Effectiveness of low vision aids in vision rehabilitation and improvement of reading speed in people with age-related macular degeneration

Mufarriq Shah1, Muhammad Tariq Khan

Abstract

?KEYWORDS:age-related macular degeneration; blindness; visual rehabilitation; low vision aids

INTRODUCTION

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a progressive ocular disorder, is a leading cause of blindness and vision impairment in aged population in high-income countries[1-3]. AMD is reported the second leading cause of moderate or severe vision impairment in global population in 2015[1]. World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 8.8 million people worldwide are blind or have severe vision impairment due to AMD. Blindness due to AMD varies from 3.98% in West sub-Saharan Africa to 19.53% in Eastern Europe[1]. AMD contributed to 9% of cases in people with blindness and vision impairment in Pakistan[4]. Global projected number of people with any AMD is 196 million in the year 2020, and is expected to rise to 288 million in 2040. Prevalence of AMD is 8.69% in the world and 6.8% in Asia[5-6]. The prevalence of AMD is higher in Europe than in Asia[5]. However, there will be greater number of people with AMD in Asia in 2040 due to increasing life expectancy and substantial increases in the population size which will results in an increase in the number of people with blindness and vision impairment[5,7-8].

AMD is a bilateral condition and affect central visionand central visual field. Vision loss due to AMD affects the individual’s capability to perform vision dependent tasks related to activities of daily living such as difficulty in reading, watching television and recognizing faces[9-10]. These disabilities have profound effects on quality of life of people with AMD[9,11]. Reading difficulty is one of the major complaints of people with AMD and improvement in reading performance is one of the main objectives of aged people for visiting rehabilitation services[12-15].

There is no treatment for AMD that can restore vision to the normal level.Therefore, the increasing prevalence and devastating consequences of AMD and the lack of effective treatment for people with AMD highlights the importance of vision rehabilitation[16-17]. The purpose of low vision rehabilitation services is to optimize the residual vision through the use of optical and non-optical low vision aids and modifications to the visual environment such as use of adequate lighting and contrast enhancement techniques[3]. Improvement in reading ability is one of the major outcome measure for examining the effectiveness of vision rehabilitation services[12-18]. However, there is a lack of systematic research about impact of vision rehabilitation on reading performance of people who want to read other than standardized text such as Arabic. The aim of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of low vision aids in vision rehabilitation and improvement of reading speed in a diverse group of people with AMD.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This hospital-based cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted on 44 people suffering fromvarious stages of AMD aged between 55-95 years. These people with AMD were referred to our Low Vision Clinic from various hospitals in the province for the provision of their first low vision rehabilitation services. Participants were enrolled consecutively in this study between January 2019 and December 2019. In Pakistan, low vision services are provided in the department of ophthalmology in tertiary care hospitals. The majority of these services are provided as mono-disciplinary under which low vision devices are prescribed without enough facilities for visual rehabilitation services. People have less awareness about low vision services. They use to go to ophthalmologists in secondary level hospitals from where ophthalmologists refer people who need low vision aids to low vision clinics in tertiary eye care hospitals. All participants included in this study underwent a standardized protocol of low vision assessment in our low vision clinic including history of each participant’s ocular and general health, assessment of visual functions, subjective and objective refraction, evaluation of magnification requirement, provision of low vision aids and measuring of reading speed before and after provision of low vision aids.

Distance visual acuity of each participants was measured first monocular then binocularly using the Bailey-Lovie LogMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution) test with the participant’s available refractive correction for distance vision[19]. The directional E LogMAR test was used for people unable to read English. VA was tested at 4 m and, if necessary, at 3, 2 and 1 m on each eye. DVA was classified and grouped into vision impairment [6/18>VA>6/60 (<0.54-1.0)], severe vision impairment [6/60>VA>3/60 (<1.0-1.3)] and profound vision impairment [VA<3/60 (<1.3)] according to classification system developed by the International Centre for Eye Health in collaboration with WHO[20].

For participants who could read English,Bailey-Lovie LogMAR chart for near vision in print sizes ranging from 1.1 LogMAR (5 m, 40 point) to -0.2 LogMAR (0.25 m, 2 point) [Bailey-Lovie Reading Chart Berkeley MN text version T1 School of Optometry, U.C, Berkeley, 1999] was used to assess their near VA and reading speed.

Though people in Pakistan and many other Muslim countries do not understand Arabic, they learn to read Quran, our religious book, which is in Arabic language. There is no s standardized test available for people who cannot read English and want to read Arabic. To assess the visual capacity for reading and measure reading speed of participants with AMD who do not understand English and need improvement in near vision to read Quran, passages from Quran in print sizes ranging from 5 m (40 point) to 1 m (8 point) and equal length of words were printed.

