Percutaneous ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of solid pancreatic lesions: An analysis of 1074 lesions

Wei-Lu Chi , Xiu-Feng Kung , Li Yu , d , Cho Cheng , b , Xin-Yn Jin , b , Qi-Yu Zho , b ,Tin-An Jing , b, c,*

a Department of Ultrasonography, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

b Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

c Key Laboratory of Pulsed Power Translational Medicine of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou 310 0 03, China

d Department of Ultrasound, Taizhou Hospital, Taizhou 3170 0 0, China

ARTICLE INFO Article history:Received 7 March 2022 Accepted 28 June 2022 Available online 4 July 2022

Keywords:Pancreatic Biopsy Fine needle aspiration Ultrasound Endoscopic ultrasound

ABSTRACT Backgrounds: Percutaneous ultrasound (US) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided pancreatic biopsies are widely accepted in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Studies comparing the diagnostic performance of US- and EUS-guided pancreatic biopsies are lacking. This study aimed to evaluate and compare the diagnostic yields of US- and EUS-guided pancreatic biopsies and identify the risk factors for inconclusive biopsies.Methods: Of the 1074 solid pancreatic lesions diagnosed from January 2017 to February 2021 in our center, 275 underwent EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), and 799 underwent US-guided core needle biopsy (US-CNB/FNA). The outcomes were inconclusive pathological biopsy, diagnostic accuracy and the need for repeat biopsy. All of the included factors and diagnostic performances of both USCNB/FNA and EUS-FNA were compared, and the independent predictors for the study outcomes were identified.Results: The diagnostic accuracy was 89.8% for EUS-FNA and 95.2% for US-CNB/FNA ( P = 0.001). Biopsy under EUS guidance [odds ratio (OR) = 1.808, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.083-3.019; P = 0.024], lesion size < 2 cm (OR = 2.069, 95% CI: 1.145-3.737; P = 0.016), hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.274,95% CI: 0.097-0.775; P = 0.015) and non-pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma carcinoma (PDAC) diagnosis (OR = 2.637, 95% CI: 1.563-4.449; P < 0.001) were identified as factors associated with inconclusive pathological biopsy. Hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.236, 95% CI: 0.064-0.869; P = 0.030), lesions in the uncinate process of the pancreas (OR = 3.506, 95% CI: 1.831-6.713; P < 0.001) and non-PDAC diagnosis(OR = 2.622, 95% CI: 1.278-5.377; P = 0.009) were independent predictors for repeat biopsy. Biopsy under EUS guidance (OR = 2.024, 95% CI: 1.195-3.429; P = 0.009), lesions in the uncinate process of the pancreas (OR = 1.776, 95% CI: 1.014-3.108; P = 0.044) and hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.127, 95% CI:0.047-0.347; P < 0.001) were associated with diagnostic accuracy.Conclusions: In conclusion, both percutaneous US- and EUS-guided biopsies of solid pancreatic lesions are safe and effective; though the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA is inferior to US-CNB/FNA. A tailored pancreatic biopsy should be considered a part of the management algorithm for the diagnosis of solid pancreatic disease.

Introduction

Image-guided biopsy is a widely accepted technique, which has excellent diagnostic accuracy, and directs the subsequent therapy of solid pancreatic lesions. Percutaneous ultrasound (US) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) are the main guiding modalities for pancreatic biopsy because of the real-time multiplanar scanning capabilities and the lack of radiation exposure. A previous study demonstrated that percutaneous US-guided pancreatic core biopsy and fine needle aspiration (FNA) have very similar efficacy and safety profiles, and there are no significant differences in diagnostic performance according to lesion location or biopsy type [ 1 , 2 ].Small and poorly visible tumors on US are inaccessible during trans-abdominal biopsy. EUS is particularly useful for the detection of small pancreatic lesions, and the previously reported sensitivity of EUS scanning for pancreatic lesions is superior to that of trans-abdominal US and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) in cases where the target tumor is smaller than 20 mm (94% vs. 67%) [ 3 , 4 ]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines stated that EUS-FNA has a better diagnostic yield, better tolerability and potentially lower risk of peritoneal seeding than the percutaneous approach [ 4 , 5 ]. It has been reported that EUS-FNA has an overall sensitivity of approximately 75% to 98%, specificity of 71% to 100%, and accuracy of 79% to 98% for diagnosing pancreatic masses [6-9] . However, with the EUS approach, the specimens aspirated by fine needles are somewhat unsatisfactory, and core needle biopsy (CNB) specimens could theoretically overcome the FNA-related limitations. CNB provides a well-preserved tissue structure for histologic evaluation [ 10 , 11 ].A hybrid approach for pancreatic biopsy seems appropriate. Studies comparing the diagnostic performance of percutaneous US- and EUS-guided pancreatic biopsies are lacking. Therefore, we carried out this study to evaluate and compare the diagnostic performance of percutaneous US- and EUS-guided pancreatic biopsies in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic disease and identify the risk factors for inconclusive biopsies.

