How knowledge of hepatitis B disease and vaccine influences vaccination practices among parents in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Giao Huynh, Le An Pham, Thien Thuan Tran, Ngoc Nga Cao, Thi Ngoc Han Nguyen, Quang Vinh Bui

1Faculty of Public Health, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

2Center for Training of Family, Medicine University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

3Department of Infectious Diseases, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

4Infection Control Department, University Medical Center at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

5Department of Pediatrics, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Knowledge; Hepatitis; Health Belief Model;Vaccination; Questionnaire

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has had a worldwide distribution, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)estimated that 887220 people died from illnesses relating to HBV infection globally in 2015[1]. Most of the burden of HBV related disease was due to either vertical transmission at birth or horizontal transmission in children under 5 years[2]. Infection acquired early in life was more likely to become chronic than an infection acquired in later childhood. The results of the child having a chronic HBV infection was 90% if the child was infected at birth. The rate of 30% for chronic infection if infected between 1 and 5 years of age and only 5%-10% if infected after 5 years of age[2,3]. Vietnam has a high prevalence of HBV infection and burden hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with 9.1% chronic HBV, 24.6% HCC and the country is ranked 5 out of the top 10 countries in the world with the highest incidence rate of liver cancer with chronic hepatitis B and C being identified as major causes of liver disease such as cirrhosis and HCC[4], and viral hepatitis was the fourth leading cause of mortality in Viet Nam[5]. The main mode of HBV transmission was a mother to child transmission (MTCT) during childbirth or early childhood, chronic hepatitis B[6]. Hepatitis B was prevented by the currently available safe and effective vaccine and utilized widely in Vietnam through the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI)since 2003 for children under 1 year of age. They received a birth dose and 3 doses of the HBV vaccine at 2, 3 and 4 months. In 2003,a study in Thanh Hoa province suggested that 12.5% of the children(9-18 months old) and 18.4% of children aged 4-6 years were infected with HBV[7]. However, a national study in 2014 surveyed hepatitis B surface Antigen in children who had received the full dose HBV vaccine and found that the overall HBsAg prevalence was only 2.7%, which showed dramatic reductions in the prevalence of HBV infection among children born since the HBV vaccine was introduced into the EPI in Vietnam[8]. That showed vaccination programs against hepatitis B were very effective. This was also demonstrated in many other countries. A dramatic decrease in the incidence of HCC (60.1%), mortality due to fulminant hepatic failure (76.3%) and mortality due to chronic liver diseases (92.0%)where observed in Taiwan since HBV vaccine was introduced[1]and the same results were reported among Chinese children aged 0-9 in China[9]. However, in Vietnam in 2013, following media reports of three deaths after immunization with hepatitis B birthdose vaccination and pentavalent DPT-Hib-Hepatitis B vaccine(Quinvaxem), there was a dramatic decline in the birth dose coverage to nearly 55%. This occurred directly after the events were publicized in media[10], however, the rate again rose to almost 70%in 2015-2016[11]and HBV3 coverage has also been influenced by such events. In addition, the health care providers were also impacted by adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) (e.g.perceptions of vaccine contraindications)[5]. Although the WHO supported the conclusion that the hepatitis B vaccine was effective and safe, the infant deaths and media reports could have lead to parents’ fears over vaccine safety and reduced the rate of vaccination coverage of children[12]. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to assess the knowledge of parents about HBV infection and their associations with the full and timely practice of HBV vaccination for their children.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Study population

