Utilisation of smoking cessation aids among South African adult smokers: findings from a national survey of 18 208 South African adults

Israel Agaku, Catherine Egbe, Olalekan Ayo- Yusuf

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

During 2016, 21.5% of South African adults smoked ciga—rettes.1About 20% of deaths from pulmonary tubercu—losis, and 8% of all deaths in South Africa are attributable to smoking.23Several of the 10 leading causes of death in South Africa (eg, tuberculosis, pneumonia, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertensive disease and chronic respiratory disease) are caused, exacerbated or associated with smoking.245Quitting smoking reduces the risk for smoking— related morbidity and mortality. While several cessation aids exist in South Africa, including the national quit— line (011 720 3145) and clinical resources (eg, pharmacotherapy and cessa—tion counselling), the limited evidence to date reveals gaps in access and utilisation.67Only 29.3% of South African smokers received healthcare professional advice to quit smoking during 2012.8South Africa has progres—sively passed several policies over the past few decades to encourage smoking cessation.9—12However, smoking cessation medications are not included in the essential medicines list for South Africa, and therefore, all asso—ciated costs for these medications must be paid out— of— pocket, a challenge for individuals of low socioeconomic position.13—15Data are needed, not only on what smokers are using to quit smoking (ie, cessation aids), but also why smokers are trying to quit (ie, cessation triggers), as this could inform public health policies, programmes and practice.

The Health Belief Model provides an appropriate frame—work through which to examine and address smoking cessation interventions in South Africa.16Applied to smoking cessation, this psychosocial model suggests that smokers will attempt to quit if they perceive themselves to be susceptible to smoking— attributable morbidity or mortality (eg, because of an underlying health condi—tion or a health scare), and believe that the benefits of smoking cessation (health and/or economic) outweigh any perceived downsides (eg, diminished smoking sensory experience). Other components of the model have some implications for clinical and public health practitioners. For example, cues to action may include advice or assis—tance from a healthcare provider to motivate quitting. Such cues may also include comprehensive smoke— free policies and other population— level educational interven—tions that have been demonstrated in previous research to be associated with quitting behaviour.4Perceived self— efficacy (belief in being able to quit successfully) is a very important component of the model as it offers insights into the smoker’s current stage of change (precontem—plation, contemplation, action, maintenance),17and may also have implications for usage of evidence— based cessation aids.18For example, smokers who are not confi—dent of their ability to quit successfully cold turkey may be more inclined to use smoking cessation aids as part of their quit attempt.

To better understand these issues within the South African context, this study analysed a large sample of current combustible tobacco smokers to assess use of cessation aids as well as demographic and psychographic correlates of cessation behaviour. Specific research ques—tions were as follows: (1) What percentage of current combustible smokers have ever attempted to quit during their lifetime, and what types of cessation aids have they ever used? (2) What are barriers to smoking cessation among current combustible smokers who have never attempted to quit during their lifetime? A better under—standing of these issues is important for comprehensive tobacco prevention and control activities in South Africa.

METHODS

Data sources

This was a cross— sectional, web— based survey of South African adults aged ≥18 years conducted in July 2018 (n=18 208). Online participants were recruited from the national consumer database for News24—South Afri—ca’s largest digital publisher. As an incentive, consenting participants were eligible for a raffle draw prize of R5000 for completing the survey. Survey completion rates among eligible individuals who clicked on the email invi—tations was 75.3% (20 383/27 087, online supplemental figure 1). For our main analyses, the denominator was current smokers of any combustible tobacco product (ie, cigarettes, cigars, pipes or roll— your— own (RYO) cigarettes; n=5657), who indicated they had not quit smoking at the time of the survey and smoked every day, some days, or rarely.

Measures

Current combustible tobacco use

Current combustible tobacco smokers (n=5657) were defined as individuals who self— identified as being a regular user of any ‘smoke or smokeless’ product in general and reported using at least one combustible tobacco product at the time of the survey at any frequency (cigarettes, pipes, cigars and RYO tobacco). Those who answered ‘used but stopped’ to all of the combustible tobacco products assessed were excluded from the analyses.

Quitting intentions, behaviours, attitudes and cessation aids

Smokers were classified as having no quit intention if they indicated: ‘I’ve never tried to quit and don’t want to’ or ‘I’ve tried before and failed, so why try again?’ A past quit attempt was defined as a report by a smoker that they had made ≥one quit attempt in their lifetime, regardless of success. Participants were classified as having success—fully quit within the past year if they answered ‘less than a month’; ‘1—6 months’ or ‘6—12 months’ to the question ‘How long ago did you quit smoking?’ Triggers for past quit attempts (among those who had ever tried to quit) as well as potential/perceived triggers for future quit attempts (among those who had never tried to quit) were also assessed.

We were interested in past use of evidence— based cessa—tion aids (among those who had ever tried to quit) as well as planned use (among those with quit intentions). The full list of response options for each assessed item in terms of ever or current use status was ‘never heard of’; ‘heard of, never used’, ‘use rarely/once off’, ‘use regularly’ and ‘used but stopped’. Usage, both ever (‘use rarely/once off’, ‘use regularly’ and ‘used but stopped’) and current (‘use rarely/once off’, ‘use regularly’), was determined for the following cessation aids: (1) ‘nicotine sprays’ (eg, Quit); (2) ‘nicotine gums’ (eg, Nicorette); (3) ‘pharmaceutical medication to stop smoking’ (eg, Zyban, Champix); (4) ‘smoking cessation programmes’ (eg, SmokEnders, Allan Carr) (ie, cessation counselling programmes). Responses (1) or (2) were classified as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Responses (1), (2) or (3) were classified as any medication. Any of aids (1) through (4) was classified as having used any cessation aid. Smokers were classified as being aware of each of the above interventions if they had ever used it, or ‘heard of, (but) never used’. Planned use of cessation aids was ascertained for ‘if/when (respondents) were ready to quit smoking; those answering ‘I would rely on willpower’ were classified as intending to quit cold turkey. Inveterate smokers were defined as current combustible smokers who had never made a quit attempt in their lifetime and had no intention to quit smoking.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics

These included race/ethnicity, gender, age, monthly personal income and self— rated health status.

