Leishmania donovani: Immune response and immune evasion with emphasis on PD-1/PDL-1 pathway and role of autophagy

Samar Habib, Manar Azab, Khaled Elmasry, Aya Handoussa

1Department of Medical Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

2Department of Human Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Leishmania donovani; PD-1/PDL-1; Autophagy;Immune response; Immunity

1. Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the disease caused by Leishmania(L.) donovani and is transmitted by the female sand fly. It is considered as one of the most overlooked infectious diseases owing to the large number of affected patients, poor prognosis, and problems concerning the current available therapy. It is necessary to find out new therapies because the available ones are expensive,cause side effects, and the parasite has developed resistance against them[1]. Successful immune response against leishmaniasis requires fine-tuned coordination between both the innate and the adaptive immune responses. The fate of the infection, whether recovery or progression to chronicity, depends, in part, on the ability of the protozoan to escape the immune response[2]. Leishmania inhibits T cell priming via decreasing the toll-like receptor (TLR)-2,TLR-4 mediated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-12 expression[3] and decreasing antigen presentation by antigen presenting cells (APCs)[4]. It also endorses T helper type (Th) 2 and T regulatory cells (Tregs) which preclude the intracellular parasite clearance with enhanced secretion of transforming growth factor(TGF)-β, IL-4, and IL-10[5].

The liver and spleen constitute the principal organs hosting L.donovani, however, the immune response of each organ to the infection is different. The liver displays successful immune response that leads to granuloma formation around the infected cells which protects them from reinfection. In contrast, the spleen develops immune pathological response that helps parasite persistence[6].

Programmed death (PD) 1 is expressed on T cells, while its ligand(PDL-1) is expressed on APCs. Their binding is essential for keeping the immune balance and preventing host tissue damage[7].Interestingly, several pathogens exploit this pathway to weaken the immune response and support their persistence[8]. Leishmania was reported to upregulate the PD-1/PDL-1 pathway in different models,allowing the possibility of the immune system restoration to be achieved through blocking of either PD-1 or PDL-1[9-11].

Autophagy is the recycling process which allows the cells to degrade unwanted materials in lysosomes. It is crucial for clearance of microorganisms, regulation of inflammation, and adaptive immune response[12]. Autophagy activation attenuates T cell responses, thus, several Leishmania species stimulate autophagy to evade the immune system[13-16]. Autophagy induction helps the parasite persistence and replication through supplying nutrients. It also interferes with lysosomal acidification causing less parasite degradation[17]. Recently, studies have pointed out a salient contribution of the autophagy process in the host defense against Leishmania[18,19].

2. The immune response against Leishmania

2.1. Innate immunity

Neutrophils are recruited to the site of the sand fly bite and engulf the inoculated promastigotes. They have been shown to produce various microbicidal substances such as nitric oxide (NO) and neutrophil elastase[20]. Natural killer (NK) cells participate as well,as it is the main source of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) supporting CD4T cells differentiation into Th1 phenotype[21]. It also helps direct lysis of the parasite, as well as cytotoxic mediated lysis of infected macrophages[22]. Natural killer T (NKT) cells were reported to help the clearance of the parasites in the liver of mice during the initial stages of infection via inducing IFN-γ production[23].

The complement system is concerned with destruction of promastigotes in the blood stream. Interestingly, L. donovani promastigotes, more specifically the metacyclic stages, are more resistant to complement-mediated destruction than other Leishmania species[24].

2.2. Adaptive immunity

T lymphocytes are the cornerstone factor in shaping the susceptibility or the resistance to L. donovani. The differentiation of T lymphocytes into either Th1 or Th2 will determine the immune response against Leishmania. Th1 cells provide help to macrophages by activating the intracellular killing mechanisms like inducible nitric oxide synthetase. Moreover, Th1 cells help CD8T cells in the conversion into cytotoxic T cells, causing lysis of the infected cells via granzyme B, perforin, and granulysin[25]. On the other hand,Tregs secrete immune-regulatory mediators such as IL-10, which is exploited by L. donovani to attenuate the effector functions of CD4T cells[26]. Bankoti et al.[27] stressed the detrimental role played by B lymphocyte in the persistence of L. donovani infection as they were revealed to decrease both IFN-γ expression on CD4T cells and the cytotoxic activity of Leishmania-specific CD8T cells. Additionally,Babiker et al.[28] remarked that effector cytokines such as Il-12,TNF-α, and IFN-γ versus regulatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10,and TGF-β also determine the infection outcome towards parasite clearance or persistence.

3. Immune evasion mechanisms used by L. donovani

The success of L. donovani to establish chronic infection is largely dependent on its ability to exploit and evade the host immune mechanisms. These evasion mechanisms affect various elements of the immune system including T and B lymphocytes, the complement system, macrophages, and fibroblasts.

3.1. The complement system

Sacks et al.[29] demonstrated that the infective metacyclic promastigotes develop lipophosphoglycan (LPG) elongation on its surface, which hinders the engagement of C5-C9 membrane attack complex, thus hindering the complement-mediated lysis. In addition,this infective stage of promastigotes contains higher protein kinases than other non-infective stages which phosphorylate different complement compounds, leading to inactivation of both complement pathways[30]. Moreover, Leishmania glycoprotein 63 (GP63) is highly expressed on the surface of the matacyclic promastigotes,which cleaves C3b to an inactive form, allowing Leishmania to join the complement receptor (CR) 3 on macrophages rather than CR1 leading to inhibition of IL-12 production, thus facilitating silent entry into the host cells[31].

3.2. The macrophages

3.2.1. TLRs

TLR-2 is critical for recognition of various antigens on the surface of Leishmania, particularly LPG. In optimal conditions, TLR-2 binding promotes TNF-α, IL-12, and reactive oxygen species (ROS)formation in macrophages. In order to escape this mechanism, L.donovani activates host ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20, leading to impairment of TLR-2-mediated induction of TNF-α and IL-12[32].TLR-4-mediated macrophage stimulation is also subverted by both Src homology 2 domain phosphotyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP-1)and A20, both are enhanced by over expression of TGF-β[33].

