High mortality associated with gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infection in liver transplant recipients undergoing immunosuppression reduction

Fang Chen, Xiao-Yun Pang, Chuan Shen, Long-Zhi Han, Yu-Xiao Deng, Xiao-Song Chen, Jian-Jun Zhang, Qiang Xia, Yong-Bing Qian

Abstract

Key Words: Immunosuppressive therapy; Liver transplantation; Bloodstream infection; Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterium

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial infections continue to be the most common infectious complication after liver transplantation (LT), usually within 2 mo after LT[1]. Bloodstream infections (BSI) account for 19%-46% of all major infections after LT[2-5]and are associated with a mortality rate of nearly 40%[6].

Several factors are known to be associated with BSI after LT in adults, including intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative transfusion, retransplantation, longer duration of catheterization, and biliary complication. Immunosuppression (IS) is the single most important factor contributing to the incidence of infections in transplant recipients[7]. The commonly used immunosuppressive agents after LT include calcineurin inhibitor, such as tacrolimus (0.1-0.15 mg/kg/d in 2 doses) or ciclosporin (6-8 mg/kg/d in 2 doses), mycophenolate mofetil (500-1000 mg, bid), sirolimus (2 mg/d), and corticosteroids (induction with high dose methylprednisolone 500-1000 mg intravenously, followed by tapering over 5 d to maintenance with prednisone 5-20mg/d). The management of IS therapy during infection after LT is highly controversial, although IS reduction (partially discontinue or reduce the dosage of at least one IS agent) or complete withdrawal may be a generally accepted option in lifethreatening infections. To date, only few studies have assessed the impact of IS reduction or complete withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy on infection outcomes in LT recipients[8,9]. In these studies, researchers reported that immunosuppressive agents may be discontinued completely in kidney transplantation recipients since hemodialysis is an effective option in case of rejection. In contrast, complete discontinuation of IS is highly dangerous in liver transplantation because it may lead to graft loss and patient death.

This study aimed to examine the management of immunosuppressive therapy during bacterial BSI in LT recipients in the Department of Liver Surgery, Renji Hospital during a 2-year period and the effect of temporary IS withdrawal on 30 d mortality of recipients presenting with severe infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

A retrospective single-center observational cohort study was conducted in the LT recipients diagnosed with BSI in Department of Liver Surgery, Renji Hospital from January 2016 through December 2017. Overall, 1297 LT recipients were identified, including 786 children (650 Living donors and 136 deceased donors) and 511 adults. All the enrolled LT recipients satisfied the inclusion criteria: (1) 18 to 75 years of age; and (2) With diagnosis of bloodstream infection confirmed by blood culture. The patients were excluded if infection was localized or in the brain or patients died on the day of surgery. Seventy patients with 74 episodes of BSI were eligible for inclusion in this analysis. All donor organs registered in the database were donated voluntarily. No donor organs were obtained from executed prisoners.

Patient charts and in-hospital records were carefully reviewed to collect study variables and fill in the pre-determined case reports. The researchers systematically checked the integrity of the data before importing it into the database. The follow-up period was at least 180 d after the onset of index BSI. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by our institutional review board (Approval No. KY2019-160).

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

The perioperative prophylactic antimicrobial therapy included intravenous ampicillin (120 mg/kg/d, q6h) and cefotaxime (120 mg/kg/d, q6h) within 1 h before LT and lasting for 3-5 d. Methicillin-resistantStaphylococcus aureus(MRSA) nasal colonization was routinely screened when the patient was included on transplant waiting list and transferred to liver intensive care unit after the operation. Alternative regimen including vancomycin may be considered for the patients with a history of MRSA infection or colonization. The surgeon may modify the prophylactic regimen according to the history of infectious disease based on the experience of our center. Oral acyclovir or valganciclovir after intravenous ganciclovir was administered for prevention of cytomegalovirus. Antiviral prophylaxis and hepatitis B immunoglobulin therapy were given to the patients undergoing LT for managing hepatitis B cirrhosis. Routine antifungal prophylaxis was only applicable to the patients at high risk of invasive aspergillosis or candidiasis, as described elsewhere[10].

Immunosuppression strategy

Standard IS regimens include high-dose prednisone and basiliximab induction, followed by tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid, and prednisone. For the patients with unremarkable post-transplant process, steroids were withdrawn 3-6 mo after LT. A mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor was added to the treatment regimen after the first month of transplantation if patients were at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver biopsy was performed in case of elevated transaminases or laboratory results indicative of unexplained cholestasis.

The target serum level of tacrolimus was 8-12 ng/mL during the first month of LT and 6-8 ng/mL during the first 6 mo of LT. The target serum level of cyclosporin was 200-250 mg/mL during the first month and 150-200 mg/mL in the first 6 mo of LT.

