Effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy with sulfadoxinepyrimethamine: An in silico pharmacological model

Mila Nu Nu Htay, Ian M Hastings, Eva Maria Hodel,3,4, Katherine Kay,5

1Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool L35QA, United Kingdom

2Department of Community Medicine, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), Melaka, Malaysia

3Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme, Blantyre, Malawi

4University of Liverpool, Liverpool L693GF, United Kingdom

5Metrum Research Group , Tariffville, Connecticut, 06081, United States of America

ABSTRACT Objective: To explore the efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine(SP) against sensitive parasites.Methods: A pharmacological model was used to investigate the effectiveness of the previous recommended at least two-dose regimen, currently recommended three-dose regimen and 4, 6,8-weekly regimens with speci fic focus on the impact of various nonadherence patterns in multiple transmission settings.Results: The effectiveness of the recommended three-dose regimen is high in all the transmission intensities, i.e. >99%, 98% and 92%in low, moderate and high transmission intensities respectively.The simulated 4 and 6 weekly IPTp-SP regimens were able to prevent new infections with sensitive parasites in almost all women(>99%) regardless of transmission intensity. However, 8 weekly interval dose schedules were found to have 71% and 86% protective efficacies in high and moderate transmission areas, respectively. It highlights that patients are particularly vulnerable to acquiring new infections if IPTp-SP doses are missed.Conclusions: The pharmacological model predicts that full adherence to the currently recommended three-dose regimen should provide almost complete protection from malaria infection in moderate and high transmission regions. However, it also highlights that patients are particularly vulnerable to acquiring new infections if IPTp doses are spaced too widely or if doses are missed. Adherence to the recommended IPTp-SP schedules is recommended.

KEYWORDS: Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy;Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine; Malaria infection in pregnancy; Threedose regimen; In silico pharmacological model

1. Introduction

An estimated 216 million malaria cases occurred globally in 2016,where 90% of the cases occurred in Africa[1]. To minimise the health impact of malaria on pregnant women and their unborn babies,the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxinepyrimethamine (SP) for pregnant women in Sub-Saharan African countries with stable malaria transmission[2]. Other strategies such as IPTp with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP) are currently under evaluation and appeared to be effective[3], however, IPTp-SP remains the WHO recommended regimen in Sub-Saharan Africa[4].IPTp-SP is well tolerated in pregnancy, highly efficacious and known to reduce malaria-associated risks factors such as severe maternal anaemia[5], placental malaria[6], low birth weight[5,7]and infantile deaths[8]. Its effects are two-fold: (i) curing existing malaria infections (treatment effect) and (ii) preventing new infections (prophylactic effect) through its long half-life[9]. In 2004,

WHO recommended to provide at least two doses of IPTp-SP during the scheduled antenatal care (ANC) visits[10], which was amended focusing to provide three doses throughout the pregnancy in 2013[4].The presence of thePlasmodium falciparumdihydropteroate synthase A581G mutation and the dihydropteroate synthase K540E mutation has been associated with a reduction in effectiveness of IPTp-SP[11]. Although, there is a potential alternative such as IPTp-DP, recommendation policy changes might take time to implement and there is concern about using a potential first-line drug for IPTp.Consequently, IPTp-SP is currently the only recommend regimen.Therefore, it is crucial to quantify the effectiveness of the IPTp-SP for three-dose regimen to compare with that of 4, 6 and 8 weekly regimens during the second and third trimester.

There are a number of difficulties when quantifying the effectiveness of IPTp-SP. The first is attributed to SP’s varying ability to prevent new infections when local malaria transmission intensity differs[12], so it is crucial to consider the impact of transmission intensity on IPTp-SP efficacy. A second potential problem is the reportedly low uptake of IPTp-SP despite its proven bene fits, which is a serious concern as SP is given as a single dose so adherence, at least under ideal conditions, should be high. The alternative IPTp-DP needs to be taken as a three-day regimen, which might be a burden on pregnant women and can led to poor adherence[13]. The effectiveness of the IPTp-SP regimens is investigated here with speci fic focus on the impact of various non-adherence patterns in multiple transmission settings.

In silicopharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models are powerful tools that can predict the efficacy and effectiveness of antimalarial drugs used for treatment or prevention[14-16]. These pharmacological models are particularly attractive because it can predict the drugs’ effect at far lower cost, over a wider range of conditions and in shorter time than clinical trials. Furthermore, the models can easily account for factors such as transmission intensity and patient adherence. This study used a previously published PK/PD model[14] which has been slightly modi fied and calibrated to explore the efficacy of IPTp-SP against sensitive parasites.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. PK/PD model

Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine are known to act on the Plasmodium parasites in synergy, i.e. their combined effect is greater than the sum of each drug given alone. Incorporating this synergistic effect into PK/PD models is challenging and therefore has not been attempted previously.

The effectiveness of SP when used in IPTp programs was simulated using an extended version of the PK/PD model[14]. The model tracks parasites number as a function of parasite growth and changing drug concentration over time. The extension of this model allows for the inclusion of synergistic effect of SP. To simulate IPTp treatment,the probability of acquiring a new infection was determined in each of the 1000 pregnant women simulated. Infections were assumed to be fully sensitive to SP treatment and the effects of transmission intensity and patient adherence on the prophylactic ability of SP were assessed.

The change in parasite number over time was found using the standard differential equation[17]

wherePis the number of parasites in the infection,tis time after treatment (days),ais the parasite growth rate (1.15 per day),f(I)is the host background immunity andf(C)represents the drugdependent rate of parasite killing. It was assumed that pregnant women did not have protective immunity [f(I)=0] (see later discussion).

Equation 1 was integrated using the separation of variable technique[18] to predict the total number of parasites at any time point,Pt, after treatment as

whereP0is the number of parasites at the time of treatment (i.e.t=0). When validating the model, data from therapeutic studies was used, so parasites were assumed to be present, and patent, at the time of treatment and soP0was chosen from a uniform distribution between 1010and 1012. When simulating IPTp clinical trials, it was assumed there was no existing infection at the time of treatment but that 105parasites could emerge from the liver to cause a new infection during the follow-up. An infection was assumed to have been cleared by the drug ifPtfell below 1 at any time post-treatment.The drug killing ratef(C)for SP treatment is:

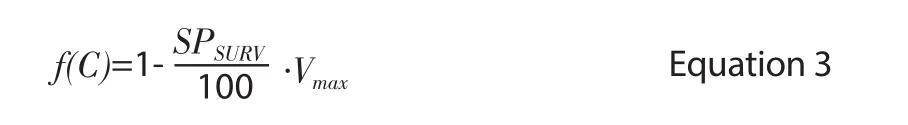

Where theVmaxis the combined maximal parasite kill rate of SP and represents the percentage of malaria parasites surviving SP treatment(see below).

