Genetic improvement of heat tolerance in wheat:Recent progress in understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms

*

State Key Laboratory for Agrobiotechnology,Key Laboratory of Crop Heterosis and Utilization,Beijing Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Improvement,China Agricultural University,Beijing 100193,China

1.Introduction

Wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)is one of the world's staple crops,and high and stable yield is the most important target for wheat breeding.As a cool season crop,wheat has as an optimal daytime growing temperature during reproductive development of 15°C and for every degree Celsius above this optimum a reduction in yield of 3%–4%has been observed[1].However,the average global temperature is reported to be increasing at a rate of 0.18°C every decade[2].Thus,the likely impact of heat stress in wheat has recently attracted increasing attention[3–8].In this review,we summarize current knowledge about the impact of heat stress on wheat,including the underlying molecular mechanisms and genetic improvement of heat tolerance,especially the results of recent research in China.

2.Heat stress damage to cellular structure and physiology

Heat stress causes damage to cellular structure and affects various metabolic pathways,especially those relating to membrane thermostability,photosynthesis and starch synthesis[9–17].Denaturation of proteins and increased levels of unsaturated fatty acids caused by heat stress disrupt water,ion,and organic solute movement across membranes,leading to increased cell membrane permeability,and in turn,inhibition of cellular function[11].High temperature adversely affects photosynthesis in a number of ways[12].Thylakoid membranes and PS II are considered the most heat-labile cell components[13].Thylakoid membranes under high temperature show swelling,increased leakiness,physical separation of the chlorophyll light harvesting complex II from the PS II core complex,and disruption of PS II-mediated electron transfer[14].Thylakoids harbor chlorophyll and damage to thylakoids caused by heat can lead to chlorophyll loss[13,14].Starch synthesis is highly sensitive to high temperature stress due to the susceptibility of the soluble starch synthase in developing wheat kernels[15,16].Starch accumulation in wheat grains can be reduced by over 30%at temperatures between 30 °C and 40 °C[17].Thus,the ability to synthesize,store and remobilize starch at high temperature is crucial to determination of grain sink strength.

3.The effects of heat stress on agronomic traits in wheat

Temperature can modify developmental and growth rates in plants.Correspondingly,heat stress affects agronomic traits at every developmental stage,but the pre-flowering and anthesis stages are relatively more sensitive to high temperature compared to post-flowering stages[11,18,19].Specifically,short periods of high temperature at the pre-flowering and flowering stages can reduce grain number per spike and yield.This can be attributed to lower ability of pollen to germinate,and to the rate of pollen tube growth[19].For example,wheat plants exposed to 30°C during a 3-day period around anthesis had abnormal anthers,both structurally and functionally,in 80%of florets[11].Yield losses during post-flowering stages were due to the abortion of grains and decreased grain weight.Moreover,the early grain filling period is relatively more sensitive than later periods to high temperature stress.Variation in average growing-season temperatures of±2 °C can cause reductions in grain production of up to 50%in the main wheat growing regions of Australia.Surprisingly,most of this can be due to increased leaf senescence as a result of temperatures >34 °C[20].In addition,heat stress during the grain filling stages also strongly affects grain quality[21,22].

The wheat-growing regions of China are divided into three major agro-ecological production zones:the northern China winter wheat region,southern China winter wheat region,and spring wheat region[23].Accordingly,heat stress that affects wheat growth in China can be divided into two categories of cause:dry-hot wind,and high temperature with high humidity.Dry-hot wind,defined as strong wind with high temperature and low humidity,often occurs in the higher latitude areas of northern China.High temperature with high humidity often occurs in the southern production region,especially the Middle-Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Plain[24].This landmark study of the impact of temperature on yield in winter wheat in China showed that post-heading heat stress was more severe in the generally cooler northern wheat-growing regions than in the generally warmer southern regions,but the frequency was higher in the south than in the north.It was estimated that post-heading heat stress and average temperature explained about 29%of the observed spatial and temporal yield variability[24].Recently,simulations based on future environmental predictions indicated that by year 2100 projected increases in heat stress would lead to mean yield reductions of 7.1%and 17.5%for winter wheat and spring wheat,respectively[25].However,with projected increases in world population the demand for wheat grain would increase to 776 Mt by 2030,a 26%increase on 2016 productions(616 Mt)[26].Therefore,China's effort to maintain basic self-sufficiency in the future will face the challenge posed by global warming and the resulting increase in the occurrence of heat stress[27].

4.QTL mapping and the major loci influencing heat tolerance in wheat

Heat tolerance is quantitative in nature,controlled by a number of genes/QTL(quantitative trait loci)[28,29].Over the past three decades efforts have been made to elucidate the genetic basis of heat tolerance.Langdon chromosome substitution lines were firstly used in mapping heat tolerance genes and associated genes were found on chromosomes 3A,3B,4A,4B,and 6A in 1991[30].Xu et al.[31]later reported that chromosomes3A,3Band 3D were associated with heat tolerance in wheat cultivar(cv)Hope.Using chromosome substitution lines between Chinese Spring and Hope,chromosomes 2A,3A,2B,3B,and 4B of Hope significantly enhanced heat tolerance[32].Collectively,chromosomes 3A and 3B appeared to harbor key genes controlling heat tolerance in wheat.

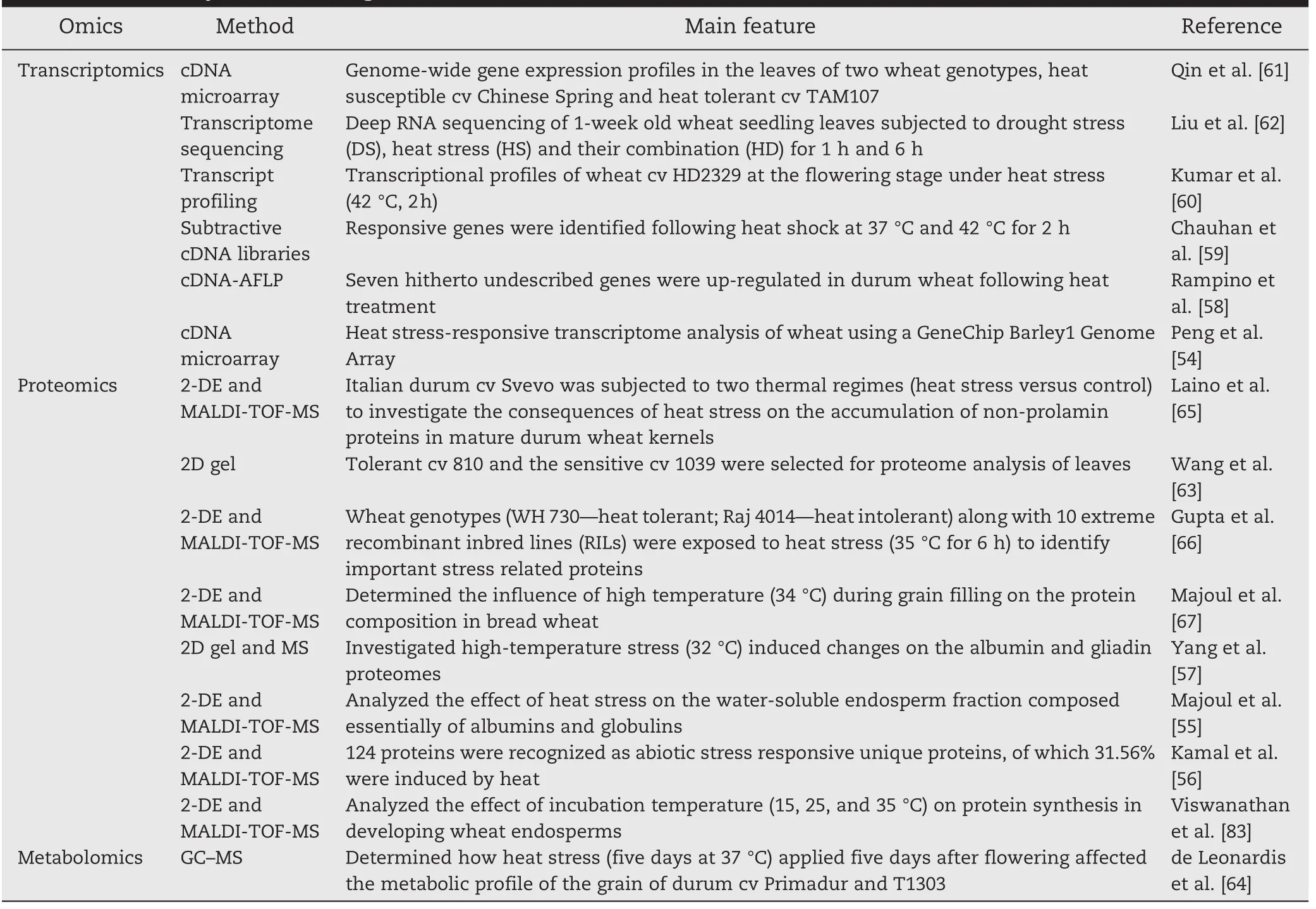

Table 1–Summary of functional genomics studies of heat tolerance in wheat.