Definitions

BSI was defined as the isolation of pathogenic microorganisms from at least one blood culture specimen. Positive blood culture from two separate sites was required for the skin flora associated with contamination. Polymicrobial BSI was defined as two or more microorganisms isolated from the same one blood culture specimen. Intraabdominal infections include peritonitis, peritoneal abscess, and cholangitis occurring more than 30 d after surgery. BSI was classified as secondary BSI when the pathogens from blood sample originated from the infection in other body site.

BSI source was determined according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention criteria[11]and considered as primary source when no identifiable source was available.

Multi-drug resistance (MDR) was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial classes. Carbapenem-resistantEnterobacteriaceaewas defined by current Center for Disease Control and Prevention criteria asEnterobacteriaceaestrains resistant to at least one carbapenem. For all the Gram-negative isolates, carbapenemase production (Klebsiella pneumoniaecarbapenemase, New Delhi metallo-b-lactamase, OXA-23, and OXA-51) was confirmed by simplex ‘in-house’ polymerase chain reaction assays with specific primers, including:blaKPc-related sequences (5‘-TCTGGACCGCTGGGAGCTGG-3’, forward and 5’-TGCCCGTTGACGCCCAATCC-3’, reverse);blaOXA-23-related sequences (5’-GATCGGATTGGAGAACCAGA-3’, forward and 5’-ATTTCTGACCGCATTTCCAT-3‘, reverse), andblaNDM-related sequences 5’-GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC-3’, forward and 5’-CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC-3’, reverse). Community-acquired BSI was defined as when positive blood culture was taken within 48 h since hospital admission. Hospital acquired BSI was defined as a positive blood culture obtained from patients who had been hospitalized for 48 h or longer.

For the management of immunosuppressive therapy during BSI episodes, we recorded the changes of index blood culture over a period of 7-10 d. Changes of immunosuppressive therapy were classified as follows: (1) IS was withdrawn completely when all immunosuppressive drugs were discontinued simultaneously; (2) IS therapy was partially discontinued when at least one immunosuppressive drug (steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors) was discontinued; (3) IS was reduced when the dosage of at least one immunosuppressive drug was reduced by a minimum of 50%; and (4) IS reduction was defined as at least one of the above situations.

Data collection

All relevant data were collected from the enrolled patients, including demographic data, etiology of liver disease, biopsy-confirmed rejection or medical interventions for elevated liver transaminase, and/or re-transplantation within 90 d after BSI. BSI data included the pathogenic bacterial isolates and their susceptibility patterns, empiric antibiotic treatment, as well as appropriateness and duration of antibiotic treatment. IS data included the dosage, serum level of immunosuppressive agents, and time and duration of discontinuation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Advanced Statistics Modules, version 20.0 (SPSS, Armonk, NY, United States). Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to determine the effect of MDR infection on patient survival after LT. The normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared by Student'st-test. All other non-normally distributed continuous data were presented as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and compared by Mann-WhitneyUtest.

Univariate analysis was applied to determine the risk factors for 30 d mortality in LT recipients with BSI. Only the variables showingP< 0.10 in the univariate analysis were tested in multivariate analysis. Stepwise variable logistic regression model was utilized to identify the independent risk factors for 30 d mortality of Gram-negative bacterial (GNB) infections.

RESULTS

A total of 74 episodes of BSI were identified in 70 LT recipients in the 2-year period. Most of the patients (53, 75.7%) were males with a median (IQR) age of 48 (40-51) years. The etiology of liver disease was mainly hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis (33/70, 47.1%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (20/70, 28.6%) (Table 1). The 74 episodes of BSI were classified into Gram-positive bacterial (GPB) infections (45 episodes in 42 patients) and GNB infections (29 episodes in 28 patients) based on the Gram staining of the pathogenic bacteria.

Characteristics of BSI episodes

The median (IQR) time from LT to the onset of BSI was 6 (3-20) d. Majority (67, 90.5%) of the BSI episodes occurred within 180 d after LT and were hospital acquired (94.8%). The BSI source was surgical wound (47.6%), primary (23.8%), respiratory tract (14.3%), biliary tract (11.9%), central venous catheter (4.8%), urinary tract, and intra-abdominal (2.1%) in GPB group. Intra-abdominal infection (32.1%) was the primary site of BSI, followed by biliary tract (25.0%), urinary tract (21.4%), respiratory tract (17.9%), primary (10.7%), and central venous catheter (7.1%) in GNB group. GNB group showed numerically longer withdrawal time than GPB group (12.6 dvs6.3 d) (Table 1).