3.2.2. Survival inside phagosomal compartments

Promastigotes are phagocytized by the macrophages either directly or after phagocytosis of neutrophils recruited to the sand fly bite,they are enclosed by the phagosomes where they differentiate into amastigotes. To protect itself from the harsh conditions of the phagolysosome, Leishmania initially inhibits the fusion between the phagosome and the lysosome[34]. Leishmania not only inhibits the acidification of lysosomes through interfering with the V-ATPase pump[17], but also regulates the lysosomal trafficking proteins[35]with subsequent formation of large Parasitophorous vacuole (PV).It is essential for Leishmania containing phagosome to move along macrophage microtubule tracks towards the endolysosomal pathway,which is critical for maturation of PV, thus helping Leishmania survival and proliferation[36,37].

3.2.3. Antigen presentation

Leishmania targets antigen presentation to inhibit co-stimulation of T cells. To achieve this, the parasite sequesters antigens and interferes with loading of these antigens on the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)[38]. Interestingly, Leishmania increases the fluidity of the macrophage membrane lipid rafts where the MHC class Ⅱ should exist as microdomains, thus interfering with antigen presentation[4]. Of note, megasomes are MHC Ⅱ containing organelles which exist in the PV of parasitized macrophages. L. donovani amastigotes were reported to endocytose these organelles and degrade them[39]. Consequently, the parasite is able to evade recognition by T cell receptors.

3.2.4. Macrophages signaling

L. donovani LPG, GP63[40], and enhanced IL-10 production[41] were reported to impair protein kinase C complex, leading to the inhibition of phosphorylation of various subunits of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase complex, an essential compound in the protective mechanisms against Leishmania. Additionally, several studies have described the role of Leishmania in interrupting various signaling pathways, resulting in promoted parasite survival. For example, inhibition of JAK/STAT pathway with resulting decrease in NO production and inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway, with resultant reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, both will dampen the macrophage microbicidal functions[42].

3.2.5. Cytokines

In macrophages, pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-12, TNF-α,and IFN-γ tend to decrease while anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-13, IL-4, and IL-10 tend to increase, which support chronic infection and renders the disease difficult to control[43]. The anti-inflammatory milieu is attributed to macrophages polarization towards M2 phenotype, which was demonstrated as increase in blood arginase levels[44], decrease in NO levels[45], decrease in oxidative burst in monocytes and macrophages, and increase in levels of IL-10, CD163, and CXCL14[46].

3.3. Fibroblasts and epithelial cells

Although macrophages represent the most important host cell for Leishmania, studies have shown involvement of fibroblasts[47] and epithelial cells[48] in hosting this parasite. Bodgan et al.[49] described that following healing of a cutaneous lesion of L. major, 40% of persisting amastigotes were accumulating in fibroblasts of the draining lymph nodes. They also reported that cytokine-activated fibroblasts cannot kill L. major because of the basic inability to produce NO, therefore, these cells represent important shelter for the parasite during chronic infection. Interestingly, they found that these amastigotes inside fibroblasts are susceptible to NO produced by neighboring macrophages, creating a balance between parasite elimination and evasion in chronically infected lymph nodes.

Fibroblasts are the main source of collagen typeⅠ, which is the major component of extracellular matrix[50]. Although fibroblasts can limit Leishmania propagation in the dermis through enhancement of fibrosis, Petropolis et al.[51] described that L.amazonensis promastigotes can use collagenⅠ scaffolds to help its movement. They also remarked degradation of 20% of collagenⅠ upon invasion by Leishmania promastigotes, possibly due to metallo- and cysteine proteinases, which render the skin matrix softer, thus enabling Leishmania migration before internalization into the host macrophages. Interestingly, they noticed faster migration of Leishmania promastigotes when macrophages are present,indicating the possibility of the parasite chemotaxis by the secreted cytokines. Of note, promastigote secretory gel was stated to enhance proliferation and migration of fibroblasts in a scratch wound model[52].

3.4. T cell response

Th1 cells are critical for anti-leishmanial immune response. It provides assistance not only for the macrophages to activate NO-mediated intracellular killing but also for the CD8T cells to kill the parasites either directly or through killing of infected cells[53].Osorio et al.[54] showed that Leishmania favors switch of CD4T cells towards Th2 with subsequent anti-inflammatory cytokines production rather than the protective subset, Th1. On the other hand, Tregs are promoted by L. donovani infection, leading to the production of TGF-β and IL-10, which in turn inhibits the macrophages and Th1 responses[26]. A recent study by Kumar et al.[55] concluded that Leishmania infection induces differential microRNA expression in CD4T cells producing mixed Th1/Th2 response.

