Application of Lightning Data Assimilation to Numerical Forecast of Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013)

Rong ZHANG, Wenjuan ZHANG, Yijun ZHANG, Jianing FENG, and Liangtao XU

1 State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, China Meteorological Administration (CMA),Beijing 100081 2 Key Laboratory for Cloud Physics of CMA, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, CMA, Beijing 100081 3 Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences & Institute of Atmospheric Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai 200438

ABSTRACT Previous observations from World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN) and satellites have shown that typhoon-related lightning data have a potential to improve the forecast of typhoon intensity.The current study was aimed at investigating whether assimilating TC lightning data in numerical models can play such a role.For the case of Super Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the lightning data assimilation (LDA) was realized in the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model, and the impact of LDA on numerical prediction of Haiyan’s intensity was evaluated.Lightning data from WWLLN were used to adjust the model’s relative humidity (RH) based on the method developed by Dixon et al.(2016).The adjusted RH was output as a pseudo sounding observation, which was then assimilated into the WRF system by using the three-dimensional variational (3DVAR) method in the cycling mode at 1-h intervals.Sensitivity experiments showed that, for Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013), which was characterized by a high proportion of the inner-core (within 100 km from the typhoon center) lightning, assimilation of the inner-core lightning data significantly improved its intensity forecast, while assimilation of the lightning data in the rainbands(100–500 km from the typhoon center) led to no obvious improvement.The improvement became more evident with the increase in LDA cycles, and at least three or four LDA cycles were needed to achieve obvious intensity forecast improvement.Overall, the improvement in the intensity forecast by assimilation of the inner-core lightning data could be maintained for about 48 h.However, it should be noted that the LDA method in this study may have a negative effect when the simulated typhoon is stronger than the observed, since the LDA method cannot suppress the spurious convection.

Key words: lightning, three-dimensional variational (3DVAR) data assimilation, Typhoon Haiyan, typhoon intensity

1.Introduction

Typhoons are one of the major types of disastrous weather systems in China, which often bring about severe weather such as strong winds, heavy rainfall, large waves, and storm surges to the area along or close to its track.The Northwest Pacific Ocean is the most typhoonprone area in the world.On average, 27 typhoons occur each year in this region, and about one third of them make landfall in China (Li et al., 2004), causing serious damage to coastal areas of China.In the past few decades, owing to the progress in observation technologies,application of data assimilation, and improvement in numerical prediction models (finer horizontal and vertical resolutions as well as improved physical parameterizations), the prediction of typhoon tracks has made remarkable progress; yet, the prediction of typhoon intensity has shown little improvement (Duan et al., 2005; DeMaria et al., 2014).

Typhoon Intensity forecasts are not only related to large-scale environmental factors such as the sea surface temperature (SST), air humidity, and lower tropospheric wind shear, but also involved with the convective-scale processes within the typhoon inner-core area (Hendricks,2012; Jiang and Ramirez, 2013).One of the important reasons for the inadequacy of typhoon intensity forecasts is the lack of observational data in open ocean areas, especially in the typhoon inner-core region.Although airborne radars (Rogers et al., 2013), airborne dropsondes(Wu et al., 2005), airborne in-situ probes (Jorgensen,1984), and rocket dropsondes (Lei et al., 2017) have been used recently to observe the internal structure of several typhoons, their observation time and scope are very limited and no continuous observations can be provided.Geostationary satellites can measure the visible and infrared radiation, but clouds generally prevent such measurements below the cloud top near the typhoon center(DeMaria et al., 2012).Both the low-orbiting passive and active satellites are able to provide data below the cloud top, but they usually scan one area only twice per day at lower latitudes (Asano et al., 2008).Thus, typhoon forecast models currently have incomplete information available for data assimilation and initialization.

With the construction of lightning location networks and application of satellite lightning observation data, the lightning activity in typhoons has attracted much more attention in recent years.Knowledge of the lightning activity in typhoons originated from studies on hurricanes over the Atlantic Ocean.By superimposing National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN) data on the infrared satellite image, Molinari et al.(1994) found that the lightning flashes of Hurricane Andrew (1992) were mainly located in the eyewall and outer rainbands, and eyewall lightning tended to occur almost exclusively prior to and during periods of intensification of the storm.Molinari et al.(1999) further analyzed the lightning flashes during nine hurricanes in the Atlantic basin and found a clear three-circle distribution of the flash density: a weak maximum in the eyewall region, a clear minimum 80–100 km outside the eyewall, and a strong maximum in the vicinity of outer rainbands (210–290-km radius).With the availability of World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN) data, characteristics of the lightning activity of typhoons over the Pacific have also been studied in recent years.Pan et al.(2010) analyzed the spatial and temporal characteristics of lightning flashes of seven typhoons over the Northwest Pacific from 2005 to 2008,and the results showed that there were three distinct lightning flash regions in mature typhoons: a significant maximum in the eyewall regions (20–80 km from the center), a minimum 80–200 km outside the eyewall, and a strong maximum in the outer rainbands (beyond 200 km from the center).Moreover, it was found that eyewall lightning outbreaks usually occurred several hours before the typhoon reached its maximum intensity, which indicated the possibility that the lightning activity could be used as a proxy for intensification of super typhoons.Zhang et al.(2015) analyzed the lightning activities of typhoons over the Northwest Pacific from 2005 to 2009 and investigated the relationship between the inner-core lightning and typhoon intensity changes.They found that the lightning activity in the inner-core (0–100 km) area of typhoons can be a better indicator for prediction of their rapid intensification than that in the outer rainbands.Wang F.et al.(2017) analyzed the lightning activities of 228 typhoons over the Northwest Pacific from 2005 to 2014 and further confirmed the three-circle distribution of the flash density as well as the strong correlation between the inner-core lightning activity and typhoon intensity.Overall, previous studies on lightning associated with typhoons show that: (1) there are frequent lightning activities in the inner-core and outer rainbands, but little in the inner rainbands; and (2) the lightning activity within the inner core, rather than in the outer rainbands, can be a better indicator of typhoon intensity.Besides, these results imply that there is a potential value in assimilating lightning data into numerical models to improve typhoon intensity forecast.