TheVmaxcan be calculated from the parasite reduction ratio (PRR)as follows

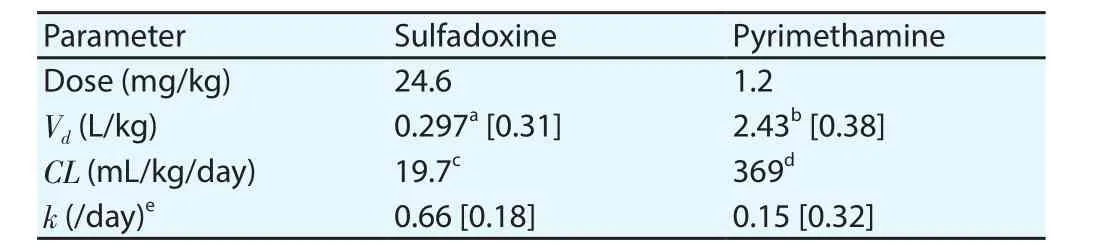

The concentrations of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine at timetwere found for both drugs individually using the methods described in Equation 3[14], which assumes instantaneous absorption, one compartment disposition and linear elimination. While it is known that sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine act synergistically, there is currently no consensus method of modelling drug synergy. InsteadSPSURVwas estimated using the response surface for drug sensitive parasites; previously described by Gattonet al.(Figure 1A of[19]).To replicate the percentage of parasites survivingin vivo, the amount of drug required to produce an effect in the originalin vitroresponse surface was increased two-fold to produce the new response surface shown in Figure 1 and subsequently used to estimate the percentage of parasites surviving treatment for any simulated drug concentration. For each simulated sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine concentration within the response surface range, the proportion of parasites surviving was calculated from the nearest grid point using vector geometry. For concentrations outside the response surface range, the concentration was assumed to be equal to the outermost isobole and vector geometry was again used to find the survival value. The model was implemented in R software package (version 3.1.0).

2.2. Model calibration and validation

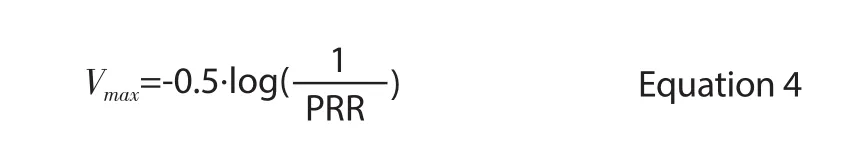

The pharmacokinetic component of the model required estimates of the volume of distribution (Vd) and elimination rate constant (k) for sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine. These were taken from a published clinical trial[20], where pregnant women received 24.6 mg/kg of sulfadoxine and 1.2 mg/kg of pyrimethamine, twice during the study(Table 1). Inter-patient variation in PK parameters was incorporated into the model using parameter speci fic estimates of the coefficient of variation (CV) and variability was assumed to be normally distributed. The estimates for k were calculated based on drug clearance rates (CL) was measured in a field-based pharmacokinetic study of SP in healthy adult volunteers[21].

The PK parameters were validated against a PK study in pregnant women[20]; the simulated maximum drug concentrations (Cmax)and concentration on day 7 (C7) were found to closely match field data when using the parameters in Table 1. Sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine were assumed to be instantaneously absorbed (a reasonable approximation for drugs with a long half-life[15] and so the time to reachCmax(Tmax) occurred immediately after dosing and was thus excluded from the validation process.

As sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine were assumed to work synergistically, the proportion of parasites killed was determined directly from the response surface (Figure 1). Therefore, the only PD parameter required for the model was an estimate of the combined maximal parasite kill rate (Vmax). This was estimated using Equation 4 and a PRR of 100[22] with a CV of 30%. The PD component was validated against the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) corrected cure rate measured in African children with uncomplicated falciparum malaria[23]; the simulated cure rate of 97.7% (after a single treatment dose, using PK parameters as in Table 1) closely matched the study results of 99%.

Table 1. Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters and treatment dose for sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine.

Figure 1. The synergistic effect of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine on parasite survival. The response surface used to estimate the percentage of parasites surviving treatment for any simulated drug concentration was estimated from the original in vitro response described in Figure 1a of[19] after applying the two-fold modi fication described in the methods above. Note concentrations of sulfadoxine (SD) and pyrimethamine (PM) were plotted on a log scale.

