Techniques for overcoming atretic changes of the portal vein in living donor liver transplantation

Jeong-Moo Lee, Kwang-Woong Lee

Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 101 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea

Keywords:

ABSTRACT

Introduction

Obliteration of the hilar structure in the recipient's surgery for liver transplantation (LT) is one of the challenges.In general, severe collateral vessels develop due to portal hypertension in liver transplant candidates.This is the cause of fatal bleeding before surgery,and also the cause of massive bleeding during transplantation.Additionally, transition of long-term portal vein (PV) flow to collateral main can also cause portal vein obliteration.

There are several causes for the obliteration of the PV.Congenital cavernous transformation of the PV is the most common cause in pediatric cases.Atretic changes of the PV sometimes observed in patients with biliary atresia or congenital web formation in the PV are also a cause of PV obliteration.In these cases,small PV branches develop around the hilum for the drainage of the mesenteric vein without the development of a large collateral vessel.These cavernous transformed blood vessels are ineligible for anastomosis due to their thin wall and small size [ 1 , 2 ].

Massive portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is usually observed in adult patients with liver cirrhosis.The pathophysiology of PVT is complex, but it appears to be related to liver cirrhosis, which causes elevation of portal pressure associated with endothelial injury and thrombus formation [3].PVT incidence during LT has been reported to range from 2.1% to 26% [4].Many surgical techniques have been reported for overcoming this situation.In 2009, Sato and colleagues reported four cases of PVT treated using superficial femoral vein graft interposition during living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) [5].

Inflammatory changes of the hilar structure due to recurrent cholangitis and repetitive procedures in primary biliary cirrhosis or biliary atresia and repeated treatments like transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and intra-arterial chemotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)sometimes make it difficult to locate an appropriate anastomosis site [ 6 , 7 ].