Based on the basic concept that lightning has a tendency to occur in the convection zone with strong updrafts, it is widely recognized that lightning is a valuable proxy for identifying the occurrence of strong convection (Schultz et al., 2011; Rudlosky and Fuelberg, 2013;Giannaros et al., 2016).Previous studies have attempted to assimilate lightning data into numerical weather predication models with different methods (Chang et al.,2001; Papadopoulos et al., 2005; Mansell et al., 2007;Fierro et al., 2012; Mansell, 2014; Marchand and Fuelberg, 2014; Qie et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2016; Dixon et al., 2016; Fierro et al., 2016; Wang H.L.et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017;Wang et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019), revealing significant improvement both in the initial conditions and subsequent forecasts.Zhang et al.(2017) and Qie and Zhang(2019) have provided details on these studies.However,it should be noted that most of these studies focused on small-scale convective systems over land, with relatively little work conducted to assimilate lightning data of typhoons to aid the prediction of their intensity during their development over oceanic areas.Pessi and Businger (2009) nudged the model’s latent heating rates based on the lightning-estimated rainfall in a winter storm over the North Pacific Ocean, and their results showed that the pressure and wind forecasts were generally improved.Fierro and Reisner (2011) used lightning data to saturate the model’s water vapor in the height range from 3 to 11 km to initialize the simulation of Hurricane Rita (2005).In the present study, we try to assimilate the lightning data obtained during Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013) into the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model by using a method that is conceptually similar to that of Fierro et al.(2011), and the typhoon intensity forecasts with and without lightning data assimilation (LDA) were compared and analyzed.Through sensitivity experiments, we aim to answer the following questions: (1)Can the lightning data in typhoons be assimilated into numerical models to improve the accuracy of typhoon intensity forecast? (2) In the process of LDA, how do we select the spatial range of lightning data to achieve the best forecast improvement? The results of this study will not only promote the application of lightning data in typhoon forecast models, but also provide a research basis for methods and techniques involved in the assimilation of typhoon lightning data.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.Section 2 introduces the data used in this study.In Section 3, Super Typhoon Haiyan and its lightning activities are analyzed.In Section 4, the assimilation method and model setup are described.The results are analyzed in Section 5, and summary and discussion are provided in Section 6.

2.Data

2.1 Typhoon data

Super Typhoon Haiyan occurred in November 2013.It is one of the most powerful typhoons ever recorded in Northwest Pacific.Haiyan made landfall and caused catastrophic consequences in the Philippines.Previous studies have shown that Haiyan moved generally westwards across the Pacific with no obvious deflection, and whilst the model-predicted track is relatively accurate,the predicted intensity is much weaker than reality (Chen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014).We chose this typhoon as an example to try to assimilate the lightning data into the WRF model, with a focus on the post-assimilation improvement in its intensity prediction.The best-track data used in this study were from Shanghai Typhoon Institute of the China Meteorological Administration, with the position and intensity of typhoon centers available at 6-h intervals.To match the 1-h cycling LDA frequency,the tracks and intensity of the best-track data at 6-h intervals were linearly interpolated into hourly data.

2.2 Lightning data

The lightning data used in this study were from WWLLN (http://www.wwlln.com), operated by the University of Washington.To date, the network consists of more than 70 stations worldwide.WWLLN locates lightning in real time by using the time of group arrival(TOGA) of the very-low-frequency (VLF; 3–30 kHz)electromagnetic radiation signals produced by a lightning stroke (Jacobson et al., 2006).The time at which the VLF signal arrives at each station is obtained accurately via a GPS clock.Each station processes the measured electric field waveform and sends the arrival time to the central station in real time.When at least five stations in the network detect the same VLF signal, the lightning is located and the time, longitude, as well as latitude are given.WWLLN is able to detect both the cloud-toground (CG) and intracloud (IC) lightning.Because the detection efficiency increases with the peak current of lightning, WWLLN is more efficient at detecting CG lightning since CG lightning tends to have larger peak currents than IC lightning (Lay et al., 2004).The detection efficiency of WWLLN is approximately 10%, with location errors of less than 10 km based on evaluations using observations from short-range lightning location networks as ground truth (Abarca et al., 2010; Abreu et al., 2010).Although its detection efficiency is modest,WWLLN can successfully capture patterns of lightning strikes in typhoons when compared with regional lightning location networks with much higher detection efficiencies (Abarca et al., 2011; DeMaria et al., 2012).

In this study, lightning within a radius of 500 km from the typhoon center was defined as typhoon lightning.Lightning within a radius of 100 km from the center was defined as the inner-core lightning, and lightning within an annular region between 100 and 500 km from the center was defined as rainband lightning.These radial thresholds were purposefully chosen to be consistent with previous studies on typhoon lightning (Zhang et al.,2015; Xu et al., 2017; Fierro et al., 2018; Zhang et al.,2019).

2.3 Satellite data

The brightness temperature (TBB) data used in this study were from theMultifunction Transport Satellite-1R(MTSAT-1R), provided by Kochi University of Japan.MTSAT-1Ris a geostationary satellite and it was launched on 26 February 2005.It has a five-channel imager, including one visible and four infrared channels.Data from the IR1 (10.3–11.3 μm) channel were used in this study.The data covered the region of 20°S–70°N,70°–160°E, with a 0.05° × 0.05° spatial resolution and a 1-h temporal resolution.

3.Super Typhoon Haiyan and its lightning activities

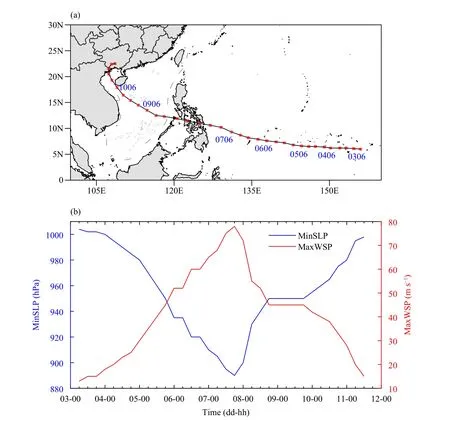

Super Typhoon Haiyan developed from a tropical depression over the ocean to the east of the Philippines during the afternoon of 3 November 2013, and then tracked generally westwards.With favorable environmental conditions, it developed into a severe typhoon on 6 November.Development continued throughout 6 and 7 November, when the enhanced upper-level divergence helped the storm to further strengthen into a super typhoon.Owing to the maintenance of favorable atmospheric conditions and high SST right up to the Philippine coast, the storm made landfall in the central Philippines at its maximum intensity on 8 November, with a maximum 2-min sustained wind speed of 78 m s-1and minimum central pressure of 890 hPa (CMA, 2015), making it the most powerful typhoon landfalling in the Northwest Pacific Ocean to date (Mori et al., 2014).According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council(NDRRMC, 2014), Haiyan caused catastrophic damage to the Philippines, with 6268 fatalities, 28,689 individuals injured, and 1061 missing.After passing through the Philippines, Haiyan quickly weakened to a severe typhoon and turned northwestward.Its intensity was further reduced to the typhoon strength on 10 November.After that, it wiped through the southwestern Hainan Province and entered the Beibu Gulf.Haiyan finally landed in Guangxi Region and then disappeared.Figure 1 shows the evolution of the best track, central maximum wind speed, and minimum sea level pressure during the life cycle of Haiyan.

