The Peircean Sign as a Model for Interpreting Semiotic Structures in Mandarin Chinese

Steven Bonta

Abstract The notion that language is a system of signs is explored in the context of Mandarin Chinese. We use the Peircean Sign, derived from the Peircean ontological categories Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness, as an interpretive framework. Because Mandarin Chinese is both well-documented and comparatively opaque to foreign influences, it presents an ideal case study for the formation of semiotic structures based on the operation of a single Peircean Category-sign (in contrast to English, which, with much higher levels of foreign contact-induced change, would be expected to involve a broad mixture of various semiotic influences). We examine semiotic structures in Chinese at the featural/phonological, lexical, and morphosyntactic levels, as well as the inventory of written characters. We conclude that the primary constraint that conditions semiotic structures in Chinese is the Peircean category Firstness of Secondness/[12]. We also show how this conditioning constraint imposes a semiotic and structural consistency across different levels of language, and how it helps to explain certain evolutionary characteristics of Chinese.

Keywords: Charles Sanders Peirce, linguistic semiotics, Chinese linguistics, semiotic structures, semiotics, semiotic systems, Peircean categories

1. Introduction

Since Saussure, the notion that language is “a system of signs that express ideas” has been taken for granted by the community of linguists and semioticians, with scant regard for what the basis of that systematicity might be. Otherwise put, the internal structure of signs themselves, whether qua Saussure’s signifier/signified dyad or Peirce’s Sign/Object/Interpretant triad, has been closely studied, while the notion of an extended semiotic “system” with all of its structural interrelations, which human language is purported to be, has been afforded comparatively scant attention (the work of Hjelmslev being an ambitious exception).

Peirce famously and pithily observed that the “function of conceptions is to reduce the manifold of sensuous impressions to unity, and … the validity of a conception consists in the impossibility of reducing the content of consciousness to unity without the introduction of it” (Peirce, 1992, p. 1). It is the admittedly ambitious aim of this paper to suggest a framework for conceptualizing the systemic aspect of language as a semiotic phenomenon (which concept could be applied, mutatis mutandis, to any sign system, including larger systems by which human language is subsumed, e.g., culture). Given the complexity of any given language, we propose to submit just one, (Mandarin) Chinese, to fairly detailed consideration, in hopes that the systematizing principle will emerge clearly enough from our analysis to inspire similar study in other languages. In previous work (Bonta, 2015, 2018, in press), I have made passing reference to the way in which such a language may be conceptualized within the larger framework of unifying Culture-symbols (i.e., entire cultures qua symbols; languages are prominent parts of these even more luxuriant semiotic wholes); this paper is a first attempt to exhaustively subject a single human language to systematic semiotic analysis.

2. Language as a System of Signs

Hjelmslev’s Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, with its Saussurean analysis of syntax and paradigm and its well-known differentiation of sign from figura, remains the most exhaustive attempt to analyze language, per Saussure’s prescription, as a semiotic system. In so doing, Hjelmslev distinguishes between system (paradigm/language) and process (syntax/text) (Hjelmslev, 1961, p. 39), as also between signs (any meaningful elements of language, such as morphemes) and figurae (any systematic elements of language supposed to be prior to meaning proper, such as phonemes) (Hjelmslev, 1961, pp. 43-47). Such distinctions arise naturally enough from the Saussurean notion of the sign as a discrete unit analyzable as a signifier yoked to some signified, and concatenated, at least in potentia, with other signs in synchronic (paradigmatic) or diachronic (syntagmatic) ensembles. But the exclusion of process from the domain of system, as well as the demarcation of allegedly meaningless figurae from full-fledged signs, would appear to be reductionisms motivated more by Hjelmslev’s aversion to synechism1(an instinct shared by Cartesians in general) than by any adherence to the messy dictates of linguistic (and semiotic) reality. In reality, differences between sign and non-sign, between meaningful and meaningless structure, are differences of degree and not of essence.

In a gentle rebuttal to Hjelmslev’s figurae, the ever-perceptive Jakobson noted that, even with the primordial elements of language, the distinctive features that differentiate phonemes, there is an element, however inchoate, of signification—“mere otherness” (see, e.g., discussion in Andrews, 2012, p. 217).

In moving from more to less elemental levels of language, we find at every pass order and systematization, but never a bright line where language passes abruptly from meaninglessness to signification. In moving from distinctive features and phonemes upwards through morphemes, sentences, and ultimately to complex texts, we find instead a gradual progression from inchoate vagueness to greater and greater clarity, precision, and detail. Such a circumstance begs of a concept that explains this progression instead of artificially demarcating signs from non-signs.

In relying on the Saussurean semiotic for his attempt to discern the semiotic systematization of language, Hjelmslev—like most linguists—overlooks the far subtler and more compelling semiotic of Charles Sanders Peirce, which originated prior to the work of Saussure, though it seems likely that the latter was unaware of Peirce’s seminal work. Peirce discerned in the sign three interrelated elements (in contrast to Saussure’s simple dyad of signifier and signified): the Sign itself, the sign’s Object, and the Interpretant, a cognitive response to the sign that is itself a sign. Further, Peirce devised several well-known taxonomies of signs, of which the best-known is the triad Icon, Index, and Symbol. Icons are signs that impart meaning based on some sort of shared characteristic or quality, or in other words, by bearing some similarity to their object—a photograph, for example. Indexes impart meaning by directing the mind forcibly (usually, although not necessarily, physically) to their objects, in the manner of a pointing finger or a deictic expression like “that”. Symbols depend for their meaning entirely upon convention. Most, although not all words, are primarily symbolic, inasmuch as their relationships with their meanings are purely conventional. Symbols are thus the “purest” class of sign, since their entire raison d’être is in being interpreted as such. Moreover, these three types of signs operate together; all Indexes involve an Icon, and all Symbols of necessity involve both an Icon and an Index. Besides Icon-Index-Symbol, a classification based on the way in which a Sign relates to its Object, Peirce also devised several other sign typologies, like Qualisign-Sinsign-Legisign, all of them triadic.

3. The Peircean Categories

The triad is of central importance to Peirce’s architectonic or all-encompassing philosophy, because he regarded the entire universe of being as fundamentally triadic. This primordial Triad is defined in terms of three absolutely fundamental ontological Categories, which Peirce aptly (if a little prosaically) styled Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness.

It is inadequate to insist that these ontological Categories merely permeate the physical and cognitive universe; in actuality, they are the very essence of Being, whereof the universe, with all of its properties and constituents, are emergent properties. In other words, every observable object, phenomenon, or event may be characterized in terms of one or more of these Categories, such that certain things tend to approximate pure Firstness, others pure Secondness, and so forth. Compound and complex phenomena typically manifest or embody more than one of the Categories.

In the broadest possible characterization, a First or Firstness is “the Idea of that which is such as it is regardless of anything else” (CP 5.66). In more familiar terms, this ontological Category predominates in such phenomena as quality, emotion, feeling, and the present or presentness. Second(ness) refers to any reactive phenomenon, or in Peirce’s characterization, “the Idea of that which is such as it is as being Second to some First, regardless of anything else, and in particular regardless of any Law, although it may conform to a law” (ibid.). Secondness predominates in such phenomena as resistance, opposition, effort, and pastness, and is the dominant feature in the material domain. Third(ness) refers to phenomena involved in the process of representation, writ large, i.e., “the Idea of that which is such as it is as being a Third, or Medium, between a Second and its First” (ibid.). Thirdness predominates in such notions as thought, habit, intention, law, and futurity. From a semiotic perspective, an Icon may be said to be a sign whose mode of representation is a First, an Index a sign that relies on a Second to signify, and a Symbol a sign whose representational power is a Third.

In addition to the three pure Categories, Peirce also deduced that there are three fundamental “degenerate” Categories that arise from the relative modes of being of Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. Thus Firstness, being absolutely primordial, admits of no degenerate or lesser state, but of Secondness there is a less pristine version, a mere Quality of Secondness, as it were, that Peirce called a Firstness of Secondness. Thirdness admits of two degenerate varieties, qualitative Thirdness or Firstness of Thirdness and reactive Thirdness or Secondness of Thirdness. It is important to note that these inter-Categorial relationships are not commutative; there is no Thirdness of Secondness or Secondness of Firstness, e.g.

