REFLECTIONS IN THE REARVIEW

BY MATT TURNER

REFLECTIONS IN THE REARVIEW

BY MATT TURNER

A man stretches in bed, smoking a cigarette in front of a television,looking off into the distance. The closer you get, the more realistic he looks. But when you step back, the oil painting’s large gold frame, tilted onto one corner, becomes the prominent feature. It feels a bit like a window.Zhao Bandi’s “Young Zhang” (1992) looks back at us—as if we’re the ones on the inside of the frame,being stared at by Zhang.

Five years in the making, Art in China After 1989:Theater of the World, a voluminous exhibition of Chinese art that will run until January 7 at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum, stares right back at us. According to chief curator Alexandra Munroe, it is a “workshop-like exhibition” that emphasizes the “significance and urgency” of concept and ideabased artworks from China. It’s exhilarating.Not many exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art of this scale have been attempted. As Munroe stated in her opening comments, it is the largest ever, and asserts “a set of propositions” about a body of work that stretches from the end of the 1980s until 2008. Many prod those unfamiliar with the diversity and intensity of the work into unfamiliar territory and considerations—like Zhao’s painting does.

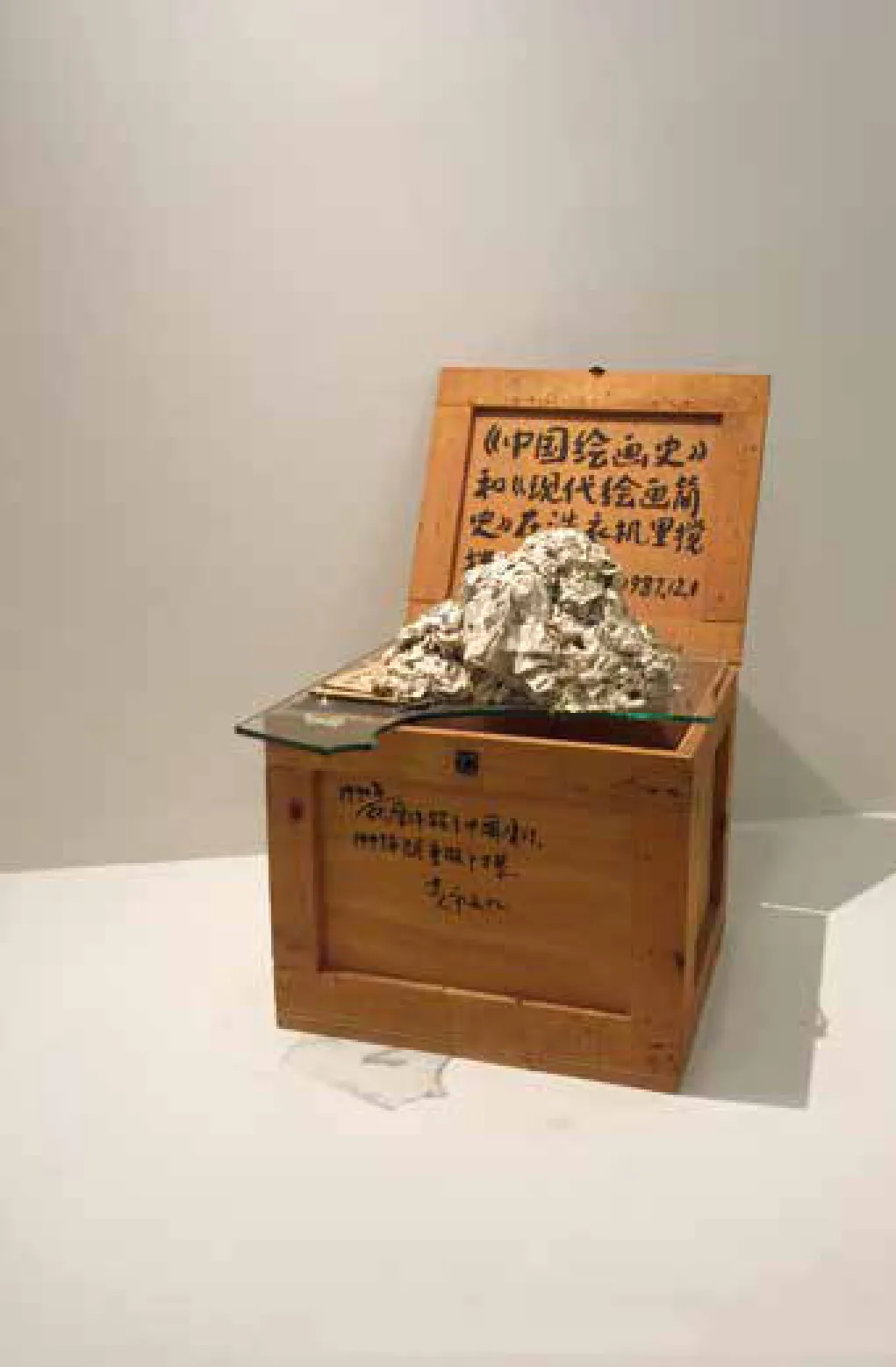

Huang Yongping’s “Two-Minute Wash Cycle” (1987)

