 6 patients with diastolic dysfunction also showed bilateral B-lines on lung ultrasound during spontaneous breathing trial. (Table 3)

Table 1. Clinical data of the 12 patients enrolled

Table 2. Clinical data of 6 shock patients on admission

DISCUSSION

With the accelation of aging population, older, disabled patients in ICU are considered as a new challenge that doctors need more proficiency in preserving their already impaired organ function and evaluating the probability of the patient weaned from ventilator and/or transferred from ICU. But few studies have involved ICU patients aged 90 years and older, therefore, we investigated the clinical characteristics of a group of such patients, and hope that the results will improve the management of such patients in the future. We found much higher prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and diastolic heart failure among these patients.

Bedside echocardiography and lung ultrasound help intensivists to clarify the most likely cause of shock and respiratory failure more easily, and to some extent help optimize the outcome.3,4We found bedside ultrasonography was a useful imaging technique to diagnose and treattreat respiratory and cardiac lesions of elderly patients. The ultrasonic examinations were performed by qualified physician to accommodate the clinical need, such as shock differentiation, determining the reason for weaning failure, and the results were carefully recorded.

We found that infection, especially pulmonary infection accounts for the major reason for patients 90 years of age and older to develop respiratory failure and/or shock. As it is known to all that sepsis, a form of distributive shock, which is defined as infection plus systemic inflammatory response syndrome, can lead to septic shock. And sepsis related heart depression is also commonly recognized, perhaps just in different nomenclature such as septic cardiomyopathy, sepsis-associated myocardial dysfunction, or myocardial depression, and so on.5-7This kind of heart dysfunction is characterized by biventricular impairment of intrinsic myocardial contractility. Usually the entire left ventricle is significantly hypokinetic with ventricular cavity dilation and ejection fraction reduced to around 30%.8But to our surprise, we found Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, not septic cardiomyopathy was the most prevalent condition in this group of patients.

Table 3. Clinical data of 10 pneumonia patients on day 7 or at the day of dismissal

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, is generally characterized by reversible systolic dysfunction of the apical and/or mid segments of the left ventricle with presentations mimicking myocardial infarction, but in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease.9Exclusion of coronary artery disease by coronary angiography is usually required for the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.10But in ICU settings, the following may indicates stress cardiomyopathy rather than acute coronary syndrome. Severe acute left ventricular dysfunction without a significant serum troponin and creatine kinase-MB elevation; symmetrical mid and apical regional wall motion abnormalities on echocardiography; repeated echocardiography from a few days to weeks confirming complete recovery of left ventricular function.11

A systematic review showed that in-hospital mortality rates of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy ranged from 0 to 8%.12Most of the patients will survive the acute episode and recover normal left ventricular function within one to four weeks.13Older patients developing Takotsubo cardiomyopathy are more likely to develop heart failure. A study on Takotsubo patients found that the following two variables werethe risk factors for acute heart failure: age >70 years and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%.14The findings in our study were consistent with these research results.

Takotsubo patients who are in shock usually be divided into two categories depending on if left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present. Patients without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction who are in shock due to pump dysfunction can be treated cautiously with inotropes. While those with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction should not be treated with inotropic agents, because they can worsen the degree of obstruction.15In the present study, all the 4 Takotsubo patients were treated with vasoactive drugs after fluid optimization to maintain the blood pressure.

Diastolic heart failure can be diagnosed by the presence of symptoms and signs of heart failure in a patient with a normal LVEF according to the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.16Echocardiography is the most practical clinical approach for evaluating left ventricular diastolic function given enough evidence supporting its use as well as its safety and portability. Echocardiography can recognize the abnormal myocardial relaxation and increased left ventricular filling pressures. Other signs for diastolic dysfunction include the increase in thickness of the left ventricular wall and enlargement of the left atrium.17A decrease in early mitral annulus velocity (E’) is one of the earliest markers for diastolic dysfunction, the ratio between E and E’ (E/E’) correlates well with left ventricular filling pressure or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and its accuracy has been tested in a variety of clinical settings.17-19An E/E’ ratio below 8 is often associated with normal filling pressures and the ratio being more than 12 but less than 15 is associated with elevated filling pressures. The ratio was clinically useful to evaluate the left ventricular function of patients with tachycardia and with atrial fibrillation.20,21

Ultrasonograpy is a useful tool to make differential diagnosis of respiratory failure, particularly in differentiating cardiogenic from non-cardiogenic etiologies.22,23Our results demonstrated that the patients who were unable to wean from ventilator presenting with bilateral B-lines after spontaneous breathing trial. The echocardiographic findings confirmed the diagnosis of diastolic heart dysfunction based on enlarged left atrium, preserved ejection fraction, and a much higher E/E’. Positive fluid balance, another etiology of acute pulmonary edema, was not a problem in the ventilator-dependent patients as reevaluating volume status was a prerequisite in our unit before the diagnosis of difficult-to-wean. These findings gave a strong indication about a cardiac origin of respiratory failure in these patients.