Advances in the development of molecular markers and quantitative genetics provided powerful tools for identifying QTL influencing heat tolerance in wheat.Many QTL with significant effects on heat tolerance were detected by using different traits as indicators of tolerance(Table S1)[33–41].By QTL meta-analysis Acu?a-Galindo et al.[42]identified eight major QTL clusters associated with drought and heat tolerance on chromosomes 1B,2B,2D,4A,4B,4D,5A,and 7A.This demonstrated that fine mapping techniques could be applied to identify genes in those regions.Consistent with the earlier studies using chromosome substitution lines,many QTL controlling heat tolerance were located on chromosome 3B[36–39].For example,Mason et al.[36]identified an important QTL region on chromosome 3B associated with heat susceptibility index of yield components by using a recombinant inbred line(RIL)population derived from Halberd and Cutter.Two key QTL on chromosome 3B for canopy temperature and grain yield were detected by Bennett et al.[37]using a set of 255 doubled haploid(DH)lines.Mondal et al.[38]also mapped important QTL influencing canopy temperature on chromosome 3B.More recently,Thomelin et al.[39]mapped a drought and heat tolerance related QTL,qDHY.3BL,in an~1 Mbp interval on chromosome 3B,which contained 22 genes.Recently published sequencing information will be of great benefit for map-based cloning of major QTL controlling heat tolerance[43–47].

Genome-wide association study(GWAS)has been thoroughly proven to be a powerful approach for identifying genes underlying complex traits.GWAS has also been used to dissect the genetic basis of heat tolerance in wheat[48,49].Valluru et al.[40]investigated genotypic variation in ethylene production in spikes(SET)and the relationship of ethylene levels with spike dry weight(SDW)in 130 diverse elite wheat lines and landraces under heat-stressed field conditions.SET was negatively correlated with SDW and the GWAS uncovered 5 and 32 significant SNPs for SET and 22 and 142 significant SNPs for SDW in glasshouse and field conditions,respectively.The phenotypic and genetic elucidation of SET and its relationship with SDW paved a way to breed wheat cultivars with reduced ethylene effects on yield under heat stress.

5.Functional genes for heat tolerance and their regulators

Heat stress swiftly alters the expression pattern of heat-related genes[50–53].In recent years,there has been increasing interest in using functional genomics tools,such as transcriptomics,proteomics,and metabolomics,to identify and understand the components of heat stress tolerance and underlying mechanisms at the molecular level[54–67].The roles of these omics in heat stress tolerance are summarized in Table 1.