Fig.1.(a) The best track and (b) minimum sea level pressure (MinSLP) and maximum wind speed (MaxWSP) during the life cycle of Super Typhoon Haiyan.

Figure 2 shows the hourly lightning flash rates of the inner-core and rainband lightning during the life cycle of Haiyan.It can be seen that vigorous lightning activities occurred in the inner-core region.The ratio of inner-core lightning to total typhoon lightning reached as high as 49%.Such a high ratio is contrary to previous studies using regional lightning location networks that primarily captured CG lightning, which found that more lightning occurred in the rainband region than in the inner-core region (Molinari et al., 1994, 1999).Zhang et al.(2019)found that the lightning density (lightning flashes per unit area and time) within Haiyan’s inner core was much higher than that in its rainbands.As suggested by Pan et al.(2014), it may be a common characteristic for a super typhoon that frequent lightning occurs in the inner-core area.A detailed analysis of characteristics of the lightning activity of Haiyan can be found in Wang et al.(2016) and Zhang et al.(2019).

Fig.2.Time series of the hourly lightning flash rates within the rainbands (blue) and inner core (red) of Super Typhoon Haiyan.

4.Assimilation method and model setup

4.1 Assimilation method

Since lightning quantity is not a regular variable in most numerical weather prediction models, lightning observations cannot be directly used for model initialization.It is necessary to convert lightning data to model variables or other related diagnostic variables by using empirical or semi-empirical relations before the LDA.The relationship among the lightning flash rate, water vapor, and graupel mixing ratio established by Fierro et al.(2012) has been utilized in many convective events studies and shown promising results (Fierro et al., 2014,2015; Lynn et al., 2015; Lynn, 2017; Zhang et al., 2017);however, the adjustment magnitude of humidity in this relationship depends heavily on the lightning flash rate.Considering the relatively low lightning detection efficiency of WWLLN (about 10%), the flash rate is less reliable or insignificant in providing information about the strength of convection.Therefore, a simplified method with the adjustment of humidity independent of the lightning flash rate, which was developed by Dixon et al.(2016), was used in this study.For the grids where lightning occurred, the relative humidity (RH) values at all levels in the troposphere (levels where atmospheric pressure exceeded 200 hPa) were adjusted to 90% if the simulated RH values were below 85%.This method does not restrict the adjustment of humidity to any specific vertical layer of the troposphere; rather, it enhances both the surface-based and elevated convection by adjusting RH at all vertical levels within the troposphere.

The basic rationale of this method is based on the concept that lightning can be used to indicate deep moist convection.When lightning occurs, if the necessary RH condition of deep moist convection (in this study, RH≥85%) in the troposphere is not satisfied, the RH value is adjusted to 90%, ensuring that the RH value at positions where the lightning happens is no less than 90%.The increased RH will stimulate the processes of condensation and freezing, thus increasing the release of latent heat and accelerating the cloud updraft, and eventually lead to the production of convection in areas where lightning occurs.

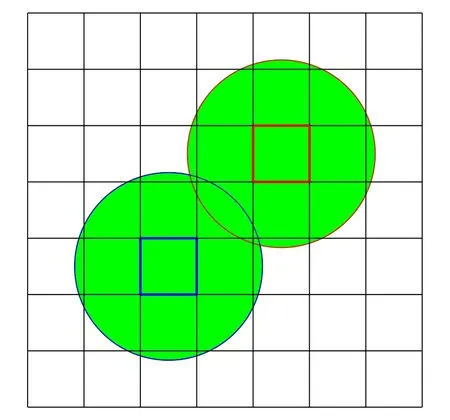

Fig.3.A schematic showing how to determine if there is lightning within each grid of 3 km × 3 km.

As mentioned above, the detection efficiency of WWLLN is relatively low.WWLLN mainly detects strong lightning pulses, and hence some weak lightning will inevitably be missed.Additionally, there are location errors (< 10 km) for lightning positions detected by WWLLN.Therefore, the strategy of artificially increasing the radius of lightning influence used by Dixon et al.(2016) was adopted.For each 3 km × 3 km grid (as described in the next section, LDA was performed on the 3-km resolution innermost domain), if there was lightning observed within 1 h prior to the assimilation time in the circular region with a radius of 5 km from the typhoon center, it was assumed that lightning occurred in this grid.As shown in Fig.3, for the blue 3 km × 3 km grid,if there is lightning within the circular region with a 5-km radius, i.e., the green shaded circle with a blue outline, it is considered that there is lightning in the blue grid.Similarly, for the red grid, if there is lightning within the circular region with a 5-km radius, i.e., the green shaded circle with a red outline, it is considered that there is lightning in the red grid.

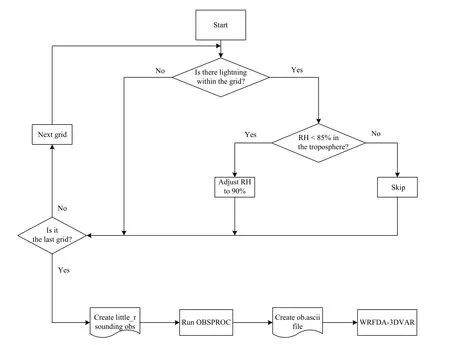

A flowchart illustrating the LDA process is shown in Fig.4.First, we checked if lightning was observed within the model grid 1 h prior to the LDA time.If there was lightning within a model grid, the RH value at levels of the troposphere in this grid column was checked.If the RH value was below 85%, it was adjusted to 90%; otherwise, it was simply skipped.After this step was completed for all the grids, the adjusted RH was output together with the model temperature and pressure as a pseudo sounding observation in LITTLE_R format [an American Standard Code for Information Interchange(ASCII)-based standard format required by WRF Data Assimilation (WRFDA)], which was then processed through the observation preprocessor (OBSPROC) module provided in WRFDA to prepare a suitable observation file (ob.ascii) for the WRF’s three-dimensional variational (3DVAR) framework, and finally assimilated in the WRFDA-3DVAR system.

