Focal nodular hyperplasia associated with a giant hepatocellular adenoma: A case report and review of literature

Sérgio Gaspar-Figueiredo, Amaniel Kefleyesus, Christine Sempoux, Emilie Uldry, Nermin Halkic

Sérgio Gaspar-Figueiredo, Amaniel Kefleyesus, Emilie Uldry, Nermin Halkic, Department of Visceral Surgery, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne 1011, Switzerland

Christine Sempoux, Department of Pathology, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne 1011, Switzerland

Abstract BACKGROUND Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) are wellknown benign liver lesions.Surgical treatment is usually chosen for symptomatic patients, lesions more than 5 cm, and uncertainty of diagnosis.CASE SUMMARY We described the case of a large liver composite tumor in an asymptomatic 34-year-old female under oral contraceptive for 17-years.The imaging work-out described two components in this liver tumor; measuring 6 cm × 6 cm and 14 cm × 12 cm × 6 cm.The multidisciplinary team suggested surgery for this young woman with an unclear HCA diagnosis.She underwent a laparoscopic left liver lobectomy, with an uneventful postoperative course.Final pathological examination confirmed FNH associated with a large HCA.This manuscript aimed to make a literature review of the current management in this particular situation of large simultaneous benign liver tumors.CONCLUSION The simultaneous presence of benign composite liver tumors is rare.This case highlights the management in a multidisciplinary team setting.

Key Words: Liver; Focal nodular hyperplasia; Hepatocellular adenoma; Composite tumor; Video vignette; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) has become a pretty well-known disease in the past two decades.It is defined by a benign hyperplasic nodule with a central scar, appearing in the normal liver parenchyma, and is composed of normal hepatocytes in a multinodular structure[1].Its incidence is between 0.6%-3%, predominantly affecting females patients (80%-90%) in their third or fourth decade.The pathophysiology is thought to be due to an increased arterial flow that leads to secondary hepatocellular hyperplasia[2,3].The correlation with oral contraceptives (OCs) is unproven but very likely, given that OCs are taken almost exclusively by women (sex ratio 9:1) and the proven correlation between OCs and change in lesion size[4,5].

Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is a benign lesion with a malignant potential between 4% and 8%, according to recent works of Fargeset al[6] and Sempouxet al[7].It classically arises in a noncirrhotic liver, in young females with an OC background.However, the understanding of HCA has evolved dramatically and we now know that it can also develop in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, certain vascular malformations, or alcoholic cirrhosis.Moreover, there are a wide variety of subtypes of this complex disease, making it very difficult to establish treatment guidelines[8-10].

In this present article, we aimed to describe the detailed management of a rare simultaneous case of FNH and HCA and a brief review of the literature.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 34-year-old woman in general good health, with a medical history of oral contraceptives (desogestrel, ethinylestradiol) for 17 years consulted her general practitioner (GP) for a check-up.

History of present illness

She was completely asymptomatic.

History of past illness

She had no past illness.

Personal and family history

The patient had no past medical history except a knee orthopedic surgery 1 year before, had a stable weight with normal body mass index (21.1 kg/m2) and no familial medical history.

Physical examination

During the examination, her GP found a mobile and palpable abdominal mass of more than 10 cm in diameter, with no skin bulging at the Valsalva's maneuver (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Pre-operative patient’s supine and stand-up picture - no external signs of tumor.

Laboratory examinations

The blood exams were normal, except for an elevation in alkaline phosphate level of 519 U/L (normal range = 36-108).Tumoral markers were normal.