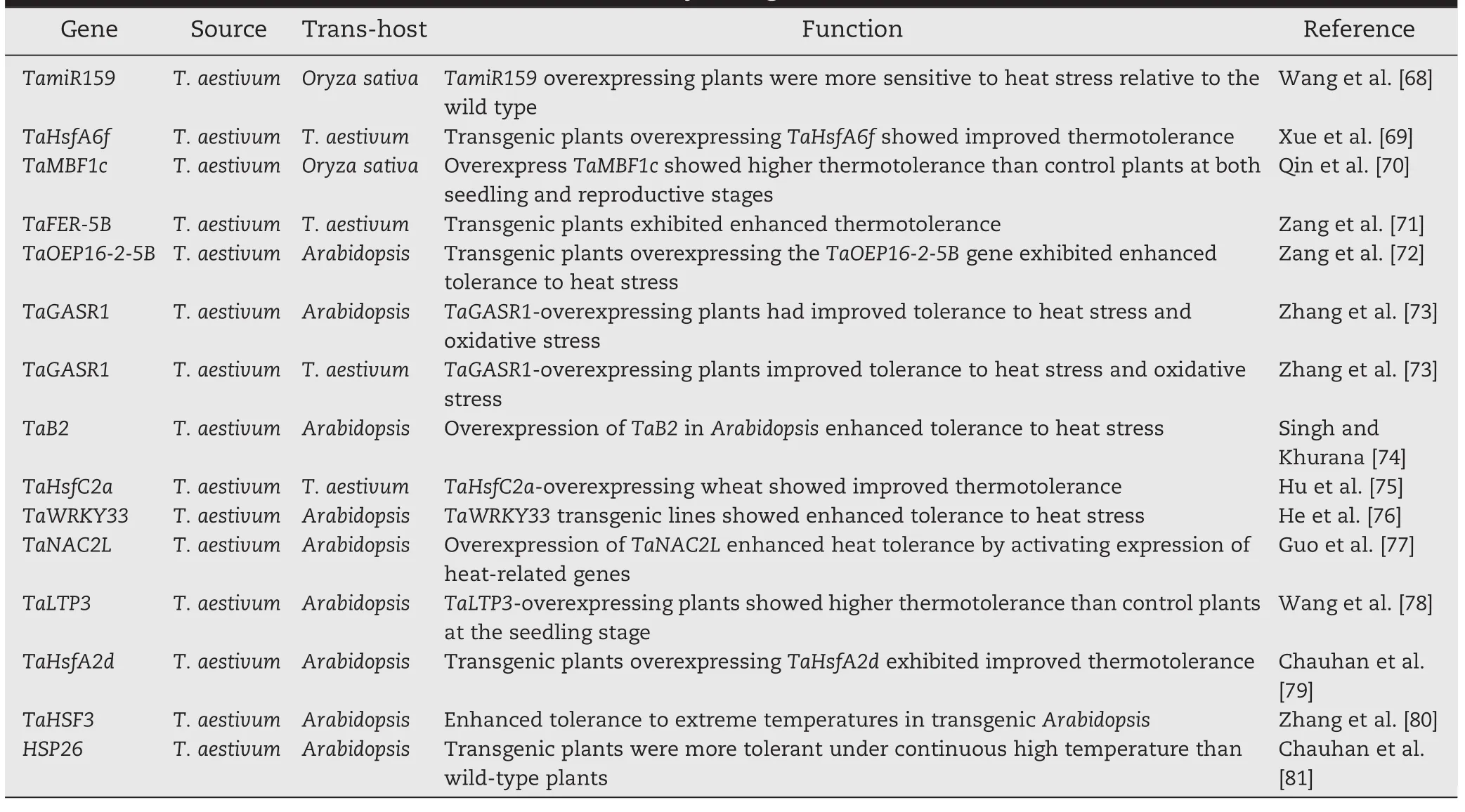

Heat shock proteins(HSPs)function as molecular chaperones in maintaining homeostasis of protein folding and are related to the acquisition of thermotolerance[54–60].The effects of genes encoding HSPs are the most studied molecular responses under heat stress.With the complexity of the underlying mechanisms of heat tolerance,genome wide analysis proved to be a valuable method for identifying genes responsive to heat stress[57–63].In a pioneering study a microarray was used to perform comparative gene expression analysis in leaves of heat-susceptible cv Chinese Spring and heat-tolerant cv TAM107.There were different gene expression patterns between the genotypes following both short and prolonged heat treatments.The heat-responsive genes identified included a large number of important factors involved in a range of biological pathways.This observation facilitated an understanding of the molecular basis of heat tolerance in different wheat genotypes[61].To survive adverse effects of different environmental stresses,plants have evolved special mechanisms and undergone a series of physiological changes.Liu et al.[62] performed high-throughput transcriptome sequencing of wheat seedlings under normal conditions and subjected them to drought stress(DS),heat stress(HS),and their combination(HD)to explore transcriptional responses to individual and combined stresses.Gene Ontology(GO)enrichment analysis of DS,HS,and HD responsive genes revealed an overlapping complexity of functional pathways.In addition,the functions of some wheat genes involved in sensing and responding to heat stress were characterized by overexpression in Arabidopsis or wheat[68–81](Table 2).For example,improved thermotoler-ance was observed in wheat plants over-expressing gene TaHSFA6f[69].Ectopic expression of wheat TaMBF1c,TaFER-5B,TaOEP16-2-5B,TaB2,and TaGASR1 in Arabidopsis could enhance thermotolerance in that species[70–74].Recent improvements in wheat transformation technology and the availability of bread wheat and durum mutant libraries will accelerate progress in functional analysis of heat-responsive genes in wheat[43–47,82].

Sensitive and accurate proteome analysis techniques have emerged as powerful tools in discovering proteins involved in heat stress response[55–57,65–67].To determine the influence of high temperature during grain filling on protein composition in bread wheat,the grain proteome was analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis(2-DE)and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry(MALDI-TOF-MS).Of the total mature wheat grain protein spots,37 were identified as significantly changed by heat treatment.Wheat cultivars grown in warmer areas generally share related characteristics,such as reduced grain weight and higher dough extensibility,than those grown in cooler areas.An interesting finding from proteomic analysis was that one of the first identified enzymes in starch synthesis,glucose-1-phosphate adenyltransferase,was significantly decreased after heat treatment,providing further evidence that starch synthesis is highly sensitive to high temperature stress[67].It is well known that gliadins and glutenins are associated with dough extensibility and elasticity,respectively.Several gliadins were increased after heat stress,whereas glutenins were not affected,indicating that glutenins synthesis is less heat sensitive than gliadin accumulation[83].In another study,47 non-prolamin proteins were differentially expressed under heat stress,including enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism,heat shock proteins,and some defense-related proteins[65].Recent,proteome studies of response to heat stress in flag leaves during the grain filling stage revealed increases in proteins related to signaling transduction,heat shock protein,photosynthesis,antioxidant enzymes,ATP synthase,and GAPDH in conjunction with decreases in proteins related to nitrogen metabolism in the tolerant cv 810 compared to sensitive cv 1039.Collectively,these data revealed that global changes in gene expression after heat stress were reflected by changes at the level of various enzymes and/or proteins involved in different metabolic pathways[63].

Table 2–Genes confirmed to function in heat tolerance by transgenic studies.

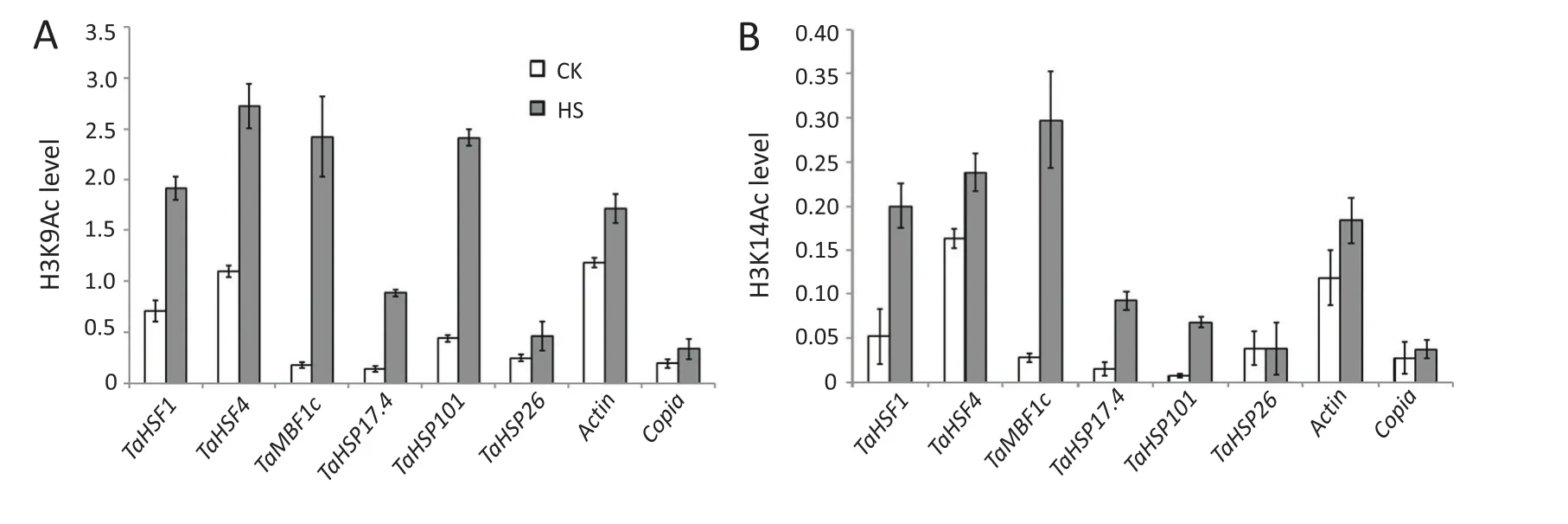

Fig.1–H3K9 and H3K14 acetylation states of the TaHSF1,TaHSF4,TaMBF1c,TaHSP17.4,TaHSP26 and TaHSP101 genes in wheat seedlings before and after heat stress.ChIP analysis of relative enrichment of acetyl-H3K9(A)and acetyl-H3K14(B)at the indicated gene regions.Ten-day-old seedlings that were untreated(CK)or treated at 40°C for 1 h(HS)were analyzed.Signals are given as percentages of the input chromatin value.Mean values and standard deviations are from two independent experiments.

Metabolomics is an important functional genomics tool for understanding plant response to heat stress[84].Knowledge about the role of metabolites in stress tolerance processes is essential for crop species improvement.However,there is only one report of metabolic profiling of heat stress tolerance in wheat.de Leonardis et al.[64]reported that a 5-day heat stress(37°C)after flowering affected the metabolic profiles of durum wheats.This response to heat stress was genotype-dependent,with most analyzed metabolites increased in cv Primadur(high in seed carotenoids),and decreased in cv T1303(high in seed anthocyanin).

6. Major photohormones influencing heat tolerance

Phytohormones play central roles in the ability of plants to adapt to different environments by mediating growth,development,nutrient allocation,and source/sink transitions[85,86].Growing evidence shows that the plant hormone abscisic acid(ABA)has an important role in regulation of heat tolerance in wheat.Firstly,a wheat ABA-insensitive genetic variant had higher kernel weight and yield compared to its parental line[87].Secondly,wheat plants grown at a higher temperature(25 °C compared to 15 °C)accumulated substantially higher ABA concentrations in the grain[88].Thirdly,exogenous ABA improved grain yield by increasing the grain sink capacity and grain filling rate through regulating endogenous hormone contents to promote endosperm cell division and photosynthate accumulation in both normal and high temperature stress conditions[89].Finally,expression of some key genes responsive to heat stress was up-regulated after ABA treatment,such as TaHSP101B and TaHSP101C[90].In addition,ethylene has been linked to a yield penalty underheatstress;lowerspike-ethylene contents were strongly associated with higher grain yield[40].Despite recent advances in our understanding of hormone regulation involved in heat stress response in wheat,many questions remain to be solved in future studies.One of the most important questions is to dissect the underlying interplay of different hormones in response to heat stress.