Fig.4.The flowchart illustrating the LDA process.Note that OBSPROC stands for observation preprocessor.

4.2 Experimental design

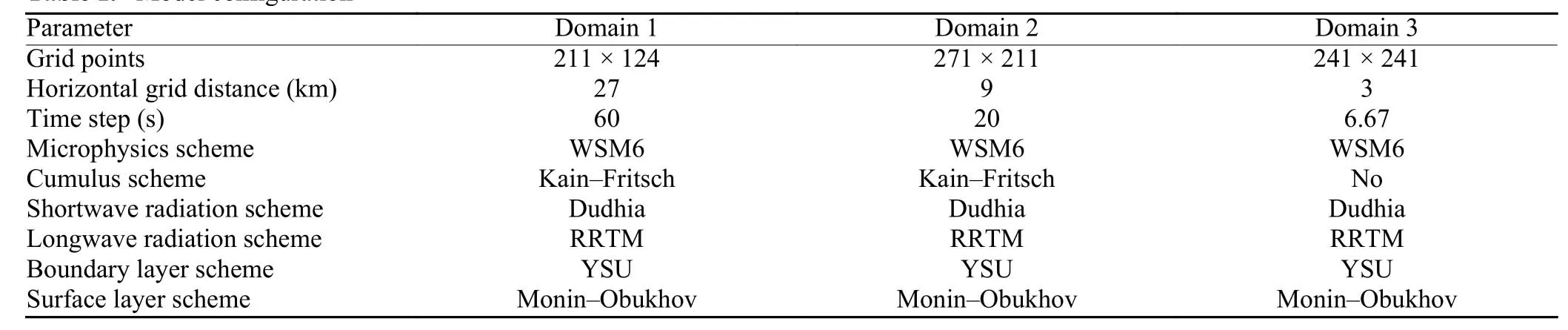

The numerical model used in this study was the threedimensional compressible nonhydrostatic WRF model with the Advanced Research dynamic solver (WRFARW version 3.5.1).Simulations were conducted in three nested domains with horizontal resolutions of 27, 9,and 3 km, respectively.The parent domain (the outermost domain) remained fixed during the whole simulation period, whereas the inner two domains were automatically moved by using WRF’s vortex-following algorithm, which updated positions of the inner two domains every 15 minutes so that they moved with and remained centered on the storm’s center.The initial and boundary conditions were provided by the NCEP Final(FNL) analysis dataset, with 1° × 1° spatial and 6-h temporal resolutions.All simulations were run with 30 vertical levels, with a 50-hPa model top.More details about the model configuration can be found in Table 1.

To examine the impact of LDA on the subsequent prediction of typhoon intensity, three LDA experiments that started at different moments were conducted: LDA_0406 started at 0600 UTC 4 November, LDA_0518 at 1800 UTC 5 November, and LDA_0606 at 0600 UTC 6 November.For comparison, a control experiment without assimilation of any observational data was conducted for each LDA experiment: CTL_0406 started at 0600 UTC 4 November, CTL_0518 at 1800 UTC 5 November,and CTL_0606 at 0600 UTC 6 November.For all the LDA experiments, the lightning data were assimilated only in the innermost domain for LDA experiments, by using the default NCEP global background error covariance (the “CV3” option in WRFDA), which was estimated from a year of differences in 24- and 48-h Global Forecast System (GFS) forecasts valid at the same time and was applicable for any regional domain (Barker et al., 2004).Also, the observation error used in this study was from the default error file “obserr.txt” provided in WRFDA, in which the RH observation error is 10%(tests with the RH observation error of 15% were also conducted, and the results were generally consistent to those with 10%; figure omitted).The results presented in the following sections are from the innermost domain of the simulations.

Table 1.Model configuration

To investigate the impact of spatial range of lightning data on the LDA results, experiment LDA_0606 was further divided into three: LDA_0606_All, which assimilated all the typhoon lightning; LDA_0606_Innercore,which assimilated only the inner-core lightning; and LDA_0606_Rainband, which assimilated only the rainband lightning.Whereas, sensitivity experiments that assimilated lightning data in different spatial ranges were not conducted for experiments LDA_0406 and LDA_0518, since the lightning data in experiment LDA_0406 were all rainband lightning and those in experiment LDA_0518 were nearly all inner-core lightning.The lightning data assimilated in LDA experiments were those that occurred within the previous one hour.In order to investigate the impact of number of LDA cycles on the subsequent forecast, four consecutive cycles at the 1-h interval were performed for each LDA experiment,and the forecasts produced by using the analysis based on different LDA cycles as the initial field were compared.

