Contrast-enhanced ultrasound using SonoVue mixed with oral gastrointestinal contrast agent to evaluate esophageal hiatal hernia:Report of three cases and a literature review

Jing-Yu Wang, Yan Luo, Wen-Ying Wang, Shi-Cheng Zheng, Lian He, Chun-Yan Xie, Li Peng

Jing-Yu Wang, Wen-Ying Wang, Lian He, Li Peng, Department of Ultrasound, First People's Hospital of Longquanyi District, Longquan Hospital of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610100, Sichuan Province, China

Yan Luo, Department of Ultrasound, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

Shi-Cheng Zheng, Chun-Yan Xie, Department of Gastroenterology, First People's Hospital of Longquanyi District, Longquan Hospital of West China Hospital of Sichuan University,Chengdu 610100, Sichuan Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Due to a thicker abdominal wall in some patients, ultrasound artifacts from gastrointestinal gas and surrounding tissues can interfere with routine ultrasound examination, precluding its ability to display or clearly show the structure of a hernial sac (HS) and thereby diminishing diagnostic performance for esophageal hiatal hernia (EHH). Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) imaging using an oral agent mixture allows for clear and intuitive identification of an EHH sac and dynamic observation of esophageal reflux.CASE SUMMARY In this case series, we report three patients with clinically-suspected EHH,including two females and one male with an average age of 67.3 ± 16.4 years.CEUS was administered with an oral agent mixture (microbubble-based SonoVue and gastrointestinal contrast agent) and identified a direct sign of supradiaphragmatic HS (containing the hyperechoic agent) and indirect signs [e.g., widening of esophageal hiatus, hyperechoic mixture agent continuously or intermittently reflux flowing back and forth from the stomach into the supradiaphragmatic HS, and esophagus-gastric echo ring (i.e., the “EG” ring) seen above the diaphragm]. All three cases received a definitive diagnosis of EHH by esophageal manometry and gastroscopy. Two lesions resolved upon drug treatment and one required surgery. The recurrence rate in follow-up was 0%. The data from these cases suggest that the new non-invasive examination method may greatly improve the diagnosis of EHH.CONCLUSION CEUS with the oral agent mixture can facilitate clear and intuitive identification of HS and dynamic observation of esophageal reflux.

Key Words: SonoVue; Oral gastrointestinal contrast agent; Contrast-enhanced ultrasound;Gastrointestinal; Hiatal hernia; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

Esophageal hiatal hernia (EHH) refers to one or more abdominal organs entering the mediastinum through the esophageal hiatus[1]. Clinically, the condition is divided into four types, namely, sliding type (type I), paraesophageal type (type II), mixed type(type III), and multiple organ type (type IV)[2,3]. The overall incidence is about 10%-50%[2], and type I is the most common form, accounting for more than 85% of overall cases[1]. Clinically, diagnostic methods for EHH include radiography, endoscopy,esophageal manometry[4], pH measurement[3], and ultrasonography[5]. However, each of these techniques has shortcomings and limitations, such as radiation exposure,more invasiveness, difficulty in finding small and sliding hernias, and inconclusive diagnosis for small EHH. Previous studies have showed that real-time ultrasound is effective for evaluating EHH, when used with an oral contrast agent that fills the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, thereby allowing for observation of a hernial sac (HS)[6,7].Unfortunately, due to a thicker abdominal wall in some patients, the interference of ultrasound artifacts (from GI gases and surrounding tissues) and the small size of an HS can obscure the oral contrast ultrasound image, precluding display or clear visualization of the HS structure and diminishing diagnostic performance for EHH.

In order to find an effective and reliable diagnostic method to more accurately and easily evaluate EHH, we generated an oral agent mixture to investigate the performance of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and to demonstrate the characteristic ultrasound manifestations of EHH in this study.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

All patients in this case series presented with clinically-suspected EHH requiring treatment.