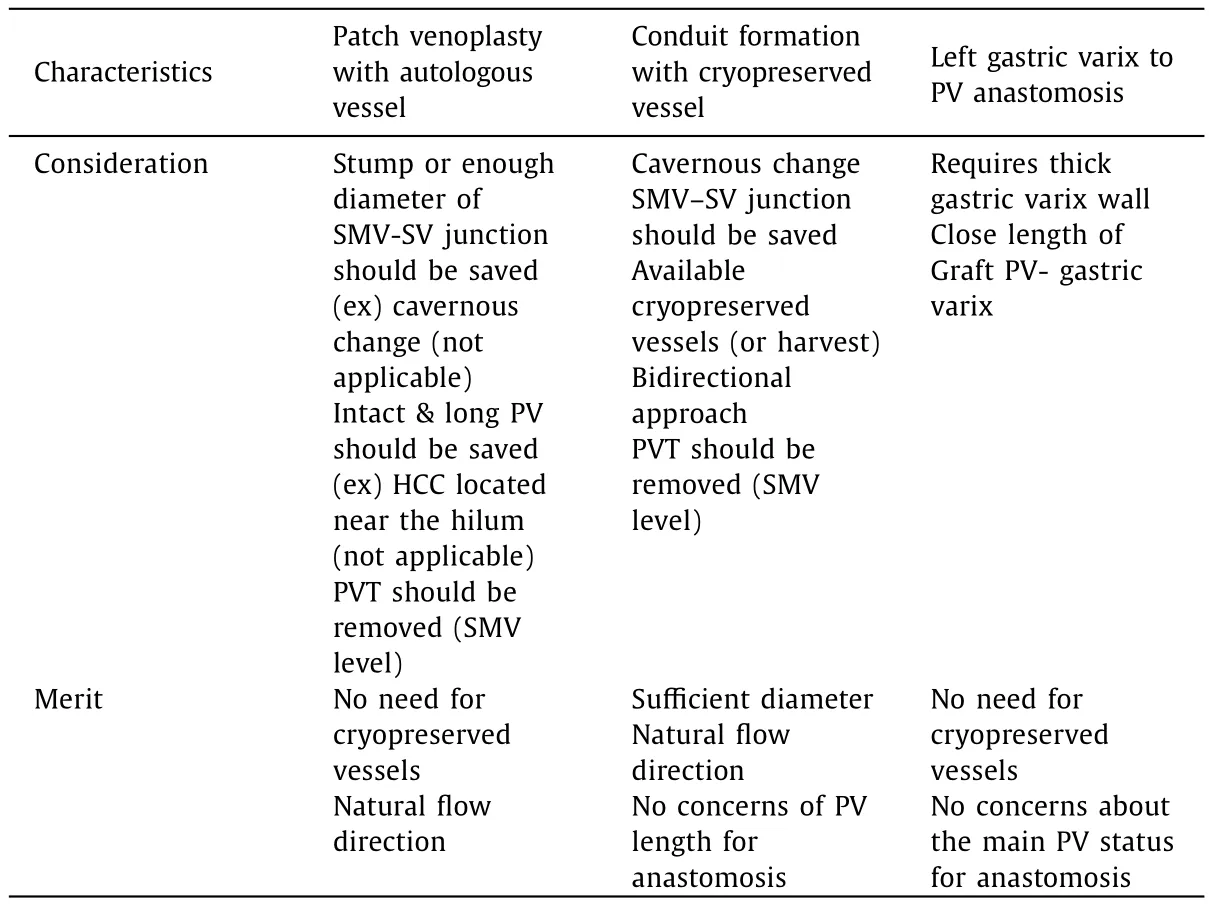

Table 1Considerations and merits of each method of atretic PV anastomosis in liver transplantation.

In case of localized PVT, proper flow can be maintained through thrombectomy, but if the patients had diffuse PVT that extended to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and splenic vein (SV),thrombectomy itself is dangerous, and in some cases, the wall becomes weakened after thrombectomy.As a result, it becomes unsuitable for anastomosis.In particular, if the substitute vein is difficult to harvest, a resolution must be considered.

The purpose of this study was to introduce various alternatives to perform LDLT by conducting PV anastomosis in atretic PV and to review related literature.

Methods

LDLT was performed using different anastomosis techniques in patients who had atrophic changes in the PV.Three typical surgical techniques and procedures were described for PV extrahepatic anastomosis performed at the Seoul National University Hospital from January 2010 to December 2018.This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) and the requirement for informed consent was waived by them.All different congenital (e.g.absent and atretic PV) and acquired (e.g.thrombosis including also Budd-Chiari syndrome) modifications of the splanchnic venous drainage were addressed as well as their solutions in LDLT, and various methods were sorted into categories through a literature review.

Results

We described various PV anastomosis and technical tips in recipients with an atrophic PV in LDLT.Features, indications, merits,and drawbacks of each method were described in Table 1.