5.Results

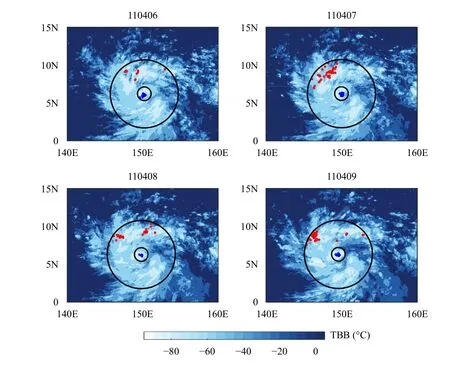

5.1 Lightning distribution during LDA

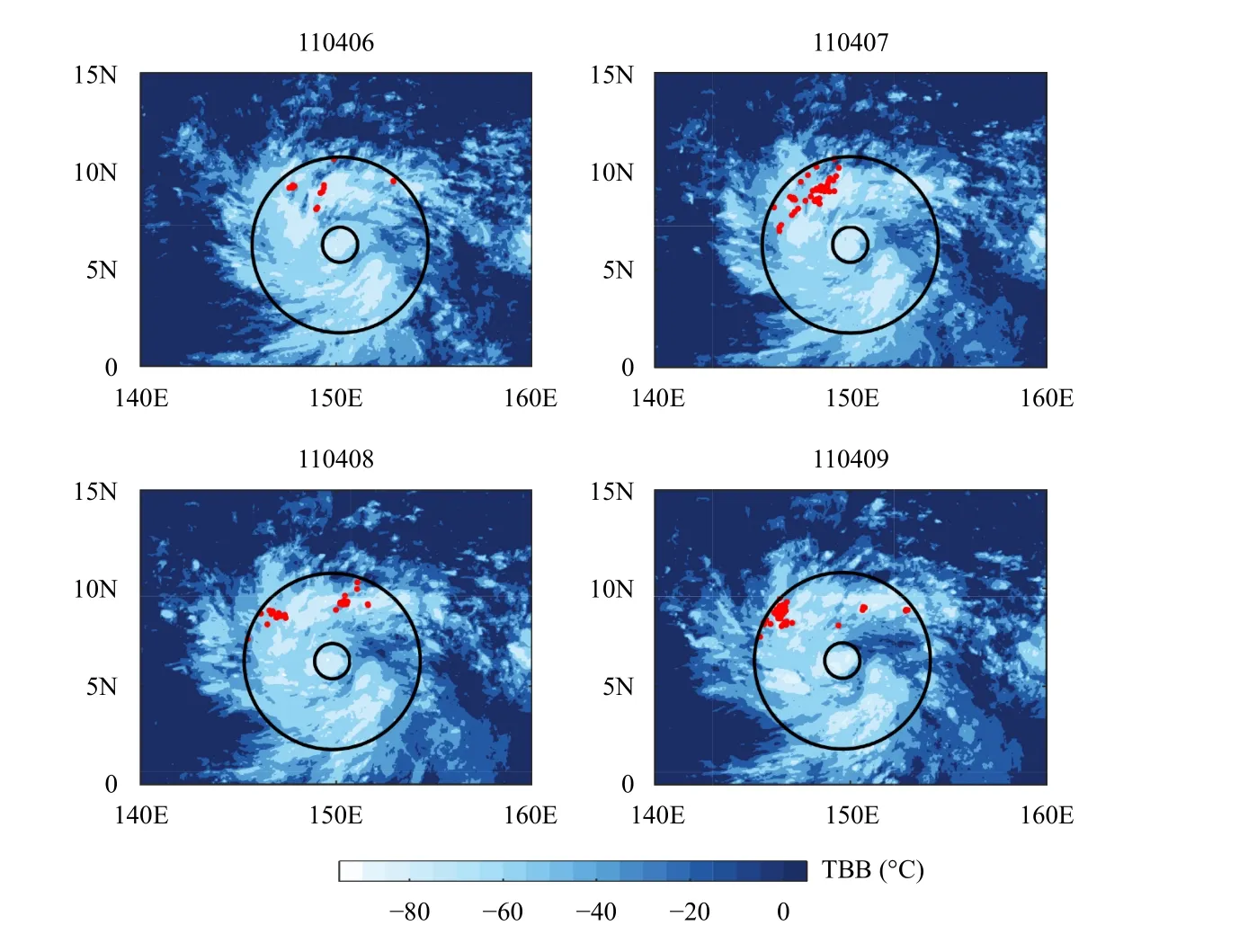

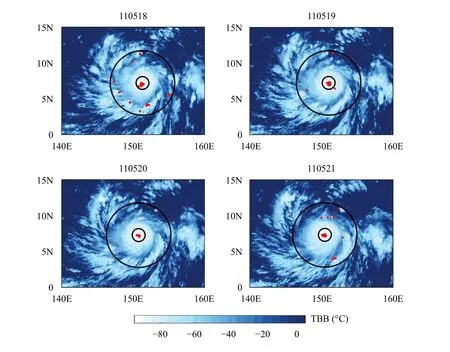

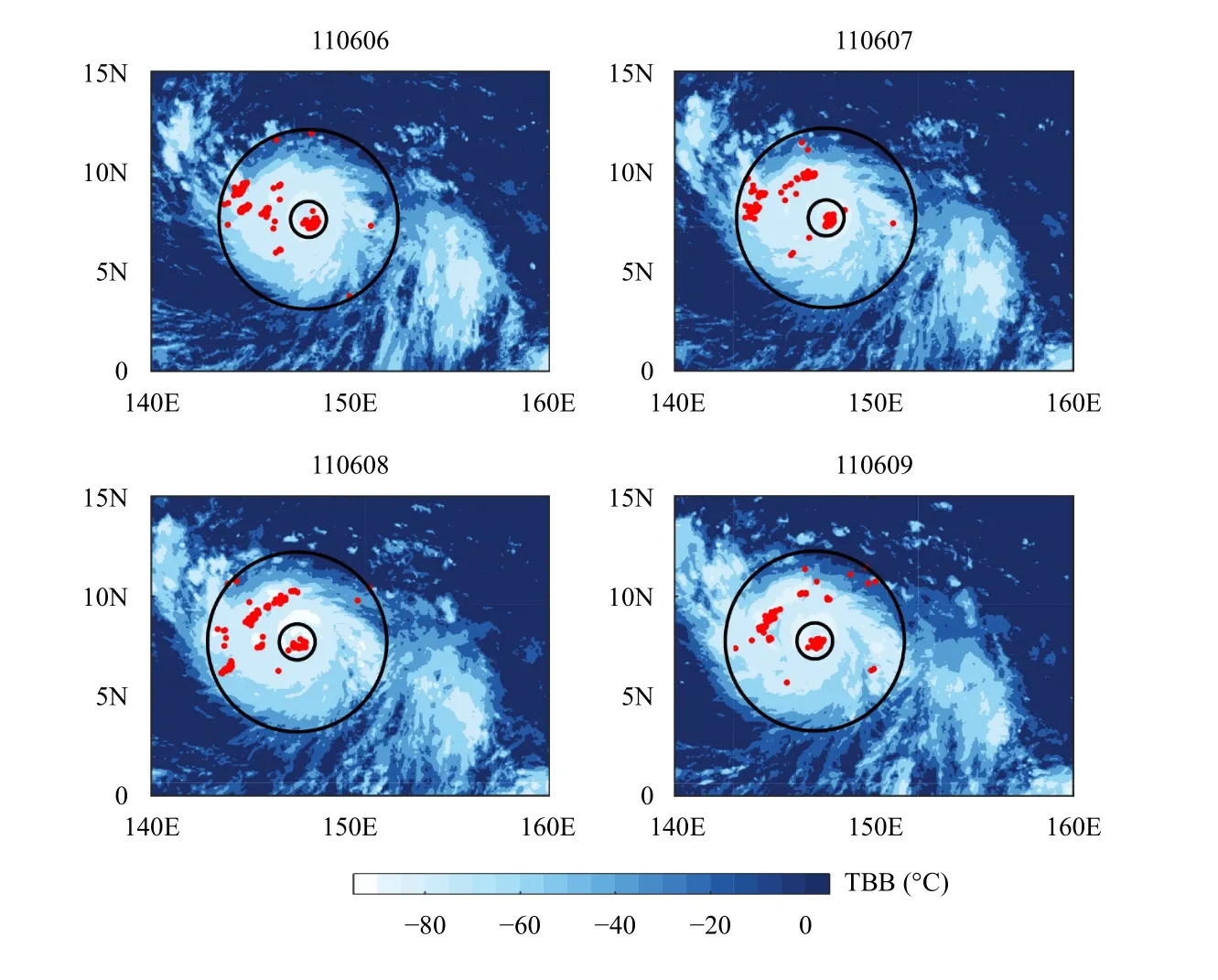

By superimposing lightning data on the infrared cloud top TBB observed byMTSAT-1R, it was found that the lightning distributions of the three LDA experiments were quite different: the lightning data used in experiment LDA_0406 were all rainband lightning (Fig.5); the vast majority of lightning data used in experiment LDA_0518 were inner-core lightning, with only a few lightning flashes scattered in the rainband region (Fig.6);whereas, the number of inner-core and rainband lightning flashes were roughly the same for experiment LDA_0606 (Fig.7).These differences in the distribution of lightning data may have affected the results of LDA experiments, which will be discussed below.