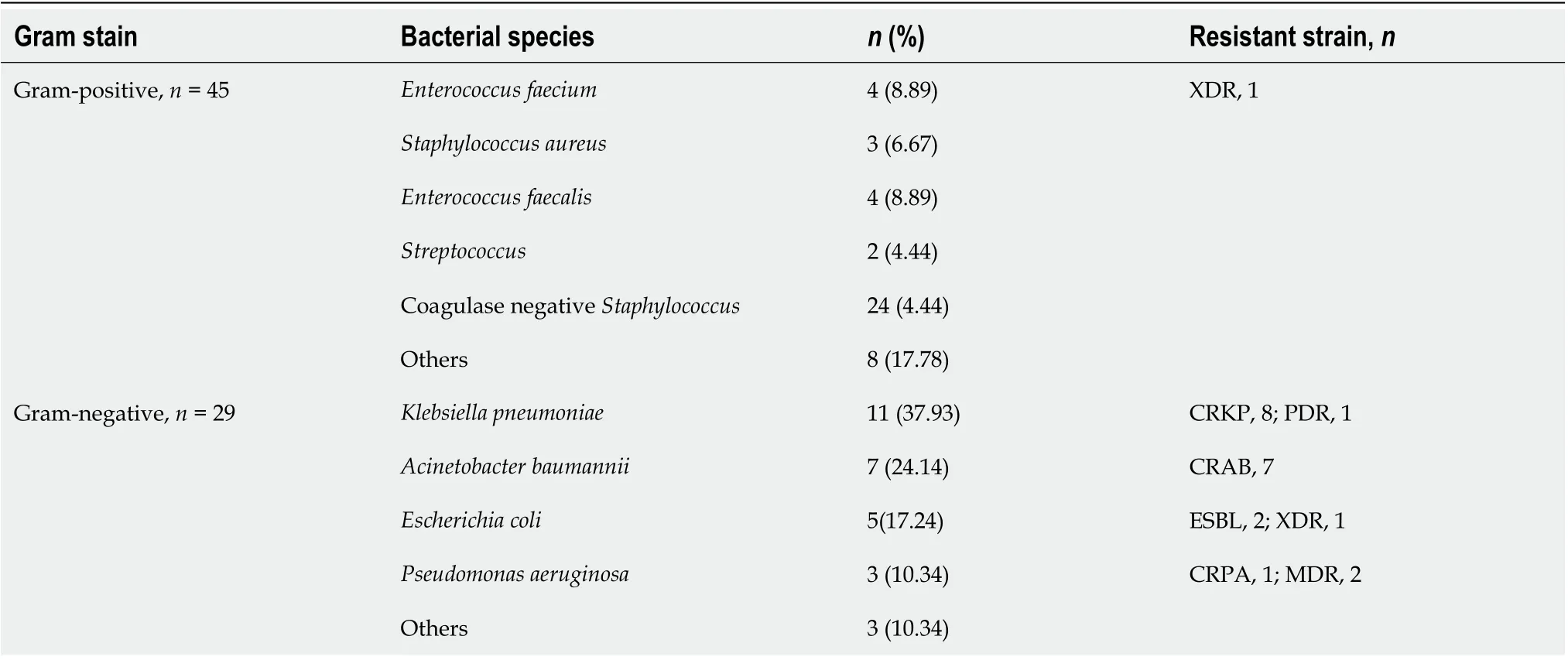

The median (IQR) time from the day of transplantation (day 0) to onset of BSI was 4 (1-6) d in GPB group (n= 45) and 12 (8-41) d in GNB group (n= 29). The distribution of bacterial species is presented in Table 2. The isolates in GPB group included coagulasenegativeStaphylococcus(n= 24),Enterococcus faecalis(n= 4),Staphylococcus aureus(n= 3),Enterococcus faecium(n= 4), andStreptococcus(n= 2). The pathogenic isolates in GNB group were mostly antibiotic resistant (n= 22, 75.9%). The etiological agents wereKlebsiella pneumoniae(n= 11, including eight carbapenemase-producing strains and one pandrug resistant strain),Acinetobacter baumannii(n= 7, all carbapenemaseproducing strains),Escherichia coli(n= 5, including two ESBL-producing strains and one extensively drug-resistant strain), andPseudomonas aeruginosa(n= 3, including two multi-drug resistant strains and one carbapenemase-producing strain).

Management of immunosuppressive therapy

IS reduction was found in 28 (41.2%) cases, specifically 5 cases (5/28, 17.9%) in GPB group and 23 cases in GNB group. As for GPB BSIs, dosage reduction was identified in 2 patients (all tacrolimus), and complete IS withdrawal in 3 patients. In the LT recipients with GNB BSIs, dosage reduction (tacrolimus, steroids, ciclosporin, and/or mycophenolate) was made in six patients. At least one immunosuppressive drug was discontinued in one patient. Both dosage reduction and discontinuation of at least one drug were identified in one patient. Complete IS withdrawal was found in 15 patients.

