Active surveillance in metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors:A 20-year single-institutional experience

He-Li Gao,Wen-Quan Wang,Hua-Xiang Xu,Chun-Tao Wu,Hao Li,Quan-Xing Ni,Xian-Jun Yu,Liang Liu

He-Li Gao,Wen-Quan Wang,Hua-Xiang Xu,Chun-Tao Wu,Hao Li,Quan-Xing Ni,Xian-Jun Yu,Liang Liu,Department of Pancreatic Surgery,Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center,Shanghai 200032,China

He-Li Gao,Wen-Quan Wang,Hua-Xiang Xu,Chun-Tao Wu,Hao Li,Quan-Xing Ni,Xian-Jun Yu,Liang Liu,Department of Oncology,Shanghai Medical College,Fudan University,Shanghai 200032,China

He-Li Gao,Wen-Quan Wang,Hua-Xiang Xu,Chun-Tao Wu,Hao Li,Quan-Xing Ni,Xian-Jun Yu,Liang Liu,Shanghai Pancreatic Cancer Institute,Shanghai 200032,China

He-Li Gao,Wen-Quan Wang,Hua-Xiang Xu,Chun-Tao Wu,Hao Li,Quan-Xing Ni,Xian-Jun Yu,Liang Liu,Pancreatic Cancer Institute,Fudan University,Shanghai 200032,China

Abstract

Key words:Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor;Liver metastasis;Active surveillance;Prognosis;Nomogram

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs),which account for 31.5% of total gastroenteropancreatic NETs,are the most common form of pancreatic tumors in China[1].About one-fourth of PanNET patients have metastasis at diagnosis[2],and the liver is the most common metastatic site.The prognosis of patients with metastatic PanNETs is heterogeneous and varies widely,from 10 mo to more than 10 years.Multiple lines of systemic treatment are considered the standard of care in metastatic nonfunctioning PanNETs (NF-PanNETs),namely,somatostatin analogs,chemotherapy[3],sunitinib,and everolimus[4].However,systemic therapy may not be essential for every patient with metastatic PanNET.To avoid over-treating indolent asymptomatic tumors,the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for PanNETs state that,for locoregional advanced disease and/or distant metastasis,tumor marker analysis and screening every 3-12 mo is an option if the patient is asymptomatic,has low tumor burden,and has stable disease[5].However,specific factors that influenced surveillance were not mentioned.In addition,data regarding the period of active surveillance in patients with metastatic PanNET are lacking.

The benefits of active surveillance have been well established in randomized clinical trials of other metastatic malignancies,such as metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC)[6],melanoma[7,8],and metastatic prostate cancer[9,10].In this study,we retrospectively reviewed the clinicopathological data of patients with liver metastatic NF-PanNETs who received active surveillance in our institution over the past 20 years.Additionally,we established a nomogram to predict the suitable characteristics for active surveillance in liver metastatic NF-PanNET patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

A retrospective review of the NF-PanNET databases of the Pancreatic Oncology Department,Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC) was performed.396 PanNET patients with metastasis were evaluated.All patients had histologically confirmed PanNET between 1998 and 2018.Pathology records of all included patients were reviewed by the Pathology Department at the FUSCC.All patients had asymptomatic NF-PanNET with liver metastasis,and patients without treatment were selected.We did not specify any laboratory parameters or comorbidities for eligibility.This research was approved by the hospital ethics committee,and written consent was provided for patient information to be used for research purposes.The study was approved by the FUSCC ethical committee.

Tumor characteristics

Data were retrieved from patient medical records and included patient demographics(age and sex),pathology reports (T stage,N stage,tumor grade,Ki-67 index,and differentiation),and radiographical documentation [computed tomography (CT),magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS)].The tumor burden of liver metastasis was measured using the AW VolumeShare 5 system,and the axis of the liver metastasis was measured using MRI screening.Tumor grading was in accordance with the 2017 World Health Organization classification[11].Tumor TNM staging was based on the 2006 ENETS TNM staging system for patients with PanNETs[12].