Methods

Patient population

The clinical, radiological and pathological data of 1033 patients with 1074 solid pancreatic neoplasms from January 2017 to February 2021 who underwent pancreatic biopsy under US and EUS guidance in our center were analyzed. All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of medicine and with the1964HelsinkiDeclarationand its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Of the 1074 solid pancreatic lesions, 275 underwent EUS-FNA, and 799 underwent US-CNB/FNA. Three levels of operators performed the US- or EUSguided pancreatic biopsies: level 1 included abdominal and interventional radiologists with less than 5 years of experience; level 2 included abdominal and interventional radiologists with more than 5 years but less than 10 years of experience; and level 3 included abdominal and interventional radiologists with more than 10 years of experience. All of the included solid pancreatic lesions were assessed by at least two imaging modalities, and the biopsy approach was previously determined by level 3 operators and pancreatic specialists. The exclusion criteria were as follows:(1) clinical and laboratory tests suggesting potential acute pancreatitis or recurrent chronic pancreatitis; (2) severe clotting impairment (platelet count<50 × 109/L or international normalized ratio>2); (3) multiorgan failure; (4) suspicious gastrointestinal perforation; (5) thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm; and (6) acute intracerebral hemorrhage.

US-CNB/FNA

An ultrasound system (Aloka, Tokyo, Japan; Mindray, Shenzhen,China; Esaote, MyLab 9, Florence, Italy) with an ultrasound transducer (3.5 MHz convex array probe) was used for navigation and monitoring during percutaneous pancreatic biopsy by either CNB or FNA. An automated gun (Magnum Bard, Covington, GA, USA) either directly or with the coaxial technique was used in CNB, and an aspiration needle (HAKKO medical, Osaka, Japan) was used in FNA. After sterilizing the skin and the trans-abdominal needle tract with 1% lidocaine, an 18G automated cutting needle was used to puncture the skin and was advanced to the target pancreatic lesion by using the free-hand technique. When the abdominal structures prevented direct puncture to the target lesion, a trans-gastric,trans-spleen or trans-colon approach was selected accordingly. After pulling the trigger, specimens were taken and then fixed in 10% formalin. Generally, the specimen was 19 mm in length and 1 mm in width. If the sample was insufficient or the appearance of the tissue did not conform to the pancreatic tumor, an additional puncture was immediately performed. For the FNA procedure, an 18G or 21G aspiration needle was advanced to the target pancreatic lesion. When the tissue was successfully aspirated, parts of the samples were immediately smeared on glass slides and fixed with 95% alcohol for cytopathology, and the tissue was fixed for histopathology. The puncture site and tract were routinely checked for bleeding or other complications. A gelatin sponge was inserted through the coaxial needle if there was evidence of bleeding at the puncture site.

EUS-FNA

All EUS-FNA procedures were performed using a linear-array echoendoscope (GF-UCT240, Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo,Japan) with 19G to 25G needles (Echotip, Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA), while 22G was the most commonly used in our study.Once the pancreatic lesion was localized and the echoendoscope was positioned, the needle type was selected according to the surrounding structure and the experience of the operators. After inserting the needle into the target lesion through the echoendoscope, the “slow-pull” stylet suction and 5 mL syringe suction technique were used to aspirate the tissue under the real-time visualization of EUS. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) was not conducted in our hospital. The number of biopsy passes was determined based on the requirements of the aspirated specimens. Cytology and histology preparations were combined to improve the diagnostic yield and increase the sensitivity for cancer detection.When the solid tissue was aspirated, a small amount of tissue-rich aspirate fluid was transferred to clean glass slides, and two mirrorimage smears were made per pass; these slides were immediately stored in ethanol (smear cytology, SC). For liquid-based cytology(LBC), the biopsied needle was rinsed in a single vial containing ThinPrep at the end of FNA. The aspirated tissue was fixed in a formalin solution for further staining and examination.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) with SonoVue (contrast agent, Bracco, Milan, Italy), which helped to evaluate the vascularization of the target lesion, was usually performed before pancreatic biopsy with either US or EUS guidance. The contrast agent was supplied as a lyophilized powder and reconstituted with 5 mL of saline to make a homogeneous microbubble suspension; 2.4 mL of this suspension was administered per bolus, followed by a 5 mL physiologic saline flush.

Biopsy details and outcomes

The baseline demographic data documented in the electronic medical records were collected. The radiological characteristics and biopsy details of each pancreatic lesion were digitally recorded as Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data and examined by operators and assistants. The major complication of pancreatic biopsy, which was defined according to Quality Improvement Guidelines for Percutaneous Needle Biopsy of the Society of Interventional Radiology, included bleeding requiring transfusion or intervention, prolonged hospitalization, requiring major therapy, unplanned increase in level of care, and permanent adverse sequelae or death [ 12 , 13 ]. All the cytologic samples were stained and evaluated by experienced cytopathologists (with more than 15-year experience in pancreatic disease) in our center. The biopsy specimens were collected and stored according to standard techniques in the pathology department of our hospital.Two pathologists with more than 20 years of experience in pancreatic disease made the histological diagnosis. The specialists in the pathology department discussed the inconclusive results and complicated cases submitted by the primary diagnostic pathologists. The final diagnosis/decision was made based on the surgical pathology, repeat biopsy pathology, clinical course or at least 6-month clinical and imaging follow-up data. The main outcomes were the diagnostic performance of each method, including diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value,negative predictive value and Youden index. The other outcomes of our study were inconclusive pathological biopsy and the need for repeat biopsy. All of the included factors and diagnostic performances of both US-CNB/FNA and EUS-FNA were compared, and the independent predictors of the study outcomes were identified.

