Treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding in left ventricular assist devices: A comprehensive review

Srikanth Vedachalam, Gokulakrishnan Balasubramanian, Garrie J Haas, Somashekar G Krishna

Abstract Left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) are increasingly become common as life prolonging therapy in patients with advanced heart failure. Current devices are now used as definitive treatment in some patients given the improved durability of continuous flow pumps. Unfortunately, continuous flow LVADs are fraught with complications such as gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding that are primarily attributed to the formation of arteriovenous malformations. With frequent GI bleeding, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies are usually discontinued increasing the risk of life-threatening events. Small bowel bleeds account for 15%as the source and patients often undergo multiple endoscopic procedures.Treatment strategies include resuscitative measures and endoscopic therapies.Medical treatment is with octreotide. Novel treatment options include thalidomide, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, estrogen-based hormonal therapies, doxycycline, desmopressin and bevacizumab. Current research has explored the mechanism of frequent GI bleeds in this population, including destruction of von Willebrand factor,upregulation of tissue factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis factor-α, tumor growth factor-β, and angiopoetin-2, and downregulation of angiopoetin-1. In addition, healthcare resource utilization is only increasing in this patient population with higher admissions, readmissions, blood product utilization, and endoscopy. While some of the novel endoscopic and medical therapies for LVAD bleeds are still in their development stages, these tools will yet be crucial as the number of LVAD placements will likely only increase in the coming years.

Key words: Left ventricular assist device; Push enteroscopy; Double balloon enteroscopy;Video capsule endoscopy; Octreotide; Bevacizumab; Gastrointestinal bleeding

INTRODUCTION

Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVAD) are becoming increasingly common for endstage heart failure with 20000+ devices placed a year in over 180 hospitals around the United States and growing[1]. These devices are used either as a bridge to heart transplantation or as definitive, destination therapy, which owe their success in part to continuous flow technology which improves pump durability. Unfortunately,current devices appear to increase the incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding,which is seen in 18-40% of patients that have received an LVAD[2-7]. This is a major contributor to increased morbidity and mortality, where there is a 5-fold increased risk for readmission due to GI bleeding[8]. These episodes lead to recurrent hospitalizations, increased lengths of stay, costs, blood transfusions, and time off anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy, which significantly increases the risk of pump thrombosis and stroke[8]. Furthermore, as many of these patients are being bridged to transplant, the increased number of blood transfusions may lead to higher antibody production (allosensitization), thus limiting the donor pool and prolonging the time to transplant. In this review we aim to summarize current literature addressing the management of GI bleeding in patients with LVADs.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

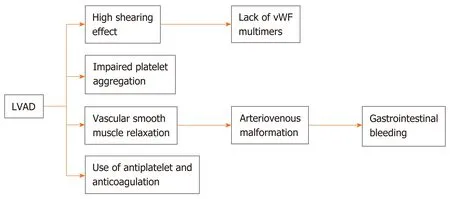

Among all GI bleeding in patients with LVADs, 47% of the episodes originated from the upper GI tract, 22% are from the lower GI tract, 15% are from the midgut(ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve), and nearly 19% remain unknown[5].Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) account for 29%-44% of GI bleeding in this population, and mainly are found in the midgut[5,9]. These lesions can be notoriously hard to treat, as they are frequently multiple lesions throughout the GI tract and bleed intermittently leading to unremarkable endoscopic evaluations[5]. Other common lesions include gastritis (22%), peptic ulcer disease (13%), diverticular hemorrhage(6%), colonic polyps (5%), and colitis (4%), with the remaining causes unknown[10].

Acute GI bleeding management

Medical management: Gastrointestinal bleeding is a significant issue in LVAD patients leading to the discontinuation of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy.Initial management for acute GI bleeding include IV fluid resuscitation, electrolyte replacement, packed red blood cell transfusion to hemoglobin goals of 7-9 g/dL, and discontinuation of antiplatelet (acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and P2Y12 inhibitors) and anticoagulation (Coumadin) medications[14-16]. After an acute episode, antiplatelet drugs may be restarted and anticoagulation may be rechallenged with either the same International Normalized Ratio (INR) goal (typically 1.5-3.5) or at a reduced goal[17,18].Those patients with a high frequency of GI bleeding may have both antiplatelet and anticoagulation medications discontinued for an extended period of time, thus imparting significant risk for LVAD thrombosis.