Follow-up and survival

Follow-up was performedviaoutpatient visit or telephone in October 2018.Patients received an enhanced MRI or CT scan every three months.Study investigators assessed progression according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors(RECIST) version 1.1[13].The active surveillance time in the study was defined as the time from the start of surveillance to the initiation of systemic therapy or withdrawal of consent.The time to progression (TTP) during surveillance was defined as the interval between the start of surveillance and disease progression as evaluated by RECIST 1.1.Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time of diagnosis to death from any cause or the date of the last follow-up (censor date).The median follow-up time was calculated based on censored observations.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and proportions.Categorical data were compared by means of the Chi Square-test.Median OS and TTP were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves,with subgroups being compared using the log-rank test.Cox proportional hazard models were performed to identify independent predictors of TTP.Univariate analysis was performed for age,sex,resection of primary tumor,T stage,N stage,the largest axis of the liver metastasis,tumor burden of the liver metastasis.Subsequently,all variables with aPvalue <0.10 were selected for multivariable analysis.Subanalysis was performed to identify predictors of TTP for the different histopathologic subtypes.APvalue <0.05 was considered statistically significant.Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 software (SPSS,Chicago,IL,USA).The nomogram and C-index were calculated using R (version 2.12.2;http://rproject.org).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The study included 76 patients who received active surveillance during the follow-up period.The decision to choose active surveillance in 66 patients was made jointly by the multidisciplinary team,while 10 out 76 patients choose active surveillance because they refused medical treatment due to the financial burden.Patients were initially diagnosed between August 1998 and February 2018.Demographic and baseline characteristics of the 76 included patients are listed in Table 1.Less than half of the patients (40.8%) were diagnosed as stage I-III at the time of surgery,and had recurrent disease during follow-up.In addition,59.2% of patients were diagnosed with stage IV disease.The median disease-free survival was 31 mo (range:6-132 mo).Over half ofthe patients (59.2%) had liver metastasis at the time of diagnosis.All patients had pathological confirmation of liver metastasis by biopsy.All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2 when active surveillance was initiated.

Table 1 Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with liver metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors,n (%)

Outcomes of NF-PanNET patients under surveillance

Patients were followed up for a median 42 mo (range:8-240 mo).The median active surveillance time was 14 mo [95% confidence interval (CI):11.13–16.87].Sixty-nine(90.7%) patients met the criteria for RECIST-defined progressive disease (PD) at some point in the study,and the median TTP (mTTP) during surveillance was 10 mo(95%CI:7.23-12.76).Of the 76 patients,66 started systemic therapy during the followup period.However,10 patients with PD refused treatment due to personal orfinancial problems,and 4 of these patients died as a result of disease progression.The median OS for the 10 untreated patients was not reached (range:10-113 mo).The median OS for the whole cohort was also not reached.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of TTP risk factors