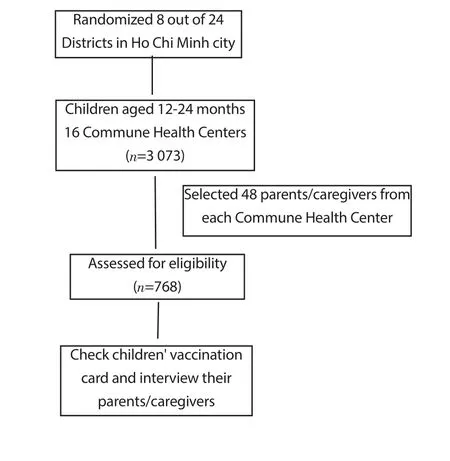

A prospective cross-sectional survey on HBV vaccination was conducted between February 2016 and July 2017. Parents and their children aged between 12 and 24 month-old who attended at 16 community health centers (CHCs) in Ho Chi Minh City and had the vaccination cards, were eligible (Figure 1). A sample size of 768 was determined using single population proportion formula with the proportion (p) of the study was assumed 50% because no similar studies in Vietnam, 95% level of confidence, degree of precision(d) 5% and design effect was 2.0. Ho Chi Minh city is the most populous city in Vietnam with a population of 8.4 million as of 2017.The city now comprises 19 districts and 5 suburban districts.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the research methodology.

2.2. Data collection

A structural questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first one consisted of 15 items that obtained demographic information of parents and their children. The second consisted of 11 closeended items which related to parents’ knowledge about hepatitis B,which were based on four domains that indexed the Health Belief Model (HBM)[13]and Bigham and Ma GX’s questionnaires, which were tested for validity and reliability and an overall Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.63 was reported for the HBM Scale[14,15],and keywords were used in related to our previous studies[16,17].The questionnaires were given to a group of experts in hepatitis and vaccination to examine them for validity. The feedback from the experts was then used to clarify the questionnaires. A pilot test was then conducted among 25 mothers attending vaccinations at a CHC’s. Questions were then modified for legibility by participants.Parents were interviewed face to face and all questions were presented and recorded. All the questions were objective with ‘Yes’or ‘No’ as the options. Definitions main outcomes about full and timely HBV vaccination which based on the children’s vaccination records, complete and timely vaccination was defined as the child received a birth dose on schedule within 24 hours of birth and 3 doses of the HBV vaccine on time in the EPI in Vietnam (children aged 2 months , 3 months, and 4 months).

We evaluated the complete and timely vaccinations based on their vaccination records. The HBM as a theoretical framework to evaluate parents’ knowledge regarding HBV, included: (1) Perceived susceptibility to HBV infection. (2) Perceived severity of HBV infection. (3) Perceived benefits, and (4) Barriers of vaccination.

2.3. Data analysis

The internal reliability of the data was measured by Cronbach’s alpha. The knowledge was assessed through the 11 item questions.A scoring system was used to estimate the overall knowledge level.Each correct answer was given one score, and the range of the score varied between 0 (with no correct answer) and 11 (for all correct answers).The data was calculated using Stata 13 and Epidata 3.1 software.Means, standard deviations and frequencies, percentages were used to describe the data. To compare characteristics between two subgroups of HBV vaccination, Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests and t tests were used when appropriate. Multiple logistic regression was also used to identify factors associated with full and timely HBV vaccination, a P value <0.05 was considered as statistically different.

2.4. Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Council-University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (protocol number 125/UMP-BOARD). All subjects agreed and gave informed consent before taking part in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of parents and children