Like the “pure” Categories, the three “degenerate” Categories also encompass certain types of objects and phenomena, but because Peirce devoted far less ink to exemplifying and describing them than to the “pure” Categories, in-depth characterizations of these degenerate Categories are somewhat elusive in Peirce’s writings.

For Firstness of Secondness (or [12]), the most thorough description offered by Peirce is as follows:

Category the Second has a Degenerate Form, in which there is a Secondness indeed, but a weak or Secondary Secondness that is not in the pair in its own quantity, but belongs to it only in a certain respect. Moreover, this degeneracy need not be absolute but may be only approximative. Thus a genus characterized by Reaction will by the determination of its essential character split into two species, one a species where the Secondness is strong, the other a species where the Secondness is weak, and the strong species will subdivide into two that will be similarly related, without any corresponding subdivision of the species. For example, Psychological Reaction splits into Willing, where Secondness is strong, and Sensation, where it is weak; and Willing again subdivides into Active Willing and Inhibitive Willing, to which last dichotomy nothing in Sensation corresponds. (CP 5.69)

Elsewhere (CP 1.365), Peirce gives some additional detail about the nature of Firstness of Secondness (or “degenerate Secondness”) with respect to “pure” or “genuine” Secondness:

[T]here is a degenerate sort [of Secondness] which does not exist as such, but is only so conceived. The medieval logicians (following a hint of Aristotle) distinguished between real relations and relations of reason. A real relation subsists in virtue of a fact which would be totally impossible were either of the related objects destroyed; while a relation of reason subsists in virtue of two facts, one only of which would disappear on the annihilation of either of the relates…. Rumford and Franklin resembled each other by virtue of being both Americans; but either would have been just as much an American if the other had never lived. On the other hand, the fact that Cain killed Abel cannot be stated as a mere aggregate of two facts, one concerning Cain and the other concerning Abel. Resemblances are not the only relations of reason, though they have that character in an eminent degree. Contrasts and comparisons are of the same sort. Resemblance is an identity of characters; and this is the same as to say that the mind gathers the resembling ideas together into one conception. Other relations of reason arise from ideas being connected by the mind in other ways; they consist in the relation between two parts of one complex concept, or, as we may say, in the relation of a complex concept to itself, in respect to two of its parts…. But [all these relations] are alike in this, that they arise from the mind setting one part of a notion into relation to another. All degenerate seconds may be conveniently termed internal, in contrast to external seconds, which are constituted by external fact, and are true actions of one thing upon another.

Robertson (1994), in his examination of English verb affixal morphology in light of the Peircean Categories, characterizes Firstness of Secondness as existing “where the mind sees a single notion as two, or where one of the two objects is vague and the other a more focused version of the other”.

In other words, Firstness of Secondness always involves an unequal dichotomy. It is the result of the mind resolving a single idea into two objects, complementary or opposing. We might add that, just as a pure Firstness must be understood to absolutely exclude all Seconds and Thirds (CP 1.358), a Firstness of Secondness will, by its very nature, tend to exclude Thirdness altogether.

As for the two degenerate forms of Thirdness, Secondness of Thirdness (or [23]) and Firstness of Thirdness (or [13]), Peirce characterized them both as forms where “the irreducible idea of Plurality, as distinguished from Duality is present indeed but in maimed conditions” (Peirce, 1998, p. 161). Where Secondness of Thirdness is concerned, Peirce characterized this “Plurality” as “an irrational plurality which, as it exists, in contradistinction from the form of its representation, is a mere complication of duality” (ibid.). Firstness of Thirdness, on the other hand, “is where we conceive a mere Quality of Feeling, or Firstness, to represent itself as Representation” (ibid.). Elsewhere (Bonta, 2015), we have shown that these two degenerate Categories, [13] and [23], may be represented in terms of recursive or cyclical plurality ([13]) and compulsive or repetitive plurality ([23]). As these two sub-Categories are not relevant to what follows, we refrain from further elaboration of them in this study.

Instead, our purpose being to show the manner in which such a fundamental Category, whether pure or degenerate, can be the ordering principle behind an entire semiotic system, we confine our discussion to the degenerate Category Firstness of Secondness, in order to show how this Category serves as the chief systematizing principle for the Chinese language. We have alluded to this circumstance elsewhere (Bonta, 2015, in press), in the larger context of Chinese culture, but in this study, we aim to focus in far greater detail on the ways by which Firstness of Secondness constrains Chinese grammar in all of its aspects.

We restate from the preceding the essential features of this sub-Category for convenience. Firstness of Secondness, as a hybrid Category, is always manifest as a dichotomy. From Peirce’s characterization, this dichotomy always incorporates a stronger and a weaker element, an opposition of unequals, as it were. This opposition of unequals tends to give rise to a catena, whereof the stronger element of a prior opposing pair subdivides anew into another pair of unequal opposites, and so forth. It is also manifest wherever the mind represents a single concept as composed of two unequal, complementary, or opposing elements. Firstness of Secondness is perhaps most nearly embodied by the phenomenon of existence (as a Peircean Immediate Object), which, it will be readily appreciated, may always be characterized by opposites that, in some regard, are unequal. For example, the action of physical forces is characterized for mathematical convenience in terms of opposite and equal vectors in classical dynamics. Thus when a man pushes against a wall, the wall is represented as “pushing back” with an equal and opposite force. But of course, in reality—in the non-abstract world of events—one side or the other will prevail. Ordinarily, the wall will prove immovable to the man’s unaided strength, and he will at length desist and leave the wall as it was. But if he returns with a bulldozer, the tables will be turned. In each case, the opposing forces will be characterized as equal and opposite, but in reality—except under conditions of absolute stasis—an underlying diachronic inequality will ensure the occurrence of some event, in this case, either the collapse of the wall or the surcease of efforts to topple it. This sort of opposition—and not the radical dualism so enthusiastically embraced by those of a Manichaean philosophical bent—is the real “stuff of which dreams (and reality) are made”.

Additionally, as already noted, the sub-Category [12] perforce excludes [3], a condition that will have far-reaching consequences for our study. As a result, any sign or sign system whereof [12] is the immanent ordering principle will seek to reject or minimize all modes of representation that smack of Thirdness—symbolism, eternalism, teleology, synechism, etc.

An underlying assumption of our approach is that explicitness is tantamount to semiotic emphasis. The Peircean sign involves both explicit and non-explicit elements (i.e., visible and audible signs in conjunction with mental ones). This is as true with linguistic signs as with any other. The overt representation of a notion like plurality via morphology is an index of the semiotic prominence afforded this notion in the linguistic semiotic system under consideration. The absence of an overt plural marker does not mean that there is no mental representation whatsoever of plurality; it merely means that no semiotic emphasis is accorded this particular idea. And the reason for such varying emphases from one language to another resides ultimately in the semiotic lens—the conditioning ontological Category used to represent the universeas-Other.

4. Essentials of Mandarin Chinese

4.1 [-3] as a conditioning constraint

Even the casual student of Mandarin Chinese is quickly struck by the peculiar simplicity of both the grammar and word structure, at least in comparison with European languages, with their penchant for polysyllabic words, irregular verbs, and elaborate conjugations and declensions. To cite just one striking example: in Western languages, it is a given that, if an explicit copula is permitted or required, it will take the form of an extremely irregular verb. In English, “be” is the most vexing of all verbs, displaying a total of eight forms (be, am, is, are, was, were, been, being). In Spanish, not one but two different verbs (ser and estar) may serve as the copula—both of them highly irregular, even by the nuanced standards of Spanish verb morphology. Each of these verbs displays more than 50 distinct simple forms, for a total of more than 100. In stark contrast, the explicit copula in Chinese has but one simple form, shì, which suffices for all tenses, moods, numbers, and persons in any Western language. The same can be said for all other verbs and predicates in Chinese vis-à-vis Western languages. Western learners of Chinese are typically astonished to learn of the total absence of tense, number, and person morphology—indeed, of affixal morphology of any kind—in Chinese verbs.

As for nouns, Chinese comes as close as any attested language to having no explicit plural marker. The only place where a plural marker is obligatory in Chinese is among personal pronouns, where the affix -men distinguishes singular from plural in all three persons. Besides personal pronouns, -men may be used to pluralize a limited number of common nouns denoting people, such as háizi-men, ‘children’ (háizi = ‘child’), but in such cases, it is not obligatory and the plural is often expressed without this affix. All other nouns have no explicit morphological differentiation between singular and plural.