History of present illness

Case 1:A 63-year-old woman presented to the gastroenterology department of our hospital, complaining of a half-year history of belching, acid reflux, and pain behind the sternum.

Case 2:A 46-year-old man presented with complaints of a 1-year history of heartburn,acid reflux, and feeling of gastric fullness.

Case 3:A 78-year-old woman presented with complaints of a 1-year history of heartburn, acid reflux, pain behind the sternum, and belching.

History of past illness

Case 1:The patient reported that her symptoms had previously been treated as gastritis, but she had experienced no significant improvement.

Case 2:The patient had no significant medical history.

Case 3:The patient had an established diagnosis of hypertension, for which she was taking antihypertensive medications.

Imaging examinations

Oral contrast agent mixture preparation and optimization:A mixed oral contrast suspension was created by mixing microbubble-based SonoVue with a GI contrast agent. First, a vial (59 mg) of SonoVue (Bracco, Milan, Italy) was diluted with 5 mL saline and shaken well to formulate into a microbubble suspension. Second, one package (50 g) of oral GI contrast agent (Tianxia; Huzhou East Asia Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Huzhou, China) was mixed with 500 mL boiling water (100 °C) and stirred evenly, after which it was cooled to room temperature naturally.

To optimize the oral contrast agent mixture, different ratios of SonoVue were mixed with the GI contrast agent (i.e., 1 mL:500 mL, 2.5 mL:500 mL, and 5 mL:500 mL) and then tested in three normal volunteers. Each of the three mixture suspensions was administrated orally, after which the volunteer underwent CEUS of the upper GI tract.The results of CEUS with the different mixture ratios of the tested agent were judged subjectively by two experienced ultrasound doctors (Wang JY and Peng L, each with more than 20 years of ultrasound experience) for selecting the optimal mixture ratio of the agent.

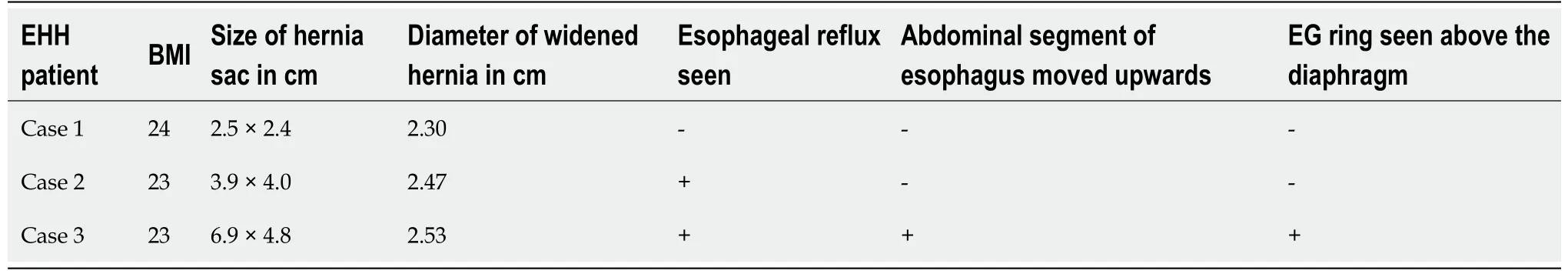

Real-time CEUS demonstrated that, for all ratios, the mixed suspension agent appeared as hyperechoic content and entered from the esophagus into the gastric cavity (Figure 1). The optimal mixed oral contrast agent ratio was determined to be the 2.5 mL:500 mL mixture, and was applied to all three of the EHH patients reported herein (Table 1).