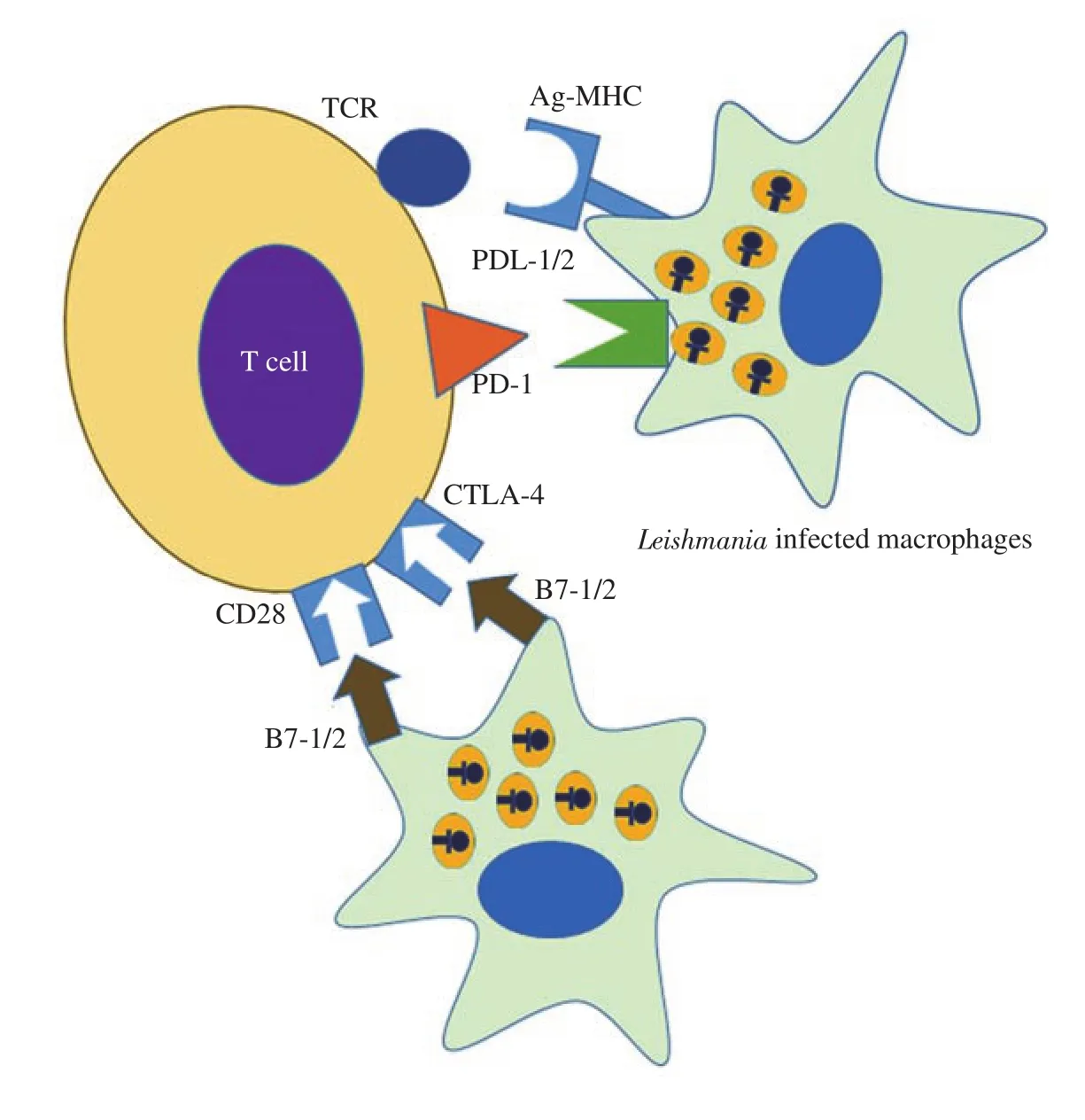

Importantly, L. donovani was reported to activate immune check points including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein(CTLA)-4 and PD-1. CTLA-4 is a co-inhibitory molecule located on T cells and engages to B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) on the APC surface with greater affinity than the co-stimulatory molecule CD28[56], while PD-1 is also located on T cell surface and engages to PDL-1 and PDL-2 on the surface of the APC[57]. As elucidated in Figure 1, over-expression by certain types of pathogens, including L. donovani, causes T cells to undergo limited clonal expansion,defective cytokine production, and enhanced apoptosis[58].

Figure 1. Immune checkpoints are upregulated during Leishmania donovani infection. For keeping self-tolerance,controlling the immune response, and reducing tissue damage, binding of Leishmania antigen-MHC Ⅱ complex which is located on antigen presenting cell (APC)to T cell receptor (TCR) that is present on T cells promotes expression of the immune check points; PD-1 and CTLA-4 on the surface of T cells. PD-1 binds to PDL-1 and PDL-2, while CTLA-4 binds to B7-1 and B7-2, with greater affinity than the costimulatory molecule CD28. The net result is reduction of T cell proliferation and decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines production.

