The Treatment of Other Cultures in Transcultural Writing—A Cognitive Semiotic Re fl ection

Labao Wang

Soochow University, China

The Treatment of Other Cultures in Transcultural Writing—A Cognitive Semiotic Re fl ection

Labao Wang

Soochow University, China

Transcultural literary studies as advocated by Italo-Australian critic Arianna Dagnino claims to investigate writers who live transnational lives and write out of a border-crossing and transcendent sensibility. But, in arguing for indeterminacy and fuzziness in transcultural novels, it fails to explain how specifically different cultures should be dealt with in this type of writing. In this essay, I draw on Per Aage Brandt’s cognitive semiotic definition of cultural “sedimentation” as opposed to Raymond Williams’ “analysis of culture” to help with a close reading of two Australian travel novels of the 20th century, i.e. Margaret Jones’The Confucius Enigmaand Nicholas Jose’sAvenue of Eternal Peace, with special attention to how the two books handle Chinese culture. Such a reading reveals that, while both novels are set in China, the former remains satisfied with minimum cultural representation, and the latter mainly focuses on certain areas of contemporary Chinese culture instead of others. AlthoughAvenue of Eternal Peacedoes dig beyond the “iconic meanings” of the Chinese culture to reveal authorial knowledge of its “symbolic meanings”, the novel devotes too much of itself to the overwhelmingly “negative semiosis” of China, reflecting a complacent attitude on the part of the protagonist/narrator/author towards Chinese culture. For this reason, neither novel meets Dagnino’s criteria for transcultural writing. And the two novels start us thinking about Dagnino’s theorization of transcultural writing because her emphasis on “transcending” only implies an aloofness and detachment. Brandt’s definition of culture as sedimented symbolic meanings teaches us that genuine transcultural writers should perhaps be prepared not just to know and understand and stay at a distance from other cultures but to engage and heartily share and even partake of their sedimented symbolic meanings at all levels and learn to feel the same way about them as their native members. This is true of the third world diasporic/migrant writers living and writing in the first and second worlds that Dagnino’s theory of transcultural writing remains focused on, but even more of the first and second worlds writing about their transcultural experiences in the third world countries. I argue that part of the intention ofDagnino’s transcultural literary studies is to move beyond postcolonialism’s concern over cultural unevenness and asymmetry, but this study proves that postcolonialism is not and should not be taken as completely over.

transcultural literary studies, transcultural writing, culture,The Confucius Enigma,Avenue of Eternal Peace, transcending, sharing

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 20th century, literary studies in the West have seen a whole contingent of paradigm shifts, the latest being towards transcultural literary studies. In 2015, Italo-Australian critic Arianna Dagnino from Adelaide published her new bookTranscultural Writers and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility, in which she argued that the age of globalization is giving birth to growing numbers of “culturally mobile writers or ‘transcultural writers’ with an emerging transcultural sensibility” (2015, p. 1). Dagnino sees her work in the context of transcultural literary studies, and she intends to “explore the identity and cultural metamorphoses inherent in the transcultural process of ‘transpatriation’ that may be triggered by moving—physically, virtually, or imaginatively—outside one’s cultural and homeland or geographical borders” (2015, p. 2). Dagnino argues that the AUTHORS of transcultural novels tend to live transnational lives, and they 1. set their novels in more than one country; 2. create characters coming from more than one cultural background; 3. tell a story from “a multiplicity of perspectives”; 4. use foreign words and expressions and promote a kind of blended or “fusion” idiom (p. 213). For a brief summing up of what a typical transcultural novel would be like, she quotes German anglicist Sissy Helff who says: a transcultural NOVEL has at least one of the following aspects: 1. the narrators’ lifeworld is characterized by experiences of border crossing and transnational identities; 2. the narrator and/or the narrative challenge(s) the collective identity of a particular community; 3. traditional notions of “home” are disputed (Helff, 2009, p. 83).

Dagnino’s theorization about transcultural writers reminds us of a cosmopolitan attitude towards alien cultures that one relates to what Oliver Goldsmith once referred to as the qualities of “the citizen of the world”. According to this theory, if you are a transcultural writer, you will have a “transcultural lens, ‘a(chǎn) perspective in which all cultures look decentred in relation to all other cultures, including one’s own’” (Bery & Epstein, p. 312). For exemplification, she points to Belgian-born French novelist living in the United States Marguerite Yourcenar and Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges as the 20th century forerunners. Dagnino offers a list of some 20 writers including Inez Baranay, Brian Castro, J. M. Coetzee, Edouard Glissant, Amitav Gosh, Abdulrazak Gurnah, Milton Hatoum, Alberto Manguel, Janice Kulyk Keefer, Oonya Kepadoo, Pico Iyer, Pap Khouma, Nicola Lecca, J.M.G. Le Clezio, Amin Maalouf, Michael Ondatje, Tim Parks, Salman Rushdie, Miguel Syjuco, and Ilija Trojanow.

In the “Conclusion” to her bookTranscultural Writers and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility, Dagnino gives a ten-point synthesis of the main elements of a transcultural orientation and its correlated transcultural narrative expressions. And they include:

1. Individuals (characters as well as writers and readers) thriving in, or at least positively challenging, the feeling of precariousness of one’s existence;

2. Movement experienced as freedom—an opening of new possibilities, beginnings, and becomings;

3. A feeling of being “in place”, not “out of place”—no longer guests, at home anywhere, despite the difficulties inherent in any process of adaptation and translation;

4. The perception of the boundaries between cultures and geographic entities as mobile, liquid, and changeable;

5. Identity conceived as a fluid process: no need for self-affirmation or categorical reference to ethnic roots;

6. Enriched through interaction with, and immersion in, multiple cultures;

7. The perception of the annulment, weakening, or supersession of traditionally conceived hegemonic centers;

8. The playful and creative engagement with the experience of foreign idioms, concepts, meanings, geographies, and verbally empowered characters, fluent in more than one language;

9. The blurring of the boundaries between self and other;

10. The sense of becoming experienced and understood as an empowering, although sometimes, distressful, dialogic process of mutual transformation and cultural confluence. (pp. 229-230)

These ten points sum up what Dagnino perceives as the ideal qualities of a transcultural writer, and they also offer a detailed prescription of how a transcultural novel should be written.

Comprehensive as this may seem, Dagnino’s prescriptive definition of transcultural novels remains a little less than satisfactory. Dagnino admits that an “element of indeterminacy” characterizes “the intrinsically metamorphic and to a large extent indistinct‘fuzzy’ nature of transcultural novels” (p. 212). While Dagnino repeatedly emphasizes the cosmopolitan attitude reflected in transcultural writing, it really fails to go into the specifics of the actual practice of how such writing can be done. Granting her principles, one would ask: what kind of transcultural competence does a transcultural writer need to write a story set in an alien culture? How should a transcultural writer write about another culture that is fundamentally different from his own? If, let’s say, an Australian transcultural writer wants to write a novel about an Australian’s experiences in China, what aspects of the Chinese culture and how much of it in depth must be broached in order to appear relevant to his thematic purpose? Apart from freely crossing borders, how should he treat the actual elements of Chinese culture in order to sound like a real “citizen of the world”? When an Australian writer writes about an Australian’s experiences in China, whether or not he calls himself a transcultural writer, these are all specific questions that must be addressed for theachievement of the kind of transculturalism that Dagnino wants to see in him. These are all real difficulties that the transcultural writer will find himself immediately confronted with when he sets about writing. And these difficulties arise not from the inability of the writer but from the complexity of “culture” itself.

2. What Is Culture?

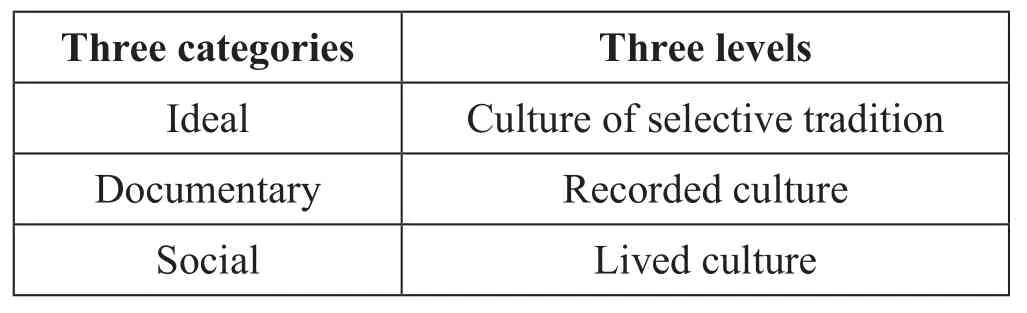

The key to transcultural literary studies is of course culture. But what exactly is culture?Cambridge English Dictionarystates that culture is “the way of life, especially the general customs and beliefs, of a particular group of people at a particular time” (“Culture”, online).Business Dictionarydefines it as “a pattern of responses discovered, developed, or invented during the group’s history of handling problems which arise from interactions among its members, and between them and their environment. These responses are considered the correct way to perceive, feel, think, and act, and are passed on to the new members through immersion and teaching. Culture determines what is acceptable or unacceptable, important or unimportant, right or wrong, workable or unworkable. It encompasses all learned and shared, explicit or tacit, assumptions, beliefs, knowledge, norms, and values, as well as attitudes, behavior, dress, and language” (“Culture”, online). In an article entitled “The Analysis of Culture”, Raymond Williams conceived of culture as “customary difference”: our culture is that which we are accustomed to and that which others are not. Custom, according to Williams, takes precedence over other modes of social validation, and its currency is difference. Thus, culture is “what differentiates a collectivity in the mode of self-validating direct inheritance—whose value, in return, is precisely that it binds the collectivity in difference” (Hartman, 2009). In the same essay, Williams argues that there’re three general categories in the definition of culture. The ‘ideal’ category refers to a state or process of human perfection, in terms of certain absolute or universal values; the ‘documentary’ category refers to the body of intellectual and imaginative work in which human thought and experience are variously recorded; the ‘social’ category refers to a particular way of life, which expresses certain meanings and values not only in art and learning but also in institutions and ordinary behavior. Williams divides culture into three levels that roughly correspond to the three categories: 1. the level of lived culture (of a particular time and place, only fully accessible to those who live then and there), 2. the level of recorded culture (of every kind from art to everyday facts), 3. the level of the culture of the selective tradition (a set of once valued works in a given period that continue to be valued in the new historical context of here and now).

?

For the purpose of general understanding, these, and especially Williams’ analyses, are all useful, but still very vague in a way, almost ungraspable if one wishes to use them to guide writers in their transcultural writing practice and literary critics in their transcultural literary analysis. Clearly, we need more concrete instructions on how transcultural literary writing and criticism could relate to the specific contents of cultures. A more recent essay that Per Aage Brandt published withLanguage and Semiotic Studiespromises to render more assistance. Entitled “WhatIsCulture?— A Grounding Question for Cognitive Semiotics”, the essay tries to answer Brandt’s own question by stating that culture is about the development of “practical behavioral habits and, in parallel, theoretical representations, including historical narratives, religious beliefs, myths and fictions, principles and ideals” (p. 40). And the forming of a culture is often “the consequence of the specific ways in which human individuals think and communicate, or rather: how wecombinethinking and communication”: “The study of cognition focuses on how we make sense of what happens, while the study of semiosis targets the ways in which we share the sense that things then make. Since most of what happens to us is related to our communication, the connection between cognition and semiosis has to be a two-way dynamic process. In the core of this process, we find what the philosophical traditions have come to call thesign” (pp. 40-41).

Believing that signs “are the elementary units of any science of culture” (p. 41), Brandt uses the Peircean triadic classification of iconic, symbolic and indexical signs for a critical examination of the processes of cultural formation:

Iconicity is pre-cultural and naturally intelligible…. Iconic expressions will then often become habitual; when third persons, observers, intervene and request participation in dual exchange, conventionalization will take place. Conventionalization is simply based on mimetic uptake of iconic, premimetic interaction. Iconic communication thus generates principles that can become codes and create symbolic communication outside of the initial context. Simple semiotic behaviors become habits that will eventually become norms. Emergence, maintenance, and sedimentation of such phenomena will produce cultural fixations. Icons becoming symbols are dynamic phenomena that constitute essential processes in ethno-genesis in general. (p. 44)

To Brandt, conventionalization, sedimentation and stabilization are the crucial procedures that happen if a pre-cultural iconic expression is to become a symbolic and indexical meaning. And these procedures constitute the chief mechanism of cultural evolution.

Iconic meaning (episodic, pre-narrative, playful) is created and communicated every second by human minds. A very small fraction of it is mimetically transmitted and stabilized as symbolic meaning, which further is monumentalized in landmarks, architecture, and ‘land-scaping’, that is, in the physico-indexical engineering of the habitat site. The result is an increasing cultural sedimentation, producing—in a sedentary community—a semiotic ‘geology’ made of a largenumber of layers of superimposed historical meanings-and-expressions (that tourists can visit:the Pyramids, Acropolis, Forum Romanum, The Great Wall…). (p. 45)

Brandt draws our attention to the difference and possible relations “between the semiotically ephemeral meaning productions of every moment’s iconic communication and the semiotically stabilized, symbolic meanings deposited by generalized communications within larger groups and indexically monumentalized into the physical ground of the habitat” (p. 46). And he goes on to state:

These sedimented and stabilized meanings are … essentially and universally of two distinct types: technical and normative. This is a rather important distinction, since the normative part of the symbolic sedimentation shapes and feeds into the ethnic (material and immaterial) culture of a community, whereas the technical part of the symbolic sedimentation forms the properly productive and distributive ‘system’, the ‘mode of production’, the default set of practical procedures that provides for the community, protects it, and thus assures its existence; I call the latter part the societal component. By contrast, no society survives on its normative culture alone, which can stay unchanged for very long historical periods, unaffected by changing life conditions of all kinds; whereas the societal practices have to be proactive and constantly adapt to changing natural conditions of the habitat. (p. 46)

Brandt’s cognitive semiotic definition of culture distinguishes itself from Williams’analysis by highlighting the process of sedimentation and stabilization. He argues that the “sedimented and stabilized meanings” can be divided into three different layers (and these differ from Williams’ three levels in that they come as a result of the process of sedimentation and stabilization):

1) infrastructures of material culture, including kinship formations, food-processing and toolconfiguring arts and crafts, habits of bodily and inter-subjective behavior, rituals, nutrition, medicine, and… language; 2) superstructures of immaterial culture, including ritually bound transcendent beliefs, myths and legends, music, songs, dances, sacred places, and… calendars; 3) functional societal structures of food-supplying work, territorial protection, institutions, rules and regulations determining the distribution of goods and property; routes and roads; institutions of education; productive and distributive technology and geographic navigation technology allowing contact and exchange with ‘foreigners’. (p. 47)

?

I’ve been going on so extensively about the definition of culture, because a sound framework will help us look deeper into the actual literary works and reap more meaningful insights about their authors’ (trans)cultural positionalities. Brandt’s theorization distinguishes itself from that of Raymond Williams by portraying culture as a dynamic process of becoming: iconic meanings become symbolic meanings in the process of time. This would be useful for the contemplation of the experience of cross-cultural contact. Brandt goes on to tell us that symbolic meanings can often be subdivided into three different layers, and that the functional societal structures shall be the most volatile and susceptible to change, as compared with the (im)material culture. Hopefully, this will help shed light on how writers write about another culture.

3. Critiques of Travel Literature

Much of what Dagnino claims for transcultural novels seems to me pitted against a more traditional form of writing that we call travel literature. Indeed, before it came to be called transcultural writing, literary writing that was set in a foreign culture or that treated experiences from a different culture was mostly travel writing. In the West, literary writing about cross-cultural travels has never been in short supply. From ancient classics likeOdysseyto Jonathan Swift’sGulliver’s Travelsall the way to more modern masterpieces including Joseph Conrad’sHeart of Darkness(1899), Ernest Hemingway’sThe Sun Also Rises(1926), and Jack Kerouac’sOn the Road(1957) andThe Dharma Bums(1958) and more contemporary works like Arundhati Roy’sThe God of Small Things(1997), Euro-American travel writings have to a certain extent always been at the centre of the Western literary canon. Because of this, travel writings have attracted a lot of serious scholarly attention.

But one notes not without some regret that travel writing has never been a genuinely favoured genre for literary critics. For instance, one of the best renowned early investigations in the area was of course Paul Fussell’sAbroad(1980), which afforded an exploration of British interwar travel writing as sheer escapism. Other interesting books that later came to be published includeGone Primitive: Modern Intellects, Savage Minds(1990) by Marianna Torgovnick, an inquiry into the primitivist presentation of foreign cultures,Haunted Journeys: Desire and Transgression in European Travel Writing(1991) by Dennis Porter, a close look at the psychological correlatives of travel,Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing(1991) by Sara Mills, an inquiry into the intersection of gender and colonialism during the 19th century,Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation(1992), Mary Louise Pratt’s influential study of Victorian travel writing’s dissemination of a colonial mind-set; andBelated Travelers(1994), an analysis of colonial anxiety by Ali Behdad. According to Graham Busby, Maximiliano E. Korstanje, and Charlie Mansfield, a great majority of the kind of travel literature we’ve seen serves to recreate “the portrait of the unknown”. As a mirror, this otherness legitimizes the selfhood: societies weave their own narratives in order to understand the events ofpolitical history as well as the place of the other.

Traditional travels and travelers were scrutinized from a slightly different angle in an essay entitled “The Semiotics of Tourism” by Jonathan Culler. Published in 1990, Culler draws readers’ attention to tourism as a new form of travelling and as a widely seen element of popular culture:

Tourism is a system of values uniting large segments of the world population from the richer countries. Groups with different national interests are brought together by a systematized knowledge of the world, a shared sense of what is significant, and a set of moral imperatives:they all know what one ‘ought to see’ in Paris, that you ‘really must’ visit Rome, that it ‘would be a crime’ never to see San Francisco and ride in a cable car. As MacCannell points out, the touristic code—an understanding of the world articulated by the moral injunctions which drive the tourist on—is the most powerful and widespread modern consensus…. (p. 4)

Why, then, do we dislike tourists? Why do some tourists denigrate other tourists? Why does tourism constitute an embarrassment, and become an easy target for those who would attack modern culture? Culler quotes Daniel Boorstin, and says that it is because the tourist, as opposed to the traditional traveler, is less adventurous and more foolish in their taste for the “elaborately contrived indirect experience, an artificial product to be consumed in the very places where the real thing is free as air” (p. 5): “The traveler, then, was working at something; the tourist was a pleasure seeker. The traveler was active; he went strenuously in search of people, of adventure, of experience. The tourist is passive; he expects interesting things to happen to him. He goes ‘sight-seeing’ (a word, by the way, which came in at about the same time, with its first use recorded in 1847). He expects everything to be done to him and for him. Thus foreign travel ceased to be an activity—an experience, an undertaking—and became instead a commodity” (Boorstin, 1967, p. 85).

Jonathan Culler sees earlier critics like Paul Fussell as constructing their arguments on the basis of just this argument. And he openly expresses his dislike of the logic obtaining behind this kind of binary opposition. He proposes that one could re-examine the whole thing from a semiotic perspective. For, a “semiotic perspective advances the study of tourism by preventing one from thinking of signs and sign relations as corruptions of what ought to be a direct experience of reality and thus of saving one from the simplistic fulminations against tourists and tourism that are symptoms of the touristic system rather than pertinent analyses” (p. 9). According to Culler, a culture is but a system of signs. If you want to know about it, it could only be through the mediation of deployed signs.

Critics of tourism, according to Culler, “make fun of the proliferation of reproductions associated with tourism: picture postcards, travel posters, miniature Eiffel Towers, piggy banks of the Statue of Liberty” (p. 5). To them these reproductions are mere “markers”: “Like the sign, the touristic attraction has a triadic structure: a marker represents a sight to the tourist” (MacCannell, 1976, p. 110). A marker in Culler’s eyes is any kind of information or representation that constitutes a sight as a sight: by giving information about it, representingit, making it recognizable (p. 5). The markers frame something as a sight for tourists:“The existence of reproductions is what makes something an original, authentic, the real thing—the original of which the souvenirs, postcards, statues, etc. are reproductions—and by surrounding ourselves with reproductions we represent to ourselves, as MacCannell astutely suggests, the possibility of authentic experiences in other times and in other places” (MacCannell, 1976, p. 148).

Culler contends that the denigrators of tourism should not feel “annoyed by the proliferation of tacky representations—postcards, ashtrays, ugly painted plates” because these representative markers have an essential semiotic function. “Not only do they create sights; when the tourist encounters the sight the markers remain surprisingly important: one may continually refer to the marker to discover what features of the sight are indeed significant; one may engage in the production of further markers by writing about the sight or photographing it; and one may explicitly compare the original with its reproductions (‘It’s not as big as it looked in the picture’; or ‘It’s even more impressive than I imagined’). In each case, the touristic experience involves the production of or participation in a sign relation between marker and sight” (p. 6). Culler concludes:

Tourism reveals difficulties of appreciating otherness except through signifying structures that mark and reduce it. It is tempting to see here nothing more than the result of an exploitative international order. But the Marxist condemnations of tourism as the reduction of otherness to caricature in complicity with multinational capitalism risks falling into a sentimental nostalgia for the organic or the unmediated that resembles nothing so much as the vituperative nostalgia of conservatives, who fondly imagine a time where the elite alone traveled and everything in the world showed itself truly to them. (p. 10)

Culler’s essay offers a semiotic defence of tourism as a contemporary form of global travelling. Through debunking the illusory fantasy in some tourists’ claim to authenticity, he, too, makes a critique of travelers as a whole.

In a slightly different way, the transcultural literary studies of the 21st century offer a sharp critique of traditional travel literature by pointing to the rigidity and self-centredness of its narrative perspectives. Perhaps without directly saying it, Dagnino took to task the traditional travellers’ inclination towards ethnocentric pride and prejudice. Her statements on transculturalism seem to have clearly inherited the logic of all these early critiques. She contends that, compared with transcultural writing which celebrates the freedom of moving beyond one culture, travel literature communicates a sense of exile and a general feeling of discomfort and restraint, homelessness, disorientation, displacement when people are placed in the context of a foreign culture. In a travel novel, therefore, boundaries between cultures keep us enclosed in the places of our birth, put a limit to our ability to think beyond our cultural conceptualizations, and impose on us an identity that weakens us and renders us inflexible, angry, and miserable wretches. For this reason, she thinks transcultural writing represents a clear sign of progress in the human grasp ofdifferent cultures.

4. Australian Novels About China

Any investigation into the dilemmas and difficulties of transcultural writing would be mere generalization if we don’t actually move into some actual examples. In this essay, I’ll stick with Dagnino by concentrating on Australian writers’ work and more specifically take a look at what Australian writers have done with China as a novelistic setting.

Australian writers started to introduce Chinese characters in their literary writings as early as the 1900s, but the first Australian novelist who took an active interest in writing about China didn’t appear until over four decades later. In 1948, Australian Melbournebased writer George Johnston published his first China novel,Death Takes Small Bites. The book was written under the influence of the general Western thriller tradition (Ouyang, p. 277) and was later followed byThe Big Chariot(1953),The Far Road(1962),Clean Straw for Nothing(1969), andA Cartload of Clay(1971).The Far Roadis sometimes considered the best of earlier Australia’s novels about China. Other Australian novels that were to follow in the next three decades included Russell Braddon’sWhen the Enemy Is Tired(1968), Margaret Jones’sThe Confucius Enigma(1979), Jeanne Larsen’sSilk Road: A Novel of Eighth-Century China(1989), Nicholas Jose’sAvenue of Eternal Peace(1989), and Alex Miller’sThe Ancestor Game(1992). In the 1990s, Nicholas Jose became one of the best known China experts and most respected literary writers about China. In the space of a little over ten years, he has published another three novels about China, which include:The Rose Crossing(1994),The Red Thread(2000), andOriginal Face(2005). Into the 21st century, Jose is joined by more Australian writers in the writing about China. One of the novelists is Linda Jaivin, who has most recently publishedA Most Immoral Woman(2010) andThe Empress Lover(2014).

In an essay entitled “Translating China”, Nicholas Jose places Australian literary writing about China in the context of the Western world as a whole. He argued that

the special status of the written word in Chinese society perhaps helps explain why China has attracted foreign writers for centuries. From the earliest travellers’ tales to reach Europe, to Voltaire and Coleridge, and on to the present day. China as strange, curious, awe-inspiring Cathay has drawn writers as a realm for tall tales, fantasy and the revelation of profound mysteries, a fabled zone of difference. (p. 36)

But he also stressed that China as a country “(bamboozles) the distinction between fact and fancy” and “persistently presents the problem of how to take what is written about it”(p. 36). Jose draws our attention to the fact that, while “[the] standard genre for writing about China is the eyewitness account, the report from the front that purports to tear aside the veil and reveal the real China”, such bald facts have often encouraged a kind of facadism, and “have squeezed out more imaginative kinds of literature” (p. 38). To helpbetter appreciate this, he makes a comparison between China and India:

[the] difference between India and China in the area of English-language fiction…is striking. India has been embodied in the most sophisticated forms of imaginative narrative, rooted in but not confined to realism:A Passage to India,The Raj Quartet,Midnight’s Children, Narayan, Naipaul, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The best known novels about China are Andre Malraux’sLa Condition Humaine(not an English novel), andThe Good Earthby Pearl Buck, a widely denigrated Nobel-Prize winner. Most of the novels in English with pretensions to art are little known, excessively artful and exotic, thinly autobiographical, or loose and sketchy. Among writers of the caliber of Joseph Conrad, George Bernard Shaw, Somerset Maugham, Harold Acton, Christopher Isherwood, Dorothy Hewett, Dymphna Cusack, and Alan Marshall, to name a few of those who visited China, none was inspired to produce major imaginative work from the experience—although Noel Coward wrotePrivate Livesin what is now the Peace Hotel in Shanghai. China has attracted writers, and turned people into writers, but has not helped to produce masterpieces. (p. 38)

Jose believes that China’s contrast with India should only be partly explained by the latter’s experience of colonization and its English language education. He thinks three other reasons will explain why China has not inspired as much imaginative treatment in western novelistic writing. One has to do with “the Chinese world-view”. The Chinese“create a chasm” between themselves and others. “The concepts of insider and outsider are fundamental at so many levels of life. The language, script and culture are expressions of this separateness, the manifestations of a society that is self-enclosed, hermetic and centred on itself” (pp. 38-39). The other has to do with the strange ways in which Chinese take the issue of human nature.

The traditional English-language novel depends on assumptions about human nature, about the individual in society, about cause and effect in the structure of a narrative. China challenges these assumptions, or prevents them from applying. The visiting novelist is largely denied access to Chinese human nature: he or she is restricted to external observative and imaginative projection, and both processes may say more about the writer than about the fictional characters. The Chinese may even challenge the assumption that there is one human nature. Maybe there is Chinese human nature and foreign human nature, as it is argued that there are Chinese human rights and foreign human rights. (p. 39)

The third reason for the apparent lack of interest in English-language novelists to write about China has something to do Chinese formal and aesthetic preferences. For “Chinese narrative is characteristically episodic, rambling, picaresque and fragmentary. Essay, memoir, reportage, fable are more characteristic modes of Chinese prose writing than the novel as we know it. In all these ways China resists prose narrative” (p. 39).

In contemporary Australian literature, Nicholas Jose is one of the most ferventadvocates of transcultural writing. This perhaps explains why he regrets the fact that so many Western English-language novels treat China as a place of exotica. He champions transculturalism and believes that Australian writing about China should move beyond mere “claims to real China” and arrive at a level of genuine unrestricted freedom in its approach to Chinese culture. At the “2014 Australian literary studies in China” conference held in Suzhou, China, he gave specific examples from a number of authors to explain his goal of transcultural writing. Incidentally, Jose was for quite some time a professor of English at the University of Adelaide where Dagnino worked. One has reason to believe that these two colleagues share a great deal in common about the benefits of transcultural writing.

5. An Analysis of Two Novels

For a member of one culture to behave “transculturally” towards members of another culture, he needs a cultural competence, which alone would enable people to interact effectively with people of different cultures and socio-economic backgrounds. In theory, cultural competence involves four basic components and they are: an awareness of one’s own cultural worldviews, a sound knowledge of different cultural practices and worldviews, an open attitude towards cultural differences, and good cross-cultural skills. In the context of literary writing, such competence in the individual, whether it be a writer, a narrator or a character, boils down to two things: knowledge and attitude. The amount of a different culture that is represented in a novel is often determined by how much the individual knows about it. What aspects of the alien culture will appear in the book and how they are handled depends on how the individual is attitudinally positioned. In this section, we can use Brandt’s cognitive-semiotic definition of culture to facilitate our examination and analysis of two Australian novels about China. One of them is Margaret Jones’The Confucius Enigma, and the other is Nicholas Jose’sAvenue of Eternal Peace.

5.1 The Confucius Enigma

Margaret Jones (1923-2006) was by training a journalist, and she worked as a foreign correspondent for Australian newspapers in Europe, North America and Asia. She opened a bureau for theSydney Morning Heraldin Beijing after the Whitlam Government established diplomatic relations with China in 1972. She did not speak Mandarin, but travelled extensively in the region. Jones was the firstHeraldjournalist based in China since World War II.The Confucius Enigmawas a novel inspired by her time in Beijing and the book was followed in 1985 by another novel set in Asia,The Smiling Buddha.

Subtitled “A Novel about Modern China’s Greatest Mystery”,The Confucius Enigmatells a story of intricate deception that unfolds amid the deepest secrets of modern China that centred around the 1971 disappearance of Marshal Lin Piao, the heir-apparent accused of attempting a Soviet-backed coup against Chairman Mao. The central protagonists are English journalist Alan Brock and Australian doctor Joanna Robinson, both stationed inBeijing. They are told Lin Piao is alive (Brock catches a glimpse of him) and that there’s a plan to rally pro-Soviet, anti-war forces around the resurrected Lin; but Brock’s help is needed in smuggling Lin out of the country (to Ulan Bator)—and the help of Australian doctor Joanna Robinson is needed in treating Lin’s severe case of Parkinson’s Disease. But very soon it becomes clear that Alan and Joanna have been duped: the whole Lin Piao scheme is a phony one, tricked up in order to embarrass the West and enhance the Chinese radicals. The novel ends with Alan being first taken prisoner and pressured (unsuccessfully) into confessing and then managing an escape.

The Confucius Enigmadoes a neat job with some complicated China politics, incorporating actual documents and news reports into the narrative. And its descriptions of Peking, Shanghai, and Mongolian locales are detailed with reportorial firmness. But the most interesting part of the book comes with the action that one frequently finds in the thriller novel because the basic elements of a thriller novel are all there: the cover-up of important information, innocent victims faced with deranged and villainous adversaries, the use of literary devices such as red herrings, plot twists, and cliffhangers, and a plot in which the baddies present obstacles that the protagonist must overcome. Ultimately, the goodies beat the baddies, and the villains are overpowered by the heroic protagonists.

As a cross-cultural novel,The Confucius Enigmawas clearly written under the influence of the Western thriller tradition of writing about the East. The innocent victims in this case are Brock and Joanna, and the villains are Mr. Wu and the rest of the Chinese. The Chinese, according to Brock and Joanna, start a conspiracy and they, in their unknowing innocence, are used and abused to such an extent that Brock nearly lost his life. The book follows Brock and Joanna’s experiences and consciousness through their encounter with the country. The plot of the story took Brock a couple of times away from Beijing city centre first to Russia, then to the rural villages near the Thirteen Tombs, then to Shanghai, and finally winds up with Joanna temporarily settling down in Hong Kong before going back to Australia. Brock and Joanna, along with other foreigners in China at the time, lived in a world of their own. Their only real relationship started with Mr. Wu, the language teacher, who drew them into a conspiracy that nearly took Brock’s life. If the experience gave Brock a chance to see a lot more Chinese people, Brock’s feeling about the country remained that of complete disenchantment. Throughout the novel, Brock and Joanna posed firmly against the culture that they faced.

If we use Raymond Williams’ theorization, Brock and Joanna’s exposure to Chinese culture is mostly in the “social” category. The level of culture that their time in China enables them to access is mostly different aspects of “the lived culture”. The novel makes no indication as to whether there was any effort on their part to reach beyond the immediate here and now for the “documentary” and “ideal” in Chinese culture. But clearly, Brock and Joanna were too busy attending to the immediate problems that they think are besetting them. In these circumstances, for Brock and Joanna, and perhaps for most other westerners stationed in China at the time, “the recorded culture” and “the culture of selective traditions” become either unavailable or simply uninteresting. Thewhole book’s references to the Chinese culture, therefore, remain on one single level, that is, the level of everyday life.

The Confucius Enigmatouches not a few bases in its presentation of Chinese social life. In the “iconic meanings”, which are, according to Brandt, largely “episodic, prenarrative, playful, pre-cultural and naturally intelligible” and “semiotically ephemeral meaning productions”, Margaret Jones describes the cityscape, climate, environment, and the people of China. Readers, therefore, find places like Zhongnanhai, Fragrant Hills, Chang An Street, Beidaiho, and Po Hai Gulf, but the capital city, according to Brock and Joanna, is uncomfortable with “the dust, the heat and the mosquitos” which either give you “Beijing Temper” or make you sick with “Beijing Throat”; Chinese people drink Maotai, and smoke Camel cigarettes, and most of the Chinese move around on bicycles and if they do drive a car, they don’t stop honking.

Within the “symbolic meanings”, the book’s emphasis is mostly on “the socialfunctional structures”, which, according to Brandt, should include “food-supplying work, territorial protection, institutions, rules and regulations determining the distribution of goods and property, routes and roads, institutions of education, productive and distributive technology, and geographic navigation technology allowing contact and exchange with‘foreigners’” (p. 47). Margaret Jones’s interest in this respect seems less in the important institutions that facilitate public well-being. Instead, her protagonists, Brock and Joanna, found only a country that was hectically dwelling on the threat of Russia on the outside, and inside itself, on a government structure that did everything to ensure continued unity in spite of the existence of different political factions. It was a country charged with authoritarian politics (p. 23). This communist state is headed by Chairman Mao and Jiang Qing, backed by the portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin. The PLA and Public Security are everywhere to see. The radio is forever broadcasting a small repository of songs like “The East Is Red”. And propaganda machines like New China News Agency,People’s Daily, andGuangming Dailyserve the system. However, from the top to the bottom, the system is torn between the radicals and the ultra-rightists. In the air is a deepseated worry about and perhaps fear of its unfriendly northern neighbor, the Soviet Union. Preparations for future warfare have never ceased while people continue to dig tunnels and manholes. Intellectuals who dare to criticize are labelled “ghosts and monsters”. People writedazibaoand chant slogans. Members of one faction “struggle” those of the other.

Brandt believes that a community’s material culture includes “kinship formations, food-processing and tool-configuring arts and crafts, habits of bodily and inter-subjective behavior, rituals, nutrition, medicine, and…language” (pp. 46-47).The Confucius Enigmagave very little time and space for most of these things enumerated on this list. For example, while the whole book revolves around a request made by Mr. Wu for some medicine to treat Parkinson’s Disease, almost nothing is said about Chinese medicine except a negative comment on it made by Joanna: “As far as I can tell, Chinese medicine is a load of old rubbish, but I could be wrong. Anyway, it doesn’t work for foreigners” (p. 39). The book, however, through Brock and Joanna’s eyes, does present quite a number ofChinese behavior habits. In speech, for instance, Brock and Joanna feel:

1. Chinese people are secretive:

1) Chinese are naturally secretive…But in nothing are they so secretive as about their own names. Even in families, they aren’t always used. It’s Little Sister, Third Brother, and so on. The Chairman is Lao Mao (Old Mao) to everyone except Chiang Ching, or so they say. So I’d stick to Mr. Wu or Wu laoshi… (p. 21)

2) …secrecy was a national obsession. (p. 49)

2. Chinese people dodge the truths:

1) Wu’s own lifestory was rather involved, and tended to change from week to week, Joanna sometimes wondered if she had come across a Chinese Walter Mitty… (p. 23)

2) Brock’s heart sank. He was going to get the good old Chinese double talk, the polite and elaborate obfuscation practiced by everybody from the cadres in the Information Department upwards. (But they are telling ties!) (pp. 175-176)

3) Brock would have been amazed at the document’s apparent reluctance to be specific. But he had grown accustomed to the curious Chinese abhorence of naming names when any other formula could be found…the avoidance of names in… (p. 176)

4) I’ve got pretty Chinese…kind of circumlocutory (p. 189)

5) Peking lives on rumors. (p. 193)

6) Brock was blunt himself, but he had long since learnt that, in China, straightforwardness is not a virtue.

7) Anyway…you’re always telling me Chinese habitually speak in proverbs and parables. (p. 111)

3. Chinese use lots of speech mannerisms:

1) Chinese like give “Brief Introductions” (p. 46)

2) Anyway…you’re always telling me Chinese habitually speak in proverbs and parables. (p. 111)

3) In China, minds become a memory bank for slogans easily tapped. (p. 234)

In bodily behavior, Brock and Joanna also discover some general patterns. For instance, they feel that Chinese “never sweat” (p. 51); Chinese have “the universal habit of spitting” (p. 152); Chinese people smoke obsessively (p. 174); Chinese people never “miss a chance of a nap” (p. 202); Chinese people live in “some luxury behind sleazy exteriors”(p. 240); Chinese people are “alert to enemies” (p. 207); And ordinary Chinese people engage in a lot of double dealing.

Of Chinese immaterial culture,The Confucius Enigmasays significantly less. The book’s only two references pertain to Bai Juyi’s poetry and Confucianism. Earlier in the book, Joanna was learning Chinese with her language teacher, Mr. Wu, who read a poem about the Tang Emperor Hsuan Tsong’s passion for her Lady Yang Kuei-fei (p. 17).

Joanna knew the story and she was constantly distracted while (not) listening. She thought ofher own visit to the Huaching hot springs: “That day at Huaching, the hot water—or was it the spirit of the Lady Yang, noted bedmate of emperors—had made her conscious of her present celibacy, and she moved her limbs in a remembered mimicry of pleasure…. How nice to share the bath with someone, limbs twining and untwining in the tingling water! Impractical, perhaps, to make love in the pool, but there was a good, broad wooden bench, and couple of coats for padding.” (p. 18)

If he is supposed to be teaching me Chinese, why the hell are we reading Tang poetry? We would be better off making shopping lists so I can go to the local markets instead of having to buy everything at the Friendship Store. She looked slyly at Wu from under her lids. I really believe with him, it’s a sort of wank. Anyway, why complain. Reading this sort of thing and licking our lips over it is probably the nearest I’m ever going to get to an affair with a Chinese man. …When they came to the place when Lady Yang was killed by the emperor’s soldiers:“Chauvinist pig!” Joanna said heatedly. Wu stopped reading, and looked anxious. “No, not you, Mr. Wu, The emperor and his bully boys.” …When they came to the place of the unfolding of the Emperor’s remorse, Joanna said: “Mr Wu, Mr Wu, Mr Wu, what do you think of me, I wonder. You’re the only man in my life at the moment, so I might as well speculate. Do you like me, or do I repel you, with my light eyes and my freaky hair, like a ginger Kanaka, as my mother used to say when she tried to get a comb through it. Do I frighten you, like I sometimes do the blackhaired toddlers in the park, who howl and clutch at their mothers’trousers when I try to talk to them? (p. 19)

Margaret Jones’ treatment of Confucius and Confucianism is equally tangential and strange. In a novel that centres on two westerners’ experiences in 1970s China, Confucius and Confucianism sound irrelevant. But the story of the novel takes place because Mr. Wu said they were doing something to help resurrect Marshall Lin Piao, after his sudden disappearance in the wake of a failed coup. Confucius comes in because Lin Piao was at the time criticized alongside Confucius, as the slogan of Pi Lin Pi Kong indicated. At the time, the whole question of how Lin Piao and Confucius could be related was a mystery to many, perhaps still mystifies people today. But Confucius came in anyway. At the beginning. As the mystery unravels, readers get told that Mr. Wu’s involvement in the whole conspiracy presumably to resurrect Lin Piao was a lie. Through his sister in Hong Kong, Joanna learnt that the whole thing had nothing to do with the disappearing Marshall. Instead, it was an attempt to get his grandfather, a Confucianist expert, to leave mainland China. Wu’s grandpa, at one stage, was told by the government to turn around against Confucianism although he had been studying Confucius for decades. Clearly not very pleased, the old man decided to leave the system. And through a trick, Wu managed to rally some support from the foreigners. To Brock and Joanna, the trick highlights the cunning and sinister character of Chinese people. And it is bound to let down anyone who is looking for Confucianist ideas here in the book. Brock and Joanna do believe that a mixture of animism, Buddhism, Taoism, Ancestor worship and Confucianism make upthe Chinese culture (p. 205), but the narrative of the text affords no explication for the specifics of Confucianism. And those ideas are obviously not what interested the novelist either.

Brandt contends that a small part of symbolic meaning “is further monumentalized in landmarks, architecture, and ‘land-scaping’, that is, in the physico-indexical engineering of the habitat site. The result is an increasing cultural sedimentation, producing—in a sedentary community—a semiotic ‘geology’ made of a large number of layers of superimposed historical meanings-and-expressions (that tourists can visit)” (p. 45). InThe Confucius Enigma, I find references to a number of such famous sites. One of them, for instance, is the Summer Palace, the other two are Western Hills and the Ming Tombs, which are “the only three out-of-town areas foreigners could drive to without a travel permit” (p. 128). The Summer Palace in warm weather is beautiful but “overcrowded and dusty” (p. 128) and among the lilies that carpet the “pale blue of the lake” is a Marble Boat that only reminds people of “the Dowager Empress’s ultimate folly” and the walkways around the lake only remind people of “the dragon lady” followed by “her retinue of eunuchs” (p. 33). The author goes on to tell readers that Western Hills is a place known to foreigners as a place for eating in its numerous restaurants and the Ming Tombs are perfect for picnics, “for foreigners with cars” (p. 128). Although she indicates that the two big tombs which have been excavated attract thousands of visitors who come to hear “cautionary tales of the Bitter past” from museum guides, Joanna preferred to lie in the grass at the tomb of the Emperor Hsuan Teh, her eyes half shut, watching the hawks wheeling in the pale sky, and beyond them, the sharp clear cut-out of the mountains, dark blue shading to purples in the folds (p. 129).

Joanna, who hated the dryness of flatness of Peking, had developed a passionate fondness for the Thirteen Tombs, and her spirits always rose as soon as the car turned off the main road and started up the Sacred Way, lined with its stone guardians. The valley itself was a miracle of soft growth, in a stony landscape of harsh browns and dull greens. (p. 129)

Obviously, Joanna’s interest in the Ming Tombs has little to do with the symbolic meanings behind it. In her eyes, the Ming Tombs, like Summer Palace, is beautiful as a place to go to. The sedimented and stabilized cultural meanings of the place have not become particularly relevant.

The overall impression that one gets while readingThe Confucius Enigmais that what Brandt perceives as different layers and meanings of a culture are treated under the pressure of forward movements of the narrative as one and the only layer. Symbolic meanings are sometimes deprived of their depth and they become very much like the precultural iconic meanings. When dealing with symbolic meanings, the novel has it so that material and immaterial cultures are deprived of their historical sedimentation and get treated like the socio-functional structures, as if they bear no particular significance. The whole story rushes forward as in other western mystery thrillers about the East, leavingno time for differentiation between the deep and the shallow. Apart from simply ridiculing the Chinese culture, the novelist shows no competence of discrimination.

The Confucius Enigmaportrays in Brock a British correspondent and in Joanna an Australian doctor. One has reason to speculate that, having been in China for a while, they would have learnt something about the different layers of its cultural meanings. Why then is it that the complexity of culture comes to readers in such a flattened singlelayer form? Some readers probably would explain it by pointing to the 1970s as a time in contemporary Chinese history when the communist party was determined to break away from the old oppressive culture that is represented by Confucius and Confucianism. For a novel to deal with a period of time when Chinese were determined to revolutionize its culture, it’s appropriate and probably more than natural to present a picture of the country as one flattened, or simply, maybe, without a culture. But that is only an excuse that does not always convince readers. To me, the key lies with the central protagonist, Brock. This British correspondent openly admits that, for professional reasons, he is in China not for culture; instead, he is here to sniff and smell trouble and he is proud of the fact that he has a good nose for it.

5.2 Avenue of Eternal Peace

The author ofAvenue of Eternal Peacewas born Robert Nicholas Jose (1952- ) in London, England, to Australian parents. He grew up mostly in Adelaide, South Australia. He was educated at the Australian National University and Oxford University, and he has traveled extensively, particularly in China, where he taught 1986-87, and served as Cultural Counsellor in the Australian Embassy Beijing 1987-1990. A full-time writer from 1991, he resumed his academic career as Chair of Creative Writing at Adelaide University in 2005. A past president of International PEN Sydney, he is general editor ofThe Macquarie PEN Anthology of Australian Literature(also published asThe Literature of Australia). He was Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University 2009-2010 and taught there again in 2011. He is Adjunct Professor with the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney, Professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University, and Professor of English and Creative Writing in the School of Humanities at the University of Adelaide.

LikeThe Confucius Enigma, Avenue of Eternal Peacealso revolves around a mystery. The central protagonist is another Australian doctor. Wally Frith is an Australian oncologist whose wife has recently died of cancer; grieving and feeling mocked by his own professional concerns, he arranges a stint at the Peking Union Medical College, with hopes of meeting Professor Hsu Chien Lung, who years before had done revolutionary cancer research. Although he also visits China because his missionary grandparents once lived and worked here, his chief purpose is to seek out this Chinese colleague. But Professor Hsu Chien Lung is difficult to find. During his stay in China, Wally travels from the gritty frozen north to the tranquil lakes and mountains of the south, looking for answers. Does traditional Chinese medicine contain a possible cancer cure? ProfessorHsu Chien Lung might have the clue, but did he ever exist? Is the elegant, enigmatic linguist, Jin Juan, really trying to help Wally in his quest? As he fights through a maze of bureaucracy and subterfuge, Wally falls in with people whose lives reflect the diversity of contemporary Peking: a model, shady traders, a basketballer, students, a dissident artist and a band of eccentric westerners. Finally, Peking opera turns to a passionate drama for freedom and democracy, when thousands of Chinese students occupy the streets of the capital.

In many ways,Avenue of Eternal Peaceis not terribly new in the methods adopted for writing about China. The novel uses an Australian visitor as its “central intelligence”and follows his experiences during his stay in China. At the centre of the novel is also a mystery. The story follows the protagonist all the way until his quest for truth comes to an end. The novel ends with the Australian leaving China after his one-year academic visit to the country. A number of the same things that we saw inThe Confucius Enigmaare also found here. For instance, dirty environment and dissidents, foreign correspondents and diplomats, slogans and street demonstrations, etc. But the book also differs fromThe Confucius Enigmain a number of ways. One of the differences lies in the fact that it does not use the simple plot pattern of a traditional thriller. The hero of the story is not a correspondent sniffing for trouble, nor is he involved in any conspiracy initiated by one faction for the purpose of opposing another. Instead, he is in China with lots of good will, given his intention to meet a Chinese colleague and learn from him professionally. The novel is lacking in the kind of precarious urgency that a thriller uses to push its characters forward. Without this narrative urgency, the novel could move forward with more time and grace for what lies beyond the immediately iconic.

Avenue of Eternal Peace, according to Raymond Williams, also focuses much of its attention on “the lived culture” of late 20th century China. This is perhaps as it should be, given the needs of the narrative movement. But the novel is by no means shallow because the author not only shows his abundant knowledge of China’s “recorded culture”, but also introduces the country’s “culture of selective traditions”. These together give the novel a cultural depth that is lacking inThe Confucius Enigma.

Avenue of Eternal Peacepresents no less thanThe Confucius Enigmain terms of China’s iconic meanings. The numerous places and construction sites, the grey sky disguised in haze and industrial chimney oozing of filthy smoke over the neighbourhood (p. 46), the different kinds of occupations, the horse-carts in the streets of Beijing, the bars and the tempting oriental women are some of the things that the visiting Australian doctor sees. ButAvenue of Eternal Peaceis obviously richer in its presentation of China’s symbolic meanings. Using Brandt’s model again, we find, for instance, that on the sociofunctional level, it gives a vivid description of the operational structures in which the average Chinese live their lives. For instance, through Wally Frith’s contacts with ordinary Chinese people, the book presents vivid pictures of the life of bureacrats, language teachers, athletes, doctors, academics, foreign traders, migrant workers, students, artists, naifs, taxi-drivers, bellboys, and waitresses; through Wally Frith’s host institution, thebook takes its western readers into a Chinese medical college and the Chinese hospital; Jin Juan works at a middle school, so readers get a chance to look into China’s secondary education system. Through Wally Frith’s visit to a restaurant, the author gives his Western readers some idea of how a Chinese wedding is carried out; through Wally Frith’s invited visits to some Chinese friends’ houses, the author takes his Western readers into the middle of Chinese family life; through Jin Juan’s date and relationship, the author presents a picture of how Chinese society regulates love and romance between young men and women; and through instances of intercultural friendship, the author portrays a new generation of Chinese people craving for leaving the country.

Avenue of Eternal Peaceshows an Australian novelist ready to dig under the surface of Chinese societal operations to know more about its culture. And Nicholas Jose’s interest in Chinese culture does not stop there with the most volatile and changeable part of it. About China’s material culture, he also dips quite deep. For instance, he writes about ChineseQigongand Chinese Taoist temple fairs and he writes about the “Dragon Well” tea. And he writes about Chinese cuisine and Chinese weddings. One evening, Wally Frith came to a restaurant to eat. He was immediately overwhelmed by a wedding banquet:

All about lay the trophies of jubilant and unabashed feasters: duck heads, fish spines, orange shrimp shells and waxy chunks of winter melon. Bottles and glasses clinked. Plates tipped rich fatty juices to the floor. Wally drank beer and his face flushed. Those around him passed little cups of fiery spirits and threw sweets. At the place of honour a bride in traditional jacket of red satin glowed like red wax beside her proud spotty bridegroom. Friends and relations stuffed themselves. (p. 4)

Avenue of Eternal Peacealso presents some of the author’s observations about Chinese speech and behavior habits. Through Wally Frith, one is told (as inThe Confucius Enigma) that Chinese taxi-drivers can talk (p. 33); Chinese people are secretive (pp. 170-171); Chinese people bear strange names such as “philosopher horse” and “building the country” (p. 153); Chinese people make and eat dumplings (pp. 58-59).

Avenue of Eternal Peacehas a central position for Chinese medicine and Chinese language. The novelist has it so that Wally Frith comes to China because he wants to see this alleged expert in Chinese medicine, Hsu Chien Lung, who, to him, probably knows the secret to cancer therapy. If Chinese medicine is sheer rubbish for the foreigners inThe Confucius Enigma, it is the ONLY reason that impelled Wally Frith to come to China. Jose is equally into the Chinese language. Wally’s impression is that Chinese often speak in idioms and use a lot of old sayings (p. 13). And the author’s explication, through Jin Juan, of the Chinese idiom,Ye Gong Hao Long, epitomizes his knowledge and interest:

‘The old man is fond of dragons,’ she said. ‘It’s one of our sayings. This old guy was a dragon fanatic. He studied them, painted them, filled his house with toy dragons. One day a real dragon popped its head in the window. The old guy died of fright. It means you like the idea ofa thing, but you can’t cope with the reality.’ (p. 62)

Jose’s knowledge of and readiness to write about the Chinese immaterial culture is equally remarkable. In each of the early chapters of the book, he treats a part of it. When the first chapter opens, for instance, we find Wally arriving in Beijing only to experience at first hand the lunar Chinese New Year (Spring Festival) celebration. In the third chapter, Wally is taken by a Chinese friend Eagle for a visit to a Taoist temple. In the fifth chapter, Wally comes back from Beidaiho only to find people observing their Clear and Bright Festival (All Souls Day) and commemorating their deceased. In the seventh chapter, Wally goes out with Eagle’s family to watch Peking Opera.Avenue of Eternal Peacetestifies to the novelist’s knowledge of all of these and much more.

Avenue of Eternal Peaceis not lacking in the representation of cultural monuments which stand as China’s physico-indexical meanings. The Forbidden City, as a constant landmark of the capital city, appears 6 times in the book. Young lovers date behind it and visitors from all around the world come to see it. The Great Wall is another landmark. Other such places in Beijing that Wally Frith knew and visited include the Old Summer Palace and Tiananmen Square. When Wally Frith came to Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, he and Jin Juan visited Lu Hsun Museum. “The museum showed touching photographs of the early advocates of democracy, a century ago, and later the martyred writers ofLa Jeunessewho had felt a new ardour heat their country” (p. 225).

Culture, according to Brandt, is all about sedimentation and stabilization.Avenue of Eternal Peacepresents enough of Chinese culture at all its layers to show that the novelist really cares about the place that provides his story with its setting. In this sense, it is completely different from all earlier Western thriller novels about the east. Nicholas Jose’s knowledge of Chinese language and the culture behind it and his experience as cultural counseller at the Australian Embassy in China not only make him a different writer but also make his writing about the country’s culture possible. His novel is not flat in its cultural representation; instead, it has a depth and shows a complexity in the culture that is being depicted. This kind of treatment of Chinese culture at a time when more and more westerners were beginning to turn to the east and learn about the country is all too appropriate, but it also reflects the novelist’s determination to be different from earlier western writers.

While presenting the different layers of Chinese culture, Nicholas Jose shows admirable knowledge. OccasionallyAvenue of Eternal Peacewould make a mistake or two and betray problems in the novelist’s understanding when it has Wally Frith reflect on some aspects of Chinese culture. For instance, the Great Wall, according to the novelist,“came down to the ocean’s edge in an attempt to stop (the invadersfrom Japan and Korea)” (p. 57). Speaking of the ancient tragedySnow in Summer, the novelist explains it in terms of a young woman falsely accused of trying to murder hermother-in-law. Most Chinese readers would not feel bothered by these errors.

But throughout the novel, one notices that, on each layer, the author communicatesan intriguingly non-committed and even disparaging attitude towards the culture he is committing so much effort to writing. For instance, the book begins with a highly critical description of Mrs. Gu who helped with the reception when he arrived. She is, according to Wally Frith, chameleon-like, changing her attitude as soon as she took him to his place of accommodation. She speaks, of course, horrible English. During the rest of his stay, Wally Frith feels Chinese are a mysterious people, because they have many secrets (p. 13) and they always have something to hide (p. 116). China, according to Wally Frith, is a disorganized place where so much seemed to be a formless, fluid mess (p. 84). Chinese bureaucracy is badly corrupted (p. 182) and Chinese business is dishonest. The Foreign Trader buys and sells Han bronzes, Sung porcelain, girls, boys, dope, heroin and excellent exchange rates (p. 133). The author arranges for one of Wally Frith’s Chinese friends (Eagle) to recount this story about Chinese dumplings:

‘Haven’t you heard?’ Eagle stood in the doorway. ‘In the west of the city the dumplings have human meat in them. They arrested some people last weekend. A man and a woman and the woman’s little brother. They’d been luring hawkers from the country up to their flat and killing them and turning them into dumplings. I know someone who lives over there. She said they couldn’t catch any more peasants so they were going to eat the brother. He ran for the police. The neighbours found a thighbone in the alley. They thought it belonged to a pig. The local doctor knew better.’ (p. 43)

The whole Chinese nation relies onguanxifor everything (pp. 267-269). The Chinese academia is also rotten (p. 51), because the medical college he is visiting is headed by a plagiarist whose experience shows how intellectual dishonesty thrives (p. 181). The Chinese language, according toAvenue of Eternal Peace, cannot express the things that the human body can do (p. 177). China is still a closed system like a fine net that ensnares (p. 209), and an unfree country where dissidents are put under strict surveillance monitoring (p. 178).

Wally Frith has this to say about the Chinese Spring Festival firecrackers:

He was woken by the sounds of military attack… The sky was flickering, the ground bubbling with light. In squeals, whistles and rat-a-tat, the New Year had come. Baskets of fireworks hoarded for this midnight were erupting across the city, not to end the world but in a wild celebration of renewal, as everyone exploded their banger, flew their golden phoenix, unfurled their rainbow dragon. The red sky smelled of burning chemicals and paper from repeated onslaughts of flame and sparkle, flak and glittering rain. All across China, for thousands of miles, as for centuries, the people marked a new beginning by waging war on their besetting demons, firing heaven with the flame powder they had invented. (pp. 10-11)

Through Wally Frith, we hear this comment on the Forbidden City:Could this nocturnal wasteland really be the northern capital, navel of the universe, seat of Heaven’s Mandate? Was it from here that astronomers threw nets across sky, imperial gardeners produced blood-red peonies with golden stamens hieratic opera singers electrified the air, women grew contorted for beauty, and men cut off their balls for power? Reverberated the gong to the limits of the four seas? Imperial puppets turned to day… Born again as ‘Beijing’in the official Romanization of new China’s standard language, a tongue no one spoke, the city of ghosts had been repossessed by peasants, soldiers and officials rising to the surface of the great Chinese ocean. City of devastation, ring roads, high-rise and infernal dust, trial and error, whims put into praxis, it was a masterwork in the stripping of human dignity. Yet here at its heart was the other masterwork of Time waiting monumentally in shadow. Time’s two masterworks, stripping down and building up. (pp. 6-7)

Wally Frith is not terribly impressed by Chinese Taoism:

(Eagle took Wally to see a Taoist Temple.) Full of energy, he led the Doctor across the swept flagstones to the first courtyard where monks with topknots were pottering about. He tolerated the foreigner’s interest in such quaint things, though he had seen too much fakery to regard these Daoists as close to any source. Yesterday’s stinking superstition was today’s colourful tradition under the Party’s magic wand; and the monks, with baggy robes and interned eyes, performed well.

…

Wally was thinking philosophically of Lao Tzu. Yet Eagle was the truer Daoist, always taking the path of least resistance. …

“Do you believe in religion?”

…

“I don’t believe,” Eagle stated flatly. (pp. 33-35)

When Wally Frith moves through “the cavernous chambers” of Lu Hsun Museum, he feels pissed off by its “orthodox Marxist-Maoist storyline”:

Wally was struck again by the despair in China’s history, an evolution so slow and chancy as scarcely to deserve the name of progress, mutation rather, each wave of reform, enlightened, idealistic, suicidal, feeding straight back into the self-devouring maw of the organism. The museum showed touching photographs of the early advocates of democracy, a century ago, and later the martyred writers ofLa Jeunessewho had felt a new ardour heat their country; and in the last equivocating chambers the attempt made to establish an affinity that never existed between Lu Hsun and Mao Tse Tung’s policy of art in harness to the revolution of the proletariat. It was a museum of sorry lies that made any real hope go soggy, Wally thought. (p. 147)

In a word, a critical negativity permeates all Wally Frith’s engagements with Chineseculture. After reading the novel, one feels that even the title carries an obviously ironic undertone in relation to the Chinese craving for peace. The novelist predicts that, as the centerpiece of the capital, Avenue of Eternal Peace may lie as an embodiment of the Chinese wish for stability, but the system perhaps ensures that peace here in the country would not last long. To confirm this prediction, Jose, in the original “Postscript”, gave a detailed account of what happened on Tiananmen Square after the novel was completed.

Where does this sense of superiority and even antagonism against Chinese culture come from? In “Translating China”, Nicholas Jose states familiarly thatAvenue of Eternal Peacehad its inspiration from a kind of “principled artistic witness” in Chinese culture which has “attracted Australian writers”. Having heard so many Chinese stories about artists and intellectuals, he felt attracted to “the wild lifestyle and passionate conviction of some contemporary Chinese poets and he wanted to write a book in which ‘poets’dreams are set against the state’s claims” (p. 41). He said he “had been in Peking looking at post-modern artworks with people who at the time lived in unplumbed, pre-modern rooms, artists outlawed by a system that is at once high-tech sophisticated totalitarian and medievally feudal in what it demands of and does to people” (p. 42). And in Wuhan, he had “talked to a relation of the bodyguard who had accompanied Mao on his epic swim. The bodyguard was a peasant who had become a Communist Party member and security officer. He died in 1991, having lost all faith and hope in the system he had served with utmost loyalty all his life” (p. 42). From these anecdotal accounts, it is not difficult to find out whyAvenue of Eternal Peaceis filled with a paradox. On one hand, you see a real expert on Chinese culture; on the other hand, you get a genuine voice of opposition.

6. Conclusion

In this essay, I’ve intended to take a look at the recent literary critical concept of “transcultural writing” as it is defined by Dagnino, and I’ve used two 20th century Australian novels set in China to help examine how western writers have written about Chinese culture. My central question is: how should a transcultural writer write about another culture or treat other cultures for his novel to become a truly transcultural novel?

The Confucius EnigmaandAvenue of Eternal Peacegive us two examples of the way in which Australian writers have written about Chinese culture in the 20th century. And Brandt’s concept of sedimentation and stabilization of symbolic meanings in his cognitive-semiotic definition of culture helps us see how Margaret Jones and Nicholas Jose differ in their treatment of another culture. InThe Confucius Enigma, Margaret Jones seems more interested in creating an exciting story plot than presenting Chinese culture. For this reason, the novel’s engagement with Chinese culture is minimally restricted to the iconic meanings (Lin Yutang calls these the “mass of foreground details” by which foreign observers are often swamped, p. 13) and the socio-functional structures within the symbolic meanings. And China, therefore, is treated in this book as a mere setting for a mystery thriller.Avenue of Eternal Peace, by comparison, has an equally interestingstoryline with its protagonist going to great lengths in order to seek out the person he comes to China in quest of. But it’s much more relaxed in its story action. Nothing of the kind of conspiracy and danger inThe Confucius Enigmabesets Wally Frith, so he has more time for observing Chinese culture beneath the surface of iconic meanings. Through Frith, Nicholas Jose not only looks into the socio-functional structures of the Chinese society but also examines multiple elements of the country’s material and immaterial culture.

From a purely cultural perspective,Avenue of Eternal Peaceis undoubtedly more fleshed out thanThe Confucius Enigmain its representations of the 20th century Chinese life. In this sense, it testifies to the enviable amount of knowledge that Jose as a contemporary China expert of Australia has managed to accumulate. However, from Dagnino’s transculturalist point of view, the two novels would perhaps seem more similar than different. For one thing, both novels portray visiting foreigners coming to China and staying here briefly for professional purposes. New to the country, they face a common job of surviving the environment and whether or not they would reach out to get to know about this culture depends on how well they settle down in their temporary expatriation. The difference between Brock & Joanna and Wally Frith in their engagement with Chinese culture, therefore, is a matter of degree. Both of them cross national borders and pose as transpatriates capable of “transcending” cultural differences. And both novels are permeated by a negative attitude and a feeling of superiority and contempt held by bigoted western observers. For Wally Frith, China is a disorganized place, to say the least, and a country in desperate need of western intervention. In Brock and Joanna’s case, it is a worse feeling of hostility which escalates to physical confrontations. For all these protagonists, Chinese culture is unacceptably strange and mysterious and deserves to be left behind as soon as possible. These similarities encourage us to believe that, if there is a serious disparity between traditional and transcultural writing, it would be much safer to say that both of these novels still belonged in the traditional category of traveller’s tales.1

The two novels start us thinking about Dagnino’s theorization of transcultural writing because her emphasis on “transcending” only implies an aloofness and detachment. Dagnino’s emphasis means: transcultural writers must not write like the early travel writers for the sake of mere exotica or to pick fault with other cultures; instead, they should take different cultures with understanding. But Dagnino’s notion of “transcending”begs many questions. On one hand, “transcending” could imply loftiness that comes from an aloofness and detachment based on knowledge. “Transcending” cultural differences often does not mean giving up one’s prejudices and bias in favor of direct engagement, or a readiness to share all the different layers of another culture’s symbolic meanings, not just knowing it, understanding it but partaking of its daily operations and learning to feel the same way about all different elements of another culture. But genuine transcultural writers should have, in addition to the right knowledge of and right attitude towards other cultures, a genuine sense of commitment and belonging in other cultures and they can actually engage and share and positively participate in the daily operations of anotherculture.