Analyses

Calibration weights were developed using raking (itera—tive proportional fitting); population marginal distribu—tions on the weighting variables were derived from the 2017 South African census projections (ie, reference population). Weighting was done using three adjustment variables: age, gender and race/ethnicity. Percentages and bootstrapped CIs were calculated for descriptive analyses; non— overlap of CIs was used, along with X2tests, to determine whether prevalence estimates were significantly different from each other. Bootstrapping, a non— parametric approach, was used to compute CIs for prevalence estimates in the absence of non— probability— based sampling. Because of the large amount of descrip—tive data, we minimised the number of statistical subgroup comparisons to avoid type I statistical error. Instead, infer—ences regarding global differences were largely made conservatively based on presence or absence of overlap of the computed 95% CIs. Logistic regression analyses were used to explore correlates of reporting specific quit triggers among those who had made a past quit attempt; predictor variables assessed were race/ethnicity, gender, age, monthly personal income, self— rated health status and age at smoking initiation. We also modelled quit attempt as a function of reported reason for smoking behaviour, controlling for aforementioned independent variables. Statistical significance was assessed at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with R V.3.6.1.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

The inherent limitations of the web survey in terms of potential measurement and selection biases led us to conduct sensitivity analyses to determine how certain key measures from the weighted analyses compared with those from a nationally representative household survey of South African adults—the 2017 South African Social Attitudes Surveys (SASAS). We compared the following indicators that were present in both surveys: (1) preva—lence of current any tobacco use and of current cigarette smoking; (2) percentage of smokers who made a quit attempt (lifetime quit attempt assessed in web survey vs past year quit attempt in SASAS) and (3) percentage of those who made a quit attempt that used any cessation aid.

RESULTS

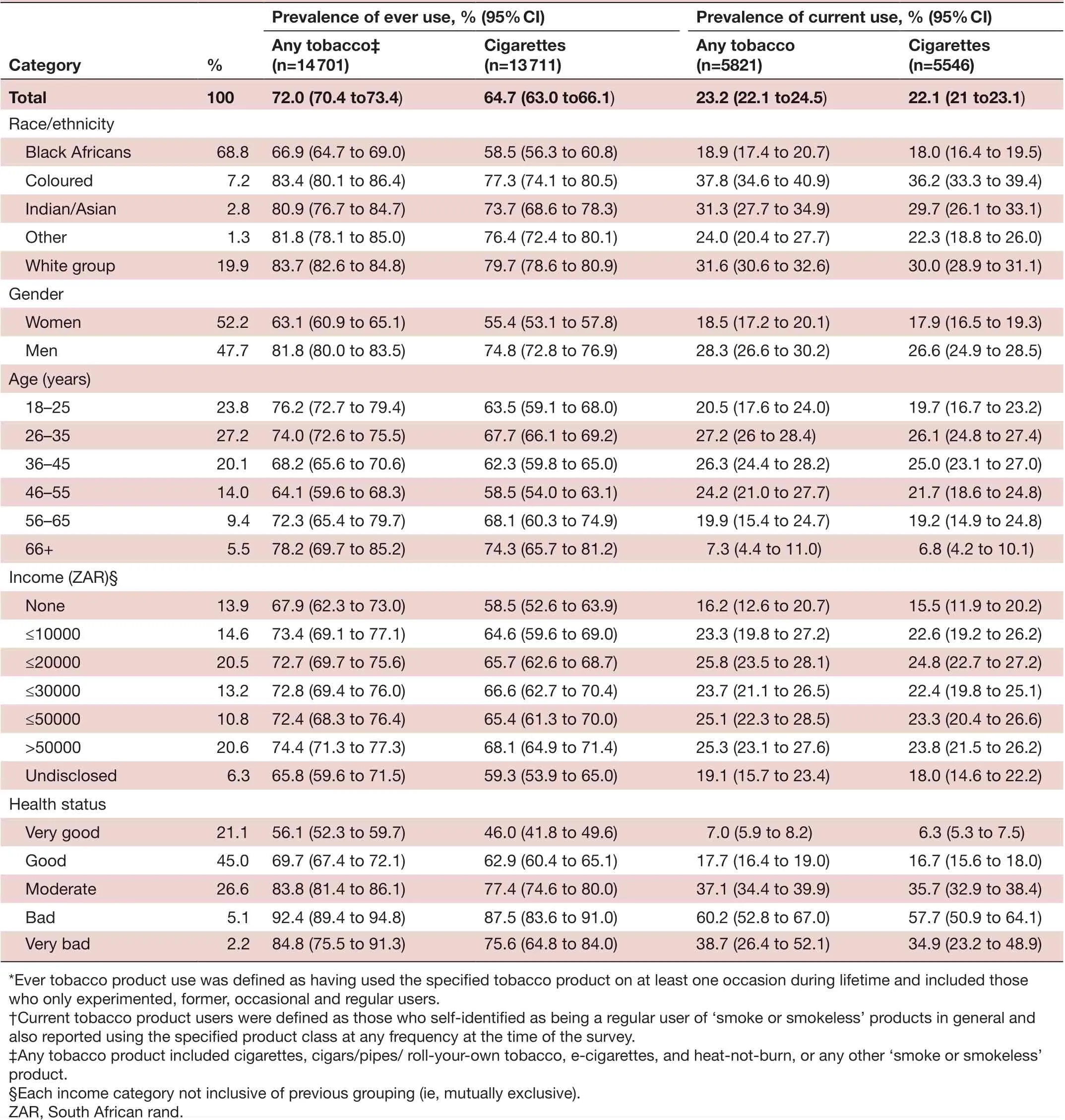

Weighted distributions among all respondents overall revealed that most individuals (68.8%) were Black Afri—cans and women (52.2%). Other demographic charac—teristics are available in table 1. Overall, 72.0% of the population reported ever use prevalence of at least one tobacco product. Current use prevalence was as follows: any tobacco product (23.2%); any combustible tobacco product (22.4%) and cigarettes (22.1%); (table 1). Overall, 98.7% of current smokers of any combustible tobacco were current cigarette smokers.

