An Empirical Assessment and Analysis of the United Nations Convention on Contracts Judicial Applicability in China

Chen Sihan*

Tsinghua University

Abstract: Chinese domestic legislation on the judicial applicability of international treaties has been unsettled,especially under the Civil Code, which is silent on this issue.However, previous studies have depicted an image of a “pro-CISG” attitude in Chinese legal practice, which is distinguished from the tendency to circumvent the CISG in other jurisdictions such as the U.S.This contradictory phenomenon,namely the absence of guiding norms versus the embracement of the CISG in judicial practice, is rarely discussed, especially within the context of civil codification and recent external economic challenges.To verify this paradox, a manually collected dataset of 223 court decisions from 2013 to 2023 identifies some basic characteristics of the CISG judicial applicability in China, including the application rate, legal reasoning paths, citation frequencies of specific provisions, and some qualitative observations about the judicial behaviors in the international sales dispute resolution.The main finding is that Chinese courts have been applying the CISG at an obviously higher rate,compared with both their foreign counterparts and the general rate of applying foreign law in the international civil and commercial litigations in China.To explain this gap between “l(fā)aw in book” and“l(fā)aw in action,” the context of Chinese judicial practice should be considered.Despite the vagueness of domestic legislation, the judicial policy promotion, the innovative guiding cases system, the legal transplantation, and other factors may contribute to the “pro-CISG” attitude.As for the future promotion of CISG in the Chinese style of international commercial dispute resolution, these factors may coordinate with the legislative improvements.

Keywords: CISG; China; Judicial Applicability; Empirical Study

Established as a milestone of uniform substantive law in the 20th century,the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods(CISG) has had an unparalleled influence on both transnational trade and domestic business (Schwenzer & Hachem,2009, p.457).By the end of 2023, the CISG has been ratified by 95 parties, including the major players in international trade, such as the U.S., China, and Germany.Given the rising trend of unilateralism in contemporary international affairs, the success of the CISG unification is a precious example to reflect on empirically (Schroeter, 2014, p.649).With this concern, scholars from different jurisdictions have already shed light on not only the “l(fā)aw in book” but also the “l(fā)aw in action” (Pound, 1910, p.12), namely the practice of the CISG.The empirical studies of the CISG in practice generally include two perspectives: the assessment (how is CISG practiced) and the analysis (why is it so).

From the assessment perspective, recent comparative empirical studies show that the attitudes toward the CISG may vary in different jurisdictions.China has been depicted as a jurisdiction where lawyers are in favor of CISG.Such a “pro-CISG” attitude means that Chinese lawyers tend to apply CISG, not to opt it out (Fitzgerald, 2008, p.3; Koehler & Guo, 2008, p.45; Moser, 2015,p.19).This opinion is largely based on an observation of the transactional lawyers in both China and the U.S.(Coyle, 2016, p.195), as well as a recent survey conducted among German lawyers(Lehnert & Sch?fer, 2021, p.146).However, the litigation aspect is absent from this picture.And when it comes to civil-law jurisdictions, the tradition ofex officio, namely the active duty of judges, has not been fully considered.In other words, theex postsupportive attitude for judicial applicability may be the prerequisite condition ofex antelawyer choice of CISG.Ignoring the judicial applicability of CISG is improper when claiming the predominance of the “pro-CISG”attitude in China.

As for the analysis of the difference, researchers have listed a series of possible factors which may influence the behavior of applying the CISG.For transactional lawyers, the legal education,knowledge dissemination, and economic reasons may be of significance (Lisa, 2010, p.417;Moser, 2017, p.250).For dispute resolutions, the “judicial behavior theory” provides an insight that norms, attitudes, and strategies are potential factors that contribute to judges’ decisions (Perino,2006, p.497).The “strategy model” has gained popularity as it returns judicial behaviors to a political context, in which judges are incentivized and constrained by institutional designs, like performance rewarding, accountability, and the interaction with other power branches (Epstein& Jacobi, 2010, p.341).This insight has not been applied to the comprehension of the CISG applicability in Chinese litigations.

Therefore, this article will adopt a two-step structure.The first step is to empirically examine the judicial applicability of the CISG in China during the past decade, which includes: (1) the CISG judicial application in Chinese courts; (2) the legal grounds and reasonings for these applications;(3) some empirical features of the CISG-related cases in China.The second step is a theoretical comment, which embeds the application of the CISG into the context of Chinese legislation and adjudication.The institution of “political and legal framework,” the policy of economic openingup, the guidance cases system among other mobilizing policies, and the belief of the CISG as an“authority source” will be discussed as possible explanations.As a policy implication, these factors may be taken into consideration for the future renovation of other uniform rules.

The design and methodology of this article benefit from a recent study on the application of CISG in the U.S.Courts from 1988 to 2020 (Arlota & McCall, 2023, p.541).Due to difficulty in data collection, this article cannot cover the same length of time.However, with different questions and data, this article still provides an empirically distinct response and prepares for further crossjurisdiction comparisons.Another important literature for this article is the ground-breaking and comprehensive work to examine the Chinese court decisions on the CISG applicability (Liu, 2017,p.873).Following its basic framework, this article contributes an updated dataset, which illustrates the stability of the Chinese pro-CISG attitude under the US-China trade conflict, the pandemic shock, regional wars, and other global challenges since 2016.Besides, this article goes further by comparing with other jurisdictions, making extra comments, and identifying the ignored“borrowing CISG as an argument” behavior, which depicts a more comprehensive picture of the CISG in Chinese judicial practice.

The Empirical Study

This section introduces the methodology employed and illustrates the main findings derived from the collected data.The descriptive reports include the general characteristics of disputes, the application rate of the CISG, the legal reasoning of the choice of applicable law, the role of choiceof-law clause, and finally, the frequency of references to specific CISG articles.

Methodology

Courts do not disclose all the decisions, and the publishing rate of judicial decisions is not stable among districts and years (Liebman et al., 2022, p.177).The published cases do reflect a general picture of Chinese judicial practice, but not necessarily in a statistically accurate way.Therefore, to avoid any misleading or distorted representation, this article focuses on statistical description and qualitative analysis, without involving any causal-inference methods like linear regression.

The data were manually collected from China Judgments Online (an official website for judicial decision publication), Chinalawinfo (a private database similar to Westlaw or Lexis in the U.S.), China International Commercial Court Database, and Foreign Law Ascertainment(a database recently established by Guangzhou Intermediate People’s Court).The keyword for search is “Contract of International Sale of Goods,” with the category of the case being “civil and commercial disputes.” The period of search ranges from January 2013 to December 2022(identified with the date of decision).The reasons for selecting this period: (1) the Belt and Road Initiative of China started in 2013; (2) In 2013, the Supreme People’s Court issued theInterim Measures of the Supreme People’s Court on the Publication of Judgments by the People’s Courts on Line, promoting the openness of decisions; (3) 2013 marked the enforcement of theInterpretations of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning Application of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Choice of Law for Foreign-Related Civil Relationships(I),which specifies the rules of conflict law.