5.2 Impact of LDA on intensity forecasts

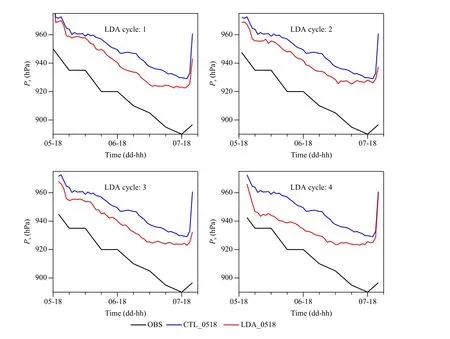

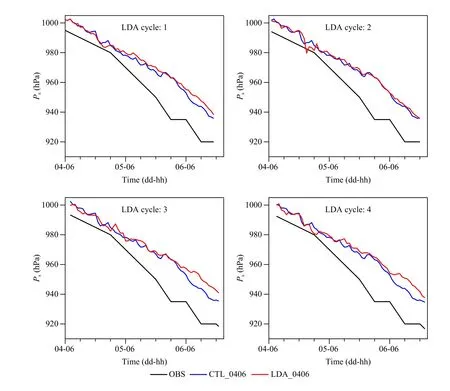

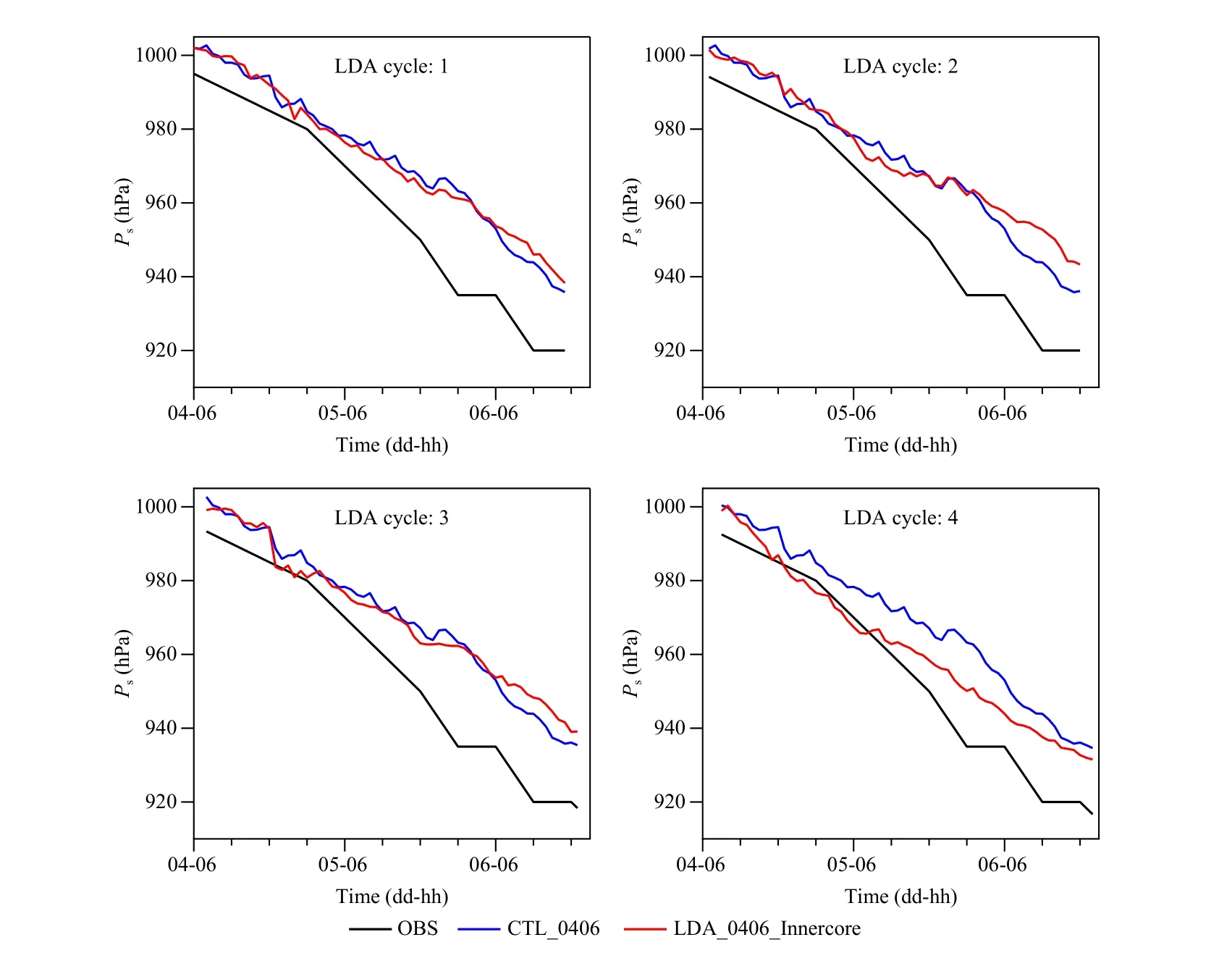

Figure 8 shows the forecasts of typhoon intensity obtained by using the four analyses from different numbers of LDA cycles in experiment LDA_0518, compared with the corresponding results from the control experiment and best-track data.It can be seen that intensity forecasts from LDA_0518 improved remarkably compared with the control experiment.Also, the improvement in the intensity forecast was maintained for about 48 h.As the number of LDA cycles increased, the improvement in the intensity forecast became more obvious.With four LDA cycles, the minimum sea level pressure was reduced on average by 13.25 hPa in the subsequent 48-h forecast.