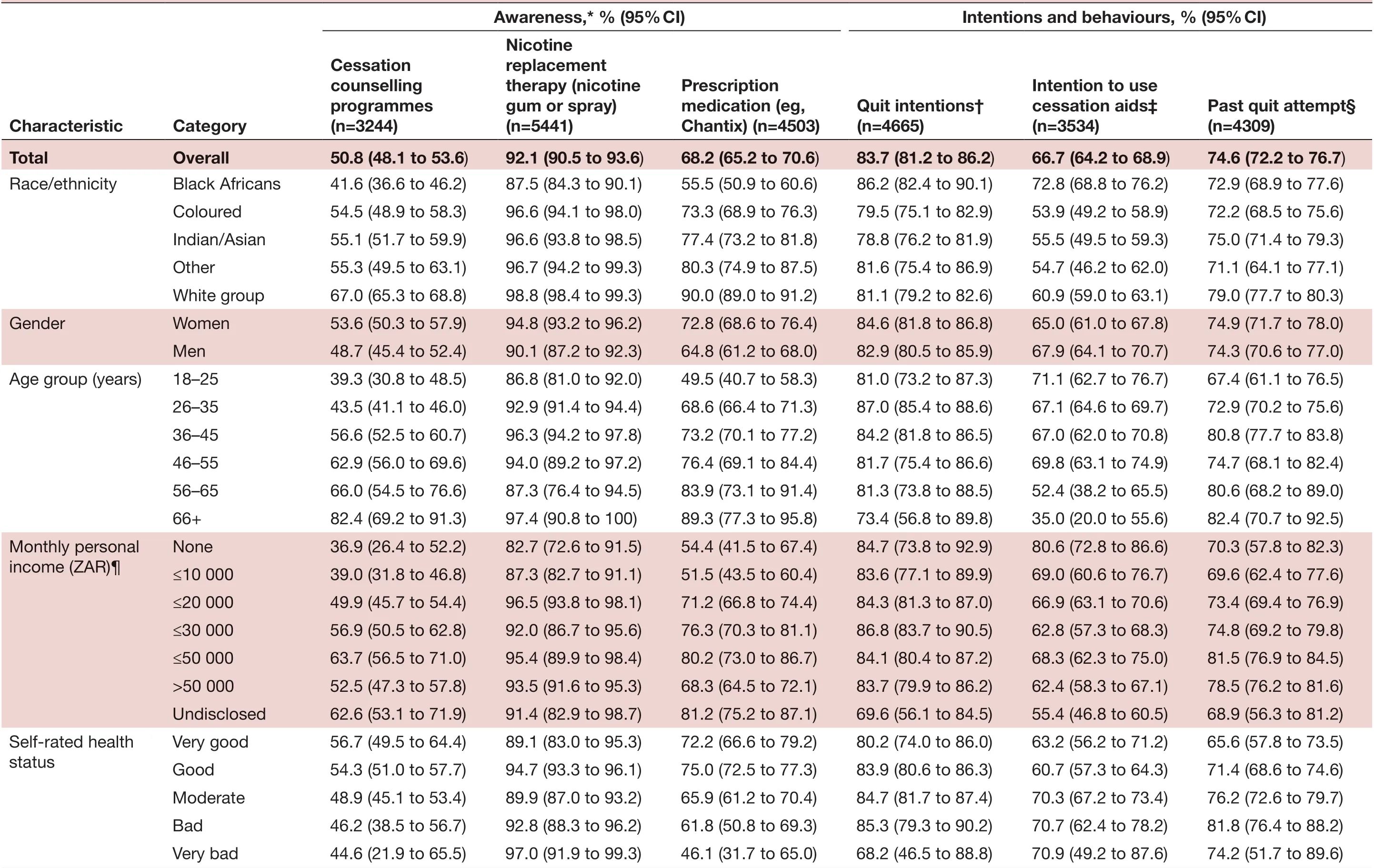

Significant differences in tobacco use prevalence were seen among all demographic groups assessed, as evidenced from non— overlap of CIs in table 1. Awareness of cessation aids was as follows among current combus—tible smokers: smoking cessation programmes, 50.8%; NRT, 92.1%; prescription cessation medication, 68.2%. Awareness of cessation aids was lowest among Black Afri—cans, men, and persons with little or no income (table 2).

Differences in cessation behaviours and attitudes by demographic characteristics

A past quit attempt was reported by 74.6% of all current combustible smokers (table 2). The proportion reporting a past quit attempt was highest and lowest among the following groups (all p<0.05): white group (79.0%) versus other race (71.1%); persons’ aged ≥66 years (82.4%) versus 18—25 years (67.4%); those earning monthly income of R30 001—50 000 (81.5%) versus undisclosed income (68.9%); and those reporting ‘bad’ (81.8%) versus ‘very good’ health (65.6%).