Despite continuous reforming, the Chinese judicial system has a two-instance-at-four-level hierarchy, which means a dispute may be decided and then reviewed at most three times.To avoid repetitive counting, when there are multiple decisions available in the litigation course of a single case, this article only identifies the first decision, unless the later decisions are about the applicable law or the upper court makes a concurring reasoning over the CISG applicability.Another point is that the court decisions over substantive issues (judgment) or procedural issues (ruling) are different in form and effect.The following discussion only includes judgments.Besides, several incomplete cases (issued by some lower-level courts as typical cases in white reports or covered by media, without the full text) are excluded.

The outcome includes 223 results.This result does not include those false-positive cases,which make only verbal references to CISG but are in essence irrelevant to the international sale of goods (but these cases will also be discussed in the following comments).

Basic Descriptions

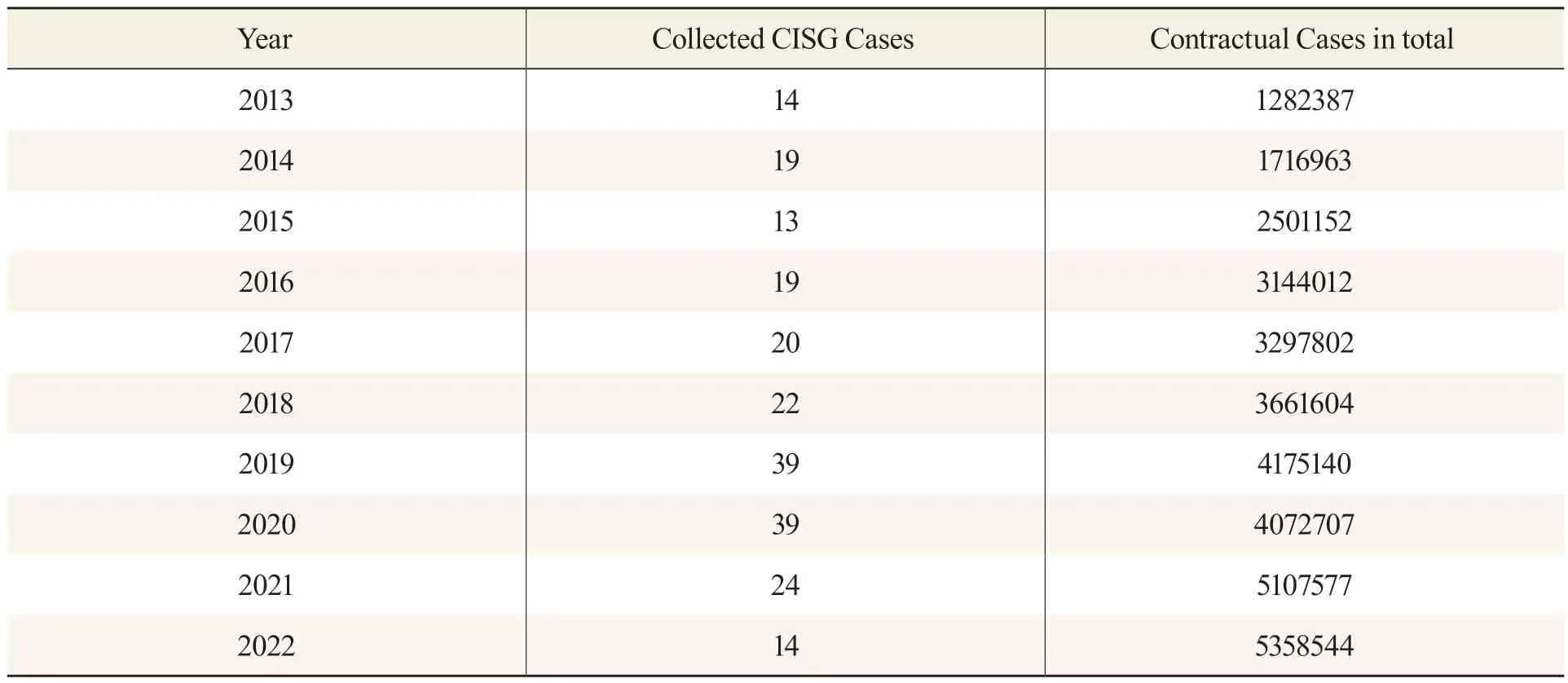

The volume of decisions from 2013 to 2023 remains relatively stable.Table 1 lists the collected decisions, with the civil cases in total as a background.The civil contractual cases data can be accessed through the annual public reports of the Supreme People’s Court (first instance,judgments only).

Table 1 The Collected Decisions from 2013 to 2023

The contractual cases in total serve both as a statistical test for the reliability of this collected sample.For this goal, without reasonable explanation, such as an urgent shift in law, judicial policy, or the economic environment, the rate of CISG cases against the contractual cases in total is supposed to fluctuate around a stable level.Such a proportionality has been observed in previous studies (Slakoper, 2019, p.170).This sample roughly fulfills this requirement since the number of CISG cases generally rises along with the cases in total.But it is important to notice that the online publishing of judicial decisions, as a judicial reform measure, has been slowed down due to privacy protection concerns and other public policies, which explains the dropping in cases in 2021 and 2022.

As for the spatial distribution, the provinces with the largest number of the CISG cases are the maritime ones.Zhejiang (69), Guangdong (52), Shandong (31), Shanghai (24), Jiangsu (17), and Fujian (13) are the provinces that contribute the majority of the disclosed CISG cases.This may correlate with their coastal geography and export-oriented industry, in which the international sale of goods plays an important role.As for the parties, in the collected data, most cases involve a party whose place of business is located in China.The majority of the other party’s business places are in developed countries, with the United States (42), South Korea (35), Singapore (18),Germany (14), Italy (11) Canada (10), having more than ten 10 cases each.This may not accurately reflect a real trade structure since the wide application of English law and arbitration may diverge the disputes and reduce the observed frequency of the UK and India.Besides, it is surprising to see that Japan (5) has a significantly lower number of cases compared to South Korea, the reason of which remains unclear.

Goods are diversified.Previous small-scale studies pointed out that Chinese solar companies embrace the CISG, which “indicates that the perceived utility of that treaty in transactional planning can vary by nationality and industry” (Coyle, 2016, p.231).The rising bargaining power of Chinese business “could ultimately serve to slowly force CISG exposure on more reluctant jurisdictions such as the U.S., Canada, and Australia.” (Spagnolo, 2010, p.37).This article finds, from a judicial perspective, that the basic business relationship is not limited to the solar industry or other fields where Chinese players enjoy a rather powerful technological status.In fact, the past decade has witnessed a wide practice of the CISG in dispute resolution for both the first and second industries, ranging from agriculture and aquaculture to manufacturing.In these trades, Chinese players are usually in the position of seller/exporter (157 cases) and less frequently as buyer/importer (62 cases), with the remaining cases involving two foreign parties or an intermediary trade.Export covers almost every manufacturing sector, both consumer products and industrial products.For import, machines and mechanical parts, seafood, and agricultural products, solid waste (banned since 2021) are the most frequent goods.

The application of the CISG and the legal reasoning

This article summarizes and reports the judicial application of the CISG as follows.Unlike the previous research (Liu, 2021, p.886) is that this article does not set the first-step standard as“resorting to Art.1(1)(a),” but “analyzing the applicability of CISG” in general.In this way, the legal reasoning path can be illustrated.