Statistical analysis

The differences in categorical variables between the EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA groups were estimated by Pearson’s Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Normally distributed variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD)and were compared by the Student’st-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (range), and were compared by nonparametric test. The meaningful independent predictors were identified by multivariate logistic analysis. APvalue<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 1076 lesions of pancreatic biopsies were performed in our study; the procedural success rate was 99.8%, and the two failed cases were excluded. The data of twelve cases were missing, and the final diagnoses were determined according to the discharge record. The biopsied pathology revealed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma carcinoma (PDAC), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas (SPT),inflammation, other malignancies, inconclusive results and benign tumors. One case of duodenal perforation occurred in the EUSFNA group, one case of delayed gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm and five cases of puncture associated pancreatitis in the US-CNB/FNA group. The major complication rate was 0.4% in the EUS-FNA group and 0.8% in the US-CNB/FNA group (P= 0.685).

The diagnostic performance of EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA

The diagnostic accuracy was 89.8% in the EUS-FNA group and 95.2% in the US-CNB/FNA group (P= 0.001). The sensitivity,specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and Youden index were 89.7%, 91.7%, 99.6%, 28.9% and 81.4%, respectively in the EUS-FNA group and 95.3%, 85.7%, 99.9%, 14.0% and 81.0%, respectively in the US-CNB/FNA group. The lesion size<2 cm (26.5% vs. 6.9%,P<0.001), hypoechoic appearance (95.6% vs.99.1%,P<0.001), ill-defined boundary (73.8% vs. 80.7%,P= 0.015),non-PDAC diagnosis (22.5% vs. 12.5%,P<0.001), inconclusive pathological biopsy (12.7% vs. 5.4%,P<0.01), inaccurate diagnosis(10.2% vs. 4.8%,P= 0.001), repeat biopsy (6.2% vs. 3.0%,P= 0.018)and application of CEUS (39.6% vs. 73.1%,P<0.001) were significantly different between the EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA groups( Table 1 ).