Near visual acuity (NVA) was divided into three groups; less than 3.2 m, 3.2 m to less than 1 m, and 1 m (newspaper size) or better and were recorded for each eye[4], “m” notation designates the distance (in meters) at which the object subtends an angle of 5min arc. Thus 1 m print size subtends 5min arc at one meter. The goal near visual acuity was defined on the basis of the need of the participant. The smallest print size read, the distance of eye from the print, equivalent viewing distance (EVD) and equivalent viewing power (EVP) for specification of magnification were recorded. Reading speed was calculated as words per minute (wpm) by the formula [correctly read words/reading time (seconds)] × 60. The number of wrongly read words were noted and subtracted from the total number of words of the text.

The magnification requirement for distance vision was chosen for the better-seeing eye for distance; similarly magnification requirement for near vision was calculated for the better-seeing eye for near vision. Various low vision aids such as telescopes, hand hold and stand magnifiers with and without illumination, selective absorptive filters for various wave lengths and closed circuit television were used during assessment. According to the magnification requirement for distance and near vision, the appropriate low vision aid was carefully tested and prescribed. Most of low vision devices (LVDs) are difficult to use for the first time due to decreased working distance and field of view. Therefore, all participants were instructed how to use LVDs for reading and were trained for 30-40min before reading speed with low vision aids was measured.

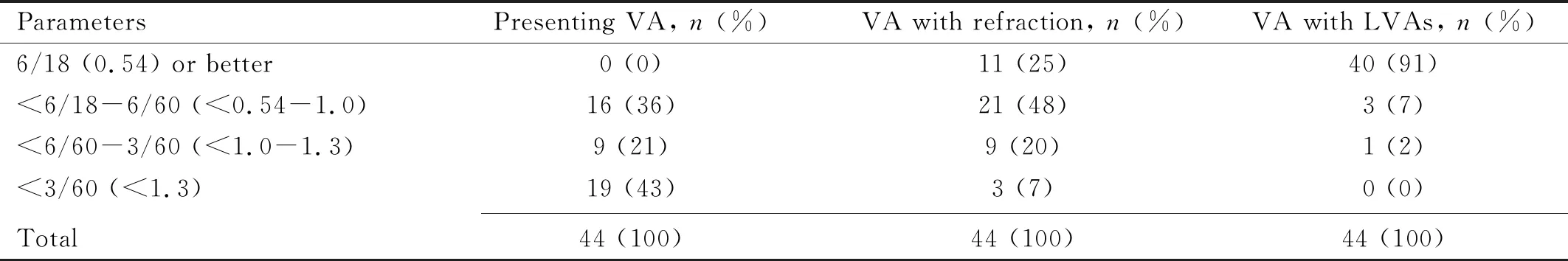

Table 1 Presenting VA, VA with refraction and VA with LVAs (n=44)

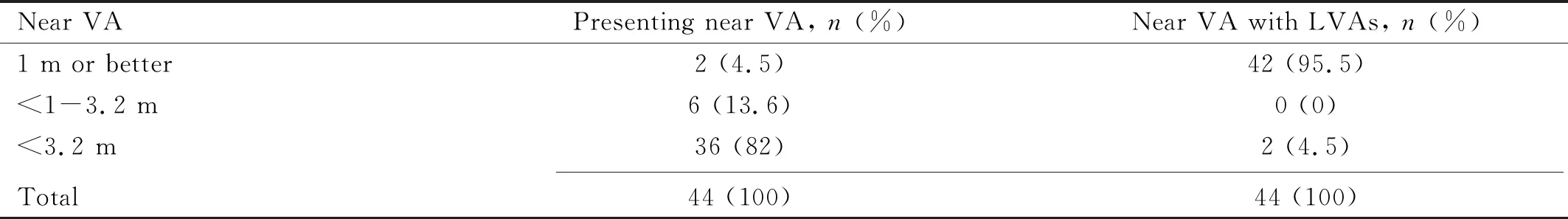

Table 2 Near VA at presentation and with LVAs (n=44)

StatisticalAnalysisAll data were obtained and recorded in a specifically designed data sheets and then transferred to SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 19 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for the purpose of analysis. Results are shown descriptively as mean values, standard deviation and range. Mann-WhitneyU-test was used to compare reading speed before and after the provision of low vision aids.P-values of less than 0.05 were considered as indicators of statistical significance.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hayatabad Medical Complex Peshawar. Study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards stated in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.Written consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

RESULTS

A total of 44 people with a high percentage of male (82%) with AMD referred for low vision rehabilitation were assessed in the low vision clinic and included in the study. Mean age was 73±10.8 years with minimum age 55 years and maximum age 95 years. Thirteen (29.5%) of the participants were educated and could read and write, 16 (36.4%) of the participants could read only while 15 (34.1%) of the participants were illiterate and they could not read or write. Among female participants five were illiterate and two could read and write. Among male, 15 participants could read only, 11 could read and write while ten were illiterate.