The collected sample consists of 223 cases.Ten cases are absent from this table due to the ambiguity of the decision.For example, the “false advertising” (further discussed at the end of this section) appears to be a CISG-applicable case based on textual analysis, but the norms from CISG are not really applied to evaluate any legal relationship in the case.Another scenario is that the judge “sits on a fence” by arguing that Chinese domestic law provides the same rule as CISG,so it is not an issue to decide the applicable law.These cases do not fall into any categories in the table above.

For this table, three notes should be made.First, to test with Art.1(1)(a) of the CISG test does not mean a textual citation of Art.1(1)(a).As long as the judge identifies the sale of goods contract and mentions an internationality test (the contract is between parties whose places of business are in different Contracting States), this article treats it as a CISG-based application.Second, the“judicial application rate” cannot directly be matched with the “opt-in rate” in previous studies,since the application of CISG is not necessarily a correct decision.For example, there are cases involving Malaysia,①Civil Judgment (2011) X MC No.575the United Arab Emirates,②Civil Judgment (2013) YF M3Z No.39the United Kingdom,③Civil Judgment (2012) ZHSW MC No.164the Philippines,④Civil Judgment (2012) ZJSW MC No.14India,⑤Civil Judgment (2016) Z 01 MZ No.5212and Tanzania,⑥Civil Judgment (2019) Y 0391 MC No.952in which CISG shall not apply (except the choice of CISG under party autonomy).

Despite these notes, a pro-CISG attitude can still be inferred from the judicial application rate (83.4%, 186 cases in 223 cases, as indicated in Table 2 above).Though not a precise or fullsample study, this rate can be safely interpreted as high, especially when compared with the 59.5% of CISG application in the counterpart courts of the United States (Arlota & McCall, 2023,p.570).Besides, a recent empirical survey indicates that 98.10% (15455 in 15755 cases) of the international contract disputes in Chinese courts are finally decided pursuant to domestic (Chinese)law (Tsang, 2021, p.360).Against this background, it is safe to verify the “pro-CISG” attitude as a unique feature in Chinese litigation.At least, Chinese courts are more open to CISG than the law of other foreign states.As mentioned at the beginning, party autonomy has been emphasized by previous studies.However, in the collected cases, the contractual agreements on applicable law are rare.Only 12 cases in the 223-case sample involve parties’ autonomy to choose an applicable law in the contract, with the law of the United States, China, and Germany chosen.Besides, in one case, the parties agreed during the litigation to exclude CISG.①Civil Judgment (2013) SZF MZ No.91The applicable law of other cases is not agreed through the contractex ante, but decided by the court.This observation does not necessarily contradict the previous idea about the “l(fā)ow opt-out rate” in China, since a contract negotiated by lawyers will probably also have a dispute resolution term referring to other dispute resolution paths, which may create a biased observation with a litigation dataset.

