SARS-CoV-2 and the pancreas: What do we know about acute pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients?

Giuseppe Brisinda,Maria Michela Chiarello, Giuseppe Tropeano, Gaia Altieri, Caterina Puccioni, PietroFransvea, Valentina Bianchi

Abstract Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can cause pancreatic damage, both directly to the pancreas via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors (the transmembrane proteins required for SARS-CoV-2 entry,which are highly expressed by pancreatic cells) and indirectly through locoregional vasculitis and thrombosis. Despite that, there is no clear evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is an etiological agent of acute pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) positive patients often recognizes biliary or alcoholic etiology. The prevalence of acute pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients is not exactly known. However, COVID-19 positive patients with acute pancreatitis have a higher mortality and an increased risk of intensive care unit admission and necrosis compared to COVID-19 negative patients. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is the most frequent cause of death in COVID-19 positive patients and concomitant acute pancreatitis. In this article, we reported recent evidence on the correlation between COVID-19 infection and acute pancreatitis.

Key Words: Acute pancreatitis; SARS-CoV-2; Severe acute pancreatitis; Multiparametric scores; Infected necrosis; Step-up approach

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) secondary to coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) has spread rapidly from China. The disease has affected millions of people[1]. Whereas typical presentations of this infection (such as fever, cough, myalgia, fatigue and pneumonia) are well recognized, few studies reported the incidence of atypical gastrointestinal symptoms[2-5]. COVID-19 is linked to organ damage including lungs, heart and kidneys and can lead to multiple organ failure.Evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 has a strong tropism for the gastrointestinal tract[6,7]. Moreover,pancreatic injury in COVID-19 has not been common.

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory process that originates from the glandular parenchyma,causing damage and/or destruction to the acinar component first and then extending to the surrounding tissues[8-11]. There are several etiological factors contributing to its onset. However, it is possible to ascribe most of the episodes to two main causes, namely gallbladder lithiasis and alcohol abuse. Pharmacological, iatrogenic and viral causes must also be taken into account[12].

The severity of acute pancreatitis does not always correlate with pancreatic structural changes. It is possible to distinguish interstitial pancreatitis when the organ is locally or wholly increased in volume due to the presence of interstitial edema and necrotizing pancreatitis (10%-20% of all cases)[10,13,14]. It is unclear why COVID-19 starts with exclusively gastrointestinal symptoms, albeit in a low percentage of cases. However, acute pancreatic involvement induced by COVID-19 is severe and can develop rapidly. Close monitoring and admission are necessary to offer proper treatment. The following sections of this editorial discuss some of the recent findings and the approaches for a more effective clinical diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

COVID-19 AND THE PANCREAS

Viral RNA has been found in the stools of COVID-19 patients[1,2,15-17]. High replication of the virus has been documented in both the small and large intestines by electron microscopy studies on tissues derived from biopsies and/or autopsy material[7,18,19]. Additionally, fecal-oral transmission has been documented for SARS-CoV-2[20]. Some molecules are receptors for the virus. These determine a specific tropism for different tissues and organs. SARS-CoV-2 uses its surface envelope called the spike glycoprotein. By means of this protein, SARS-CoV-2 interacts and enters host cells. The virus enters the cellviathe angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. As such, the spike glycoprotein-ACE2 binding is the determinant for virus entry and propagation and for the transmissibility of COVID-19-related disease. ACE2 is expressed in human pancreatic cells and pancreatic islets and highly represented in pancreas microvasculature pericytes[6,21,22]. As ACE2 is internalized by SARS-CoV-2 binding, an imbalance of the RAS peptides can be established with a rise of angiotensin II and a decrease in angiotensin 1-7. The latter exerts anti-thrombogenic, anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving actions[23]. Laboratory abnormalities, suggesting pancreatic injury, have been noted in 8.0%-17.5% of cases in several studies[24,25], with 7.0% displaying significant pancreatic changes on computed tomography.

The etiopathogenesis of pancreatic injury in SARS-CoV-2 patients is still unclear. Both pancreatic ACE2 expression and drugs taken before the hospitalization might be involved[26]. The inflammation that occurs in the intestine causes the release of cytokines and bacteria. Both cytokines and bacteria can reach and enter the lung through the bloodstream. At this level, a direct influence on the immune response and inflammation is observed[27-29]. The gut-liver axis is also strongly influenced by damage to the intestinal mucosa and bacterial imbalance[30]. The host and the microbial metabolites present in the intestine are transferred to the liver through the mesenteric-portal circulation; these affect liver function. The liver releases bile acids and bioactive media into the biliary and systemic circulation in order to transport them to the intestine. This could lead to pancreatic function damage in patients and may also explain the abnormality of pancreatic function indicators in COVID-19 patients. It is important not to consider each COVID-19 patient with increased serum amylase level as affected by acute pancreatitis[31]. Elevated levels of pancreatic enzymes may occur during kidney failure or diarrhea in the course of COVID-19[32]. It could be useful to find some criteria that can guide clinical suspicion.

