Association between liver targeted antiviral therapy in colorectal cancer and survival benefits: An appraisal

Qiang Wang, Chao-Ran Yu

Qiang Wang, Chao-Ran Yu, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Department of Oncology, Shanghai Medical College, Shanghai 200025, China

Abstract

Key words: Colorectal cancer; Liver metastasis; Antiviral therapy; Survival; Injury status;Biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most common malignancies in the world,with liver metastasis as one of the major distant metastatic lesions[1]. In China, the incidence and mortality of CRC have been increasing[2]. Commonly, liver metastasis occurs at the advanced course of CRC. Surgical intervention, chemotherapy, and target drugs significantly improve the survival benefits. However, overall outcomes of CRC remain largely unsatisfying due to distant metastasis and drug insensitivity[1,2].The underlying mechanisms may be correlated to molecular features and clinical heterogeneity[3-6].

In general, hepatic therapy is incorporated into the comprehensive therapeutic strategy for CRC when liver metastasis is detected. However, a preventive therapeutic idea of introducing hepatic treatment to the comprehensive treatment in early stage is noteworthy. Of note, in patients with hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma,adjuvant antiviral therapy with adefovir reduced recurrence and improved postoperative prognosis[7]. Recently, the same research group introduced a novel conception of antiviral therapy as “the lower the better and the earlier the better” to the therapeutic effects in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a low hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level (HBV-DNA < 2000 IU/mL)[8,9]. In addition,CRC with HBV or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected or cirrhotic liver rarely develops metastatic lesion[10]. Actually, antiviral treatment is routinely taken as a parallel therapeutic strategy for CRC with hepatitis, but its benefit has not been fully recognized. Moreover, the value of antiviral therapy for general CRC patients is rarely investigated. Thus, this review discusses the potential role of antiviral therapy for the overall survival of CRC patients.

ABSENT LIVER METASTASIS IN CRC WITH HBV/HCV

Previously, Utsunomiyaet al[10]reported that CRC patients with either HBV or HCV infection rarely presented liver metastatic lesion. Meanwhile, another study from Italy also indicated that 3.2% of HBV/HCV infected CRC patients developed liver metastasis compared to 9.4% in non-infected cases with statistical significance[11].Moreover, others thought that HBV vaccine could serve to enhance intrinsic antitumor activity in numerous malignancies, including colon cancer[12]. Reasonably to presume that the pre-activated liver immune environment in CRC patients with HBV/HCV infection could be of clinical significance to eradicate potential tumor cells in the liver. Of note, CRC patients with a cirrhotic liver also displayed similar clinical outcomes[13]. However, both clinical observational studies did not fully demonstrate the direct connections between liver metastasis in CRC and corresponding liver disease status.

POTENTIAL MECHANISTIC CLUES

In fact, there are two mechanistic insights that may hold accountable. First, the immune system pre-activated by liver diseases could be of contribution to the identification and eradication of potential cancer cells in the liver. Second, the medical therapy for liver disease (HBV/HCV infected or cirrhotic liver) prior or parallel to the cancer treatment could be another helper. Interestingly, the medical therapy for HBV/HCV consists of a series of drugs associated with immune system regulation and antiviral function[14,15]. In addition, in HBV patients with liver cirrhosis or HIV infection, interferon associated combinational therapy is included[14]. Reduced tumor progression and favored clinical outcome were noticed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma when receiving antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis[16].

