Deconstructive Analysis of New Media Communication from Translanguaging Perspective

Chen Weimin

School of Foreign Languages, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, China

Email: cwmaken@163.com

Zeng Jingting

School of Foreign Languages, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, China

Email: jtzeng@just.edu.cn

[Abstract] New media places language in platforms for knowledge sharing, shaping it into various forms and changing ways of transmission. This paper deconstructs dichotomy of short and long videos from translanguaging perspective. Platforms involved belong to translanguaging space where users send comments to show attitudes and share experiences, while in bilingual interaction superiority of language is psychologically reduced, all requiring users’visual and auditory sensors to handle linguistic symbols in unearthing deeper meanings. Language inside is found pictorial, softened and simplified, trending to positively step backward.

[Keywords] Deconstructive Analysis; New Media; Communication; Translanguaging

Introduction

Back in the late period of the 1960s, Jacques Derrida challenged the traditional belief of structuralist theories, aiming to overthrow the Western cultures and traditions represented by those who established binary opposition like male and female, with the former ruling the latter. However, from criticizing linguistic structuralism of Saussure to Western metaphysics in philosophy, Derrida was not to reverse the dichotomous situation, but what he recommended actually was“pluralism”(Zhu, 2006, p. 303). With the popularity of new media communication, Derrida’s deconstructivism can still finds its role in the 21st century. It remains a mystery in the fate of traditional communication in terms of the way of chatting, video watching and message sending. In addition, new media communication is not only conducted with one language, but also engages in two or more than two languages, so the notion of translanguaging can help a lot in such phenomenon.

“Translanguaging” (Baker, 2010, p. 288) came from a Welsh word“Trawsieithu”firstly used by Cen Williams (1996), which describes the employment of two different languages like teaching in Welsh and reading or listening in English in pedagogy. And“trans”according to Li (2018) has contained aspects as: Its practical values are more than those of different currently constructed meaning-producing systems, and it brings revolution in language, cognition and social frameworks. More importantly, the meaning of‘trans’narrows the gap between isolated disciplines like linguistics and education, redefining the concept of language, its acquisition and application. In today’s technologydriven society, the idea of ‘trans’ has refreshed the essence of language, for which language is not merely written, but also visual as well as auditory. Now with translanguaging, García (2009) mentions that it serves a better tool for bilinguals to have an insightful view of the bilingual world they are living in, which also makes it possible to develop meaning and transmit message.

Translanguaging, with the increasingly globalized background, its possibility of seeing one language in another language is increasing. Under the impact of current technological tide it can reveal its appealing in the co-existence of two different official languages or language varieties. Therefore, this article plans to find out what linguistic features are in new media communication in terms of chatting, video watching and message sending which are detailed as dichotomies of short and long video, fragmented English and pure Chinese, then analyzing them by qualitative methods from the perspective of translanguaging.

Short and Long Videos

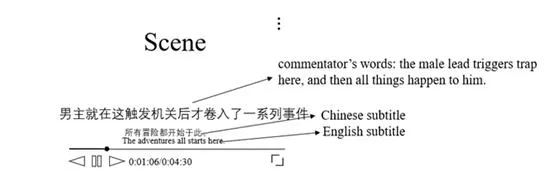

Short video refers to clipped video that is issued by uploaders of video websites to introduce plots and make commentaries of English movies or soap operas. Normally, its time is less than 5 minutes, and it is usually clipped from long video with the time length more than one hour. In the Figure 1, short video contains Chinese lines of a commentator, the Chinese and English lines of the original movie, in which the commentating Chinese lines are both the plots of the movie and illustration of the commentator. As a result, viewers of this short video have to read Chinese and English subtitles, watch movie scenes and listen to louder Chinese speaking but relatively lighter English voices of the movie characters. So viewers’involvement in the video is rather complex and multifunctional, which deals with linguistic transition as well as visual and auditory cooperation.

Figure 1 Commentary of Clipped Short Video

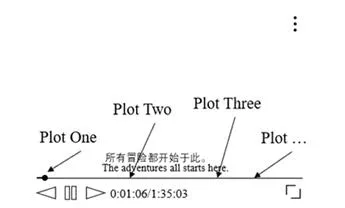

Figure 2 Long Video Combined by Complete Plots

During such process, viewers’attention is attracted to great extent so they can easily remember something they are interested in from the movie. Here “commentator to viewers” guidance resembles the mode of teacher to student, in which the commentator as if a teacher is leading his listeners to the outline of the movie and its core part. In this mode, the traditional way of face-to-face communication or instruction is completely changed, because through the clipped video the commentator uses motional scenes trying to get the viewers involved into the movie and let them know his thinking of it which is combined with his personal experience. Like students, viewers are also passive to accepted new experience from both the short video and the commentator’s utterance, which makes the acquisition of knowledge becomes easier because what they have to do is to click the video and then finish it. But the entire process is spontaneous. For one thing, maker of the clipped video though spending much time and energy perhaps for profitable purposes, he is unconsciously conveying information or even new knowledge; for another, viewers naturally click the video taking in certain foreign cultures or traditions unknowingly.