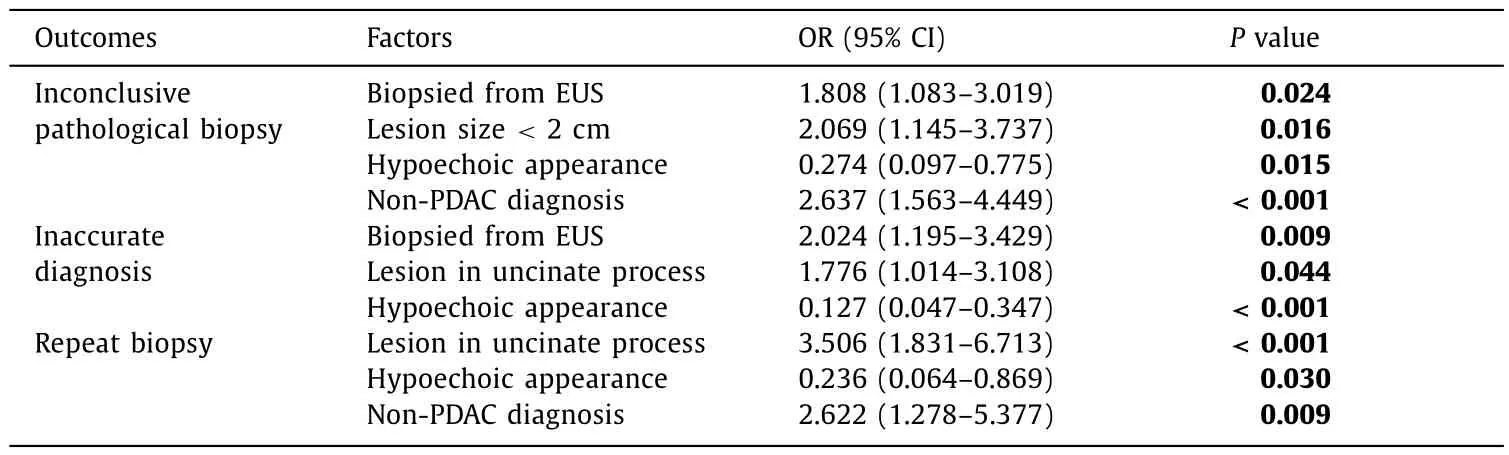

Predictors for outcomes

The total rate of inconclusive pathological biopsy was 7.3%, the rate of repeat biopsy was 3.8%, and the rate of pathologic diagnosis inconsistent with the clinical result was 6.1%. Biopsies performed under EUS guidance [odds ratio (OR) = 1.808, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.083-3.019;P= 0.024], lesion size<2 cm(OR = 2.069, 95% CI: 1.145-3.737;P= 0.016), hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.274, 95% CI: 0.097-0.775;P= 0.015) and non-PDAC diagnosis (OR = 2.637, 95% CI: 1.563-4.449;P<0.001)were identified as factors associated with inconclusive pathological biopsy. Hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.236, 95% CI: 0.064-0.869;P= 0.030), lesions in the uncinate process of the pancreas(OR = 3.506, 95% CI: 1.831-6.713;P<0.001) and non-PDAC diagnosis (OR = 2.622, 95% CI: 1.278-5.377;P= 0.009) were independent predictors for repeat biopsy. Biopsies performed under EUS guidance (OR = 2.024, 95% CI: 1.195-3.429;P= 0.009), lesions in the uncinate process of the pancreas (OR = 1.776, 95% CI: 1.014-3.108;P= 0.044) and hypoechoic appearance (OR = 0.127, 95% CI:0.047-0.347;P<0.001) were deemed independent predictors for an inaccurate diagnosis ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Factors for inconclusive pathological biopsy, repeat biopsy and inaccurate diagnosis.

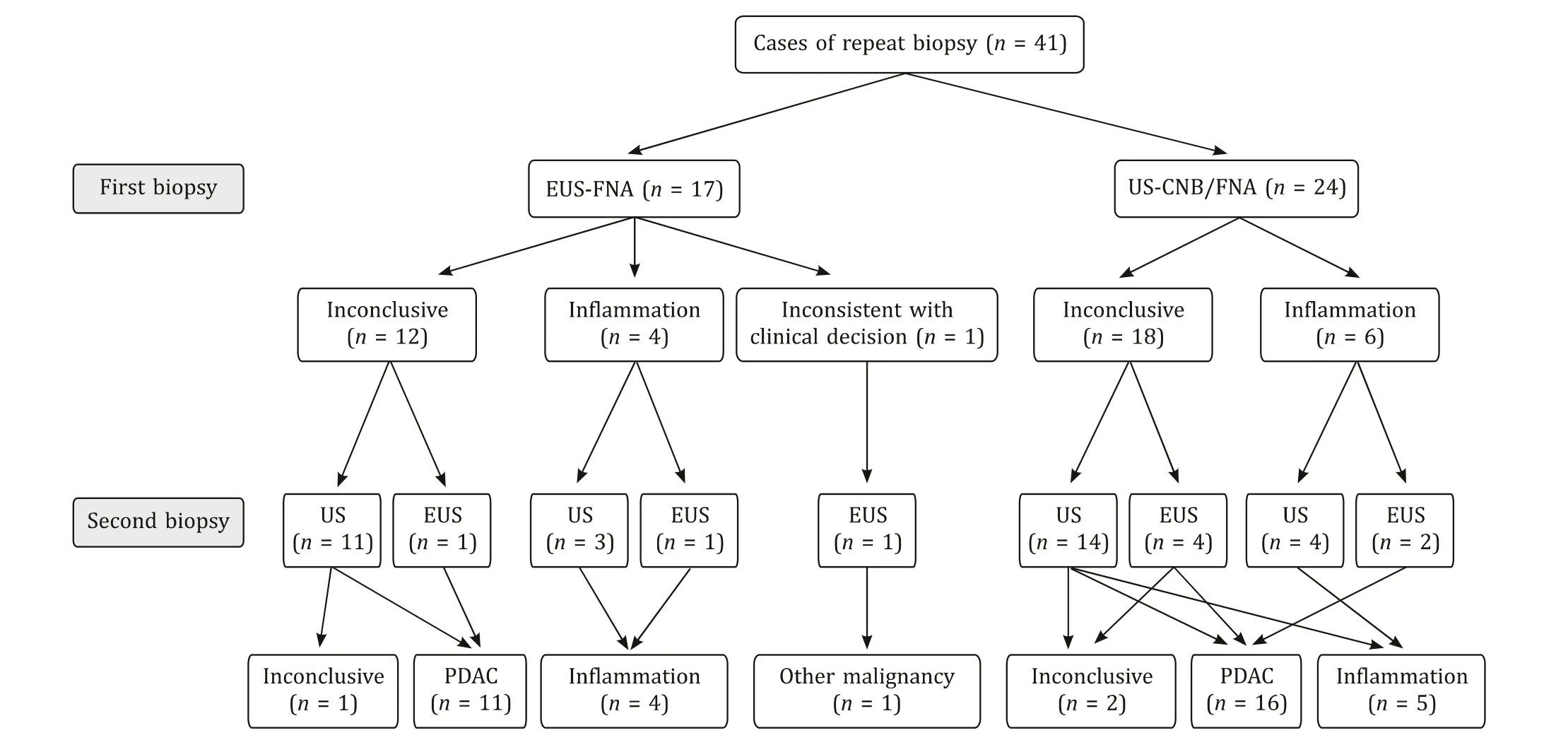

The rate of repeat biopsy was 6.2% in the EUS-FNA group and 3.0% in the US-CNB/FNA group. The details of the 41 repeated cases are shown in Fig. 1 . Among the repeat biopsies, the rate of inconclusive pathological biopsy was 7.3%, which was equal to the rate of primary pancreatic biopsy.