Table 2 The Application of the CISG and the Test Paths

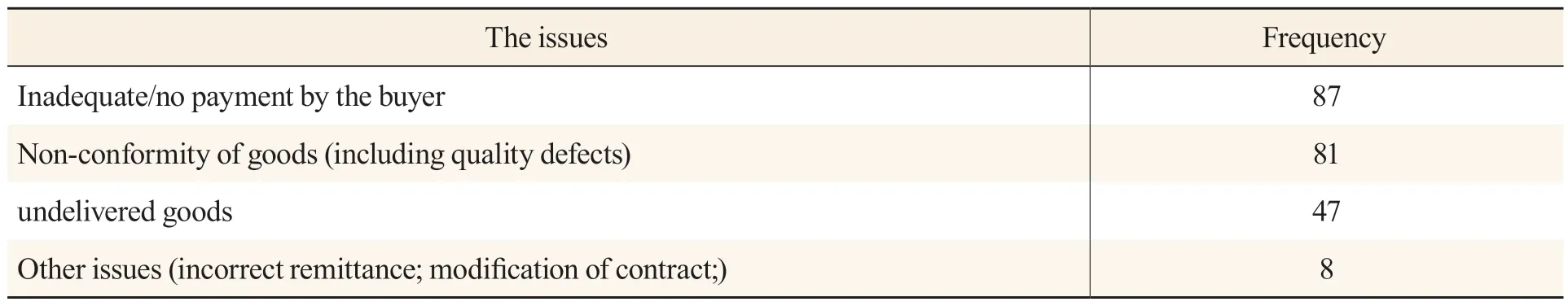

Table 3 The Frequency of Issues Involved

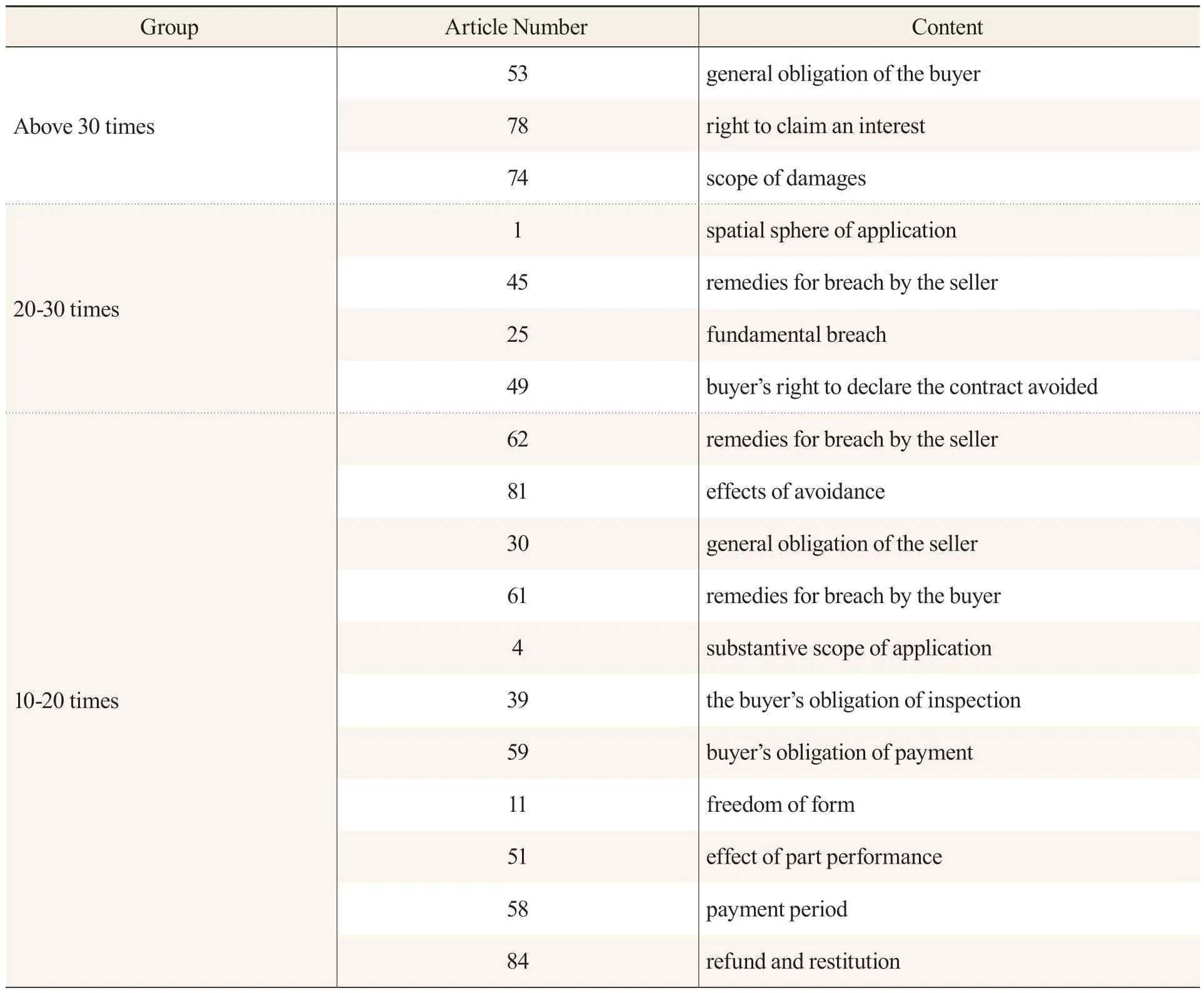

Table 4 Frequency of Provisions Cited

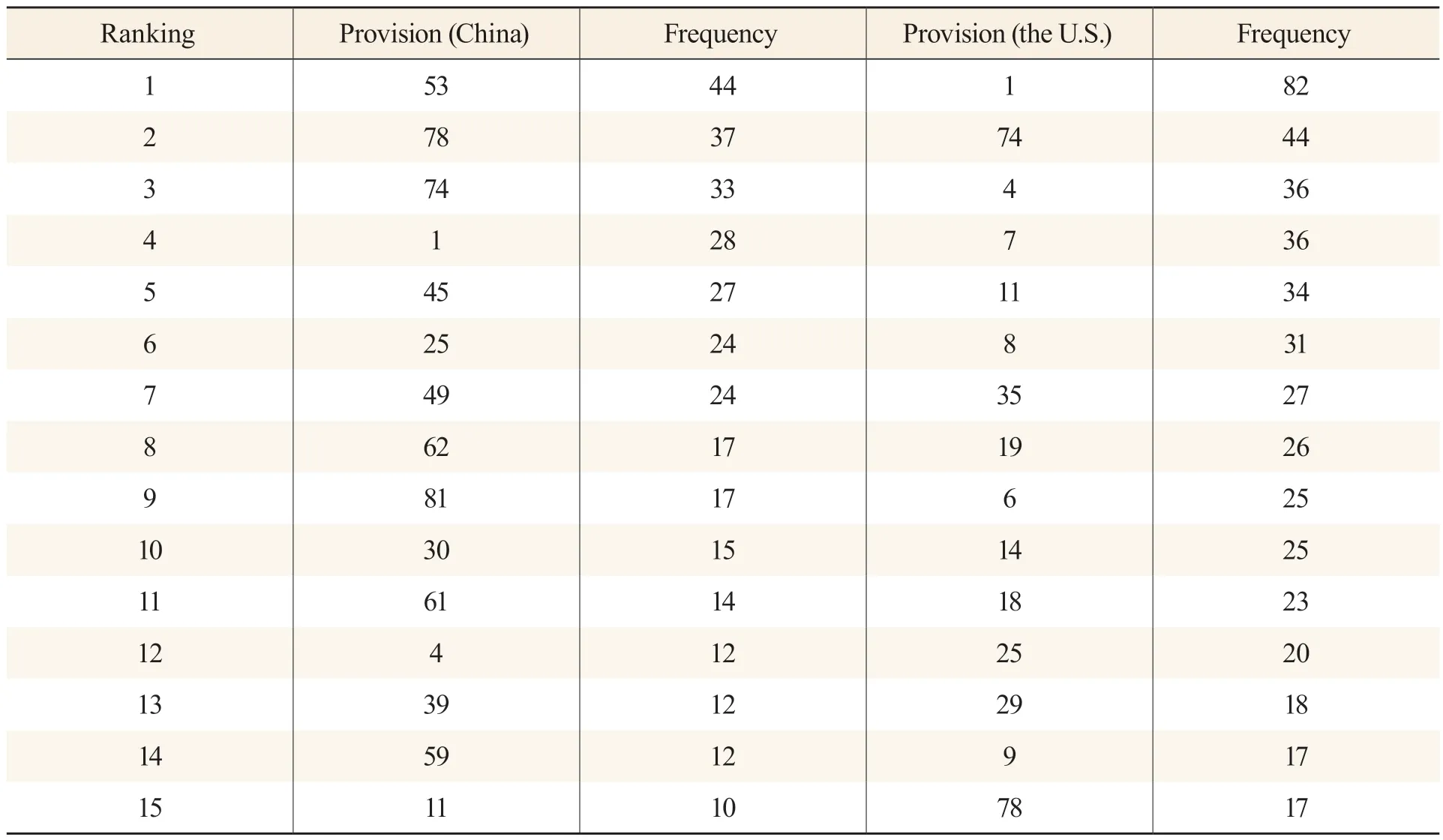

Table 5 A Comparison of China and U.S.Judgments in Citing the CISG Provisions

In these cases, the most significant dispute lies in the party’s autonomous choice of “Chinese law.” According to Art.6 of the CISG, “the parties may exclude the application of this Convention or, subject to Art.12, derogate from or vary the effect of any of its provisions.” The issue here is the valid form to express an exclusion.In the general practice of the CISG, there are two ways for parties to exercise such autonomy.The first and most direct way is to add an exclusion clause that explicitly excludes the application of the CISG.The form of exclusion is governed by the CISG and the intent of the parties shall be determined pursuant to Art.8 of the CISG.The second way is vaguer, namely an explicit choice of a national law.Shall the contract still be governed by the CISG in this scenario? The general practice of the CISG in multiple jurisdictions indicates a positive answer.In the United States, it was ruled in Asante Techs., Inc.v.PMC-Sierra, Inc.that the “Plaintiff’s choice of applicable law generally adopts the ‘laws of’ the State of California,and California is bound by the Supremacy Clause to the treaties of the United States”②Asante Techs., Inc.v.PMC-Sierra, Inc., 164 F.Supp.2d 1142, 1150 (N.D.Cal.2001)A later opinion again emphasizes that a sole exclusion of a contracting state’s law is insufficient “because the CISG is the law of that state.”③Remy, Inc.v.Tecnomatic S.P.A., No.1:11-cv-00991-SEB-MJD (S.D.Ind.Jun.24, 2014)In Switzerland, a federal court recently ruled that “further indications are necessary for an implied exclusion, which clearly and unambiguously indicates a choice of law while excluding the CISG.”④CISG-Online 4463, Retrieved from https://cisg-online.org/search-for-cases?caseId=4463.The guiding case mentioned above (Sinochem International v.ThyssenKrupp) also sets a clear and judicially binding precedence to apply the CISG in the absence of expressed exclusion.

