Gas Generation Mechanism in Li-Metal Batteries

Huajun Zhao ,Jun Wang ,Huaiyu Shao*,Kang Xu*,and Yonghong Deng*

Gas generation induced by parasitic reactions in lithium-metal batteries(LMB)has been regarded as one of the fundamental barriers to the reversibility of this battery chemistry,which occurs via the complex interplays among electrolytes,cathode,anode,and the decomposition species that travel across the cell.In this work,a novel in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry is constructed to differentiate the speciation and source of each gas product generated either during cycling or during storage in the presence of cathode chemistries of varying structure and nickel contents.It unambiguously excludes the trace moisture in electrolyte as the major source of hydrogen and convincingly identifies the layer-structured NCM cathode material as the source of instability that releases active oxygen from the lattice at high voltages when NCM experiences H2→H3 phase transition,which in turn reacts with carbonate solvents,producing both CO2and proton at the cathode side.Such proton in solvated state travels across the cell and becomes the main source for hydrogen generated at the anode side.Mechanisms are proposed to account for these irreversible reactions,and two electrolyte additives based on phosphate structure are adopted to mitigate the gas generation based on the understanding of the above decomposition chemistries.

Keywords

differential electrochemical mass spectrometry,gas evolution,lithium metal,lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide,oxygen release

1.Introduction

The ever-increasing energy consumption of the modern-day society demands a rechargeable battery of high energy density and long cycle life.[1-3]Lithium ion batteries(LIBs)have been dominating the markets of both electronics and automotive application.[4-6]However,the mediocre energy density of LIBs has imposed restrictions on the driving range of electric vehicles or standby time of electronics.Despite their historical frustrations,lithium-metal batteries(LMBs)are therefore revisited as the most promising alternative to LIBs,due to the theoretical specific capacity(3860 mAh g-1)of lithium,ten times higher than graphite.[7,8]When coupled with cathode materials based on Ni-rich layered oxides LiNixMnyCo1-x-yO2(NCMs),a high energy density LMB can provide the coveted driving range for electric vehicles(>500 miles per charge)and standby time for electronics(1 week per charge).[9]However,challenges always arise for such aggressive battery chemistries.On anode side,lithium metal can react with all known electrolyte due to its high reactivity,resulting in an extensive parasitic reaction accompanied by the evolution of highly flammable H2.[10]On cathode side,even though the theoretical capacity of layered NCMs is as high as≈280 mAh g-1,not all of the lithium can be extracted due to structural instabilities.Additionally,the intrinsically sloped potential profile desires very high potential to achieve full utilization of lithium.[11]In addition,layered NCMs with rising Ni-contents are more unstable.[12]As a result,the high voltage as well as the highly catalytic surfaces brought by Ni-rich chemistries induces oxidation of electrolytes,surface film formation,and transition metal dissolution,which ultimately deteriorate the cycle life.[11]Although extensive efforts have been made to introduce these layered oxides(NCMs)into commercial LIBs,there still remain many issues that must be addressed for their widespread applications.[13]Moreover,a lithium metal as anode would definitely introduce new variables,because a component in a battery is never isolated from other components.Among the numerous issues,gases evolution serves as an important indicator for the chemistry irreversibility.[14,15]Understanding what gas product is generated,and where and how it is generated constitutes a key knowledge needed for further development of this high energy battery system.

Gas generation in LIBs has been well studied.[16-20]Among the numerous gaseous species,CO2,CO,and H2are arguably the most notable.[21-24]The consensus reached in the community attributed H2as a product from trace moisture being reduced by anode.[25,26]However,as previously shown by Wu et al.and Novak et al.,H2quantity was much higher than expected from the moisture content.[27,28]Thus,the exact source for H2remains to be determined.On the other hand,CO2and CO are generally considered as products from the direct electrochemical oxidation of carbonate molecules,[19]while other mechanisms for CO2and CO were also proposed,including decomposition of native Li2CO3on surface of cathode[29]or chemical oxidation of carbonate molecules by the lattice oxygen released from xLi2MnO3·(1-x)LiMO2at high potentials.[30-32]Compared to LIBs,the investigations on the gas generation of LMBs are rather limited.[33]

In this work,an in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry(DEMS)was constructed to conduct in operando analysis on gas released from NCM-Li-metal cells during voltammetric scan as well as upon storage,where cathode materials of varying Ni-content(811,622 and 111)were used.We aimed at differentiating and determining the exact location and origin of H2and CO2generation and attempted to reveal the underneath mechanism how they were produced,so that an effective mitigation strategy could be designed.Based on the understanding,two electrolyte additives based on phosphate structure,triethyl phosphate(TEP)and tris(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)phosphate(TTFP),were tentatively used to curb the gas generation.

2.Result and Discussion

2.1.In Situ Gas Analysis

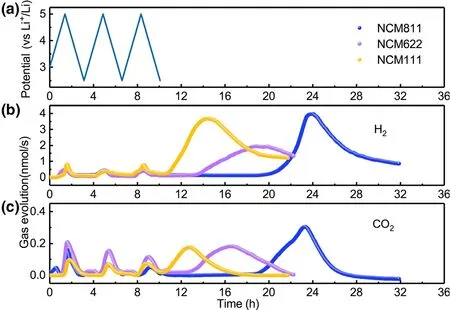

The gas evolution for all three NCMs-Li-metal cells was monitored for three cycles and then during subsequent storage at open circuit.The first three cycles of NCMs-Li cell and the corresponding CO2and H2evolution are depicted in Figure 1.One can observe similar increasing patterns of CO2and H2concentration for all NCMs-Li cells during the first three cycles,which correspond to the sharp increase in voltage from 2.5 to 5.0 V.It is apparent that CO2not only evolves at high cathode voltage when charging the cell;in fact,the maximum of CO2often occurs during discharge of the cell.H2dominates the whole gas generation speciation when compared to CO2during each cycle.However,its overall pattern is similar to that of CO2,implying that there must be a close correction between CO2and H2generation.Unlike most of the published research,[16,34]the DEMS cell was stored without any electrochemical treatment in our work after CV measurement and the gas was measured in operando by DEMS.An interesting feature is observed that a much more pronounced gas generation involving both H2and CO2is observed simultaneously during the open circuit storage,which has never been reported to our best knowledge.Mass production of gas during storage,especially combustible H2,would undoubtedly pose potential safety threat to battery users.

Figure 1.a)Cell voltage vs time for the NCMs-Li cells over three charge/discharge cycles.In situ gaseous evolution rate of b)H2and c)CO2 measured by DEMS as a function of time for the NCMs-Li cells.