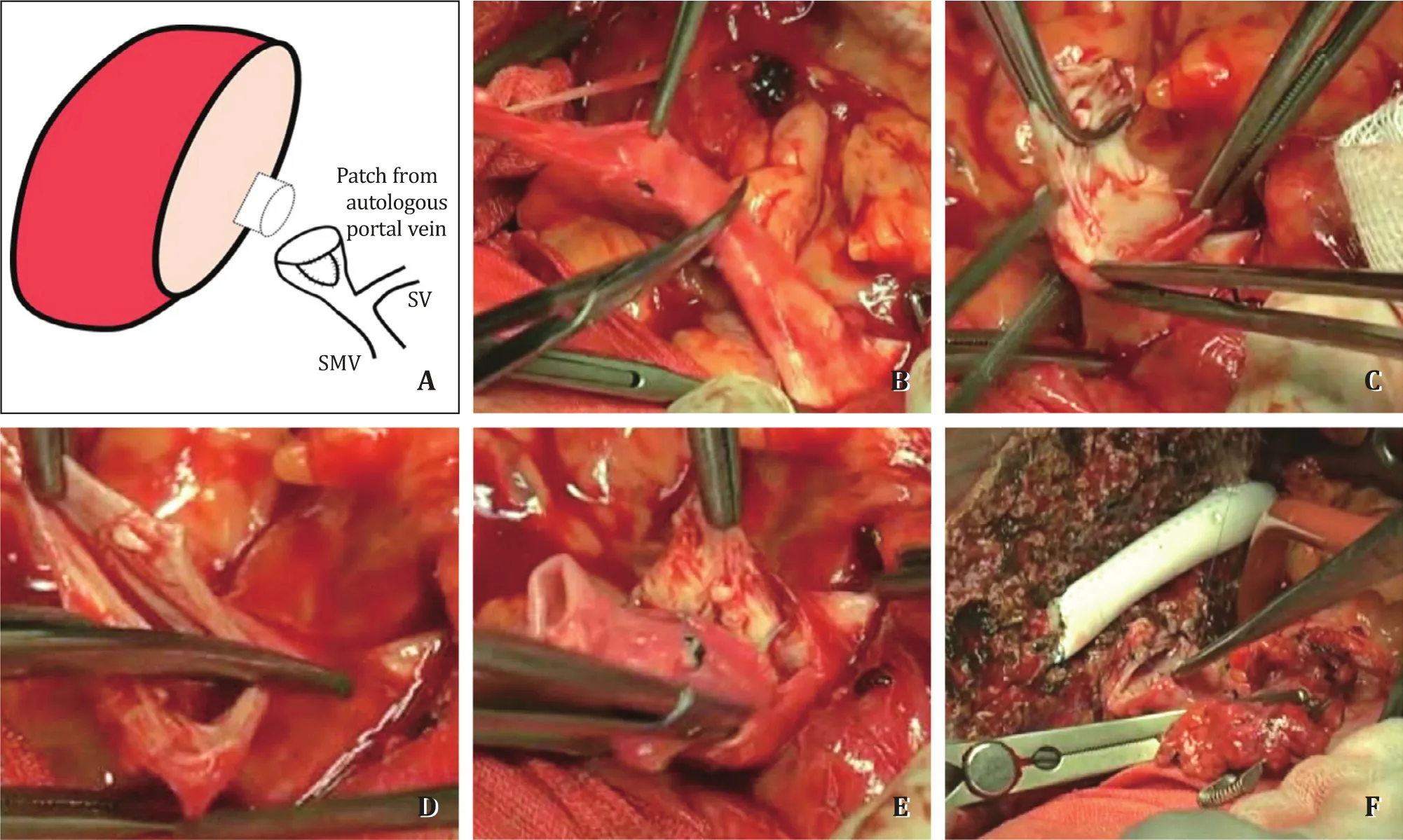

Autologous venoplasty in extensive PVT (Fig. 1)

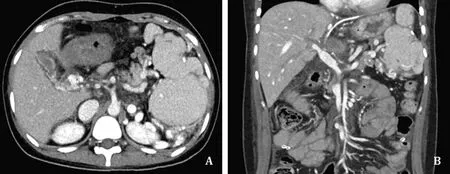

A 49-year-old woman was awaiting a liver transplant due to hepatitis B-related cirrhosis.In the preoperative computed tomography (CT), a large coronary vein connected with an SV near the SMV junction.Additionally, the na?ve PV was obliterated by organized thrombus.PVT was removed by eversion thrombectomy during the operation, but the diameter was still small due to the previous continuous steal of the portal flow.Although the diameter of the PV was small, its length was sufficient and the upper part of the PV was resected for making a vascular patch.The anterior wall of the recipient PV was resected longitudinally to the SMVSV junction.The diameter was widened using the autologous portal patch.PV anastomosis was performed by 6-0 Prolene suture in the usual manner.No automatic stenosis or related complication was noted on CT in 4 months postoperatively.The patient was discharged on postoperative day 15 without any surgical complications (Fig.2).

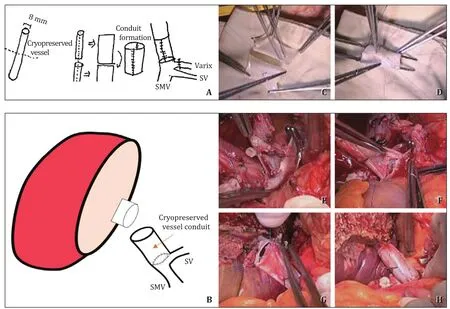

Conduit formation in cavernous transformation of PV (Fig. 3)

A 20-year-old woman had constantly undergone variceal bleeding ligation for PVT of unknown origin.In the preoperative CT,the PV had undergone cavernous transformation, and an extrahepatic collateral for anastomosis could not be found.Even in the intraoperative findings, the main PV was too thin and not suitable for anastomosis.The PV was resected transverse direction at the level of SMV-SV junction such that the lumens were sufficient to perform anastomosis.Only a small-sized cryopreserved vessel was available at the time of operation, thus we made the vessel conduit by using the small-sized cryopreserved vessel.The vessel was longitudinally cut to greatly expand the lumen to make a large cylindrical conduit.Using this as a vascular conduit, we made a new PV from the SMV-SV junction.As the lumen of the recipient side was not sufficient, the SV was slightly incised to preserve enough lumen at the level of the SMV-SV junction.After making the conduit,anastomosis was performed between the graft PV and conduit in the usual manner.After surgery, intact portal flow was confirmed on CT on postoperative day 7.The patient was discharged on 14 days postoperatively without any complications (Fig.4).