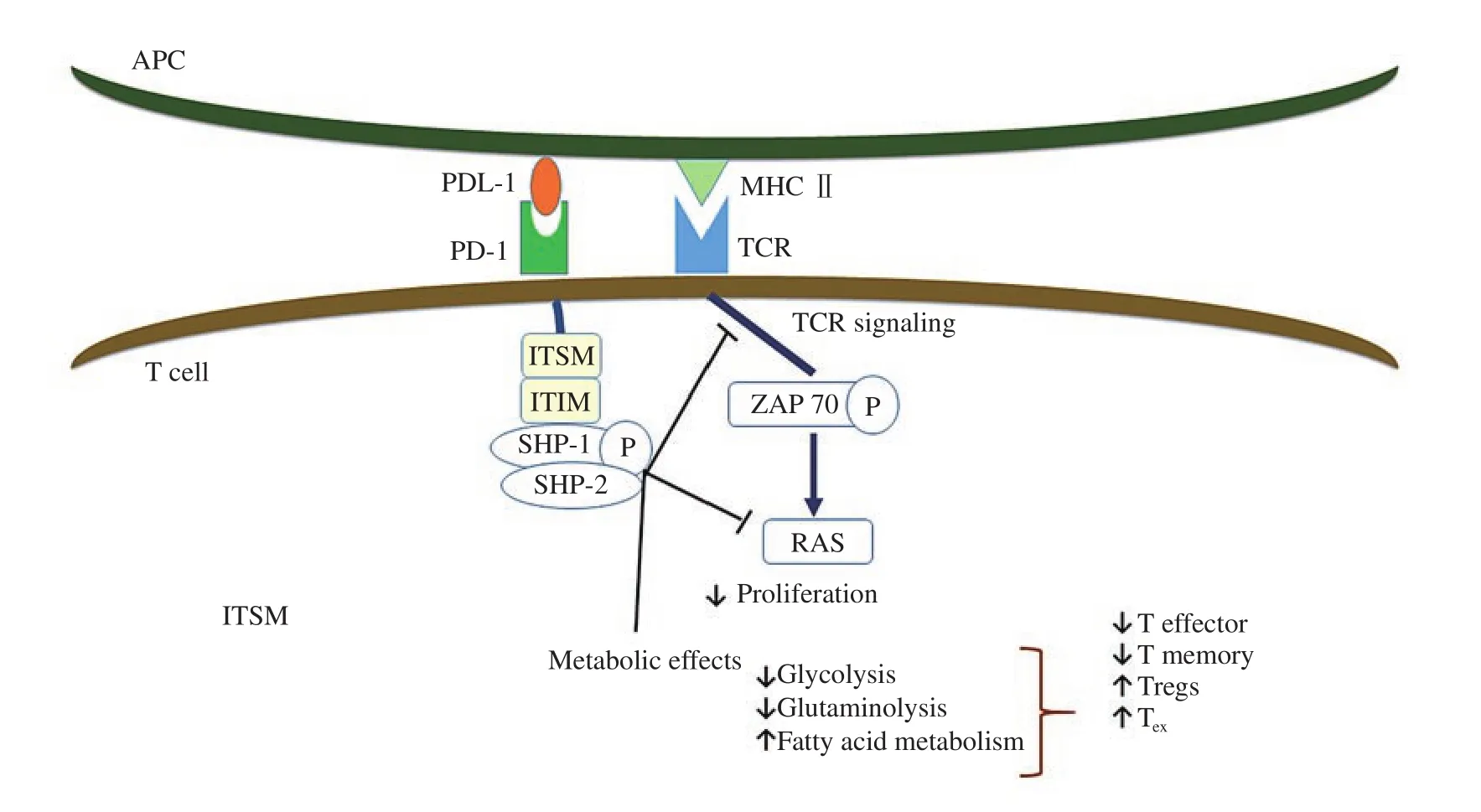

Figure 2. PD-1/PDL-1 ligation negatively regulates T cell functions. Once PD1 on T cell binds to PDL-1 on the APC, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif, which are located on the cytoplasmic end of PD-1 become phosphorylated. This results in recruitment of Src homology 2 domain phosphotyrosine phosphatase 1 and 2 (SHP-1 and SHP-2) which dephosphorylate early molecules of the TCR and CD28 signaling pathway leading to decreased clonal expansion of T cells, decreased effector and memory functions, and increased Tregs and exhausted T (TEX)phenotype.

3.5. B cell response

Regarding the humoral response, Rodrigues et al.[59] reported that hypergammaglobulinemia starts to appear in L. infantum-infected macaques during the early stages of infection and persists during the chronic phase, however, the anti-Leishmania IgG is transitory and decreases during the chronic phase suggesting that most antibodies are not Leishmania-specific. They also reported that B cells gain atypical phenotype (CD21CD27) which is responsible for the nonspecific hypergammaglobulinemia.

4. Immunosuppressive strategies used by L. donovani

Leishmania infection has been found to induce several immunosuppressive mechanisms to attenuate the effector functions of T cell and to establish the infection. Several human and animal studies have identified different immune checkpoints, such as CTLA-4, IL-27, and PD-1 on anergic T cells during chronic infection.

4.1. IL-10

Studies showed that IL-10 limits T cells functions. It was found to be co-expressed with IFN-γ by the effector T cells, which are termed as type 1 regulatory cells, which aim to protect the tissues from inflammation, however, they were found to support the infection through decreasing the effector functions of T cells[60]. VL in humans is associated with increased circulating plasma IL-10 levels. Also,IL-10 mRNA levels increased in spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes. Additionally, following parasite antigen stimulation, whole blood cells from VL patients exhibited more IL-10 production. IL-10 suppresses the dendritic cells (DCs) and renders the macrophages unresponsive to stimulation through reduction of MHC II expression,decreasing NO and TNF-α release which leads to decreased activation of Th1 cells and reduced parasite clearance[5,61,62]. IL-10 endorses T cell exhaustion[63]. Notably, mice lacking IL-10 can resist leishmaniasis[64]. In addition, Gautam et al.[65] have demonstrated that targeting IL-10 in splenic aspirate cultures obtained from VL patients could control the parasite number and increase Th1 cell cytokines.

4.2. CTLA-4

CTLA-4 on T cells is an important immune check-point as a vital controller of self-reactivity. It is up-regulated on primed T cells,particularly Tregs[66,67]. Mice lacking CTLA-4 showed a fatal overactivated phenotype resulting in intense autoimmunity. This finding confirms the salient contribution of CTLA-4 in keeping immune tolerance[68,69]. The main function of CTLA-4 is to directly control the activation of the stimulatory CD28 pathway via its ligands, B7-1(CD80) and B7-2 (CD86), where CTLA-4 binds to the shared CD28-ligands expressed by APCs[70]. Of note, CTLA-4 binding to B7-2,not B7-1, is linked to Th2 phenotype observed in both helminthic and L. major infections[71]. Blockade of CTLA-4 decreased the parasite load, increased frequencies of IFN-γ producing cells,accelerated the hepatic granulomatous response[72], and increased the drug efficacy in animal models of L. donovani[73].

4.3. IL-27

IL-27 is implicated in VL as a regulatory cytokine. Patients with active VL show increased IL-27 levels, which is important,along with IL-21, for promoting T cells to produce IL-10[74].IFN-γ enhances the production of IL-27 from macrophages which stimulates IL-10 release, decreases IL-17, and IL-22 as a feedback mechanism to decrease the tissue damage[75]. Notably, Rosas et al.[76] reported that following L. donovani infection, mice lacking IL-27 receptors showed increased Th1 response with consequent marked hepatic pathology.