2.3. Simulations of IPTp-SP effectiveness

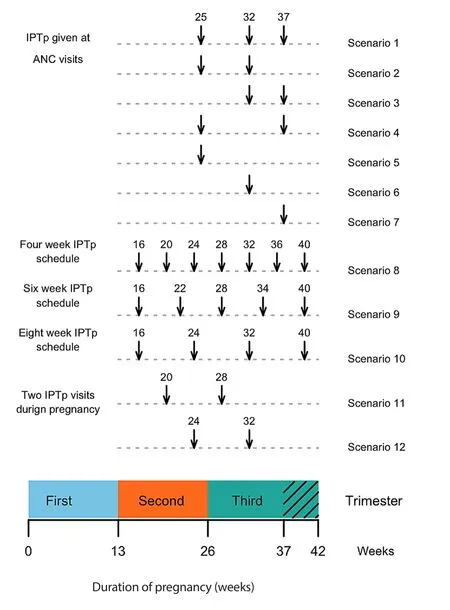

Simulations were used to predict the effectiveness of IPTp-SP in different scenarios (Figure 2). Two-dose, three-dose and dosing at 4,6,and 8-week intervals were investigated to compare the protective efficacy of the previous[10], current recommended schedules[4] and to explore more frequent IPTp doses at least one month interval apart.The impact of poor patient adherence missed doses or receiving IPTp only in the third trimester was considered for the threedose treatment schedule. Twelve scenarios were examined in total(described on Figure 2) as follows:

·Scenario 1: Full adherence to three-dose regimen

·Scenario 2: Receiving first two doses (i.e., third dose missed)

·Scenario 3: Receiving last two doses (i.e., first dose missed)

·Scenario 4: Receiving first and last doses (i.e., second dose missed)

·Scenario 5: Receiving first dose only

·Scenario 6: Receiving second dose only

·Scenario 7: Receiving third dose only

For the 4, 6, 8-weekly regimens to be given in second trimester

·Scenario 8: Four-weekly IPTp doses

·Scenario 9: Six-weekly IPTp doses

·Scenario 10: Eight-weekly IPTp doses

And for the two-dose IPTp regimen

·Scenario 11: Two-dose IPTp (i.e., week 20 and 28)

·Scenario 12: Two-dose IPTp (i.e., week 24 and 32)

IPTp-SP treatment was simulated in 1000 pregnant women,initially uninfected, women using the model described above. The model was run in one-day time steps and the expected date of delivery ranged between 37 to 42 weeks of pregnancy[24]. The exact length of each simulated pregnancy was chosen at random from a uniform distribution. Each woman was assigned pharmacokinetic parameters according to the distributions given in Table 1. Each day after 16 weeks of pregnancy, 105parasites were assumed to emerge from the liver and the fate of the clone was recorded by noting whether it would eventually survive to form a viable infection. The new infections were deemed to have survived if parasite density increased to detectable levels (108) and cleared if the number of parasites fell below one. This provided a distribution of the days each woman was potentially vulnerable to acquiring a new infection(herein referred to as ‘vulnerability distribution’).

Women are highly unlikely to have a new infection emerging from the liver every day so the protective effect of IPTp was used to investigate low, medium and high transmission settings. Carneiroet al. 2010[25] de fined the expected entomological inoculation rate(EIR, measured as infectious bites per year) in low, medium and high transmission areas as 1-10, 10-100 and 100-200, respectively.Here low, medium and high transmission was defined as EIR of 1, 10 and 100, respectively. The specific number of bites was scaled according to the length of pregnancy and the speci fic day on which bites occurred was randomly assigned according to a Poisson distribution. The fate of each bite was determined from the ‘vulnerability distribution’ and used to produce three new distributions (one per transmission setting) describing the proportion of women infection-free during pregnancy and, in women who do acquire a new infection, the earliest day the infection emerged.These new distributions were then used to plot Kaplan Meier (KM)curves to investigate the protective efficacy of each IPTp adherence scenarios in the three transmission settings. The log-rank test was used to determine whether the KM curves of different scenarios were signi ficantly different.