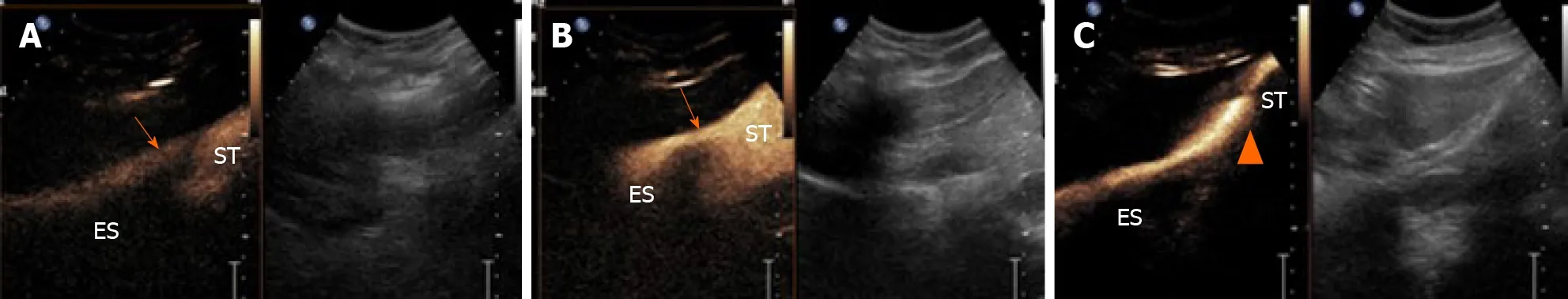

Ultrasound scanning was performed in two stages, using the conventional oral contrast agent and the new oral agent mixture. We observed dynamically lower esophageal segment and hiatus, cardia, and gastric fundus and body during the swallowing of the agent. At the same time, we performed measurements of the esophageal hiatus and the HS (Figure 2).

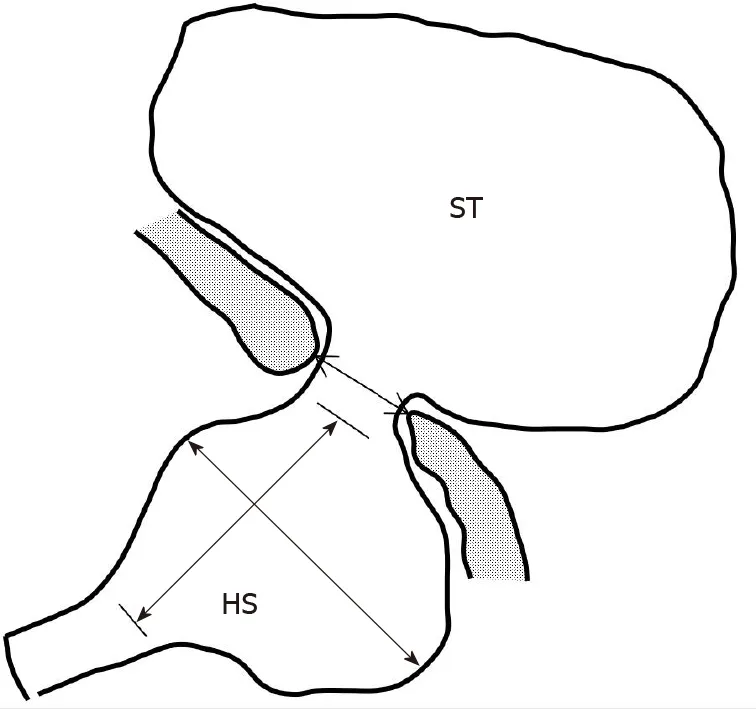

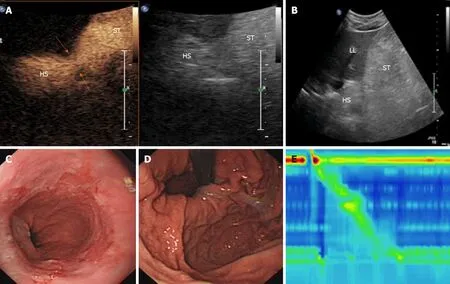

Case 1:Gray-scale ultrasound measurement of the esophageal hiatus was 2.2 cm on an empty stomach and 2.3 cm after drinking the oral contrast agent mixture. CEUS clearly identified a hyperechoic HS, located above the diaphragm and measuring 2.5 cm × 2.4 cm (Figure 3A and B). The ultrasound diagnosis of EHH was confirmed by gastroscopy, and definitively diagnosed as EHH (Figure 3C and D).