4.4. Tregs

Tregs limit autoimmunity via inhibition of possibly self-reactive T cells[77]. Several studies have reported that Tregs accumulate in VL models where they produce IL-10, TGF-β, IL-35, and CTLA-4[78,79].

4.5. Dendritic cells

DCs contribute to the early T cell response against Leishmania as they help their switch to memory T cells. Intriguingly, DC-specific ICAM-3-grabbing non-integrin receptor, was reported to support the parasite survival[80]. DCs-based immunotherapy combined with antimonial compounds has been successful in animal models[81].

4.6. PD-1/PDL-1 pathway

The immune system maintains critically balanced mechanisms to eliminate pathogens and at the same time minimize self-reactivity and tissue damage. PD-1 (CD279) belongs to the CD28 family that works as a T cell inhibitory receptor. PD-1 accounts for T cell dysfunction observed in chronic infections and malignancies. It is detected on both activated and anergic T cells following TCR binding[82] .

PD-L1 (B7-H1, CD274) and PD-L2 (B7-DC, CD273) are the solely recognized ligands for PD-1. They belong to B7 family[83].PD-1/PDL-1/2 pathway is essential for regulating T cell response in different animal models of infections, malignancies, and autoimmunity. Of note, mice deficient in PD-1 have evolved autoimmune diseases such as glomerulonephritis, arthritis, and cardiomyopathy[84].

4.6.1. Regulation and expression of PD-1/PDL-1 pathway

PD-1 is a 288 amino acid expressed on thymocytes changing from double negative (CD4CD8) to double positive (CD4CD8) phase,on T and B lymphocytes post-activation, and on macrophages[85].PDL-1 and PDL-2 are differentially expressed in multiple tissues suggesting the possibility of post-transcriptional modification.Activated macrophages, DCs, T, and B lymphocytes express PDL-1,while PDL-2 is expressed on inflammatory macrophages and activated DCs[86].

PD-1 is enhanced on T cells following TCR activation. Cytokines signaling through the common gamma chain were reported to have a role in PD-1 up-regulation[87]. T-bet is a transcription factor which inhibits PD-1 expression directly. With prolonged exposure to antigen, T-bet is down-regulated, resulting in PD-1 up-regulation[88].IL-6 and IL-12 can also control PD-1 via interaction of distal regulatory molecules with PD-1 promoter[89].

Similarly, PDL-1 is regulated by B cell receptor and TCR signaling.Several gamma chain signaling cytokines, IL-4, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor have significant role in PDL-1 and PDL-2 expression on macrophages[90]. IFN-γ up-regulates PDL-1 in non-lymphoid tissues where PDL-1 promoter was found to have several IFN-γ responsive elements[91].

PDL-1 expression was detected in several kinds of human tumors[92]. Moreover, some human cancer cell lines were also found to up-regulate PDL-1 upon IFN-γ stimulation, suggesting that tumors may evade the immune response via PD-1/PDL-1 interaction[93]. Additionally, loss of phosphate and tensin homolog can lead to increased expression of PDL-1[94].

4.6.2. Signaling pathways of PD-1/PDL-1 pathway

PD-1 binding inhibits the expression of transcription factors involved in effector T cell response (Figure 2). It exerts its negative effect when cross-linked with TCR hindering glucose utilization,cytokine release, proliferation, and persistence of T cells[95] .