Imaging examinations

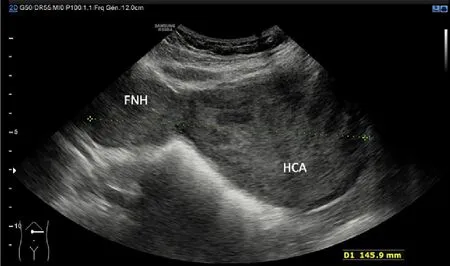

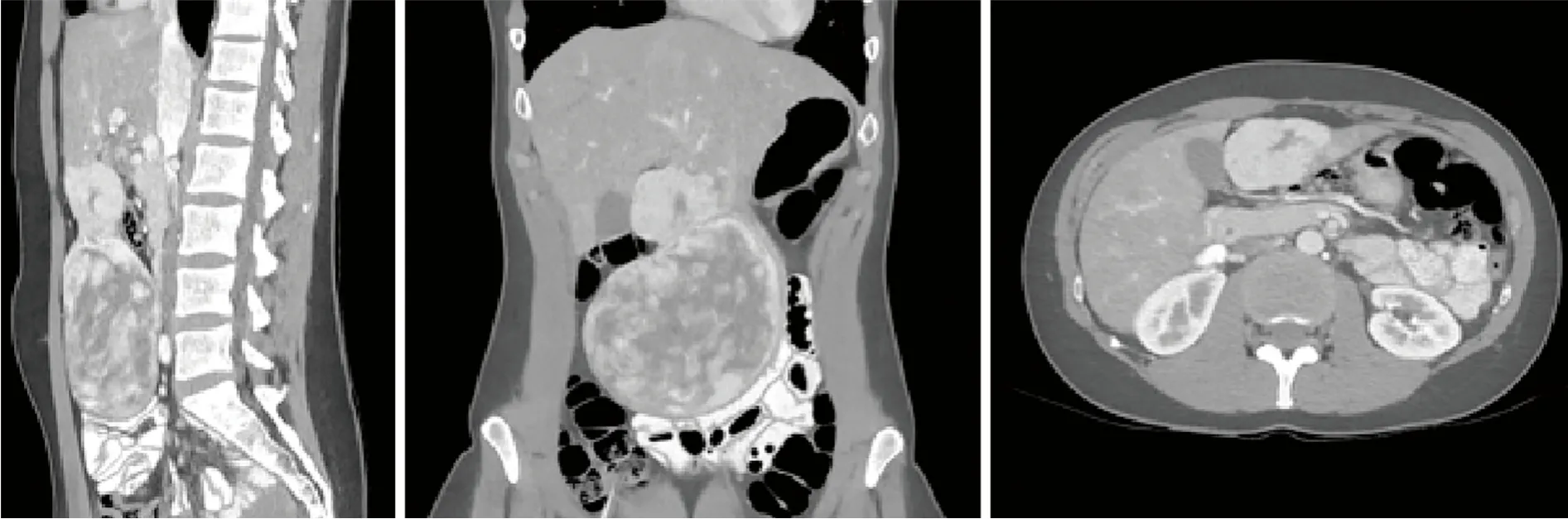

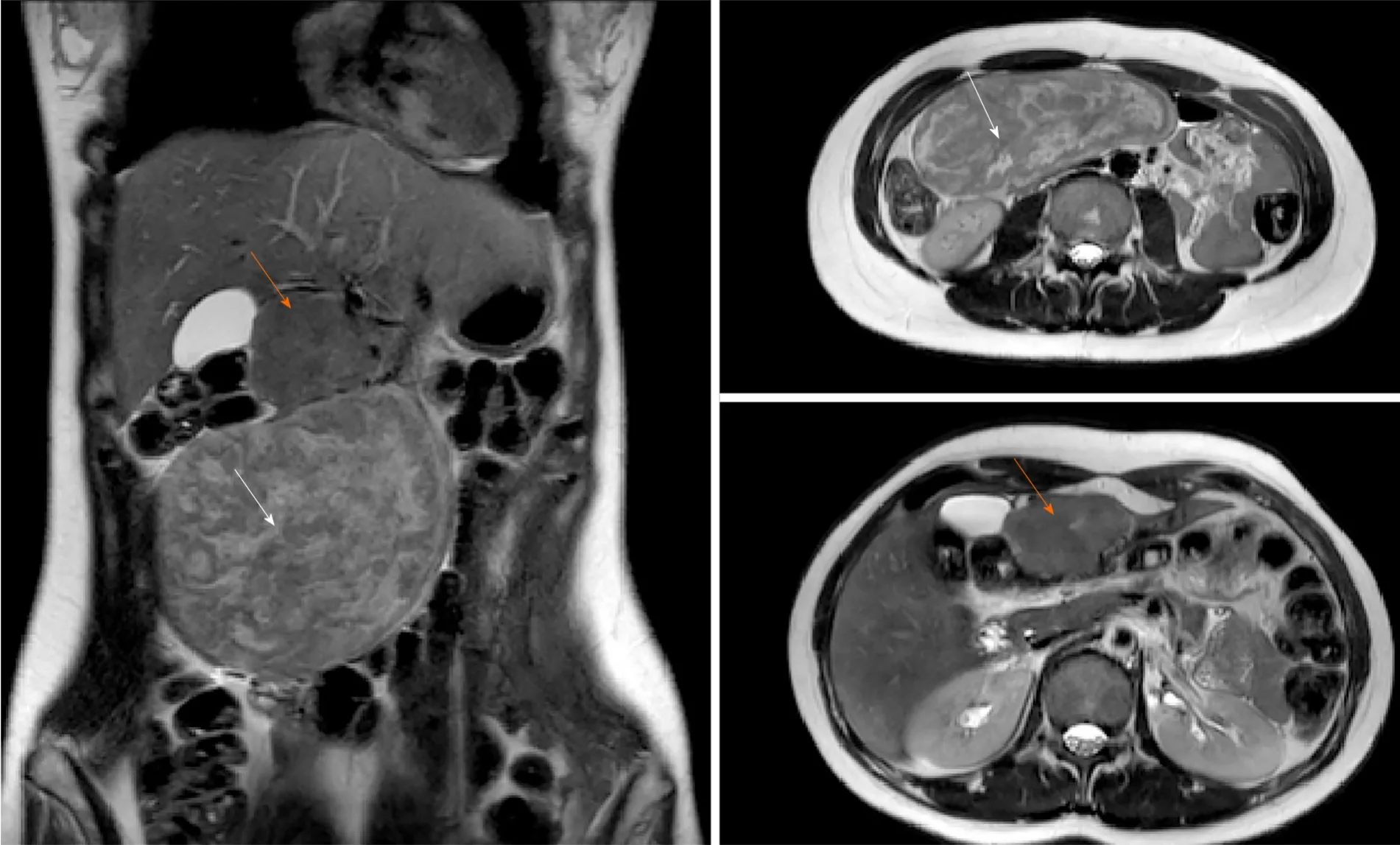

Abdominal ultrasound revealed an aspecific giant mass next to the left hepatic lobe.A computed tomography (CT scan) revealed a double mass attached to the left lobe of the liver.The first one had the typical characteristics of FNH and the second one of uncertain dignity.Further magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a 6 cm x 6 cm mass suggestive of FNH in the inferior part of segment III.This 6 cm lesion was right next to a second one measuring 14 cm × 12 cm × 6 cm which dignity was unclear.The differential diagnosis was between an HCA, a hepatocellular carcinoma (fibrolamellar variant), or an atypical FNH (Figures 2-5).