Extrahepatic anastomosis using a large left gastric vein (LGV)collateral (Fig. 5)

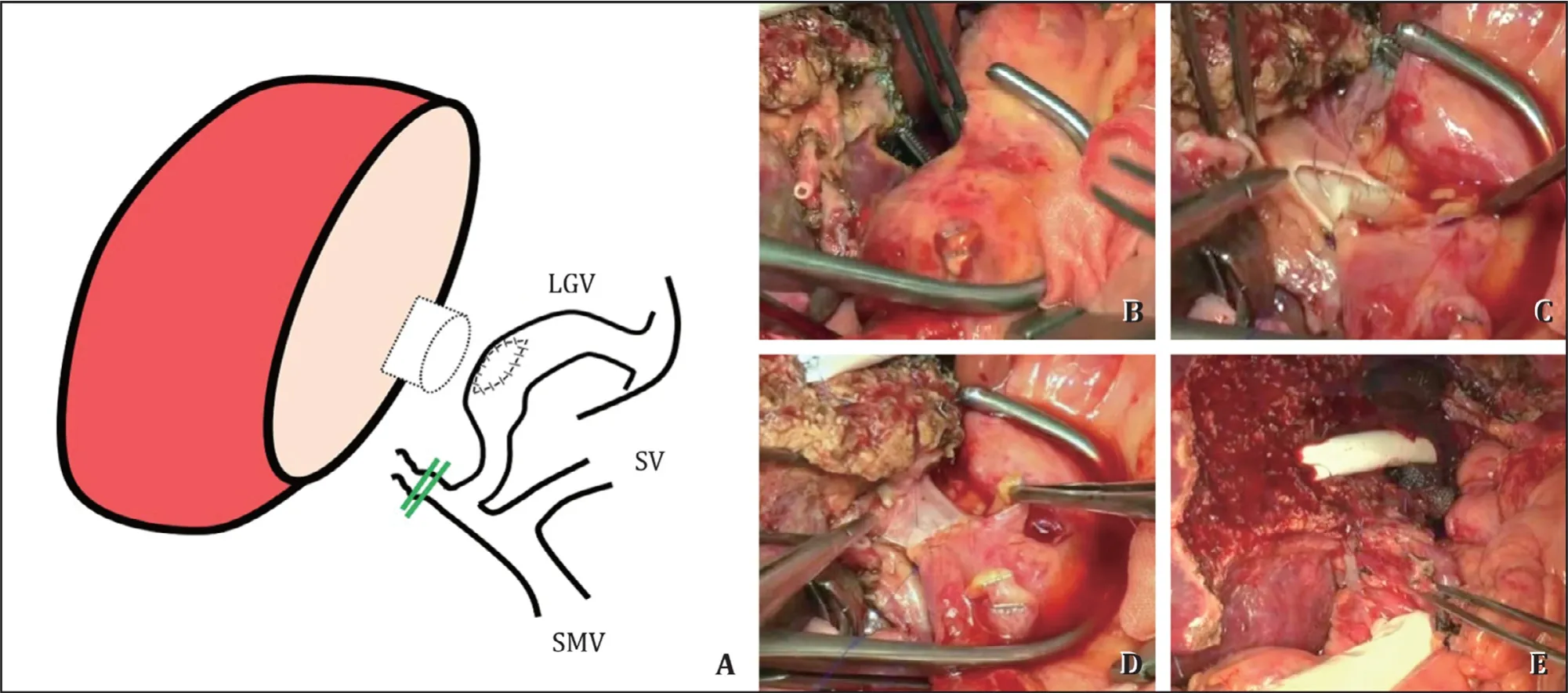

A 52-year-old man presented with hepatitis B-related liver cirrhosis accompanied by PVT with severe calcification.PV thrombectomy was considered rather risky due to the high possibility of SMV injury and massive bleeding.The wall of the LGV, which hadbeen developed for very long time, was sufficiently thick and appropriately located, such that the original PV was ligated.Satinsky clamp was used for the part for anastomosis of the LGV, and after the donor PV and end to side anastomosis, distal varix was tied.After surgery, CT showed that the LGV to PV flow was well maintained and the patient was discharged without related complications (Fig.6).