Outcome analysis

Fifty-seven patients completely recovered from infectious complications, including 40 (95.2%) in GPB group and 17 (60.7%) in GNB group. The 180 d all-cause mortality rate was 18.6% (13/70). The 2 deaths in GPB group were due to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The 11 deaths in GNB group were attributed to worsening infection secondary to IS withdrawal. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the patients with MDR GNB infections had significantly lower 90 d survival rate than the patients without MDR GNB infections (50%vs100%, log-rank test,P= 0.03) after onset of BSI.

Three patients (7.1%) developed suspected rejection episodes in GPB group, while seven patients (25%) developed rejection episodes in GNB group.

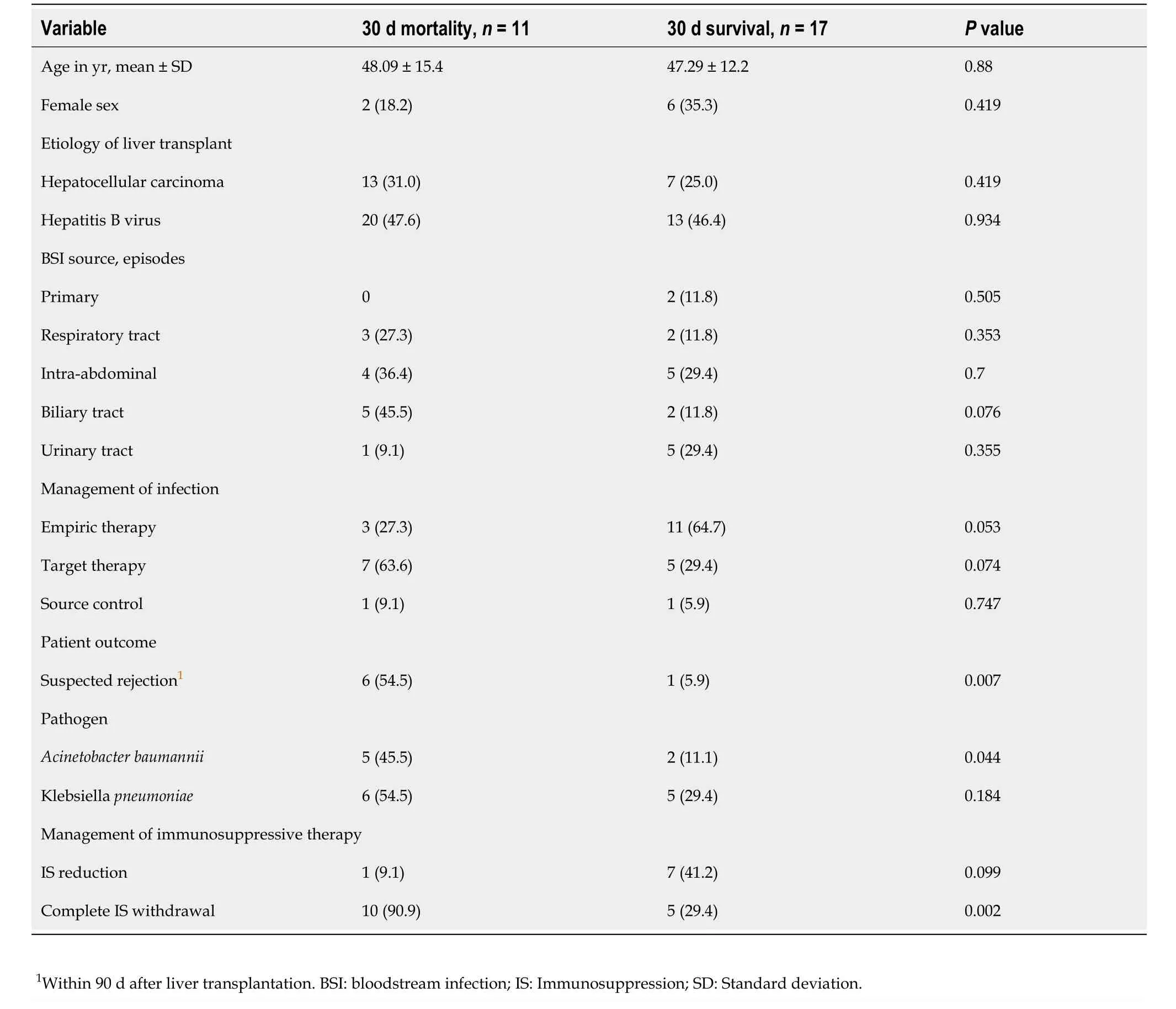

In patients with GNB infections, patients who died within 30 d of infection diagnosis showed a higher prevalence of rejection, a higher risk ofKlebsiella pneumoniaeinfection, and a more frequent presentation with IS withdrawal; all of these differences reached statistical significance. No differences in the 30 d mortality were found, taking into account patient primary disease or based on the source of infection. In addition, there were no differences between the episodes in which the antimicrobials were used as empiric therapy or target therapy (Table 3).