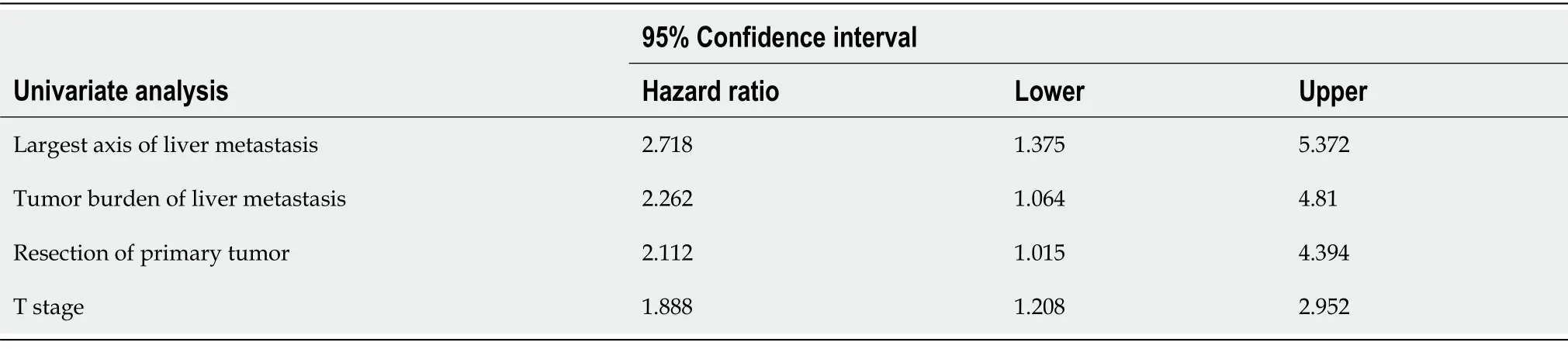

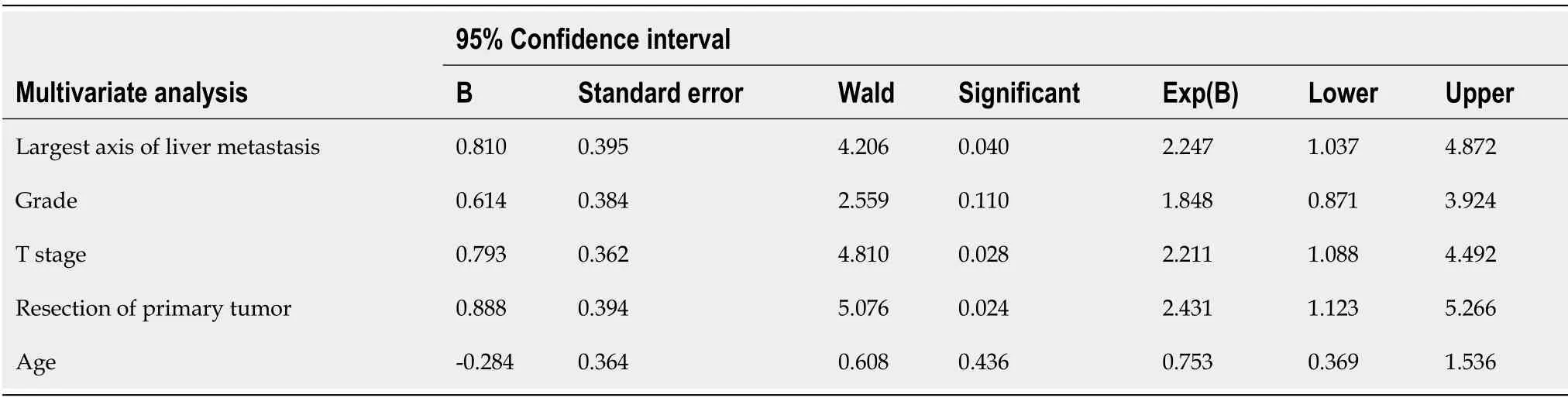

Univariate analysis of baseline prognostic factors revealed that the following risk factors were significantly associated with TTP during surveillance (Figure 1):Resection of the primary tumor (resectedvsnon-resected:10 movs6 mo,P= 0.002),and T stage(T1-2vsT3-4:12 movs6 mo,P= 0.038).Patients with the largest axis of the liver metastasis ≤ 5 mm had longer mTTP than patients with liver metastasis >5 mm (18 movs7 mo,P= 0.002),also those with a tumor burden of the liver metastasis <0.5% had longer mTTP than patients with a tumor burden >0.5% (15 movs7 mo,P= 0.037).When examining the Ki-67 index of the liver metastases,patients with G1 had a longer TTP than those with G2,but the result was not statistically significant (12 movs10 mo,P= 0.165).In the subgroup with liver metastasis,debulking resection of the primary tumor was also significantly correlated with a longer TTP (15 movs6 mo,P= 0.007),whereas debulking resection (transarterial embolization or ablation) of the liver metastasis showed no relationship with TTP (P>0.05).The axis of liver metastasis was measured by MRI screening (Figure 2).

In the multivariate analysis,only the largest axis of the liver metastasis [hazard ratio(HR):2.11,95%CI:1.0-4.44;P= 0.049],resection of the primary tumor (HR:2.11,95%CI:1.01-4.39;P= 0.045),and T stage (HR:2.53,95%CI:1.3-4.93;P= 0.006) were independent prognostic factors (Tables 2 and 3).