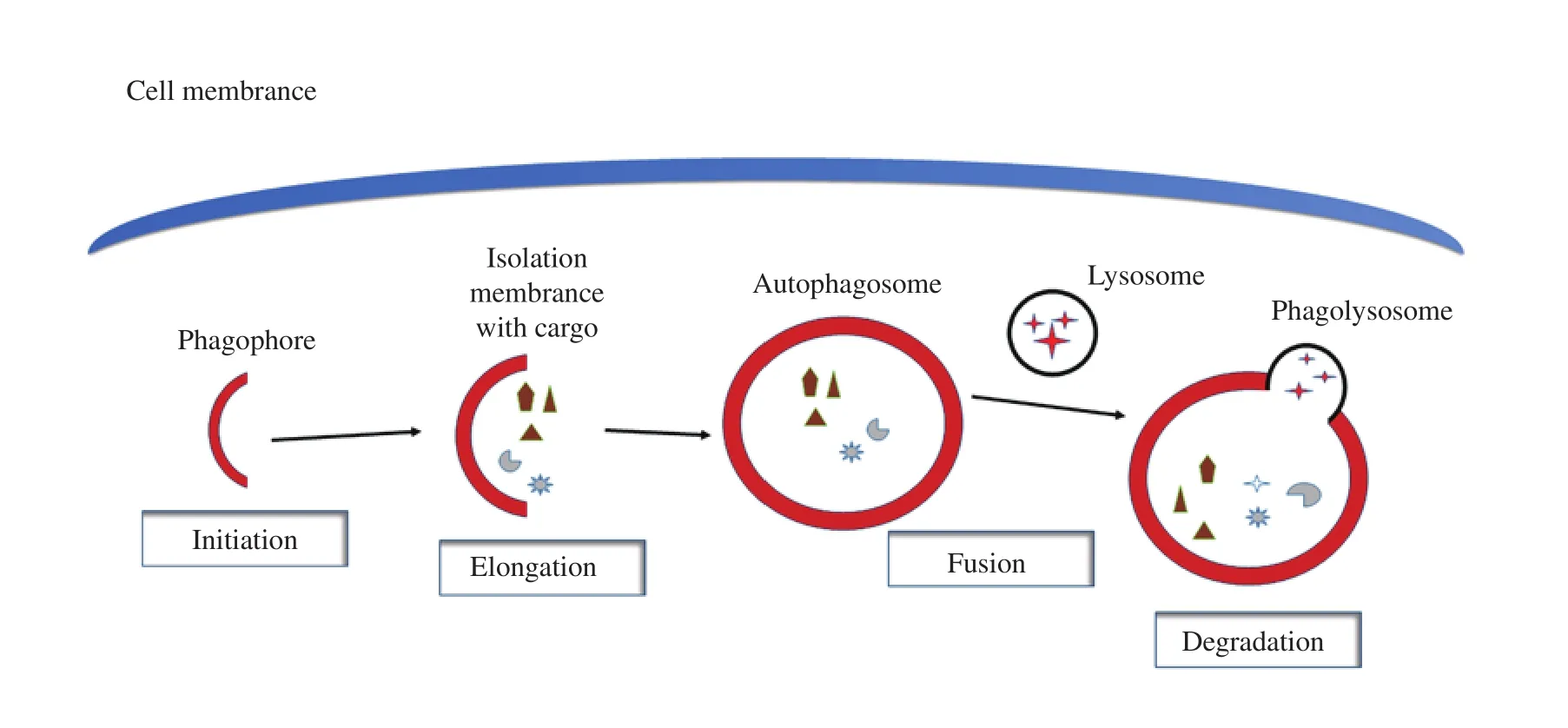

Figure 3. The autophagy steps. The autophagy process contains several steps: Initiation, elongation, fusion, and degradation. It starts with formation of the isolation membrane, the phagophore, which extends and surrounds the cargo, forming the autophagosome with the cargo inside. Autophagosome unites with the lysosome leading to formation of the phagolysosome and the lysosomal enzymes start to digest the components.

Once TCR is activated, PD-1 engages, accumulates and localizes to the TCR complex. This results in phosphorylation of the immune-receptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif and immunereceptor tyrosine-based switch motif which are present on the cytoplasmic end of PD-1, causing recruitment of SHP-1 and SHP-2 that dephosphorylate early signaling elements of TCR and CD28,specifically, the RAS/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways leading to their inhibition[96]. It also promotes TGF-β-mediated signaling with enhanced differentiation of na?ve T cells into inducible regulatory T cells[97].

Different metabolic processes are crucial to determine T cell fate.Chang et al.[98] found that glycolysis accompanies effector T cells differentiation, while fatty acid oxidation helps the conversion of the effector T cells to a memory cells or Tregs. PD-1 ligation was found to inhibit glycolysis and glutaminolysis, but increased the oxidation of fatty acids[99].

4.6.3. PD-1/PDL-1 pathway and anti-tumor immunity

PD-1 ligation dampens the anti-tumor immune response. Various studies have confirmed that different types of cancers express PDL-1 with associating poor prognoses[100,101]. Besides cancer cells,PDL-1 and PDL-2 were found to be expressed on various cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) such as macrophages, mainly M2.Interestingly, high expression of PDL-1 in the TME indicates better response to PD-1/PDL-1 blockade therapy[102].

PD-1/PDL-1 interaction in the TME down-regulates signaling pathways essential for tumor antigen recognition by T cells. It inhibits their differentiation into effector and memory phenotypes and promotes exhausted T (T) and Treg phenotypes. Moreover, it endorses persistence of cancer cells through PDL-1 mediated antiapoptotic signals[103,104]. Blockade of the pathway decreases the survival of the cancer cells and enhances anti-tumor T cell functions resulting in tumor regression[105]. For instance, Nivolumab was the first anti-PD-1 antibody showing efficacy in different types of malignancies, including melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and nonsmall cell lung cancer[106].

Anti-PDL-1 antibodies interfere with binding of PD-1 to PDL-1 but it causes less toxicity since it allows PD-1 to interact with PDL-2, which contributes to the peripheral tolerance[107]. Different anti-PDL-1 antibodies are used in clinical trials for patients with refractory malignancies. The lack of toxicity suggests the role of PDL-2 in achieving a good level of peripheral tolerance which is lacking in anti-PD-1 therapies[100].

4.6.4. PD-1/PDL-1 pathway and infectious diseases

PD-1 has a major regulatory function controlling both viral and parasitic infections. In acute viral infections, antigen specific CD8T cells get activated, expand and convert into effector cytotoxic T cells which defeat the invading pathogens efficiently, then a small number converts to memory cells and the rest of these effector cells undergo apoptosis. In contrast, during chronic viral infections,prolonged antigen exposure causes loss of effector T cell functions with inability to differentiate into memory cells and the cells become in an unresponsive and exhausted state with failure to clear the infection[82]. Tshowed increased expression of PD-1 as well as other inhibitory receptors, however, PD-1 blockade was enough to reinvigorate a considerable number of those exhausted cells.Additionally, the use of anti-PD-1 in patients with human immune deficiency virus[108] and hepatitis C virus[109] caused significant increase in the antigen-specific T cells and decreased the viral burden. Simultaneous blocking of PD-1 and the inhibitory receptor lymphocyte-activation gene (LAG)-3 reinvigorated the exhausted cells and cleared the virus in mice infected with chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus[110].

Regarding parasitic infections, PD-1 blockade was used in several studies. In toxoplasmosis, it restored exhausted CD8T cell functions, and resulted in decreased reactivation of the parasite and enhanced survival of chronically infected mice[111]. In malaria infection, in vivo blockade of PDL-1 and LAG-3 improved CD4T cell response, enhanced anti-malaria antibodies, and rapidly eliminated malaria stages from the blood[112].

4.6.5. PD-1/PDL-1 role in Leishmania infection

PD-1/PDL-1 interaction was reported to enhance the apoptosis of T cells, increase the anti-inflammatory cytokines by leukocytes from peripheral blood and spleen, and increase the magnitude of infection in L. infantum-infected dogs[58]. In a similar animal model, Esch et al.[10] confirmed that ex vivo blockade of PDL-1 promoted return of CD4T cells functions, CD8T cells proliferation, but not IFN-γ production, dramatically increased ROS production in co-cultured monocyte-derived phagocytes, and led to decreased parasite load.