On presentation, 29 (67%) of the participants had distance visual acuity (DVA) 1.0-1.6 LogMAR (between 6/60 and 6/240) in the better seeing-eye. With adequate refraction this number was reduced to 20 (45.5%) due to improvement in DVA in nine participants. The mean distance visual acuity of the better-seeing eye for the whole group was 1.15±0.34 LogMAR (range: 0.5-1.6). The mean distance visual acuity with adequate refraction was 0.85±0.38 LogMAR. Mean improvement in distance visual acuity with adequate refraction was 0.298±0.225 LogMAR (P=0.000). Mean distance VA was enhanced to 0.19±0.24 LogMAR after provision of low vision devices (P=0.000). Mean improvement in distance visual acuity with low vision aids was 0.67±0.27 LogMAR (P=0.000). Visual acuity of better-seeing eye of all participants grouped into vision impairment [6/18 >VA>6/60 (<0.54-1.0)], severe vision impairment [6/60>VA>3/60 (<1.0-1.3)] and profound vision impairment [VA<3/60 (<1.3)] at the time of presentation and with low vision aids is shown in Table 1.

Mean spherical equivalent refractive errors were+0.98±5.18 DS and 1.09±4.5 DS in right eyes and left eyes respectively. Refractive error amongst the whole group ranged from -10.0 DS to +11.0 DS. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean spherical equivalent of refractive errors in right eyes and left eyes of participants (P=0.854). On presentation, only two (4.5%) participants had near VA of 1 m with their own glasses. With the provision of low vision aids 42 (95.5%) achieved near VA of 1 m. Near visual acuity person with their habitual glasses at presentation and with the provision of low vision aids is given in Table 2.

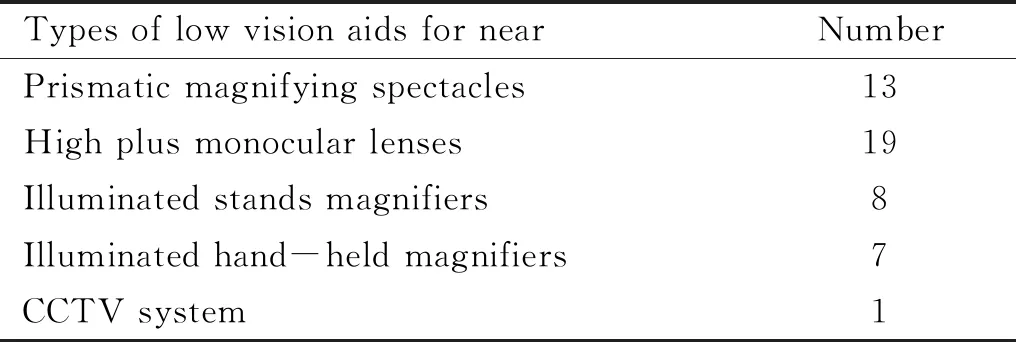

For distance vision, spectacles were prescribed to 43 participants. Monocular telescopes were prescribed to 15 participants. To perform near task, high plus monocular lenses were prescribed to 19 participants. Prismatic magnifying spectacles up to 8 dioptres with base in prism (Fonda glasses) were prescribed to thirteen participants. Devices prescribed for near vision are given in Table 3.

Table 3 Types of low vision aids for near

Two participants have NVA of 1 m or better but both of them were illiterate. Reading speed was not calculated in the group of illiterate participants (n=15) due to their inability to read any text. With the provision of LVAs reading speed was significantly improved (from 2.9±4.78 to 71.31±29.96 wpm) among the group of participants who could read and write (n=13) and the group of participants who could read only (n=16) collectively (P<0.001). Difference in means of reading speed without and with LVAs was 68.4±27.27 wpm. Prior to the provision of LVAs, there was no significant difference between the reading speed of participants in the group who could read and write and those in the group who could read only (P=0.199). The mean reading speed amongst the group of participants who could read and write and those who could read only was 4.62±6.18 wpm and 1.50±2.71 wpm respectively prior to provision of LVAs. However, after provision of LVAs, there was a significant difference in improvement in reading speed of participants who could read and write as compare to those who could read only (P<0.002) even though the NVA of the participants in both groups was enhanced to 1 m. Mean reading speed of participants who could read and write was improved to 90.31±32.0 wpm while reading speed of those who could read only was improved to 55.88±17 wpm with LVDs.