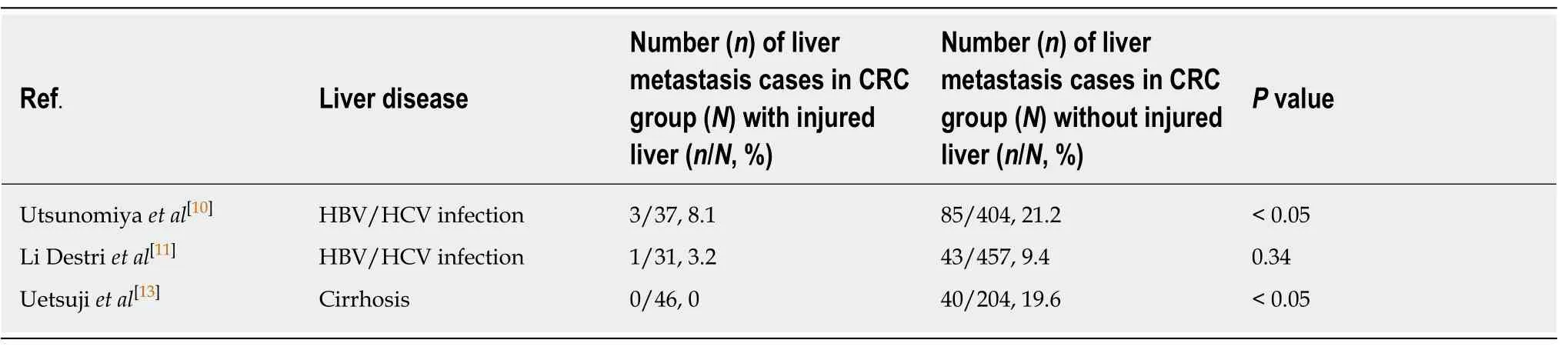

Given the long term for therapeutic course in liver diseases, it is highly possible that the liver immune environment has been altered prior to the occurrence of malignancies[17-19]. Therefore, reduced liver metastasis in CRC could be associated with the altered immune response, which was already triggered by liver diseases.However, up to now, the role of HBV/HCV infected or cirrhotic liver-associated therapy in reducing liver metastasis remains largely unclear. Meanwhile, it is also essential to distinguish the roles of injured liver status and medical therapy targeting HBV/HCV infected or cirrhotic liver, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, it is insightful to perform a trial analyzing CRC patients with an injured liver but without receiving antiviral therapy to illustrate the association between injured-liver status and reduced liver metastasis. Interestingly, CRC patients with an impaired parenchyma (selective right portal vein embolization) did show a smaller volume of liver metastatic lesion compared to the patients with functionally-intact liver parenchyma[20]. Moreover,Augustinet al[21]reported that CRC patients with a chronically injured liver had a significantly lower incidence of liver metastasis than CRC patients without. However,in that study, the role of medical therapy was not disclosed. Collectively, the injured liver status could be an influential factor with reduced liver metastasis.

ANTIVIRAL THERAPY AND IMMUNE SYSTEM

The role of immune system associated therapy, including antiviral drugs (interferon and nucleoside/nucleotide analogues), remains largely unclear in the progression of liver metastasis in CRC[22-24]. Intriguingly, antiviral therapy has been potentially identified to reduce the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma as well as the survival risks[25-27].

Mechanistically, liver targeted antiviral therapy improves the immune status of liver cells, at both the cellular and extracellular matrix levels, enhancing the activities of intrinsic immune cells[28]. The density of CD8+ T cells in tumor was inversely correlated with pathological T stage in CRC without relapse while CD8 + T cell density was low in cases with relapse[28]. In fact, antiretroviral therapy for HIV infections could preserve the HIV-specific function of CD8 + T cells as well as other T cell subsets[29]. Viral persistence enhances Tfh immunity and represses Th1 response[30].Loss of Th1 could specifically reduce the function of CD8 T cell[30]. Therefore, antiviral therapy could avert the repression of both Th1 and CD8 T cells, implying that antiviral therapy could modulate the immunological activity throughout the tumor progression in CRC.

ANTIVIRAL THERAPY AND MICROSATELLITE INSTABILITY IN CRC

Given the clinical benefits of microsatellite instability (MSI) and PD-1/PD-L1 in CRC being increasingly recognized[31,32], this study further discusses the possible effects of antiviral therapy on CRC with MSI or receiving PD-1/PD-L1. MSI, also refers to mismatch repair (MMR), has been one of the key genomic markers in CRC[31]. Based on its genomic status, CRC patients can be stratified as MSI-High, MSI-Low, and microsatellite stable (MSS) groups, similarly to the classification of MMR-deficient(dMMR) and MMR-proficient (pMMR) CRC. CRC patients with MSI present with more favorable survival outcomes than MSS patients[33]. The association among MSI(or MMR) and PD-1/PD-L1, a key immunosuppression mediator that represses Th1 cytotoxic immune response and local immunological surveillance, remains largely unclear but increasingly popular. In fact, the antiviral therapy-supported Th1 cells contribute to the general therapeutic effects intrigued by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.Moreover, given the distinct somatic mutations followed by local immunological surveillance between MSI and MSS, antiviral therapy may further enhance the local immunological surveillanceviathe increased activity of Th1 and CD8 T cells.

Of note, the clinical benefits of immune checkpoint blockade could also be predicted by the MMR status, with an immune-related objective response rate of 40%in dMMR and 0% in pMMR while the immune-related progression-free survival rate was 78% in dMMR and 11% in pMMR[34]. This could be partially explained by the comparably larger number of tumor-associated immunogenic antigens from the somatic mutation of dMMR (MSI), rather than pMMR (MSS), if not all.

However, solid evidence from randomized clinical trials focusing on the role of antiviral therapy in reducing liver metastasis of CRC remains largely vacant. In addition, the heterogeneity between CRC and hepatocellular carcinoma may account for potential confounding bias. Specifically, high serum HBV DNA level is an independent prognostic indicator in hepatocellular carcinoma, instead of CRC[35].

FUTURE CLINICAL IMPLEMENTATION

A pilot trial with a large sample size to validate the survival benefit of antiviral therapy is necessary. The value of antiviral drugs in both CRC with or without hepatitis is yet to be fully characterized. In addition, this review also introduces the insightful idea of preventive therapy. Thus, antiviral therapy could be incorporated to the primary treatment of CRC. However, the association between the molecular features of CRC, such as MSI and MSS, and antiviral therapy also awaits furtherexploration.

Table 1 Metastatic ratio comparison of studies on colorectal cancer patients with injured liver status

CONCLUSION

This review highlights the potential survival benefits of liver targeted antiviral therapy in CRC.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Macrophage activation syndrome as an initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus

- Optical coherence tomography guided treatment avoids stenting in an antiphospholipid syndrome patient: A case report

- Uterine incision dehiscence 3 mo after cesarean section causing massive bleeding: A case report

- Ataxia-telangiectasia complicated with Hodgkin's lymphoma: A case report

- Gastric pyloric gland adenoma resembling a submucosal tumor: A case report

- Reduced delay in diagnosis of odontogenic keratocysts with malignant transformation: A case report