Current and recent cigarette smoking in relation to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in an elderly male Chinese population

Wen-Yuan-Yue WANG ,Xiao-Fei YE ,Chao-Ying MIAO ,Wei ZHANG ,Chang-Sheng SHENG ,Qi-Fang HUANG ,Ji-Guang WANG,,?

1.School of Public Health,Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine,Shanghai,China;2.Department of Cardiovascular Medicine,The Shanghai Institute of Hypertension,Ruijin Hospital,Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine,Shanghai,China

ABSTRACT OBJECTIVE To investigate the association between current and former smoking and the risk of mortality in elderly Chinese men.METHODS Our study participants were elderly (≥ 60 years) men recruited in a suburban town of Shanghai.Cigarette smoking status was categorized as never smoking,remote (cessation > 5 years) and recent former smoking (cessation ≤ 5 years),and light-tomoderate (≤ 20 cigarettes/day) and heavy current smoking (> 20 cigarettes/day).Cox proportional hazards models and restricted cubic splines were used to examine the associations of interest.RESULTS The 1568 participants had a mean age of 68.6 ± 7.1 years.Of all participants,311 were never smokers,201 were remote former smokers,133 were recent former smokers,783 were light-to-moderate current smokers and 140 were heavy current smokers.During a median follow-up of 7.9 years,all-cause,cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular deaths occurred in 267,106 and 161 participants,respectively.Heavy current smokers had the highest risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality,with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 2.30 (95% CI: 1.34-4.07) and 3.98 (95% CI: 2.03-7.83) versus never smokers,respectively.Recent former smokers also had a higher risk of all-cause (HR=1.62,95% CI: 1.04-2.52) and non-cardiovascular mortality (HR=2.40,95% CI: 1.32-4.37) than never smokers.Cox regression restricted cubic spline models showed the highest risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality within 5 years of smoking cessation and decline thereafter.Further subgroup analyses showed interaction between smoking status and pulse rate (≥ 70 beats/min vs.< 70 beats/min) in relation to the risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality,with a higher risk in current versus never smokers in those participants with a pulse rate below 70 beats/min.CONCLUSIONS Cigarette smoking in elderly Chinese confers significant risks of mortality,especially when recent former smoking is considered together with current smoking.

Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking has substantially decreased in the past several decades in Western countries,it is still very high in China,especially in men.[1,2]According to 2018 China Adult Tobacco Survey in 19,376 Chinese participants,the prevalence of daily cigarette smoking was 44.4% in men (n=9109) and 1.6% in women (n=10,267),with an overall prevalence of 23.2% in men and women combined.[2]In Chinese men,the prevalence of daily cigarette smoking increased from 26.7% at age 15 to 24 years (n=930),to 45.5% at age 25 to 44 years (n=5128),and to 52.2% at age 45 to 64 years (n=8652) and then decreased to 39.8% at age 65 years and over (n=4666).In addition,in male daily smokers,the prevalence of heavy current smoking (≥ 20 cigarettes/day) was 56.4%.[2]

One of the most often seen reasons for smoking cessation is health concerns with an established severe disease,such as cancer or cardiac attacks.[2-5]Smoking cessation,sooner or later,is good and should always be encouraged.However,sooner is better than later.Sooner means less serious health concerns and long-term potential benefits of smoking cessation.In former smokers,recent and remote smoking may have entirely different health outcomes.[6-8]

The issue of previous smoking might be of typical clinical relevance for the prevention of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular deaths related to cigarette smoking in elderly Chinese,because there is a large number of former smokers in China and they may still have elevated risks of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality.[5,9,10]In the present study,we investigated the health consequences of current and former smoking with regard to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality in an elderly male Chinese population,with the focus on recent and remote previous smoking.

METHODS

Study Population

Our study was conducted in the framework of the Chronic Disease Detection and Management in the Elderly(≥ 60 years of age) Programme supported by the municipal government of Shanghai,as described previously.[11-15]In a newly urbanized suburban town 30 kilometres from the city centre,we invited all residents of at least 60 years of age to participate in comprehensive examinations of cardiovascular disease and risk.The Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital,Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine,Shanghai,China approved the study protocol.All subjects provided written informed consent.