7.Epigenetics and heat tolerance

Epigenetics is defined as heritable changes in gene activity and expression that occur without alteration in DNA sequence,and is associated with DNA methylation,histonemodification and non-protein coding RNAs[91].Epigenetic regulation of heat responses has attracted increasing interest[92,93].Our research indicated that histone acetyltransferase GENERAL CONTROL OF NONREPRESSED PROTEIN5(GCN5)plays a key role in preservation of thermotolerance by facilitating H3K9 and H3K14 acetylation of heat shock factor A3(HSFA3)and UV-HYPERSENSITIVE6(UVH6)under heat stress in Arabidopsis.We found that the histone acetyltransferase TaGCN5 gene in wheat is upregulated under heat stress and that it functions similarly to GCN5 in Arabidopsis.Hyperacetylation of histones relaxes chromatin structure and is associated with transcriptional activation.We further examined H3K9 and H3K14 acetylation levels in the promoters of six well-known heat-induced and unregulated genes,including TaHSF1,TaHSF4,TaMBF1c,TaHSP17.4,TaHSP26,andTaHSP101,afterheatstress.ChIPassays performed on 10-day-old wheat seedlings under normal conditions and heat stress treatment(1 h at 40°C).As shown in Fig.1,except for the TaHSP26 gene,acetylation levels of H3K9 and H3K14 in the promoters of TaHSF1,TaHSF4,TaMBF1c,TaHSP17.4,and TaHSP101 were significantly enhanced in wheat in response to heat stress.Recently,a genome-wide survey of hexaploid wheat showed that temperature had a dramatic effect on gene expression,but there were only minor differences in methylation patterns between plants grown at 12 °C and 27 °C.However,in only a few cases was methylation associated with small changes in gene expression[93].These preliminary results indicating that histone acetylation and DNA methylation was correlated with alterations in heat stress responsive genes in wheat deserve further investigation.

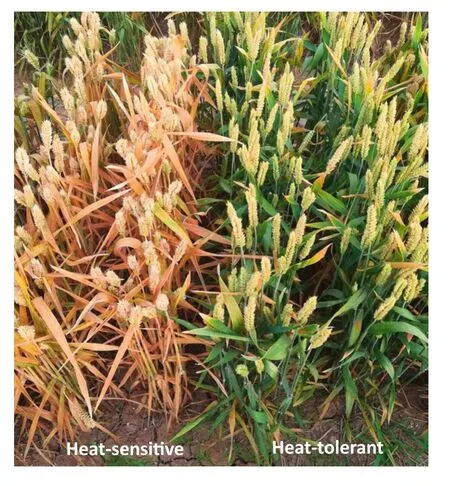

Fig.2–Examples of heat-sensitive and heat-tolerant genotypes after heat stress under field conditions at Linfen in Shanxi province in 2017.

Recent studies suggest that most of the genome is transcribed,but among transcripts only a small portion encode proteins.The larger proportion of transcripts that do not encode proteins are generally termed non-protein coding RNAs(npcRNA).These npcRNAs are subdivided as housekeeping npcRNAs(such as transfer and ribosomal RNAs)and regulatory npcRNAs or riboregulators,with the latter being further divided into short regulatory npcRNAs(<300 bp in length,such as microRNA,siRNA,piwi-RNA)and long regulatory npcRNAs(>300 bp in length)[60,94–97].By using computational analysis and an experimental approach Xin et al.[95]identified 66 heat stress-responsive long npcRNAs that executed their functions in the form of long molecules.To test whether miRNAs have roles in regulating response to heat stress in wheat,Xin et al.[96]cloned small RNA from wheat leaves exposed to heat stress and found that 12 of the 153 miRNAs identified were responsive to heat stress.Kumar etal.[60]identified 37novelmiRNAsin T.aestivum and validated six of the identified novel mi RNA as heat-responsive.Analysis of the pre-miRNAs differentially expressed in response to heat treatment identified 12 and 25 miRNA in durum wheat cv Cappelli and Ofanto,respectively[97].Interestingly,TamiR159 was downregulated after 2 h of heat stress treatment in wheat,but TamiR159 overexpressing rice lines were more sensitive to heat stress relative to the wild type,indicating that downregulation of TamiR159 in wheat after heat stress might participate in a heat stress-related signaling pathway,in turn contributing to heat stress tolerance[68].

8.Breeding for heat tolerance

An index for evaluating heat stress is a major requirement for traditional breeding.Stable yield performance of genotypes under heat stress conditions is vital to identify heat tolerant genotypes.Thus,the relative performance of yield traits under heat-stressed and non-stressed environments has been widely used as an indicator to identify heat-tolerant wheat genotypes[36,98,99].This heat susceptibility index was shown to be a reliable indicator of yield stability and a proxy for heattolerance[33].As forheat treatments,wheat genotypes are generally tested across space and time by manipulation of date of sowing or choosing specific sites for field tests[36,100].Alternatively,heat stress can also be simulated under plastic film covered shelters[38,100].Membrane thermostability and chlorophyll fluorescence were also used as indicators of heat-stress tolerance in wheat,as they showed strong genetic correlations with grain yield[41].

Exploration and utilization of novel genetic variation is the priority for genetic improvement of heat tolerance in wheat breeding programs.In a study of>1200 Mexican wheat landraces collected from areas with diverse thermal regimes,a highly significant correlation between leaf chlorophyll content and thousand grain weight was observed and a group of superior accessions were identified[101].In China,some heat tolerant cultivars/lines have also been identified,and these can be used to develop new cultivars with enhanced heat tolerance(Fig.2).Populations of wild species frequently harbor high intra-species variation for tolerance traits that are superior to what is available in the modern cultivars [102,103].Indeed.Triticum dicoccoides and T.monococcum have been reported as potential sources of germplasms that can be used to enhance heat tolerance in bread wheat.Additionally,variable degrees of heat tolerance were observed in Aegilops speltoides,Ae.longissima and Ae.searsii[104].However,only a small portion of the reported genetic variation in heat tolerance has been utilized due to limitations of conventional breeding methods.

Mapping QTL linked to heat stress tolerance traits will help in developing wheat cultivars suitable for high-temperature environments using marker-assisted selection(MAS)[33].QTL can be categorized into two groups according to the stability of effect across environments:a “constitutive”QTL is consistently detected across environments;whereas an “adaptive”QTL is detected only under specific environmental conditions[105,106].An important prerequisite for a successful MAS program aimed at improving heat tolerance is identification of constitutive QTL.Recently,timely and late so wings were used to map QTL associated with heat tolerance and constitutive QTL were detected on chromosomes 2B and 7B[33].Applying this method we identified one favorable and environmentally stable QTL allele on chromosome 5DL controlling kernel weight in cv Fu 4185,a gamma radiation-induced by mutant of elite wheat cv Shi 4185[107].Considering the severe effect of heat stress on kernel weight in wheat production,selection of QTL associated with kernel weight under high temperature stressmay improve wheat yield potential.

An alternative strategy of improving heat tolerance is transgenesis that enables the transfer of superior genes to elite wheat cultivars,avoiding the problem of linkage drag involving cotransference of unwanted adjacent gene segments[108],or enabling exploitation of genes not accessible through hybridization-based breeding.For example,maize phosphoenol-pyruvate carboxylase gene ZmPEPC overexpressed in wheat enhanced photochemical and antioxidant enzyme activities,upregulated expression of photosynthesis-related genes,delayed chlorophyll degradation,altered contents of proline and other metabolites,and ultimately improved heat tolerance[109].Transgenic wheat with maize EFTu1 gene overexpression also had improved tolerance to high temperature stress[110].

9.Conclusion and remarks

Heat stress is a major cause of yield loss and numbers and duration of heat events are projected to increase in the future.Heat stress has become a major limiting factor in wheat production,because wheat is very sensitive to heat stress,especially at the reproductive and early grain filling stages[111].Heat tolerance is a polygenic trait that is difficult to quantify.Until now,no direct method was available to select heat tolerant plants,but some traits like canopy temperature depression and membrane thermo-stability appear to be effective indicators of plant heat tolerance,and can be used in conventional breeding[42].