Thus, modern Mandarin Chinese is perhaps the closest approximation to a pure analytic language found anywhere on the earth. Nor is this a recent development: classical Chinese from as long ago as the 5th Century BC displayed a similar paucity of inflectional morphology. For the Western student of Chinese, therefore, learning the language often seems more like memorizing and deploying useful idioms than mastering a complex system of inflectional rules to be applied predictably to broad lexical classes like nouns and verbs. The chief difficulty for the Western student of Chinese is becoming familiar with the utterly different sounds and phonotactic rules of a language with no discernible relationship to the languages of Europe.

Elsewhere (Bonta, 2018) we have noted that languages are subject to semiotic classification depending on the strategy that they tend to employ for expressing the relationship between the two fundamental parts of the propositional sign, the subject and the predicate. In effect, that relationship concerns the symbol of assertion that conjoins the predominantly indexical subject with the iconic predicate. Where overt, this symbol of assertion sometimes coincides with the grammarians’ copula, which stands for “an act of consciousness” (Peirce, 1998, p. 20)—the most fundamental aspect of language, and of thought generally. It is important to clarify that by “subject” and “predicate” are not meant the corresponding parts of speech canonized (mostly) by grammarians of Indo-European languages. Instead, “subject” we understand to signify the set of indices—grammatical subjects and objects alike—intrinsic to the predicate, and “predicate” to signify the entire set of ideas involved in the verb or other grammatical predicate. Thus Peirce’s example (Peirce, 1998, pp. 20-21):

[I]n order properly to exhibit the relation between premises and conclusion … it is necessary to recognize that in most cases the subject index is compound, and consists of a set of indices. Thus, in the proposition “A sells B to C for the price D,” A, B, C, D form a set of four indices. The symbol “____ sells ____ to ____ for the price ____” refers to a mental icon, or idea, of the act of sale, and declares that this image represents the set A, B, C, D, considered as attached to that icon, A as seller, C as buyer, B as object sold, and D as price. If we call A, B, C, D four subjects of the proposition and “____ sells ____ to ____ for the price ____” as predicate, we represent the logical relation well enough, but we abandon the Aryan syntax.

As for the symbol of assertion which underpins every proposition, it may be signified by some overt morphology, such as a copula, across language—or it may be non-explicit, a mental sign with no formal linguistic realization. This latter circumstance is most typical of Chinese although, as mentioned previously, the overt copula shì is deployed in some contexts, most notably when the subject complement is a noun.

But part of the symbol of assertion is the colligation of the subject and predicate, the notion that the two are being brought into a relationship whereby the iconicity, or Firstness, of the latter is applied to the indexicality, or Secondness, of the former. This colligation or connection between subject and predicate (as well as degenerate instances of colligation, which we may style attribution) may be represented formally by any of three fundamental morphosyntactic strategies. These strategies—agreement, contiguity, and blending—correspond respectively to the three ontological Categories Thirdness, Secondness, and Firstness. Thirdness, the Category associated with mediation, is manifest in such phenomena as habit and symbolism, as we have already seen. Agreement, mediated by inflection, involves the purely symbolic relationship between word pairs, like subject-verb and modifier-modified, signalized by affixation. Thus, for example, there is no formal similarity between the Spanish verb affix -mos, which marks the first person plural, and nosotros/nosotras, the pronoun to which it refers, or between -s, which marks the second person informal singular, and tú, the second person informal singular pronoun, but the agreement relationship serves to connect these two elements notwithstanding. The fact that agreement is the strategy corresponding to idea association qua Thirdness is peculiarly significant for Chinese inasmuch as, as we have already posited, the preponderant Category-sign underlying the Chinese linguistic sign system is Firstness of Secondness; [12] is a domain in which (as with pure Firstness; see CP 1.357) we would expect the involvement of Thirdness to be diminished as far as possible. Chinese has no morphological agreement of any kind, and precious little inflectional material besides. As a predominantly analytic language, its primary mode of idea association is contiguity, albeit (as we shall see) of a rather idiosyncratic type, and contiguity is a manifestation of Secondness.

Thus the most general conditioning feature of Chinese morphosyntax is the nearabsolute exclusion of Thirdness as a mode of significative structure; we may denote this condition as [-3].

Yet if it is broadly true that Chinese is conditioned by a pervasive absence of Thirdness/[-3], then that trait ought to be manifest systemically, and not only at the level of morphosyntax. In the lexical context, too, we might expect Chinese to seek to minimize the symbolic element as far as possible. Regarding lexical items, or words, as signs, we consider the three different ways by which a sign may represent its object, viz., as an Icon, an Index, or Symbol. As noted already, Icons derive their significative force by virtue of some qualitative resemblance, or iconicity (Firstness), Indexes by virtue of some physical or mental deixis (Secondness), and Symbols by virtue of a mental habit or law of association (Thirdness). In general, words qua Symbols figure most prominently in human language, with iconic entries like onomatopoeia and indexical terms like demonstratives constituting more specialized classes.

The most striking fact about Chinese lexemes is that all irreducible lexemic elements are monosyllabic; there are no irreducible disyllables in Chinese. Not only that, Chinese allowable syllable types are strikingly limited, compared to English. Chinese has only a total of about 400 possible syllables (a number that increases to about 1300 if tones are taken into account), as compared with at least 10,000, and possibly as many as 15,000, for English, depending on the dialect. As a result, Chinese has an extraordinary number of homophones, including strict homophones as well as near-homophones differentiable only by tone. All disyllabic or polysyllabic words in Chinese are strings of monosyllabic lexemes, nearly all of which may have full word value in certain contexts. This is in striking contrast with English and other Western languages, as well as many Asian language families (such as Dravidian), which both feature polysyllabic unanalyzable roots and which frequently borrow polysyllabic, unanalyzable words from other languages. All such words are symbolic, as far as English speakers are concerned; thus, a word like “centipede” may be derived from Latin roots recognizable to the linguist, but for most English speakers, it is simply the analyzable word-symbol denoting a type of many-legged terrestrial arthropod. The situation is far different in Chinese, where the word for ‘centipede’, wúgōng, is a typical disyllabic Chinese word consisting of two monosyllabic lexemes, each of which has full word value—in this case, wú (‘centipede’) and gōng (large Scolopendra-type centipede). Or consider ‘galaxy’, an unanalyzable three-syllable English word derived ultimately from the Greek for ‘milk’, a fact irrelevant to modern English speakers, who regard the term as a more or less arbitrary symbol for a large star system. However, the Chinese equivalent, xīngxì, is, once again, decomposable into monosyllabic lexemes, in this case, xīng, ‘star’, and xì, ‘system’. Besides English, other Indo-European languages and many other language families besides have many such unanalyzable non-borrowed polysyllabic roots. Thus, in English, heaven, German, Himmel, Spanish cielo, and Russian nebo, an unanalyzable disyllable denotes the location where divine beings dwell; but in Chinese, the equivalent tiān-táng means literally “sky dwelling”. In other words, Chinese has reduced the number of allowable arbitrary sound symbols to an absolute minimum number, and ensured that they are all monosyllabic and minimally variable. Nearly all multisyllabic Chinese words are decomposable into monosyllabic lexemes, and never constitute arbitrary polysyllabic Symbols in and of themselves. Put otherwise, only the simplest meaning elements are conveyed by a very limited allowable set of purely symbolic monosyllabic lexemes, and all more complex polysyllabic “words” (so styled) are composed entirely of such simple monosyllables. All such polysyllabic words are therefore highly indexical, inasmuch as they inevitably direct the mind to the set of monosyllabic lexemes from which they are derived. In other words, the Chinese lexicon, too, has undertaken to reduce as far as possible the symbolic dimension, or Thirdness, as a result of the constraining influence of Firstness of Secondness.

In the domain of writing, it is well known that Chinese writing is logographic. It is a significant fact that, in spite of considerable social debate spanning many decades, modern China persists in maintaining a cumbersome and exceedingly complex writing system in use for millenia. Nearly impossible to adapt to the requirements of modern civilization, Chinese writing is nowadays as prevalent as ever, being the medium of choice (in contrast to pinyin or Romanized Chinese writing) online. So attached are the Chinese to their writing that—given the impracticality of creating a usable keypad with Chinese characters—their computers and cell phones generate characters in response to pinyin or even handwritten input, a remarkable tolerance of inefficiency among such a famously practical people.