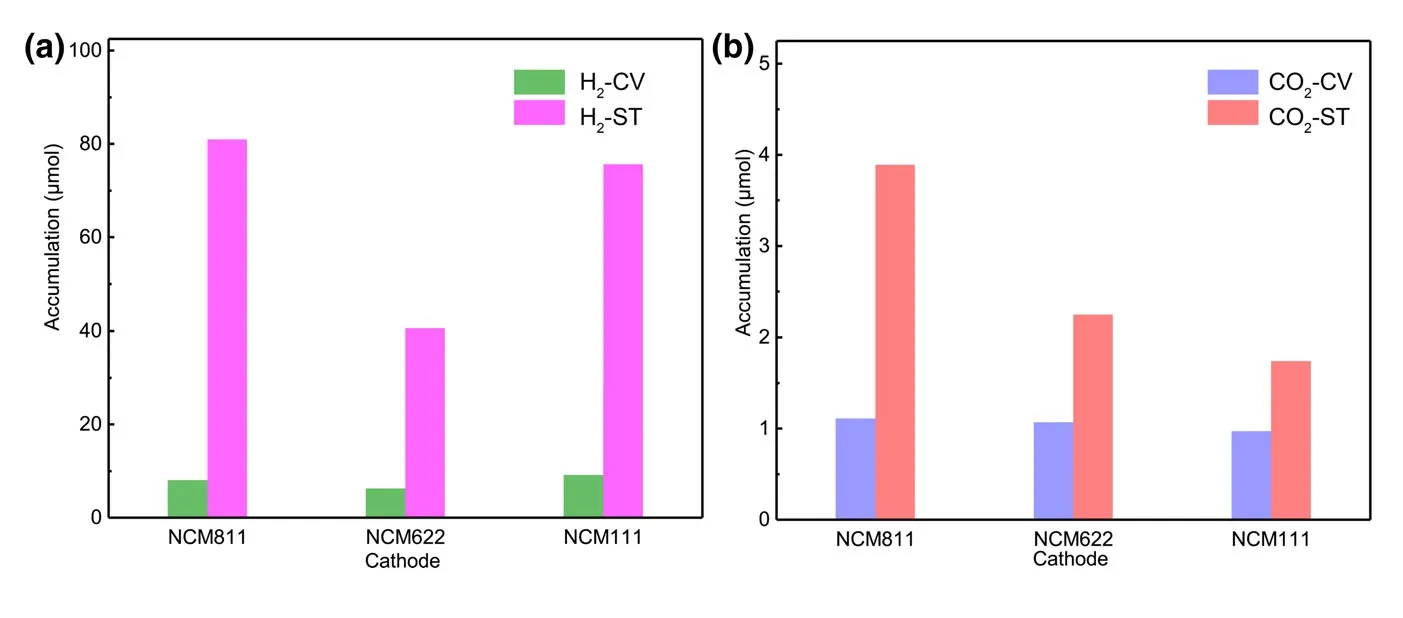

To better understand relationship between gas production and battery cycling,the amounts of H2and CO2in different periods were calculated quantitatively by using the calibrating gases(Figure 2).At least 40.66 μmol of H2could be obtained for NCM622-Li cell during storage.When the cathodes are NCM811 and NCM111,H2production during storage can even reach to 80.99 and 75.66 μmol,respectively.Considering the electrodes and other battery component were fully dried under the same condition before connecting to the DEMS,the trace moisture as the major source for H2must be reconsidered.[26]The calculation shows that 89.05 μmol H2requires 3.21 mg H2O in the cell,which would correspond to a 8917 ppm water level in 0.36 g of electrolyte.Or if H2O is from the electrode porosity,the value would equal to 10.7 wt.% of the 30 mg cathode.However,the water contents of electrolyte and cathode after drying used in this work are measured to be 5.6 and 37.8 ppm,respectively.Obviously,there is simply not enough water in the electrolyte or electrode to account for the amount H2observed,and other sources for H2must be taken into consideration.The electrolyte solvent that contains abundant hydrogen atoms attached to carbon should be the primary suspect.An electrolyte solvent can either be oxidized on the surface of cathode or reduced on metallic lithium anode,while chemically speaking H2can only be produced at anode.

Figure 2.Amounts of a)H2and b)CO2production during CV scan(H2-CV,CO2-CV)and storage process(H2-ST,CO2-ST)calculated quantitatively from DEMS.

In order to exactly determine where H2evolution occurs,we used LFP as a surrogate anode in place of lithium metal.The potential of the delithiated LFP resides at≈2.0 V versus Li/Li+(or-1.04 V versus SHE),therefore not only within the electrochemical stability window of the electrolytes,but also presenting a much less electrochemical reducing power toward the proton.[32,35]Such replacement brings visible change to the H2evolution,which remains negligible during the cycling(Figure 3);especially,when the CO2evolution reached its maximum rate during the storage,the synchronized evolutions between H2and CO2observed previously(Figure 1)completely disappear.This decoupling of H2evolution from CO2evolution in the presence of LFP anode provides a strong argument that H2must be generated on lithium-metal anode.On the other hand,the quantity of CO2evolved during every CV cycle and during storage(~1.57 μmol)is comparable to NCMs-Li systems,indicating that the production of CO2is not affected by the replacement of lithium with LFP.Thus,it can be concluded with confidence that CO2is mainly produced at the cathode side as a result of oxidative decomposition of electrolyte.

In order to further deconvolute possible contributions to H2from electrochemical reduction in bulk electrolyte components,we also replaced NMC cathode with graphite.One should note that a major uniqueness of such a cell(also known as“anode-half cell”in most literature)is the absence of a strong oxidation source,as the potential of graphite(≈0.01 V versus Li/Li+)is very close to that of lithium metal and cannot oxidize any electrolyte component.During the three CV cycles,3.60 μmol H2is observed(Figure 4),which is significantly lower than that from NCM811-Li system(80.99 μmol).In other words,when the oxidation source is removed,a major chemical source for H2source is gone.Such correlation strongly suggests that,although H2can only be produced at the anode surface,its real chemical source is the strongly oxidizing cathode.Therefore,the cross-talk between anode and cathode in a battery system must be held responsible for such correlation.On the other hand,since the H2evolution does not completely disappear with the replacement of NMC by graphite,there are additional although minor sources for H2generation as well,which should come from the direct reduction in protic species in the electrolyte,such as residual H2O or alcoholic impurities.However,it is the anode-cathode cross-talk that consistently provides the chemical source for the high quantity of H2generation as observed in Figure 1.