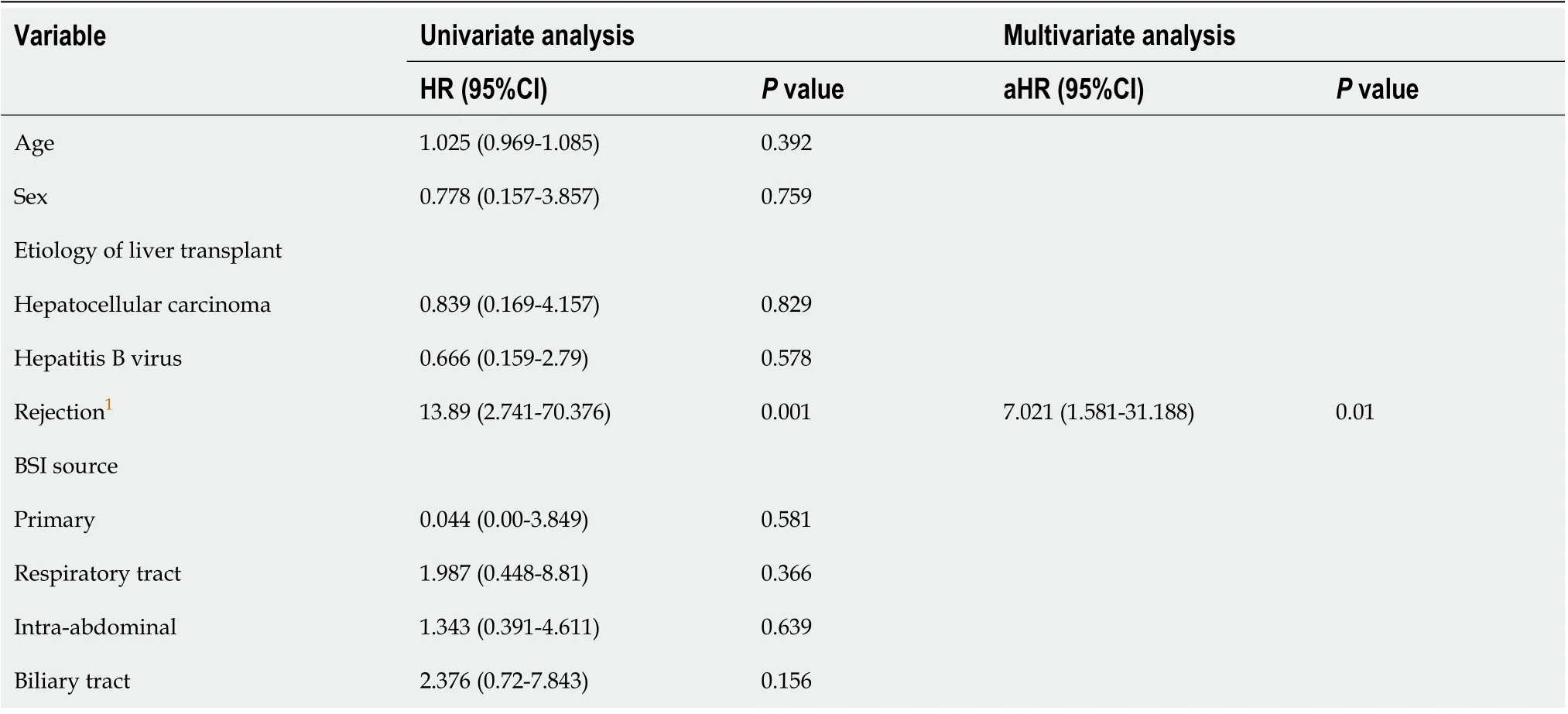

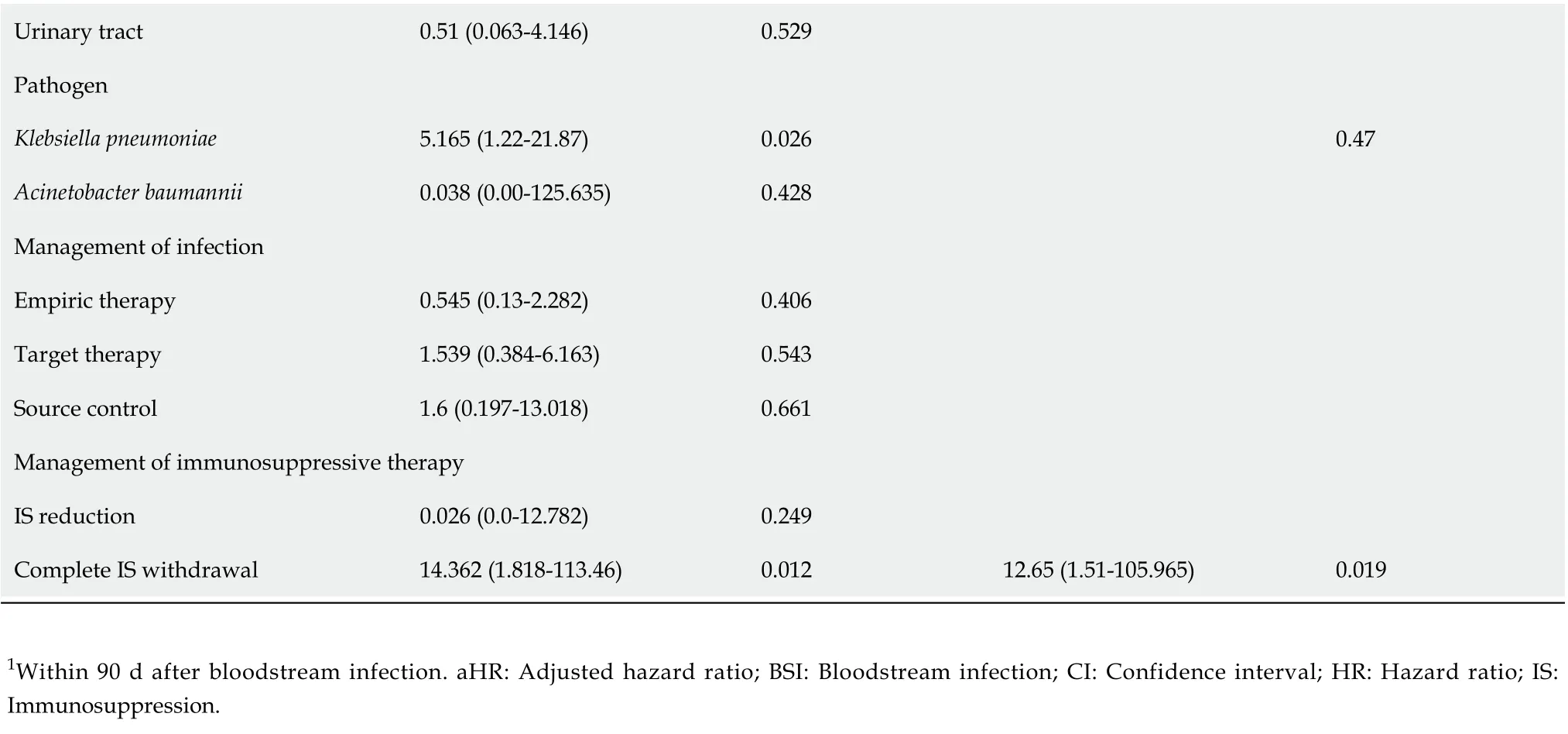

Univariate analysis showed that rejection within 90 d after BSI,K. pneumoniaeinfection, and complete IS withdrawal were significantly associated with 30 d mortality of GNB infections after LT. Multivariate analysis indicated that rejection within 90 d after BSI (P= 0.01) and complete IS withdrawal (P= 0.019) were independent predictors of 30 d mortality in patients with GNB infections (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that BSI is a common complication in LT recipients. At least one BSI episode was identified in 14.5% (74/511) of LT recipients in the first year after transplantation. This is consistent with the previous reported incidence of 28%-46%[5,12]. Previous studies demonstrated that one important high risk factor for bacterial infection in patients after solid organ transplantation was post-transplant IS therapy[13,14], which was supported by a hypothesis that post-transplant IS can reduce inflammatory cascades. This is considered one of the main pathophysiological factors of sepsis. Therefore, it is a common option for clinicians to reduce or discontinue immunosuppressive therapy when transplant recipients experience severe infection.

Table 1 Characteristics of liver transplant recipients with bloodstream infection in terms of bacterial pathogens, n (%)

Nearly half of the LT recipients with BSI in our study were managed with either dosage reduction or discontinuation of IS treatment. Of the 28 patients managed with IS reduction, only 5 were managed with either dosage reduction or discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in GPB group. Twenty-three patients were managed with either dosage reduction or discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy in GNB group. In addition, we found that IS withdrawal was common in the patients with MDR GNB infections and associated with increased risk of mortality. However, discontinuation of immunosuppressive regimens did not increase the risk of death in patients with GPB infection.