As for the long original movie (Figure 2), viewers have to deal with Chinese and English subtitles and English voices of characters, which would be a choice for English learners to improve their speaking skills. However, the first sight of the long time-length of the video would undermine viewers’confidence to watch the movie to the end, and the long-lasted plot would distract people’s attention, making them prone to neglect details. More importantly, long video has no commentator so that viewers have more freedom to digest what they have watched by themselves, but the focus of this digestion is mainly about sorting out the developing line in the movie rather than considering story construction or analysis. From conventional standpoint, long video can offer audience a complete understanding of the story line, and without others’comments audience can bring their mind into full play exploring the underlying significance of the movie. However, with the proliferation of Internet, information becomes pervasive and knowledge sharing becomes a normal state. Therefore, the clipped short video can meet people’s needs of both enjoying the enchant of stories and investigating the essentials behind the scene. Sharing is the spirit of short video, because the commentator is sharing his arguments with the viewers as the latter are watching the video, and typically there are two possibilities: the one is sympathetic, and the other is opposite, which can provide the viewers to think about some phenomenon with another perspective, finally reaching the communicative goal of sharing knowledge.

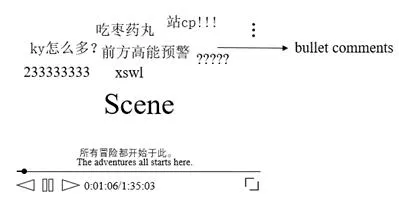

Figure 3 Bullet Comments

Another form of new media communication should be mentioned, which is bullet comments (Figure 3) flying on the scenes when the video is played. Bullet comments are visual, well-arranged viewpoints made by audience, and an interactive communication among viewers themselves perhaps even in different kinds of languages. For the figure, meanings of those expressions can be understood as following:

站cp: to support a romantic relationship, in which ‘cp’ is shortened from the word ‘coupling’.

吃棗藥丸: to be doomed sooner or later, which comes from the same sound of the Chinese ‘遲早要完’.

ky怎么多: why are there so many people saying inappropriate words, in which ‘ky’ is taken from the Japanese ‘空気が読めない’ (kuuki ga yomeinai).

xswl: to laugh out loud, in which ‘xswl’ is the initial sounds of the Chinese Pinyin in words ‘笑死我了’ (xiao si wo le).

Mixed languages are employed in bullet screen, which makes it easier to share information from different cultural background. And with the coordination among movie scenes, i.e. English and Chinese subtitles and flying comments, viewers not only deal with various linguistic forms, but at the same time absorb others’comments and then make their own comments. With bullet comments in video, real-time communication on a large scale becomes possible, and information and knowledge are accessible than ever before. As a result, the bullet comment has become an important factor in the deconstruction of the relationship between short and long video, in which long video has always taken up much room in entertainment and information exchanges. However, with new media technologies, short video has increasingly turned to be people’s another choice to deliver and receive message, and it symbolizes an easy channel for video makers to display what they want to advocate to their audience, and a time-saving window for viewers to acquire information, which turns out that short video would outweigh long video. It is also should be noticed that since bullet comments can both be applied to short and long video, it is reasonable that longer the movie is, more bullet comments it will have. Therefore, it can only be acknowledged that video watching in nowadays has become another major way to exchange information so that the form of information as well as co-existence of different languages need to be paid more attention.

Translanguaging Perspective

With new media technologies, communication in commentaries of short video, bullet comments and fragmented English, is conducted with the involvement of several official languages and language varieties, which can bring out the function of translanguaging. The bullet comments discussed before are practices through using Mandarin, Japanese and English, still conducted without barriers, which features translanguaging as‘fluidity’,‘hybridity’, ‘locality’and‘globality’(Otsuji & Pennycook, 2010, p. 252). In today’s global background, most people are capable of speaking at least two languages which means that communication of translanguaging is happening all the time. As a result, the extensive translanguaging space (Li, 2018) can be established, in which Chinglish phrases like ‘good good study day day up’is universally accepted in many regions making language strangeness decrease. Here platforms of new media communication can be regarded as a translanguaging space, in which experience exchangers and bullet comment makers are practicing translanguaging, they communicate regardless of the social space formerly created by different practices in different places, and during their communication they share experiences and attitudes into meaningful behaviors making the translanguaging space extend and then develop new values and new practices (Li, 2011).