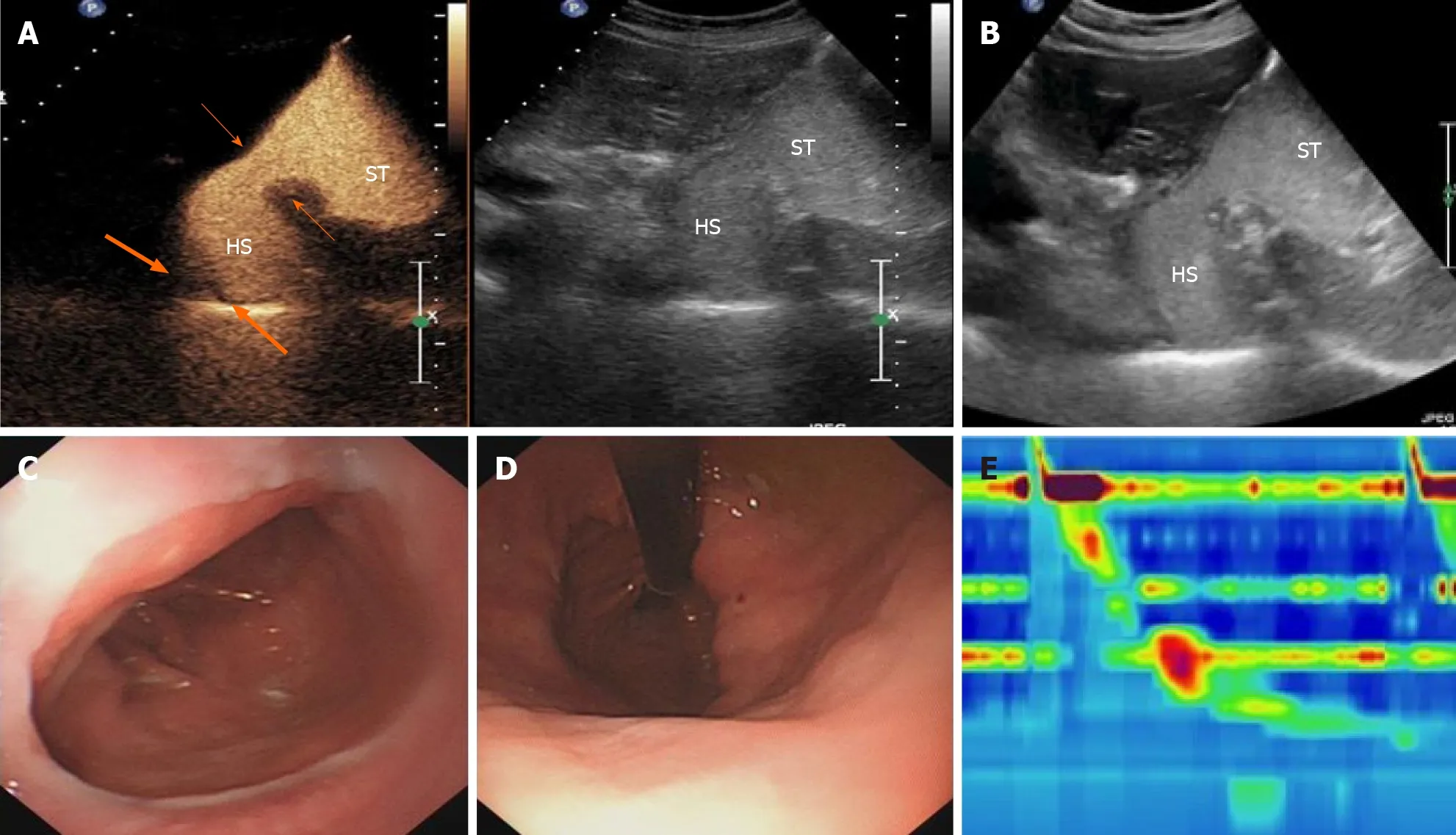

Case 2:Gray-scale ultrasound measurement of the esophageal hiatus was 1.5 cm on an empty stomach and 1.64 cm after drinking the oral contrast agent mixture. The contrast-filled HS was located above the diaphragm, measuring 3.9 cm × 4.0 cm(Figure 4A and B). Real-time ultrasound imaging showed the hyperechoic contrast agent being refluxed into the supradiaphragmatic HS from the gastric cavity, at the rate of about three times in 5 min; the total reflux time lasted > 3 s. The ultrasound diagnosis was EHH with gastroesophageal reflux, which was consistent with gastroscopy results (Figure 4C and D). High-resolution esophageal pressure measurement showed that the upper esophageal sphincter pressure was normal with normal relaxation, while the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure was low(Figure 4E).

Case 3:Gray-scale ultrasound measurement of the esophageal hiatus was 2.22 cm on an empty stomach and 2.53 cm after drinking the oral contrast agent mixture. Theabdominal segment of the esophagus moved upwards and the contrast-filled HS was found above the diaphragm, measuring 6.9 cm × 4.8 cm and having the characteristic esophagus-gastric echo ring (i.e., the “EG” ring) (Figure 5A and B). Real-time ultrasound imaging showed the hyperechoic contrast agent being refluxed into the supradiaphragmatic HS from the gastric cavity, at the rate of about three times in 5 min; the total reflux time lasted > 3 s. The ultrasound diagnosis was EHH with gastroesophageal reflux, which was consistent with gastroscopy results (Figure 5C and D). High-resolution esophageal pressure measurement showed that the upper esophageal sphincter pressure was normal with abnormal relaxation, while the LES pressure was low and associated with separation of the LES from the diaphragm,which was consistent with a type III EHH (Figure 5E).