Fig.1.The procedure of patch venoplasty with autologous vessel.A: Schematic description of the procedure; B: Isolation of portal stump for patch angioplasty; C: Portal vein thrombectomy; D: Making longitudinal incision on the SMV-SV junction to enlarge the atretic na?ve portal vein; E: Patch angioplasty with portal stump; F: Anastomosis of donor portal vein with enlarged recipient portal vein.SMV: superior mesenteric vein; SV: splenic vein.

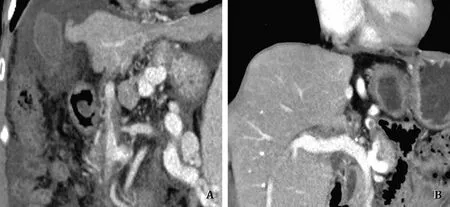

Fig.2.Comparison of preoperative and postoperative computed tomography (CT) findings.A: Preoperative CT finding: obliteration due to extensive portal vein thrombosis;B: Intact portal flow without stenosis at 3 months postoperatively.

Discussion

Several causes of PV obliteration in the recipients prior to LT are known.The solution depends on the cause.Diffuse PVT increases the complexity of LT, but in very severe cases it can also be an indication for multivisceral transplantation [ 8 , 9 ].However,given the organ shortage, it is a complex situation.Therefore, various methods have been introduced to effectively solve this challenge.Hemitransposition is an example of such methods, although the rate of complications is high, and its long-term performance is poor [ 10 , 11 ].LT is one of the best solutions with good long-term outcomes.However, it is difficult to locate the ideal anastomosis point in patients with severe PVT, and various options must be considered according to the patient's condition.In this report, we classified the methods and listed a typical case for each method.

Fig.3.The procedure of conduit formation with cryopreserved vessel.A: A schematic of creating the conduit with cryopreserved vessel; B: A schematic of anastomosis; C:Conduit reconstruction using cryopreserved vessel to enlarge the diameter; D: Sutures with 6-0 Prolene for creating a cylindrical shape with a large diameter; E: Removing the atretic main portal vein at the level of SMV-SV junction; if it requires larger diameter, it is better to extend the incision along with the SV; F: Anastomosis of the SMV-SV junction with the conduit; G: Anastomosis of the conduit with the graft portal vein; H: The final result of the anastomosis using vascular conduit between the donor and recipient portal veins.SMV: superior mesenteric vein; SV: splenic vein.

Fig.4.Comparison of preoperative and postoperative computed tomography (CT) findings.A: Cavernous transformation of portal vein in the hepatic hilum.There were only minor variceal changes around the liver and no large collateral vessel for appropriate extrahepatic anastomosis; B: Intact graft portal flow without stenosis on postoperative day 7.

Category 1. Diffuse PV thrombosis—autologous venoplasty in a case with extensive PVT

The PV is often small in size due to long-term obliteration and large collateral formation.As most of the flow is transitioning from the LGV or splenorenal shunt (SRS) to the varix, the shunts must be ligated to increase the PV flow.The challenge was to widen the PV by performing a longitudinal incision, and expanding its entrance.The advantage of this method was that no cryopreserved vessel or saphenous vein harvest was required, and the caliber could be extended relatively easily.This method is suitable when a gastric varix or SRS is present, but the wall of that collateral is thin such that it cannot be anastomosed.For this method, first, the malignant lesion should not be too close to the hilum, otherwise it is difficult to secure a PV of sufficient length from the recipient.Second, even when the diameter of the PV is small, its length must be sufficiently secured for venoplasty using an autologous PV stump.Third, PV thrombectomy should be safe to perform at theSMV level, because the SMV-SV flow should be sufficiently maintained after venoplasty.

Fig.5.The procedure of extrahepatic anastomosis using a large collateral vessel (left gastric vein).A: A schematic of the anastomosis; B: Large left gastric vein (LGV)collateral; C : After checking the wall thickness and quality, we initiated the anastomosis between the graft portal vein and LGV using 6-0 Prolene sutures; D: The anastomosis was completed and reperfusion was established; E: The final result of the anastomosis using LGV as an alternative approach for mesenteric vein drainage.SMV: superior mesenteric vein; SV: splenic vein.

Fig.6.Comparison of preoperative and postoperative computed tomography (CT) findings.A: Preoperative CT: Diffuse portal vein thrombosis with calcification around SMV level; B: Intact graft portal flow without anastomotic stenosis on postoperative day 7.