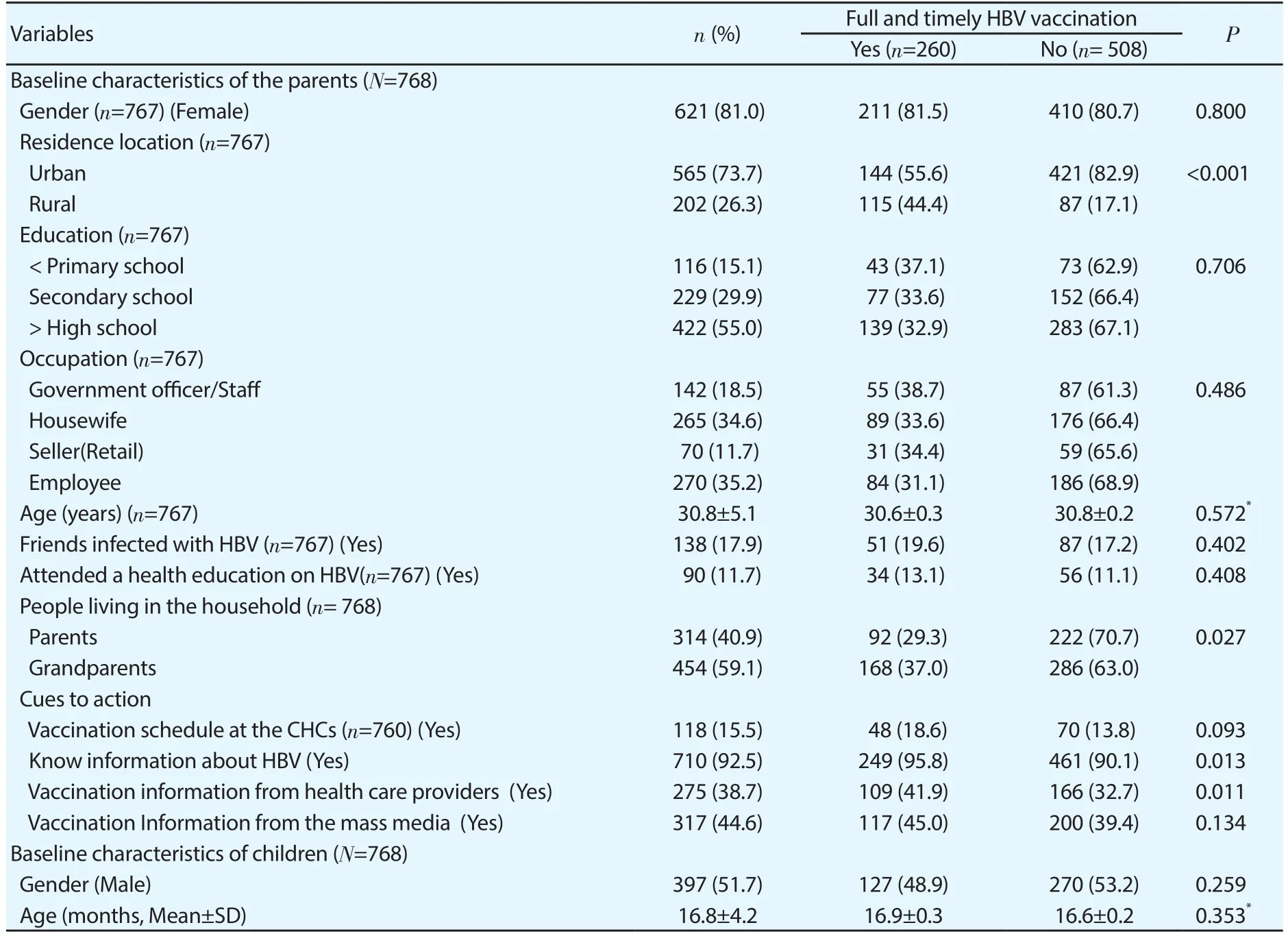

A total of 768 eligible parents recruited in our study had a mean age of (30.8±5.1) years. Among these, 621 (81.0%) were female,majority were employee (35.2%), a majority of parents (55.0%)reported receiving a high school education, the majority of them lived in urban areas (73.7%), only 11.7% of parents attended a health education session on hepatitis B. Most of parents had heard about HBV information (92.5%), in which 38.7% and 44.6% from health staff and the mass media, respectively. Their children had a mean age of (16.8±4.2) months. Of the 768 children, 397(51.7%) were male (Table 1). In relation to vaccination practice, only 260 (33.9%)of children were neither delayed nor refused hepatitis B vaccination(data not shown).

Table 1. Sample characteristics by vaccination practice.

