Expression of Thioredoxin System Protein lnduced by Silica in Rat Lung Tissue*

GUAN Yi, LI Gai, LIU Nan, WANG Yong Heng, ZHOU Qiang,4, CHANG Mei Yu,4,ZHAO Lin Lin, and YAO San Qiao,4,#

Silicosis, a potentially fatal global occupational disease, is characterized by progressive deterioration of pulmonary function and irreversible fibrosis resulting from crystalline silicon dioxide or silica inhalation. Extensive pieces of evidence[1-3]manifest that inhaled silica particles could directly or indirectly cause excess generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which plays a key role in the pathogenesis of silicosis. In order to maintain the cellular redox balance, the main function of thioredoxin (Trx)/thioredoxin reductase (TrxR)systems is to scavenge the ROS. TrxR, as a reductase of Trx currently known only, has the function of antioxidation and scavenging free radicals[4]. In addition, recentin vitrostudies demonstrate that Trx interacts directly with and inhibits the activity of apoptosis-regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1)[5]. The damaged cell of lung tissue caused by ROS may be an important link to ASK-1 triggered cell apoptosis. Zhu et al.[1]reported that silica could aggravate oxidative stress and promote the development of silicosis in rat lungs after silica exposure by downregulating the expression of TrxR and poor Trx activity. The specific mechanism of imbalance of reduction/oxidation status in silicosis is poorly understood. Our previous studies[6]demonstrated that oxidative stress in rats induced by silica leads to increased peroxiredoxins(Prxs) protein reactivity to resist oxidative stress, and Trx as an electron donor is functionally associated with Prxs. Hence, we propose a hypothesis that silica exposure may lead to the disturbance of the function of the Trx/TrxR system, contributing to further oxidative damage.

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Research Committee of North China University of Science and Technology,Hebei, China (certificate number: SYXK-Ji 2010-0038). Silica particles, < 5 μm in size, ≥ 99%, Sigma.Scanning electron microscopy of silica particles exhibited a relatively irregular morphology and more obvious aggregation phenomena. The peaks of the silica particle size were distributed at 2,763 nm,measured by a granulometer. Sixty-four Sprague-Dawley male rats (Specific-Pathogen-Free, six weeks old and weighing 180–220 g) were purchased from Beijing Weitong Lihua Experimental Animal Co. Ltd.Rats were maintained in a standard housing condition and had free access to standard rat chow and water. After one week, rats were randomly divided into the following two experimental groups:1) saline control group: rats received 1 mL of 0.9%saline by intratracheal instillation; 2) Silicon dioxide(SiO2) group: rats were exposed to SiO2at different times following a single instillation of silica suspension (1 mL of 50 mg/mL per rat) in the trachea. Animals were sacrificed on 7, 14, 21, and 28 d after silica instillation. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid(BALF) was collected. Serum was separated, placed in a centrifuge tube, and stored at ?80 °C. The lungs were removed, rinsed with saline, and weighed after drying on a filter paper to record gross pathological changes. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and Masson’s trichrome staining were used to detect histological changes, and the degree of pulmonary fibrosis was observed under a light microscope.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)was used to compare the differences among groups.P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0(SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

In this study, four time points in the rat model were used: 7, 14, 21, and 28 d post silica exposure to evaluate the pathological process of silica exposure(Figure 1A). Silicosis is characterized by the formation of silicotic nodules and extensive pulmonary fibrosis, causing pulmonary tissue edema due to the formation of collagen fibers, resulting in increased weight of the lung parenchyma. Our results verified that the lung coefficients at each time point were significantly higher than the control group (P< 0.01) (Figure 1B). Subsequently, the successful establishment of the silicosis model in rats was confirmed by observing morphology and pathological changes in lung tissues with H&E and Masson’s staining. The H&E staining results showed that an inflammatory reaction appeared on the 7th d, and multiple cellular nodules were visible in lung tissue on the 14th d. The multiple nodules were fused on the 21st d, and fibrous-cellular silicotic nodules with diffuse interstitial fibrosis were observed on the 28th d in rats (Figure 1A). Masson’s staining showed: red collagen fibers, green muscle fibers, cytoplasm, and red blood cells. This analysis revealed interstitial fibrosis with massive collagen deposition in the lungs of silica-exposed rats, and the changes were more apparent during prolonged exposure to silica (Figure 1A, D). In addition,hydroxyproline (HYP) is a major component of collagen, and its abundance is a critical marker of collagen metabolism[4]. The HYP content in lung tissue of rats exposed to silica was determined to further explore the degree of collagen deposition and the development of pulmonary fibrosis caused by silica. We found that HYP contents were significantly increased on 14, 21, or 28 d after silica instillation (P< 0.01) (Figure 1C). The result is consistent with the histopathological findings of the current study.