It has been argued that Chinese, because of its high degree of homonymy, could not possibly be intelligible without the characters. Instead of converting to an alphabetic system, the mainland Chinese have adopted a somewhat simplified version of the characters—yet the principles of writing remain the same, and Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan continue to use the traditional inventory of characters. Moreover, at least one Asian country—Vietnam—whose language is very similar to Chinese overall, opted, under French influence in the early 20th Century, to abandon the Chinese writing system (along with the related Chu Nom Vietnamese characters) and replace it with a modified Romanized alphabet.

It has also been asserted, with somewhat more plausibility, that Chinese writing helps to bridge the gap among mutually unintelligible Chinese “dialects”, most notably Cantonese and Mandarin (the only two with official status), although the same could be said of Hokkienese, Hakka, Wu, and other major dialects in China.

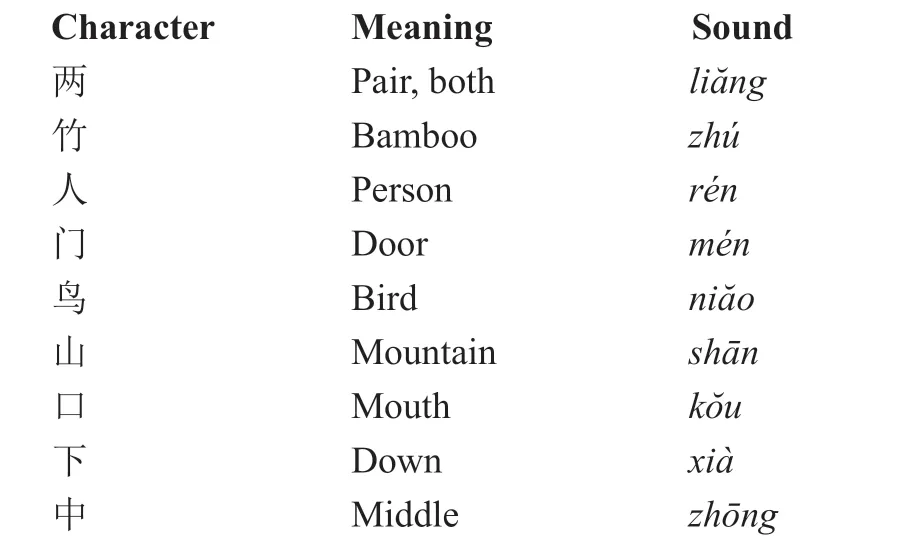

Whatever the case, Chinese writing is the nearest writing system in the world today to pictographic writing—that is, most simple characters are highly iconic, even having acquired a veneer of stylization with the passage of millenia. Characters and radicals denoting people, animals, plants, insects, buildings, places, and even abstract ideas, are very recognizably iconic, to a degree that far surpasses any other living writing system. Thus, for instance, the following common characters (to present a very small sampling) are very transparently iconic with respect to their denotata:

Table 1. Iconicity in Chinese characters

Besides these (and many other) easy to see iconic representations, the Chinese signary contains hundreds of other compound signs made up of constituent simple characters that represent actions, attitudes, or things relevant to the object being represented, such as 明, ‘bright’ (sun [on the left] and moon characters combined), 休, ‘rest’ (composed of the characters 人, ‘person’ and 木, ‘tree’), and 好, ‘good’ (composed of 女, ‘woman’ and 子, ‘child’).

A large majority of all Chinese signs (80 percent or more) are so-called pictophonetic (or semantic-phonetic) compounds, consisting of a semantic indicator (or radical) denoting the general meaning of the compound, and usually a stylized or simplified version of another sign, and the phonetic indicator, which represents the sound of a similar-sounding character. For example, the character 沖, ‘surge’ (chōng), is composed of a water radical (the three short strokes on the left, a reduced form of the water character 水) and the above-illustrated character 中, ‘middle’ (zhōng), which sounds quite similar. Signs such as these are strongly indexical (rather than symbolic or even, for the most part, iconic in such compounds), that is, they explicitly direct the reader to look at other, simpler signs (which are in the main iconic) to deduce their meaning and sound value.

In other words, the overwhelming majority of Chinese characters are either strongly iconic, strongly indexical, or both—but almost never symbolic, after the manner of alphabets, abjads, syllabaries, abugidas, and other primarily phonetic and phonological writing systems. Put otherwise, the Chinese writing system is overwhelmingly reliant on Firstness and Secondness in signifying; Thirdness is extremely muted.

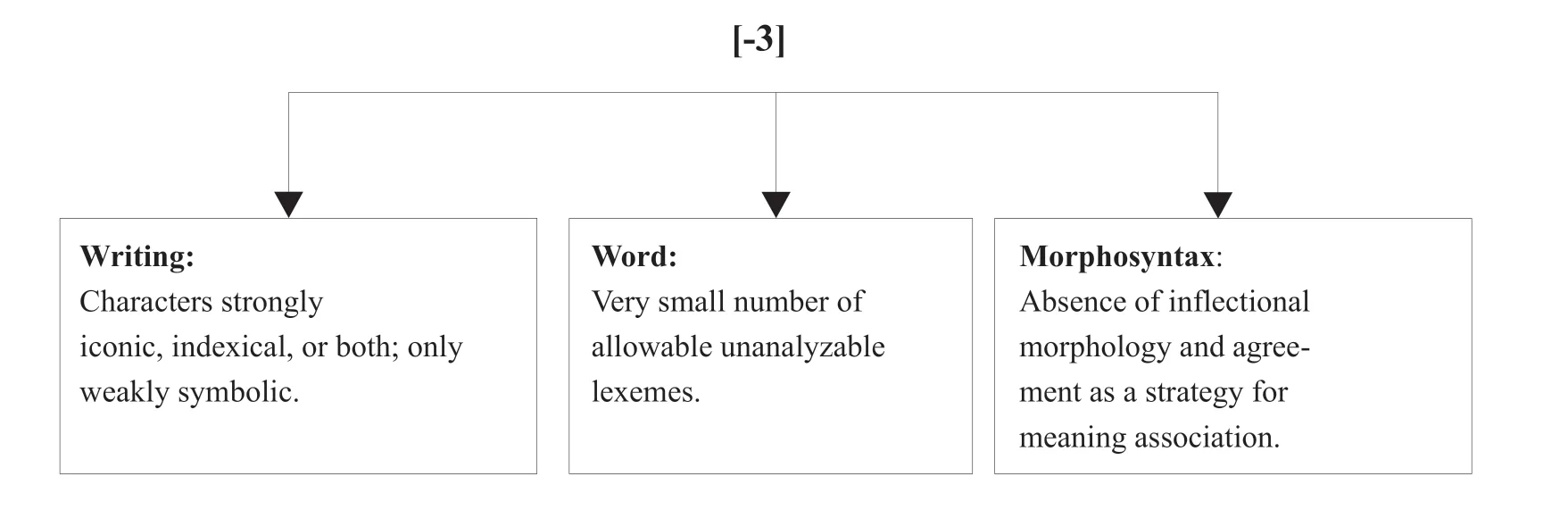

With the foregoing characteristics of the Chinese lexicon, morphosyntax, and writing, we note our first concrete evidence of several apparently disparate elements of language conjoined as a systemic semiotic whole. A uniform tendency to minimize Thirdness, [-3], has led to the near-nullification of inflectional morphology that could mediate agreement, to the almost absurd simplicity of the Chinese lexicon, with its paucity of allowable syllables and its absolute insistence on the monosyllable as the sole unanalyzable meaning-element, and even to the persistence and luxuriance of a complex writing system reliant almost completely on iconic and indexical representation. These signal characteristics of Chinese language may be summarized graphically as follows:

Table 2. [-3] as a general conditioning constraint

4.2 [12] as a conditioning constraint

We anticipate that the systemic semiotic constraint of Firstness of Secondness will impose two unifying structural characteristics on the Chinese language in all of its aspects. The first of these, the reduction, as far as possible, of Thirdness/Symbolism/[-3], we have already examined. This is a negative semiotic constraint, and it is the more significant for the fact that, whereas Thirdness will always involve both Secondness and Firstness (i.e., a symbol will always involve an index and an icon) and Secondness will always involve Firstness (an index will always involve an icon), these implicational characteristics (as already noted) are not commutative; neither a Firstness nor a Secondness will necessarily involve a Thirdness.