Fig. 1. The details of the 41 patients who underwent repeat pancreatic biopsy. EUS-FNA: endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration; US-CNB/FNA: ultrasoundguided core needle biopsy/fine needle aspiration. PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

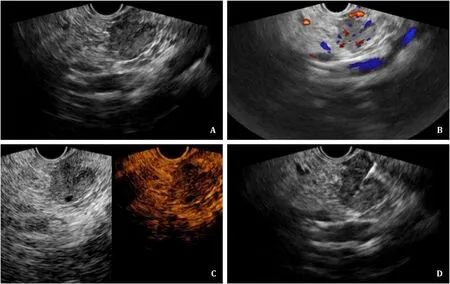

Fig. 2. A: Under EUS scanning of the duodenum, a hypoechoic lesion in the uncinate process of the pancreas was visualized, with the longest length measuring 1.9 cm. B:The color signal within and surrounding the lesion was detected. C: CE-EUS suggested that the lesion was heterogeneously hyper-enhanced in the arterial phase and slightly enhanced in the venous phase. D: A 22G needle was inserted into the lesion, and the tissue was aspirated under the real-time guidance of EUS. The pathological biopsy suggested that the lesion was a PNET, which was consistent with the clinical presentation and surgical pathology. EUS: endoscopic ultrasound; CE-EUS: contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound; PNET: pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