While present day continuous flow devices have several advantages over the older pulsatile pumps, they have been implicated in the higher risk for the formation of AVMs and increased GI bleeding. It is thought that continuous flow LVADs lead to intestinal hypoperfusion, local hypoxia, vascular dilation, and AVM formation[19]. One technique that can be instituted to reduce GI bleeding is reducing the pump speed under ECHO guidance to increase pulsating flow while ensuring adequate LV offloading[5]. One study looking at the factors of GI bleeds in LVAD patients found decreases in GI bleeding rates with only small decreases in pump speed (HeartMate II 9560 rpmvs9490 rpm,P< 0.001; HeartWare 2949 rpmvs2710 rpm,P< 0.001)[20].

Other conservative management strategies for active GI bleeding and prevention of future episodes include prophylactic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and reversal of anticoagulation. PPIs are often prescribed to LVAD patients, especially when they have had prior episodes of GI bleeding. However, the risk reduction of further GI bleeding is marginal as the majority of bleeding are from AVMs. PPI use was similar between those that did have GI bleeding versus those that did not in a study observing 101 LVAD patients (P= 0.47)[18].

Reversal of anticoagulation is typically done with a combination of vitamin K (oral or IV), fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and/or prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC).There is currently a lack of high-quality, prospective large-scale studies providing recommendations on specific regimens and dosings. However, one review article on anticoagulation reversal has suggested using IV vitamin K and PCC in hemodynamically significant bleeding[21]. Since FFPs require crossmatching, time for thawing, increased volume per unit administered in a fluid sensitive population, and have a higher risk of transfusion-related reactions, PCC is preferred for reversal of anticoagulation[21]. Ultimately, there remains high variability of dosages used throughout the literature, and differing indications for reversal of anticoagulation which often remains largely at the discretion of the treating provider. Following the reversal of anticoagulation, varying rates of thromboembolic events have been reported. While older studies utilizing recombinant activated factor VII at “highdoses” (30-70 μg/kg) revealed thromboembolic event rate of 36.7%[22], more recent literature quote rates of 2.9% (1 of 38) and suggest that larger doses of reversal agents can still have low rates of thromboembolism[4].

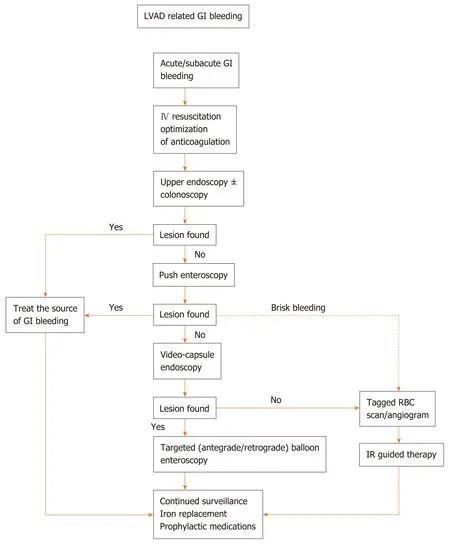

Endoscopic therapy: A treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 2. Endoscopic evaluation and treatment is frequently performed in LVAD patients given their high rates of GI bleeding. Most patients will receive an esophagogastroduodenoscopy(EGD) and/or colonoscopy on the initial presentation with concerns for GI bleeding.If these evaluations are unremarkable, the next step would be to consider a repeat EGD, given the high rates of upper GI bleeds, with possible push enteroscopy to explore small bowel sources, and repeat a colonoscopy if the initial colonoscopy prep was suboptimal[7,16].

Push enteroscopy allows for evaluation of the small bowel; most commonly to the proximal jejunum. Marsanoet al[23]found that EGD had high rates of detection (45%),however many required repeat endoscopy at a rate of 1.8 endoscopes per patient in their study. On repeat endoscopy the majority underwent push enteroscopy with a high small bowel detection rate of 80% in repeat bleeding episodes with 25% of their patients having jejunal lesions[23].

Figure 1 Pathophysiology of gastrointestinal bleeding in left ventricular assist device patients. LVAD: Left ventricular assist device; vWF: von Willebrand factor.

A significant portion of LVAD-related GI bleeding come from the midgut/unknown origins, which makes evaluation of the small bowel important in this population. While there may be some conflicting data that balloon (single or double)enteroscopy is superior, however, according to the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines, it is still recommended to proceed with video capsule endoscopy (VCE) as first line evaluation of the small bowel[15]. This is a safe technique with no electromagnetic interference to LVADs or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) devices[24]. One study showed initial VCE had a diagnostic yield of 58.5% versus proceeding with double balloon enteroscopy first that had a yield of 41.5%[25]. Not only does VCE have a greater diagnostic yield, but it also is helpful in deciding the subsequent endoscopic approach based on the presumed location of the bleed. Further, there is an increased overall yield of 7% with double balloon enteroscopy if done after VCE[25].