Nomogram for TTP risk in metastatic PanNETs

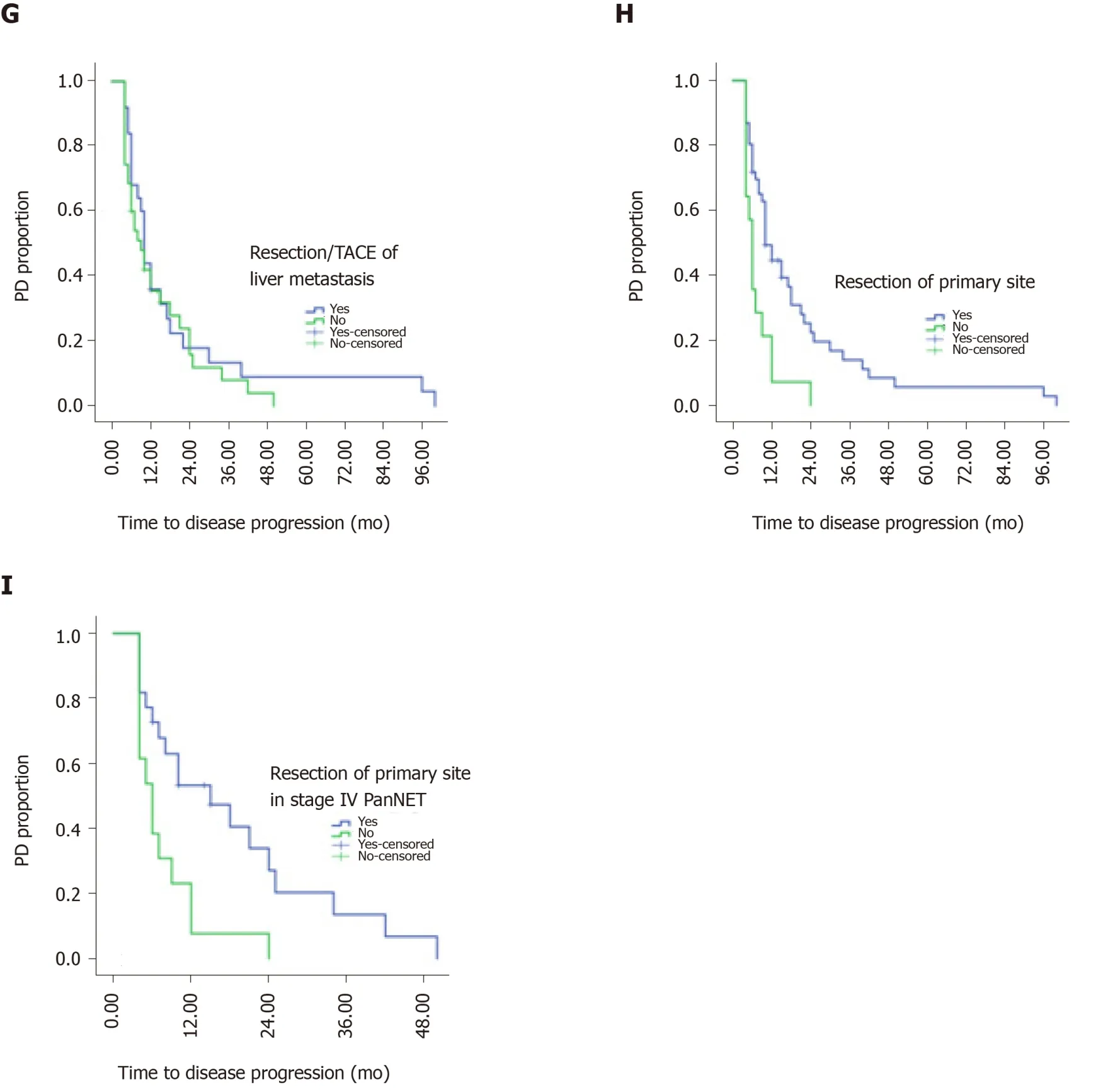

On the basis of the multivariate analysis,we used a recursive partitioning algorithm to separate patients based on the risk factors (largest axis of metastasis >5 mm,T3-T4,and non-resection of the primary tumor) into a favorable group consisting of patients with no risk factors,an intermediate group consisting of patients with one risk factor,and an unfavorable group consisting of patients with two or three risk factors.The favorable group had an estimated mTTP of 25 mo,whereas the intermediate and unfavorable groups had an estimated mTTP of 10 mo and 6 mo,respectively(Figure 3).The difference was significant (HR:2.545,95%CI:1.65-3.92;P<0.001).