In China, some courts have been taking this “party choice” as a circumventing vehicle from the CISG from time to time.For example, in a second instance, the court reviews and confirms a lower decision on a confusing ground.The court states, “Since the contract in dispute is a contract for the international sale of goods concluded between the parties whose places of business are in the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Türkiye, with both of which as members of the Convention, the dispute arising from the performance of the contract for the international sale of goods between the parties in this case shall be governed by the Convention.Since the Convention gives the parties an option of not applying this Convention, and the parties, in this case, have expressly agreed to apply the law of the People's Republic of China to resolve disputes, and Article 145 of General Principles ofCivil Law of the People’s Republic of China(GPCL) stipulates that the parties to a foreign-related contract may choose the law applicable to the handling of contract disputes.Although it is improper for the court of first instance to directly apply the principle of the closest connection to determine the applicable legal grounds, it was not improper for the court of first instance to apply the laws of the People’s Republic of China as the governing law of this case.”①Civil Judgment (2017) Y MZ No.1119Obviously, the “correction” of first instance itself is not correct, in light of the unequivocal view of “the CISG is Chinese law.” This evading path from the CISG can be abused with a procedure rule of “agreement before the end of the first instance debate,” since the court may indirectly push both parties to agree with the “Chinese law” by raising a vague question without mentioning the CISG.②Civil Judgment (2019) Y 0391 MC No.1932

Another circumventing strategy adopted by some courts is the “false advertising.” In short,the court determines that the CISG shall be the primary governing law with Chinese civil law as a supplementary source to address any gaps or ambiguities.However, in the substantive analysis,no CISG rule is cited or applied.In a recent case, the court recognized at first that “the countries in which the parties have their places of business (the People’s Republic of China and the United Mexican States) have acceded to the CISG.The international treaty shall prevail in the present case.In the absence of clear provisions in the Convention, all parties have chosen to apply the laws of the People’s Republic of China as the applicable law to handle the dispute in this case, and the laws of the People’s Republic of China shall be applied in this case as the applicable law.”③Civil Judgment (2017) Y 0115 MC No.3191But the analysis section of this judgment completely omitted the CISG rules even when the issues(form, price, payment liability) shall be governed by the CISG.This is ade factocircumventing of the CISG.(Besides, this “false advertising” makes more advanced statistic methods less accurate than a limited sample and qualitative analysis).

The Application of Specific Provisions

The typical types of the CISG disputes are limited.Payment (and final balance payment),delivery of goods, goods non-conformity and warranties claim, among other minor points(incorrect remittance, modification of price), are the most frequent issues for disputes.

Based on this distribution of issues, the specific applicable articles become predictable.The following table summarizes the frequently cited articles (≥3 times).The articles are ranked in descending order of citation frequency.

Since the CISG is a default rule for incomplete contracts and the parties may have particular arrangements, the frequency of provisions in court does not necessarily reflect a precise distribution of disputes in the international sale of goods.For example, in the non-conformity disputes, a more detailed and practical standard of quality in the contracts or even negotiation messages may have priority.

However, a comparison with the United States is interesting and reflects the distinguished judicial behaviors when applying the CISG.Based on the previous survey (Arlota & McCall,2023, p.576), the frequency ranking (top 15) of cited provisions in both China and the United States is listed in a descending order as follows.The sample of the United States includes 461 decisions from the time the CISG entered into force until the end of 2019, roughly four times larger in scale than this article.

Considering the size of samples, the first and foremost difference is the Chinese judges’ preference to cite provisions.Within the top-15 range, the size of the U.S.sample is approximately four times larger, while the frequencies of CISG citation are almost uniformly less than twice of its Chinese counterpart.This may be explained by the tradition of stare decisis in common law jurisdictions.

However, as for the CISG applicability, Art.1 of the CISG has been cited by the U.S.judges for outstandingly more times than other clauses, while Chinese judges only make a relatively high reference to it.Such an observation echoes the argument in the second section of this article, that Chinese courts do not always follow the self-reference pattern of Art.1(1)(a).Instead, although Chinese judges generally recognize the priority of the CISG in the absence of explicit exclusion,the motivation might be a policy-oriented one, including the guidance case system and a general atmosphere of pro-CISG.From a legal reasoning perspective, the codification of civil law and the deletion of Art.142 of the GPCL does not prevent Chinese judges from beginning their legal analysis from domestic law.Art.4 of the CISG, the substantive scope of application (a detailed interpretation of “sale of goods”) is in a parallel situation with Art.1.

The third point is about the substantive provisions.Art.74 is popular in both states and governs the specific calculation of damages.This probably means that, for these cases in litigation, the parties hardly design a liquidated damage clause or other calculation method clause in advance.As for differences, for Chinese courts, Art.53 and Art.78 are especially of vital significance.Art.53 is a general and principle-like rule in Chapter III of the CISG, stipulating that “the buyer must pay the price for the goods and take delivery of them as required by the contract and this Convention.” Art.78 is about interests.It states that “If a party fails to pay the price or any other sum that is in arrears, the other party is entitled to interest on it, without prejudice to any claim for damages recoverable under article 74.” It can be observed that both Art.53 and Art.78 are short,general, and qualitative provisions.The following Art.45 (remedy for the breach by the seller) is similar.In fact, the most frequently cited detailed rule in China is Art.49, the multiple grounds for a buyer to declare the contract avoided, which has only half of the frequency of Art.53.Such a preference for general provisions is not unique.The U.S.courts also prefer Art.7, Art.11, and,Art.8, all of which fall under Chapter II (general provisions) of the CISG.

Previous observation over other jurisdictions, especially those with civil law tradition, also reports a higher citing frequency of Art.1 than Chinese courts, which reflects a conscious testing over the judicial applicability of the CISG.For example, Swiss courts generally often cite Art.1,Art.78, Art.74 and Art.4 (Chappuis & Geissbühler, 2017, p.426).This frequency of reference to Art.1 may reflect, to some degree, a matured pattern for judges to follow when considering the judicial applicability of CISG.

Theoretical Comments

As previously mentioned, judicial behavior is conducted in a much more complicated environment than applying a pure legal text.This section embeds the judicial application of the CISG into the Chinese context of legislation and adjudication.The legislation on the judicial applicability of international treaties has been criticized by some researchers (He, 2019, pp.181-192).However, the empirical finding above verifies that the “pro-CISG” attitude, which makes it necessary to find a more comprehensive explanation.The primary answer of this section is that:despite the opaqueness or even absence of guiding norms toward the CISG in domestic law, the judicial and administrative policies probably function as an alternative and promote the “pro-CISG” attitude.Besides, the legal transplantation from the CISG to Chinese civil law has made it a familiar “authority” and thus more accessible than other foreign laws.

Legislation

Previous literature has introduced the history of accepting the CISG in China and its practice within the field of adjudication and arbitration (Liu, 2017, pp.873–918).The first change to be noticed is the codification and updating of Chinese civil law since 2017, which suspends the direct guidance to the CISG.Historically speaking, the Reform and Opening-Up since 1979 has witnessed a dual process for China to join in the international trade, and simultaneously, to construct a dispute resolution system for the domestic market economy.As a result, the nature, difference, related hierarchy, and connection mechanism of international law and domestic law have been a challenge for the newborn and fragile legal community.An example was the debate over the “judicial applicability of WTO Agreements” at the beginning of the 21st century, in which scholars and practitioners debated whether Chinese judges could or should directly apply the WTO treaties in adjudication after Chinese accession (Shi, 2006,p.20).