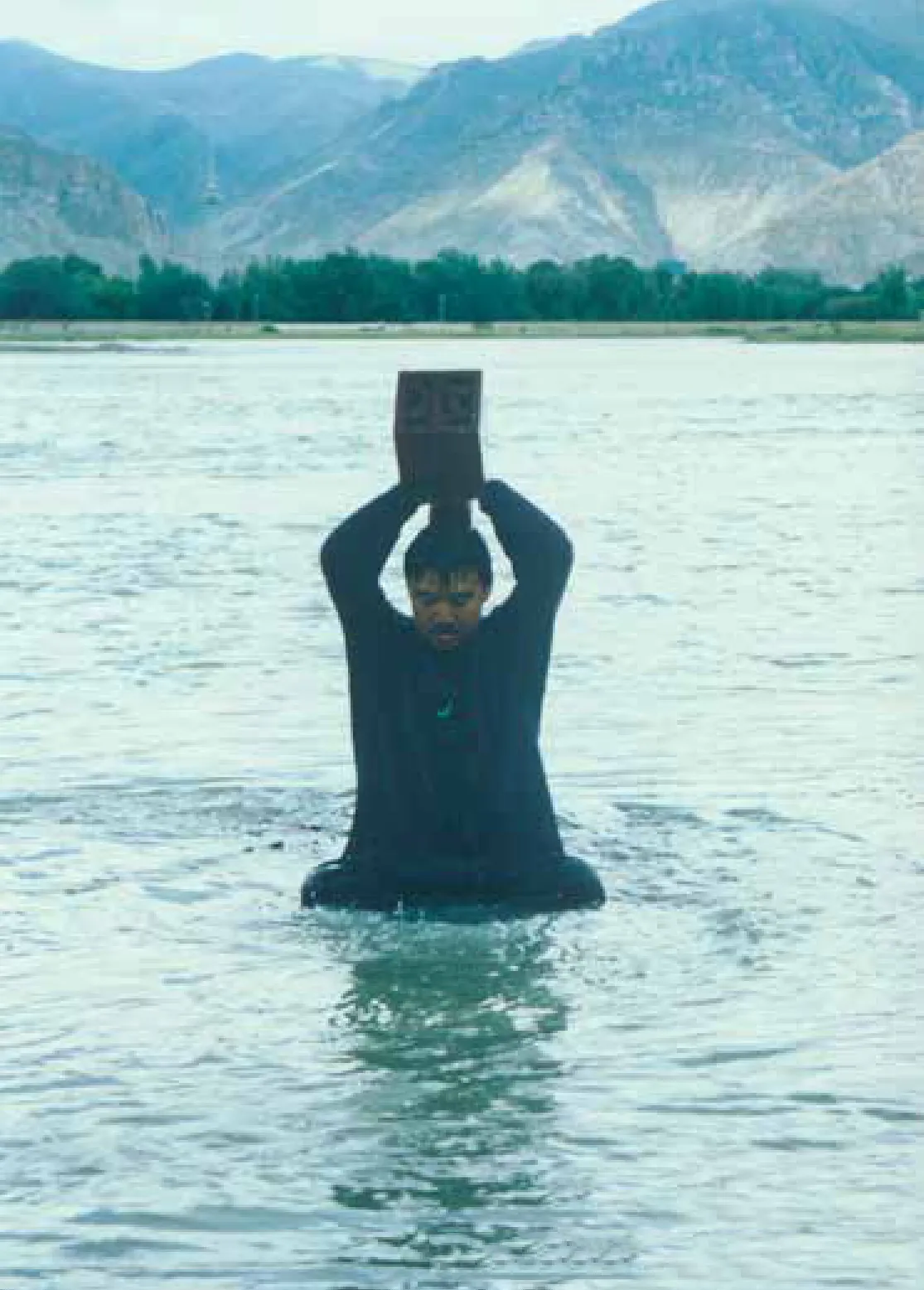

Song Dang’s “Stamping on Water” (1996)

But the main tendency is experimentation. One foundational photography work in the exhibition, Song Dong’s “Stamping on Water” (1996), was a performance: Song used an outsized chop (a stamp used to authenticate Chinese documents) to “stamp” the fl owing waters of the Lhasa River. We might ask ourselves what, in the end, was marked—water, or time? And the chop—which reads 水,water—is a certification, but for whom, or what purpose?

According to co-curator Philip Tinari, a work like Song’s“is more cerebral than strictly retinal, but also in relation to research that has been ongoing since the 1990s on ‘global conceptualism.’” That “research” is more interested in the mind than the eye, and despite being pioneered by artists like Marcel Duchamp a century ago, remains a novel and controversial approach, one that often privileges concept over technique.