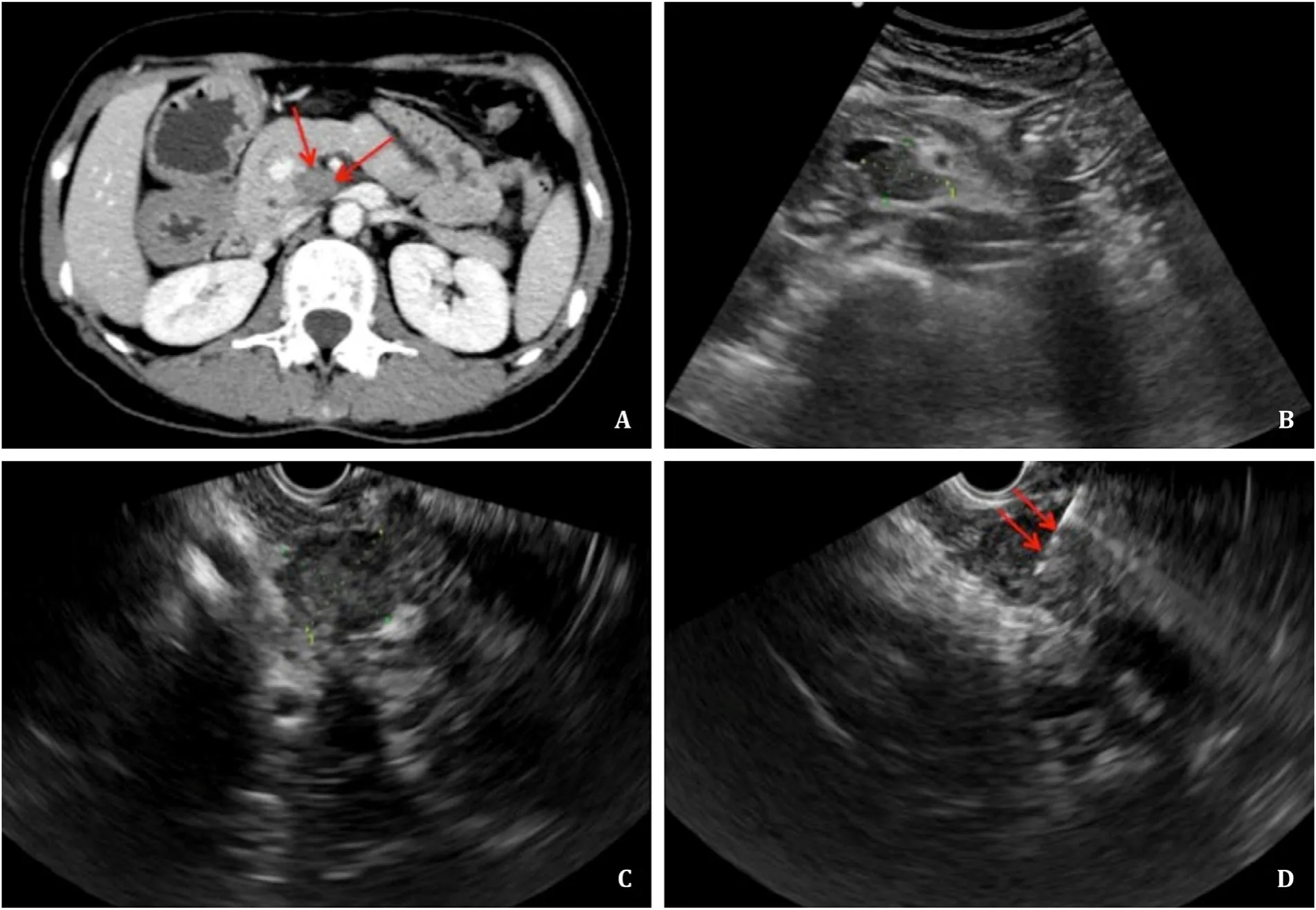

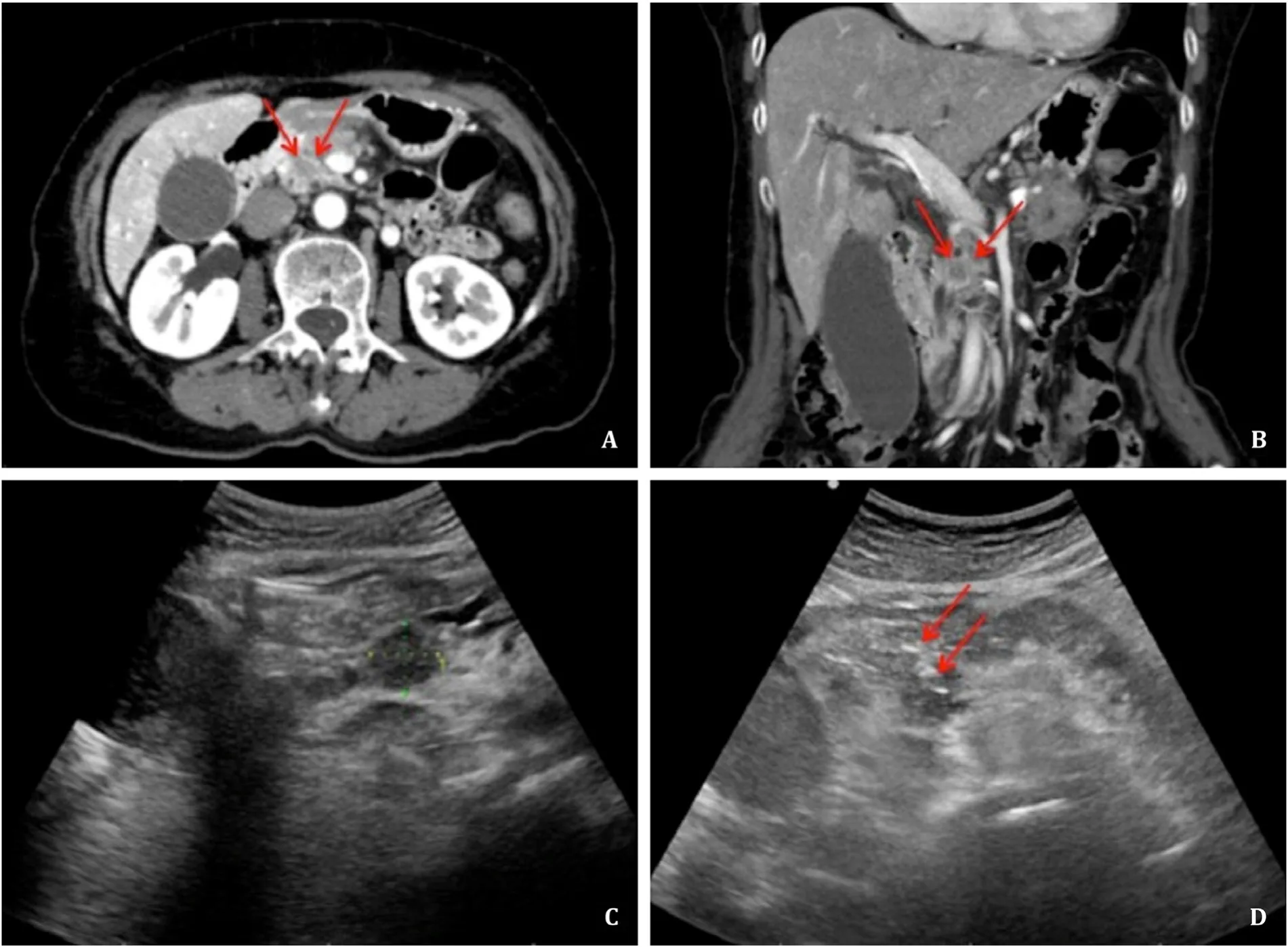

Fig. 3. A: CT suggested that a low-density lesion (red arrows) that was poorly vascularized was located in the uncinate process of the pancreas. B: Percutaneous pancreatic biopsy of the lesion would be complicated and limited under US guidance because the normal structure of the pancreas and surrounding main artery on the trans-abdominal puncture route would increase the risk for complications. C: Under the guidance of EUS, the lesion definitively presented with a maximum diameter of 2.0 cm. D: A 22G needle (red arrows) was used, and the pathological biopsy suggested that the mass was moderate to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. CT: computed tomography; US:ultrasound; EUS: endoscopic ultrasound.