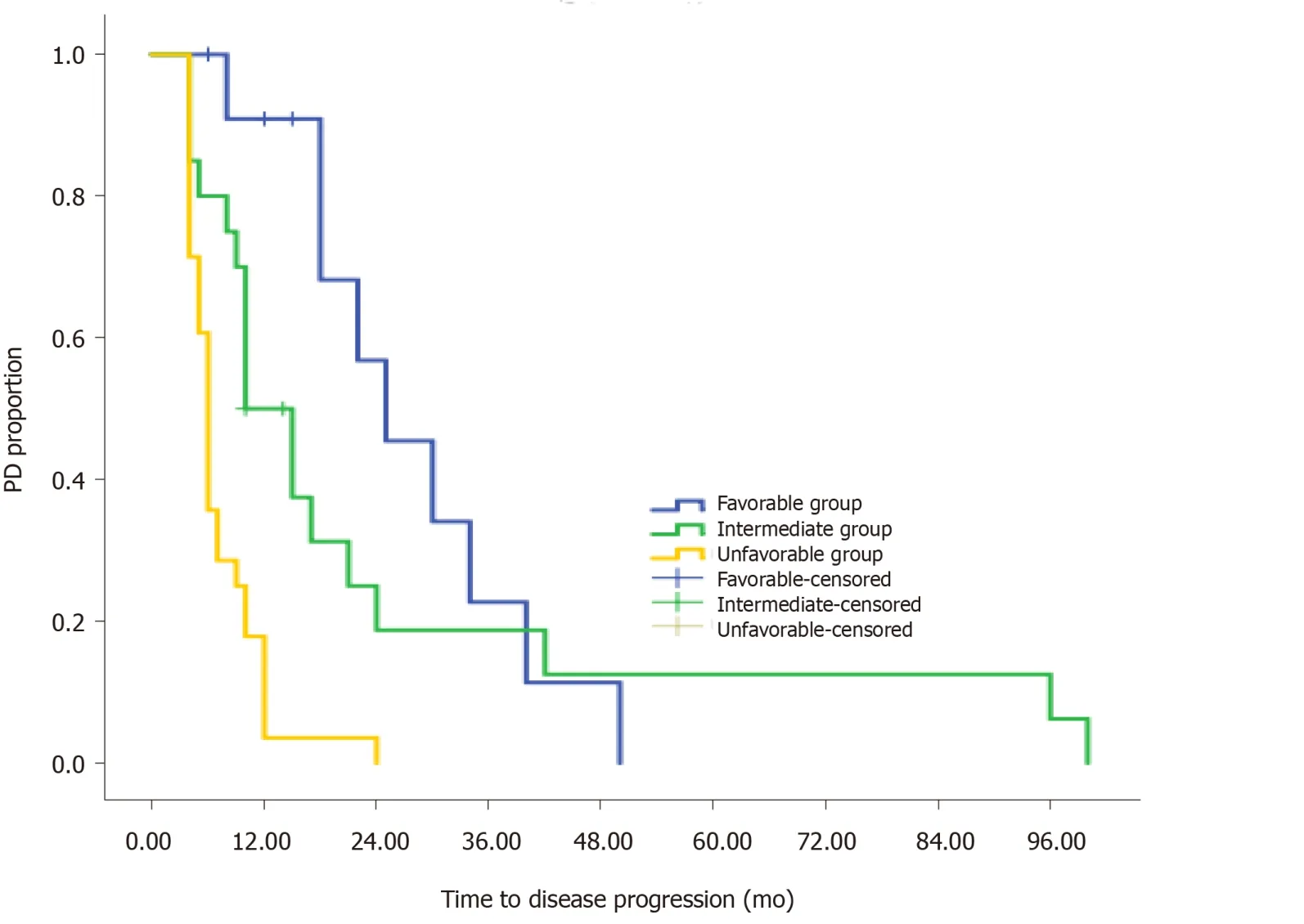

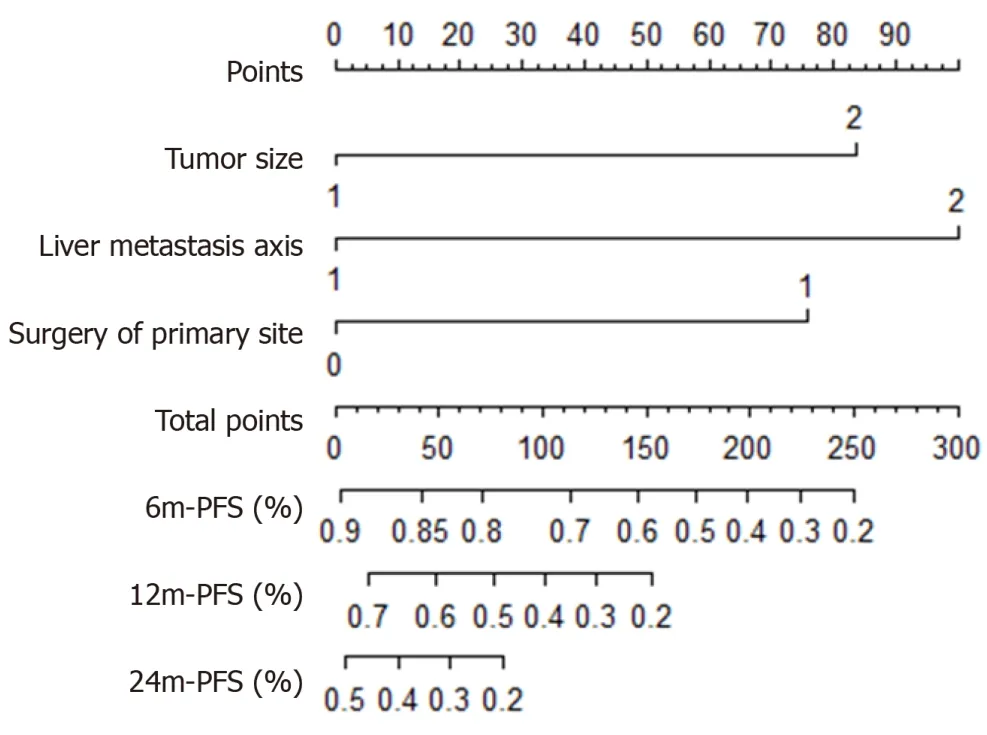

A prognostic nomogram that combined all three independent predictors for TTP during surveillance of metastatic PanNETs is shown in Figure 4.The C-index of the nomogram for predicting TTP was 0.603 (95%CI:0.47-0.74).Moreover,the calibration plot showed good calibration.

DISCUSSION

The findings from our study indicated that active surveillance was a viable strategy in some patients with metastatic NF-PanNETs.The median surveillance period was more than 12 mo,and the mTTP during surveillance was 10 mo.For patients with no risk factors,the mTTP was more than 24 mo.Our multivariate analysis and nomogram also showed that patients with fewer adverse prognostic features should be considered for active surveillance.

Metastatic PanNET is a disease characterized by a varied natural history.Many prognostic schemas have been developed,leading to a 5-year OS rate of more than 60%[14].Stage,grade,and functionality are all independent factors related to the prognosis of PanNETs[15,16],and some gene mutations are also associated with prognosis,such asMEN1,ATRX/DAXX[17],and genes in themTORpathway[18],indicating the diverse underlying biology of metastatic NF-PanNETs.