A total of 3997 subjects (participation rate: 90%) were enrolled in the period from 2006 to 2011 and followed up for vital status and cause of death till June 2015.We excluded 2212 women because of the low smoking rate(2.8%,n=63;including 51 current smokers and 12 former smokers),and 217 men because the information on smoking status was not recorded.Thus,the number of participants included in the present analysis was 1568.

Cigarette Smoking

A physician administered a standardized questionnaire to collect information on medical history,smoking habits,alcohol consumption and the use of medications.Self-reported smoking habits at baseline were used to categorize participants as current,former and non-smokers.Former smokers were further divided into remote(cessation > 5 years) and recent smokers (cessation ≤ 5 years) according to the number of quitting smoking years,similarly as in a recent study in elderly Chinese.[16]Current smokers were further divided into light-to-moderate (≤ 20 cigarettes/day) and heavy smokers (> 20 cigarettes/day) according to the average number of cigarettes smoked per day.[17]

Follow-up

Information on vital status and the cause of death was obtained from the official death certificate,with further confirmation by the local Community Health Centre and family members of the deceased people.The International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9) was used to classify the cause of death.Cardiovascular mortality included deaths attributable to stroke,myocardial infarction,and other cardiovascular diseases (ICD-9,390.0-459.9).Deaths other than cardiovascular reasons were considered as non-cardiovascular mortality.

Other Data Collections

One experienced physician measured each participant’s blood pressure three times consecutively using a validated Omron 7051 oscillometric blood pressure monitor (Omron Healthcare,Kyoto,Japan) after the participants had rested for at least 5 min in the sitting position.These three blood pressure readings were averaged for analysis.Hypertension was defined as a sitting blood pressure of at least 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic or as the use of antihypertensive drugs.

A trained technician performed anthropometric measurements,including body height and body weight.Body mass index was calculated as the body weight in kilograms divided by the body height in meters squared.Venous blood samples were drawn after overnight fasting for the measurement of plasma glucose and serum total cholesterol and triglycerides.Diabetes mellitus was defined as a plasma glucose level of at least 7.0 mmol/L while fasting or 11.1 mmol/L at any time or as the use of antidiabetic agents.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software 4.2.1 (http://www.r-project.org).Means and proportions were compared by the analysis of variance and the Pearson’s chi-squared test,respectively.Continuous measurements with a skewed distribution were expressed as medians (interquartile range) and were analyzed by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test.Post hoc multiple comparison methods,including Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test,Games-Howell test,Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction were employed to further investigate the differences between various groups.The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of mortality between groups with the Kaplan-Meier survival function to show the time to death.Multiple Cox regression analysis was performed to compare hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI for the association between smoking habits and mortality.Proportional hazards assumption was checked by assessing the Schoenfeld residuals.The test for trends was performed by modeling smoking ordinal categories as a continuous variable in the Cox regression model.Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sidedP-value < 0.05.

Restricted cubic splines with 5 knots were fitted to delineate the nonlinear association of the hazard ratio of mortality with the years of smoking cessation and the average number of cigarettes smoked per day.In models with continuous years since quitting smoking (up to 61 years),current smokers were assigned a value of 0,and never smokers were assigned a value of 70,well above all former smokers.In models with continuous number of cigarettes smoked (up to 60 cigarettes/day),never smoking was assigned a value of 0 and former smoking was excluded.In both restricted cubic splines models,we designated never smokers as the reference group and assigned a mortality risk of 1 to them.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Participants