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT ACUTE PANCREATITIS IN COVID-19 POSITIVE PATIENTS?

Available literature is not able to determine whether the tissue damage leading to acute pancreatitis occurs as a result of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection or as a results of systemic multiple organ dysfunction with increased levels of amylase and lipase[33,34]. Only a few COVID-19 positive patients also have acute pancreatitis; the association between the two pathologies is infrequent. Only 10% of COVID-19 positive patients show abdominal symptoms exclusively[35]: Usually, these patients have the most severe forms of COVID-19 infections. Furthermore, it has not been demonstrated that an increased incidence of acute pancreatitis occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic period[36]. SARS-CoV-2 cannot be said to be an etiological agent of acute pancreatitis[33,37]. Acute pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients is idiopathic in most cases[37], and there is no sufficient evidence showing that COVID-19 can cause acute pancreatitis or negatively impact its prognosis.

The involvement of the pancreatic gland appears possible, in consideration of the fact that ACE2 receptors are present both on exocrine cells and on pancreatic islets[23]. In addition, the ACE2 receptor is expressed more in the pancreatic tissue than in the lungs. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 induces the onset of endotheliitis, which results in ischemic damage and that can also occur in the pancreas[38].

In the COVID PAN study, it was documented that acute pancreatitis is more severe in COVID-19 positive patients than in COVID-19 negative patients. In them, the onset of multiple organ failure can be linked to factors other than acute pancreatitis[39]. A greater severity of acute pancreatitis, an increased risk of necrosis, intensive care unit admission, persistent organ failure and the need for mechanical ventilation were observed in COVID-19 positive patients with acute pancreatitis. In this same study, 30-d overall mortality from acute pancreatitis was statistically higher in COVID-19 positive (14.7%) than in COVID-19 negative patients (2.6%,P< 0.04)[39]. Furthermore, necrosectomy was more likely to be performed in SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, occurring in 5% compared with 1.3% in the control group (P< 0.001).

The predominant organ dysfunction was respiratory failure in the majority of COVID-19 positive patients. In addition, acute pancreatitis with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 was more likely to have poorer outcomes due to double pulmonary damage[40]. Lung involvement is common in severe acute pancreatitis. This involvement can progress to full blown acute respiratory distress syndrome[40]. At present,it could be difficult to stratify the severity of symptoms and the degree of lung involvement. Acute respiratory distress syndrome due to acute pancreatitis can worsen lung injury related to COVID-19 pneumonia. Moreover, changes in the gastrointestinal flora affect the respiratory tract through the common mucosal immune system, the so-called “gut-lung axis”[27,29]. COVID-19 positive patients with gastrointestinal symptoms are more likely to be complicated with acute respiratory distress and pancreatic damage. In these patients the prognosis is poorer. In COVID-19 positive patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, attention should be paid to the patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms in the diagnosis and treatment process. It also appears essential to prevent the transmission of the virusviathe fecal-oral route. In a retrospective cohort study, Inamdaret al[37] concluded that pancreatitis should be included in the list of gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19.

There are few studies in the literature that investigate the relationship between COVID-19 infection and acute pancreatitis. In their experience, Inamdaret al[37] documented 189 cases of acute pancreatitis in 48012 hospitalized patients (0.39%). Thirty-two (17%) of these 189 patients were COVID-19 positive,with a prevalence of 0.27% of acute pancreatitis among the patients hospitalized for COVID-19.Idiopathic forms were more frequent (69%) in this patient group than in COVID-19 negative patients(21%,P< 0.0001). Wanget al[41] found that of 52 COVID-19 patients enrolled, 17% had pancreatic injury, defined as an abnormal increase of amylase and lipase serum levels. Stephenset al[31] showed that COVID-19 patients had an amylase serum peak not always related with acute pancreatitis. They enrolled 234 patients, 158 of which had a serum amylase level three times greater than the normal upper limit, but only 1.7% of the studied population met the revised criteria of Atlanta for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis[31].

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography 10 d after the onset of acute pancreatitis. A: Necrotic collection, with a noticeable wall, dislocating stomach; B: Necrotic collection occupying the majority of pancreatic head and compressing the duodenum; C: Multiple collections of fluid and necrosis involving the cephalad portion of the pancreas, multiple peripancreatic collections around the spleen and the left paracolic gutter.