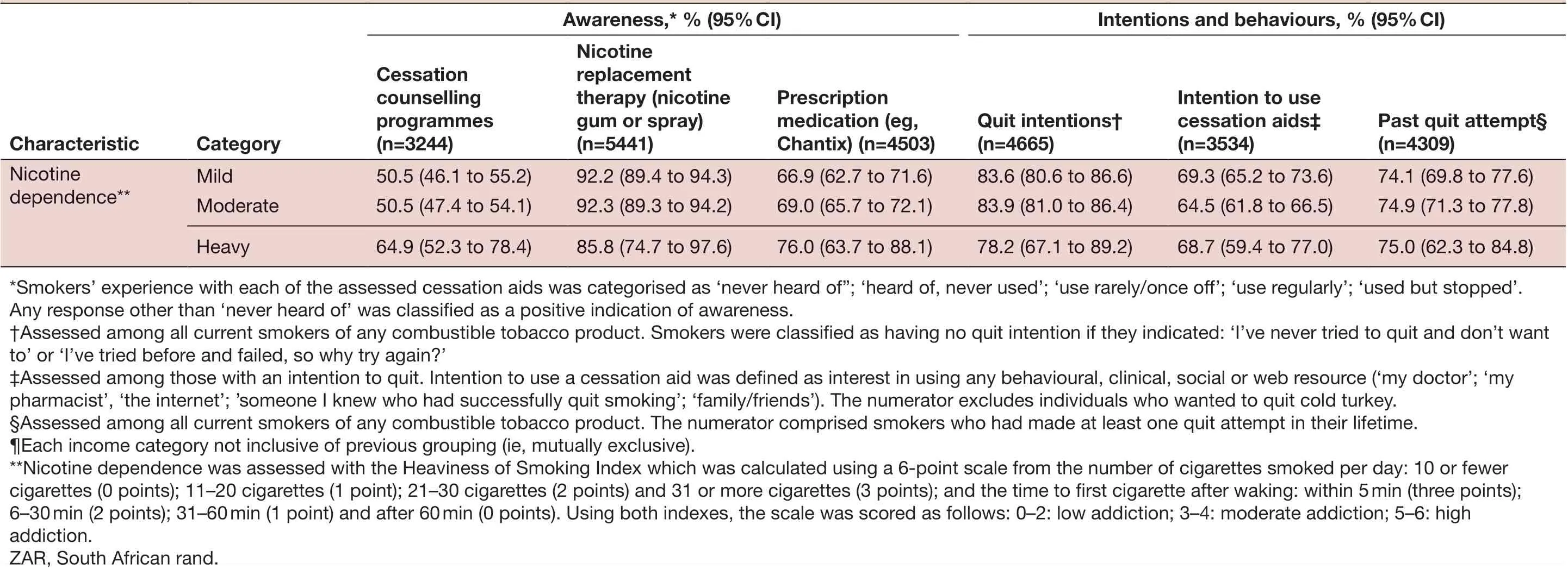

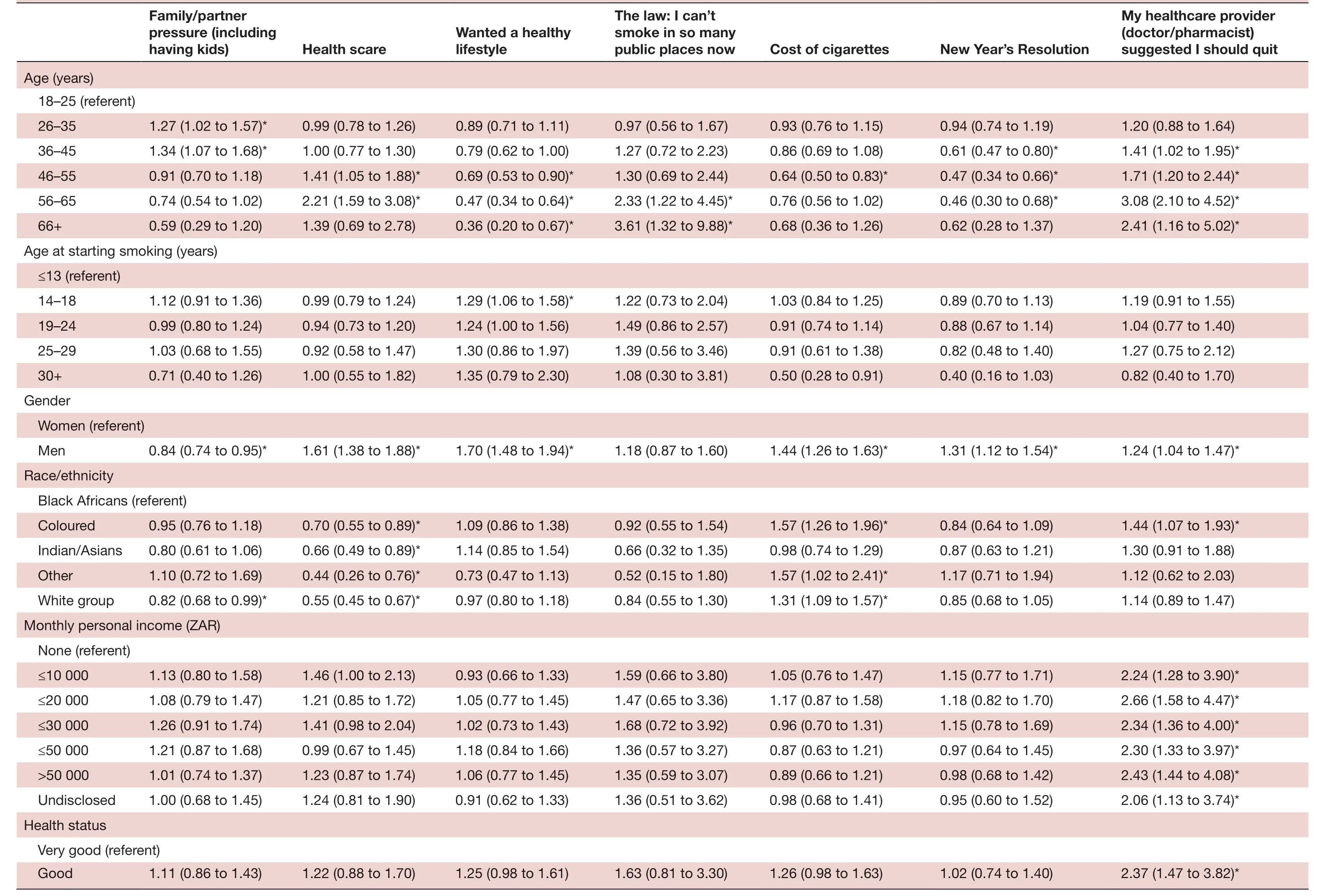

Factors triggering a quit attempt also varied by subgroups (table 3). Men were less likely than womento attempt to quit because of family/partner pressure, including having kids (adjusted OR (AOR)=0.84), but more likely to attempt following advice from a health professional (AOR=1.24); a New Year’s Resolution (AOR=1.31); increasing cost of cigarettes (AOR=1.44); a health scare (AOR=1.61) and desire for a healthier lifestyle (AOR=1.70). Compared with Black Africans, all other race/ethnic groups had lower odds of attempting to quit because of a health scare but were all more likely (except Indians/Asians) to quit because of increasing cost of cigarettes. Interestingly, income status was not inde—pendently associated with having made a quit attempt because of increasing cost of cigarettes; it was however associated with attempting to quit on account of advice from a health professional. Smokers with suboptimal self— rated health reported higher odds of attempting to quit following advice from a health professional or after a health scare, compared with those reporting ‘very good’ health. Compared with those aged 18—25 years, the odds of attempting to quit because of public smoking banswere higher among those aged 56—65 years (AOR=2.33) and ≥66 years (AOR=3.61) (all p<0.05). Older adults aged 56—65 years were also more likely to attempt to quit after a specific health scare incident (AOR=2.21), but less likely to attempt out of a general desire to maintain a healthy lifestyle (AOR=0.47) (all p<0.05).