Understanding the underlying mechanisms of heat tolerance in wheat is crucial to effectively address how heat stress affects wheat yield and quality,and to provide useful markers and genes for genetic improvement.Various mapping approaches and genetic studies have contributed greatly to a better understanding of the genetic bases of heat stress-tolerance in wheat[37–42].Molecular markers found to be associated with heat tolerance in these studies could be used for MAS.However,there are few reports of molecular markers being utilized in wheat breeding programs[112].On the other hand, increasing knowledge about molecular mechanisms of heat tolerance is likely to pave the way for engineering plants with satisfactory economic yields under heat stress.Although several genes have been successfully engineered in wheat to enhance tolerance to heat stress their function in different genetic backgrounds and under different heat stress conditions is still to be investigated.

Supplementary data for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2017.09.005.

Acknowledgments

The PI's laboratory is supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China(2016YFD0101802,2016YFD0100600)and the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31561143013).We thank Aijun Zhao(Hebei Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences)and Chaofeng Fan(China Agricultural University)for reference preparation and manuscript writing,and Dr.Jun Zheng(Shanxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences)for kindly providing thephotograph thatcomparesheat-sensitive and heat-tolerant genotypes following heat stress under field conditions.

R E F E R E N C E S

[1]I.F.Wardlaw,I.A.Dawson,P.Munibi,R.Fewster,The tolerance of wheat to high temperatures during reproductive growth.I.Survey procedures and general response patterns,Aust.J.Agric.Res.40(1989)965–980.

[2]J.Hansen,M.Sato,R.Ruedy,Perception of climate change,Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.109(2012)E2415–E2423.

[3]M.Moriondo,C.Giannakopoulos,M.Bindi,Climate change impact assessment:the role of climate extremes in crop yield simulation,Clim.Chang.104(2011)679–701.

[4]M.A.Semenov,P.R.Shewry,Modelling predicts that heat stress,not drought,will increase vulnerability of wheat in Europe,Sci Rep 1(2011)66.

[5]D.Gouache,B.X.Le,M.Bogard,O.Deudon,C.Pagé,P.Gate,Evaluating agronomic adaptation options to increasing heat stress under climate change during wheat grain filling in France,Eur.J.Agron.39(2012)62–70.

[6]D.B.Lobell,C.B.Field,Global scale climate-crop yield relationships and the impacts of recent warming,Environ.Res.Lett.2(2007)14–21.

[7]B.Zheng,K.Chenu,D.M.Fernanda,S.C.Chapman,Breeding for the future:what are the potential impacts of future frost and heat events on sowing and flowering time requirements for Australian bread wheat(Triticum aestivium)varieties?Glob.Change Biol.18(2012)2899–2914.

[8]E.I.Teixeira,G.Fischer,H.V.Velthuizen,C.Walter,F.Ewert,Global hot-spots of heat stress on agricultural crops due to climate change,Agric.For.Meteorol.170(2013)206–215.

[9]J.Larkindale,M.R.Knight,Protection against heat stressinduced oxidative damage in Arabidopsis involves calcium,abscisic acid,ethylene,and salicylic acid,Plant Physiol.128(2002)682–695.

[10]X.Liu,B.Huang,Heat stress injury in relation to membrane lipid peroxidation in creeping bentgrass,Crop Sci.40(2000)503–510.

[11]C.M.Cossani,M.P.Reynolds,Physiological traits for improving heat tolerance in wheat,Plant Physiol.160(2012)1710–1718.

[12]N.H.Shah,G.M.Paulsen,Interaction of drought and high temperature on photosynthesis and grain-filling of wheat,Plant Soil 257(2003)219–226.

[13]Z.Ristic,U.Bukovnik,P.V.V.Prasad,Correlation between heat stability of thylakoid membranes and loss of chlorophyll in winter wheat under heat stress,Crop Sci.47(2007)2067–2073.

[14]Z.Ristic,U.Bukovnik,I.Mom?ilovi?,J.M.Fu,P.V.V.Prasad,Heat-induced accumulation of chloroplast protein synthesis elongation factor,EF-Tu,in winter wheat,Aust.J.Plant Physiol.165(2008)192–202.

[15]P.L.Keeling,P.J.Bacon,D.C.Holt,Elevated temperature reduces starch deposition in wheat endosperm by reducing the activity of soluble starch synthase,Planta 191(1993)342–348.

[16]C.F.Jenner,Starch synthesis in the kernel of wheat under high temperature conditions,Funct.Plant Biol.21(1994)791–806.

[17]P.J.Stone,M.E.Nicolas,Effect of timing of heat stress during grain filling on two wheat varieties differing in heat tolerance.I.Grain growth,Austr.J.Plant Physiol.22(1995)927–934.

[18]P.V.V.Prasad,S.A.Staggenborg,Z.Ristic,Impacts of drought and/or heat stress on physiological,developmental,growth,and yield processes of crop plants,in:L.R.Ahuja,V.R.Reddy,S.A.Saseendran,Q.Yu(Eds.),Response of Crops to Limited Water:Understanding and Modeling Water Stress Effects on Plant Growth Processes,Advances in Agricultural Systems Modeling 1:Transdisciplinary Research,Synthesis,and Applications,American Society of Agronomy,Crop Science Society of America,Soil Science Society of America,Madison,WI,USA 2008,pp.301–355.

[19]X.Yang,X.Tang,B.Chen,Z.Tian,H.Zhong,Impacts of heat stress on wheat yield due to climatic warming in China,Prog.Geogr.32(2013)1771–1779.

[20]D.B.Lobell,A.Sibley,J.I.Ortizmonasterio,Extreme heat effects on wheat senescence in India,Nat.Clim.Chang.2(2012)186–189.

[21]J.H.J.Spiertz,R.J.Hamer,H.Xu,C.Primomartin,C.Don,P.Pelvander,Heat stress in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.):effects on grain growth and quality traits,Eur.J.Agron.25(2006)89–95.

[22]B.Borghi,M.Corbellini,M.Ciaffi,D.Lafiandra,E.Stefanis,D.Sgrulletta,G.Boggini,N.Fonzo,S.E.De,F.N.Di,Effect of heat shock during grain filling on grain quality of bread and durum wheats,Aust.J.Agric.Res.46(1995)1365–1380.

[23]X.Qin,F.Zhang,C.Liu,H.Yu,B.Cao,S.Tian,Y.Liao,K.H.M.Siddique,Wheat yield improvements in China:past trends and future directions,Field Crops Res.177(2015)117–124.

[24]B.Liu,L.Liu,L.Tian,W.Cao,Y.Zhu,S.Asseng,Post-heading heat stress and yield impact in winter wheat of China,Glob.Change Biol.20(2014)372–381.

[25]X.Yang,Z.Tian,L.Sun,B.Chen,F.N.Tubiello,Y.Xu,The impacts of increased heat stress events on wheat yield under climate change in China,Clim.Chang.140(2017)605.

[26]Y.Li,W.Zhang,L.Ma,L.Wu,J.Shen,W.J.Davies,O.Oenema,F.Zhang,Z.Dou,An analysis of China's grain production:looking back and looking forward,Food Energy Secur.3(2014)19–32.

[27]L.Ye,H.Tang,W.Wu,P.Yang,G.C.Nelson,D.Mason-D'Croz,A.Palazzo,Chinese food security and climate change:agriculture futures,Econ.Discuss.Pap.8(2014)1–39.

[28]C.Howarth,Genetic improvements of tolerance to high temperature,in:M.Ashraf,P.J.C.Harris(Eds.),Abiotic Stresses–Plant Resistance Through Breeding and Molecular Approaches,The Haworth Press,New York,USA 2005,pp.277–300.

[29]H.J.Bohnert,Q.Gong,P.Li,S.Ma,Unraveling abiotic stress tolerance mechanisms–getting genomics going,Curr.Opin.Plant Biol.9(2006)180–188.