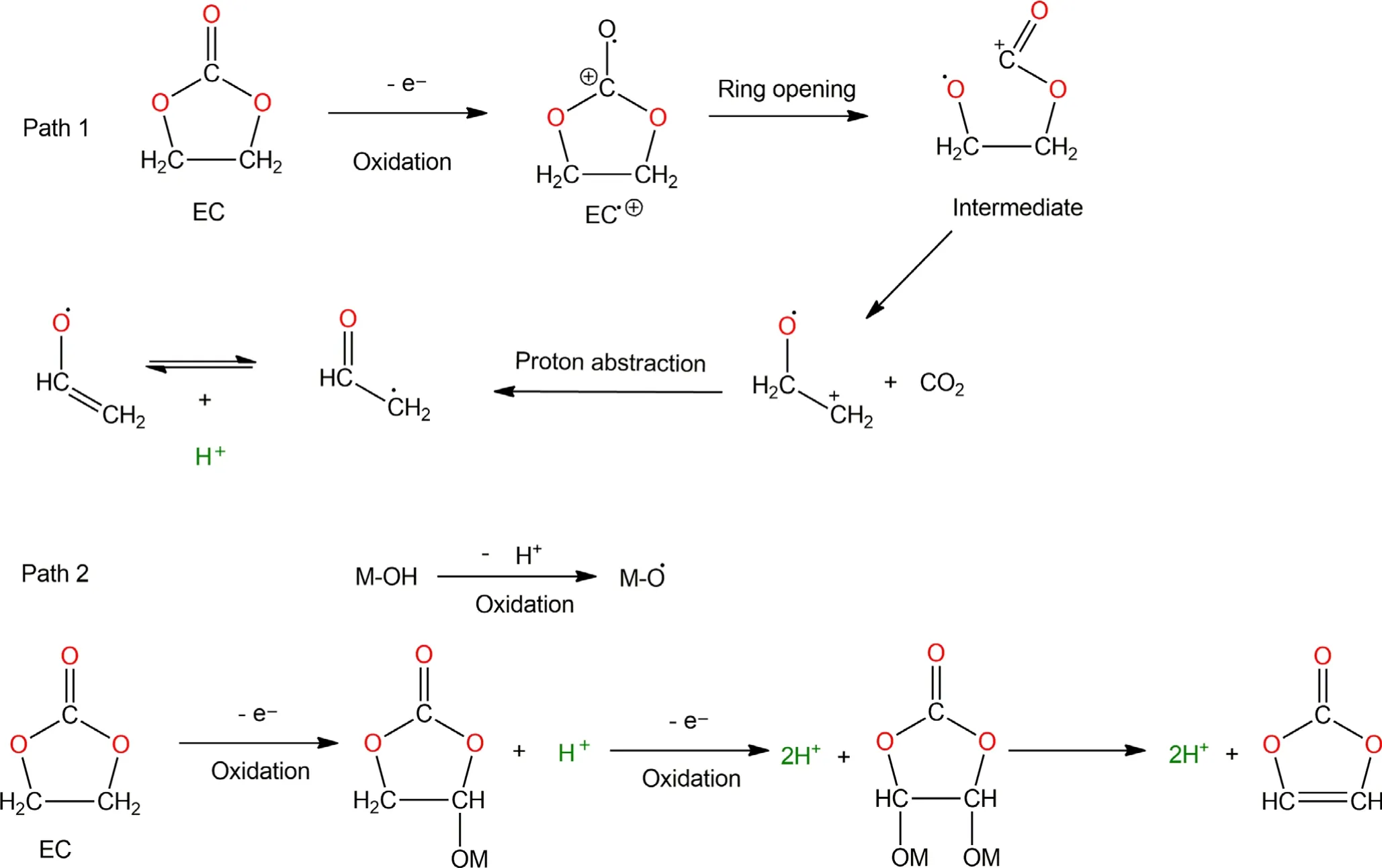

As indicated above,H2usually reached its maximum rate when the battery is charged to the high voltage region,along with the maximum of CO2evolution.This correlation strongly hints at an oxidative process related to H2evolution.A possible hypothesis that involves the generation and transport of protic species by electrolyte solvent(Sol-H+)is illustrated in Scheme 1,whose reaction paths were inspired by ab initio computational studies.[36-38]Based on the DEMS results,the formation of CO2is more energetically favorable than CO,especially in the presence of active O2,which will be discussed in next section.For an EC molecule to be directly oxidized,it must first undergo ring open to form cationic radical intermediates,whose fate will then be determined by which electrolyte component they interact.Path 1 and Path 2 lead to either CO2or CO formation accompanied by the formation of protic Sol-H+.The left cationic radical species like+CH2-CH2-O.tend to abstract a proton in principle to gain charge neutrality.Moreover,the cathode surfaces rich in hydroxyl groups(M-OH)may become a reaction center for the catalytic decomposition of electrolyte.[39]When the cell is in charged state,the M-OH group becomes being oxidized,with dehydrogenation and the formation of M-O.radical,which can further abstract H from other solvent molecules.Here,we propose that EC can catalytically lose a protic H by M-O.and form[EC-H]group bounded on cathode surface.Furthermore,[EC-H]may also lose another H along with the formation of vinylene carbonate(VC).[40]Eventually,the M-O.will finally combine with a H from solvent and reform MOH,thus completing a catalytic cycle.Hence,we speculate that the diffusion and subsequent reduction of the formed protic Sol-H+could be the chemical source for the significant H2evolution during electrochemical cycling.A similar reaction pathway could be proposed for diethyl carbonate(DEC)(Scheme S1),although Onuki et al.[41]showed that DEC was disfavored for such reactions when compared to EC even at high temperature.