Theoretically, that and other similar debates might be embedded into a grander picture of “monism vs.dualism” throughout the 20th century (Shelton, 2011, pp.2–3).But from a local perspective, such confusions started from Art.142 of the General Principles of Civil Law of 1986 (GPCL), in which “treaty contract” and “l(fā)aw-making treaty” (and the treaties that turn soft rule into domestic law, or the treaties that are a source of public international law; besides, the self-executing/incorporating treaties or the transformed ones) were not distinguished but mixed as a hodgepodge.Art.142(2) of the GPCL generally stipulates:“If any international treaty concluded or acceded to by the People’s Republic of China contains provisions differing from those in the civil laws of the People’s Republic of China,the provisions of the international treaty shall apply, unless the provisions are ones on which the People’s Republic of China has announced reservations.” In judicial practice,this provision became a clear-cut ground for the judicial application of the CISG.However,problems remain.From the perspective of domestic law, is Art.142(2) of the GPCL only an explicit reaffirmation of the “pacta sunt servanda” principle, or a solid and indispensable basis for the judicial application of international treaties? Besides,Interpretation of theSupreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Law Applicable to Foreign-Related Civil Relationships(I) issued by the Supreme People’s Court in 2013 collocates Art.142(2) of GPCL with Art.95(1) of the Law on Negotiable Instruments, Art.268(1) of the Maritime Law, and Art.184(1) of the Civil Aviation Law, as an expanded scope of conflict rules.Under such circumstances, is Art.142(2) a conflict rule that shares the same hierarchy with The Law of the Application of Law for Foreign-related Civil Relations of 2011 (the private international law of China)? If so, should the referral to the CISG made by Art.142(2) of the GPCL fall into the scope of Art.1(1)(b) of the CISG, which has been paradoxically excluded under China’s reservation? This unclarified question has a practical influence.In a published arbitral award of CIETAC (Diesel Generators case, CISG-online 1454), the tribunal rules that “under Article 142 of the General Rules ofthe Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, the case should be governed first and foremost by the Convention.”①CISG-Online 1454, Retrieved from https://cisg-online.org/search-for-cases?caseId=1454.Similar reasoning can be identified in other published litigation cases.In C&J Sheet Metal Co.Ltd v.Wenzhou Chenxing Machinery Co.Ltd (CISG-online 2821), both Art.142 of the GPCL and CISG Art.1 are held to be the basis for CISG application.②CISG-Online 8735, Retrieved from https://cisg-online.org/search-for-cases?caseId=8735.]In Zhuhai Zhongyue New Communication Technology Ltd.et al.v.Theaterlight Electric Control & Audio System Ltd.(CISG-Online 1610), the court even starts with the principle of “the closest connection” and refers to the application of Chinese law.③CISG-Online 7529, Retrieved from https://cisg-online.org/search-for-cases?caseId=7529.These reasonings are criticized by foreign scholars and deemed as proof that “the path to the CISG is not always without problems” (Kr?ll, Mistelis, & Viscasillas, 2018, p.26).

Probably aware of these troubles, theCivil Codeof 2020 does not include any rule that stipulates or implies the application of international treaties in adjudication.However, without any alternative, such silence may create more uncertainty in legal reasoning when deciding the application.For example, the determination over whether a contract falls into the category of“sale of goods” may trigger a dilemma.Without an initial categorization as the sale of goods,the CISG loses the basis of application; without applying CISG (Chapter I), the “sale of goods”cannot be decided.In this case, should the lex fori apply under the referral of Art.8 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Choice of Law for Foreign-Related Civil Relationships(CLFC), “Lex fori shall apply to the determination on the nature of foreign-related civil relations?.” Another issue is the exclusion of the CISG through party autonomy: Should CISG govern the contractual exclusion of the CISG, especially when it comes to the validity of agreement? Or once both parties agree to exclude the CISG, the court is no longer obliged to review the applicability of the CISG? The challenge originates, partly, from the fact that the CISG itself does not textually claim priority over any domestic rule.But even were there a provision, without an obligation to review CISG, how could a judge be bound by an obligation from the CISG?

All these issues have been leading to mutual-conflicting legal reasonings (discussed as follows) in court decisions.Behind these puzzles lies a philosophical (to be more specific,a hermeneutical) paradox of “Münchhausen trilemma” (Lodder, 1997, pp.205–206), which unveils the universal impossibility of making a solid argument with pure knowledge premises,since any premise must be grounded elsewhere (e.g., a general principle or a similar practice in other jurisdictions), and the infinite pursuit for a deeper ground will end up either referring to a void or referring to itself.Therefore, such a circular argument, or as a metaphor, an attempt to pull oneself up by one’s own bootstraps, is a philosophically doomed attempt.The international law community is familiar with this insight.Though mainly focusing on public international law, the Critical Legal Theory has already contributed an idea here, that international law,which emphasizes norms, can be boiled down to mutually exclusive interpretations, or the“l(fā)egal arguments” (Koskenniemi, 2006, p.58).The Law and Social Science Movement, with an experimental methodology, goes even further into judicial behaviors in general, pointing out that the “technique for rationalizing biased decisions” is the nature of legal reasoning (Li & Liu,2019, p.630).

Policy

These being argued, cases must be decided.A second-best solution in legal practice is also to cut up the infinite logical referral unnoticeably with a judicial policy.A successful example is the “competence-competence doctrine” in international commercial arbitration (Bonn, 2012,p.52).When piercing the veiling of legal terms, the real source of the tribunal’s competence is surely not a simple self-claiming word.Instead, the mandate power of the tribunal is ultimately borrowed from the state in the enforcement jurisdiction under the New York Convention of 1958, behind which lies the member states’ willingness to join in trade competition as an alternative to military plunder, which had led to the suffering of two world wars.For the CISG,similar to the obligation of acknowledging and enforcement in the international arbitration,the solution of paradox is also to indisputably oblige judges with a duty to look into the CISG applicability once a prima facie clue of international sale of goods emerges.