Table 1 Ever* and current? use of tobacco products among South African adults, 2018 (n=18 208)

Table 2 Awareness, intentions and behaviours of South African smokers in relation to smoking cessation among current smokers of any combustible tobacco product, 2018 (n=5657)

Continued

Table 2 Continued

Continued

Table 3 Correlates of specifci quit triggers among current smokers of any combustible tobacco product who have made a past quit attempt in their lifetime, South Africa, 2018 (n=4309)

My healthcare provider (doctor/pharmacist) suggested I should quit 3.59 (2.24 to 5.77)*6.11 (3.66 to 10.20)*6.72 (3.49 to 12.91)*New Year’s Resolution 1.18 (0.86 to 1.62)0.90 (0.60 to 1.33)0.58 (0.29 to 1.17)Cost of cigarettes 1.26 (0.98 to 1.63)1.34 (0.98 to 1.82)0.83 (0.50 to 1.38)The law: I can’t smoke in so many public places now 1.70 (0.84 to 3.45)1.63 (0.71 to 3.71)2.73 (0.97 to 7.68)Wanted a healthy lifestyle 1.58 (1.23 to 2.04)*2.07 (1.50 to 2.86)*1.20 (0.74 to 1.96)Health scare 2.28 (1.65 to 3.17)*3.18 (2.19 to 4.61)*4.12 (2.43 to 6.98)*Family/partner pressure (including having kids)1.11 (0.85 to 1.43)1.05 (0.77 to 1.44)0.88 (0.53 to 1.45) Moderate Bad Very bad*Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance at p<0.05.ZAR, South African rand.

Use of different cessation aids among current combus—tible smokers who made a past quit attempt was as follows (table 4): any medication (ever use, 40.0%; current use, 28.0 %); counselling (ever use, 9.8%; current use, 7.1%); any cessation aid, that is, pharmacotherapy and/or coun—selling (ever use, 42.8%; current use, 31.0%). Online supplemental figure 2 shows the prevalence of ever use of different cessation aids among those who quit in the past year. Disparities existed in use of cessation aids among current combustible smokers who made a past quit attempt; current use of any cessation aid among white group (45.7%) was almost twofold higher than among Black Africans (24.6%) or coloured (24.3%). Similarly, current use of any cessation aid among those earning R30 001—50 000 monthly (46.1%) was approximately fourfold higher than those with no income (12.2%).

Of current combustible smokers intending to quit, 66.7% indicated interest in using a cessation aid for future quitting and only 33.3% wanted to quit cold turkey. By specific aids, 24.7% of those planning to use any cessa—tion aid were interested in getting help from a pharma—cist, 44.6% from a doctor, 49.8% from someone who had successfully quit, 30.0% from a family member and 26.5% from web resources. Past use of any cessation aid was a determinant of planned use (AOR=1.67, p<0.05). Demo—graphic variations in planned and past utilisation of cessa—tion aids are highlighted in tables 2 and 4, respectively. Of all current combustible smokers regardless of past quit attempt, 27.1% reported current use of a smoking cessa—tion aid.

