Children of the Corn

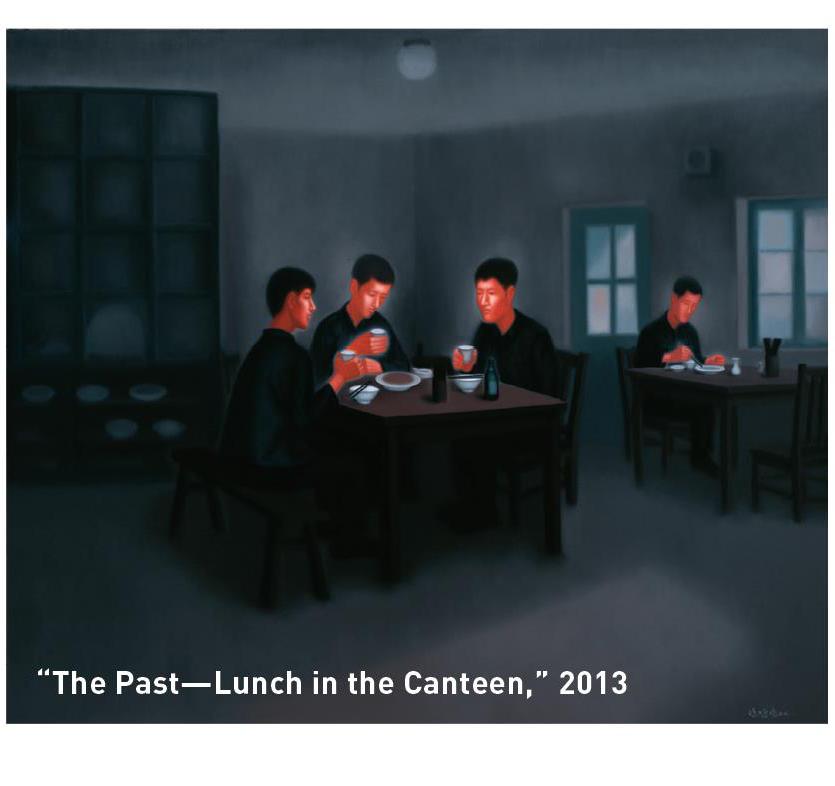

From his unbearably cute “Fatties” to his somber and malnourished portrayal of street life in his series “The Past,” the works of Pan Dehai (潘德海) arouses a mixed bag of emotions—fuzzy euphoria, but also intense unease, not least due to his juxtaposition of plump and lean, dark and garishly bright.

In the 1980s, Pan co-founded the Southwest Art Research Group, an avant-garde movement summarized by influential contemporary art critic Gao Minglu as looking “backward and inward, through images of distorted bodies or of people living a simple life.” Having fallen in love with the rustic towns and landscapes of southwest Chinas Yunnan province, Pan focused on creating contemporary art that spoke to the countrys inner psyche, and stumbled across his now-signature “corn motif”—giving the texture of corn grains to the people, plants, and landscapes he drew.