Category 2. Congenital cavernous change of PV—conduit formation in a case with cavernous transformation of the PV

In the case of congenital causes such as PVT or web formation of unknown origin, cavernous transformations are often observed in the form of small nets [ 1 , 2 , 12 ].In the preoperative image, several small vessels were visible, but the wall was thin and small, so it was not suitable for anastomosis.The main PV itself was almost in the form of a band, and is often patented up to the SMV-SV junction.However, this does not imply that the collateral has developed around the other side, but because it rises like a spider's web near the hilum, immense bleeding can occur when the hilum is detached, and hepatic artery and bile ducts are also difficult to isolate.

As only small vessels that are not suited for venoplasty using their PV exist around the main PV, it is inevitable to harvest other vessels to make a conduit.Cryopreserved vessels are also used.The great saphenous vein is often harvested, and if only a small-sized cryopreserved vessel is available, as in our case, the great saphenous vein can also be used after reconstruction to match the diameter of the donor graft.

If the sidewall of the SV is further expanded, a main PV stump of sufficient length can be secured, and anastomosis can be performed using a conduit of sufficient size.However, if the vessel is difficult to obtain or there is a complete obliteration up to the SMV level, it is difficult to create a conduit, and harvesting saphenous vein may be necessary.

Some reports have addressed the anastomosis between the mismatched atretic recipient PV and adult normal PV in pediatric case [1 , 2 , 12].It is possible to adjust the PV diameter by cutting the axis of the length and anastomosis is sufficient even when a small PV is used.However, if the recipient's PV is too weak to do anastomosis, a cryopreserved vessel can be a promising solution.

If the PVT extends beyond the SMV-SV junction, thrombectomy with a bidirectional approach can be attempted [13].After maximum PVT removal through the PV stump, SMV can be approached along the gastrocolic trunk.PV thrombectomy can be performed at the level of the SMV after the isolation of the SMV and SV.After making a longitudinal incision to the SMV thrombectomy should be performed in both directions.Finally, PV flow is checked after clearing all PVT, and we can then make the conduit and perform anastomosis.

The limitation of this method is the requirement for a cryopreserved vessel or saphenous vein.This method is not suitable for PVT patients with severe calcification or SMV-SV junction deformity.

Category 3. Absence of suitable PV for anastomosis—Extrahepatic anastomosis using a large collateral

LGV

Long-term portal flow transition to the varix makes the collateral vein more developed.The LGV is the best area for varix to grow and can be used for anastomosis if the thickness is adequate.This is a favorable method when the PVT has prolonged for a long time and is accompanied by calcification.Because it is extensively bonded to the wall and is not suited for anastomosis because of the thin wall after PV thrombectomy or risk of mass bleeding due to damage.Varix is parallel to the direction and the hilum of anastomosis, which can create natural anastomosis.The LGV must be thick enough when using the right liver, and the position is physiologic and does not require vein from other sources.

Safwan et al.have reported a case of PV anastomosis using LGV.Like our case, there was a risk of bleeding with thrombosis accompanied by calcification of the SMV.They implemented the proper LGV and emphasized some principles [14].First, the quality of the product should be tested, and the donor PV must be sufficiently long.Particularly, in the case of LDLT, as it is a little farther than the existing anastomosis position, if the length is not enough, a bridge-type vessel may be required between the donor and recipient veins, but a risk of twist must be considered.

This method has the advantage of performing the anastomosis similar to the original flow direction compared with the other extrahepatic anastomosis methods.Additionally, as it is attached to the end-side, the donor PV and size can be matched regardless of the diameter of the collateral, and the anastomosis can be performed without any size discrepancy.

As a limitation and precaution, a small length of the donor PV should be secured, and after anastomosis, the artery or bile duct anastomosis should be shortened to prevent complications from twist.

Reno-portalanastomosis(RPA)

There are only several cases of RPA in SNUH and therefore, the knowledge on RPA in this article is based on the literature.Along with cavoportal hemitransposition (CPHT), RPA has been reported in several case series with respect to the methods of extrahepatic anastomosis [ 8 , 11 , 15 ].The first premise is to confirm the occurrence of the SRS.Although the location is not clear, RPA may not solve the problem as the mesenteric vein cannot be drained effectively [15-18].In children, the left renal vein is also cut and attached directly [ 18 , 19 ].However, if the anastomosis is excessively tensioned, the PV is pulled by the weight of the kidney which results in bleeding and PV stenosis.To prevent this, artificial blood vessels or autologous blood vessels are used.