Joshi et al.[9] used transgenic L. donovani parasites to track Leishmania-specific CD8T cell response. The cells expressed limited expansion, functional exhaustion and apoptosis. They blocked PD-1 in vivo and were able to increase the life span of CD8T cells, however, the cytokine levels were not recovered. On the other hand, we have shown that in vivo blockade of PDL-1 in L.donovani-infected mice could rescue CD4and CD8T cells and promoted their cytokine profile, enhanced macrophages functions and antigen presentation capabilities, and increased the effector memory CD4and CD8T cells. Altogether, the parasitic load decreased dramatically[11].

Besides, Filippis et al.[113] elucidated that anti PD-1 enhances T cell expansion and pro-inflammatory cytokine release during the coculture of L. major infected human cells with PD-1lymphocytes.Another study conducted by da Fonseca-Martins et al. targeted PD-1 and PDL-1 in a mouse model of non-healing L. amazonensis infection. They found that anti PD-1 and anti PDL-1 promoted IFN-γ expression by CD4and CD8T cells, respectively. It caused significant decrease in IL-4 and TGF-β with consequent decrease in the parasitic burden. Noteworthy, neither anti-Leishmania antibodies nor IL-10 levels were affected[114].

5. Autophagy

Autophagy is the process which deals with degradation of unwanted cellular components through the lysosomes. There are 3 main kinds of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperonemediated autophagy.

Macroautophagy includes the sequestration of the cellular components into the double membrane autophagosome, which unites with the lysosomes where the components get digested and the cell can use them again for its function. It is dependent on the autophagy related proteins (ATGs)[115]. Microautophagy is a ATGs-independent process which involves the small proteins of the cytoplasm and is characterized by invaginations of the lysosomal membrane into the lysosomal lumen. Chaperone-mediated autophagy depends on direct transfer across the lysosomal membrane[116].

There are other forms of autophagy which involve particular components such as lipophagy where the lipids are targeted;mitophagy where damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria are targeted; aggrephagy where the protein aggregates are targeted; and xenophagy where intracellular microorganisms are degraded by the macroautophagic pathway[117].

5.1. The autophagy pathway

Starvation stimulates the autophagy process. It deactivates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), with resulting autophagy stimulation. As illustrated in Figure 3, the autophagy process contains several steps: initiation, elongation, fusion, and degradation[118]. It starts with assembly of some ATGs to form the elongation membrane known as the phagophore, which appears as a double layered crescent in the cytoplasm. Several ATGs are involved in the initiation step such as Beclin 1 and ULK1. During the elongation step, the phagophore elongates and surrounds the cargo to form a closed double layered autophagosome with the cargo inside.In this step, the micro tubule associated protein light chain 3 (LC3)Ⅰ is lipidated to form LC3 Ⅱ. Then the autophagosome unites with the lysosome, forming the phagolysosome and the lysosomal enzymes start to digest the components[119].

5.2. Autophagy functions in infections and immunity

Autophagy is responsible for maintaining the cellular integrity through clearing the cellular debris and regenerating the metabolic precursors, thus achieving cellular and tissue homeostasis and suppressing oncogenesis. It also recycles damaged organelles[120].Moreover, it regulates lipid metabolism, and prevents the accumulation of poly-ubiquinated protein aggregates which accumulate during aging, stress and diseases, and affect the protein structure and folding[121].

From an immunological perspective, autophagy plays a dual role.It may favor an inflammatory or immune-regulatory response,according to the antigens presented, thus, switch of T cells towards the inflammatory Th1 or the anti-inflammatory Th2 may be affected. The balance between both types is crucial for leishmaniasis outcome[122].

Autophagy has important role in infections as it affects the immune response through degradation of the invading organisms within the autophagic compartments (xenophagy), like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Herpes simplex virus type 1, and Toxoplasma gondii[117].It also suppresses the inflammatory response by down-regulating the protective cytokines and inhibiting the inflammasome-dependent maturation and secretion of the inflammatory cytokines[123].Additionally, autophagy can affect the adaptive immune response via affecting the antigen presentation and the lymphocyte development[124].

5.3. Autophagy and Leishmania

Leishmania invades the macrophages and escapes the microbicidal mechanisms of the macrophages by inhibiting the formation of the phagolysosomes. L. major surface metalloprotease GP63 was reported to prevent the formation of mTOR complex 1 (mTORc1)and inhibits the recruitment of LC3 to the phagosomes[125]. Of note, the LC3-associated phagocytosis plays a crucial role in the phagocytosis of dead cells and organisms such as Leishmania,promotes tolerogenic pathways by induction of TGF-β and IL-10 and dampening IL-1β and IL-6[126].

A study conducted by Crauwels et al.[16] has shown that L. major inoculum contains apoptotic-like Leishmania which are up-taken by LC3-associated phagocytosis and triggers autophagy activation,induces TGF-β and IL-10, and dampens IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α production. In the same study, autophagy inhibition by means of Spautin-1 increased T cells proliferation, however, the parasite load was not affected significantly.

Autophagy was found to increase the replication of L. amazonensis inside macrophages and its inhibition using 3 methyl adenine decreased the parasite index in infected mice[127]. Autophagy stimulation may enhance the parasite survival through increased presentation of self-antigens[128], provoking immune-silencing mechanisms with dampened adaptive immunity, decreased T cell proliferation, and provision of the parasite with the nutritive support[16]. Interestingly, it was found that L. donovani uses another pathway other than mTOR to activate the host autophgy, which is inositol monophosphatase, meanwhile, Leishmania disables mTOR pathway to achieve perfect control on the autophagy process thus optimizing its persistance[129].