We now turn our attention to the second expected semiotic constraint, the positive requirement that semiotic structures in all aspects of the Chinese language will tend to configure themselves after the nature of Firstness of Secondness/[12]. Recalling that Firstness of Secondness always involves an unequal dichotomy with a stronger/more prominent and weaker/less prominent element, we may consider whether this semiotic and structural pattern is manifest in Chinese, and to what extent.

Examining phonology first of all, we note that Chinese, unlike Western languages, employs two very different kinds of distinctive features to differentiate meaning. Like all languages, Chinese employs a set of oppositional distinctive features that differentiate phonemes; we hasten to clarify that distinctive features qua signs are best represented in terms of the oppositional acoustic features as set forth, e.g., by Jakobson and Waugh (1979). It is the oppositional character of these features that confers on them significative force, where the signatum (i.e., the Peircean Object) is primarily understood to be mere “otherness”:

The sole signatum of any distinctive feature in its primary, purely sense-discriminative role, is ‘otherness’: as a rule a change in one feature confronts us either with a word of another meaning or with a nonsensical group of sounds…. Distinctive oppositions have no positive content on the level of the signatum and announce only the nearly certain unlikeness of morphemes and words which differ in the distinctive features used. The opposition here lies not in the signatum but in the signans: phonic elements appear to be polarized in order to be used for semantic purposes. Such a polarization is inseparably bound to the semiotic role of distinctive features. (Jakobson & Waugh, 1979, p. 47)

Such distinctive featural acoustic oppositions, likely to be unfamiliar to students of articulatory phonetics and phonology, include grave/acute, compact/diffuse, and strident/mellow (which may have differing articulatory realizations across languages). This oppositional character, be it noted, is confined to distinctive features, and appears to be absent from, or at least less conspicuous among, other sorts of features, such as redundant, prosodic, and emotive (ibid.).

The oppositional character of the network of distinctive features gives rise to an array of phonemes differentiated in terms of featural contrasts, extending the notion of meaning as “mere otherness” to the phonemes themselves. Thus phonemes, and the distinctive features of which they are composed, derive their semiotic force almost entirely from the oppositional “mere otherness” of featural contrasts.

With Chinese and other “tonal languages”, however, we see manifested a novel type of feature, which, whether from an articulatory or acoustic posture, cannot be represented as oppositional: the sense-discriminative tones themselves. Mandarin Chinese is comparatively impoverished tonally in possessing only four tones (or perhaps five, if the “l(fā)ight” or null tone is taken into account). Each of these tones participates critically in the sense-discriminative task alongside other distinctive features and the phonemes they constitute, but, in stark contrast to the “otherness” of oppositional distinctive features and the phonemes they constitute, the signatum of tones may be characterized as “suchness”. The maximal canonical syllable in Chinese may be expressed as CGVXT, with C an initial consonant, superscript T the tone, and GVX the syllable-final configuration consisting of a medial glide G, a vowel V, and a coda X made up of a very limited set of permissible phonemes. While certain elements of this configuration may be absent (the initial consonant, for example), the tone is obligatory. The tone is a feature pertaining to an entire lexeme-syllable, although it is realized as part of the vocalic, and not consonantal, configuration. It is crucial in establishing the semantic identity of a lexeme in a system where, as already mentioned, homophony is pervasive.

Chinese in the featural domain therefore presents a pervasive dichotomy: sense discrimination is produced by a pairing of othernesses (the set of phonemes and distinctive features) with suchness (the tonal features). That the stronger or more prominent element of this pairing is otherness/distinctive features is evidenced by an array of circumstances. In any given minimal lexeme, an ensemble of distinctive features and phonemes will be present, in contrast with but a single tone. A lexeme can still be intelligible with its tonality suppressed, as evidenced not only by the diminution of tone value in the final syllable of many di- or polysyllabic words, but also in music, where sense-discriminative tones are overwhelmed by the melody; but a lexeme with distinctive features suppressed would be nonsensical. And Chinese rebuses and puns, whether in humor, taboo language, or the formation of soundsuggestive radicals within Chinese characters, all rely for their force on phonemic similarity, and not on tonal correspondence. Indeed, formal similarity is reckoned only in terms of distinctive features, not tones, as evidenced, for example, by the wellknown taboo against the number ‘four’ (sì) for its similarity to the word for ‘death’ (s?). Finally, distinctive features operate at a more fundamental level (the phonemic, to discriminate sounds) than tones, which operate at the lexemic level, to discriminate meaning.

In the stronger, more prominent element in this dichotomy, the distinctive features, Secondness is more prominent, inasmuch as the indexical force of distinctive features resides in their oppositional character—opposition being a cardinal attribute of Secondness. In the weaker, less prominent element, the tonal features, indexicality or Secondness is still present, but it is tempered by the intrinsic character of the tones, they being indicative of suchness, a qualitative mode of being characteristic of Firstness. Taken as a whole, the ensemble of distinctive and tonal features together represents a partitioning of entire set of sense-discriminative features into an unequal dichotomy of sets performing complementary tasks. The structure of Chinese at the very most elemental level—the sense discriminative featural register—is thus a perfect model of Firstness of Secondness.