DISCUSSION

Findings from this study showed that provision of appropriate low vision aids (LVAs) play a highly effective role in vision rehabilitation of people with AMD. Most of the participants (91%) in our study achieved 0.54 LogMAR (6/18) or better with LVAs. These findings are consistent with the previous reports that vision rehabilitation services through the provision of adequate LVAs helps people with low vision to enhance their residual vision[12,21-22]. Reading ability in people with AMD is reduced and improving reading ability is a high expectation of people with reduced vision from vision rehabilitation services[12-13]. Results of this study demonstrated highly beneficial effects of use of appropriate LVAs in enhancing the reading performance with a significant increase in reading speed in people with AMD. The similar effectiveness of low vision aids in enhancing reading ability of people with low vision is reported in other studies[3,18,23].

There is no standard methodology about the selection ofthe type of low vision aids that should be prescribed to achieve maximal benefit from the residual vision in people with AMD. Some researchers reported magnifiers as the most frequently used aids for near vision among people with vision impairment[24]while other mostly prescribed high plus reading glasses for reading purpose[21,25]. In the current study mostly high plus monocular lenses were prescribed for near vision to participants with AMD. Though researcher claim that prisms have benefits in image relocation in people with AMD[26]. In this study, we did not prescribe prisms for image relocation or eccentricity in central scotomas but these were prescribed to achieve binocularity with high-power plus lenses in participants with DVA 0.9 LogMAR or better and who need to read comparatively large print size such as Arabic text at a greater working distance. We prescribed CCTV to one participant only while in other studies CCTV has been prescribed up to 42% in people with AMD where cost of CCTV is paid by health insurance providers[21,24,27]. This low number of CCTV in our study is due to non-affordability of the electronic low vision aids in our society because participants have to purchase low vision aids from market.

Improving reading performance is a major goal of people with AMD to achieve from vision rehabilitation services[14,25]. Several reports suggested various tests in different languages and methods of assessing reading performance[28]. These standardized reading tests are highly predictive of measuring reading performance but their limitation in people who cannot read these tests is also obvious from our study findings. More than two-third (70.50%) of the participants in our study could not read standardized text to assess their near vision for reading Arabic text or performing their near tasks other than reading purpose. In addition, all these tests and methods measure reading ability for meaningful text and reading speed is greatly influenced by cognitive factors[12]. In our study, participants in the group who could read only (n=16, 36.4%) wanted low vision aids for reading Arabic text but none of them could understand the meaning of Arabic. This is common in many Muslim countries. However, with the provision of low vision aids, reading ability was achieved in 100% of participants in this group. These participants noted problem in reading Arabic text and they visited low vision clinic for provision of aids to read.

A new aspect of our study is the use of Arabic text for measuring reading speed which cannot be compared with different standardized tests for reading because the difficulty of reading Arabic text cannot be compared with English text of the same length due to linguistic complexity. The important aspect worth highlighting is the participants’ goal of visit to our vision rehabilitation services. This group of participants wanted to re-start reading Arabic text and they achieved it through the use of appropriate low vision aids. As reported by several authors, near VA measured on simple test of letter acuity cannot predict reading performance[29-30]. Findings from our study also indicated that reading speed was not correlated to near VA in participants who could read and write and those who could read only. In our study, mean reading speed was improved to 90.31±32.0 wpm in participants who could read and write while 55.88±17 wpm in those who could read only. This shows that reading speed not only depends on near VA but also on the reader’s performance and cognitive factors. The reliability of our reading tests for these people who could only read but cannot understand what they read is questionable. To our knowledge, there has been no report of the use of any reading test for participants who could read a text but cannot understand the meaning of what they read. There is need of further research to optimize reliability of reading tests to equate reading performance across languages for multi-language participants.

A limitation of this study is that perimetry or scanning laser ophthalmoscopy to investigate the presence of central scotoma was not performed on these participants. Therefore, eccentric viewing techniques for reading speed were not evaluated. Though researcher reported a significant increase of reading speed in people with AMD and large absolute scotoma through training with eccentric viewing[30]. However, enhancement in reading performance with the use of appropriate low vision aids in most of participants in our study show that these participants have retained their central fixation. Participants (n=2) who could not achieved a significant improvement in reading speed with low vision aids were subjectively assessed if they could have any improvement in eccentric viewing but could not succeed. An important contributing factor among these two participants was denial to do effort for eccentric viewing. Providing appropriate low vision aids can play an effective role in vision rehabilitation of people with AMD and in improvement of reading abilities. Referral to low vision care services must be considered for people with low vision.