Autophagy was found to play opposite roles during leishmaniasis.Although host autophagy can be subverted by Leishmania to provide nutrient support, it can significantly restrict the intracellular growth of amastigotes[130]. Frank et al.[18] proved that bone marrow-derived macrophages could destroy L. major by the aid of autophagosomes,vacuoles, and myelin-like structures. The autophagic clearance of L. major was attributed to cathepsin E and BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3, however, the expression of these 2 proteins was inhibited early during the differentiation into amastigotes. In this study, the authors described that amastigotes not surrounded by autophagosomes are rather penetrated by myelinlike structures which wrap the parasite components. The parasite cell membrane separates the digestion process from the cytoplasm of the infected cell, thus preventing antigen presentation. Of note,autophagy induction in the previous model was mTOR independent.On the other hand, activation of mTOR was observed post infection.Knocking-down of p-mTOR resulted in decreased infection burden,which is consistent with another study[131], supporting the idea that early inhibition of autophagy may protect Leishmania to secure a complete differentiation.

Contrary to the mechanisms of Leishmania entry into the macrophages, L. amazonensis was recently reported to actively invade mouse embryonic firboblasts (MEFs) via endocytosis and then gain the lysosmal markers, lysosme-associated membrane protein(LAMP1 and LAMP2)[132]. An interesting study was conducted by Halder et al.[19], who were able to find the co-localization of LAMP1 within 50%-70% of Leishmania containing vacuoles (LCVs), and LAMP2 within 35%-55% of LCVs using fluorescence microscopy,after infection of wild type MEFs and human epithelial cell line A549 with L. donovani at different time points. Intriguingly, they found that LAMP-decorated LCVs were non-permissive to parasite survival and replication owing to the observation of only a few amastigotes in such vacuoles, in contrast to other vacuoles that are devoid of LAMP, which showed multiple amastigotes inside. Further,they defined a new cellular self-directed immune pathway which renders non-phagocytic cells hostile for intracellular Leishmania via IFN-γ-inducible guanylate binding proteins.

Noteworthy, guanylate binding proteins were reported to boost the autophagy machinery contributing to the antimicrobial function of LCVs[133]. Halder et al.[19] confirmed that these proteins enhance the delivery of amastigotes to the autolysosmes as they noticed reduction in LC3 staining of LCVs in GBP1A549 cells and Gbpchr3MEFs. In this study, MEFs lacking ATG3 contained higher numbers of amastigotes, concluding that, unlike phagocytes, guanylate binding proteins-mediated autophagy plays principal role in defense against Leishmania in fibroblasts.

mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and GSK-2126458) were tested in mice after intra-footpad inoculation of L. major and were found to decrease the local inflammation and the parasite load in the draining lymph nodes. Additionally, splenocytes derived from the treated animals exhibited less IL-4 expression, accordingly IFN-γ/IL-4 ratio increased, signifying Th1 biased response[134].

5.4. Interplay between autophagy and PD-1/PDL-1 pathway

Although numerous studies have pointed out the relationship between PD-1/PDL-1 pathway and autophagy in tumors, few studies have emphasized this relationship in infection. We have previously shown that anti PDL-1 immunotherapy works via dampening autophagy in a mouse model of VL[11]. In addition, Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected PD-1macrophages exhibited decreased LC3B expression in macrophages[135].

Understanding the interplay between autophagy and PD-1/PDL-1 pathway in cancer may be helpful in the context of chronic parasitic infections. Jiang et al.[136] reported that immunologic tolerance proteins such as CTLA-4, PD-1, and indoleamine 2, 3 dioxygenase,can use the autophagy process to regulate immune tolerance to tumors. Sigma 1 inhibitor promoted autophagic degradation of PDL-1 when tumor cells were co-cultured with T cells[137].

A negative correlation between autophagy and PD-1/PDL-1 pathway was reported in some studies. Autophagy deactivation was found to promote PDL-1 expression in stomach cancer[138],and vice versa, ligation of PD-1 on T cells to PDL-1 on tumor cells suppresses autophagy by triggering mTORC1 and limiting mTORC2 signaling[136]. Reduction of PD-1 by treatment increases autophagy[7]. In contrast, a positive correlation was reported in other studies. Binding of PD-1 on T cells was observed to decrease glucose uptake, resulting in enhanced autophagy through mTORC1 and AMP-activated protein kinase signaling[139]. Wen et al.[140]reported that the levels of LC3Bextracellular vesicles correlate with upregulation of PDL-1 on matched monocytes from cancer patients. Additionally, they demonstrated that tumor cell-released autophagosomes induce M2 polarization which promotes tumor growth mainly through PD-1/PDL-1 signaling.

Therefore, more researches are essential to understand the interplay between autophagy and PD-1/PDL-1 pathway in leishmaniasis, to determine which pathway is downstream of the other and to define more effective therapeutic targets for this devastating disease.

6. Conclusions

The ability of Leishmania to subvert the host immune mechanisms and to exploit it for its own survival helps the establishment of chronic infection. The induction of immunosuppressive mechanisms,especially the activation of PD-1/PDL-1 signaling in addition to the autophagy induction should be considered as targets for the future anti-leishmanial therapies. The relation between anti PDL-1 mechanism of action and autophagy inhibition should undergo further investigations to justify the use of chemical autophagy modulators to treat Leishmania. This will cut the cost of the expensive immunotherapy and will help better control of the disease in the developing countries.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

SH: research idea, collected and analyzed the data, theoretical formatting. MA: final revision of the manuscript. KE: theoretical formatting and final revision. AH: supervision of the project.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2021年5期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2021年5期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Peltzman effect and resurgence of COVID-19 in India

- Circulatory and hepatic failure at admission predicts mortality of severe scrub typhus patients: A prospective cohort study

- Morphological study and molecular epidemiology of Anisakis larvae in mackerel fish

- Circulation of Brucellaceae, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. in borderline of Iran,Azerbaijan, and Armenia

- Extensively drug-resistant Salmonella typhi causing rib osteomyelitis: A case report

- S gene drop-out predicts super spreader H69del/V70del mutated SARS-CoV-2 virus