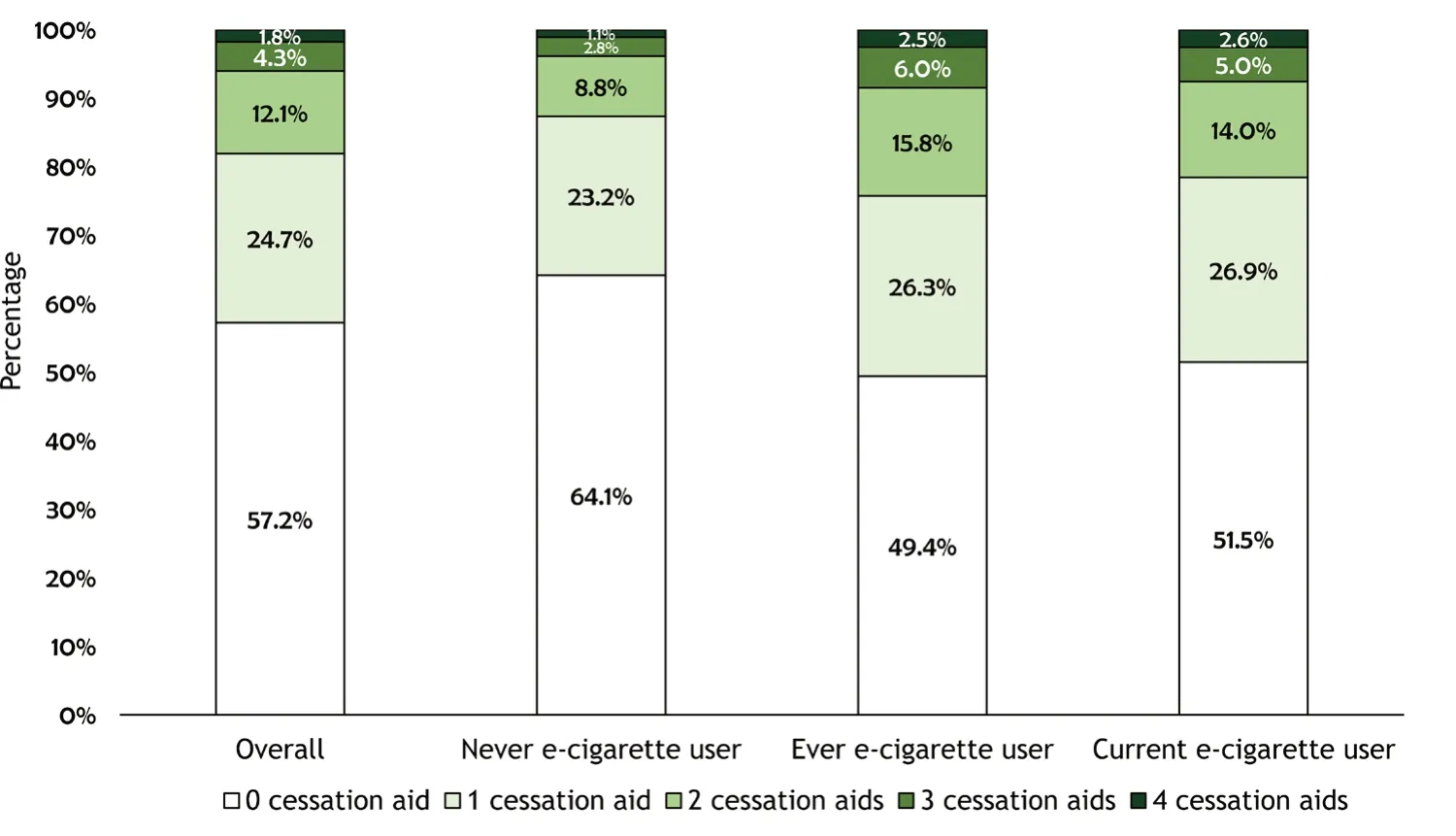

Differences in cessation behaviours and attitudes by psychographic and other tobacco-use characteristics

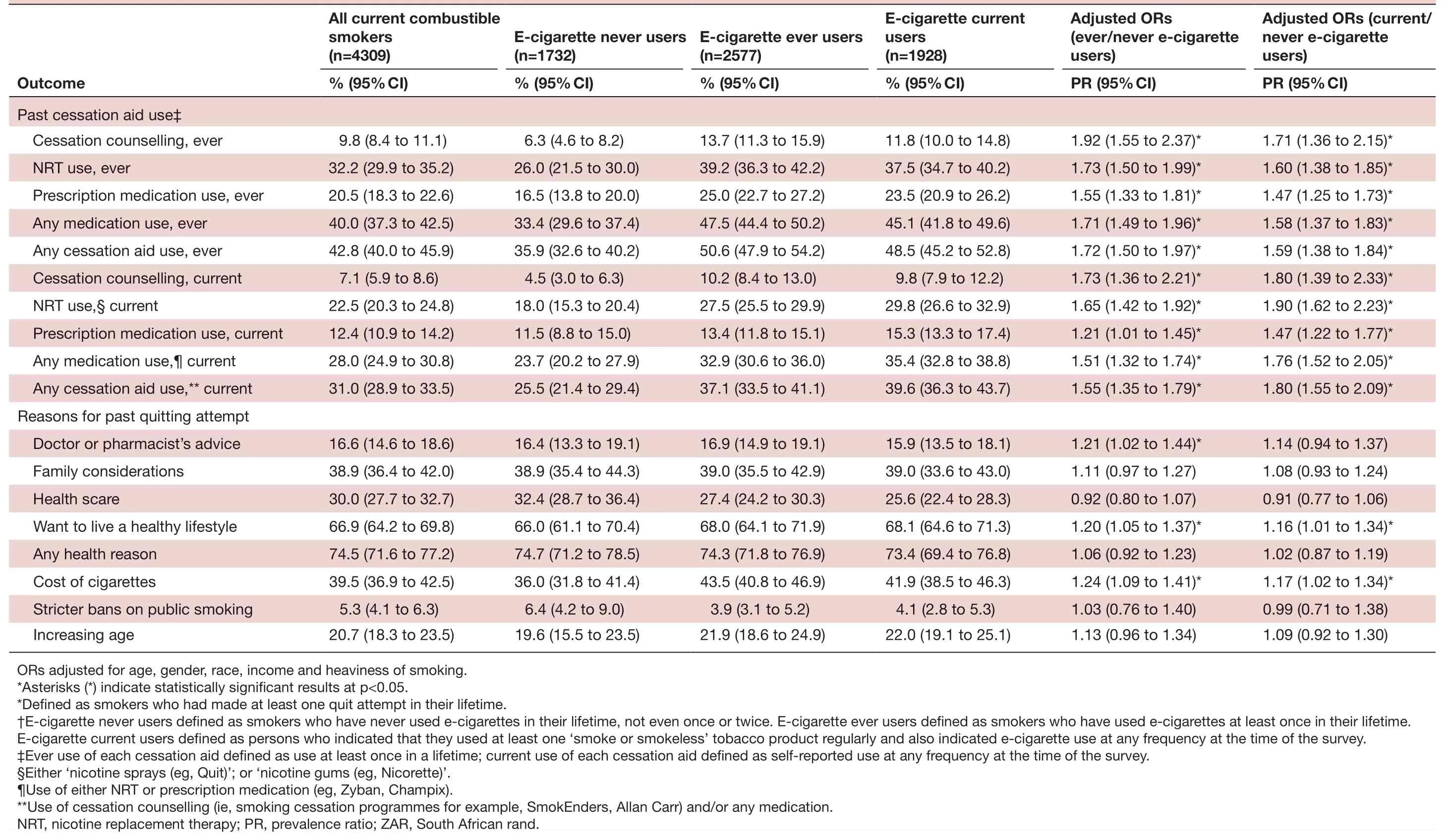

Among current combustible smokers who had made a quit attempt, ever e— cigarette users were more likely than never e— cigarette users to have ever used cessation counselling (AOR=1.92; 95% CI=1.55 to 2.37); NRT (AOR=1.73; 95% CI=1.50 to 1.99); prescription medica—tion (AOR=1.55; 95% CI=1.33 to 1.81) and any cessation aid (AOR=1.72; 95% CI=1.50 to 1.97), after adjusting for age, gender, race, income and heaviness of smoking. Among current combustible smokers, ever and current e— cigarette users were also more likely to report current use of cessation aids at the time of the survey (table 5). Figure 1 compares the number of different cessation aids ever used of the four specific aids assessed: nicotine patch, nicotine spray, prescription medication and cessation counselling. The results showed that among e— cigarette never users, the percentages that reported ever use of 0, 1, 2, 3 or all 4 cessation aids were 64.1%, 23.2%, 8.8%, 2.8% and 1.1%, respectively; the corresponding percent—ages among e— cigarette ever users were 49.4%, 26.3%,15.8%, 6.0% and 2.5% (p<0.05). Among all ever e— cig—arette users, 43.5% were current combustible tobacco smokers; of current e— cigarette users, 97.5% were current combustible tobacco smokers.