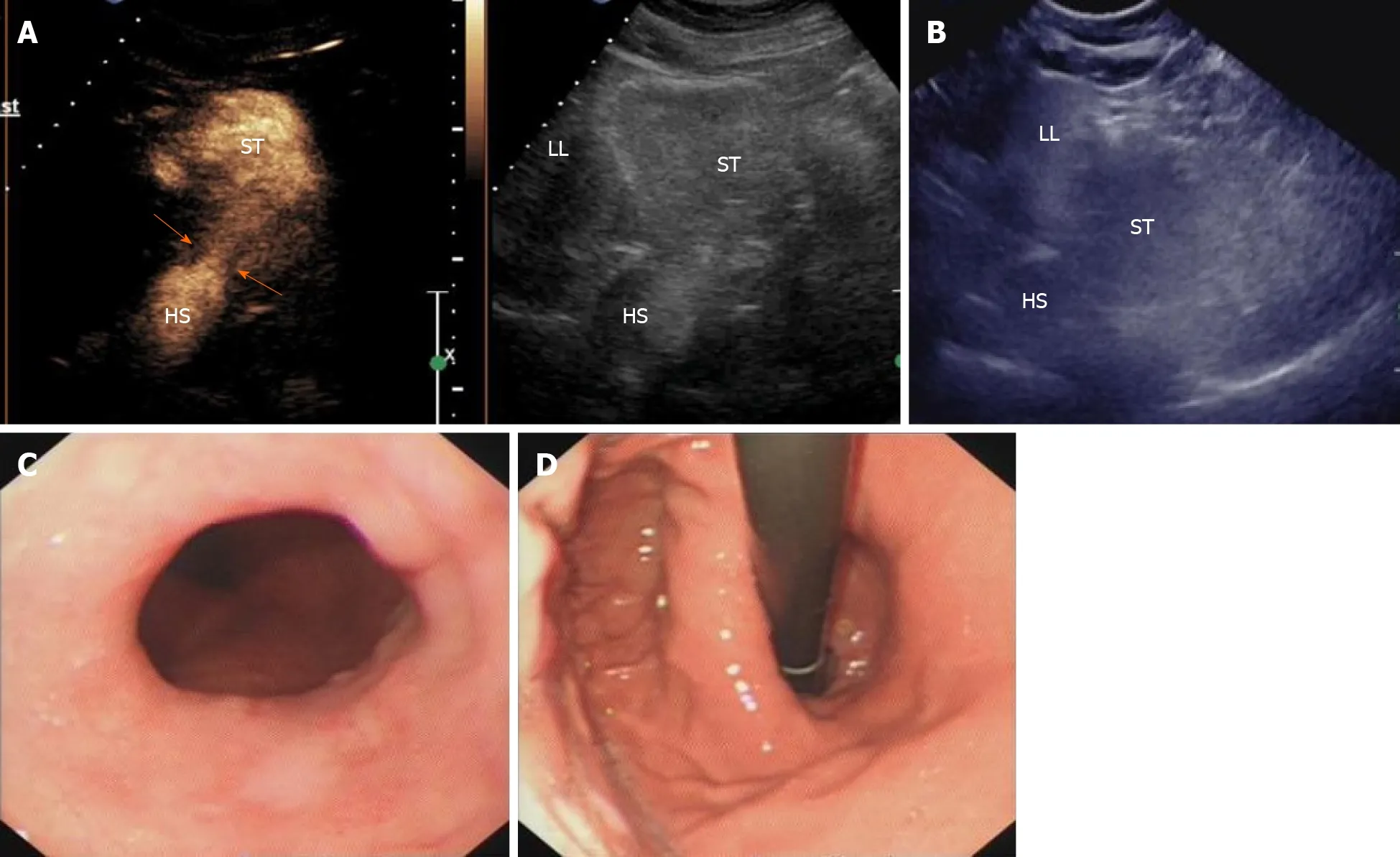

Table 1 Contrast ultrasound manifestations in three esophageal hiatal hernia patients

Figure 1 Optimization of the contrast agent mixture in normal volunteers. A: Gray-scale and contrast-enhanced ultrasound showed mild and insufficient enhancement of the upper gastrointestinal tract at the mixture ratio of 1 mL:500 mL; B: The 2.5 mL:500 mL ratio mixture produced homogenous moderate enhancement with good sound penetrability and margin delineation appearing within the esophagus and stomach. Arrows indicate the esophageal hiatus; C: The 5 mL:500 mL ratio mixture produced strong enhancement reflection with obvious far-field sound attenuation (triangle). ES: Esophagus; ST: Stomach.

Figure 2 Measurement of the esophageal hiatus and the hernial sac. The schematic diagram shows the measurement of the esophageal hiatus with fine-head arrows and the hernial sac with solid-head arrows. HS: Hernial sac; ST: Stomach.

Figure 3 A 63-year-old woman with esophageal hiatal hernia. A: Compared to the gray-scale imaging (right panel), contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging clearly showed the esophageal hiatus (arrows) and the supradiaphragmatic hernial sac (HS); B: Ultrasound image obtained with conventional oral contrast agent shows the HS; C: Gastroscopic front view showed the dentate line to be shifted upwards and separated from the gastroesophageal junction; D: In the reverse view,the cardia opening was shown to be loosened and the double ring sign was partially visible. HS: Hernial sac; LL: Left liver lobe; ST: Stomach.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1: EHH.

Cases 2 and 3:EHH with gastroesophageal reflux.

TREATMENT

Cases 1 and 2 were administrated standard drug treatment. Case 3 underwent surgery.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1:Ultrasound showed that the HS was still present at half a year after the diagnosis, although the patient's symptoms had disappeared.