Figure 1. Pathological features in lungs induced by silica exposure. (A) H&E staining and Masson’s staining for pathological changes and accumulation of collagen changes in rat lung caused by silica (Scale bars 100 μm). The black arrows indicate distributed cellular nodules. Blue arrows indicate granulation,swelling, and fibrosis. Red arrows indicate collagen. (B) Wet lung-to-body weight ratio. (C) Content of HYP in lung tissue of rats. (D) Histologic assessment of fibrosis by quantitative image analysis and calculate percentages that are the areas of collagen to the area of the lung tissue. Values of all histograms were mean ± SD (n = 8); statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.01 vs. control, #P <0.05 vs. 7 d SiO2 group. HYP, hydroxyproline.

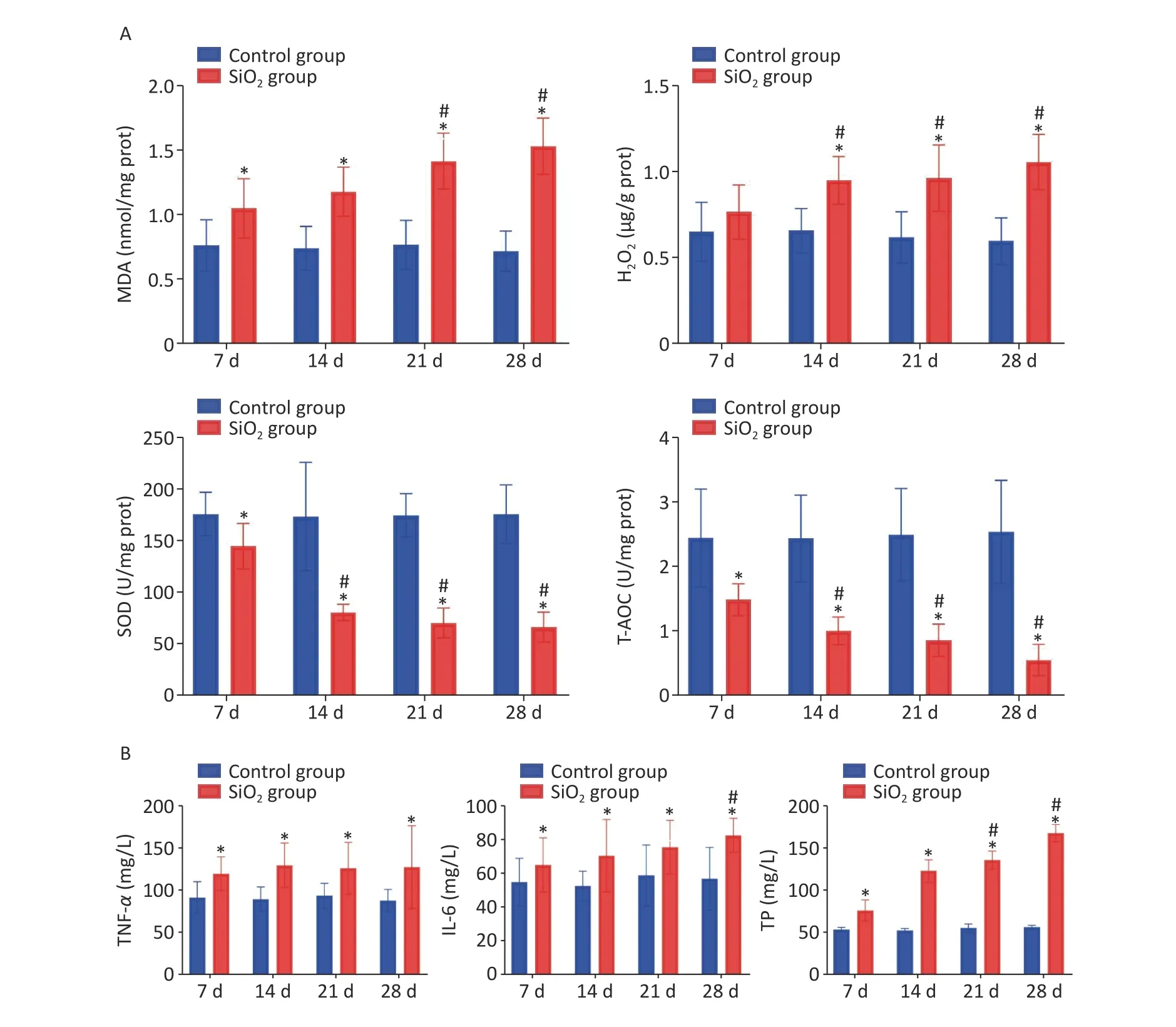

One of the major hypotheses regarding silicosis is the ability of the silica to induce oxidative stress, and ROS-induced lipid peroxidation is commonly assessed by measuring concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)is a reactive oxygen species, an intermediate product of oxidative metabolism. It can cause lipid peroxidation and deoxyribonucleic (DNA) damage in cells when H2O2concentration is accumulated to a certain extent[7]. Oxidative stress is also evidenced by increased expression of antioxidant enzymes,including superoxide dismutase (SOD) and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC). SOD can inhibit the peroxidation of free radicals, affect the cellular capacity to scavenge free radicals, and regulate oxidative stress[8]. T-AOC can promote the removal of H2O2and free radicals. We have observed that the MDA content was markedly increased during the four stages of exposure to silica (P< 0.05).Correspondingly, the H2O2level on days 14, 21, or 28 post instillation also showed a statistical increase in the SiO2group compared to the control group (P<0.05). Moreover, the activity of SOD and T-AOC was markedly lower in lung tissue of rats in the SiO2group than in the control group (Figure 2A). It is shown that the silica exposure disturbs the oxidant–antioxidant balance systeminvivoso that the body produces a large amount of ROS and free radicals and consumes a large number of corresponding antioxidant enzymes, which eventually leads to the decline in the defense mechanism of the body, antioxidant damage, and the oxidative stress reaction in the lungs, as supported by Nardi et al.[9].

Figure 2. Effect of silica on the content of MDA, H2O2, T-AOC, and SOD in lung tissue, and levels of TNF-α,IL-6, and TP on BALF. Values of all histograms were mean ± SD (n = 8); statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.01 vs. control, #P < 0.05 vs. 7 d SiO2 group. MDA, malondialdehyde; H2O2,hydrogen peroxide; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6, interleukin-6; TP, total protein; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

In addition to oxidative stress, inflammation has been reported to be a contributing mechanism of silicosis. The levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in BALF were evaluated to determine whether silica could induce inflammation,and we found that TNF-α was produced at an early stage of the inflammatory process in the SiO2groups, peaked on 14 d following instillation, and remained at a higher level, compared to levels in the control group, which was consistent with the literature[10]. Concurrently, the levels of IL-6 in BALF increased following silica exposure and significantly increased with the extension of exposure time.Likewise, exposure to silica could cause changes in biochemical composition. Silica exposure resulted in significantly enhanced levels of total protein (TP) in BALF as the time points progressed compared to the control group (P< 0.05) (Figure 2B).