To our knowledge,very little prospective evaluation has been carried out to study surveillance in metastatic NF-PanNETs.However,active surveillance has been used in cases of neuroendocrine neoplasms in other organs.Almost 50% of patients with asymptomatic metastatic pheochromocytomas (PCs) and paragangliomas (PGLs) had stable disease after a year of follow-up[19].It was concluded that selected PC/PGL patients with slowly progressing tumors could safely use the wait-and-see strategy as an option[20].In cases of medullary thyroid carcinoma,patients with low disease volume should be considered for a wait-and-see strategy;only those with a large volume and PD are clear candidates for systemic therapy[21].Treatment strategies for other indolent malignancies also take an active surveillance approach into account.A prospective phase II trial of 52 patients with RCC showed that a subset of patients with metastatic RCC can safely undergo surveillance before starting systemic therapy.Favorable factors include fewer International Metastatic Database Consortium adverse risk factors and fewer organs affected by metastasis[6].A retrospective series of 58 patients with metastatic RCC noted an initial observation period of 12.4 mo until systemic therapy was started[22].For patients with follicular lymphoma with low tumor burden,a study examining a watch-and-wait strategy indicated a median time to starting therapy of 31.1 mo;46% of patients did not need treatment at 3 years,and there was no difference in OS compared to the treatment group[23].