The black wretch! said Anne Lisbeth, he will end by frighteningme today. She had brought coffee and chicory with her, for shethought it would be a charity to the poor woman to give them to her to boil a cup of coffee, and then she would take a cup herself.

Double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) allows clinicians to use a “push-and-pull”technique to visualize the small bowel. In the realm of obscure GI bleeding, the diagnostic yield of this technique was found to be 56% (95%CI: 48.9%-62.1%) in one large meta-analysis[26]. Specifically in LVAD patients with GI bleeding, the diagnostic yield with DBE was 69%[27]. In this study, 10 patients underwent 13 DBEs for 11 episodes of melena and 2 episodes of hematochezia. Mid-bowel lesions were found 56% of the times, while 33% of lesions were in the proximal bowel, and 11% were in both proximal and mid-bowel. The most common lesions identified were AVMs,consisting of 44% of the discovered lesions.

AVMs are often found in LVAD patients and are commonly treated with contact or non-contact thermal therapy [argon plasma coagulation (APC)] given the large,diffuse nature of these lesions[16]. One study showed that APC treatment of colonic AVMs could significantly decrease blood transfusions and increase overall hemoglobin in a 16-mo follow-up[28]. However, the upper/midgut predominance of AVMs in LVAD patients versus the classic right colonic location of AVMs in non-LVAD patient may change the nature of these AVMs. In addition, the tendency of increased anticoagulation in LVAD patients may cause APC to be less effective in LVAD patients, and may even provoke future bleeding episodes as APC can cause ulceration[29]. Clinicians should carefully consider the use of APC in LVAD patients,and may benefit from alternative methods to control bleed endoscopically or with the medical therapies discussed below. According to the European Society of Gastroenterology (ESGE), there is not enough evidence to prescribe treatment recommendations for AVM lesions at this time[14].

Apart from thermal therapy, other endoscopic treatment options for AVMs and other sources of GI bleeding found in LVAD patients include epinephrine injection,electrocautery, endoclips, band ligation, acrylic glue and hemostatic spray/powder[15,16,30,31]. With large bleeding ulcers, it is recommended to approach these lesions with “dual therapy”, typically with epinephrine and another modality[14].Hemostatic spray is currently not seen as “conventional” therapy and used in setting of “salvage” therapy[24,30]. One study looking at TC-325, hemostatic powder, showed a 90.7% primary hemostasis rate with a rebleeding rate of 26.1%. It was, however, found to be less effective in patients on anticoagulation, like LVAD patients, with a hemostasis rate of 63%[30].

Figure 2 Treatment algorithm for left ventricular assist device-related gastrointestinal bleeding. Angiogram and tagged RBC scan are two common imaging modality to elucidate locations of bleed for further intervention. Iron deficiency is a common with chronic hemolysis in left ventricular assist device patients. Iron replacement can be initiated after checking iron studies. LVAD: Left ventricular assist device; GI: Gastrointestinal.

Prophylactic medications: Arteriovenous malformation targeted medical therapy

The diffuse nature AVM are responsible for many cases of bleeding/rebleeding in LVAD patients; up to 29%-44%. Endoscopy may be able to identify an acutely bleeding lesion, but one bleeding AVM lesion usually portends others along the GI tract that may bleed in the future, as well as the formation of new AVMs. Therefore,medical therapy targeted at the driving factors of these lesions have been used to reduce the episodes of rebleeding and ultimately decrease the number of hospitalizations, endoscopic procedures and blood transfusions.

Octreotide: After conservative medical therapy is tried and failed, a common first agent that is used to reduce recurrent GI bleeding in LVAD patients is octreotide, a somatostatin analogue. It is believed that octreotide reduces bleeding rates by decreasing portal venous pressures due to splenic vasodilation, enhancing platelet aggregation, and inhibiting of angiogenesis in the GI tract through downregulation of VEGF and suppression of digestive enzymes[5,32]. Octreotide is currently dosed 50 to 100 μg subcutaneous (SQ) twice daily (BID) or octreotide long-acting release (LAR) 20 to 30 mg intramuscularly (IM) monthly. A study observing the effects of octreotide LAR 20 mg IM monthly in LVAD patients showed a significant reduction of bleeding events in their 26 patient cohort (20 Heartmate II, 5 HVAD, and 1 HeartAssist). The average number of bleeding episodes pre-treatment was 3 ± 2.4 per year in this group with improvement to 0.7 ± 1.3 per year after initiation of monthly octreotide. 43% of the cohort was free of further bleeding episodes in follow-up[13]. Furthermore, AVM lesions were found 44% of the times on endoscopy prior to octreotide therapy, but only 28% of the times afterwards.[13]Long acting 20 mg depot octreotide has also been studied in a prophylactic setting started within 1 mo of LVAD implant in a phase I trial of 10 patients that prevented any GI bleeding episodes within the first four months when otherwise typical rates are 39% within the first 2 mo after implantation[32,33].