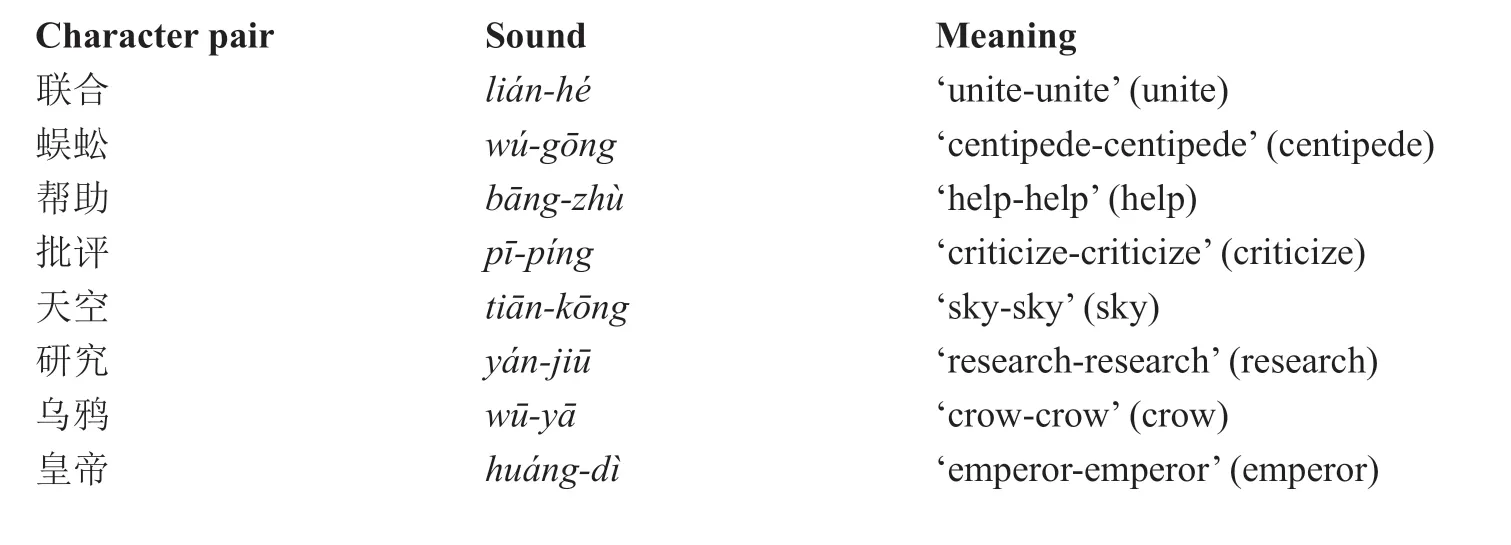

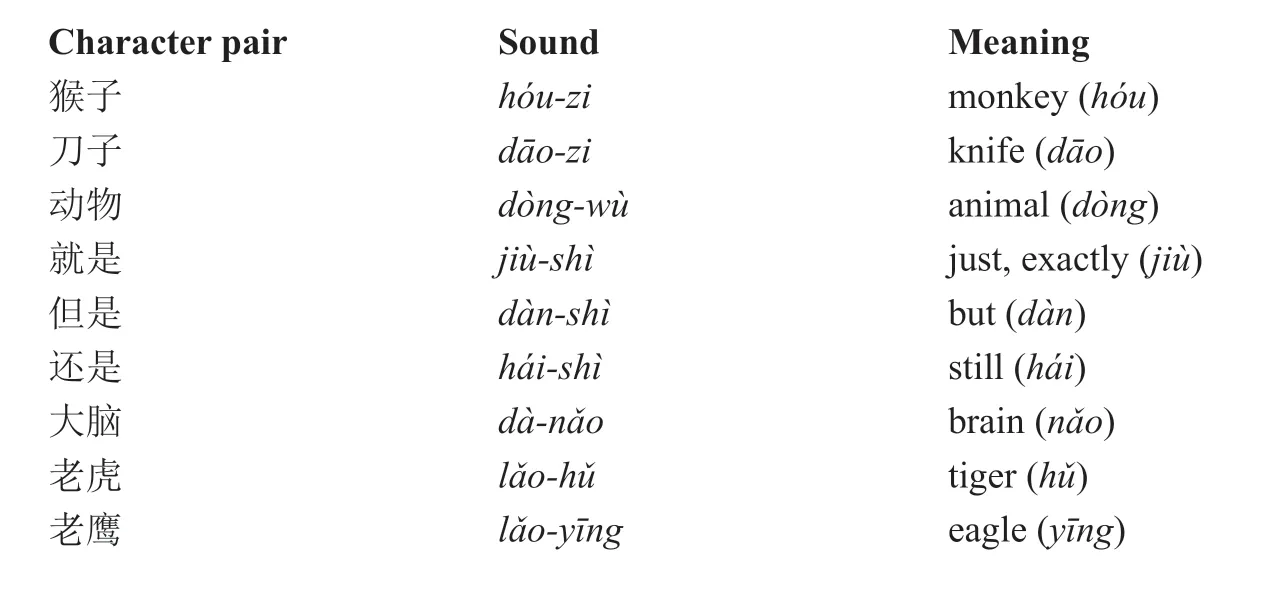

At the lexemic level, the most striking typological characteristic of Chinese is its love for disyllabic, dilexemic words. The overwhelming majority of Chinese words are disyllabic, even though every Chinese monosyllable also has full word value. These disyllables follow various compositional patterns, including figurative oppositions (e.g., dōng-xī, ‘thing’, literally, ‘east-west’) and phrasal verbs incorporating an object (e.g., zuò-fàn, ‘cook, prepare food’, literally, ‘make-food’). Two especially interesting and common patterns involve the addition of a gratuitous syllable with essentially no meaning, like -zi, -shì, -wù, lǎo-, and dà- purely to create a disyllable, and the redundant pairing of two lexemes that both have the same meaning.

For the former category, the “empty” lexemes all have, or once had, full word value, viz., -zi, ‘child, offspring’, -shì, ‘be, is, are’, -wù, ‘object, thing’, lǎo-, ‘old; venerable’, and dà-, ‘big’. But in such disyllabic compounds, they have been grammaticalized for the purpose of prosodic augmentation. Thus, e.g., the disyllable dàn-shì does not mean ‘but is’, or some such, but rather is synonymous with (and, in the spoken language at least, much more frequently deployed than) the monosyllable dàn, ‘but’. In like fashion, lǎo-yīng does not mean ‘old eagle’, but simply ‘eagle’.

For redundant pairings, the individual entries in such pairs are not always exact synonyms, and some of them can be used individually as well. For example, bāng and zhù in bāng-zhù can both occur individually as well as in other disyllabic compounds, such as xié-zhù, fǔ-zhù, and bāng-máng, all of which mean ‘help’.

On Tables 3 and 4 following we illustrate a few examples for each of these two common patterns:

Table 3. Redundant pairings

Table 4. Pairings with “filler” syllables -zi, -wù, -shì, dà-, l?o-

From these two sets of examples in particular, we see that the Chinese need of disyllables and dilexemes is both pervasive and compulsive. In pairings of the two types shown on the above tables, we can also see that such pairings are asymmetric, with one member being the dominant or prior element. In pairs with “filler” syllables, like disyllables with -zi, this asymmetry is glaringly apparent; most of the meaning is carried by the first syllable, which may also occur alone with full lexical meaning (especially, although by no means exclusively, in literary contexts).

With redundant and other kinds of pairings, the strong element may often be discerned by which of the two lexeme-syllables is chosen in the creation of new compounds (which are typically themselves reduced to two syllables). For example, the term for a “security check (point)”, ān-jiǎn, is a compound of ān-quán, ‘security’ (literally, ‘calm-all’) and jiǎn-chá, ‘check’ (literally, ‘check-check’); in this instance, it is the initial syllable of each of the two contributing disyllables that is enlisted to form the new word, suggesting that those two syllables are the “strong” members of their respective dichotomies. One more example of thousands that we could cite should serve to reinforce the point. A word familiar to most foreign residents of China’s large urban centers is dì-tiě, ‘subway, metro’, which is in fact a compressed form of dì-xià tiě-lù, ‘earth-under iron-road’ (i.e., ‘underground railroad’). While it is not universally the case that the initial syllables in such disyllables are selected for use in compounds, it appears to be the case more often than not. A more exhaustive treatment of this fascinating subtopic, the criteria for establishing the dominant or prior member of a dilexemic word, is beyond the scope of this paper, but it should suffice to say that certain lexemes are consistently chosen, and therefore appear to be intrinsically regarded as “strong”. One such syllable is dì-, which is a very frequent initial entry in dilexemic words, including dì-qiú, ‘world’ (literally, ‘earth-ball’), dì-tú, ‘map’ (literally, ‘earth-diagram’), and dì-dào, ‘tunnel’ (literally, ‘earth-way’).

This pattern of selecting a single lexeme-syllable to represent a dilexemic word in reduced form in a compound is found with all kinds of dilexemic words.

These two traits—a pervasive love of disyllabic, dilexemic pairs in word formation and the reduction of such pairs to a single lexeme-syllable to represent the word in compound formation—are the two defining characteristics of the Chinese lexicon. It is evident that the structuring of the Chinese lexicon uses Firstness of Secondness as its patterning principle, whereby a Secondness (in this case, a word, in its indexical character) is manifest as a lexemic dichotomy consisting of a stronger and a weaker element.

We have seen that the positive [12] systemic constraint associated with Firstness of Secondness is strongly and pervasively manifest at both the phonemic and lexemic levels in Chinese. We would do well to inquire whether the constraint [12] is similarly manifest at the morphosyntactic level, to complement the negative [-3] constraint already uncovered there.

The most pervasively distinctive trait of Chinese morphosyntax, aside from the aforementioned near-absence of affixation, is its love of splitting the predicate into either contrastive or complementary elements, an effect achieved in a number of ways, to be detailed below. Most immediately familiar to the beginning Chinese student is the preference for contrastively-structured yes-no questions involving a repetition of the verb, with the second instance negated by either of two negative Chinese prefixes, bú- or měi-, e.g., yào-bú-yào, ‘do you, they/does he, she want?’ (literally, ‘want-nowant’), shì-bú-shì, ‘Right? Isn’t that so?’ (literally, ‘be-no-be’), or y?u-měi-y?u, ‘Is/are there, Do you, they/Does he, she have?’ (literally, ‘There is-no-there is’). These can occur as stand-alone questions, as tag questions (especially shì-bú-shì), or within a larger utterance giving it a yes-no interrogative sense. For example:

nǐhěnxǐhuanzhōngguó,shì-bú-shì?

you very like China be-not-be ‘You really like China, right?’

tāyào-bú-yào

he want-not-want ‘Does he want [it/them/to, etc.]?’

tāmeny?u-měi-y?uqián

they have-not-have money ‘Do they have money?’