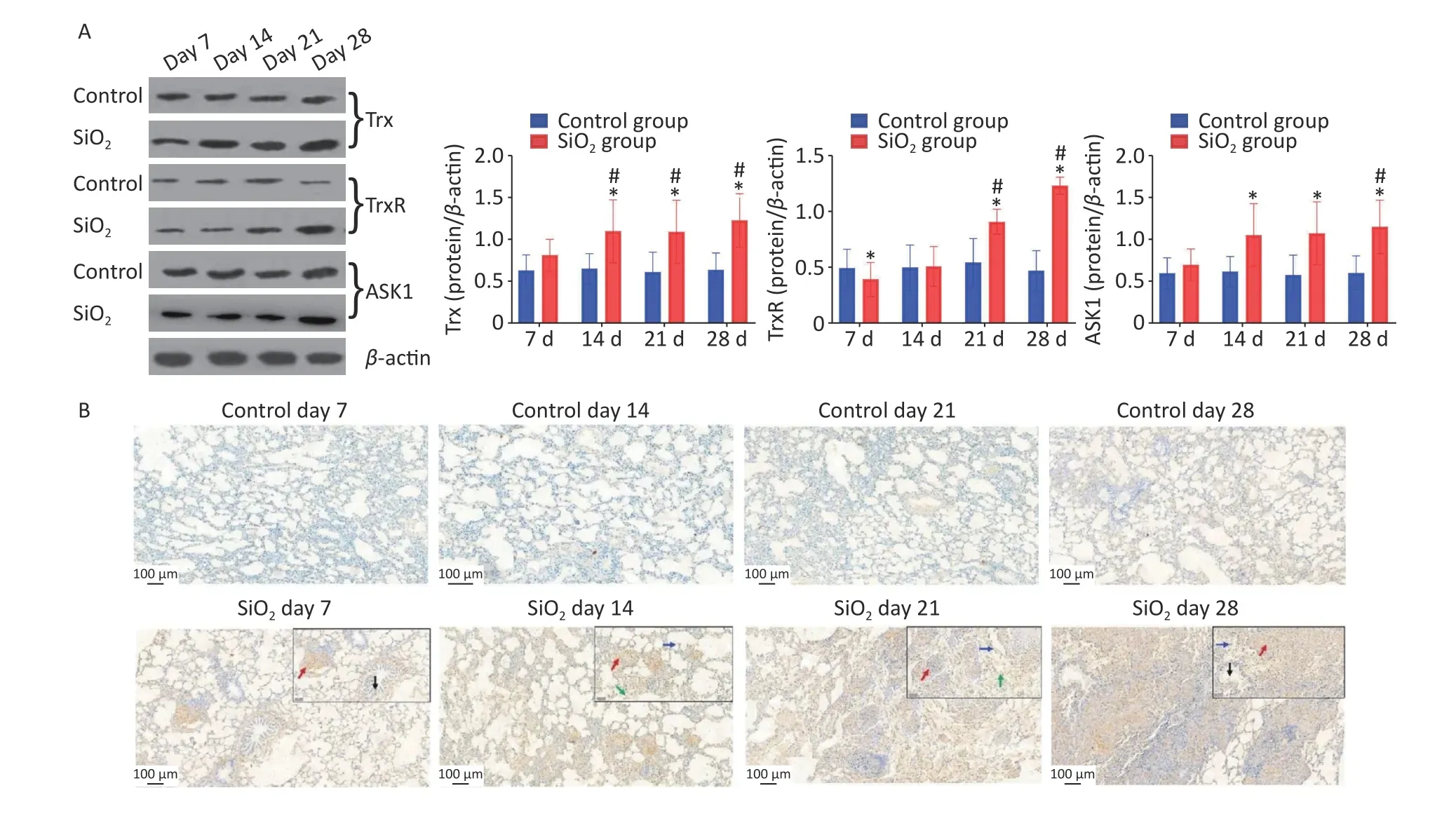

Besides that, we also explored whether the ASK-1 and the antioxidant system of Trx/TrxR play a role in silica-induced oxidative stress. ASK-1 is combined with its intrinsic inhibitor, Trx, under normal static conditions, and its activation is blocked. However,the molecular association between Trx and ASK-1 is impaired when challenged by harmful stimuli. Yu et al.’s results showed that upregulated TNF receptorassociated factor 1 impaired the association between Trx and ASK-1, which eventually triggered NF-kB-mediated inflammation[5]. In the present study, we have extended these findings to an invivomodel of silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis (Figure 3A). The findings showed that the protein expressions of ASK-1 and Trx in rat lungs were significantly increased on 14 d post silica exposure by western blot analysis. Moreover, we observed a potent downregulation of TrxR protein in the presence of silica on 7 d and upregulation on 21 d;the decrease of TrxR expression at the early stage corroborated with Zhu et al.[1]. We speculate that silica could aggravate oxidative stress by suppressing TrxR expression during the early days, which may explain the observation that TrxR was downregulated in lung tissue from silica-exposed rats on 7 d. With time, the TrxR protein expression(regulate the redox imbalance caused by TRX and ASK1) was compensatory increased on the 21 d in the SiO2group.