[30]Q.X.Sun,J.S.Quick,Chromosomal locations of genes for heat tolerance in tetraploid wheat,Cereal Res.Commun.19(1991)431–437(in Chinese with English abstract).

[31]R.Xu,Q.Sun,S.Zhang,Chromosomal location of genes for heat tolerance as measured by membrane thermostability of common wheat cv.Hope,Hereditas 18(1996)1–3(in Chinese with English abstract).

[32]X.Y.Chen,A.J.Zhao,Y.J.Li,Y.P.Liu,Acta Agric.Boreali-Sin.22(S2)(2007)1–5(in Chinese with English abstract).

[33]R.Paliwal,M.S.R?der,U.Kumar,J.P.Srivastava,A.K.Joshi,QTL mapping of terminal heat tolerance in hexaploid wheat(T.aestivum L.),Theor.Appl.Genet.125(2012)561–575.

[34]S.P.Li,X.P.Chang,C.S.Wang,R.L.Jing,Mapping QTL for heat tolerance at grain filling stage in common wheat,Sci.Agric.Sin.46(2013)2119–2129(in Chinese with English abstract).

[35]S.P.Li,X.P.Chang,C.S.Wang,R.L.Jing,Mapping QTLs for seedling traits and heat tolerance indices in common wheat,Acta Bot.Boreali-Occidential Sin.32(2012)1525–1533.

[36]R.E.Mason,S.Mondal,F.W.Beecher,A.Pacheco,B.Jampala,A.M.H.Ibrahim,D.B.Hays,QTL associated with heat susceptibility index in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)under short-term reproductive stage heat stress,Euphytica 174(2010)423–436.

[37]D.Bennett,M.Reynolds,D.Mullan,A.Izanloo,H.Kuchel,P.Langridge,T.Schnurbusch,Detection of two major grain yield QTL in bread wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)under heat,drought and high yield potential environments,Theor.Appl.Genet.125(2012)1473–1485.

[38]S.Mondal,R.E.Mason,T.Huggins,D.B.Hays,QTL on wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)chromosomes 1B,3D and 5A are associated with constitutive production of leaf cuticular wax and may contribute to lower leaf temperatures under heat stress,Euphytica 201(2015)123–130.

[39]P.Thomelin,J.Bonneau,J.Taylor,F.Choulet,P.Sourdille,P.Langridge,Positional cloning of a QTL,qDHY.3BL,on chromosome 3BL for drought and heat tolerance in bread wheat,Proceedings of the Plant and Animal Genome Conference(PAGXXIV),January 9–13,2016,San Diego,CA,USA,2016.

[40]R.Valluru,M.P.Reynolds,W.J.Davies,S.Sukumaran,Phenotypic and genome-wide association analysis of spike ethylene in diverse wheat genotypes under heat stress,New Phytol.214(2017)271–283.

[41]S.K.Talukder,M.A.Babar,K.Vijayalakshmi,J.Poland,P.V.V.Prasad,R.Bowden,A.Fritz,Mapping QTL for the traits associated with heat tolerance in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),BMC Genet.15(2014)1–13.

[42]M.A.Acu?agalindo,R.E.Mason,N.K.Subramanian,D.B.Hays,Meta-analysis of wheat QTL regions associated with adaptation to drought and heat stress,Crop Sci.55(2015)477–492.

[43]B.J.Clavijo,L.Venturini,C.Schudoma,G.G.Accinelli,G.Kaithakottil,J.Wright,P.Borrill,G.Kettleborough,D.Heavens,H.Chapman,An improved assembly and annotation of the allohexaploid wheat genome identifies complete families of agronomic genes and provides genomic evidence for chromosomal translocations,Genome Res.27(2017)885–896.

[44]R.Brenchley,M.Spannagl,M.Pfeifer,G.L.Barker,R.D'Amore,A.M.Allen,N.Mckenzie,M.Kramer,A.Kerhornou,D.Bolser,Analysis of the bread wheat genome using wholegenome shotgun sequencing,Nature 491(2012)705–710.

[45]J.A.Chapman,M.Mascher,A.Bulu?,K.Barry,E.Georganas,A.Session,V.Strnadova,J.Jenkins,S.Sehgal,L.Oliker,A whole-genome shotgun approach forassembling and anchoring the hexaploid bread wheat genome,Genome Biol.16(2015)26.

[46]F.Choulet,A.Alberti,S.Theil,N.Glover,V.Barbe,J.Daron,L.Pingault,P.Sourdille,A.Couloux,E.Paux,P.Leroy,S.Mangenot,N.Guilhot,J.Le Gouis,F.Balfourier,M.Alaux,V.Jamilloux,J.Poulain,C.Durand,A.Bellec,C.Gaspin,J.Safar,J.Dolezel,J.Rogers,K.Vandepoele,J.M.Aury,K.Mayer,H.Berges,H.Quesneville,P.Wincker,C.Feuillet,Structural and functional partitioning of bread wheat chromosome 3B,Science 345(2014)1249721.

[47]The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium(IWGSC),A chromosome-based draft sequence of the hexaploid bread wheat(Triticum aestivum)genome,Science 345(2014)1251788.

[48]F.Tian,P.J.Bradbury,P.J.Brown,H.Hung,Q.Sun,S.Flint-Garcia,T.R.Rocheford,M.D.McMullen,J.B.Holland,E.S.Buckler,Genome-wide association study of leaf architecture in the maize nested association mapping population,Nat.Genet.43(2011)159–162.

[49]X.H.Huang,Y.Zhao,X.H.Wei,C.Y.Li,A.H.Wang,Q.Zhao,W.J.Li,Y.L.Guo,L.W.Deng,C.R.Zhu,D.L.Fan,Y.Q.Lu,Q.J.Weng,K.Y.Liu,T.Y.Zhou,Y.F.Jing,L.Z.Si,G.J.Dong,T.Huang,T.T.Lu,Q.Feng,Q.Qian,J.Y.Li,B.Han,Genomewide association study of flowering time and grain yield traits in a worldwide collection of rice germplasm,Nat.Genet.44(2012)32.

[50]C.E.Bita,T.Gerats,Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment:scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops,Front.Plant Sci.4(2013)273.

[51]J.Zhuang,J.Zhang,X.L.Hou,F.Wang,A.S.Xiong,Transcriptomic,proteomic,metabolomic and functional genomic approaches for the study of abiotic stress in vegetable crops,Crit.Rev.Plant Sci.33(2014)225–237.

[52]E.Yángüez,A.B.Castro-Sanz,N.Fernández-Bautista,J.C.Oliveros,M.M.Castellano,Analysis of genome-wide changes in the translatome of Arabidopsis seedlings subjected to heat stress,PLoS One 8(2013)e71425.

[53]N.Gonzálezschain,L.Dreni,L.M.Lawas,M.Galbiati,L.Colombo,S.Heuer,K.S.Jagadish,M.M.Kater,Genome-wide transcriptome analysis during anthesis reveals new insights in the molecular basis of heat stress responses in tolerant and sensitive rice varieties,Plant Cell Physiol.57(2016)57.

[54]D.Peng,H.Peng,Z.Ni,X.Nie,Y.Yao,D.Qin,K.He,Q.Sun,Heat stress-responsive transcriptome analysis of wheat by using GeneChip Barley1 Genome Array,Prog.Nat.Sci.16(2006)1379–1387.

[55]T.Majoul,E.Bancel,E.Tribo?,H.J.Ben,G.Branlard,Proteomic analysis of the effect of heat stress on hexaploid wheat grain:characterization of heat-responsive proteins from non-prolamins fraction,Proteomics 4(2004)505–513.

[56]A.H.M.Kamal,K.Kihyun,S.Kwanghyun,C.Jongsoon,B.Byungkee,H.Tsujimoto,H.Hwayoung,P.Chulsoo,W.Sunhee,Abiotic stress responsive proteins of wheat grain determined using proteomics techniques,Aust.J.Crop.Sci.4(2010)196–208.