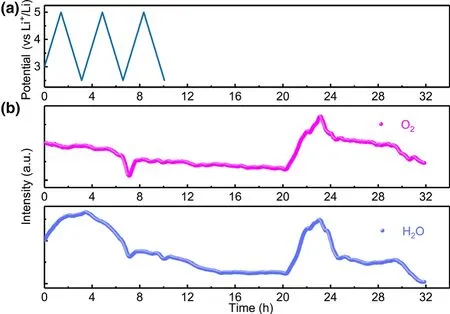

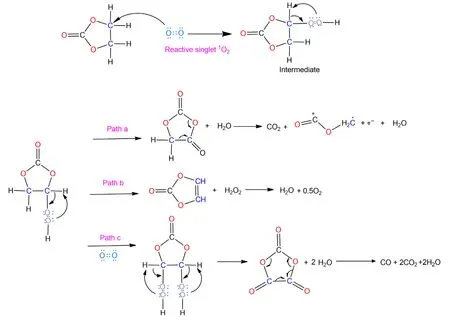

The proposed mechanisms are able to identify the H2source during voltammetric scanning.More interestingly,significant H2also occurs during the storage process at discharged state,which clearly points to other chemical processes contributing to the H2generation.It is reasonable to assume that at least one chemical reaction during storage keeps generating large amount of proton source,e.g.,H2O and Sol-OH,Sol-COOH,where Sol-stands for the electrolyte solvent.By monitoring H2O evolution pattern and comparing it with O2evolution(Figure 5),it is surprised to see both species H2O(g)and O2experience similar occurrence at about 20 h.In Novak’s previous work,oxygen release was observed directly earlier for Li1+x(Ni1/3Mn1/3Co1/3)1-xO2.[18]Here,in our work,in situ DEMS detects that O2evolution occurs during storage and its concentration increases first and then decreases continuously.The similar evolution patterns of H2O(g)to O2raise the suspicion whether these two species are correlated,i.e.,the released O2from NCMs leads to the production of H2O.Since EC remains stable in dry air,it should be noted that a pure chemical oxidation of EC by O2is only possible if O2is in its highly active state:e.g.,active atomic oxygen and singlet form.[42]Convincing experimental proof for such singlet1O2was reported earlier from NCMs and HE-NCM cathode materials when charged at high voltages.[43]Thus,we believe that the O2(triplet ground state)detected in our work during storage is attributed to the release of singlet1O2from NCMs;especially,when the singlet1O2is released from the lattice of NCMs,two main reaction pathways are supposed to be available for singlet1O2for further reaction:First,the singlet1O2would attack the electrolyte immediately accompanied by the evolution of H2O and other possible proton sources like Sol-OH,Sol-COOH,and second,it can recombine to become triplet ground state O2,which is subsequently carried to the DEMS by carrier gas.Here,it is believed that the evolution of H2O and other possible Sol-OH,Sol-COOH species should be attributed to the singlet1O2release that eventually results in the production of H2at anode side.Additionally,H2O would accelerate the hydrolysis of LiPF6with the formation of HF acid,which reacts with the SEI on the anode and induces more parasitic reactions.Moreover,during the first CV cycle,although the O2evolution is much lower than in storage,the H2O generation still occurs,which might be induced by the active singlet1O2.The O2evolution would result in the reaction with electrolyte,leaving little triplet ground state O2to be detected.The as-formed H2O would further contribute to the H2evolution at the anode surface.Of course,other mechanisms for H2evolution cannot be completely ruled out.Scheme 2 illustrates one possible mechanism for chemical decomposition of EC by singlet1O2along with the formation of H2O.

Scheme 1.Proposed mechanism for the electrochemical oxidation of ethylene carbonate(EC).

Figure 5.a)Cell voltage vs time for the NCM811-Li cell over three charge/discharge cycles.b)In situ gaseous evolution manners of H2O and O2 measured by DEMS as a function of time for the NCM811-Li cell.

Since H2evolution is the consequence of a complicated electrochemical and chemical process involving interplays of cathode,anode,and electrolyte components(solvents and salt anion),a critical stage b1eing the chemical oxidation of the electrolyte solvent by reactive singlet O2,Figure 2 shows that almost 90% of the entire gas(H2+CO2)can be generated during storage(chemical process).Obviously,the similar manners of CO2and H2evolutions in the entire process raise the question whether the CO2involves the same evolution mechanism as H2.Herein,a quantitative calculation corresponding to the experimental data on the CO2release was conducted,and it is found that 1.11,1.07,and 0.97 μmol of CO2are obtained for NCM811,NCM622,and NCM111-Li cells,respectively(Figure 2).Interestingly,the high similarity of CO2evolution rate of NCM811-Li,NCM622-Li,and NCM111-Li cells during electrochemical measurement seems to be contradictory to the work by Song and Shin et al.,who reported that the mixed-valence nickel ions served as key catalytic components to the electrolyte oxidation process.[44,45]In other words,we must answer the question whether the CO2evolution depends more on chemical composition of the cathode,or more on the operating voltage of the cathode.