Wherever the statutory law ends, another form of policy shows up (Clune, 1993, p.8).In the absence (or impossibility) of clear legislation for “why looking into the CISG for the first glance,” the guiding case system becomes an alternative.Recent research has introduced the fact, issue, conclusion, and influence of the Guiding Case No.107, Sinochem International(Overseas) Pte Ltd v.ThyssenKrupp Metallurgical Products GmbH (Liu, 2021, p.339).The Supreme People’s Court decision still starts from conflict rules and confirms the parties’choice of law (New York law) as valid.Then it clarifies that the CISG is not excluded by an agreement of applying a contracting state’s law.Such a reasoning is probably doubtful from a comparative perspective, since Art.1(1)(a) makes the application of the CISG “automatic,”and “direct” (Kr?ll, Mistelis, & Viscasillas, 2018, p.35).In fact, the Supreme People’s Court in 2019 (the original decision was made in 2014) also points out that for this case “the CISG shall have priority” and “a choice of a contracting state’s law is not an implied exclusion of the CISG,” which is slightly deviated from the original court decision.Besides this legally binding case, other “typical cases” selected and published for reference by both the Supreme People’s Court and other lower courts also stick to the pro-applicability line.In February 2022 and September 2023, the Supreme People’s Court published the third and fourth batches of typical cases with international and commercial issues related to the “Belt and Road Initiative,” both including a CISG case.For example, in Exportextil Countertrade, S.A v.Nantong Mcknight Medical Products Co., Ltd, 2019, the Nantong Intermediate People’s Court directly holds that since the Chinese party and Spanish party did not explicitly exclude the CISG, the CISG shall apply.These cases are mostly selected from local courts’ reports through internal channels or from public white papers, which help to build an active and competent image of local courts in the response to the judicial policy of the Supreme People’s Court.

The rationale behind such a CISG-supporting policy might be more than a pure legal conclusion.In foreign-related policies, the judicial system also has an advantage of flexibility among power branches, turning conflicts into legal, technical, and finally verbal issues.In 2015, the Supreme People’s Court issued a policy, Several Opinions of the Supreme People’s Court on Providing Judicial Services and Safeguards for the Construction of the “Belt and Road” by People’s Courts, which relates the duty “to continuously improve the ability to apply international conventions” with the aim of “eliminating the legal doubts in the international business conducted by the parties in the countries along the Belt and Road area,” which finally and politically contributes to the “holy duty” and “contemporary commission” of judicial systems in the initiative.Previous studies also pointed this out (Guo & Zhang, 2020, p.235).In October 2022, Zhou Qiang, the then President of the Supreme People’s Court, addressed the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.His speech, Report of the Supreme People’s Court on Foreign-related Trial Work of the People’s Courts, also emphasized the“perfection of international commercial dispute resolution” as a means to establish a “marketbased, international, and rule-of-law business environment.” which follows the party’s line of Deepening the Reform and Opening-up, since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.The achievements and performance mentioned by Zhou Qiang include the application of foreign law and international treaties (Zhou, 2022).

Judicial Practice

Beyond legislative and policy background, the judicial practice is another important context.The workload of judges has been known to be overwhelming since the establishment of personnel quota system in 2017, while litigation has been surging more than 40 times during the past four decades of marching “towards a more litigious society” (Gu, 2021, p.53).Meanwhile,the professionalization of judges cannot be achieved overnight, especially when it comes to the unfamiliar and complicated foreign-related cases.Under the pressure of being accounted over misjudged cases (Sun & Fu, 2022, p.867), the lower courts and judges then developed several alternative strategies, such as resorting to the difficulty of finding out and ascertaining foreign law, or transferring the jurisdiction to the upper level of courts.Within this stressful background, the familiarity of the knowledge of a certain law can be a reasonable factor that influences the judges’ willingness to apply it in cases.

This gap of knowledge may partly explain the distinguishingly high rate of applying the CISG against other foreign laws.China ratified the CISG in 1986, which was 13 years before theContract Law of 1999.This is different from the cases in most developed countries, where the domestic contract law has been practiced for many more decades than the CISG.The profound influence of the CISG upon Chinese civil law legislation is widely acknowledged.In this sense, the CISG is not only an incorporated part of Chinese law, but also a background and a prototype of it.For specific rules, such transplantation can be found in “the conclusion of the contract, termination, liabilities for breach (damages and price reduction), exemption and sales contracts (remedies for nonconformity, rules on risk),” among some other details(Han, 2012, p.247).The codification does not alter this knowledge landscape (Guo et al.,2021, p.192).

To understand why this transplantation possibly becomes a bonus for latecomers, it is necessary to make comparisons.An opposite example is the competition between British contract law and the CISG.In the UK (a non-contracting state), the education of the CISG is insufficient and the acceding proposal to the CISG has been gaining inadequate support from the lawyers who have developed a path-dependence and vested-interests by relying on the British contract law and maritime law in the international trade (Rogowska, 2011, p.13).In Germany, as a contracting state for over 30 years, the established tradition of domestic civil law since 1900 is of even longer pride.In 2005, 42 percent of the German lawyers regularly exclude the CISG in contracts and 30 percent “exceptionally or accidentally” apply the CISG (Meyer,2005, p.485).A recent survey shows that most German law firms (63.2 percent) prefer German law with the exclusion of the CISG, which means the CISG “is still far from receiving the attention or acceptance it actually deserves” (Lehnert & Sch?fer, 2021, p.146).In the U.S., the lawyers who are unfamiliar with CISG tend to regard it as “foreign law” (Fitzgerald, 2008, p.34).Russian lawyers also observe “that many foreign partners, especially those from Germany and Switzerland, insist on the exclusion” of the CISG (Shirvindt, 2017, p.387).Meanwhile, even taking theLaw of the People’s Republic of China on Economic Contracts Involving Foreign Interest(1985) into consideration, the Chinese domestic legislation was almost at the same pace as the acceding of CISG (1986).Such a tabula rasa scenario makes it possible for legislators to consider the CISG as a model and for legal practitioners to get rid of the path-dependence of domestic law.Such a linkage between legal transplantation and the CISG practice can also be verified with its spillover effect.During the collection, the author of this article finds 11 special cases in total, in which at least one party resorted to the CISG for complaining or answering.These cases, surprisingly, are pure domestic ones and irrelevant to the international sale of goods.The role of the CISG is a supportive argument in terms of the interpretation of certain terms.

A usual scenario of this practice is the legal dispute in the second instance or higher reviews.The party that challenges the lower court’s decision may unilaterally introduce the CISG into the discussion over a key issue on the battlefield.The most common issue is about the interpretation and identification of a “fundamental breach.” In a commercial estate tenancy case in 2014, the retrial applicant (the owner of the estate) claimed that the commissioned leasing agent had failed to fulfill the advertising and rent-promotion duty agreed in the contract,resulting in a loss of more than 800,000 RMB.Additionally, the agent rented out some shops without permission to pocket the forfeited money.The goal of the applicant is to terminate the contract on the ground of “fundamental breach.” For this purpose, the applicant cites Art.94(4)of theContract Law of 1999, “...one of the parties delays the performance of the debt or has other breaches of contract, resulting in the failure to achieve the purpose of the contract.” Then the applicant argues through a direct citation of the CISG Art.25.With this as a premise, the claimant deducts that, “...what he is entitled to expect under the contract...” is obviously to rent out the shops, so that the shopping center may flourish, and the applicant obtains rental income.However, according to the proven fact, less than 30% of the area of the first year of the agent has been rented out.Therefore, the agent conducted a fundamental breach and the contract should be terminated.①Civil Judgment (2014) SZFSJ MZ No.1The CISG rule of fundamental breach is borrowed as if it were a natural law.The respondent of a similar case in 2018 goes even further by simultaneously citing Art.48 and interprets it as “...the Convention allows the seller to remedy its breach at its own expense,either before or after the performance period has expired, unless such remedy is unreasonable for the buyer so that even if the breach is serious, it does not constitute a fundamental breach if the breach can be remedied.”②Civil Judgment (2018) C 01 MZ No.9839Such an argument about “remediable means non-fundamental” is not necessarily persuasive and the court reasonably refuses to apply the CISG.But the tendency to take the CISG as a reliable authority is clear.