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

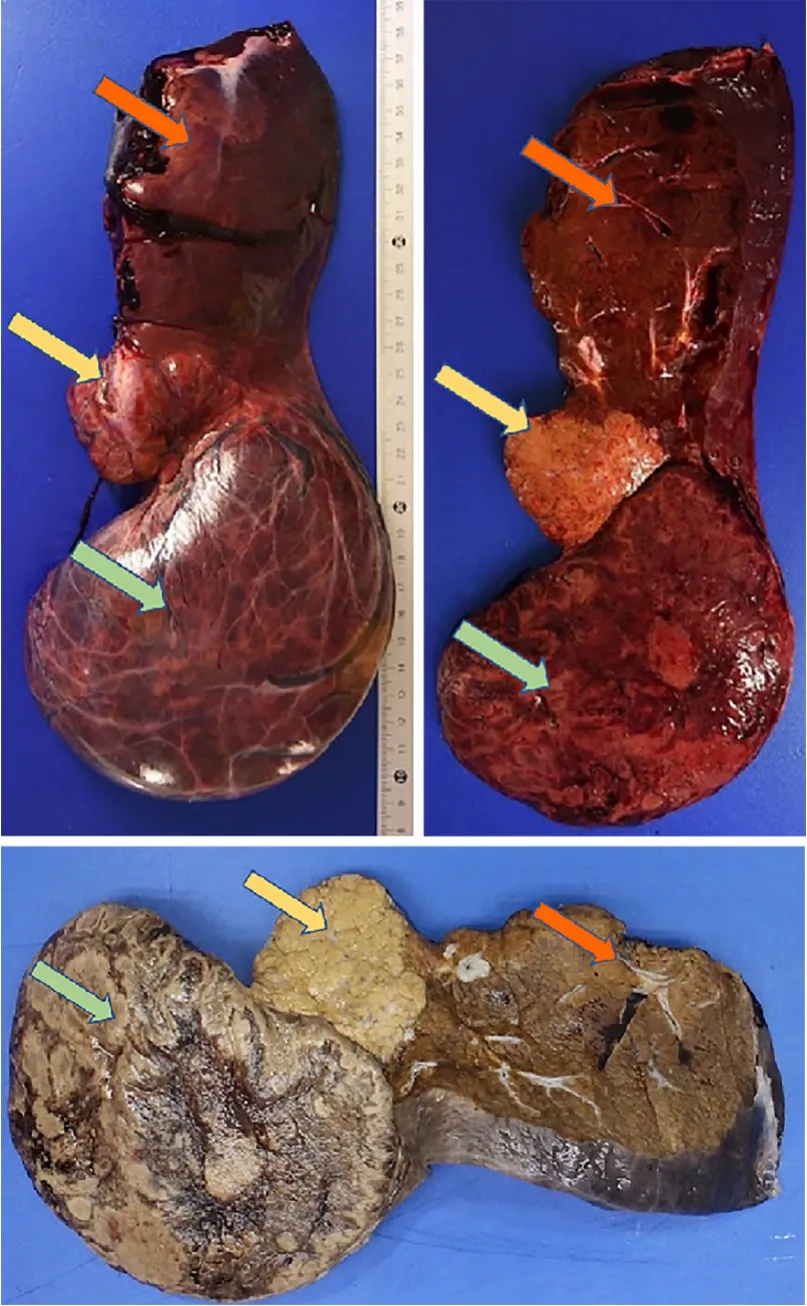

The pathologist’s report confirmed the diagnosis of 6 cm FNH resected with good margin and showed a non-beta-catenin-mutated HCA (inflammatory subtype with more risk of malignant transformation) (Figure 6).

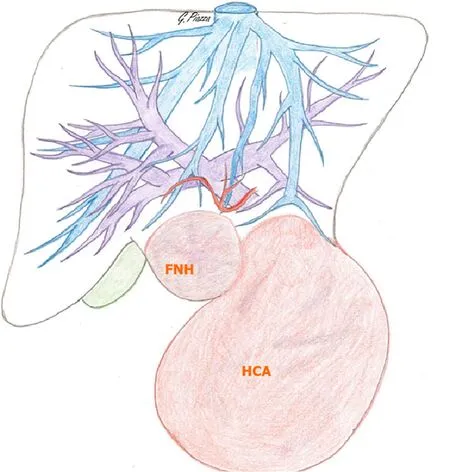

Figure 2 Preoperative drawing - tumor and liver major vessels’ relationship (credits: Dr.Giulia Piazza).

Figure 3 Ultrasonography with a sagittal view of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma.

Figure 4 Computed tomography late portal phase, with a multiplanar reconstruction of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma.

Figure 5 Magnetic resonance imaging - T2 sequence.

Figure 6 Anatomopathological pictures (top: fresh sample; bottom: formalin-fixed sample), sagittal section plane.

TREATMENT

Indication for surgery was retained during a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting as the first option for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

The surgery was completed without complication.We summarize hereafter the key points of the minimally invasive procedure.After inserting 4 trocars for the laparoscopy (para-umbilical, right and left flank, subxiphoid) and staying away from the large dual mass which limited the range movements, we performed an ultrasound confirming a pedunculated mass (FNH) highly vascularized attached to segment III and a second component pedunculated between segment II and III.The mass showed no adhesion with the segment IV and the gallbladder allowing a left lobectomy.Dissection was performed with ultrasonic shears (Ultracision Harmonic, Ethicon Inc., NJ, United States) and transsection was completed with a 60mm stapler (tri-staple vascular cartridge, Endo-GIA, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States).We extracted the specimen with both lesions through a suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incision.The operative time was 122 min.Blood loss was minimal (50 mL) (Video 1).

The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 3.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The MDT meeting proposed a 1-year MRI follow-up with oral contraceptive discontinuation.