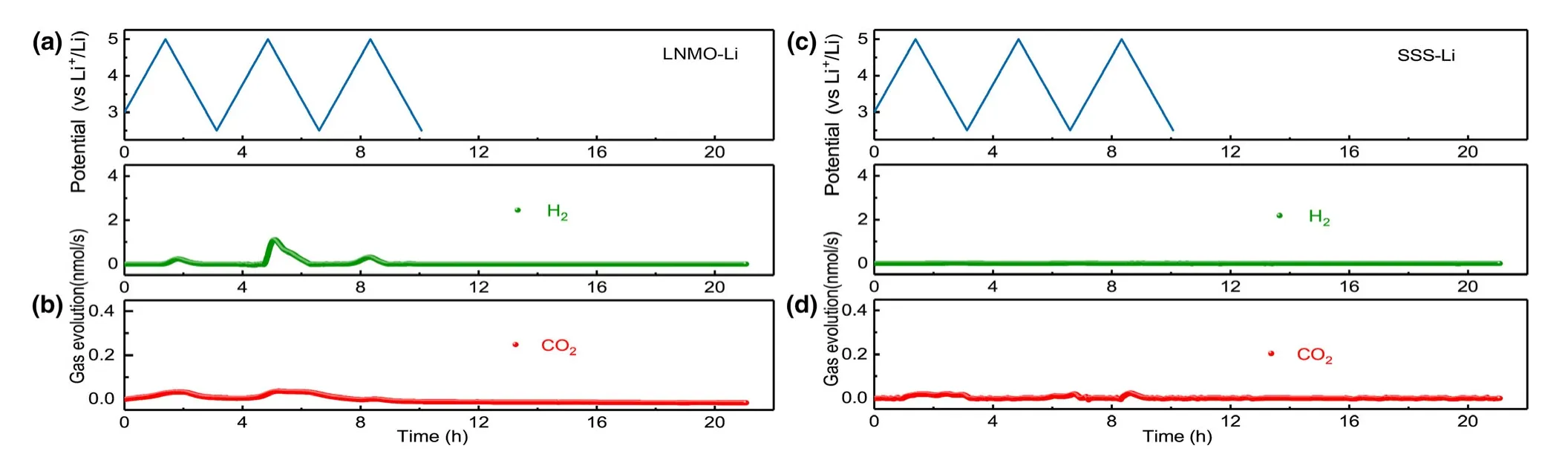

To address this question,we replaced NMC cathode with a cathode of higher voltage,nickel-manganese spinel oxide(LNMO).Considering that LMNO was charged to the same high voltage,the same gas generation should occur if the voltage rather than chemistry dictates the decomposition.But the contrary is observed:only 0.45 μmol CO2is detected during CV cycling of LNMO-Li cell(Figure 6),in contrast with the 1.11 μmol CO2observed in NMC811-Li cell.The limited amount CO2generated in this case is likely from the direct electrochemical oxidation of carbonate molecules.Negligible CO2and H2productions are also observed during the storage,confirming that the voltage is not the key factor.To further decrypt the contribution of voltage without interference from cathode chemistry,the DEMS experiment of stainless steel sheet-Li(SSS-Li)cell was conducted.Both CO2(0.24 μmol)production and H2(0.21 μmol)production are negligible after three cycles(Figure 6),indicating that the electrolyte is intrinsically stable toward stainless steel in the absence of cathode chemistry.The results further rule out the contribution of voltage to gas generation and confirm that the cathode chemistry instead should determine the gas generation and the subsequent electrolyte decompositions.

Figure 6.Cell voltage vs time for the a)LNMO-Li and c)SSS-Li cells over three charge/discharge cycles.In situ gaseous evolution rate of H2and CO2 measured by DEMS as a function of time for the b)LNMO-Li and d)SSS-Li cells.

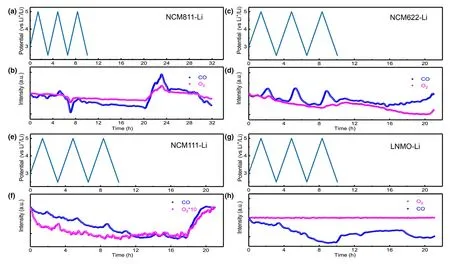

If the chemistry of cathode instead of voltage determines gas generation,then between NCM and LNMO,both of which contain Ni as the catalytic center,then why is there difference between these two in catalyzing the electrolyte decomposition?To resolve this difference,the CO generated in the presence of all these different cathode chemistries was investigated.Generally speaking,the evolution of CO2by oxidation of electrolyte is usually accompanied by CO,[46]which,in this work,maintains a similar evolution manner as CO2during CV measurement(Figure 7).The evolutions of CO are more obvious in NCM622 and NCM111-Li cells than in LNMO-Li cell.The low CO abundance is reasonable because that CO would immediately be consumed in the reaction with the highly active singlet1O2and form CO2.Based on this hypothesis,we compared the CO and O2evolution curves for all NCMs-Li and LNMO-Li cells,with the purpose to look for correlation between CO2/CO and O2evolution.In fact,at roughly the same time when the evolution of O2starts,a pronounced increase in CO evolution is observed for all the NCMs-Li cells,especially during the storage stage.Thus,the similar profiles of CO2/CO and O2serve as strong evidence that singlet1O2evolution contributes to the evolution of CO2/CO.

In contrast with NCMs-Li cells,the O2evolution curve for LNMO-Li cell remains unchanged during the entire process.The fact that hardly any O2and CO2can be detected at operating voltages as high as 5 V on LNMO surface,in sharp contrast with significant CO2formation synchronized with O2evolution on NCMs surfaces,supports the hypothesis that both CO and CO2are at least partially products of the chemical oxidation of electrolyte by the reactive singlet1O2released from the NCMs lattice.The difference in quantity of CO2detected during storage(Figure 7)might be due to the different tendency of various NCMs in releasing oxygen.The H2evolution detected in LMNO-Li cell during the entire process is calculated to be 4.15 μmol,which is much less than all the NCMs-Li cells,thus presenting another piece of evidence that oxygen release primarily contributes to the evolution of H2.