Exceptionally, the court also proactively borrows the CISG as a comparative-law argument.In a rural land contracting dispute in 2014, the villagers’ committee (representing the collective ownership of rural land) filed a suit against a villager who had subcontracted a reservoir for aquaculture.The subcontractor later grew maize in the dried reservoir due to damage in the dam.The committee sought to terminate the contract on the grounds of fundamental breach.Without any claim by parties, the court decides that “fundamental breach of contract is not a concept adopted by Chinese contract law, but a concept that originated from the common law of the United Kingdom and the United States.At the same time, Art.25 of the CISG also provides the rule.Corresponding to the relevant provisions of Chinese Contract Law, the so-called fundamental breach of contract means that one party fails to perform or delays the performance of the main debt, resulting in the other party being unable to achieve the purpose of the contract.”①Civil Judgment (2014) YY MC No.123This case in Jilin Province not only confirms the image of CISG as a comparative source, but also shows the wide influence of CISG in China.Instead of being limited to those modern, coastal, and urban disputes, the imported knowledge of CISG disseminates and permeates into local dispute resolutions.

This unexpected case of the spillover effect of the CISG is not an isolated one.In a landlocked province, Gansu, in 2018, a window installing worker appealed to the court for an unpaid fee.His reasoning is, that “the effect of an offer is that the contract can be formed once the offeree has accepted it.Article 14 of the CISG provides that a proposal to conclude a contract addressed to one or more specified persons constitutes an offer if it is sufficiently certain and indicates the intention of the offeror to be bound upon acceptance …”

These examples reflect the influence of the CISG in China.Under the general difficulty of finding and ascertaining foreign law in Chinese adjudication, the CISG becomes a rather unique success.In short, such “pro-CISG” attitude in judicial practice should be understood beyond the legal texts: in the absence of clear guidance from the “l(fā)aw in book,” other factors may be an alternative.This does not refuse any effort toward legislation improvement, but reminds us to coordinate multiple efforts, which makes judges not only obliged to apply a certain law, but also willing to do so.

Last but not least, to describe the application of CISG in China as a “success” does not mean that it is out of defect.In fact, despite the pro-CISG attitude in general, the erroneous decisions and the homeward trend have not been eliminated.Even in the reputable frontiers of international trade and dispute resolution, confusing decisions are sometimes fabricated.For example, a court holds that “the case was a dispute over an international purchase and sale of goods.According to the conflict law...the parties in this case may choose the applicable law.Since the parties did not agree on the application of law, this court applied the principle of closest connection in accordance with the law, and the law of the People’s Republic of China shall be the governing law.” The court then directly applies Chinese contract law, without any comment on the CISG.②Civil Judgment (2019) Y 0391 MC No.338

Another unpersuasive reasoning made in a coastal province, Fujian, is even less acceptable.The court decides that “the defendant in this case, is a foreign enterprise in Singapore, and the plaintiff has a dispute over the sale of goods … If the parties did not agree upon the applicable law, the law of the seller’s location shall apply in accordance with Article 8 of the CISG.In other words, the law of the People’s Republic of China shall apply in this case.”①Civil Judgment (2015) Z MC No.457Obviously,the judge has a basic knowledge of the CISG and correctly conducts ade factoArt.1(1)(a) test.Nonetheless, any textual reading will indicate that Art.8 of the CISG treats the issue of intent interpretation and mentions nothing about “the law of seller’s location.” The similarity of these two examples, among several other cases, is the absence of the defendant party before the court.In other words, the litigations are in essence a confirmation of debt.As a result, the judges are under less pressure to face appeals and other complaints.Again, this behavior suggests that judges are not always ideal followers of the law in book, but rather occasionally take advantage of convenient shortcuts.

All these imperfect cases indicate that, to unify and clarify the guiding rule of applying international treaties in adjudication might be indispensable.Just as Prof.Liu Ying and Dr.Yang Mengsha commented, “the most fundamental solution is to stipulate the direct application of civil and commercial treaties” in the domestic law (Liu, 2019, 191), and the priority of the uniform law in the international commercial treaties should be embodied in a clearer way (Yang,2020, p.97).

Conclusion

This article locates the CISG judicial applicability into an evidence-based and comparative context.The initiative question derives from the unique contrast in China between a rather vague legislation and the “pro-CISG” image depicted by previous studies.To settle this puzzle,a two-step analysis is adopted to inquire into the “how” and “why” of the judicial applicability of the CISG in China.For the empirical section focusing on “how,” the basic finding is that,the pro-CISG attitude in Chinese litigations is verified, compared with other applicable foreign laws in Chinese international litigations, as well as with the application of the CISG before U.S.courts.But the picture is more complicated than a story of “judges follow the law.” For the theoretical explanation section, a contextualized analysis shows that, despite the vagueness of domestic legislation, the judicial policy promotion, the innovative guiding cases system, the legal transplantation as a knowledge background, and other factors may contribute to the “pro-CISG” in China.

The main contributions of this article are the updated dataset, the qualitative comments,and an attempt to apply the perspective of social sciences to pierce through the legal texts.The basic insight of this research is that, a pure legislation that claims the judge’s obligation to apply a certain norm, is of significance but may not be adequate.The willingness and capacity of judges, as rational persons who react to policies and other environmental factors, should not be ignored when promoting the application of international uniform rules.

Confined by the limited sample, further interpretive analysis (especially the causal inference) in terms of the motivation, deciding factors, and the effect of CISG application remains to be treated in future works.The ultimate goal of this research can be a theoretical framework of judicial behaviors related to international rules in the commercial litigations.

The practical implication of this and future research are expected to be substantial.The amendment toCivil Procedure Lawin 2023 expands the competence of Chinese courts in terms of international litigations.TheProvisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning Jurisdiction over Foreign-Related Civil and Commercial Cases,enforced since 2023, removes thede factojurisdiction centralization in Intermediate People’s Courts.These changes might make the inexperienced and overloaded judges in lower-level courts face more challenges.The story of “pro-CISG” in China may serve as a reminder,that the law operates both as texts and as actions and that the legislation improvement and other factors may coordinate in the promotion of an open system of transnational dispute resolution.

Contemporary Social Sciences2023年6期

Contemporary Social Sciences2023年6期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- The Modernization of Traditional Chinese Opera and a Local Perspective of Local Operas: A Case Study of the Research on the Yisu Art Troupe by Li Youjun and Guo Hongjun

- Reflections on, and Improvements of,the Mediation Functions of People’s Assessors

- Impact of Mandatory Provisions on the Validity of Juristic Acts: A Path for Legal Policy Analysis

- Promoting the International Dissemination of Chinese Culture Through International Chinese Language Education: A Case Study of Chinese-English Idiomatic Equivalence

- RMB Exchange Rate, Overseas Education, and High-Quality Economic Growth

- Research on the Chinese Path to Modernization in History, Key Topics,and Outlook: A CiteSpace-based Bibliometric Analysis