One month after surgery, the patient was good without any complaint, her scar evolution was satisfactory and there was no sign of an early incisional hernia.

DlSCUSSlON

The interest of this case lies in the simultaneous discovery of 2 adjacent but pathologically different benign liver lesions: the first one (FNH) without a strong indication for surgery and the second one requiring surgery because of its uncertain diagnosis.

FNH has no recognized risk of malignant transformation or bleeding and usually has an uneventful course.Therapeutic abstention is usually recommended for asymptomatic patients with a definitive diagnosis[11].Surgical management is reserved for symptomatic patients or with diagnosis uncertainty despite a complete workup[12,13].Twelve cases of spontaneous rupture of FNH are described and considering these extremely rare events, conservative treatment is the actual wellestablished standard of care [English-language literature until 2019; NCBI.gov with terms “spontaneous; rupture; FNH].Close follow-up is however recommended for FNH more than 5 cm.Some authors advocate for upfront surgery with FNH larger than 5 cm[14-16].However, we do not recommend a surgical resection in our daily practice but advocate for a close follow-up strategy.In the present case report, the diagnosis of FNH of the segment III lesion was radiologically typical and in the absence of the HCA component, a 1-year MRI follow-up would have been recommended.

On the contrary, the risk of malignant transformation of HCA is 4%-5%.As reported by Sempouxet al[7], risk factors for complications of HCA (bleeding or malignant transformation) are the size (> 5 cm), male gender, activating mutation in β-catenin, and specific clinical background (glycogen storage disease, androgens, vascular diseases).The resulting recommendations for surgery are based on initial size (> 5 cm), imaging or histological signs of malignancy, size progression after OC discontinuation, and male patients.Selected patients and those who are not fit for surgery can benefit from embolization[17-19].When the diagnosis cannot be achieved with imaging, a percutaneous biopsy or resection may be required[20].

Moreover, Br?keret al[21] 2012 advocated the surgery for adenoma greater than 5 cm with patients who had planned a pregnancy.Our patient didn’t have a pregnancy plan but size and uncertainty of diagnosis were our principal arguments for surgery.