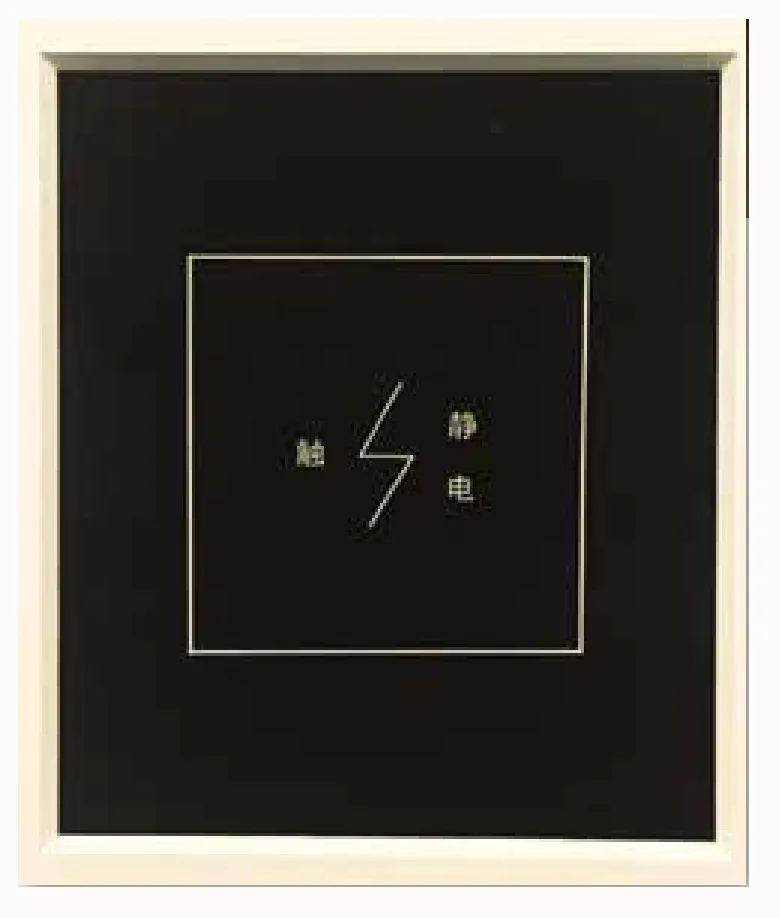

The exhibition draws on avant-garde Western predecessors as well as indigenous traditions, evidenced in an early work, Huang Yongping’s 1987 “Two-Minute Wash Cycle.” It’s a mess of paper scraps, the remains of histories of Chinese and Western art blended together in a washing machine, the “research” also seen in the diagrams and text-based works of the Beijing-centric Tactile Sensation Group. All of these artists use (often Western-pioneered)avant-garde strategies as starting points for questioning the efficacy of their Chinese contexts.

The timeline of the exhibition marks its own context.In 1989, “Magiciens de la Terre,” a large-scale exhibition of contemporary Chinese art, debuted at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, the same year the “China Avant-Garde”exhibition opened at Beijing’s National Gallery. These events are symbolic for simultaneously looking outwards while advocating for local context. Art in China After 1989:Theater of the World claims these moments as the beginning of a serious engagement with global contemporary art that saw its completion with the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

In this narrative, the Olympics was when China indisputably appeared on the world stage, and when the fierce experimentation that characterized its contemporary art was fully recognized by the larger world as more than a Chinese phenomenon. This was achieved through symbolic architectural masterpieces—like the Olympic “Bird’s Nest” Stadium—and also by forcing non-Chinese artists to confront aesthetic concerns that may not have been within their purview. To a degree, China had integrated with the rest of the world.

According to Tinari, Chinese artists during the exhibition’s period developed “an increasingly fluid sense of where they fit in relation to a global artistic conversation.” This undoubtedly led to their works being recognized by foreign cognoscenti—such as by putting on an exhibition at the Guggenheim. But it has not necessarily been a smooth road.

Shortly before its opening, media reports about pieces to be included by Xu Bing, Huang Yongping, and couple Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, sparked an outcry over animal cruelty (there was particular ire for the latter’s 2004“Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other,” a seven-minute video showing pit bulls on treadmills struggling to fight each other). They were deemed to violate standards of animal rights and decency, and inspired petitions and well-organized demonstrations. Ultimately, the museum withdrew the exhibits, citing threats against Guggenheim staff, but the climb-down provoked its own controversy: “Pressuring museums to pull down artwork shows a narrow understanding about not only animal rights but also human rights,” artist Ai Weiwei told The New York Times.

A 20-meter dragon made of bicycle tubes greets visitors as they arrive

Yet touring through such an expansive exhibition, the absence of these pieces makes a powerful statement about artistic direction and mutual in fl uence, especially regarding international practices, influences, and standards. Although the works were withdrawn, the petitioners and Chinese artists nevertheless were pushed into a dialogue, or at least a confrontation, of equals. Each promoted their own vision of what constitutes art, and even ethical behavior.

This raises larger, recurrent questions about the exhibition as a whole. The artists all seem to question where they came from, who they are, and where they are going—exactly as Paul Gaugin asked in his 1897 work “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?”painted after he had left the unidirectional Parisian art world and relocated to Tahiti. Today New York wants,even needs to hear artists’ answers more than ever. More importantly, however, we are reminded of the fundamental questions they are asking.