COVID-19 VACCINE AND PANCREATITIS

Vaccines are considered one of the most important public health achievements of the last century. Many vaccines have side effects. One of these adverse events is the onset of pancreatitis. In these cases, it is believed that acute pancreatitis is secondary to an immunologically induced phenomenon as demonstrated by reports in the literature after the administration of vaccines against the hepatitis virus or other viruses[42-44]. The vaccine BNT162b1 developed by Pfizer-BioNTech is a nucleoside-modified mRNA that encodes the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The vaccine RNA is formulated in lipid nanoparticles for an efficient delivery into cells after injections[45].

In the literature there are several cases reporting acute pancreatitis after mRNA-based vaccine[46-50].Although the vaccine has been proven to be effective and safe, vaccine-induced side effects have been observed. There are nausea, diarrhea, decreased appetite, abdominal pain, vomiting, heartburn and constipation among the most frequently reported gastrointestinal side effects. Most of the cases describe mild acute pancreatitis, however Ozakaet al[46] and Walteret al[47] reported a single case of necrotizing pancreatitis. According to Pfizer’s data, 1 case of pancreatitis and 1 case of obstructive pancreatitis as adverse reactions were observed during the phase II/clinical trial of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The trial included about 38000 participants, indicating that such a link between vaccination and pancreatitis is a very rare adverse event[51]. Between December 9, 2020 and July 21, 2021, information obtained from the United Kingdom database showed 275820 adverse reaction reports, which included 18 cases of mild acute pancreatitis and 1 case of necrotizing pancreatitis[52]. In France, out of a total of 42523573 doses,the Agence Nationale de Securité du Medicament et des Produits de Santé reported 57 cases of acute pancreatitis[53]. VigiBase, the World Health Organization global database of individual case safety reports, included 298 cases of acute pancreatitis and 17 cases of necrotizing pancreatitis[54]. The Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco reported 497 gastrointestinal adverse events equal to 14.1% of the total observations in 1 year. The document does not specify the number of cases of acute pancreatitis[55].Although it is difficult to make conclusions about the likelihood of the vaccine being the etiologic factor of pancreatitis, it is essential to continue monitoring it for possible under-reported side effects until we have extensive long-term data available in post-marketing surveillance for long-term and rare side effects. Surveillance is also necessary because there are currently no conclusive data on the severity of pancreatitis in the population of subjects vaccinated against COVID-19 compared to patients who have not undergone vaccination. Preliminary results would document a reduced incidence of severe forms of acute pancreatitis in subjects vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2.

DO WE NEED TO CHANGE THE DIAGNOSTIC AND THERAPEUTIC APPROACH?

Since pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients occurs more frequently in severe forms, treatment must be intensive and prompt. It is crucial to define and stratify the severity of illness in patients with acute pancreatitis because of the extreme range of potential clinical courses due to the wide range of organs and tissues that may become involved. It is also fundamental to identify patients with potentially severe pancreatitis who require a multidisciplinary approach and an earlier and more aggressive treatment[56,57]. Suspected acute pancreatitis can be confirmed with laboratory and instrumental investigations.Increased pancreatic enzymes levels are associated with a poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients. Recent findings show that the increment of pancreatic enzymes are significant in critical COVID-19 patients,but only a few of them progress to acute pancreatitis[58]. The rapid response of C-reactive protein to changes in the inflammatory process intensity has also suggested its use in the management and monitoring of acute pancreatitis. C-reactive protein is not specific, and although it is correlated with severity, it cannot be used to predict clinical evolution. Serum procalcitonin is also one of the parameters used in predicting the development of severe acute pancreatitis. Its continuous increase correlates with a bacterial superinfection of pancreatic necrosis[59]. In all patients with or without SARS-CoV-2 illness contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan is the gold standard for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis to evaluate both pancreatic and extrapancreatic alterations (Figure 1).

Figure 2 Abdominal computed tomography 6 mo after the onset of acute pancreatitis. A and B: The double pigtail stents positioned during the endoscopic necrosectomy through the stomach is highlighted. Endoscopic necrosectomy through the stomach was performed 4 mo prior; C: A necrotic collection is evident in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen.

Figure 3 Abdominal computed tomography scan documenting correct placement of lumen-apposing metal stents for the treatment of walled-off necrosis in coronavirus disease 2019 positive patient. A: Sagittal scan; B: Front scan.

The revised Atlanta classification provides a good clinical distinction between mild, moderate and severe acute pancreatitis, and it is used in most COVID-19 positive patients with acute pancreatitis[8].Several scoring systems have been developed to predict the severity of acute pancreatitis; however,none of them represents a gold standard. The scoring systems are without clinical relevance because of their low predictive value[56]. The bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis failed to identify the severity of acute pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients[37].