In such usages, which are extremely common, Chinese characteristically splits the predicate into two contrastive halves, one strong (negative) and the other weak (affirmative)—the very embodiment of the now-familiar dichotomy type signalized by Firstness of Secondness. The notions of affirmative and negative also embody Firstness and Secondness, respectively (CP 1.359, e.g.), such that these affirmativenegative predicate splits correspond precisely to the explicit resolution of an interrogative into a Firstness/affirmative and Secondness/negative. Note that such interrogative notions can also be expressed by a single, irreducible element, an interrogative postclitic like ma or a. The above question

tāyào-bú-yào

may also be represented as

tāyàoma

he want INTERROGATIVE ‘‘Does he want [it/them/to, etc.]?’with no change in sense whatsoever.

For experiential yes-no questions, Chinese has other ways of achieving the affirmative/negative dichotomy in yes-no questions, most notably (in the north), by using méiyou, ‘not-have’ in conjunction with the experiential affix -gu o, as in

nǐqù-guoshàngh?iméiyou

you go-EXPERIENTIAL Shanghai not-have “Have you gone to Shanghai?”

In southern dialects, the foregoing would more likely be rendered by using the dichotomy yóu méiyou, as in

nǐyóuméiyouqù-guoshàngh?i

you have not-have go-EXPERIENTIAL Shanghai

Thus Chinese morphosyntax allows the extremely common (even preferred) option of splitting the predicate of a yes-no question into contrasting affirmative and negative forms, instead of simply deploying a single verb with an interrogative postclitic. Whether the interlocutor does so is a matter of stylistic choice; when he opts to do so, it is clearly an operative instance of [12], whereby the mind resolves a single concept into unequal parts, per Peirce and Robertson.

But such “predicate splitting” is not confined to yes-no questions. It is also found in affirmative propositions, in various manifestations. The most widespread is a tendency to create a double or compound predicate by affixing to the main verb a secondary verb or stative verb of more general meaning, to refine or amplify the sense of the main verb (so-called “resultative compound verbs”). It should be noted that this is not the same process as the creation of periphrastic tenses and modalities with the use of auxiliary verbs; this process is also found in Chinese, and is morphosyntactically distinct. For example, to say something like ‘I can fix [it]’ in Chinese, we may use a periphrastic construction syntactically quite similar to those found in English:

w?huìxiū

I can fix

or

w?kěyǐxiū

I can fix

But we may also use a resultative compound construction, in which one verb is affixed to another, with the modifying particle -de- separating them (or -bu-, if the sentence is negative):

w?xiū-de-li?o

I fix-POSSESSIVE-be able

Besides -li?o, other such secondary verbs in Chinese include -lái, -jiàn, and -dào, among many others, some of which do not involve the use of the interposed -de-, but are simply affixed directly to the verb (but -bu- is always interposed for the negative).2It is important to note 1) that this process is extremely productive, with a large number of verbs (including, in some cases, verbs that are dilexemic in their own right, such as -qǐ-lái and -míng-bái) available as the second element in such predicate pairings and 2) these pairings are not analyzable as auxiliary/modal + main verb periphrasis. Instead, they involve a splitting of the predicate into two separate ideas, one of which is represented as the stronger member, and the other as the weaker, or ancillary member. As to which is which, the morphosyntactic evidence is unambiguous: whereas the first or leading entry in such combinations is never modified in any way, and always consists of a single lexeme, like tīng or chī, the second entry is usually preceded by -de- if affirmative, and always by -bu- if negative, analogous in the latter respect to the negative entry in yes-no question constructions noted previously. Moreover, the second entry, unlike the first, may consist of more than one lexeme (as with -míngbai and -qǐlai), and may even have an adverb like tài, ‘too [much]’ modifying it. Finally, it is the second element that receives phonotactic stress. Following are some more examples of such resultative compound pairings, with the lexeme bearing the primary meaning in boldface:

tīng-de-d?ng

hear-POSSESSIVE-understand, ‘hear and understand’ (often used instead of ‘understand’ when comprehension of a spoken utterance is referenced)

tīng-bu-míngbai

hear-NEGATIVE-understand, ‘don’t [hear and] understand’

shuō-bu-tài-dìng

say-NEGATIVE-too-be definite, ‘cannot say too definitely/for sure’

kàn-bu-jiàn

see-NEGATIVE-catch sight of, ‘cannot see (i.e., I cannot catch sight of)’

chī-bu-xià

eat-NEGATIVE-go down, ‘cannot get down any more (food)’

Note that second verb entries are sometimes themselves compound lexemes, as with -míng-bai, ‘understand [clearly]’ (míng, ‘clear, bright’, and bái, ‘make clear’). Note also that adverbs like tài, ‘too [much]’, may be inserted before the second entry, as seen in the third example above.

It should be plain that Chinese resultative compounds conform precisely to the pattern embodied by [12] as set forth by Peirce and clarified by Robertson: they involve the conceptual resolution of a single concept into two unequal parts, as with, e.g., tīng-de-d?ng, in which “understanding” is resolved into “hearing” (weak) and “understanding” (strong) or kàn-bu-jiàn, where “seeing” is resolved into “seeing” (weak) and “catching sight of” (strong). Unlike dilexemic, disyllabic words, these compounds do not constitute lexemic entries per se; rather, the formation of resultative compounds is a productive morphosyntactic process with many thousands of potential configurations. Note that, with dilexemic words that are actual lexical entries, the negative particle will always be prefixed instead of inserted between the two lexemes; thus, e.g., bu-míngbái, ‘do not understand’, and not *míng-bu-bái.

Besides such verbal uses, the Chinese predilection for predicate splitting is also evident with adjectival predicates, that is, adjectives deployed with full predicational force (i.e., without an explicit copula) as subject complements. Such verbs include simple monosyllabic lexemes like h?o, ‘[be] good/well’, lèi, ‘[be] tired’, and gāo, ‘[be] tall/high’, as well as disyllabic words like cōngmín g, ‘[be] intelligent’. A singular fact about Chinese usage that soon impresses itself on beginner students is that, although these words (and many others like them) are adjectival predicates, one simply cannot say, e.g., *w?lèi (‘I am tired’) or *tācōngmíng (‘he is intelligent’), despite the fact that the corresponding negatives w?bulèi (‘I am not tired’) and tābucōngmíng (‘he is not intelligent’) are perfectly admissible. But for affirmative uses of such adjectival predicates, some kind of modifier, like h?n, ‘very’, fēicháng, ‘really’, or chāojí, ‘super’, is obligatory, even if no exceptional grade of the quality is being represented. Thus to say, e.g., ‘I am tired’ in Chinese, one must say something like

w?h?nlèi

I very tired ‘I am [very] tired’where h?n is the most common, but by no means the only option; the abovementioned fēicháng and chāojí, among other adverbs of degree, are also admissible.

Similarly, ‘he is intelligent’ must be rendered with some modifying adverb as, e.g.,

tāh?n/fēicháng/chāojícōngmíng

he very/really/super intelligent ‘He is [very/really/super] intelligent’

It should be apparent that this obligatory splitting of adjectival predicate into adjective (strong) and adverb (weak) is yet another pervasive instance of [12] constraining Chinese morphosyntax, whereby a single notion expressed by a predicate adjective is resolved into an adverb + adjective.

Further evidence that this is the case is furnished by the fact that such predicate adjectives can be deployed as affirmatives without an accompanying adverb like h?n or fēicháng—but only when some kind of aspectual modifier is present, such as the completive/contrastive particle -le. Thus if I say instead

w?lèi-le

I tired-COMPLETIVE ‘I am [just now]/have become tired’no preceding adverb like h?n is necessary, although w?h?nlèi-le, ‘I am very tired’, is also admissible.