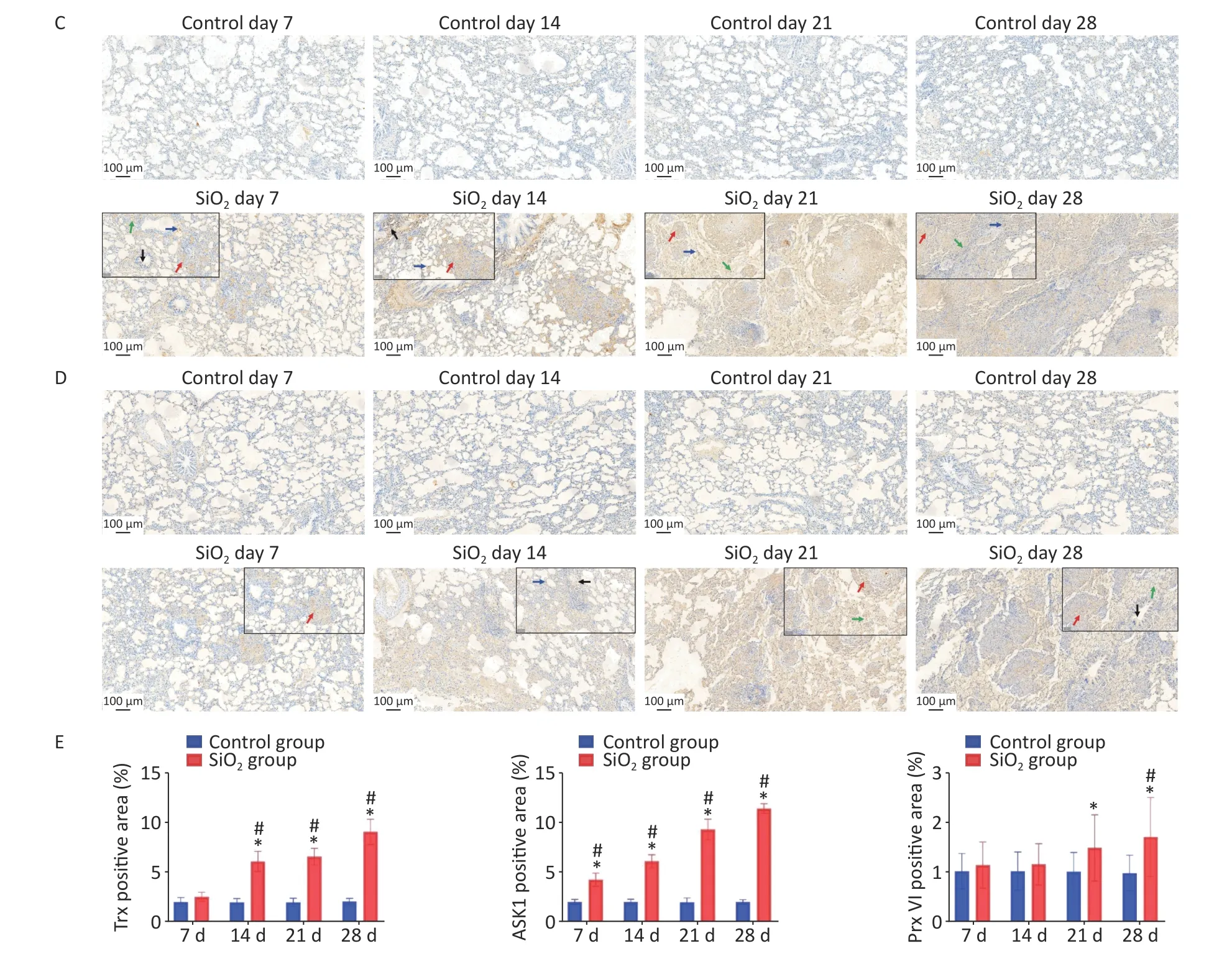

Immunohistochemical determination of protein expression in fibrotic foci was further performed to clarify the relationship between these findings and pulmonary fibrosis. The results showed that Trx expression in bronchial epithelial cells and cells within interstitial fibrotic foci on 14, 21, and 28 d was significantly higher than in control groups (P<0.01). Figure 3A, 3C shows the localization of ASK-1 in rat lungs, the expression of ASK-1 in lung tissue of rats with all-time point groups exposed to silica was significantly higher than that of the control group(P< 0.01). In comparison between silica groups, the expression of Trx and ASK-1 in lung tissue of rats in the 14, 21, and 28 d groups was significantly higher than that of the 7 d group (P< 0.05). Other than that, we intended to observe the expression association between Trx, PrxVI, and ASK-1, and with the extension of the time of exposure to silica, the expression of the three proteins significantly increased compensatory (Figure 3B–D). The Spearman rank correlation test found a significant positive correlation between the expression of Trx and ASK-1 in lung tissue induced by silica (r= 0.833,P< 0.001). A significant positive correlation between the expression of Trx and PrxVI was also observed in lung tissue induced by silica (r= 0.280,P< 0.05). In conclusion, our present results showed a possible mechanism of inflammation activation by activation of the ASK1/Trx/TrxR pathway during silica. The subsequent fibrotic effects of silica may be related to the upregulation of ASK, Trx, and TrxR expression.

Figure 3. Effect of silica on the expression of antioxidative proteins. (A) The expression of Trx, TrxR, and ASK1 protein was determined by western blotting, and the relative quantitative expression was normalized to β-actin. Bar graphs were presented as mean ± SD (n = 8). (B)–(D) Immunohistochemical staining of Trx, ASK1, and PrxVI in lung sections. Scale bar 100 μm. Inset images show a