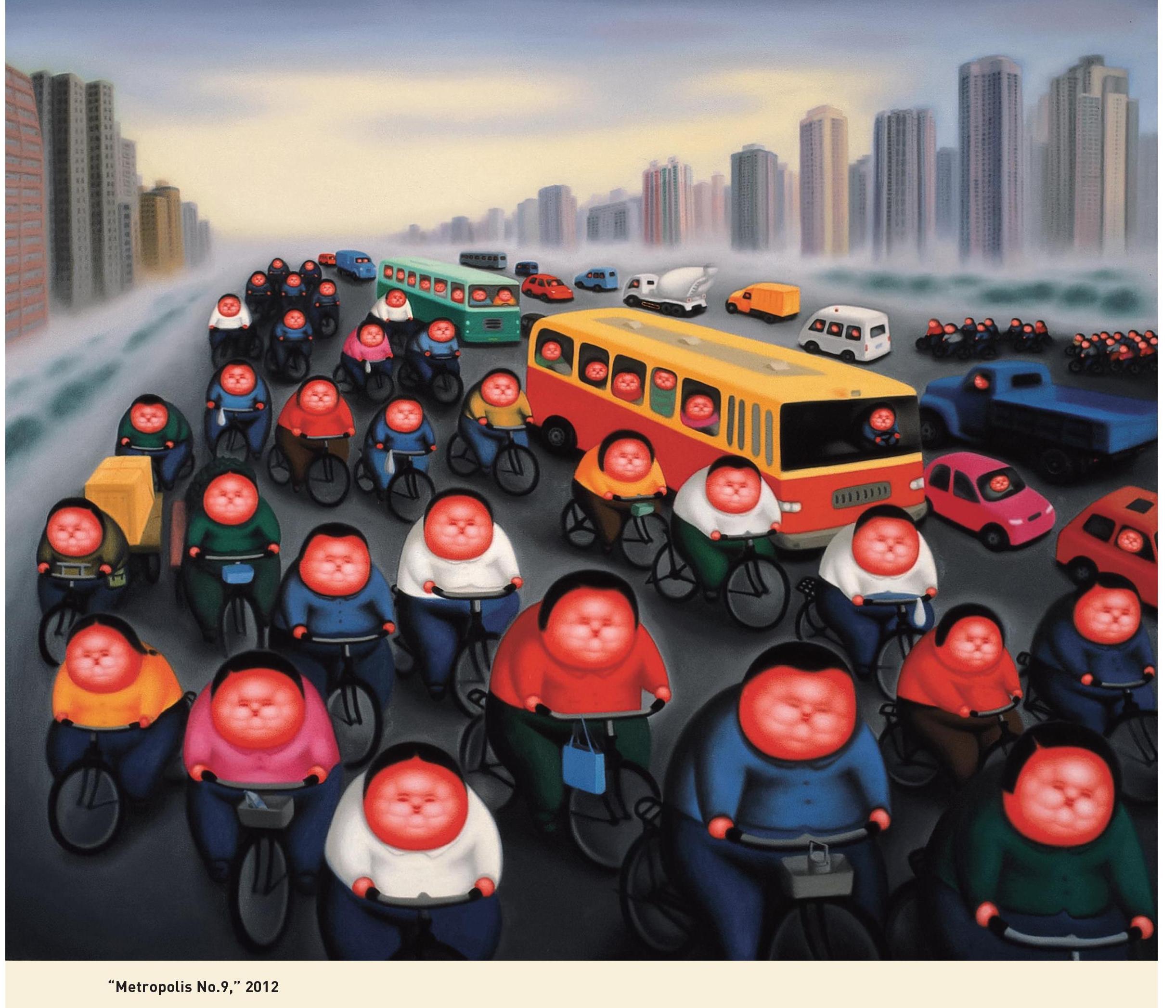

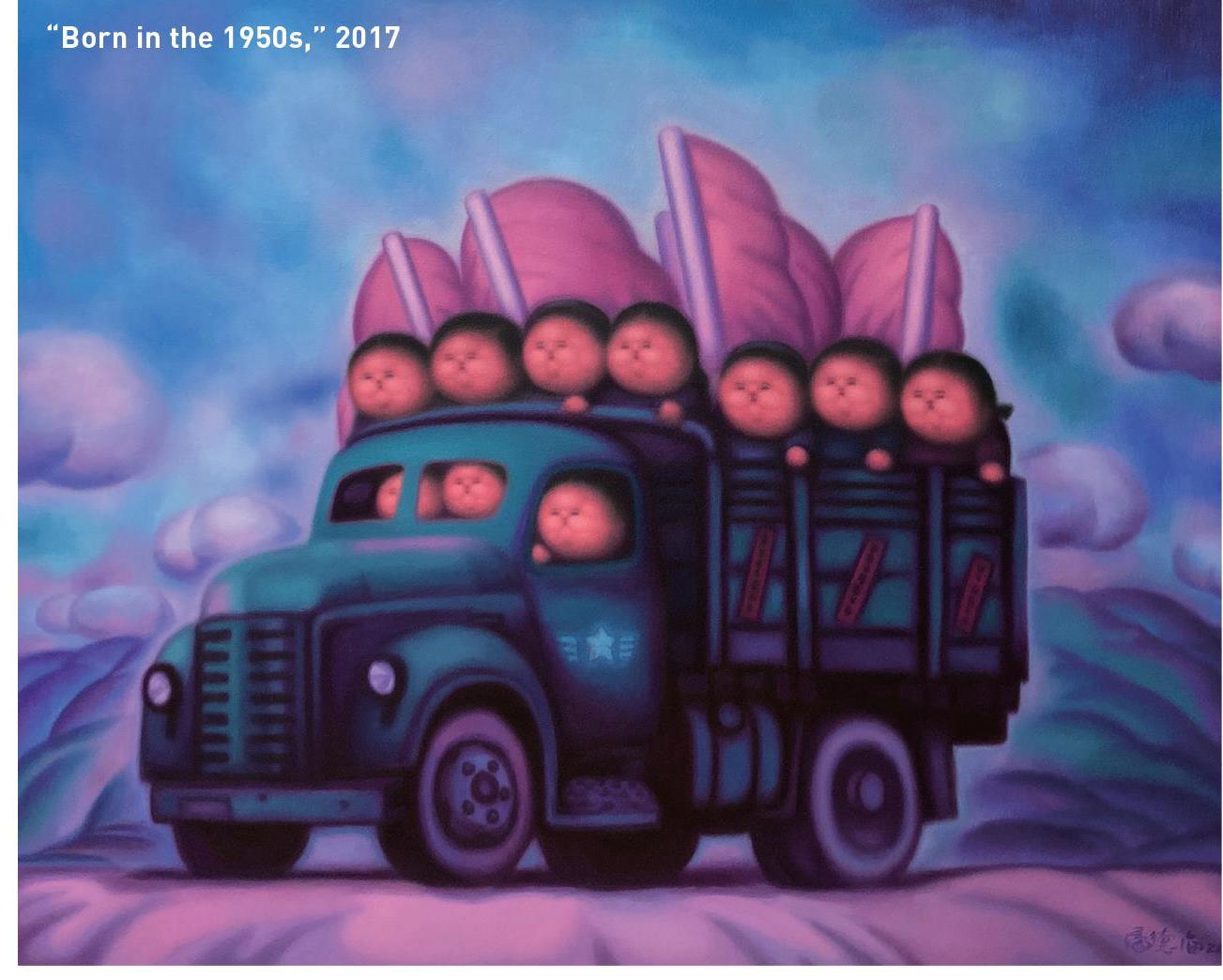

By the end of the 1990s, the “Corn People” had swollen into the “Fatties.” In Pans brush scenes from daily life, as well as images from both real and legendary historical events, emerged tubby characters with stumpy arms resting on well-rounded paunches. On several occasions, Pan has given the chubby treatment to Dong Xiwens “Founding Ceremony of the Nation” painting, as well as scenes from the Cultural Revolution, the Long March, and military parades on Beijings Changan Avenue.

There is something sinister beneath the surface of these roly-poly lumps. When viewed up close, their eyes bulge out of expressionless faces, as if the subject has been lobotomized. Were they normally proportioned, their portrayals in Pans art—fighting to get on a bus, or swarming up crowded streets—would appear depressing, even apocalyptic. In previous interviews, Pan has described the “Fatties” as an ironic commentary on the modern world: its worship of consumerism, its neglect of both ideology and individualism. It feels like the grinding smog-bound industrial towns of L. S. Lowry have been given the Botero treatment, puffed up to comic proportions as an absurd commentary on Chinese visions of plenty.

Below is TWOCs interview with Pan, edited for brevity and clarity:

What made you choose to study oil painting?

I entered university in 1978, at the beginning of the reform period. A large number of Western modernist art books were introduced into China, as well as books on modern literature, philosophy, psychology, and humanities from the West. Undoubtedly all of this was a great shock, and I felt like I was so hungry that I ate indiscriminately. Everything was new to me. I spent my days painting and my evenings in the reading room, reading Western philosophy, and I was excited by all of it. At first, I admired European classicism, then I became addicted to late impressionism, and then modernism and its various genres. I tried new forms of art between completing class assignments, but the only one that moved me was Western oil painting.

You have said that you stumbled across your corn motif through “scrubbing unsatisfactory colors.” Can you elaborate on this?

In the mid-to-late 80s, the world was still in chaos, and art was no exception. Trivial and meaningless daily routines still plagued me. I was tired of repeating myself, wandering, thinking about the way forward for art; and I looking for a way out of my confused and bewildered state. One night, I finished a small painting and was not satisfied, so I dejectedly put my brush to the canvas and made some random strokes to clean off the colors. When I looked at it from a distance, I was surprised. The colors left behind created a new image. From that moment, I discovered new possibilities in painting, and I started to create watercolors.