Octreotide is seen currently as the first line agent, but does have some potential side effects that need to be discussed with patients. These side effects include diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, gallstone formation, glucose abnormalities, pruritis, hypothyroidism, headaches and dizziness[34].

Thalidomide: Thalidomide has been used for several indications over the years since it was initially synthesized in the 1950s, including for morning sickness, sedation, and Kaposi sarcoma treatment. LVAD patients have benefited from thalidomide for its anti-angiogenesis effect through its ability to downregulate VEGF and basic fibroblastic growth factor (bFGF)[35]. This has been shown to reduce the rate of recurrent AVM-related bleeds. In a study that tested thalidomide 100 mg daily versus iron supplementation daily (control) in non-LVAD patient for four months showed a 50% or greater reduction in the rate of GI bleeding in 71.4% of patients on thalidomide versus only 3.7% in the control group over a one year follow-up. 46.4% of patients in thalidomide arm had complete cessation of further bleeds versus 0% in the control arm[35]. Recently, a 2019 study of 17 LVAD patients receiving thalidomide showed favorable results with a reduction of GI bleeding from an average 4.6 episodes per year to 0.4 episodes per year. Additionally, blood transfusions reduced from 36.1 to 0.9 units of transfusions per year. In this study 50 mg of thalidomide was used daily or twice daily with uptitration to 100 mg twice daily with bleeding episodes[6].

However, there are some notable shortcomings with thalidomide. Thalidomide has been shown to have a relatively high adverse event rate; ranging from 58-71%[6,36]. The more common adverse events encountered were dizziness, neuropathy, fatigue,constipation, transaminitis, and somnolence. There does seem to be dose-dependent response in adverse effects with 87.5% of patients improving with lower doses of thalidomide. Additionally, access and cost are both seemingly issues. Thalidomide is generally cost-prohibitive if not covered by insurance, and prior authorization is typically needed; delaying drug initiation. In Namdaranet al[6], bridging with octreotide was used on average for 11 d while approval was received and could be used as a workaround. Finally, both prescriber and pharmacist need to be approved by the THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program to prescribe the thalidomide, which limit the number of providers that can offer this therapy.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers:

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers(ARBs) are common cardiac medications that appear to have a benefit in preventing recurrent GI bleeding in LVAD patients. Houstonet al[3]looked at 131 LVAD patients and recorded whether or not they were on an ACEi or ARB for at least 30 days with LVAD support. This study found that of the 31 patients that did not receive an ACEi or an ARB, 48% had a GI bleeding episode with 29% of those being related to AVMs;while only 24% of those that received an ACEi or ARB had GI bleeding and only 9%were related to AVMs. Ultimately, an OR 0.29 for all causes of GI bleed, along with an OR 0.23 for AVM bleeds were found. It is thought the mechanism mainly centers around the downregulation of TGF-β, which normally upregulates VEGF. In addition,these agents create a blockade of angiotensin-II from acting upon angiotensin I receptors, causing a downregulation of the angiogenesis.

Their study also looked at dosing of these medications and failed to show a dosedependence on its ability to reduce AVM-related bleeds[3]. The effect of ACEi/ARB on AVM lesions seem to be separate to its blood pressure effect as beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers independently tested in LVAD patients did not produce the same results in decreasing the number of GI bleeds that ACEi/ARBs were able to.Additional studies are needed to validate the effect of ACEi/ARBs in this population.Estrogen-based hormone therapy: Hormone therapies, either estrogen-only or estrogen in combination with progesterone, have been studied in the prevention of AVM bleeds with conflicting results. One multicentered, randomized, controlled trial studied 72 non-LVAD patients that used ethinylestradiol 0.01 mg daily and norethisterone 2 mg daily versus placebo for at least a year. This trial did not show a significant difference between the two arms. Treatment failure rate was 39%vs46%between hormone therapy and control, respectively. Likewise, the number of bleeding episodes, transfusion requirements, severe adverse events and mortality did not differ significantly between groups[37]. Contrarily, isolated case reports have evaluated individual LVAD patients with remarkable results reducing frequent GI bleeds through the use of estrogen-based therapies[35,38]. Overall, the benefits of hormone therapy are theorized to be caused by improved vascular endothelium integrity and reduced bleeding times[5]. The literature available for hormone therapy in LVAD patients is very sparse. Furthermore, the concerns for thromboembolism with estrogen-based therapies will likely give pause to many practitioners in this already pro-thrombotic population without further large-scaled studies.