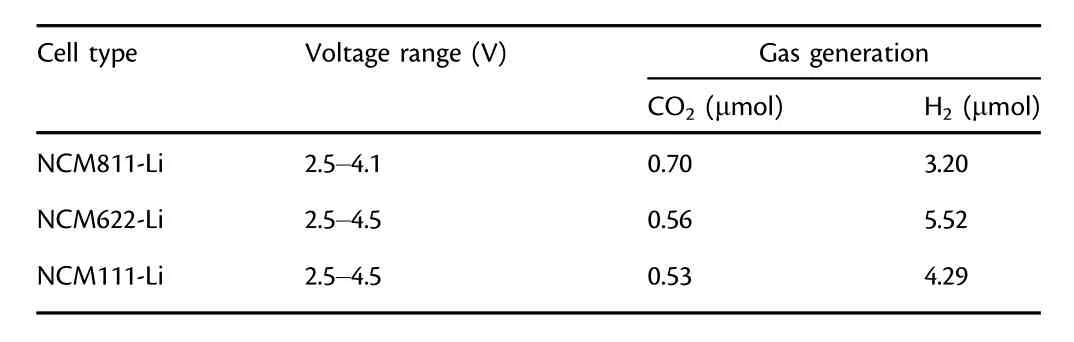

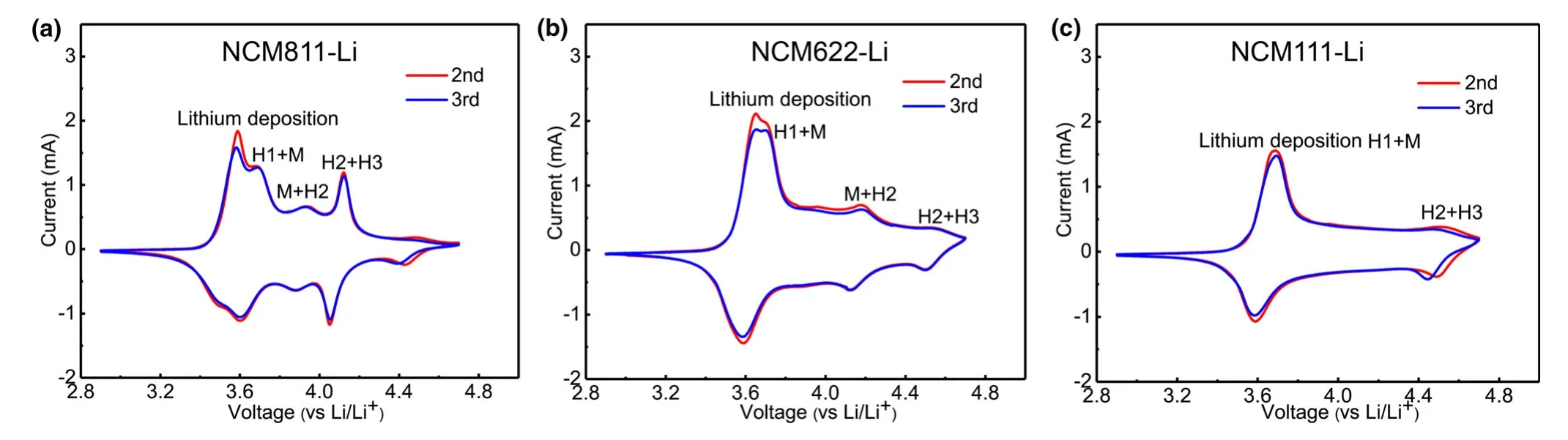

Oxygen release from lattice of NCMs has been regarded as a result of phase transformation from the layered oxide structure to spinel or rock salt phases.[14,43]The threshold voltage for oxygen evolution is closely related to the phase-transformation voltage.All three NCMs undergo a series of phase transitions during CV scan(Figure 8):the original layered structure(H1)changes into the monoclinic phase(M),which subsequently transforms into two other hexagonal phases(H2 and H3)in sequence.The two anodic peaks ranging from 3.50 to 3.80 V are similar for all three NCMs,and NCM811 exhibits more distinctive peaks,indicating its higher structural instability.The first peak is assigned to the lithium extraction from the cathode,and the latter mainly originates from the phase transition from layered structure(H1)to the monoclinic phase(M).However,the curve for NCM811 deviates substantially from that of NCM622 and NCM111.There are small anodic peaks at≈3.95 V versus Li/Li+and a large anodic peak at≈4.04 V versus Li/Li+,both of which are absent for the NCM622-Li and NCM111-Li,with the former attributed to the M-H2 phase transition and the latter to H2-H3.A broad peak around 4.18 V is visible for NCM622,which might indicate a M-H2 phase transition.For both NMC111 and NMC622,a small redox peak is observed near 4.50 V,which could correspond to a H2-H3 phase transition.Based on the above structural information,the DEMS experiment was conducted on NCMs-Li cells with different cutoff voltages(Figure S1).Under such circumstances,we observed fluctuated oxygen evolutions for all the three NCMs-Li cells during CV scanning and storage(Figure S2).The quantitative calculation of gas production was tabulated(Table 1).Surprisingly,when the NCM811-Li cell is cycled to 4.10 V,a comparable amount of CO2(0.70 μmol)as that at 5.0 V(1.11 μmol)is observed,which is significantly higher than LNMO-Li(0.45 μmol).Hence,oxygen release during phase transition indeed plays a critical role in electrolyte decomposition,while contribution from electrochemical oxidation of electrolyte to the gas generation is insignificant when the working potential exceeds 4.1 V.Meanwhile,for NCM622 and NCM111-Li cells,when the upper voltage is set to 4.5 V,the values are 0.56 and 0.53 μmol,respectively.The reason for the lower gas generation at 4.5 V than at 5.0 V may be due to little1O2released from NCM622 and NCM111.From the CO/O2evolution curves,it is observed that although a slight fluctuation of CO/O2occurs during CV scanning,an obvious increase during storage can be observed,leading to the significant evolution of CO2and H2evolution for all the NCMs,which once again gives strong evidence that the chemical oxidation of electrolyte by oxygen evolution from NCMs makes up significant contribution into the general process of electrolyte decomposition accompanied by gas evolution,while the electrochemical oxidation accounts for only a tiny fraction.

Table 1.Gas production during the first three CV cycles of NCMs-Li cells using 300 μL of 1MLiPF6(EC/DEC 3:7 wt./wt.)at different cutoff voltages.

Figure 7.a,c,e,g)Cell voltage vs time for the NCMs-Li and LNMO-Li cells over three charge/discharge cycles.b,d,f,h)In situ gaseous evolution manners of CO and O2measured by DEMS as a function of time for the NCMs-Li and LNMO-Li cells.

Figure 8.Comparison of CV curves at different cycle numbers for a)NCM811-Li,b)NCM622-Li,and c)NCM111-Li cells.

Scheme 2.Proposed mechanism for the chemical oxidation of ethylene carbonate(EC)by the active oxygen released from the oxide lattice of NCMs,along with CO2,CO and H2O evolution.

In summary,it can be concluded that the chemical oxidation of electrolyte by active oxygen release plays a critical role in H2and CO2formation,which is particularly pronounced during storage at discharged state.One possible mechanism is proposed here to account for the electrolyte oxidation partially based on the work with released reactive singlet1O2.[20,42]An electrophilic attack on the carbon by the singlet1O2leads to the formation of a peroxide group as the intermediate.In our opinion,three possible fates exist for the intermediate.Firstly,the unstable peroxide group can directly decompose to a carbonyl group along with the formation of one H2O molecule,which is consistent with the H2O evolution in Figure 4.The resultant molecule can further decompose into CO2and H2.C-O-C+=O,which in turn may further decompose to Sol-H+and CO(Scheme 1).Secondly,the formed intermediate may directly decompose to VC and H2O2,and the unstable H2O2gets oxidized rapidly,most likely leading to the formation of O2and H2O.Last,the formed intermediate can further be attacked by another1O2,forming another peroxide group and subsequently decomposing to CO2,CO and H2O.The formed water in this process can be reduced on the lithium anode,contributing to the release of H2.Although the predicted ratio of H2/CO2in this mechanism cannot precisely fit the observed ratio in Figure 2,considering that the chemical reactions in batteries involve complex processes and multiple species simultaneously,its validity still stands.For example,most of the formed CO2gas is scavenged by reactions with hydroxide and alkoxide ions,forming a thick,rigid,and Li2CO3-rich early interphase.[47]Also,the formation of H2O would accelerate the hydrolysis of LiPF6accompanied by the formation of HF acid,which might destroy the SEI and leave more fresh lithium exposed,leading to the reduction in more protic species like Sol-H+formed during the previous process.Of course,other synergetic mechanisms could also coexist.For example,according to the decomposition products detected by NMR spectroscopy,Grey et al.[48]proposed that the chemical oxidation of EC by singlet1O2would lead to the formation of glycolic acid(C2H4O3)and oxalic acid(H2C2O4),and these acid species(Sol-COOH)would be further reduced to H2.To this end,one principal mechanism proposed is that the chemical oxidation by possible singlet1O2results in the evolution of the gaseous H2and CO2,especially during the storage stage.Finally,an analogous mechanism between1O2and DEC is also proposed(Scheme S2).