Few studies are available to evaluate the effect of IS reduction on the outcome of patients with bacterial infection. Ma?ezet al[8]showed that 31 LT recipients discontinued immunosuppressive drugs temporarily because of severe opportunistic infection, and 41% of these patients died while in the hospital. However, none of them had BSI or sepsis. A recent study[15]described the management of immunosuppressive therapy at the time of diagnosis of BSI in LT recipients. Ninety cases (43%) were managed with “IS reduction”, which was associated with worse outcome in LT recipients with BSI. We also found the same negative correlation between IS reduction and 30 d mortality in patients with drug-resistant bacterial infection in GNB group. The patients with severe infections or septic shock in our center were more likely to be managed by lowering the dose of or withdrawing immunosuppressive agents, but such a practice may have led to the worse outcome.

In patients with GPB BSI, the incidence of graft rejection was 7.1%, and mortality was 4.8% (n= 2). Both patients died from GVHD. In the patients with GNB BSI, the risk of graft rejection was earlier and higher (25.0%) and the mortality was 39.3%. All the deaths except one (GVHD) were due to worsening infection secondary to IS withdrawal. These findings suggest that IS less intense in those cases. The deaths were more likely associated with epidemiologic and technical-surgical factors. Another possible explanation is that IS reduction may put the patients at risk of graft rejection, which in turn leads to graft dysfunction, graft loss, or death[16].

We found that all the BSI episodes occurred in the first 180 d after LT. This was consistent with the previous reports, which confirmed early-onset BSI and other complications[3,10,17-19]. Sgangaet al[20]reported that 28% of transplant recipients developed BSI in the first 60 d after LT. In a Japanese study, 34.3% of LT recipients developed BSI in the first 90 d after LT and had a higher mortality rate than the recipients without BSI[3]. Kimet al[2]also reported that recipients with early-onset BSI were at a significantly higher risk of mortality compared to those without infection or infection without bacteremia. Several factors have contributed to the increased risk of early bacterial infection, including complexity of surgical procedures, high level of IS due to rejection, multiple entries for microorganisms (e.g., incisions, catheters, and probes), and poor performance status[21-23].

GPBs were previously considered to be the key BSI pathogens after transplantation[5,24,25]. However, current research identified GNBs as the predominant pathogens[26-28]. We found in this study that GPBs were more frequently isolated than GNBs (60.8%vs39.2%). Meanwhile, we found a high prevalence of infections caused by MDR GNB, includingAcinetobacter(24.14%), andEnterobacteriaceae(37.93%), mainly carbapenem-resistant strains. MDR GNB pathogens in LT recipients have increased worldwide, with a prevalence of over 50%. MDR GNB infections are associated with higher mortality rate than GPB infections[29,30]. Previous studies reported that MDR GNB infections were common in LT recipients[26,31,32]. A cohort study of 475 LT recipients demonstrated that MDR GNB infections were associated with higher mortality (50%)[13].

The common pathogens of infection after LT includeE. coli,Klebsiella,Enterobacter, andS. marcescens[27,33].P. aeruginosaandA. baumanniiare also common causes of GNB infection. The prevalence of ESBL-producing GNB, carbapenem-resistantK. pneumoniae(CRKP), MDRAcinetobacter, and MDRPseudomonasare on the rise and are associated with higher rate of treatment failure[13]. Importantly, we found that infection due to MDR GNB was one of the strongest predictors of post-LT mortality. The 90 d mortality was as high as 50% for the patients with MDR GNB infections. These findings are consistent with two recent studies showing that when LT patients were infected with CRKP, the 1-year survival dropped dramatically from 86 % to 29 % andfrom 93% to 55%, respectively[34,35].

Table 2 Distribution of the bacterial pathogens causing bloodstream infections in liver transplant recipients

As prior studies reported[2,26,27], the most frequent sources of BSIs in our study were intra-abdominal and biliary tract in GNB group. Intra-abdominal infection largely occurred in the first 3 mo, while cholangitis was the major source of BSI at later time. Reduction of biliary complications was thought to be an important factor for lower incidence of bacteremia, especially in living-donor liver transplantation because biliary tract is one of the most common port of bacterial entry due to the complexity of liver transplantation procedures[2]. Similar to previous reports[36-38], the primary site of infection was not identified in 17.6% of the cases in this study, probably due to early proactive antibiotic therapy and the difficulty of identifying intra-abdominal and biliary sources. Georgeet al[38]reported that many episodes of primary bacteremia were associated with biliary leakage, hepatic infarction, or abdominal fluid. Bile leakage or biliary stenosis is a major postoperative complication, with an incidence of 10%-15% in deceased donor LT and 15%-30% in living transplantation recipients[39,40].