This method is suitable in cases with extensive PVT combined with severe calcification.It is also appropriate when the SRS is difficult to be isolated.Because the collateral of the SRS has developed, massive bleeding may occur during isolation.According to Lee's report, a jump graft via an artificial vessel is an appropriate approach [19].However, that method also has a risk of being pushed by other organs such as the small or large intestines because of the long driving course of an interposition graft.

Anothercolicveinanastomosis

In addition to the mentioned anastomosis using the collateral, a method of directly draining the right gastroepiploic vein(RGEV) [20], right colic vein (RCV) [3], and middle colic vein(MCV) [21], which are individual vessels joining the gastrocolic trunk, has also been reported.This method is useful when the SMV is blocked by PVT.As the distance from the donor PV is long, it is difficult to connect directly to the vein of the graft.In this situation we need the cryopreserved vessel or an artificial graft.In the reported paper, either the iliac vein was used [3].

The advantage is that anastomosis can be performed using natural vein and the severities of PVT and PV atrophy are not important.However, as a precaution, well-developed mesenteric vein must be selected that can drain many parts of the blood suffi-ciently.Like RPA, compression or twitch of the jump graft vessel must be carefully avoided.

Literaturereviewandsummary

Previous reports on PV anastomosis have been mainly focused on diffuse PVT.Moreover, the majority of the studies are on the implementation of PVT and cases for extrahepatic pathways such as CPHT and RPA.However, as mentioned earlier, a slightly modified approach is required in children who have congenital atretic changes due to different mechanisms or in case of inflammatory changes surrounding the hilum due to prior treatment for malignancy or recurrent cholangitis.According to a systematic review,ascites, renal dysfunction, and variceal bleeding were the main postoperative complications after CPHT or RPA.The overall mortality was 26% after either CPHT or RPA [15].

With respect to the three methods described, it would be appropriate to choose a method suitable for each situation, maintain the native pathway as much as possible, and prefer to use the collateral where the location is sufficiently close, such as the LGV.However, if none of those can be implemented, jump graft, CPHT,or RPA may be considered [ 13 , 15 , 22 ].Therefore, less invasive is the first choice, slightly more and further more invasive approaches are the alternatives based on the patho-anatomy of the hilum.The goal is to improve the long-term outcomes.

We reviewed several ways to solve the problems caused by the atretic PV in LT.The patient's status usually varies considerably depending on portal hypertension and cirrhosis.Herein, we have classified the various cases into multiple categories and described the solution to select and use the appropriate method based on the clinical situation.Recently, as well as congenital change, the number of patients with an atretic PV due to recurrent treatment of HCC before transplant has been increasing because of treatment modalities such as transarterial radioembolization, stereotactic body radiation therapy, and intra-arterial chemotherapy [ 6 , 7 ].Obliteration of hilar structures is often caused by these iatrogenic interventions, and the number of these patients will be increased in the future.Given the available resources, such as cryopreserved vessels and artificial graft vessels, it is essential to choose the appropriate method corresponding to the situation.Transplant centers, where vessels are relatively difficult to obtain, should find an alternative way.The second case described how to make the vessel available through reconstruction even if it was not suitable for anastomosis.According to previous studies, patency increases when the peritoneal tissue is fixed and used for vascular reconstruction [ 23-25 ].If we are aware of these various methods, we can proceed the transplantation safely.The limitation of this study is that we are not experienced in RPA and middle colic anastomosis, we just summarized the literature.

In conclusion, the atretic PV is a complex problem to solve in LT.However, if we choose the appropriate surgical method according to each situation, the operation can be safely performed.These methods we described above can be a good reference for a young transplant surgeon to handle such complex situations.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jeong-Moo Lee:Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology,Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Kwang-Woong Lee:Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) and the requirement for informed consent was waived by them.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2020年4期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2020年4期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Small-for-size syndrome in liver transplantation: Definition,pathophysiology and management

- Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation with or without sphincterotomy for large bile duct stones removal: Short-term and long-tem outcomes

- Recent evolution of living donor liver transplantation at Kyoto University: How to achieve a one-year overall survival rate of 99%?

- Optimizing biliary outcomes in living donor liver transplantation:Evolution towards standardization in a high-volume center

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Hepatic artery reconstruction in pediatric liver transplantation:Experience from a single group