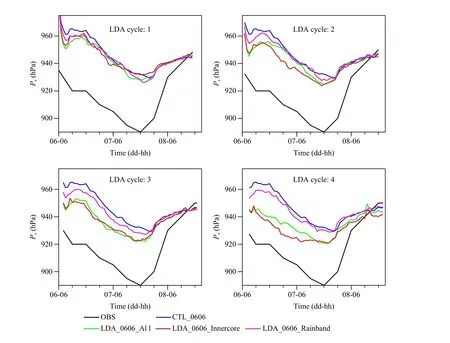

The intensity forecasts by using the four analyses of experiment LDA_0606 are shown in Fig.9, in comparison with the results from the best-track data and control experiment.It can be seen that, although there was improvement in intensity forecasts for all the three experiments (LDA_0606_All, LDA_0606_Innercore, and LDA_0606_Rainband), the degree of improvement varied.The improvement from assimilating only the innercore lightning was the greatest, followed by that from assimilating all the typhoon lightning, while the least improvement was achieved from assimilating only the rainband lightning.Also, the improvement in the intensity forecast could be maintained for about 48 h.As the number of LDA cycles increased, the improvement in the intensity forecast became more evident.With four cycles of LDA, the minimum sea level pressure was reduced on average by 15.54, 12.45, and 2.54 hPa in the subsequent 48-h forecasts for the experiments assimilating only the inner-core lightning, all typhoon lightning, and only the rainband lightning, respectively.

Fig.5.Cloud top TBB from the MTSAT-1R satellite superimposed on the WWLLN lightning data of experiment LDA_0406.The black circles represent distances of 100 and 500 km from the typhoon center.The red dots represent the lightning occurring within one hour before the assimilation time.The title of each subplot represents the assimilation time (format: mmddhh).

Fig.6.As in Fig.5, but for experiment LDA_0518.

The intensity forecasts by using the four analyses of experiment LDA_0406, as well as the results from the best-track data and control experiment, are shown in Fig.10.It can be seen that there was almost no improvement in intensity forecasts after LDA with different numbers of LDA cycles.Fig.8.Predictions of the typhoon intensity in experiment LDA_0518 using the four analyses from different numbers of LDA cycles as the initial condition (red), compared with the corresponding results from the control experiment (CTRL_0518, blue) and best-track data (black).

Fig.7.As in Fig.5, but for experiment LDA_0606.

Fig. 8. Predictions of the typhoon intensity in experiment LDA_0518 using the four analyses from different numbers of LDA cycles as the initial condition (red), compared with the corresponding results from the control experiment (CTRL_0518, blue) and best-track data (black).

From the above analyses, it can be concluded that,with the same LDA method and configuration, experiments LDA_0518 and LDA_0606 showed notable improvement in their typhoon intensity forecast as compared to the control experiment that assimilated no data;while experiment LDA_0406 yielded no obvious improvement.Except for the different background fields,one important reason behind these contrasting results may be the differences in the distribution of lightning data used for LDA.As mentioned in Section 5.1, the lightning data used in experiment LDA_0406 were all rainband lightning (Fig.5); in experiment LDA_0518,they were mainly inner-core lightning (Fig.6); whereas,the number of inner-core and rainband lightning data were roughly the same in experiment LDA_0606 (Fig.7).Furthermore, the improvement in the intensity forecast in experiment LDA_0606_Innercore, which assimilated only the inner-core lightning, was much better than that in LDA_0606_Rainband, which assimilated only the rainband lightning.Therefore, it is speculated that the absence of inner-core lightning in experiment LDA_0406 may be the reason that led to no obvious improvement in Haiyan’s intensity forecast.

Fig.9.As in Fig.8, but for experiment LDA_0606.The green line represents the forecast intensity from experiment LDA_0606_All, which assimilated all the typhoon lightning.The red line represents the forecast intensity from experiment LDA_0606_Innercore, which assimilated only the inner-core lightning.The magenta line represents the forecast intensity from experiment LDA_0606_Rainband, which assimilated only the rainband lightning.

When lightning activities are mainly distributed in the rainband region, assimilation of lightning data means that a humidity forcing is imposed on the model area away from the actual location of the typhoon center, which would have little impact on the typhoon intensity.Previous studies have found that lightning in the inner-core area is much better at indicating the typhoon intensity than that in the rainband area (Molinari et al., 1994; Pan et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015; Wang F.et al., 2017),implying that assimilation of the inner-core lightning data should be more effective in improving typhoon intensity forecast.Although some studies (DeMaria et al.,2012; Xu et al., 2017) have suggested that lightning in the outer rainbands can be an indicator of the enhancement in the typhoon strength, a clear relationship between rainband lightning and typhoon intensification has not yet been established.Therefore, whether and how the assimilation of lightning data in typhoon rainbands affects the forecast results of typhoon intensity is an issue worth of future investigation.

In order to investigate the impact of inner-core lightning in experiment LDA_0406, another sensitivity experiment (LDA_0406_Innercore) was designed.In this experiment, only the inner-core lightning was assimilated,and the rest of the settings remained unchanged.As can be seen from Fig.5, no inner-core lightning occurred during the period from 0600 to 0900 UTC 4 November.Hence, the inner-core lightning data used in experiment LDA_0518 were artificially moved into experiment LDA_0406_Innercore according to typhoon centers at the corresponding time, i.e., the inner-core lightning data used at 1800 UTC 5 November in experiment LDA_0518 were moved to 0600 UTC 4 November;those used at 1900 UTC 5 November in experiment LDA_0518 were moved to 0700 UTC 4 November;those used at 2000 UTC 5 November in experiment LDA_0518 were moved to 0800 UTC 4 November; and those used at 2100 UTC 5 November in experiment LDA_0518 were moved to 0900 UTC 4 November.Following this process, the lightning data superimposed on the satellite cloud top TBB are shown in Fig.11, in which red dots represent the lightning that originally existed within 1 h prior to the assimilation time (denoted by the title of each subplot, in the format mmddhh), and blue dots represent the inner-core lightning moved from experiment LDA_0518.This time, only the inner-core lightning moved from experiment LDA_0518 were assimilated, i.e., only blue dots in Fig.11 were assimilated.Typhoon intensity forecasts obtained from four analyses are shown in Fig.12.It can be seen that, with four cycles of LDA, the minimum sea level pressure was lower than that of the control experiment and closer to the best-track data; and the intensity bias compared to the best-track data was reduced on average by 6.64 hPa in the subsequent 48-h forecast, indicating that assimilation of the inner-core lightning is more effective for improving the forecast of typhoon intensity.