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, this is a retrospective single center and small size study. Secondly, the number of BSI episodes may have been underreported. Finally, variability in immunosuppressive management may exit when comparing our findings with the practice in other medical centers.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, IS reduction is surprisingly more common in cases of GNB than GPB BSIs in the LT recipients. MDR GNB infection may put LT recipients at higher risk of graft rejection and death than GPB infection. Rejection and complete IS withdrawal are the independent predictors for the 30 d mortality in patients with GNB infection. Complete IS withdrawal should be done cautiously due to increased risk of mortality in the LT recipients complicated with GNB infection. A multidisciplinary approach, timely and appropriate successful antimicrobial therapy, and source control, when necessary, may be safer and more effective than IS reduction therapy in recipients with BSI after LT.

Table 3 Relationship of clinical and therapeutic variables with outcomes in patients with Gram-negative bacterial infections, n (%)

Table 4 Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of risk factors for 30 d mortality after Gram-negative bacterial infections in liver transplant recipients

Urinary tract 0.51 (0.063-4.146)0.529 Pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae 5.165 (1.22-21.87)0.026 0.47 Acinetobacter baumannii 0.038 (0.00-125.635)0.428 Management of infection Empiric therapy 0.545 (0.13-2.282)0.406 Target therapy 1.539 (0.384-6.163)0.543 Source control 1.6 (0.197-13.018)0.661 Management of immunosuppressive therapy IS reduction 0.026 (0.0-12.782)0.249 Complete IS withdrawal 14.362 (1.818-113.46)0.012 12.65 (1.51-105.965)0.019 1Within 90 d after bloodstream infection. aHR: Adjusted hazard ratio; BSI: Bloodstream infection; CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; IS: Immunosuppression.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Bacterial infections continue to be the most common infectious complication after liver transplantation (LT), usually within 2 mo after LT. Immunosuppression (IS) is the single most important factor contributing to the incidence of infections in transplant recipients.

Research motivation

The management of IS therapy during infection after LT is highly controversial, although IS reduction (partially discontinue or reduce the dosage of at least one IS agent) or complete withdrawal may be a generally accepted option in life-threatening infections. Few studies are available on the management of IS treatment in the LT recipients complicated with infection.

Research objectives

To describe our experience in the management of IS treatment during bacterial bloodstream infection (BSI) in LT recipients and assess the effect of temporary IS withdrawal on 30 d mortality of recipients presenting with severe infection.

Research methods

A retrospective study was conducted with the patients diagnosed with BSI after LT in the Department of Liver Surgery, Renji Hospital from January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2017. All recipients diagnosed with BSI infections after LT were included in this study. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of risk factors for 30 d mortality was conducted in LT patients with Gram-negative bacterial (GNB) infections.

Research results

Seventy-four episodes of BSI were identified in 70 LT recipients, including 45 episodes of Gram-positive bacterial (GPB) infections in 42 patients and 29 episodes of Gramnegative bacterial infections in 28 patients. Overall, IS reduction (at least 50% dose reduction or cessation of one or more immunosuppressive agent) was made in 28 (41.2%) cases, specifically, in 5 (11.9%) cases with GPB infections and 23 (82.1%) cases with GNB infection. The 180 d all-cause mortality rate was 18.5% (13/70). The mortality rate in GNB group (39.3%, 11/28) was significantly higher than that in GPB group (4.8%, 2/42) (P= 0.001). All the deaths in GNB group were attributed to worsening infection secondary to IS withdrawal but the deaths in GPB group were all due to graft-versus-host disease. GNB group was associated with significantly higher incidence of intra-abdominal infection, IS reduction, and complete IS withdrawal than GPB group (P< 0.05). Cox regression showed that rejection (adjusted hazard ratio 7.021,P= 0.001) and complete IS withdrawal (adjusted hazard ratio 12.65,P= 0.019) were independent risk factors for 30 d mortality in patients with GNB infections after LT.

Research conclusions

IS reduction is more frequently associated with GNB infection than GPB infection in LT recipients. Complete IS withdrawal should be cautious due to increased risk of mortality in the LT recipients complicated with BSI.

Research perspectives

IS reduction may be a generally accepted option in life-threatening infections after LT. However, this practice must be discussed thoroughly, as it seems to be associated with worse outcome in patients with BSI. A multidisciplinary approach, timely and appropriate successful antimicrobial therapy, and source control, when necessary, may be safer and more effective than IS reduction therapy in recipients with BSI after LT.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年45期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年45期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Discovery of unique African Helicobacter pylori CagAmultimerization motif in the Dominican Republic

- Diagnosis and treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in gastrointestinal bleeding: A systematic review

- Association between ADAMTS13 activity–VWF antigen imbalance and the therapeutic effect of HAIC in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

- Liver fibrosis index-based nomograms for identifying esophageal varices in patients with chronic hepatitis B related cirrhosis

- Nimbolide inhibits tumor growth by restoring hepatic tight junction protein expression and reduced inflammation in an experimental hepatocarcinogenesis

- Role of pancreatography in the endoscopic management of encapsulated pancreatic collections – review and new proposed classification