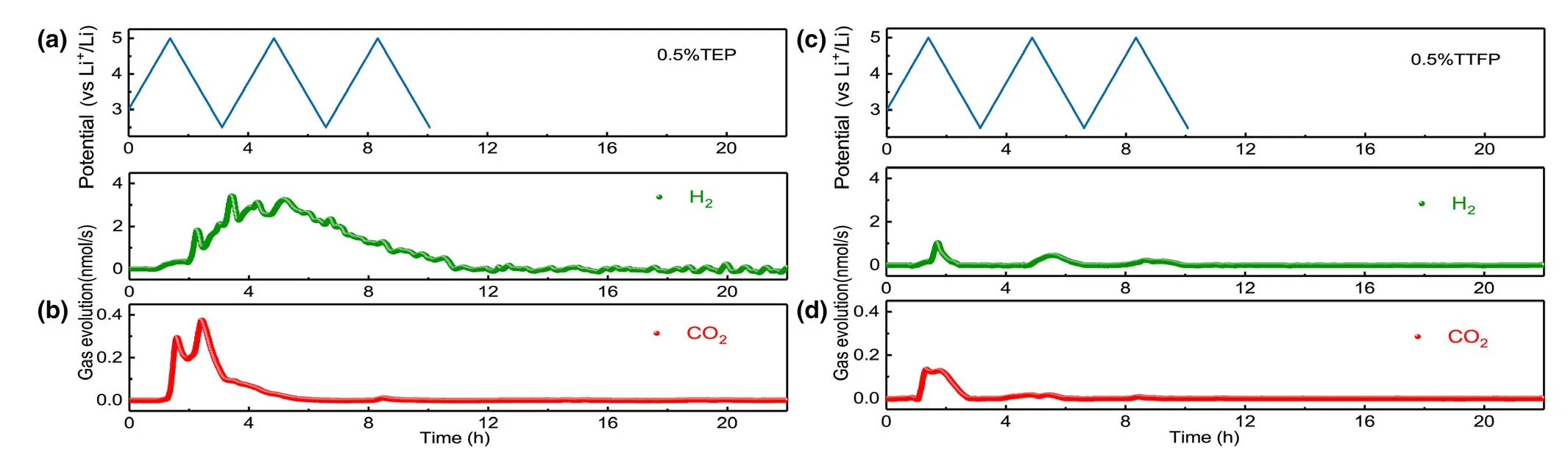

Based on the above understanding about the gassing mechanism,we tentatively adopted two electrolyte additives based on phosphate structure,triethyl phosphate(TEP)and tris(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)phosphate(TFEP),in the hope that the source of all gassing reaction,the active oxygen species,can be neutralized,because those phosphate molecules were more reactive at high oxidation potential due to the relatively higher energy level of their highest occupied molecular orbital(HOMO).[49]After incorporating these additives in the baseline electrolyte,the DEMS experiments were measured for NCM811-Li cells(Figure 9).For the electrolyte containing TEP,57.46 μmol of H2and 2.05 μmol of CO2evolution are clearly visible in the entire process.

Figure 9.a,c)Cell voltage vs time for the NCMs-Li cells using 0.5% TEP electrolyte and 0.5% TFEP electrolyte over three charge/discharge cycles.b,d)In situ gaseous evolution rate of H2and CO2measured by DEMS as a function of time for electrolyte with 0.5% TEP or 0.5% TTFP.

In contrast with the baseline electrolyte,there is no obvious gas behavior occurring in every CV scanning.It seems that the gas evolution curve due to electrolyte decomposition overlaps with the one from TEP electrolyte additive,which is reasonable because fluorinesubstituted solvents should bring a higher HOMO,owing to the high electronegativity and low polarizability of the fluorine atom.[50]As a result,much less H2and CO2evolution is observed in the initial CV scanning as compared to the baseline electrolyte as well as TEP-containing electrolyte.Furthermore,negligible CO2and H2are observed during the subsequent CV measurement and storage process,indicating an effective suppression gas evolution by electrolyte decomposition,which may be attributed to the characteristic of phosphates to capture active oxygen species.In fact,it is the special nature that makes all phosphates effective flame-retardants.This can be confirmed by the weakened O2evolution observed for both of TTFP and TEP electrolytes.[51](Figure S3)As indicated in Figure 8,there is no any gassing behavior observed during the storage process for both TEP and TFEP electrolytes.

The contribution of TEP and TTFP to the interfacial stability improvement in NCM811/electrolyte can be confirmed by further electrochemical characterizations.The NCM811 electrodes obtained from commercial NCM811-graphite pouch cell(1 Ah,Li-Fun Technology Corporation Limited)were subjected to charge-discharge cycling in NCM811-Li coin cells at 0.2C(1C=180 mAh g-1)with the cutoff voltage between 4.3 and 3.0 V.Figure S4 compares the evolutions of the discharge capacity curves and their Coulombic efficiency at different stages with increasing cycle numbers.Upon long-term cycling at 0.2C rate,the NCM811-Li cell using 0.5% TTFP demonstrates the superior performance.For the baseline electrolyte,the initial charge and discharge capacities are 264.16 and 214.7 mAh g-1,respectively(corresponding to an initial Coulombic efficiency of 81.3% ).With 0.5% TEP,the cell exhibits slightly improved performance,and the first charge and discharge capacities are 243.88 and 208.24 mAh g-1,respectively.However,the capacity retentions of cells using the baseline and 0.5% TEP electrolytes are inferior,and only 1.05% and 5.92% capacities are maintained after 50 cycles.It is encouraging that,just using 0.5% TTFP,it delivers a charge capacity of 250.99 mAh g-1and a discharge capacity of 208.05 mAh g-1,and the capacity retention is as high as 94.2% after 50 cycles.Additionally,the voltage curves of the cells using the baseline,0.5% TEP,and 0.5% TFEP cells are also evaluated.The cells with the baseline and 0.5% TEP electrolytes show prominent voltage decay as cycling,while the polarization is obviously reduced when the 0.5% TTFP electrolyte is employed.The superior performance for the cell containing 0.5% TTFP most probably demonstrates that the decomposition of electrolyte is prevented effectively,as indicated by the gas evolution measured by in situ DEMS.