3.2. Knowledge of HBV infection by HBM framework

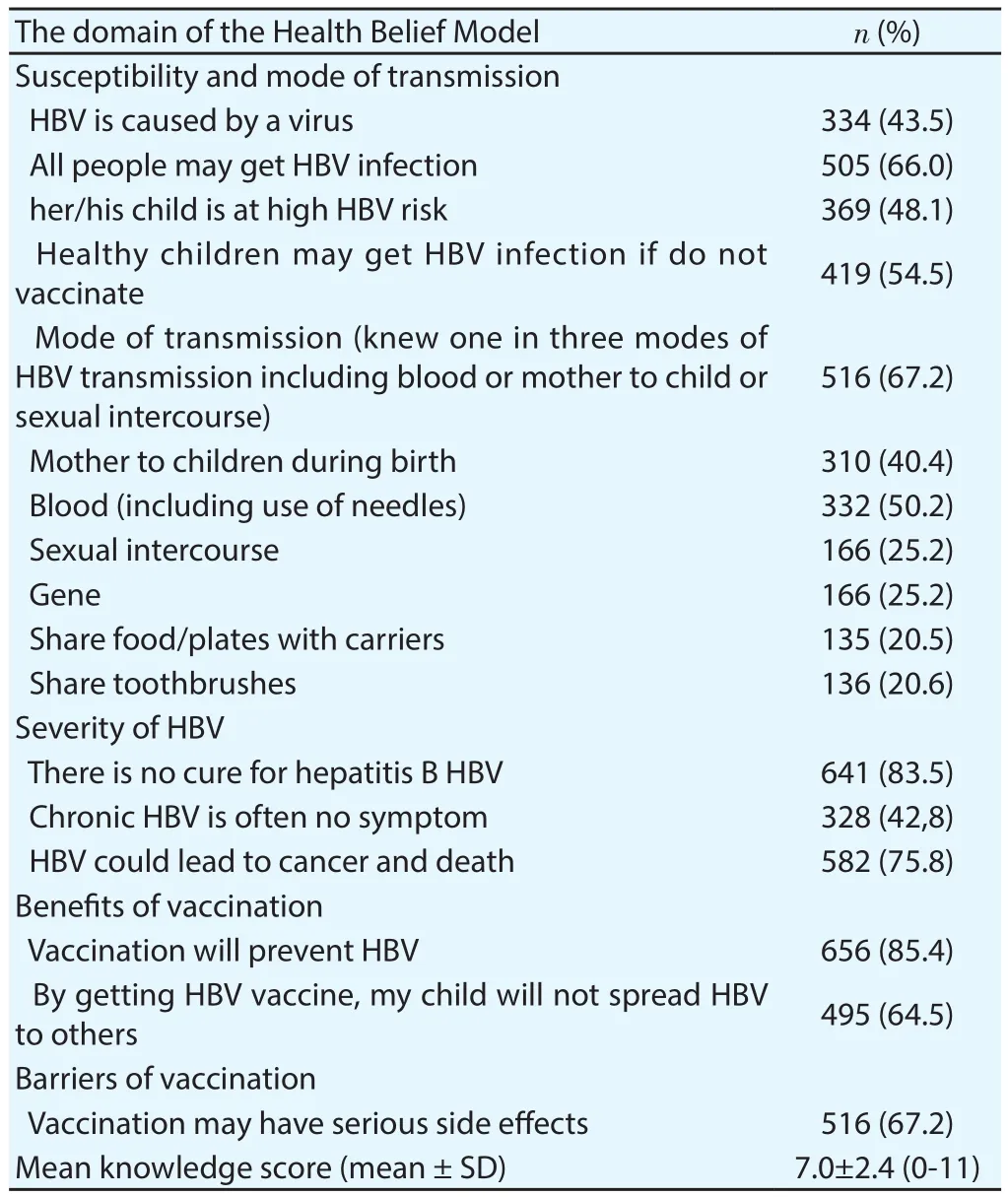

The mean knowledge score was (7.0±2.4) (0-11). An overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient score for our questionnaire was 0.67,reflecting an acceptable internal consistency. The responses of the parents regarding their knowledge towards hepatitis B disease were depicted in Table 2. Nearly half of parents (43.5%) knew HBV is caused by a virus, 48.1% of parents knew that their children were at high risk for HBV, 66.0% of them recognized all people may get HBV infection and 54.5% believed their children were also at higher risk if they do not get vaccinated. There was a misconception of parents reported on the modes of transmission, that the HBV could be transmitted through sharing food/plates with carriers (20.5%),sharing or using toothbrushes (20.6%), genetic inheritance (25.2%).A total of 40.4%, 50.2%, 25.2% and 26.1% of parents knew that the HBV was transmitted from mother to child during birth, through blood, sexuality and using needles. With respect to perceived severity, 83.5% and 42.8% of parents knew that HBV infection was serious and asymptomatic, respectively. With respect to perceived benefits, many parents tended to recognize that HBV vaccination helped to prevent transmission to others (64.5%). In addition, when their children got the HBV vaccine they reported that they would not worry about liver disease (85.4%). Regarding barriers, 67.2%of parents received information about the serious side effects after vaccination.

Table 2. Percentages of respondents answering “Yes” to the knowledge of HBV by HBM framework (N=768).

3.3. Association between sample characteristics, parents’knowledge and HBV vaccination

There was an association between the HBV vaccination status of children and sample characteristics. Univariate analysis indicated that in cases where the children’s parents were living in the rural areas, and the children were living with grandparents and parents,also parents received information about HBV from health workers,higher rates of children received full and timely HBV vaccination than those who did not (Table 1).