Table 4 Ever and current use of cessation aids among South African current combustible tobacco smokers who have made a past quit attempt, 2018 (n=4309)

Continued

Table 5 Smoking cessation behaviours and attitudes among South African current combustible tobacco smokers who made a past quit attempt,* by e- cigarette use status,? 2018 (n=4309)

Figure 1 Number of distinct cessation aids ever used by current combustible smokers who had made a quit attempt, overall and by e- cigarette use status. Denominator was smokers who had tried to quit at least once in their lifetime. Ever use of the assessed cessation aids was defined as use of the specified cessation aid at least once in a lifetime. Four distinct cessation aids were assessed including ‘nicotine sprays (eg, Quit)’; ‘nicotine gums (eg, Nicorette)’; ‘pharmaceutical medication to stop smoking (eg, Zyban, Champix)’ and ‘smoking cessation programmes (eg, SmokEnders, Allan Carr)’. E- cigarette never users defined as smokers who have never used e- cigarettes in their lifetime, not even once or twice. E- cigarette ever users defined as smokers who have used e- cigarettes at least once in their lifetime. E- cigarette current users defined as persons who indicated that they used at least one ‘smoke or smokeless’ tobacco product regularly and also indicated e- cigarette use at any frequency at the time of the survey.

Among current combustible smokers, increasing cost of cigarettes predicted an attempt to quit cigarette smoking among e— cigarette ever versus never users (AOR=1.24; 95% CI=1.09 to 1.41). E— cigarette ever users were also more likely to attempt to quit smoking cigarettes because of advice from a doctor or pharmacist (AOR=1.21; 95% CI=1.02 to 1.44).

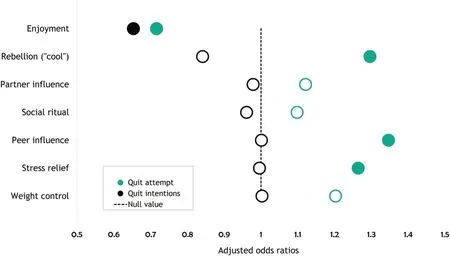

Figure 2 Reason for smoking as a predictor of past quit attempts and future quit intentions among current smokers of combustible tobacco products. Note: solid=statistically significant; hollow=non- significant. ORs were computed adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, self- rated health status and nicotine- dependence status. Quit attempters were smokers who had made at least one quit attempt in their lifetime. Smokers were classified as not having a quit intention if they indicated: ‘I’ve never tried to quit and don’t want to’ or ‘I’ve tried before and failed, so why try again?’

Figure 3 Actual triggers of a past quit attempt among current combustible tobacco smokers who have attempted to quit, as well as potential (perceived) triggers among those who have never tried to quit. Health reasons among those who tried to quit include ‘health scare’ or ‘wanted a healthy lifestyle’. The response options analysed as ‘increasing age’ were slightly different for ever quit attempters (‘New Year’s Resolution’) versus never quit attempters (‘when I am older’).

Among current combustible smokers overall, reasons for smoking predicted quit attempts (figure 2). The odds of making a quit attempt were higher among those who smoked to relieve stress (AOR=1.26); because they thought it was ‘cool’ (AOR=1.30) or because of peer pressure (AOR=1.35) (all p<0.05). Conversely, those who smoked because they enjoyed the smoking experience had lower odds of making a quit attempt (AOR=0.72) or intending to quit smoking (AOR=0.65) (all p<0.05). Reasons cited for smoking relapse included quitting is hard (56.9%), smoking is enjoyable (34.1%), low self— efficacy in quitting successfully (13.8%) or the perception that smoking is safe (1.2%). Similarly, the most commonly cited reason for having never made a quit attempt was that it is too hard to quit (57.1%) followed by enjoyment of smoking (49.2%); 4.4% had never attempted to quit because they perceived smoking to be safe.

Among those who had never tried to quit smoking, inveterate smokers—comprising 6.1% of all current combustible smokers—differed from other non— attempters who otherwise had a quit intention in some respects (figure 3). Inveterate smokers were less likely to consider comprehensive smoke— free laws (3.7% vs 23.7%) or increasing cost of cigarettes (15.6% vs 27.0%) as things that could ever make them consider quitting (all p<0.05). No significant differences were observed by other factors.

Results of sensitivity analyses

The indicators compared between the web— based and the household— based surveys of South African adults showed very similar findings within weighted analyses (online supplemental figure 3). For example, current use of any tobacco product was 24.6% in the 2017 SASAS versus 23.2% in the web survey. Slightly wider differences were observed in quit attempts (60.6% for SASAS vs 74.6% in the web survey), consistent with differences in case defi—nition (past year quit attempts for SASAS vs lifetime quit attempts in the web survey).

DISCUSSION

Awareness of cessation aids among current combustible smokers varied by type of cessation aid: smoking cessation programmes, 50.8%; prescription cessation medication, 68.2% and NRT, 92.1%. Awareness of cessation aids was lowest among Black Africans, men and persons with little or no income. Of all current combustible smokers, 74.6% had ever attempted to quit and 42.8% of these quit attempters had ever used any cessation aid. Among past quit attempters, ever e— cigarette users were more likely than never e— cigarette users to have ever used any cessa—tion aid (50.6% vs 35.9%, p<0.05). Of current combus—tible smokers intending to quit, 66.7% indicated interest in using a cessation aid for future quitting and only 33.3% wanted to quit cold turkey.