The corn motif was a process of evolution. I initially painted fuzzy clumps that had no borders, and they gradually changed to resemble grains of different sizes. Then they transformed into [pictures of] undulating brick walls, and finally of the sky and earth. The landscape and plants are all formed out of grains, which are the basic unit of composition. In this process, they came to resemble corn.

Whats the meaning of fat people in your work?

The fat people have a side thats surreal, absurd, humorous, and satirical. They also have a side thats tiny and cute. They represent materialism, greediness, dissatisfaction, and a criticism of reality. Each of my works [featuring the “Fatties”] have different content, so they symbolize different things within each work. Their meanings are transformed by each work and vice versa.

What was the inspiration behind the “Past” series?

I wanted to create a series of paintings from a personal perspective, composed from scenes, stories, and memories, combining details from history and my complicated feelings about it. Every scene is independent yet connected to the rest. After “The Past,” I painted the “Childhood” and “Folk Theater” series. They all capture a special and fast-disappearing era. These memories are always tormenting me, so I am always rethinking them.

In your “Fatties” series, there are some reproductions of famous political images. How are they received in China?

Compared with previous decades, todays audiences have made great progress in their appreciation of the arts. Some of my works have involved politics, but they were all presented in a humorous, cute, and clumsy way. Lots of people smile while watching them, saying “Its interesting” or “Its so funny.” Of course, some people are surprised that you can portray the leaders in this way, but they can accept it. Theres no problem with that.

In the course of your career, your expressions of China have changed from splendid and prosperous to gloomy and constructive. Why?

Fundamentally, I have doubts about things that change very fast. This is what is happening in China today, and I miss the old China. In the 60s and 70s, we lacked material goods, but our lives were relaxed and free. There was no stress, pollution, or trash. The air was fresh and there were green mountains and clear rivers everywhere. You could see the fish in the waters.

China now is too commodified. Peoples needs are very simple. Why are people unhappy nowadays? Its because we have too much and are overburdened. Are we living a better life now by indefinitely advancing the cost of living? We are too busy for leisure—is that what we want?

The only time I touched on this subject matter was many years ago in the “Metropolis” series, which was based on my experience of cities up until then. But when I later came to Beijing, it completely exceeded my imagination: the rush of people, the rush of cars. Everything was a human scene encapsulated by the word “rush.” The whole city is in a hurry, forgetting yesterday, losing the memory of today, and not knowing whether there is a tomorrow. You need to survive now! Who cares about the future? You cant stop even if you want to. From a macroscopic point of view, people are like ants, busy all the time, rushing around to finish their lives in a hurry.

– Alex Colville

Pan Dehai was born in 1956 in Siping, a city in northeastern Chinas Jilin province. He graduated with a degree in fine art from Northeast University in 1982. The same year, he moved to Yunnan province, where he co-founded the Southwest Art Research Group in 1986 with Zhang Xiaogang and Ye Yongqing. Exhibiting in Shanghai and Nanjing, the group is considered a key institution within Chinas New Wave art movement of the mid-80s. In 1992, Pan moved to Beijing, where he worked for eight years as a freelance artist. Since 2002, he has been a lecturer at Yunnan Arts University in Kunming. His previous featured exhibitions include the China/Avant Garde exhibition (Beijing, 1989), Hong Kong Arts Center (1993), and the Venice Biennale (2011).

“Metropolis No.9,” 2012

“Born in the 1950s,” 2017

“The Past—Lunch in the Canteen,” 2013

“Metropolis No.3,” 2009

“Childhood—Childrens Book Shop,” 2017

“Pimples No.6,” 1996

Images provided by Pan Dehai, Courtesy of Yang Gallery

漢語(yǔ)世界(The World of Chinese)2021年5期

漢語(yǔ)世界(The World of Chinese)2021年5期

- 漢語(yǔ)世界(The World of Chinese)的其它文章

- China’s Other Vaccine Drive

- 三味書(shū)屋

- The Changing Face of YinggeDance

- Upstaged

- SilentEpidemic

- 學(xué)中文