From all of the foregoing, it should be apparent that the entire structure of Chinese grammar, from the level of sound up through the level of morphosyntax, is conditioned by [12], a fact which may be represented by a branch structure whereof the boldface branch represents the strong component of each dichotomy. We may thusly construct a dichotomy tree that conforms precisely to Peirce’s characterization of Firstness of Secondness subdividing into two unequal elements, whereof the stronger element derived from that operation in turn subdivides again, and so forth. Recall that, per Peirce:

[A] genus characterized by Reaction will by the determination of its essential character split into two species, one a species where the Secondness is strong, the other a species where the Secondness is weak, and the strong species will subdivide into two that will be similarly related, without any corresponding subdivision of the species. (CP 5.69)

In our admittedly preliminary and cursory treatment of Chinese, we may construct a [12]-configured dichotomy tree for

tīng-bu-míngbai

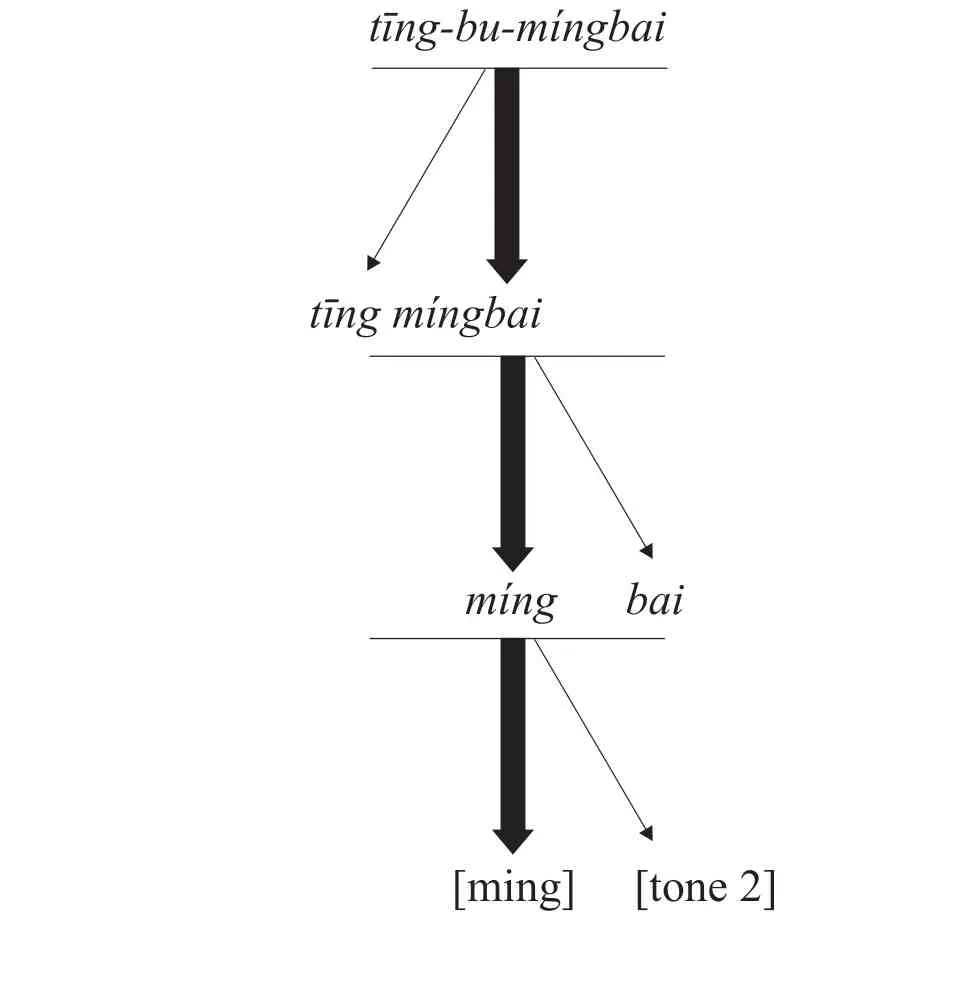

as follows (where boldface arrows indicate strong components):

Table 5. Dichotomy Tree: tīng-bu-míngbai

The dichotomy created by the resultative compound is resolved into a weak element (tīng) and a strong element (míngbai). The latter in turn may be resolved into two lexemic elements, one weak (bai) and the other strong (míng), and the strong lexeme míng is constructed with two separate types of sounds, phonemes (strong), which are themselves composed of strong or contrastive distinctive features, and the tone (weak). This particular dichotomy tree represents three levels of semiosis, though there are certainly more left unanalyzed (prosodic features, for example). It shows, moreover, that not only are the separate levels of grammatical representation in Chinese configured according to the constraints of [12], so too is the entire edifice of the grammar, as to the relationship between one level and the next (as, for example, between syntax and lexeme, or lexeme and phonology). In this way, and only in this way, can the notion of language as a “system of signs” be properly and fully cognized, as a set of linguistic norms assembled on the scaffolding of one (or more) of the primordial ontological Categories, either a “pure” or a “degenerate” Category.

This Categorial scaffolding is comparatively easy to discern in the case of Chinese, a language that, for various cultural and historical reasons, has proven opaque to foreign influences and imports. For this reason, Chinese is a very useful subject to test the theory of Category-signs as the primary sources of semiotic structures and systems undergirding grammar. The comparative utility of this approach is that, unlike syntactic or phonological structures, e.g., semiotic structures are not only generative, they are also concatenated across levels of grammar, from primordial distinctive features to complex morphosyntax and texts. The dichotomy trees that represent the operativity of [12] display the synchronic unity of semiotic structure, whereby complex semiotic arrays (morphosyntax, e.g.) are constrained by a semiotic template held in common with simpler arrays (distinctive features). Not only that, the permanence of a Category-sign as the ultimate constraint on grammar has diachronic implications as well, to wit, we would expect a language constrained by, e.g, [12], to only change over time in directions which this Category can accommodate. With Chinese historically, this has certainly been true; features like tones and the simple phonological structure have proven remarkably resilient, while the Chinese disposition to traffic in dilexemic disyllables has grown with the passing of centuries. We can predict with some confidence, for example, that Chinese will not develop any system of inflection-based agreement, nor that it will evolve to prefer unanalyzable multisyllabic words, in the manner of English or many other Western languages, anytime soon.

The methodology implied by this preliminary study is, first, examine every aspect of phonemic, lexical, and morphosyntactic structure with an eye to discerning the underlying and common semiotic structure constraining these domains separately and also tying them together into a structurally consistent whole. Once a candidate Category-sign has been identified, look for its operations at each level of grammar. At the same time, look for evidence of the absence, or comparative insignificance, of any Category or Categories excluded by the Category-sign in question. For example, a pure Thirdness would imply the diminution of Firsts and Seconds; in Chinese, as we have seen, a Firstness of Secondess implies an exclusion of Thirds, which proved to be easily discernible.

The dichotomy tree representational type used for [12] will be inadequate for semiotic structures arising from other Categories, each of which begs of its own diagrammatic type. The scope of this paper precludes investigation into what forms other diagrammatic types might have.

Language being extraordinarily complex, evidence for all the Categories, in varying degrees, will certainly be discerned in any language under consideration. All full-fledged signs, for example, must partake of some symbolic element, independent of the proclivities of the cognition responsible for the sign’s production. In Chinese, while Thirds are remarkably muted, they are not absent altogether; otherwise, Chinese would be bereft of its significative character. But a Category manifest as a constraining Category-sign will display consistency and prominence; it will be manifest in the most, if not all, grammatical features that define the typology of the language and give it its distinctive identity, as traits like tones, dilexemic words, and resultative compounds do for Chinese.

Not every case will be so simple. In previous work, we have shown evidence for hybrid culture-signs (in, e.g., Sinhalese culture and language; see Bonta, in press), and suggested the likelihood that many modern cultures (and therefore languages) are in fact the product of such semiotic hybridization. In such instances, the constraining influence of two, or perhaps even more, Category-signs may be found to have equal prominence in a grammar, and their mutual interrelations and influences correspondingly more difficult to discern. For this, only further study and elucidation of the Categories and their modes of representation in language will suffice to bring clarity to a field of potentially daunting complexity. But only through the lens of semiotic structures can the regularities and irregularities of human language be contemplated and understood not merely as a set of exclusionary reductionisms, but as a self-consistent, interconnected whole.

Notes

1 Peirce defines synechism as “the tendency to regard everything as continuous” (Peirce, 1998, p. 1).

2 Resultative compounds insert -de- in the affirmative form between the first and second element when their meaning is potential; if their meaning has an actual sense, as it may with some compounds, the infix -de- is omitted. But they are still distinguishable from lexical compounds by virtue of being able to form a potential in -de-; dilexemic verbs that have no such potential form are not resultative compounds.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年1期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年1期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Minimalist Account of Wh-Movement in Fulfulde

- Memes as Ideological Representations in the 2019 Nigerian Presidential Campaigns: A Multimodal Approach

- The Effect of Para-Social Interaction in Endorsement Advertising: SEM Studies Based on Consumers’ Exposure to Celebrity Symbols

- Salomé: A Tragic Muse to Modern Chinese Drama

- Perception of Myth in Print and Online Media