Table 2 Univariate analysis of risk factors for time to progression in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

Table 3 Multivariate analysis of risk factors for time to progression in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

A surveillance-based approach has been investigated in small NF-PanNETs[24].Surveillance of liver metastatic NF-PanNETs has not been fully evaluated.In the CLARINET trial[25],although 96% of patients had stable disease in the 3 to 6 mo before randomization,mPFS and 24-mo PFS rate were significantly prolonged with lanreotide in comparison with placebo.This result supports that starting SSA therapy before tumor progression may prevent tumor growth.However,our retrospective analysis restaged NF-PanNET patients with liver metastasis and found that,a subset of favorable patients (less 10%) in our cohort,as defined by the largest axis of the liver metastasis <5 mm,T1–T2,and resection of the primary site,showed a TTP of more than 2 years without systemic therapy.This subpopulation may be considered for active surveillance in clinical management,if the patient’s situation allows.Appropriate selection of patients and adequate monitoring are crucial for this approach.In our study,more than 90% patients with risk factors had PD after 6-10 mo,which made them unsuitable for active surveillance and systemic targeted therapy should be started immediately.The exclusion and inclusion criteria in clinical trials may also need to take these factors into account,as patients with favorable factors may have stable disease without any treatment.

Our study has some limitations.First,it was a retrospective study.We did not have another cohort on which to test the nomogram,and the C-index of the nomogram was not very high.Second,patients in the study were not from a highly selected population.Some patients refused systemic therapy due to financial problems.Furthermore,we did not set a control group of patients with treatment.Nevertheless,prospective assessment of this strategy in selected patients would provide guidance for physicians on how to select appropriate patients for active surveillance.

In conclusion,our study showed that active surveillance might be an approach for metastatic NF-PanNET patients with favorable risk factors,while other patients with metastatic NF-PanNET progressed rapidly without treatment.Additional investigations into the risks and benefits of surveillance are warranted.

Figure 1 Determination of the clinicopathological factors predicting time to progression during surveillance of metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.A:Tumor burden of liver metastasis;B:Largest axis of the liver metastasis;C:T stage;D:M stage at diagnosis;E:Grade of liver metastasis;F:Grade of the primary tumor;G:Resection/transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of the liver metastasis;H:Resection of the primary tumor;I:Resection of the primary tumor in patients with stage IV disease.PanNET:Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor;TACE:Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization;PD:Progressive disease.

Figure 3 Risk stratification for predicting time to progression during surveillance on Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.PD:Progressive disease.

Figure 4 Nomogram for predicting time to progression during surveillance of metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors based on our proposed model.Largest axis of the liver metastasis,T stage,and resection of the primary tumor.PFS:Progression-free survival.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) are heterogeneous and indolent;the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines state that delaying treatment is an option for PanNET with distant metastasis,if the patient has stable disease.

Research motivation

The NCCN did not mention specific factors that influenced surveillance.In addition,data regarding the period of active surveillance in patients with metastatic PanNET are lacking.

Research objectives

To describe the factors influencing active surveillance in patients with liver metastatic nonfunctioning PanNETs (NF-PanNETs).

Research methods

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients with liver metastatic NF-PanNETs who received active surveillance were collected,and the median time to disease progression (TTP) was measured.

Research results

The median TTP (mTTP) was 10 mo in 76 patients with liver metastatic NF-PanNETs.Multivariate analysis showed that the largest axis of the liver metastasis >5 mm (P=0.04),non-resection of the primary tumor (P= 0.024),and T3-T4 stage (P= 0.028) were associated with a shorter TTP.The mTTP in patients with no risk factors was 24 mo,which was significantly longer than that in patients with one (10 mo) or more (6 mo)risk factors (P<0.001).A nomogram with three risk factors showed reasonable calibration,with a C-index of 0.603 (95%CI:0.47–0.74).

Research conclusions

Patients with favorable factors had a time to progressive disease of more than two years without systemic treatment;further studies with a larger sample size and a control are required.

Research perspectives

Active surveillance may only be safe for metastatic NF-PanNET patients with favorable risk factors,and other patients progressed rapidly without treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Sheng-Jian Zhang,from the Radiology Department of FUSCC,for CT/MRI imaging support,and Ze-Zhou Wang,from the Cancer Prevent Department of FUSCC,for statistics review.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年17期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年17期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Diagnosis and treatment of an elderly patient with 2019-nCoV pneumonia and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Gansu Province:A case report

- Shear wave elastography may be sensitive and more precise than transient elastography in predicting significant fibrosis

- Diagnosis and treatment of mixed infection of hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis:Four case reports

- Surgical strategy used in multilevel cervical disc replacement and cervical hybrid surgery:Four case reports

- Gallbladder sarcomatoid carcinoma:Seven case reports

- Diagnostic value of ultrasound in the spontaneous rupture of renal angiomyolipoma during pregnancy:A case report