In addition, new media communication does reflect viewpoints of many scholars of translanguaging studies who insist that languages are multi-semiotic, multimodal and multisensory. Cook (1992) has investigated the holistic multicompetence in human mind, and Li (2018) believes that in communication people use many ways like written or visual materials to produce and comprehend information. Therefore, in new media communication, emojis are fully used with facial expression together with official languages and language varieties, in which static signs are reconstructed in people’s mind so that they and the attached words give out dynamic impact shaping certain image with meanings. As for commentaries in short video, different languages are coordinated in visual scenes and auditory subtitles, while in bullet comments languages are put in motion. Above all, languages in new media communication have coordinated people’s sensors to grasp points of various information, which obviously suggests that the phenomenon of translanguaging has to deal with information processing through cognitive, auditory, articulatory and visual abilities. For new media communication, languages are not only in the form of words or written texts, but also in the form of a more active style in which languages are transformative requiring people’s holistic ability of mind and sensory operation to precisely figure out their real meanings.

Discussion and Conclusion

Under the guidance of translanguaging, the linguistic features in new media communication can be figured out. The first feature is pictorial language, in which message conveyers use pictures or clipped films to attract people’s attention, sending out whatever they consider meaningful. In new media communication, more pictures are used including motional and motionless ones, above which facial expressions, the carrier of information, minify chances of embarrassment but narrow down the sense of alienation. Emojis, for example the typical representation of pictorial language, are combinations of looks and languages, from which minute psychological performance can be observed with cooperation of the emoji receivers’brain and sensor, despite the actual spatial or temporal distance. For the long time, language is either written or heard but the language system is dynamic and it can evolve itself into new forms with new meaning. As for pictorial language, its users make language signs dimensional and use language image to construct their personal experiences in order to communicate more effectively. Secondly, in new media communication language is softened or we can say its restrictions are less rigorous, because correct rules of using language are violated and languages of different countries are frequently matched together. On the one hand, vocabulary of one language is often borrowed in spite of grammar in informal communication of new media. For example,‘wall eye knee’is the mere combination of three totally unrelated words in English, but because of their pronunciations the phrase is used as ‘我愛你 (wo ai ni)’ in Chinese which means ‘I love you’. On the other hand, the combined form of Chinese and English is called ‘New Chinglish’ (Li, 2016) which means English expressions are reorganized with completely different meanings used in communication by Chinese speakers of English, like

“duck不必”, i.e. “大可不必” (da ke bu bi) meaning there is no need to do something.

Thirdly, language in new media communication becomes simplified in that language is shortened and its abbreviation is occasionally used. It is because in new media communication the main objective is to obtain information within the shortest time, and although the form of language is everchanging, the complete meanings of these contracted words are still predominant. Moreover, another view should be pointed out that at present language has the trend to step backward, but the movement is positive. The appearance of new media makes communication tend to apply pictures in language, rendering pictures to have the function of constructing meaning which seems to dwarf the position of language. Under such background, the major factor of language which should concern its meaning is still pursued but its signs or symbols are rampantly invented making language tend to be pictographic. And language is informal in new media communication where words and phrases are cut off for less linguistic effort, grammar is breached for concise communication, and sounds are largely retained for less phonetic effort but with relatively complete meaning. However, with all these linguistic changes in new media communication, though language regresses, it effects smooth communication, creates humor and makes sure people to gain enough information in available time.

Proceedings of Northeast Asia International Symposium on Linguistics,Literature and Teaching2022年0期

Proceedings of Northeast Asia International Symposium on Linguistics,Literature and Teaching2022年0期

- Proceedings of Northeast Asia International Symposium on Linguistics,Literature and Teaching的其它文章

- A Comparative Study of the Phonology and Phonetics of Chinese and German Vowels

- Exploration to the Application of In-person + On-line Blending Teaching Method to College English Teaching in Translation Based on Group Discussion

- A Probing into What Extent Listening Comprehension Ability Influences on Chinese English Learners

- Exploring Linguistic Landscape of the Qianzhou Ancient Town in Xiangxi through Ecological Linguistics

- Teaching Practice and Research of Scientific and Technical French Translation Based on Production-Oriented Approach

- A NEW“5W+1”COMMUNICATION MODEL TO TRANSLATE CHINESE KEYWORDS TO ENHANCE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNICATION