Hospitalization for Congenital Heart Disease in Beijing: Patient Characteristics and Temporal Trends

Yafei Cui, Dong Zhao, Jiayi Sun, Miao Wang, Yinglong Liu and Jing Liu

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a major form of birth defects and is the main cause of infant death [1,2]. The incidence of CHD is reported to be about 9 per 1000 live births worldwide, with an increasing trend in recent decades [3]. Similar trends were also found in China and in Bei jing [4]. Meanwhile, CHD mortality has been declining [5]. The increasing incidence of CHD and decreasing CHD mortality could lead to more people surviving with CHD and in need of more hospital care. Studies have shown that the number of CHD hospitalizations has been increasing in recent decades [6]. However, recent patterns and trends in CHD hospitalization at the national or regional level remain unknown in China.Previous data for CHD hospitalization in Beijing were limited to databases from pediatric departments of selected hospitals [7]. Although that study helped to identify CHD as a major cause of hospitalization and the leading cause of in-hospital death for children, the results were not generalizable to other hospitals and could not capture the characteristics of CHD as a whole. We therefore assessed the burden of hospital care among patients with CHD in Beijing by examining recent characteristics and temporal trends in CHD hospitalization from 2007 to 2011 using an unselected city-level administrative database.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

The Beijing Hospital Discharge Information System(HDIS) contains discharge data from all secondary and tertiary nonmilitary hospitals in Beijing.Hospital discharges of patients with CHD admitted from 2007 to 2011 were identified on the basis of the primary discharge diagnosis with International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10th revision codes of Q20–Q26 [5]. The severity of CHD was further classified into nonsevere and severe CHD, among which severe CHD was defined by the presence of the primary diagnosis with ICD-10 codes for lesions,as outlined previously [8], including dextrotransposition of the great vessels, tetralogy of Fallot, tricuspid valve atresia, hypoplastic left-sided heart syndrome,single ventricle, common truncus, interrupted aortic arch, pulmonary atresia without ventricular septal defect, double outlet right ventricle, endocardial cushion defect, total anomalous pulmonary venous return, and Epstein anomaly. In the case of other hospitalizations without the primary diagnosis of severe CHD, the hospitalizations were considered as being for nonsevere CHD. Patients who were discharged and then readmitted on the same day (including transferred patients) were linked and considered as a single continuous episode of care (n=164). Audit for the quality of data in the HDIS is conducted annually by the Beijing Public Health Information Center and Beijing Municipal Health Bureau, and the concordance between ICD code–based primary diagnoses in the HDIS and diagnoses in original hospital records is more than 95%. The age-specific annual population of permanent residents in Beijing for each year of interest was obtained from the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. The study was approved by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission. No other ethics approval is necessary or required in China for this type of study using existing and anonymous data from of ficial agencies.

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of patients hospitalized for CHD were described in aggregate and by year, in terms of age (<1, 1–4, 5–17, and ≥18 years of age), sex,ethnicity, residency, severity of CHD, and level of hospital (cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals, other tertiary hospitals, secondary hospitals). Age 18 years was used as the threshold for adulthood, because patients aged 18 years or older are no longer under pediatric care in China. Changes in the proportions of these categorical variables between 2007 and 2011 were examined by a chi-square test for trend.The hospitalization rate for CHD was calculated as the number of CHD hospitalizations among permanent residents in Beijing divided by the number of permanent residents in that year. Hospitalization rates were calculated only for per manent residents because annual numbers for the nonpermanent residents in Beijing are not available. All rates were reported per 100,000 persons. The age-standardized rate was calculated according to the 2010 census population of Beijing. Trends in total hospitalization rates over the study period were calculated by Poisson regression after adjustment for age and/or sex as needed. SA S version 9.2 (SAS Institute,Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized for CHD in Beijing

There were 53,064 CHD hospital admissions at 105 hospitals in Beijing between 2007 and 2011.

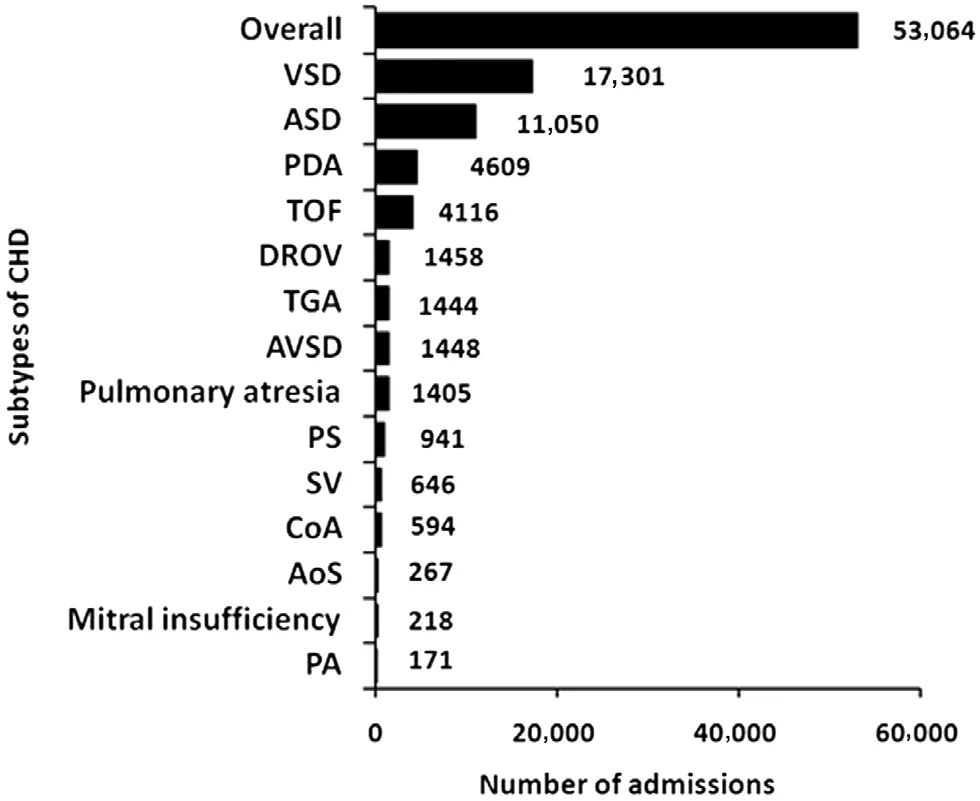

Figure 1 Number of Hospitalizations for Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) in Beijing, 2007 to 2011.

Among the 105 hospitals, there were two cardiacspecific tertiary hospitals, 42 other tertiary hospitals, and 61 secondary hospitals. In total, 50.5% of the hospitalizations were for children you nger than 5 years, 30.0% were for adults (≥18 years), 49.9%were for females, 94.0% were for people of Han ethnicity, and 13.1% were for permanent Beijing residents. Overall, 18.5% of the patients had severe CHD, and 81.3% were admitted to cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals. The top four CHD lesions identified by primary diagnosis were ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus,and tetr alogy of Fallot (Figure 1).

Over the 5 years, the number of CHD admissions increased by 32.9%, from 9257 in 2007 to 12,300 in 2011. As shown in Table 1, the largest relative increase in 2011 compared with 2007 was found in children aged 1–4 years among both permanent Beijing residents and nonpermanent residents. Over the study period, the proportions of minorities and severe CHD, and the proportions of hospitalizations in cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals increased among permanent and nonpermanent residents,whereas the increasing trend for severe CHD did not reach statistical significance among permanent residents.

Hospitalization Rates for CHD in Beijing

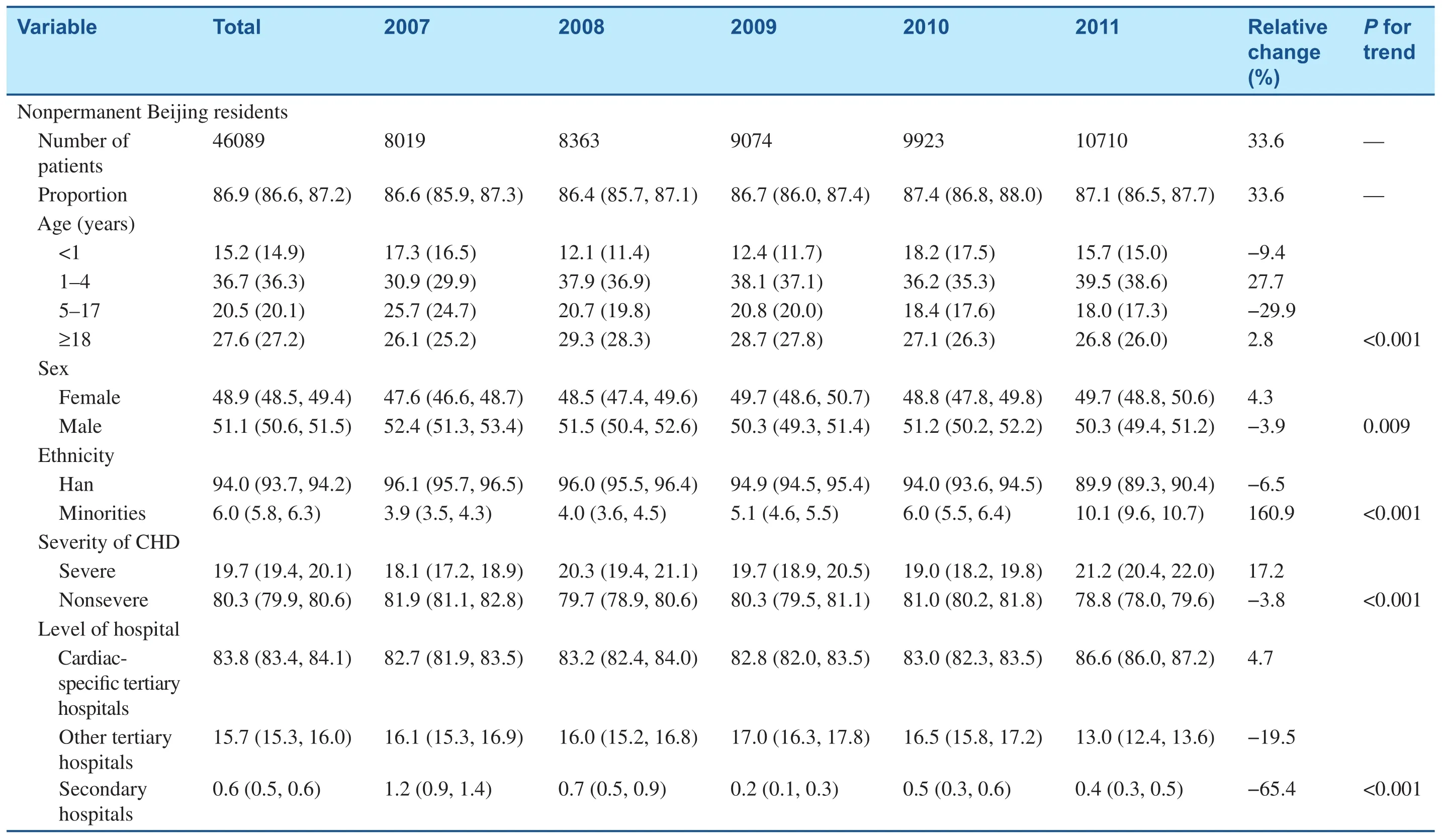

The aggregate rate of CHD hospitalization was 11.2 per 100,000 persons during the period from 2007 to 2011. Females had a higher rate than males (12.8 per 100,000 in females and 9.7 per 100,000 in males,P< 0.001). This difference persisted after age standardization (16.8 per 100,000 in females and 13.2 per 100,000 in males,P< 0.001). However, males had a significantly higher hospitalization rate among infants, which was mainly attributable to severe CHD (Figure 2). Among all age groups, infants had the highest hospitalization rate for both severe CHD and nonsevere CHD, and the rates decreased with increasing age.

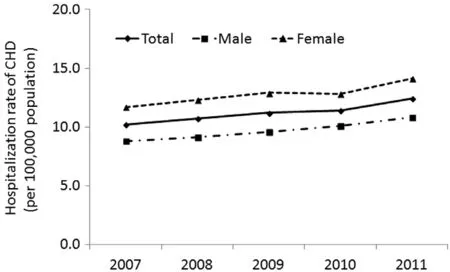

Over time, the crude hospitalization rate rose from 10.2 per 100,000 persons in 2007 to 12.4 per 100,000 persons in 2011, representing a 21.6%increase (Table 2 and Figure 3). The trend was statistically significant after adjustment for age and sex(P= 0.009). Similar trends were found for males and females after adjustment for age. However,the trends differed among patients of different age and severity. There was a decreasing trend among infants, mainly due to the decline in 2011. The rates halved in 2011 for both nonsevere CHD and severe CHD compared with the rates in 2010. Increasing trends were noticed in children aged 1–4 years and adults for nonsevere CHD across the study period,while the trends for severe CHD were not signifi -cant among different groups.

Comments

By using a large database of a unselected hospitalized patient population with CHD at the city level,we demonstrated the most recent patient characteristics and temporal trends in CHD hospitalization in Beijing. The hospitalization rate for CHD increased significantly in the overall population of Beijing from 2007 to 2011, whereas diverse trends were noticed in different patient groups. The hospitalization rate decreased markedly among infants, while the rate for nonsevere CHD increased among adults.Our study revealed an increasing hospitalization burden of CHD in Beijing between 2007 and 2011,demonstrated by both the number of hospitalizations for CHD in Beijing and the hospitalization rate among permanent residents. There are severalpossible reasons for this increase. One explanation involves the rise in the incidence rate of CHD. It has been reported that the CHD incidence increased from 0.57% in 1997 to 4.35% in 2006 in Beijing [4], which in turn could be partially explained by increases in risk factors for CHD.Previous studies shown that advanced maternal age and diabetes mellitus in pregnancy were more commonly seen in recent years [9, 10], which might increase the risk of CHD. Additionally,because of the improvement in CHD treatment,the number of adult patients with CHD increased,which might give rise to an increased risk of their offspring being born with congenital anomalies[11, 12]. Another explanation involves the rate of detection of CHD. Developments in diagnostic methods and screening modalities resulted in CHD being diagnosed in more patients, especially for patients with nonsevere CHD, which may mendaciously increase the incidence of CHD and further cause an increase of the hospitalization rate [13].Moreover, the aging population with a greater risk of complications could partly explain but could not be the main reason for the increasing hospitalization burden of CHD, because the hospitalization rate for overall CHD still increased significantly from 14.4 per 100,000 persons in 2007 to 15.7 per 100,000 persons in 2011 after age standardization.

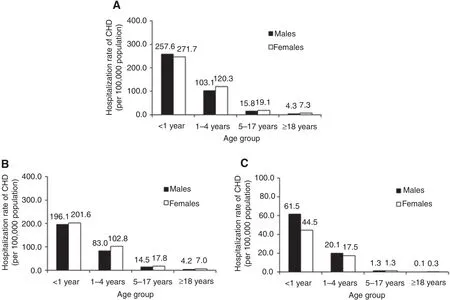

Table 1(continued)

Figure 2 Hospitalization Rates for Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) by Age, Sex, and Severity in Beijing, 2007 to 2011.(A) Overall CHD, (B) non severe CHD and (C) severe CHD.

The increased number of hospitalizations over the years reflects a larger number of patients with CHD in need of health care services. As demonstrated by our study, adult hospitalizations accounted for 30.0% of CHD hospital admissions, and the hospitalization rate for nonsevere CHD increased significantly in adults, leading to further demands for adult CHD care. National mortality data from the United States have shown that among patients who survived the first year of life, more than three-quarters of deaths due to CHD occurred during adulthood [5]. It is estimated that at least half of all adult CHD patients will require care by a physician specializing in CHD, and general adult cardiologists and hospitals may not be able to meet this challenge[14].

Another notable finding of our study was the significant fall in the CHD hospitalization rate among infants, mainly associated with the drop in 2011.This finding was similar to the decreasing trend of incidence among permanent residents of Beijing from 2010 found by Liu et al. [15]. As shown by data from the Beijing HDIS, the annual increase in the number of hospitalized medical abortions from2010 to 2011 was more than threefold the annual increase in previous years [16–19]. The increasing number of medical abortions and the decreasing rate of CHD hospitalization in 2011 may be partly associated with the prenatal CHD screening that has been widely performed in Beijing since 2010. It has been reported that among fetuses with diagnosed CHD in Beijing, the pregnancy was terminated in 84.8% of cases, and even for nonsevere CHD, such as ventricular septal defect, the termination rate was more than 80% [20]. Studies in Western countries also found that prenatal screening affected the prevalence and types of CHD seen at term, because on average 43% of affected pregnancies were terminated [21, 22]. The termination rate in Beijing was higher than the rates reported in Western populations, possibly due to the one-child policy in China and the financial burden for the treatment of CHD[20]. It could be expected that the hospitalization burden for CHD among permanent residents of Beijing would decline by a large margin among children if the low rates in infants persist.

Table 2Hospitalization Rates for Congenital Heart Disease (Per 100,000 Persons) in Beijing by Age, Sex, and Severity of Congenital Heart Disease, 2007 to 2011.

Figure 3 Trends of Hospitalization Rates for Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) in Beijing, 2007 to 2011.

In addition to the changing CHD hospitalization rates among permanent residents of Beijing,our study noted an aggregated hospital care for CHD. Firstly, the hospitalizations aggregated to the cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals. Overall, more than 80% of hospitalizations were in two large cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals in Beijing, with an increasing proportion from 79.6% in 2007 to 84.1% in 2011. Studies in developed countries have shown that patients who underwent surgical procedures at high-volume centers had better outcomes[23, 24]. Our previous study also demonstrated that the overall in-hospital case-fatality rate of CHD between 2007 and 2011 was lower in patients admitted to cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals compared with non–cardiac-specific hospital (1.01 vs. 3.67%,P< 0.001) [25]. Although these data indicate concentrating CHD services in high-volume hospitals may have favorable effects on patient outcomes,policymakers and health care providers should consider keeping hospital volumes reasonable to ensure quality of care [26]. Secondly, we found that CHD patients from other regions of China are aggregating to Beijing. On average, 86.9% of the hospital admissions were accounted for by nonpermanent residents ( i.e., migrants or people who purposely came from other provinces). Patients in China are free to seek hospital care for CHD in two of the best Chinese cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals located in Beijing, without the mandatory general practitioner gatekeeping system. Although data on the annual population of nonpermanent residents were not available, there was a larger relative increase in the number of nonpermanent Beijing residents with CHD compared with permanent residents.These findings provide important information to help guide decisions about the optimal allocation of inpatient resources for CHD, and to highlight areas in health care requiring further progress.

The major limitation of this study related to the quality of the administrative database used. CHD hospitalizations were identified via a diagnostic code, and the findings need to be interpreted with caution because of concerns about the accuracy of the coding. Although the annual audit for the data quality of the HDIS suggests a coding accuracy of greater than 95%, a formal validation study is needed. Second, the current information system did not cover military hospitals. However, the number of CHD patients admitted to military hospitals is likely to be small and stable, and their exclusion was therefore unlikely to alter the identified trends,although there may have been some underestimation of hospitalization rates.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a steadily increasing rate of CHD hospitalization in the overall population of Beijing from 2007 to 2011, but not all patient groups had the same trend. The hospitalization rate decreased among infants, while the rate for nonsevere CHD increased significantly among adults.In addition, there was an aggregated hospital care for CHD, including the hospitalizations aggregating to the cardiac-specific tertiary hospitals and the patients from other regions aggregated to Beijing.The changing patterns of demographic and clinical characteristics of hospitalized CHD patients provide essential information to guide the future allocation of health resources.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (contract no.Z111100074911001) and the Capital Health Research and Special Development (contract no. 2016-1-1051).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Dastgiri S, Stone DH, Le-Ha C,Gilmour WH. Prevalence and secular trend of congenital anomalies in Glasgow, UK.Arch Dis Child 2002;86:257–63.

2. Rosano A, Botto LD, Botting B,Mastroiacovo P. Infant mortality and congenital anomalies from 1950 to 1994: an international perspective. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:660–6.

3. van der Linde D, Konings EE,Slager MA, Witsenburg M,Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJ, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2241–7.

4. Liu KB, Pan Y, Lin HM, Xu HY,Ding H. Analysis of the trend of perinatal congenital heart disease in Beijing area over 10 year period. Chin J Birth Health Hered 2008;16:100–6. [in Chinese]

5. Gilboa SM, Salemi JL, Nembhard WN, Fixler DE, Correa A. Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006.Circulation 2010;122:2254–63.

6. Report of the British Cardiac Society Working Party. Grown-up congenital heart (GUCH) disease:current needs and provision of service for adolescents and adults with congenital heart disease in the UK. Heart 2002;88(Suppl 1):i1–14.

7. Xia L, Zhong-dong D, Zhong-shu Z, Jian K, Yue-song P. The trends of diseases and cause-specific death in hospitalized children in the hospitals of urban Beijing from 2003 to 2009. Chin J Pract Pediatr 2013;28:537–9. [in Chinese]

8. Pradat P, Francannet C, Harris JA, Robert E. The epidemiology of cardiovascular defects, part I:a study based on data from three large registries of congenital malformations.Pediatr Cardiol 2003;24:195–221.