In conclusion, elderly patients in shock tend to develop Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Diastolic heart dysfunction might be a major contributor to weaning failure in elderly patients. Bedside lung ultrasonography and echocardiography could help decide the actual cause of respiratory failure and shock more accurately and effectively.

REFERENCES

1. Wier L, Pfuntner A, Steiner C. Hospital utilization among oldest adults, 2008: statistical brief #103. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (US); 2006-2010 Dec.

2. Marengoni A, Winblad B, Karp A, et al. Prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly population in Sweden. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 1198-200.

3. Subramaniam B, Talmor D. Echocardiography for management of hypotension in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007; 35:S401-S7.

4. Cardinale L, Volpicelli G, Binello F, et al. Clinical application of lung ultrasound in patients with acute dyspnoea: differential diagnosis between cardiogenic and pulmonary causes. Radiol Med 2009; 114:1053-64.

5. Hunter JD, Doddi M. Sepsis and the heart. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104:3-11.

6. Maeder M, Fehr T, Rickli H, et al. Sepsis-associated myocardial dysfunction: diagnostic and prognostic impact of cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides. Chest 2006; 129:1349-66.

7. Bonnemeier H, Weidtmann B. Mechanisms of myocardial depression in sepsis: association of L-type calcium current density and ventricular repolarization duration. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:724-5.

8. Marcelino PA, Marum SM, Fernandes AP, et al. Routine transthoracic echocardiography in a general intensive care unit: an 18 month survey in 704 patients. Eur J Intern Med 2009; 20:e37-e42.

9. Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation 2008; 118:2754-62.

10. Bybee KA, Prasad A. Stress-related cardiomyopathy syndromes. Circulation 2008; 118:397-409.

11. Chockalingam A, Mehra A, Dorairajan S, et al. Acute left ventricular dysfunction in the critically ill. Chest 2010; 138:198-207.

12. Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review:transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:858-65.

13. Kurisu S, Sato H, Kawagoe T, et al. Takotsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction with ST-segment elevation: a novel cardiac syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2002; 143:448-55.

14. Madhavan M, Rihal CS, Lerman A, et al. Acute heart failure in apical ballooning syndrome (TakoTsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): clinical correlates and Mayo Clinic risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:1400-3.

15. Villareal RP, Achari A, Wilansky S, et al. Anteroapical stunning and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Mayo Clin Proc 2001; 76:79-83.

16. Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to revise the 1995 guidelines for the evaluation and management of heart failure. Circulation 2001; 104:2996-3007.

17. Oh JK, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Assessment of diastolic function and diastolic heart failure. Echo Manual. 3rd ed. Lippincott WIlliams & Wilkins 2006. p. 122-42.

18. Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009; 22: 107-33.

19. Dokainish H, Zoghbi WA, Lakkis NM, et al. Optimal noninvasive assessment of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparison of tissue Doppler echocardiography and B-type natriuretic peptide in patients with pulmonary artery catheters. Circulation 2004; 109:2432-9.

20. Nagueh SF, Mikati I, Kopelen HA, et al. Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressure in sinus tachycardia. A new application of tissue doppler imaging. Circulation 1998; 98:1644-50.

21. Sohn DW, Song JM, Zo JH, et al. Mitral annulus velocity in the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function in atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1999; 12:927-31.

22. Copetti R, Soldati G, Copetti P. Chest sonography: a useful tool to differentiate acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema from acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2008; 6:16.

23. Via G, Storti E, Gulati G, et al. Lung ultrasound in the ICU: from diagnostic instrument to respiratory monitoring tool. Minerva Anestesiol 2012; 2:1282-96.

for publication June 4, 2015.

*Corresponding author Tel: 86-10-69152300, E-mail: dwliu@medmail.com.cn

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Resulting from a Troponin I Type 3 Mutation in a Chinese Family

- Association Between Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Gene Polymorphisms and Bone Phenotypes and Response to Alendronate Treatment in Chinese Osteoporotic Women△

- Positive Rate of Different Hepatitis B Virus Serological Markers in Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a General Tertiary Hospital in Beijing△

- Establish Albumin-creatinine Ratio Reference Value of Adults in the Rural Area of Hebei Province△

- Percutaneous Removal of Benign Breast Lesions with an Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted System: Influence Factors in the Hematoma Formation△

- Life-threatening Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Haemorrhage: Role of Multidetector CT-angiography for the Emergency Management