Fig. 4. A, B: Sagittal and coronal CT suggested that a low-density lesion (red arrows) was located in the uncinate process of the pancreas. C: Under the guidance of US, the lesion was definitively located, with a diameter of 1.7 cm. D: Percutaneous trans-gastric CNB was performed with an 18G needle (red arrows) under the guidance of US, and the pathological biopsy suggested pancreatic adenocarcinoma. CT: computed tomography; US: ultrasound; CNB: core needle biopsy.

Biopsy of lesions in uncinate process of pancreas

A total of 224 biopsies of lesions were located in the uncinate process. The diagnostic accuracy was 84.9% in the EUS-FNA group and 93.0% in the US-CNB/FNA group (P= 0.072); the inconclusive pathological biopsy was 15.1% in the EUS-FNA group and 8.2% in the US-CNB/FNA group (P= 0.140); the repeat biopsy was 11.3% in the EUS-FNA group and 7.0% in the US-CNB/FNA group (P= 0.314).The factors of lesion size<2 cm (28.3% vs. 13.5%,P= 0.012), operator (level 3) (92.5% vs. 42.1%,P<0.001), and application of CEUS(34.0% vs. 75.4%,P<0.001) were significantly different between the EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA groups. For lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas<2 cm in size, the differences in the rates of inconclusive pathological biopsy, inaccurate diagnosis and repeat biopsy between the EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA groups were not statistically significant; accordingly, the diagnostic accuracy was 80.0% in the EUS-FNA group and 78.3% in the USCNB/FNA group (P= 0.898). Two cases of EUS-FNA and one case of US-CNB for tumors located in the uncinate process of the pancreas are presented in Figs. 2-4 .

Discussion

Our study indicated that both US-CNB/FNA and EUS-FNA demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance in pancreatic diseases, which was similar to those in previous reports.Some scholars thought that US-guided percutaneous pancreatic biopsy should be used as the primary invasive method to reveal the underlying pathology of a solid pancreatic mass because it provides a well-preserved tissue structure for histologic evaluation [ 1 , 2 , 14-16 ]. Since US-CNB and US-FNA share very similar efficacy and safety profiles regardless of the location of the target pancreatic lesion, the choice of pancreatic biopsy technique can be made at the discretion of the operator [2] . In our center,US-CNB and US-FNA were adopted for pancreatic lesions according to the operators’ experience and the size and location of the target lesion [12] . EUS guidance has an advantage over US guidance because targeting small masses with percutaneous US is difficult and a percutaneous biopsy approach is not feasible [ 4 , 17 ]. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that EUS-FNA has become increasingly available and has a diagnostic accuracy of 79% to 98% for pancreatic masses, which is similar to US-guided percutaneous CNB or FNA. EUS-FNA is indicated by practice guidelines for unresectable solid pancreatic masses or resectable masses with atypical imaging features [ 1 , 17-19 ]. Based on our clinical experience, FNA has certain limitations. First, the tissue aspirated by FNA is usually not sufficient for routine evaluation of immunohistochemical markers and molecular testing. Second, the diagnosis of some specific diseases requires preserved architectural patterns, such as subepithelial and intramural lesions, lymphomas,well-differentiated adenocarcinomas, autoimmune pancreatitis,highly desmoplastic pancreatic neoplasms, and pancreatic adenocarcinomas surrounded by chronic pancreatitis [3] . Therefore,to overcome the limitations of both EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA, a tailored approach that considers the indications for biopsy, tumor loc ation and further management possibilities seems desirable.

In our study, a tailored selection between EUS-FNA and USCNB/FNA was routinely adopted for various solid pancreatic masses. Both the major complication rates of EUS-FNA (0.4%) and US-CNB/FNA (0.8%) were low and the difference between the two groups was not significant. Smaller lesions with size<2 cm were more likely to be biopsied with the EUS approach, and the rate of PDAC was lower in the EUS-FNA group than in the US-CNB/FNA group, which may be due to the improved diagnostic efficacy of EUS for complicated pancreatic disease. However, inconclusive pathological biopsy, inaccurate diagnosis and repeat biopsy were more common in the EUS-FNA group than in the US-CNB/FNA group.

Factors influencing the incidence of inconclusive pathological biopsy and inaccurate diagnosis were explored in our study. According to multivariate analysis, pancreatic lesions with a size<2 cm, a hypoechoic appearance, a non-PDAC diagnosis, biopsies performed under EUS guidance were associated with inconclusive pathological biopsy. Hypoechoic lesions, lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas and biopsies performed under EUS guidance were factors for inaccurate diagnosis. A previous study also suggested that lesion size and location affected the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA. The decision to perform percutaneous core biopsy or FNA should also be dependent upon size and lesion location [12] . However, a previous study considered that there were no significant differences in diagnostic performance according to lesion location or biopsy type [2] . Lesion size was reported to be an independent factor affecting diagnostic accuracy, and in our study,a lesion size<2 cm significantly influenced the diagnostic yield of pancreatic biopsy. According to the results, the diagnostic performance of EUS-FNA is inferior to that of US-CNB/FNA because the majority of small lesions were subsequently referred to EUS-FNA in case the tumor was deemed inaccessible with the percutaneous approach. Certain pancreatic tumors with atypical imaging features were finally referred to EUS to achieve better visualization and obtain an imaging-based diagnosis.