Doxycycline: Doxycycline is a relatively inexpensive medication that is widely used in both the short-term setting to treat pneumonia to chronic management in inflammatory acne. Bartoliet al[11]conducted anin vitrostudy looking at the prospect of using doxycycline to reduce LVAD bleeds by stabilizing ADAMTS-13[11]. High shear stress was added to human plasma samples with high doses of doxycycline (0.6 to 20 mg/dL). vWF degradation was greatly diminished with 10 out of the 11 degradation fragments reduced from baseline by 12% ± 2% when doxycycline was added. It was found that doxycycline reduced the plasma and recombinant forms of ADAMTS-13 activity in these suprashear stress environments. Additionally,vWF:collagen binding was increased with doxycycline and resulted in overall improved platelet aggregation without hyperactivating platelets to increase thrombosis formation. This showed promisingin vitroresults, but dosages of doxycycline that were effective ranged from 5-20 mg/dL, which far exceeds the 0.3 to 0.5 mg/dL most patients receive today. While this is below toxic limits of 2000 mg/kg in rat models, further testing will surely need to occur before this therapy becomes mainstream. To date, there is sparse other data on doxycycline use in LVAD patients.Desmopressin: Desmopressin is a vasopressin analog that is currently approved for use in patients with either hemophilia A or mild-to-moderate von Willebrand disease(type I), and may also have its use in LVAD patients to reduce GI bleeding[39]. There are isolated case reports of achieving control of GI bleeding secondary to LVAD[2].vWF multimers are in gross deficit in LVAD patients, as noted in this review.Desmopressin has the ability to increase the amount of vWF by 150%-200% at the 150 mcg dose[2]. Although, there are potential adverse effects of hyponatremia and fluid retention with desmopressin, which can be detrimental to patients with poor rightsided cardiac function and may require intensified oral diuretic regimens[2]. Overall,this medication still shows promise. Again the literature is sparse and larger studies are needed.

Bevacizumab: Preliminary results from a single institutional study show remarkable results from bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF, in lowering the rate of GI bleeding in refractory cases[40]. This study evaluated 5 patients with LVADs and showed annual decreases in blood product usage from 45.8 to 6.0 units, reduced hospitalizations per year from 5.6 to 1.7 and an annual reduction in endoscopy from 10.6 to 2.3 procedures. Bevacizumab was well tolerated without side effects in the study participants. As with other novel agents, further studies are necessary.

CONCLUSION

GI bleeding is a frequent complication of LVAD placement due to the continuous flow LVAD devices causing dysregulation of angiogenesis-related biomarkers and sheer stress. Conservative methods such as reducing anticoagulation doses and discontinuing antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies are unsafe and not successful in most instances. The AVMs are frequently located in the midgut and pose challenges with routine endoscopy. Video capsule endoscopy has a high diagnostic yield and should be performed after unremarkable EGD and colonoscopy in most cases. Afterwards, prompt push enteroscopy, or DBE is recommended to treat lesions before they stop bleeding, as well as to reduce the number of blood products transfused in LVAD patients. Octreotide is a commonly used medication in GI bleeding and is the first line agent for those with refractory bleeding. ACEi/ARB may have secondary benefits in reducing AVM-related bleeding. Some case studies indicate the role of estrogen-based hormone therapies, doxycycline, and desmopressin. Other medications with significant side effects need to be evaluated in larger studies, including thalidomide and bevacizumab. With the increase of durable LVAD placements each year, we will manage more frequent instances of GI bleeding,and it will be important to continue to refine diagnostic and therapeutic methods to treat and prevent these episodes.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年20期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年20期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy – Too often? Too late? Who are the right patients for gastrostomy?

- Decreased of BAFF-R expression and B cells maturation in patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma

- Anhedonia and functional dyspepsia in obese patients: Relationship with binge eating behaviour

- Clinicopathological features of early gastric cancers arising in Helicobacter pylori uninfected patients

- Role of gut microbiota-immunity axis in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer: Focus on short and long-term outcomes

- Diet in neurogenic bowel management: A viewpoint on spinal cord injury