Figure 2. The adherence scenarios simulated for sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine intermittent preventative treatment in pregnancy (IPTp). The duration of pregnancy (in weeks and trimesters) are shown at the bottom of the plot.Black arrows indicate the timings of IPTp-SP doses for recommended IPTp schedules with each row representing a different adherence scenario.Simulated patients were given three doses of IPTp-SP as currently previously recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013[4], or two doses of IPTp-SP as previously recommended by the WHO in 2004 and 4,6, 8 weekly doses of IPTp[4]. Full adherence is shown in rows Scenario 1,8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 respectively, patterns of poor adherence are shown in the subsequent rows.

3. Results

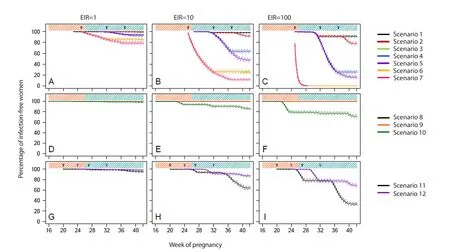

The KM curves for recommended IPTp regimens are shown in Figure 3. For the three-dose regimen, treatment begins at 25 weeks of pregnancy. The effectiveness of the recommended three-dose regimen is high in low and moderate transmissions areas, where it prevents new infections in more than 98% of women. This regimen still has high protective efficacy even in high transmission areas which is about 92% (panel A-C, Figure 3).

For the simulations of full adherence to four, six and eight weekly regimens (Scenario 8, 9 & 10), the former two regimens provide protection to >99% of pregnant women throughout the second and third trimester, regardless of the level of malaria transmission (panel D-F, Figure 3). However, eight-weekly regimen simulated results reveal that the percentage of women who do not acquire a new infection drops to 71% in high transmission area, whereas it is 99%and 86% respectively in low and moderate transmission intensities(panel D-F, Figure 3).

The coloured lines in Figure 3 show the effects of missed IPTp doses. Missing IPTp doses in the second trimester (Scenarios-3,6, 7) has a much greater impact on the protective ability of IPTp than missing doses in the third trimester (Scenario-2, 5). For the three-dose regimen, the percentage of women without an infection is reduced from >99% if the third dose is missed (Scenario-2) to 86% if the first dose in second trimester is missed (Scenario-3) in areas of low transmission, 90% (Scenario-2) to 26% (Scenario-3)in areas of medium transmission, and from 78% (Scenario-2) to 0%(Scenario-3) in areas of high transmission. It can be clearly seen that missing treatment during the second trimester (Scenario-3) reduces the percentage of women protected throughout pregnancy more than missing doses in the third trimester (Scenario-2, panels A-C, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves. The percentage of women given intermittent preventative treatment in pregnancy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP) and who remain infection free over the second and third trimesters of pregnancy when given (i) the currently recommended three-dose regimen ([9]; top panels) or (ii) 4, 6,8 weekly regimens (middle panels) or (iii) the previously recommended two-dose regimen ([15]; bottom panels). The panel columns show how the effectiveness of IPTp regimens change as the entomological inoculation rate (EIR) increases from 1 (left panels), to 10 (center panels), to 100 (right panels). The black arrows indicate the timing of recommended IPTp-SP doses in the second trimester (orange-shaded region) and third trimester (blue-shaded region). The solid black line on top panels represents full adherence while the coloured lines on that panel represent the effect of missed doses. Each colour line represents a speci fic scenario in middle and bottom panels (see Figure 2 and main text for more details).

If the pregnant women received only one dose in the second trimester(Scenario-5), the protective efficacies are 92% in low, 48% in moderate and 16% in high transmission areas. When IPTp was taken only as a single dose in the third trimester (Scenarios-6 and 7), the KM curves show that >99% of women had acquired a new infection by the end of the second trimester in medium transmission settings and all women had at least one new infection in high transmission areas. This result does not mean that there is no bene fit to taking IPTp in the third trimester only, it simply highlights the importance of taking IPTp as early as possible in the second trimester.