Repeat pancreatic biopsy is recommended and commonly adopted in most centers if the pathologic diagnosis is inconclusive or inconsistent with the clinical presentation. A recent metaanalysis provided high-quality evidence supporting the practice of repeat EUS-FNA for pancreatic masses after initial non-diagnostic or inconclusive biopsy results. The specificity was 98%, with a low false-positive rate, demonstrating that repeat EUS-FNA substantially increased the diagnostic yield [20] . According to the multivariate analysis, hypoechoic lesions, lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas and non-PDAC diagnosis were factors for repeat biopsy. In the 41 patients who underwent repeat pancreatic biopsy under either US or EUS guidance, apart from inconclusive pathological biopsy, inflammation was the second reason for repeat biopsy, which included autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) and chronic pancreatitis. Eight cases of inflammation were reconfirmed by repeat biopsy, and 2 cases of inflammation on the first biopsy were finally demonstrated to be PDAC by repeat biopsy.

Since lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas was a risk factor for both repeat biopsy and inaccurate diagnosis,we focused on the application of pancreatic biopsy for lesions in the uncinate process of the pancreas. In our practice, the diagnostic accuracies of EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA for lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas were not significantly different; however, the differences in size<2 cm, operator (level 3) and application of CEUS were statistically significant. Due to technique limitations, EUS-FNA was almost always performed by experienced operators with at least 10 years of endoscopy experience, and CEEUS, which serves as an important method for evaluating the inner vascularization of the tumor and distinguishing necrosis from solid elements, has not been regularly used in the past few years. The uncinate process is relatively distant from the pancreatic and common bile ducts, but it is closer to the superior mesenteric artery,superior mesenteric vein and main portal vein than the remaining pancreas. Small lesions in the uncinate process were poorly visualized on US and were more difficult to puncture with a safe transabdominal approach [21-23] . According to our results and clinical experience, we preferred EUS-FNA over US-CNB/FNA for lesions located in the uncinate process of the pancreas with a size<2 cm,even though the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA was demonstrated to be equal for these lesions. Visualization from the duodenum to the uncinate process of the pancreas was more direct and safer because the main vessels and structure could be avoided, and the puncture method was relatively short and safe.

Our study had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study with some confounding factors that were beyond our control. Second, the enrolled patients were not randomized into the two groups and instead were stratified based on operator preference and experience. A large-scale, multicentre, prospective study is warranted to validate the findings of our study, especially for EUS-FNA of pancreatic lesions located in the uncinate process with a size<2 cm. In our study, the size of the needle used in EUS-FNA and US-CNB/FNA was significantly different. We did not investigate whether this factor influenced the outcomes of pancreatic biopsy.In the future, we would like to investigate whether the size of the needle is associated with diagnostic performance under the same biopsy technique. Finally, as the novel needles specifically designed to obtain histological specimens have become available from EUS approach, the limitation of EUS-FNA could be overcome by the obtainment of a tissue core for histologic examination by EUS-fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB). Previous studies found that the diagnostic performance of EUS-FNB for both pancreatic and non-pancreatic lesions was extremely encouraging [24-26] . In this study, EUS-FNB was not applied because the novel needles were not available in our center. The comparison of EUS-FNB and other traditional techniques of pancreatic biopsy should be investigated in the near future.

In conclusion, both percutaneous US- and EUS-guided biopsies of solid pancreatic lesions are safe and effective; though the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA is inferior to US-CNB/FNA.A tailored pancreatic biopsy should be considered a part of the management algorithm for the diagnosis of solid pancreatic disease.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediTauthorshipcontributionstatement

Wei-LuChai:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.Xiu-FengKuang:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft.LiYu:Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing -original draft.ChaoCheng:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Xin-YanJin:Methodology, Writing - original draft.Qi-YuZhao:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.Tian-AnJiang:Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from The Development Project of National Major Scientific Research Instrument (82027803), National Natural Science Foundation of China(81971623) and Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ20H180 0 01).

Ethicalapproval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of medicine (2021-455).

Competinginterest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年3期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2023年3期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Narrative medicine principles and organ donation communications

- Hepatobiliary&Pancreatic Diseases International

- Laparoscopic extended right hepatectomy for posterior and completely caudate massive liver tumor (with videos)

- Etiology and classification of acute pancreatitis in children admitted to ICU using the Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (pSOFA)score

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: What impacts treatment duration?

- Increased incidence of indeterminate pancreatic cysts and changes of management pattern: Evidence from nationwide data