Despite high awareness of cessation aids among South African smokers, utilisation was low. Awareness and use were much lower for cessation counselling programmes and for prescription medications compared with NRT, possibly because of the ubiquitous display of NRT at retail outlets. Most NRT formulations, including oral spray and inhaler, can be purchased in South Africa as over— the— counter medication within pharmacies, super—markets or online. However, as our findings revealed, low— income smokers may face severe limitations in accessing these medications. A complete regimen of nicotine patch lasting up to 12 weeks long, one patch per day, for a heavy smoker (10+ cigarettes), could cost between R9070 ($605) and R21 580 ($1438), based on current retail prices in South Africa and recommended usage.15Including drugs for nicotine— dependence treatment on the South African Essential Drugs list,1314and expanding coverage for smoking cessation treatment within the National Health Insurance19may increase access and utilisation of evidence— based cessation aids among South African smokers.

Current utilisation rates for cessation aids in our study were very similar to those reported in the USA, including for cessation counselling (7.1% vs 6.8%), any medi—cation use (28.0% vs 29.0%) and use of any cessation aid (31.0% vs 31.2%, South Africa vs the USA, respec—tively).20The pattern of disparities in access and use of cessation aids by socioeconomic status is also consistent with those reported elsewhere.621In our study, Black Africans reported greater interest in using cessation aids and higher intentions to quit, but reported lower past use of cessation aids, suggesting that the gap in utilisa—tion of cessation aids is largely driven by differences in socioeconomic status, rather than differences in interest or motivation. Increasing delivery of brief cessation counselling within all clinical settings (including public health facilities that serve low— income groups), as called for in Article 14 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,22can help smokers quit and improve their health.2324In addition, enhancing the effective—ness of clinical smoking cessation services (eg, the 5As) can help increase cessation. For example, our findings suggest that asking smokers the reason why they smoke could be potentially useful in assessing their willingness to quit. Certain life— changing moments, such as the diag—nosis of a serious condition associated with, or exacer—bated by smoking (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) can be leveraged to provide counselling and motivate quitting.25Our results showed that a health scare was associated with quitting, especially among those with poor health conditions. Notably, older adults were less likely to make a quit attempt just for maintaining a healthy lifestyle but were more likely to do so on account of a health scare.

South Africa has not officially adopted tobacco harm reduction, however, some in the public health commu—nity have argued for the effectiveness of this strategy among ‘inveterate’ smokers who are unwilling or unable to quit.26The potential viability of a harm reduction approach, from a public health context, however rests on assumptions that: (1) there is a large pool of invet—erate smokers; (2) that these smokers will be interested in switching to, and exclusively using ‘reduced— risk’ prod—ucts which would help them quit; and (3) that a regu—lated climate exists to prevent unwanted consequences among youth. Our findings however disprove several of these assumptions within the South African context. Only about 6% of current combustible smokers were consid—ered ‘inveterate’, and even these were open to quitting for health reasons (50%), family considerations (29%), increasing age (24%) and increasing costs of cigarettes (15.6%).

As the tobacco market and regulatory landscapes in South Africa continue to evolve rapidly, regula—tion of novel products is critical to minimise potential population— level harms, including relapse and perpetu—ation of smoking behaviour among smokers. Deeming and regulating e— cigarettes as tobacco products under the proposed legislation may benefit public health,1127not only in South Africa, but regionally as well, given the leadership role South Africa plays in the region. These findings can help inform comprehensive tobacco preven—tion and control efforts, including restricting unsubstanti—ated marketing claims of e— cigarettes as effective smoking cessation aids within South Africa.

Socioeconomic status was not a significant predictor of quitting on account of ‘increasing cigarette cost’, possibly because of the use of price— minimising strategies by smokers, including buying cheap brands, single sticks or switching to cheaper RYO cigarettes.2829Policies that address cross— product price inequalities can help reduce demand and use of tobacco products.30We also found that older adults, who had the lowest smoking preva—lence, were the only demographic group to attempt to quit smoking in response to public bans on smoking, suggesting limited compliance. Stronger enforcement of policies that prohibit smoking in public places may prevent relapse by reducing social cues and denormal—ising smoking.3132

More robust epidemiological studies that address threats to internal validity are needed to test some of the hypothesis generated from our study. For example, our results suggested that claims of e— cigarettes being effective cessation aids may be probably overstated in the South African context, given the observation that smokers who used e— cigarettes were more likely than non— e— cigarette users to have used other cessation aids. Clinical or real— world effectiveness trials are needed to evaluate the inde—pendent effect of e— cigarettes on smoking cessation in South Africa.

This study is not without limitations. First, it is impos—sible to determine temporality with the cross— sectional design (eg, order of using e— cigarettes and evidence— based cessation aids). Second, triggers of past quit attempt could have varied for individuals with multiple quit attempts as could also the types of cessation aids used. Third, the self— reported measures are subject to misreporting. Finally, despite the use of calibration weights, the weighted sample may still not be entirely representative of the South African adult population because adjustments were only made for a few variables for which information was available in the dataset. We however found that compar—ison of results with 2017 SASAS, a household— based survey, yielded similar results on assessed indicators.

CONCLUSION

Most smokers were interested in quitting, but only about one— third of smokers who had tried to quit had ever used any cessation aid; NRT was the most used cessation aid. Disparities existed in the use of any cessation aid, with utilisation being least among Black Africans and indi—viduals of low socioeconomic position. Smokers who tried to quit and used e— cigarettes reported higher use of pharmacological cessation aids and counselling than non— e— cigarette users. Intensified implementation of comprehensive tobacco prevention and control strat—egies that include barrier— free access to cessation aids, price increases on tobacco products, comprehensive smoke— free laws and mass media educational campaigns that warn of the dangers of tobacco use may accelerate cessation rates among South African adults.

ContributorsIA conceptualised and designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript. CE and OA- Y helped conceptualise the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingThe African Capacity Building Foundation Grant number 333.

Competing interestsNone declared.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Ethics approvalThe study was approved by the University of Pretoria’s Faculty of Health Sciences’ Ethics Review (no. 39/2019).

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementRequests for data should be sent to the corresponding author and will be considered on a case- by- case basis.

Supplemental materialThis content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer- reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年1期

Family Medicine and Community Health2021年1期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Medical use and misuse of psychoactive prescription medications among US youth and young adults

- Comparison of self- report and objective measures of male sexual dysfunction in a Japanese primary care setting: a cross- sectional, self- administered mixed methods survey

- Are we Athens or Florence? COVID-19 in historical context