Case 2:Ultrasound showed that the HS was still present at 1 year after the diagnosis,although the patient's symptoms had disappeared.

Case 3:During the 1-year follow-up period, the patient's symptoms disappeared and follow-up ultrasound examination revealed no evidence of recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Figure 4 A 46-year-old man with esophageal hiatal hernia. A: Compared to the gray-scale imaging (right panel), contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging clearly showed the esophageal hiatus (arrows) and the supradiaphragmatic hernial sac (HS); B: Ultrasound image obtained with conventional oral contrast agent shows the HS; C: Gastroscopic front view showed the reflux esophagitis; D: In the reverse view, the cardia opening was shown to be loosened; E: High-resolution esophageal pressure measurement showed type II esophageal hiatal hernia. HS: Hernial sac; LL: Left liver lobe; ST: Stomach.

Esophageal hiatus is commonly formed by a division of the right diaphragmatic foot into two branches around the esophagus[8]. A study pointed out that all EHH patients with esophageal hiatus had hiatus widening and the shape of the hiatus changed from sagittal foramen to circular foramen[8]. In addition, a previous study has shown that the incidence and prevalence of EHH increase with the patient's age and body mass index[9]. The underlying reasons are that the elasticity of the ligament structure around the diaphragm hiatus decreases with age and that the gastric pressure increase in obese patients leads to an increase in the axial pressure of the esophagus at the opening of the diaphragm. The clinical symptoms of EHH can correspondingly include upper abdomen or retrosternal pain, heartburn, acid reflux, postprandial satiety, nausea, retching, and dysphagia[8]. In addition, due to the destruction of the anti-reflux mechanism between supradiaphragmatic HS and the cardia, patients with EHH often have coexistent gastroesophageal reflux[3,10]. The acid exposure of the esophagus causes contraction of the longitudinal muscles of the esophagus.Furthermore, the esophagus undergoes axial shortening and the cardia becomes pulled upwards[3]. The frequent reflux itself will lead to more esophageal acid exposure and further aggravate the damage and contraction of the esophagus, thus forming a vicious circle.

It has been a long-standing consensus that gas in the lungs and GI tract limits the application of ultrasound in the diagnosis of GI diseases. In fact, this started as early as when Naik and Moore[11]first used ultrasound to observe the gastroesophageal junction, and was agreed upon by the subsequent researchers[12]expanding the scope of ultrasound examination to the upper digestive tract in children. Westraet al[5]used ultrasound to observe the structural morphology of the gastroesophageal junction in children for the first time and measured the angle between the esophagus and the fundus of the stomach and abdominal esophagus, describing and summarizing the ultrasound characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux and EHH in infants. In recent years, with the rapid development of ultrasound technology and the application of oral GI contrast agents[13-15], the application of ultrasound in the GI tract has spread rapidly. However, in the case of patients with a thicker abdominal wall, interference by lung gas and surrounding tissues has led to poorer ultrasound image quality,greatly affecting the doctor's ability to observe and determine differential diagnoses.

Figure 5 A 78-year-old woman with esophageal hiatal hernia. A: Compared to the gray-scale imaging (right panel), contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging clearly showed the esophageal hiatus (large arrows), the supradiaphragmatic hernial sac (HS), and esophagus-gastric echo ring (i.e., the “EG” ring) (small arrows); B:Ultrasound image obtained with conventional oral contrast agent showed the HS; C: Gastroscopic front view showed the dentate line to be shifted upwards and separated from the gastroesophageal junction; D: In the reverse view, the cardia opening was shown to be loosened and the double ring sign was partially visible; E:High-resolution esophageal pressure measurement showed type III esophageal hiatal hernia. HS: Hernial sac; ST: Stomach.