3.Conclusion

In this study,we constructed a novel home-made DEMS system and applied it to investigate the gassing behavior of lithium-metal batteries using various cathode chemistries in operando.The dominant gaseous components were identified to be H2and CO2,and their respective sources were differentiated by constructing different electrochemical couples.The active oxygen species released from the layered NCM structure was identified as the chemical source for the generation of all gaseous products,while the direct electrochemical oxidation and reduction in electrolyte components were regarded as the minor contributor.The electrolyte additives based on phosphate structures with higher HOMO energy levels were tentatively used as scavengers for active oxygen,and the preliminary results appeared to be positive.

4.Experimental Section

Electrode and Electrolyte Preparation:For DEMS measurement,both positive electrodes(layered NCM with ratios among these three transition metals being 811,622 and 111,and spinel LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4)and graphite negative electrode consisting of 90% active material,5% conductive carbon,5% polyvinylidene fluoride binder(PVDF)were provided by Canrd(Shen Zhen,China).The slurry was mixed at 600 rpm for 24 h with N-methylpyrrolidone(NMP,anhydrous,99.9% ,Aladdin)as solvent.Then,the resulting slurry was dropped onto a H2325(Φ18)polyolefin separator(Celgard,USA),so that the evolved gas can diffuse through the pores of H2325 to the carrier gas.After drying at 45 °C under vacuum,the electrodes were dried at 95 °C under vacuum in a glass oven(G350Q,Vgreen,China)and transferred to a glove box(O2and H2O<0.01 ppm,Mikrouna,China)without exposure to ambient air.For the NCMs-LFP system,lithium iron phosphate(LiFePO4,LFP)electrode with 80% active material(31.6-32 mg cm-2)was electrochemically delithiated by charging an LFP/Li cell.Then,the delithiated LFP electrode was rinsed with dimethyl carbonate(DMC)inside an argon- filled glovebox prior to their usage as the counter electrode.

The baseline electrolyte consisting of 1M lithium hexafluorophosphate(LiPF6)dissolved in mixed solvents of ethyl carbonate(EC)and diethyl carbonate(DEC)(3:7,wt./wt.)was provided by Shen Zhen Capchem Co.Ltd.,China.Moreover,triethyl phosphate(TEP,Aladdin,99.7% )and tris(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)phosphate(TTFP,Aladdin,96% )were selected as electrolyte additives and were used at 0.5% (by weight)in baseline electrolyte to study their influence on gaseous behavior and cell performance.All the electrolytes were prepared in a highly pure Ar- filled glovebox(Mikrouna,China),where water and oxygen contents were controlled to be around 0.01 ppm.

In Situ DEMS Gas Analytics:The gas generation behavior was investigated by a home-made differential electrochemical mass spectrometry(DEMS)system with inert argon(Ar,99.999% )as the carrier gas.The DEMS experiment was designed and performed with NCMs,LNMO,graphite as prepared above as the cathodes,and metallic lithium as the anode.The custom cells were assembled inside an Ar- filled glovebox by staking the cathode electrode(18 mm,diameter),fiberglass membrane separator(GF/D,GE Healthcare Life Sciences,Whatman,90 mm diameter),and anode electrode(15.6 mm diameter)above each other.Three hundred microliter electrolytes was used.The cell was equipped with a gas inlet and outlet.After connecting to the potentiostat(CHI660E Chinstruments,China)and mass spectrometer system(HPR20,Hiden Analytical Ltd.,UK),the cell was purged by Ar for 30 min to remove the contaminations.The gas flow was controlled by a mass flow controller(EL-FLOW,Bronkhorst,Germany)and set to 1.0 mL min-1.The cell was then kept at open circuit voltage for 1 h to ensure a signal equilibration prior to the measurement.

The DEMS signal intensity data were automatically output by the instrument in two types:“faradaic current”and “concentration percentage,”which were all quoted as“intensity”in this work,unless otherwise specified.To convert the ion current of the evolution gas into concentration rate(nmol s-1),all mass signals of the measured gas(H2at m/z=2,CO2at m/z=44,CO at m/z=28,C2H4at m/z=26,O2at m/z=32,H2O at m/z=18)were normalized to the ion current of40Ar(I40),i.e.,(Iz/I40),so that signal fluctuations due to pressure and temperature changes during the measurement can be circumvented.Then,the evolution rate of the target gas was obtained by multiplying Iz/I40by the flow rate of the carrier gas(1.0 mL min-1).Specially,CO(I28)has no unique m/z,because both C2H4and CO2make contribution to this ion current I28.The fraction of signal on channel I28stemming exclusively from CO,i.e.,I28(CO)could be calculated through the following formula:I28(CO)=I28-1.59·I26(C2H4)-0.14·I44(CO2),where 1.58 and 0.14 are the fractions of I26(C2H4)and I44(CO2)on channel m/z=28 compared to their unique signals on channel m/z=26(C2H4)and m/z=44(CO2),respectively.These factors were obtained from the instrument’s own database.

Electrochemical Measurements:DEMS cell was electrochemically controlled with a CHI660E potentiostat.The cells were charged from 2.5 to 5.0 V versus Li/Li+for the NCMs-Li system and from 2.5 to 0 V versus Li/Li+for the AG-Li system with a scan rate of 0.4 mV s-1.The cycling performance of NCM811-Li coin cells executed in the mode CC/CV(constant current/constant voltage)in the voltages range 3.0-4.3 V versus Li/Li+at a current density of 0.2C(1C=180 mAh g-1).The CV of NCMs-Li coin cells was conducted with an CHI660E potentiostat at a scan rate of 0.05 mV s-1.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial supports from the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province(2020B090919001),Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Solid-State Batteries(ZDSYS20180208184346531),Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Energy Materials for Electric Power(2018B030322001),and Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Joint Laboratory for Photonic-Thermal-Electrical Energy Materials and Devices(2019B121205001).All the authors discussed the results and contributed to writing the manuscript.The authors sincerely acknowledge professor Zhangquan Peng for his technical support for the construction of the differential electrochemical mass spectrometry system.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Energy & Environmental Materials2022年1期

Energy & Environmental Materials2022年1期

- Energy & Environmental Materials的其它文章

- Introduction of Frontier Outlook

- Sn Alloy and Graphite Addition to Enhance Initial Coulombic Efficiency and Cycling Stability of SiO Anodes for Li-Ion Batteries

- Biomass Template Derived Boron/Oxygen Co-Doped Carbon Particles as Advanced Anodes for Potassium-Ion Batteries

- A Stretchable Ionic Conductive Elastomer for High-Areal-Capacity Lithium-Metal Batteries

- Understanding the Coffee ring Effect on Self-discharge Behavior of Printed micro-Supercapacitors

- Directional Oxygen Functionalization by Defect in Different Metamorphic-Grade Coal-Derived Carbon Materials for Sodium Storage