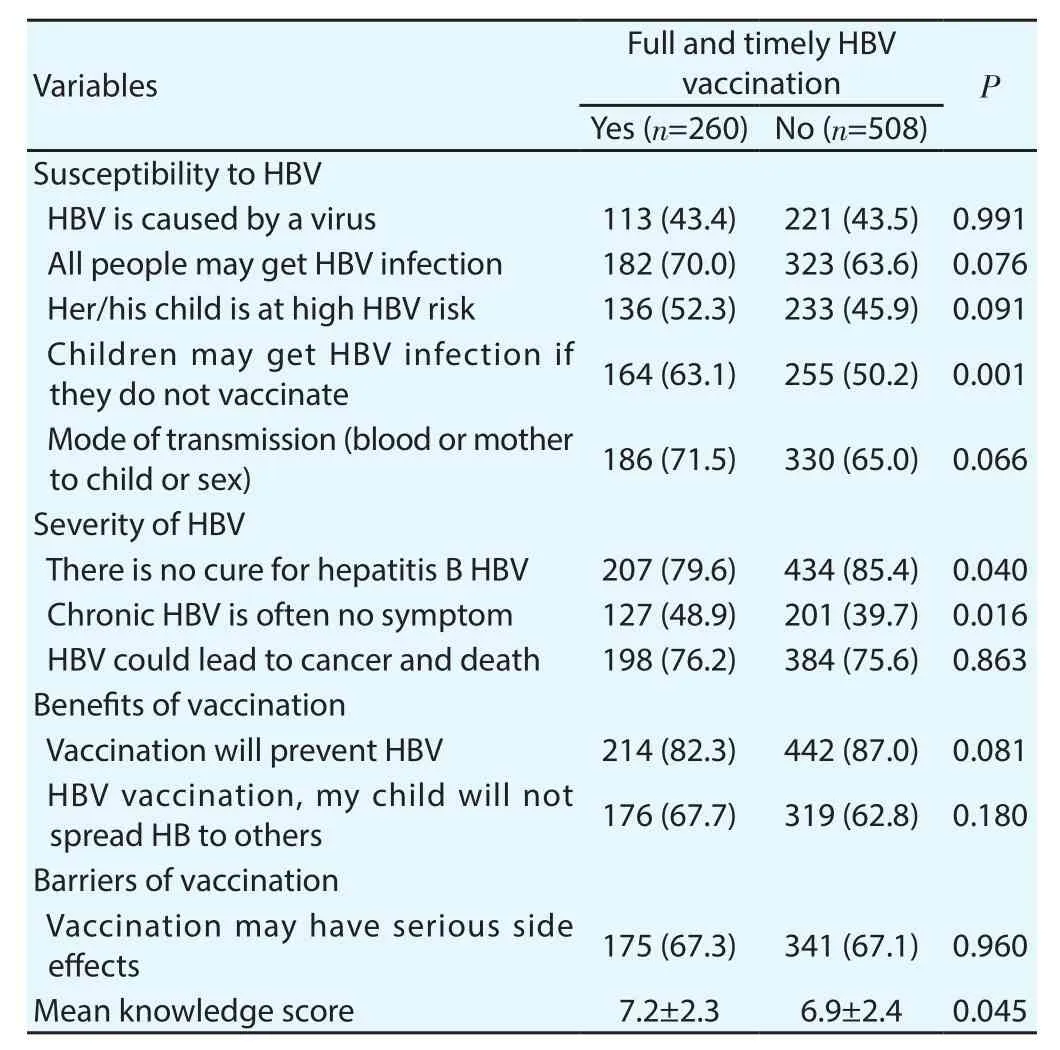

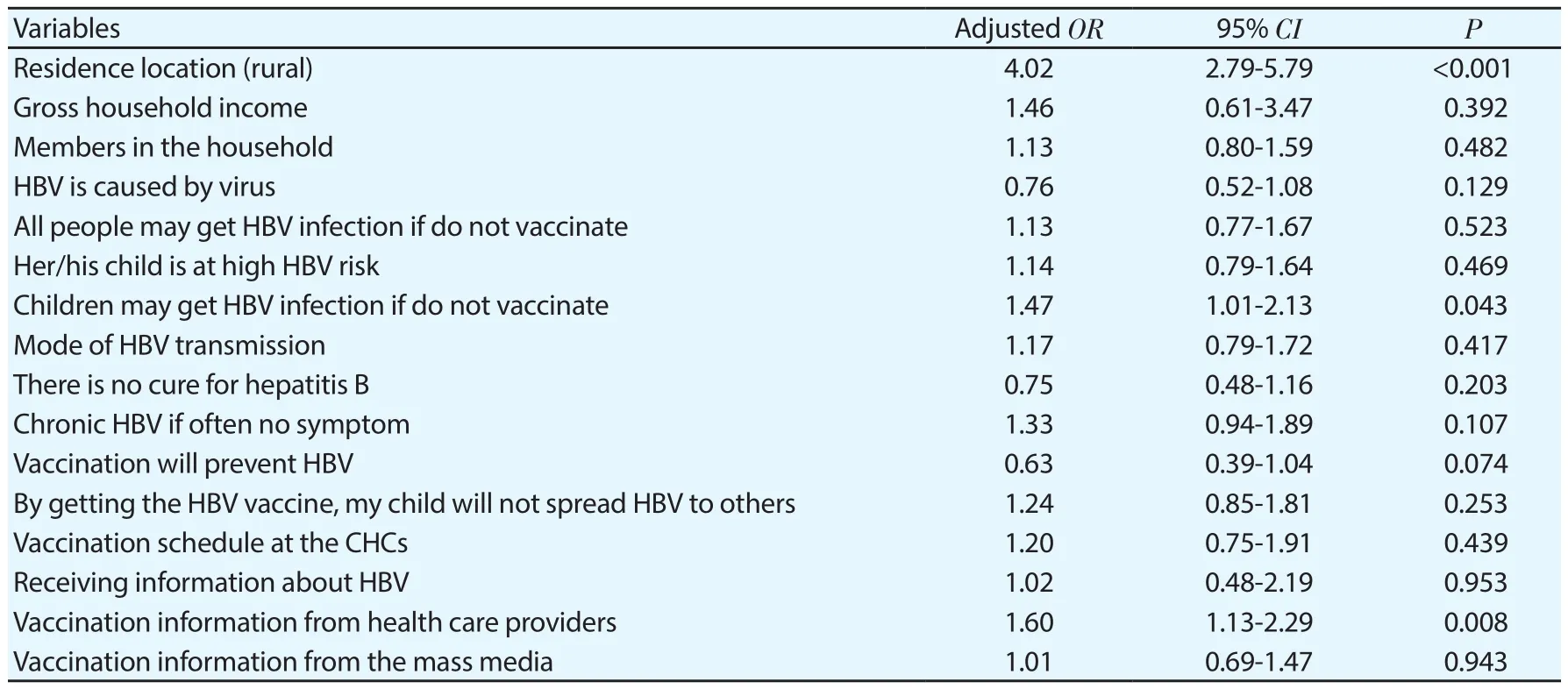

There was an association between HBV vaccination status of children and parents’ knowledge about HBV infection. We also found a statistically significant relationship between full and timely HBV vaccination with parent’s knowledge, such as the risk of contracting HBV if their children did not receive the vaccination, HBV infection was serious and chronic, HBV infection was often asymptomatic(P all <0.05) (Table 3). Logistic regression analysis indicated that children who received complete and timely HBV vaccination were significantly more likely to live in rural areas (Adjusted OR 4.02,95% CI 2.79-5.79, P<0.001). Also, children whose parents received vaccination information from health care providers, and had knowledge about HBV risk, had a higher rate of full and timely HBV vaccination(Adjusted OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.13-2.29, and Adjusted OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.01-2.13, P all<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3. Percentages of respondents answering “Yes” to the knowledge of HBV stratified by Vaccination Status of Children (N=768).

Table 4. Results of logistic regression-Determinants of full and timely hepatitis B vaccination practice (N=768).

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge of HBV disease by HBM framework

Our research developed a questionnaire based on HBM in order to ensure its content. We assessed the internal consistency of instruments through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was restricted to the range of 0 to 1. Some researchers consider values under 0.70 but close to 0.60 as satisfactory[18,19]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of our study was acceptable and are consistent with previous studies among Vietnamese Americans[15]. The questionnaire in many previous studies in Vietnam regarding the mothers’ knowledge about HBV were not based on the theoretical framework and no studies mentioned how to build questionnaires,as well as their validity and reliability. The parents in our study had moderate knowledge (7.0 items correct out of 11), compared to those in Vu LH’s study among 443 Vietnamese and 442 Chinese Australia[20]. One interesting finding was that only 40.4 % of our study participants reported knowledge about HBV transmission by mother to child during birth. The results were the same as those of Chinese Americans (39.9%)[21]and were lower than Vietnamese and Chinese Australia (67% and 76%, respectively)[20]. Recently,we have found that many mothers had misconceptions about HBV infection and hepatitis B vaccine, which included over half of the mothers (51.4%) were unaware that HBV could be transmitted during childbirth[16]. A possible explanation for this might be that the low rate of the birth dose in the past years in Vietnam[1].