With advancement of the CEUS technique in recent years, the abilities of ultrasound-based diagnosis have been greatly improved. The second-generation ultrasound enhancer SonoVue is a microbubble-based enhancer used to produce a hyperechogenic reflection on contrast harmonic ultrasound imaging for vascular and nonvascular applications[16-21]. For the diagnosis of GI diseases, it was reported that adding the contrast agent SHU 508 A (Levovist; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) to milk was useful for ultrasound diagnosis and classification of gastroesophageal reflux in children[10]. Other scholars have applied a mixture of SonoVue with an oral GI agent for positioning of a naso-intestinal tube in critically ill patients[22]. The oral GI contrast agent Tianxia is a commercially available product in China and has been used to fill the stomach, replacing gastric gas and debris, for GI ultrasound examination[6,23-27]. This powder-based agent is made from edible grains and various natural ingredients,including rice, yam, and tangerine peel, and can reconstitute with water to form a fluid solution that appears as an echogenic reflection in the GI tract on conventional grayscale ultrasound imaging.

In the present study, we created an oral contrast agent mixture using SonoVue and the conventional oral GI agent Tianxia, in order to obtain a better enhancement effect for esophageal and gastric ultrasound examination. As far as we know, there is no report on the use of SonoVue mixed with an oral GI contrast agent in the diagnosis of EHH. The oral agent mixture and simultaneous dual-screen display were used for not just visualization of anatomic structures of esophagus and stomach as well as surrounding structures on gray-scale imaging but also for better delineation of contrast-enhanced luminal structures (i.e.,HS) and dynamic changes of the enhanced fluid on contrast imaging, which exploited the advantages of the two contrast agents.The double-screen comparison was useful for imaging and facilitated the accurate localization of the area of interest. At the same time, since noise from the surrounding tissues, such as liver, blood vessel, and heart tissues, is suppressed and the interference of surrounding air is removed on contrast mode imaging, the shape and contour of the digestive tract and cavity can be clearly outlined.

Ultrasound can not only demonstrate the morphology of the GI tract but also evaluate its function[28,29]. In the present study, we found that this oral agent mixture is helpful for CEUS imaging of EHH patients with esophageal reflux, especially for obese patients with severe gas interference. First, the mixed agent can enhance the gray-scale imaging of the oral GI contrast agent; second, the mixed solution is in a semi-liquid state and stays in the stomach for a long time, so the time and frequency of reflux can be observed continuously[6,7]. When the patient is lying on their right side and performing Valsalva maneuvers, the increase of abdominal pressure will reduce the anti-reflux mechanism, which makes it easier to observe the situation of reflux.Because some small hernias or sliding hernias are often asymptomatic or manifest atypical symptoms and intermittent episodes, they are easily interfered by subjective factors, and thus routine ultrasound, X-ray radiography, endoscopy, and esophageal manometry are not readily able to facilitate a diagnosis[30]. For such patients, CEUS with the oral agent mixture can make up for the deficiencies of these routine examinations and can be beneficial for evaluation of small hernias and sliding hernias.

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of application of CEUS with an oral agent mixture in the diagnosis of EHH. With it, we were able to identify the direct sign of EHH and the indirect signs through enhanced imaging, clearly and intuitively. The advantages of this method are ease of use, no radiation exposure, noninvasive nature,and reliability, all of which hold great value for clinical application in patients with EHH.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年11期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年11期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Endoscopic diagnosis of early-stage primary esophageal small cell carcinoma: Report of two cases

- Melatonin for an obese child with MC4R gene variant showing epilepsy and disordered sleep: A case report

- Rare histological subtype of invasive micropapillary carcinoma in the ampulla of Vater: A case report

- Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease of the temporomandibular joint invading the middle cranial fossa: Two case reports

- Surgical therapy for hemangioma of the azygos vein arch under thoracoscopy: A case report

- Cholangiojejunostomy for multiple biliary ducts in living donor liver transplantation: A case report