Early fluid resuscitation is recommended in order to improve tissue perfusion[60], and the maintenance of microcirculation may be associated with resolution of multiple organ failure[61],especially in patients with COVID-19 and acute pancreatitis. Enteral nutrition is safe during acute pancreatitis[62]. Moreover, supplementation of enteral nutrition with probiotics may decrease septic complications. In patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation, early enteral nutrition is associated with earlier liberation from ventilator support, shorter intensive care unit and hospital stay and decreased cost[63,64].

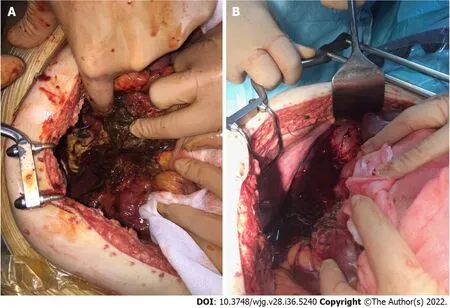

Figure 4 Intraoperative photos. A: Surgery was performed for severe abdominal hypertension due to acute pancreatitis with necrotic collections in the retroduodenal region; B: Surgery was performed for severe abdominal hypertension due to acute pancreatitis with necrotic collections along the paracolic gutter.

Most patients with sterile necrosis can be managed without invasive treatments. Walled off necrotic collections or pseudocysts may cause mechanical obstruction and a step-up approach is indicated.Percutaneous or transmural endoscopic drainage are both appropriate first-line approaches in managing these patients (Figure 2). However, endoscopic drainage is preferred as it avoids the risk of forming a pancreatocutaneous fistula. In the earlier phase of the pandemic, patients with COVID-19,especially with severe pneumonia and considered highly contagious, did not undergo endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic treatments. In the later stages, patients with COVID-19 and acute pancreatitis were subjected, with necessary precautions, to percutaneous and endoscopic treatments similar to the COVID-19 negative patients (Figure 3).

The step-up approach might reduce the rates of complications and death by minimizing surgical trauma in already critically ill patients[65,66]. Currently, there is general agreement that surgery in severe acute pancreatitis should be performed as late as possible[67]. In the management of necrotizing acute pancreatitis, open operative debridement (Figure 4) maintains a role in cases not amenable to less invasive endoscopic and/or laparoscopic procedures. Open operative debridement was performed in patients with COVID-19 related lung symptoms and lesions.

CONCLUSION

In pandemic times, clinical conditions could be worsened by COVID-19 infection. SARS-CoV-2 cannot be said to be an etiological agent of acute pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis in COVID-19 positive patients is idiopathic in most cases, and there is no sufficient evidence showing that SARS-CoV-2 can negatively impact prognosis. On the other hand, acute pancreatitis with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 is more likely to have worse outcomes due to double lung damage and greater pancreatic severity. The multiparametric scores could not recognize and stratify the severity of pancreatic diseases and concomitant COVID-19 infection. In these patients, computed tomography is the gold standard for the diagnosis. Management of COVID-19 positive patients with pancreatitis is complex, and it is optimally provided by a multidisciplinary team. Operative treatments should be modulated, preferably, from the least to the most invasive option. Thus, surgical necrosectomy is relegated to the role of “l(fā)ast resort”, remembering that necrotizing pancreatitis is a heterogeneous disease with marked variations in extent and course.This also means that one size treatment does not fit all.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Brisinda G and Chiarello MM equally contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and must both be considered first author; Chiarello MM and Brisinda G conceived the original idea; Tropeano G, Alteri G,Puccioni C, Fransvea P and Bianchi V performed a comprehensive review of all available literature and summarized the data; Brisinda G and Chiarello MM meet the criteria for authorship established by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and verify the validity of the results reported; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Italy

ORCID number:Giuseppe Brisinda 0000-0001-8820-9471; Maria Michela Chiarello 0000-0003-3455-0062; Giuseppe Tropeano 0000-0001-9006-5040; Gaia Altieri 0000-0002-0324-2430; Caterina Puccioni 0000-0001-6092-7957; Pietro Fransvea 0000-0003-4969-3373; Valentina Bianchi 0000-0002-8817-3760.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年36期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年36期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: Beyond the boundaries of the liver

- Impact of sarcopenia on tumor response and survival outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by trans-arterial (chemo)-embolization

- Early extrahepatic recurrence as a pivotal factor for survival after hepatocellular carcinoma resection: A 15-year observational study

- Esophageal magnetic compression anastomosis in dogs

- Liver-specific drug delivery platforms: Applications for the treatment of alcohol-associated liver disease

- P2X7 receptor as the regulator of T-cell function in intestinal barrier disruption