Another important finding was that we found there were many misconceptions in relation to the modes of transmission, such as genetic inheritance, sharing food/plates and toothbrushes, accounting for over 20% in our study while the previous researches among other populations showed higher results. For example, more than twothirds of Malaysian HBV patients (76.8% and 87.8%, respectively)were worried about spreading HBV by sharing toothbrushes and casual contacting[22]. Due to sharing food/plates were also reported among 60.0% Chinese and 67% of Vietnamese[21,23], and 22.9% of Vietnamese mothers of children under one year in Ho Chi Minh City[16]. In general, therefore, it seems that making a stigma between individuals and HBV lead to a barrier in their social interaction with HBV infected patients. This is an important issue for future research that the educational campaigns need to reflect in the fact of the parents’ experience, and focused on the knowledge of HBV transmission. In terms of perceived severity, only 42.8% of parents knew that chronic HBV can be asymptomatic, it was likely for those who were Chinese immigrants in Cotler SJ’s study[24].Additionally, the majority of participants knew HBV was serious and lead to cancer and death 83.5% and 75.8%, respectively. The results were slightly less than those of Malaysia patients (85.1% and 78.5%, respectively)[22]. The most interesting finding was that most of the parents had correct knowledge about the benefits of vaccination that was also reported in Vietnamese Americans (94.7% and 94.4%, respectively)[21]. One unanticipated finding was that barriers found 67.2% of parents were afraid of serious side effects of the vaccination, the results seem to be consistent with the previous studies among mothers in Ho Chi Minh City and Vietnamese American[15,16]. Further research should be undertaken to investigate the efforts in the community education so emphasize the lifelong impact of HBV, its mode of transmission, especially from mother to child during birth and the positive outcomes that were obtained by vaccination, contemporaneously need to inform that the side effects of HBV vaccine have hardly happened.

4.2. Association between sample characteristics, parents’knowledge and HBV vaccination

Our result found that a low rate of parents neither delayed nor refused vaccination (33.9%) based on the vaccination card. It showed parents who lived in rural areas neither delayed nor refused vaccination for their children at a higher rate than those who lived in urban areas (Adjusted OR 4.02, 95% CI 2.79-5.79, P<0.001).This has also been confirmed in our previous study[17], and a similar finding was obtained in a study by Smith, in which children whose parents had neither delayed nor refused vaccination were 1.5 times more likely to live in rural areas (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0-2.4, P<0.05)[25]. In addition, our study found that the group of parents who received vaccination information from health staff did have a statistically significant difference compared to the group that did not. This result was similar to Bigham’s and our previous studies that the HBV immunization was significantly associated with a recommendation for HBV vaccination from a health care professional[14,17]. Therefore, health workers played an important role in community health education. Besides, knowledge of HBV disease included children’s parents who knew that children may get HBV infection if they did not vaccinate, were associated with full and timely vaccination practices. Therefore, health information distribution needs to be done regularly by the health workers at CHCs, it should inform parents that all people are susceptible to HBV and their children could get HBV if they do not receive the complete vaccination program as stated. Some limitations should be considered when we collected information from parents/caregivers who had the vaccination cards as well as attended immunization at CHCs in Ho Chi Minh City, therefore, the findings may be not representative for all parents/caregivers and children who were living in different regions in Vietnam.

In conclusion, there were much incorrect knowledge, identified,about HBV among parents. Furthermore full and timely HBV vaccination was associated with the residential location and the total knowledge score of the participant. Therefore, more health education from health workers should target parents living in specific locations and focus on the benefit of the HBV vaccine.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the support of the nurses at the Commune Health Centers (CHCs) in Ho Chi Minh City who facilitated the study. We thank all the families for the time and effort that they devoted to the study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors substantially contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. HG, PLA, and BQV designed the study, acquisition of the data, managed the analyses of the study. TTT and CNN managed the literature searches, HG and NTNH were the contributors to the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2021年3期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2021年3期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Genotype 4 reassortant Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine flu virus: An emerging public health challenge

- SARS-CoV-2 may impair pancreatic function via basigin: A single-cell transcriptomic study of the pancreas

- Burkholderia pseudomallei infection manifests as mediastinal/hilar lymphadenopathy:A case report

- In vitro anti-plasmodial activity of new synthetic derivatives of 1-(heteroaryl)-2-((5-nitroheteroaryl)methylene) hydrazine

- Prevalence and intensity of soil-transmitted helminth infections among school-age children in the Cagayan Valley, the Philippines

- Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in animals in Iran: A systematic review and metaanalysis