9. Chang Y, Chen X, Cui H, Zhang Z,Cheng L. Follow-up of postpartum women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Diabetes Res Clin Pr 2014;106:236–40.

10. Shan X, Chen F, Wang W, Zhao J,Teng Y, Wu M, et al.Secular trends of low birthweight and macrosomia and related maternal factors in Beijing, China: a longitudinal trend analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:105.

11. Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu-Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L.Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution.Circulation 2007;115:163–72.

12. Burn J, Brennan P, Little J,Holloway S, Coffey R, Somerville J, et al. Recurrence risks in offspring of adults with major heart defects: results from first cohort of British collaborative study. Lancet 1998;351:311–6.

13. Chen XH, Yuan X, Yan SJ, Zhang WX, Zhu XN. Analysis of the trend of neonate congenital heart disease in Beijing area over 5 year period. Chin J Birth Health Hered 2011;19:101–7. [in Chinese]

14. Gurvitz MZ, Chang RK, Ramos FJ, Allada V, Child JS, Klitzner TS. Variations in adult congenital heart disease training in adult and pediatric cardiology fellowship programs.J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:893–8.

15. Liu KB, Zhang W, Xu HY, Pan Y.The analysis of monitoring data for congenital heart disease in Beijing, 2007–2012. Chin J Birth Health Hered 2013;21:127–42. [in Chinese]

16. The Public Health Information Center of Beijing. The number of hospitalizations in governmentrun hospital stratified by subgroup of disease type and age (total). In:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau,editor. Beijing annual statistical report on health in 2008. Beijing:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau;2008. pp. 588–95. [in Chinese]

17. The Public Health Information Center of Beijing. The number of hospitalizations in governmentrun hospital stratified by subgroup of disease type and age (total). In:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau,editor. Beijing annual statistical report on health in 2009. Beijing:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau;2009. pp. 572–9. [in Chinese]

18. The Public Health Information Center of Beijing. The number of hospitalizations in governmentrun hospital stratified by subgroup of disease type and age (total). In:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau,editor. Beijing annual statistical report on health in 2010. Beijing:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau;2010. pp. 556–62. [in Chinese]

19. The Public Health Information Center of Beijing. The number of hospitalizations in partial medical institutions stratified by subgroup of disease type and age (total). In:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau,editor. Beijing annual statistical report on health in 2011. Beijing:Beijing Municipal Health Bureau;2011. pp. 556–62. [in Chinese]

20. Yang XY, Li XF, Lu XD, Liu YL.Incidence of congenital heart disease in Beijing, China. Chinese Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1128–32.

21. Bull C. Current and potential impact of fetal diagnosis on prevalence and spectrum of serious congenital heart disease at term in the UK. British Paediatric Cardiac Association. Lancet 1999;354:1242–7.

22. Germanakis I, Sifakis S. The impact of fetal echocardiography on the prevalence of liveborn congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2006;27:465–72.

23. Hannan EL, Racz M, Kavey RE,Quaegebeur JM, Williams R.Pediatric cardiac surgery: the effect of hospital and surgeon volume on in-hospital mortality. Pediatrics 1998;101:963–9.

24. Jenkins KJ, Newburger JW, Lock JE, Davis RB, Coffman GA,Iezzoni LI. In-hospital mortality for surgical repair of congenital heart defects: preliminary observations of variation by hospital caseload.Pediatrics 1995;95:323–30.

25. Cui YF, Zhao D, Wang W,Xie XQ, Guo MN, Wang M, et al.In-hospital case-fatality rate among patients admitted for congenital heart disease in Beijing during 2007–2011. J Cardiovasc Pulm Dis 2014;33:17–22. [in Chinese]

26. Diller GP, Kempny A, Piorkowski A, Grubler M, Swan L,Baumgartner H, et al. Choice and competition between adult congenital heart disease centers:evidence of considerable geographical disparities and association with clinical or academic results. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:285–91.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年1期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2017年1期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Role of Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents and Bypass Grafting in Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- The Effect of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation on Functional Capacity,Behavior, and Risk Factors in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome in China

- Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation:Where Are We?

- Antithrombotic Therapy: Focus on the Elderly

- Inherited Cardiomyopathies: Genetics and Clinical Genetic Testing

- Depression, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease in Chinese: A Review for a Bigger Picture