[57]F.Yang,A.D.J?rgensen,H.Li,I.S?ndergaard,C.Finnie,B.Svensson,D.Jiang,B.Wollenweber,S.Jacobsen,Implications of high-temperature events and water deficits on protein profiles in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.cv.Vinjett)grain,Proteomics 11(2011)1684–1695.

[58]P.Rampino,G.Mita,P.Fasano,G.M.Borrelli,A.Aprile,G.Dalessandro,B.L.De,C.Perrotta,Novel durum wheat genes up-regulated in response to a combination of heat and drought stress,Plant Physiol.Biochem.56(2012)72–78.

[59]H.Chauhan,N.Khurana,A.K.Tyagi,J.P.Khurana,P.Khurana,Identification and characterization of high temperature stress responsive genes in bread wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)and their regulation at various stages of development,Plant Mol.Biol.75(2011)35–51.

[60]R.R.Kumar,H.Pathak,S.K.Sharma,Y.K.Kala,M.K.Nirjal,G.P.Singh,S.Goswami,R.D.Rai,Novel and conserved heatresponsive microRNAs in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),Funct.Integr.Genomics 15(2015)323–348.

[61]D.Qin,H.Wu,H.Peng,Y.Yao,Z.Ni,Z.Li,C.Zhou,Q.Sun,Heat stress-responsive transcriptome analysis in heat susceptible and tolerant wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)by using Wheat Genome Array,BMC Genomics 9(2008)432.

[62]Z.Liu,M.Xin,J.Qin,H.Peng,Z.Ni,Y.Yao,Q.Sun,Temporal transcriptome profiling reveals expression partitioning of homeologous genes contributing to heat and drought acclimation in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),BMC Plant Biol.15(2015)1–20.

[63]X.Wang,B.S.Dinler,M.Vignjevic,S.Jacobsen,B.Wollenweber,Physiological and proteome studies of responses to heat stress during grain filling in contrasting wheat cultivars,Plant Sci.230(2015)33–50.

[64]D.L.A.Maria,F.Mariagiovanna,B.Romina,F.D.B.Maria,D.V.Pasquale,M.A.Maria,Effects of heat stress on metabolite accumulation and composition,and nutritional properties of durum wheat grain,Int.J.Mol.Sci.16(2015)30382–30404.

[65]P.Laino,D.Shelton,C.Finnie,A.M.D.Leonardis,A.M.Mastrangelo,B.Svensson,D.Lafiandra,S.Masci,Comparative proteome analysis of metabolic proteins from seeds of durum wheat(cv.Svevo)subjected to heat stress,Proteomics 10(2010)2359–2368.

[66]O.P.Gupta,V.Mishra,N.K.Singh,R.Tiwari,P.Sharma,R.K.Gupta,I.Sharma,Deciphering the dynamics of changing proteins of tolerant and intolerant wheat seedlings subjected to heat stress,Mol.Biol.Rep.42(2015)43–51.

[67]T.Majoul,E.E.Bancel,H.J.Ben,G.Branlard,Proteomic analysis of the effect of heat stress on hexaploid wheat grain:characterization of heat-responsive proteins from total endosperm,Proteomics 3(2003)175–183.

[68]Y.Wang,F.Sun,H.Cao,H.Peng,Z.Ni,Q.Sun,Y.Yao,TamiR159 directed wheat taGAMYB cleavage and its involvement in anther development and heat response,PLoS One 7(2012),e48445.

[69]G.P.Xue,J.Drenth,C.L.Mcintyre,TaHsfA6f is a transcriptional activator that regulates a suite of heat stress protection genes in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)including previously unknown Hsf targets,J.Exp.Bot.66(2015)1025–1039.

[70]D.Qin,F.Wang,X.Geng,L.Zhang,Y.Yao,Z.Ni,H.Peng,Q.Sun,Overexpression of heat stress-responsive TaMBF1c,a wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)multiprotein bridging factor,confers heat tolerance in both yeast and rice,Plant Mol.Biol.87(2015)31–45.

[71]X.Zang,X.Geng,F.Wang,Z.Liu,L.Zhang,Y.Zhao,X.Tian,Z.Ni,Y.Yao,M.Xin,Overexpression of wheat ferritin gene TaFER-5B enhances tolerance to heat stress and other abiotic stresses associated with the ROS scavenging,BMC Plant Biol.17(2017)14.

[72]X.Zang,X.Geng,K.Liu,W.Fei,Z.Liu,L.Zhang,Z.Yue,X.Tian,Z.Hu,Y.Yao,Ectopic expression of TaOEP16-2-5B,a wheat plastid outer envelope protein gene,enhances heat and drought stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants,Plant Sci.258(2017)1–11.

[73]L.Zhang,X.Geng,H.Zhang,C.Zhou,A.Zhao,F.Wang,Y.Zhao,X.Tian,Z.Hu,M.Xin,Isolation and characterization of heat-responsive gene TaGASR1 from wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),J.Plant Biol.60(2017)57–65.

[74]A.Singh,P.Khurana,Molecular and functional characterization of a wheat B2 protein imparting adverse temperature tolerance and influencing plant growth,Front.Plant Sci.7(2016)642.

[75]X.J.Hu,D.Chen,C.L.Mclntyre,M.F.Dreccer,Z.B.Zhang,J.Drenth,K.Sundaravelpandian,H.Chang,G.P.Xue,Heat shock factor C2a serves as a proactive mechanism for heat protection in developing grains in wheat via an ABA-mediated regulatory pathway,Plant Cell Environ.(2017),https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12957.

[76]G.H.He,J.Y.Xu,Y.X.Wang,J.M.Liu,P.S.Li,C.Ming,Y.Z.Ma,Z.S.Xu,Drought-responsive WRKY transcription factor genes TaWRKY1 and TaWRKY33 from wheat confer drought and/or heat resistance in Arabidopsis,BMC Plant Biol.16(2016)116.

[77]W.Guo,J.Zhang,N.Zhang,M.Xin,H.Peng,Z.Hu,Z.Ni,J.Du,The wheat NAC transcription factor TaNAC2L is regulated at the transcriptional and post-translational levels and promotes heat stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis,PLoS One 10(2015),e0135667.

[78]F.Wang,X.S.Zang,M.R.Kabir,K.L.Liu,Z.S.Liu,Z.F.Ni,Y.Y.Yao,Z.R.Hu,Q.X.Sun,H.R.Peng,A wheat lipid transfer protein 3 could enhance the basal thermotolerance and oxidative stress resistance of Arabidopsis,Gene 550(2014)18–26.

[79]H.Chauhan,N.Khurana,P.Agarwal,J.P.Khurana,P.Khurana,A seed preferential heat shock transcription factor from wheat provides abiotic stress tolerance and yield enhancement in transgenic Arabidopsis under heat stress environment,PLoS One 8(2013),e79577.

[80]S.Zhang,Z.S.Xu,P.Li,L.Yang,Y.Wei,M.Chen,L.Li,G.Zhang,Y.Ma,Overexpression of TaHSF3 in transgenic Arabidopsis enhances tolerance to extreme temperatures,Plant Mol.Biol.Rep.31(2013)688–697.

[81]H.Chauhan,N.Khurana,A.Nijhavan,J.P.Khurana,P.Khurana,The wheat chloroplastic small heat shock protein(sHSP26)is involved in seed maturation and germination and imparts tolerance to heat stress,Plant Cell Environ.35(2012)1912–1931.

[82]L.J.Gardiner,P.Gawroński,L.Olohan,T.Schnurbusch,N.Hall,A.Hall,Using genic sequence capture in combination with a syntenic pseudo genome to map a deletion mutant in a wheat species,Plant J.80(2014)895–904.

[83]C.Viswanathan,R.Khanna-Chopra,Effect of heat stress on grain growth,starch synthesis and protein synthesis in grains of wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)varieties differing in grain weight stability,J.Agron.Crop Sci.186(2001)1–7.