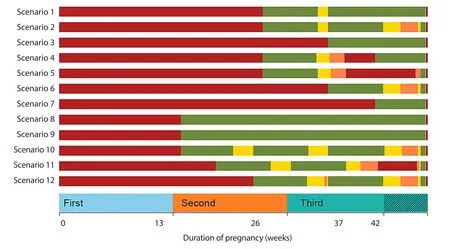

Figure 4. Proportion of women protected by intermittent preventative treatment in pregnancy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). Simulated patients were given either three doses of IPTp-SP as currently recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)[4] or 4, 6, 8 weekly-doses of IPTp or two doses as previously recommended by the WHO[10] with each row representing a different adherence scenario (Scenario 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) full adherence is shown in rows Scenario 1, 8, 910, 11 and 12 respectively. For illustrative purposes, the proportion of women protected at each time point was arbitrarily categorised as >95% (green), >75 to 95% (yellow), >50 to 75% (orange) and ≤50% (red).

If the KM curves had been illustrated from the time of the first dose in the third trimester, the figures would have shown that IPTp is still able to prevent all infections after treatment begins and until patients give birth, but that the protective period would be dramatically reduced (Figure 4). Two-dose regimens were simulated in the model,providing two doses IPTp-SP during the second trimester (at 20 and 28 weeks) (Scenario-11) and the first dose in second trimester(at 24 weeks) and the second dose in third trimester (at 32 weeks)(Scenario-12). Missing the dose in the third trimester decline the protective efficacy from 87%, 69% (Scenario-12) to 64%, 33%(Scenario-11) respectively in moderate and high transmission areas.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated reduced efficacy of SP in high prevalence, SP-resistance areas[26], but SP remains the main recommended regimen to prevent the complications of malaria in pregnancy. Me floquine has the long half-life required for IPTp treatment but adverse effects make it an unattractive alternative[4].Artemether-lumefantrine has also been investigated as intermittent screening and treatment in pregnancy, however, intermittent screening and treatment in pregnancy-artemether-lumefantrine did not provide better outcomes of malaria infection in pregnancy[27].Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine is a potential drug combination to be used as the IPTp. A systematic review of IPTp-DP revealed that monthly dosing has efficacy of 84% reduction of malaria parasitaemia and provided better protection compared to the 2 or 3 monthly regimens[3]. Further studies of monthly IPTp-DP should explore issues surrounding cardiac safety and safety for pregnant women[3]. Use of IPTp-DP could potentially provide an alternative to IPTp-SP in the future[28] but has not been officially recommended yet. There are concerns about resistance to piperaquine, which may have arisen in South-East Asia and a three-day regimen might cause poor adherence to the full course[29].

This PK/PD model assumed that patients had no immunity and received no additional antimalarial medication throughout the simulated pregnancy period. These were realistic assumptions as it is known that immunity is reduced in pregnancy and women were removed from the KM analysis if they acquired a new infection. In effect, the model provides the ‘worst-case’ predictions of IPTp-SP effectiveness against sensitive parasites as any infection is treated as a treatment failure. In reality, women can retain some residual immunity from previous placental malaria infections[30].

One limitation of the current work is the response surface used to quantify the synergistic effect of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine.To date there is no mathematical equation available that describes SP synergyin vivounder physiological conditions and at therapeutic concentrations. The current study therefore used a very simple approach to estimate parasite survival under SP by assuming all parasites are equally sensitivity to SP as de fined by Figure 1 and so variability in parasite sensitivity was incorporated through variability in the PRR/Vmaxonly (unlike previous analyses of other drugs where variation in IC50could also be included). Unfortunately,the limited concentration range and lack of field data meant the model could not be likewise validated for resistant parasites using a similar isobologram generated with data from resistant parasites.This means it is not currently possible to fully incorporate the effects of parasite variation in SP sensitivity in terms of the IC50s to each individual drug nor the threat posed by the presence of resistance.Future laboratory-based studies are needed to get better estimates of parasite survival rates for sensitive and resistant genotypes under different SP concentrations.