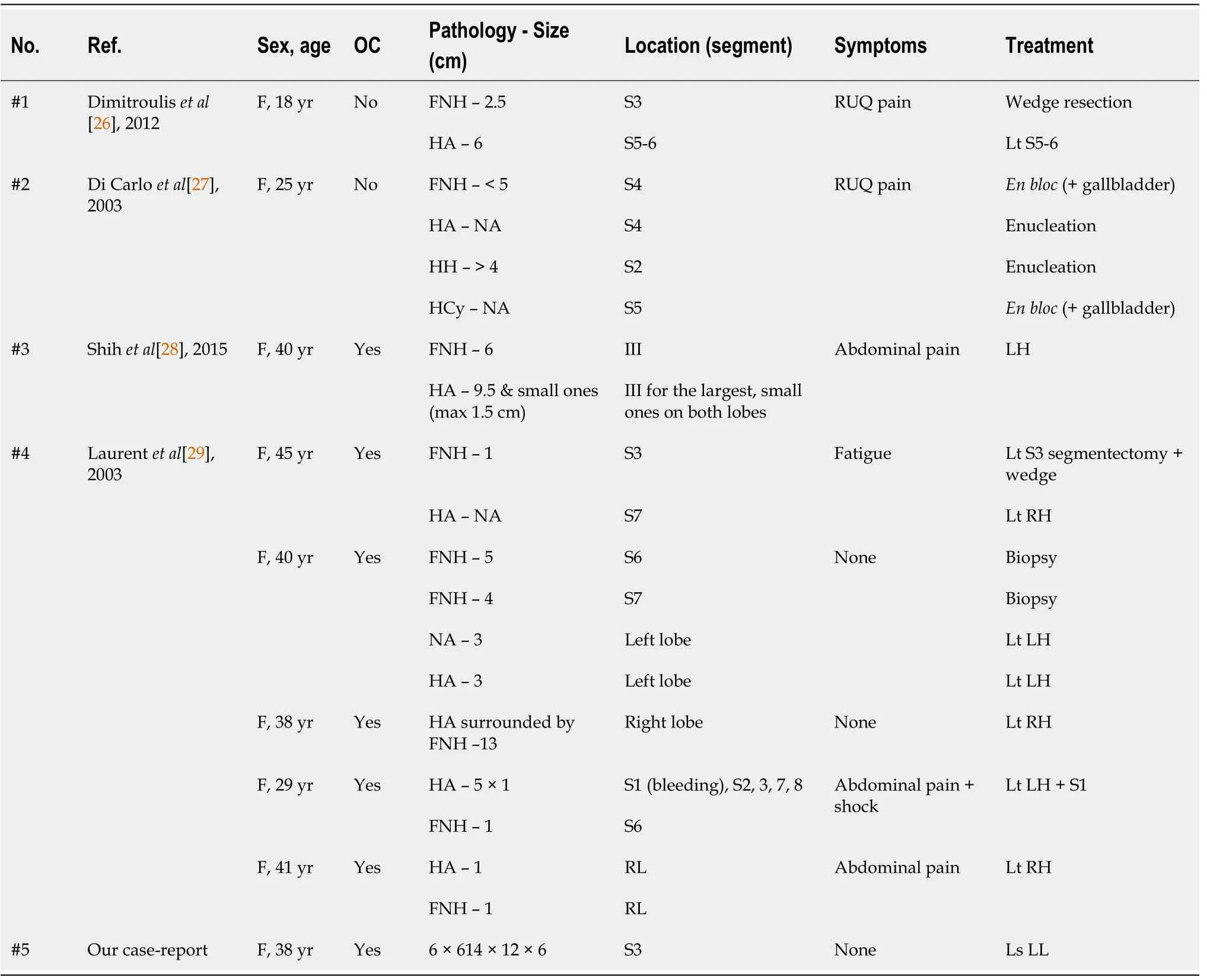

We made a literature review of the simultaneous cases of FNH and HA.Although there is some case reports in the eighties, the article was not available for consulting[22-25].Table 1 summarizes the other cases with enough data.

Table 1 Summary of current literature review

Case 1 was operated on because of the lack of obvious radiological evidence[26].The authors of case 2 don’t clearly explain the indication for the operative procedure but they interestingly explain the possible same pathophysiological etiology for 4 different simultaneous hepatic masses[27].

Shihet al[28] made a left hepatectomy for a case with common features between FNH and HA and operate for the uncertainty of diagnosis.

The French group of Laurentet al[29] found in their records 5 over 30 patients operated for “benign hepatocytic nodules" with simultaneous HNF and adenoma.All of them went under surgery when the radiology reports an HA or unidentified mass.The diagnosis of FNH was already known at the time of the surgical procedure except for one case where the FNH was too small[29].

Concerning the surgical technique, the laparoscopic approach is relatively recent.Unfortunately, Shihet al[28] didn’t report this in their paper although they did the same procedure for a similar patient.Despite the lack of high-level evidence data (randomized control trials, meta-analysis), current literature about laparoscopicvsopen liver surgery for benign tumors suggests an advantage for the minimal-invasive technique[30,31].On the other hand, evidence for laparoscopic malign liver resection is much more consistent.Furthermore, safety, feasibility, and long-term results confirmed the advantages of laparoscopy for malign liver tumors[32-34].

CONCLUSION

We hereby report a laparoscopic resection of a macro-adenoma associated with focal nodular hyperplasia.The review of the literature shows that the simultaneous presence of these two masses is rare and that every case must be discussed in a multidisciplinary board.Factors like age, pregnancy wish, size, and uncertainty of diagnosis must be considered for shared decision in the setting of a multidisciplinary team.The laparoscopic approach should be preferred as much as possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr.Giulia Piazza for her graphic representation of the case (Figure 2) which she has kindly drawn and for her courtesy in publishing it.

World Journal of Hepatology2021年10期

World Journal of Hepatology2021年10期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Coronavirus disease 2019 in liver transplant patients: Clinical and therapeutic aspects

- Clinical outcomes of patients with two small hepatocellular carcinomas

- Acute liver failure with hemolytic anemia in children with Wilson’s disease: Genotype-phenotype correlations?

- Machine learning models for predicting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the general United States population: NHANES database

- Impact of biliary complications on quality of life in live-donor liver transplant recipients

- Serum zonulin levels in patients with liver cirrhosis: Prognostic implications