5.3 Impact of LDA on the typhoon internal structure

The temperature and pressure at the 3- and 5-km height levels at 0000 UTC 6 November (i.e., 3 h after LDA) in experiments CTL_0518 and LDA_0518 with four cycles of LDA are shown in Fig.13.It can be seen that, after four cycles of LDA, most areas of the innercore region had a warming effect, the pressure gradient increased, the warming inner-core was further enhanced,and the whole vortex system became more compact and stronger, closer to the observations (Fig.8).

Fig.10.As in Fig.8, but for experiment LDA_0406.

The primary source of energy for typhoons is the release of latent heat, which depends on the availability of moisture.Therefore, atmospheric humidity is one of the important conditions for typhoon intensification and maintenance.Through LDA, the high-value area of RH(figure omitted) was significantly increased, which would lead to the process of condensation and phase change between the hydrometeors, thereby increasing the release of latent heat into the atmosphere, enhancing the upper-level warm core and promoting the upward movement of airflow.This is probably the underlying physical mechanism for the relationship between the LDA and improved typhoon intensity forecast in this study.Such an interpretation is also consistent with previous studies in which diabatic heating and environmental humidity in the inner-core region were found to be conducive to typhoon intensification and maintenance (Kaplan and DeMaria, 2003; Wang, 2009; Wu et al., 2012; Li et al.,2014; Wu et al., 2015; Emanuel and Zhang, 2017).

Fig.11.Distributions of the lightning data in experiment LDA_0406_Innercore, including those that originally existed in experiment LDA_0406 (red dots) and those moved from LDA_0518 (blue dots) according to typhoon centers at different corresponding time moments.

Fig.12.As in Fig.10, but for experiment LDA_0406_Innercore.The red lines represent the typhoon intensity forecast obtained by using the analysis from assimilating only the inner-core lightning data moved from LDA_0518.

Fig.13.Distributions of the temperature (color-shaded) and pressure (contours) at 3- (top) and 5-km (bottom) heights at 0000 UTC 6 November from experiments CTL_0518 (left) and LDA_0518 with four cycles of LDA (right).

6.Summary and discussion

Based on previous observational analyses showing that lightning occurring in typhoons could be an indicator of the typhoon intensity, this study attempted to assimilate lightning data captured by WWLLN during Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013) into the WRF model to see if improvement could be made in the subsequent forecast of the typhoon’s intensity.The method, in which the adjustment of humidity is independent of the lightning flash rate, as developed by Dixon et al.(2016), was used to convert WWLLN lightning observations to RH.The adjusted humidity was then output as a pseudo sounding and assimilated in the 3DVAR framework of the WRF data assimilation system in the cycling mode at the 1-h interval.

Haiyan was characterized by a high proportion of lightning in the inner-core region, with 49% of the lightning occurring within a radius of 100 km from the typhoon center.The LDA experiments initiated at three different time moments were conducted.Through comparative analysis of the LDA and corresponding control experiments, as well as observations, it was found that the LDA experiments assimilating the inner-core lightning achieved obvious improvement in the typhoon intensity forecast, whereas assimilation of the rainband lightning data led to little or no improvement.Besides,the improvement in the intensity forecast became more obvious with the increase in the number of LDA cycles.Therefore, it is suggested that the assimilation of typhoon related lightning data should pay more attention to the inner-core lightning, and should be carried out in the cycling mode with at least three or four LDA cycles.The improvement from LDA waned as the forecast lead time extended.Overall, the subsequent improvement in the typhoon intensity forecast with LDA could be maintained for about 48 h.

The LDA method used in this study basically aims at promoting the convective development through the increase in RH within a prescribed neighborhood region centered at the observed lightning locations.This could improve the typhoon intensity forecast when the simulated typhoon is weaker than the observed.Note that the existence of lightning implies that convection is present,but the absence of lightning does not imply the opposite.Since lightning data only provide conditional convection information, LDA in this study cannot suppress the spurious convection based on the lightning information.Therefore, admittedly, the LDA method in this study may have a negative effect when the simulated typhoon is stronger than the observed.

The 3DVAR approach is currently widely used in research communities and operational centers, owing to its computational efficiency and robust performance.In the present study, the lightning data were assimilated in the 3DVAR framework of the WRF data assimilation system.The assimilation technique of this study may be applied in operational models.Further improvement in LDA requires more sophisticated methods, such as the 4DVAR or ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF) methods, as well as a more realistic and robust observation operator between lightning observation and model variables,which is suitable for typhoon studies.Considering that the current study was based on a single case, i.e., Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013), which was characterized by a high proportion of inner-core lightning, it is necessary to obtain general conclusions by examining more cases in future study.Nevertheless, the promising results in the current study demonstrate the considerable potential of assimilating lightning data to achieve the improved typhoon intensity forecast.

Acknowledgments.The authors are grateful to Prof.Xudong Liang of the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences for his constructive suggestions.The authors wish to thank the WWLLN (http://wwlln.net), a collaboration among over 50 universities and institutions in the world, for providing the lightning location data used in this paper.The best-track data were from Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration, and the satellite TBB data were from Kochi University of Japan.

Journal of Meteorological Research2020年5期

Journal of Meteorological Research2020年5期

- Journal of Meteorological Research的其它文章

- High-Resolution Projections of Mean and Extreme Precipitation over China by Two Regional Climate Models

- Comparison of Snowfall Variations over China Identified from Different Snowfall/Rainfall Discrimination Methods

- Evaluation and Hydrological Application of CMADS Reanalysis Precipitation Data against Four Satellite Precipitation Products in the Upper Huaihe River Basin, China

- Impacts of 1.5°C and 2.0°C Global Warming on Runoff of Three Inland Rivers in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China

- The Impact of Storm-Induced SST Cooling on Storm Size and Destructiveness: Results from Atmosphere–Ocean Coupled Simulations

- Multi-Factor Intensity Estimation for Tropical Cyclones in the Western North Pacific Based on the Deviation Angle Variance Technique