higher magnification area with positive cells. Green arrow, alveolar macrophages; black arrows, bronchial epithelial cells; blue arrows, alveolar epithelial cells; red arrows, interstitial cells, Scale bar 50 μm. (E) The mean staining intensity of the positively stained nuclei was scored by Image-Pro Plus software. Bar graphs were presented as mean ± SD (n = 4); statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P< 0.01 vs. control, #P < 0.05 vs. 7 d SiO2 group.

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

GUAN Yi conceived the design, and YAO San Qiao supervised the study. LIU Nan performed animal experiments. WANG Yong Heng, ZHAO Lin Lin, ZHOU Qiang, and CHANG Mei Yu performed the molecular biology experiments. LIU Nan and LI Gai analyzed the data. GUAN Yi wrote the manuscript. YAO San Qiao reviewed the manuscript.

#Correspondence should be addressed to YAO San Qiao, E-mail: sanqiaoyao@xxmu.edu.cn, Tel/Fax: 86-315-8805583.

Biographical note of the first author: GUAN Yi, male,born in 1987, PhD, Lecturer, majoring in Occupational lung disease research.

Received: February 11, 2022;

Accepted: May 10, 2022

Biomedical and Environmental Sciences2022年7期

Biomedical and Environmental Sciences2022年7期

- Biomedical and Environmental Sciences的其它文章

- Correction

- Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells Reverse the High Glucose Level-lnduced lnflammatory State of Macrophages*

- Oyster Protein Hydrolysate Alleviates Cadmium Toxicity by Restoring Cadmium-lnduced lntestinal Damage and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Mice via lts Abundance of Methionine, Tyrosine, and Glutamine*

- Oxidative Damage to BV2 Cells by Trichloroacetic Acid:Protective Role of Boron via the p53 Pathway*

- The putative NAD(P)H Nitroreductase, Rv3131, is the Probable Activating Enzyme for Metronidazole in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis*

- Correlation between Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep Quality in College Students