[84]C.Guy,F.Kaplan,J.Kopka,J.Selbig,D.K.Hincha,Metabolomics of temperature stress,Physiol.Plant.132(2008)220–235.

[85]Z.Peleg,E.Blumwald,Hormone balance and abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants,Curr.Opin.Plant Biol.14(2011)290–295.

[86]G.J.Ahammed,X.Li,J.Zhou,Y.H.Zhou,J.Q.Yu,Role of hormones in plant adaptation to heat stress,in:G.J.Ahammed,J.Q.Yu(Eds.),Plant Hormones Under Challenging Environmental Factors,Springer,Dordrecht,The Netherlands 2016,pp.1–21.

[87]D.B.Lu,R.G.Sears,G.M.Paulsen,Increasing stress resistance by in vitro selection for abscisic acid insensitivity in wheat,Crop Sci.29(1989)939–943.

[88]M.Walker-Simmons,J.Sesing,Temperature effects on embryonic abscisic acid levels during development of wheat grain dormancy,J.Plant Growth Regul.9(1990)51–56.

[89]D.Q.Yang,Z.L.Wang,Y.L.Ni,Y.P.Yin,T.Cai,W.B.Yang,D.L.Peng,Z.Y.Cui,W.W.Jiang,Effect of high temperature stress and spraying exogenous ABA post-anthesis on grain filling and grain yield in different types of stay-green wheat,Sci.Agric.Sin.47(2014)2109–2125(in Chinese with English abstract).

[90]J.L.Campbell,N.Y.Klueva,H.G.Zheng,J.Nietosotelo,T.D.Ho,H.T.Nguyen,Cloning of new members of the heat shock protein HSP101 gene family in wheat(Triticum aestivum(L.)Moench)inducible by heat,dehydration,and ABA,Biochim.Biophys.Acta-Gene Struct.Expr.1517(2001)270–277.

[91]P.A.Crisp,D.Ganguly,S.R.Eichten,J.O.Borevitz,B.J.Pogson,Reconsidering plant memory:intersections between stress recovery,RNA turnover,and epigenetics,Sci.Adv.2(2016)e1501340.

[92]J.Liu,L.Feng,J.Li,Z.He,Genetic and epigenetic control of plant heat responses,Front.Plant Sci.6(2015)267.

[93]L.J.Gardiner,M.Quintontulloch,L.Olohan,J.Price,N.Hall,A.Hall,A genome-wide survey of DNA methylation in hexaploid wheat,Genome Biol.16(2015)273.

[94]C.Charon,A.B.Moreno,F.Bardou,M.Crespi,Non-proteincoding RNAs their interacting RNA-binding proteins in the plant cell nucleus,Mol.Plant 3(2010)729–739.

[95]M.Xin,W.Yu,Y.Yao,S.Na,Z.Hu,D.Qin,C.Xie,H.Peng,Z.Ni,Q.Sun,Identification and characterization of wheat long non-protein coding RNAs responsive to powdery mildew infection and heat stress by using microarray analysis and SBS sequencing,BMC Plant Biol.11(2011)61.

[96]M.Xin,W.Yu,Y.Yao,C.Xie,H.Peng,Z.Ni,Q.Sun,Diverse set of microRNAs are responsive to powdery mildew infection and heat stress in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),BMC Plant Biol.10(2010)123.

[97]L.Giusti,E.Mica,E.Bertolini,A.M.De Leonardis,P.Faccioli,L.Cattivelli,C.Crosatti,microRNAs differentially modulated in response to heat and drought stress in durum wheat cultivars with contrasting water use efficiency,Funct.Integr.Genomics 17(2017)293–309.

[98]A.S.Dias,F.C.Lidon,Evaluation of grain filling rate and duration in bread and durum wheat,under heat stress after anthesis,J.Agron.Crop Sci.195(2009)137–147.

[99]D.Sharma,R.Singh,J.Rane,V.K.Gupta,H.M.Mamrutha,R.Tiwari,Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with grain filling duration and grain number under terminal heat stress in bread wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),Plant Breed.135(2016)538–545.

[100]B.Zhang,W.Li,X.Chang,R.Li,R.Jing,Effects of favorable alleles for water-soluble carbohydrates at grain filling on grain weight under drought and heat stresses in wheat,PLoS One 9(2014),e102917.

[101]A.R.Hede,B.Skovmand,M.P.Reynolds,J.Crossa,A.L.Vilhelmsen,O.St?len,Evaluating genetic diversity for heat tolerance traits in Mexican wheat landraces,Genet.Resour.Crop.Evol.46(1999)37–45.

[102]X.Geng,Y.Zhang,X.Zang,Y.Zhao,J.Zhang,M.You,N.I.Zhongfu,Y.Yao,M.Xin,H.Peng,Evaluation the thermotolerance of the wheat(Triticum aestivum L.)cultivars and advanced lines collected from the northern China and north area of Huang-Huai winter wheat regions,J.Triticeae Crops 36(2016)172–181(in Chinese with English abstract).

[103]P.Rampino,S.Pataleo,C.Gerardi,G.Mita,C.Perrotta,Drought stress response in wheat:physiological and molecular analysis of resistant and sensitive genotypes,Plant Cell Environ.29(2006)2143–2152.

[104]G.P.Pradhan,P.V.V.Prasad,A.K.Fritz,M.B.Kirkham,B.S.Gill,High temperature tolerance in Aegilops species and its potential transfer to wheat,Crop Sci.52(2012)292–304.

[105]M.Vargas,F.A.V.Eeuwijk,J.Crossa,J.M.Ribaut,QTLs Mapping,QTL×environment interaction for CIMMYT maize drought stress program using factorial regression and partial least squares methods,Theor.Appl.Genet.112(2006)1009–1023.

[106]N.C.Collins,F.Tardieu,R.Tuberosa,Quantitative trait loci and crop performance under abiotic stress:where do we stand?Plant Physiol.147(2008)469–486.

[107]X.Cheng,L.Chai,Z.Chen,L.Xu,H.Zhai,A.Zhao,H.Peng,Y.Yao,M.You,Q.Sun,Identification and characterization of a high kernel weight mutant induced by gamma radiation in wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),BMC Genet.16(2015)127.

[108]H.Budak,M.Kantar,K.Y.Kurtoglu,Drought tolerance in modern and wild wheat,Sci.World J.2013(2013)548246.

[109]X.Qi,W.Xu,J.Zhang,G.Rui,M.Zhao,H.Lin,H.Wang,H.Dong,L.Yan,Physiological characteristics and metabolomics of transgenic wheat containing the maize C4phos-phoenolpyruvate carboxylase(PEPC)gene under high temperature stress,Protoplasma 254(2017)1017–1030.

[110]J.Fu,I.Mom?ilovi?,T.E.Clemente,N.Nersesian,H.N.Trick,Z.Ristic,Heterologous expression of a plastid EF-Tu reduces protein thermal aggregation and enhances CO2fixation in wheat(Triticum aestivum)following heat stress,Plant Mol.Biol.68(2008)277–288.

[111]S.Asseng,I.Foster,N.C.Turner,The impact of temperature variability on wheat yields,Glob.Change Biol.17(2011)997–1012.

[112]Y.Xu,J.H.Crouch,Marker-assisted selection in plant breeding:from publications to practice,Crop Sci.48(2008)391–407.

- The Crop Journal的其它文章

- A journey to understand wheat Fusarium head blight resistance in the Chinese wheat landrace Wangshuibai

- The landscape of molecular mechanisms for salt tolerance in wheat

- Wheat genome editing expedited by efficient transformation techniques: Progress and perspectives

- Corrigendum to “A new method for evaluating the drought tolerance of upland rice cultivars”[Crop J. 5 (2017) 488–489]

- Mapping stripe rust resistance genes by BSR-Seq:YrMM58 and YrHY1 on chromosome 2AS in Chinese wheat lines Mengmai 58 and Huaiyang 1 are Yr17

- Wheat breeding in the hometown of Chinese Spring