The timing of the three-dose IPTp regimen is scheduled concordance with WHO recommended antenatal visits. The threedose regimen is highly protective against malaria infection in all the transmission intensities. However, our pharmacological model assumed that all the parasites are sensitive to SP and the protective efficacy of malaria infection might be different in the area of transmission with SP resistance parasites. Although the efficacy of clearing malaria infection might be lower due to drug resistance,IPTp-SP still shows a significant benefit in preventing low birth weight[31]. Despite the underlying mechanism of protecting low birth weight being unclear, antibacterial properties of SP might also play an important role in improving the birth weight of the neonates[32].Although alternative strategies are available, SP remains the firstline regimen recommended as IPTp for its long half-life, bene fit on increased birthweight, better compliance being a single dose at each time and cost-effectiveness.

The simulated results show that missing doses during the second trimester results in a higher risk of acquiring a new infection than missing doses in the third trimester. This would imply it is most important to encourage IPTp-SP in the second trimester. However,the simulated results do not consider whether subsequent IPTp doses would be sufficient to clear any new infections acquired when doses are missed. It is also important to consider when the foetus is most vulnerable to placental malaria. For example, foetal growth varies throughout pregnancy and the most rapid growth occurs between weeks 30 to 40. Malaria infections occurring during this phase of rapid growth appear to be associated with a higher risk of delivering low birth weight babies[33]. This suggests that reducing the risk of malaria in the third trimester may be the most important consideration and that even if IPTp-SP is only taken in the third trimester, it may be more bene ficial than it initially appears in Figure 3.

The WHO recommended (in 2013[4]) providing IPTp-SP at every ANC scheduled visit starting from second trimester at least once monthly. The PK/PD model investigated the monthly treatment including up to 6 or 7 doses, based on a clinical trial in Malawi that investigated the efficacy of up to seven IPTp doses during pregnancy[34]. The simulated four and six-weekly IPTp-SP regimens were able to prevent new infections with sensitive parasites in almost all women (>99%) regardless of transmission intensity, provided they fully adhere to the recommendations (Figure 2). However, the efficacy of preventing new infection declined in the eight-weekly regimen at high transmission settings.

Full adherence to the recommended IPTp-SP regimen is clearly crucial to reach the maximal protection during pregnancy. However,across the 36 countries that had adopted IPTp-SP in 2016, only 56% of pregnant women received at least one IPTp-SP dose and only 19% of pregnant women received three or more doses[1]. There are numerous potential reasons for poor uptake and adherence to IPTp regimens with the principal causes suggested to be a limited knowledge of malaria prevention during pregnancy, irregular and late attendance to ANC and drug stock outs[35,36]. Education regarding the risks associated with malaria in pregnancy and alternative approaches to drug delivery, for example via traditional birth attendants and community health workers, also have the potential to improve IPTp uptake and adherence[37].

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no con flict of interest.

Ethical consideration

This study was pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD)modelling about antimalarial drugs in the R programme. In this PK/PD model, IPTp-SP treatment was simulated in 1000 pregnant women for each scenario. These pregnant women were not human patients, they were simulated (generated) in the model. Since the human participants were not included in the study, ethical approval was not applicable to the research project.

Funding

This work was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation(grant No. 37999.01) and the Medical Research Council (grant No. G110052) and supported by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Authors’ contributions

KK and EMH conceived the study. EMH, KK and MNNH wrote the computer code and ran the experiments. EMH, IH, KK and MNNH interpreted the results. MNNH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and EMH, IH and KK contributed to writing the manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2020年8期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2020年8期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Chinese Expert Consensus on Early Prevention and Intervention of Sepsis

- ATP gatekeeper of Plasmodium protein kinase may provide the opportunity to develop selective antimalarial drugs with multiple targets

- Diagnostic performance of C-reactive protein level and its role as a potential biomarker of severe dengue in adults

- Using twitter and web news mining to predict COVID-19 outbreak