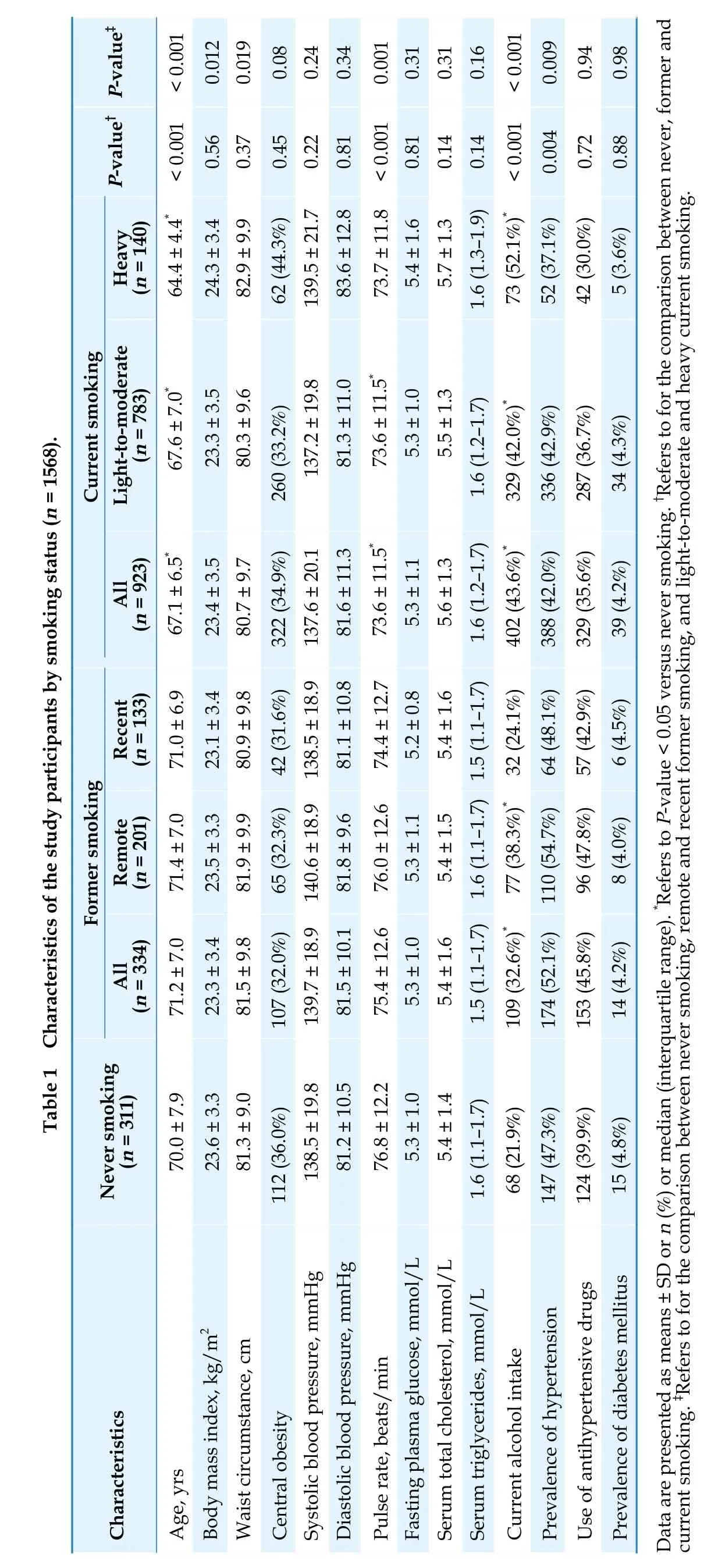

The 1568 male participants included 311 non-smokers (19.8%),201 remote former smokers (12.8%),133 recent former smokers (8.5%),783 light-to-moderate current smokers (49.9%) and 140 heavy current smokers (8.9%)(Table 1).

Overall,the mean age of the participants at baseline was 68.6 ± 7.1 years.Current smokers,compared with never smokers,were younger (-2.9 years,P< 0.001),had a higher proportion of alcohol intake (43.6%vs.21.9%,P< 0.001),and had a slower pulse rate (73.6vs.76.8 beats/min,P< 0.001).For current smokers,the median (25th-75th)number of cigarettes was 20 (10-20) per day.For former smokers,the median (25th-75th) duration of quitting smoking and age at quitting were 7.7 (2.4-15.2) years and 60(55-69) years,respectively.

Cigarette Smoking Status and Mortality

During a median follow-up of 7.9 (interquartile range: 5.5-8.9) years,the cumulated number of person-years was 10,992,and all-cause,cardiovascular and noncardiovascular deaths occurred in 267 participants,106 participants and 161 participants,respectively.The corresponding incidence rates were 24.3,9.6 and 14.6 per 1000 person-years,respectively.

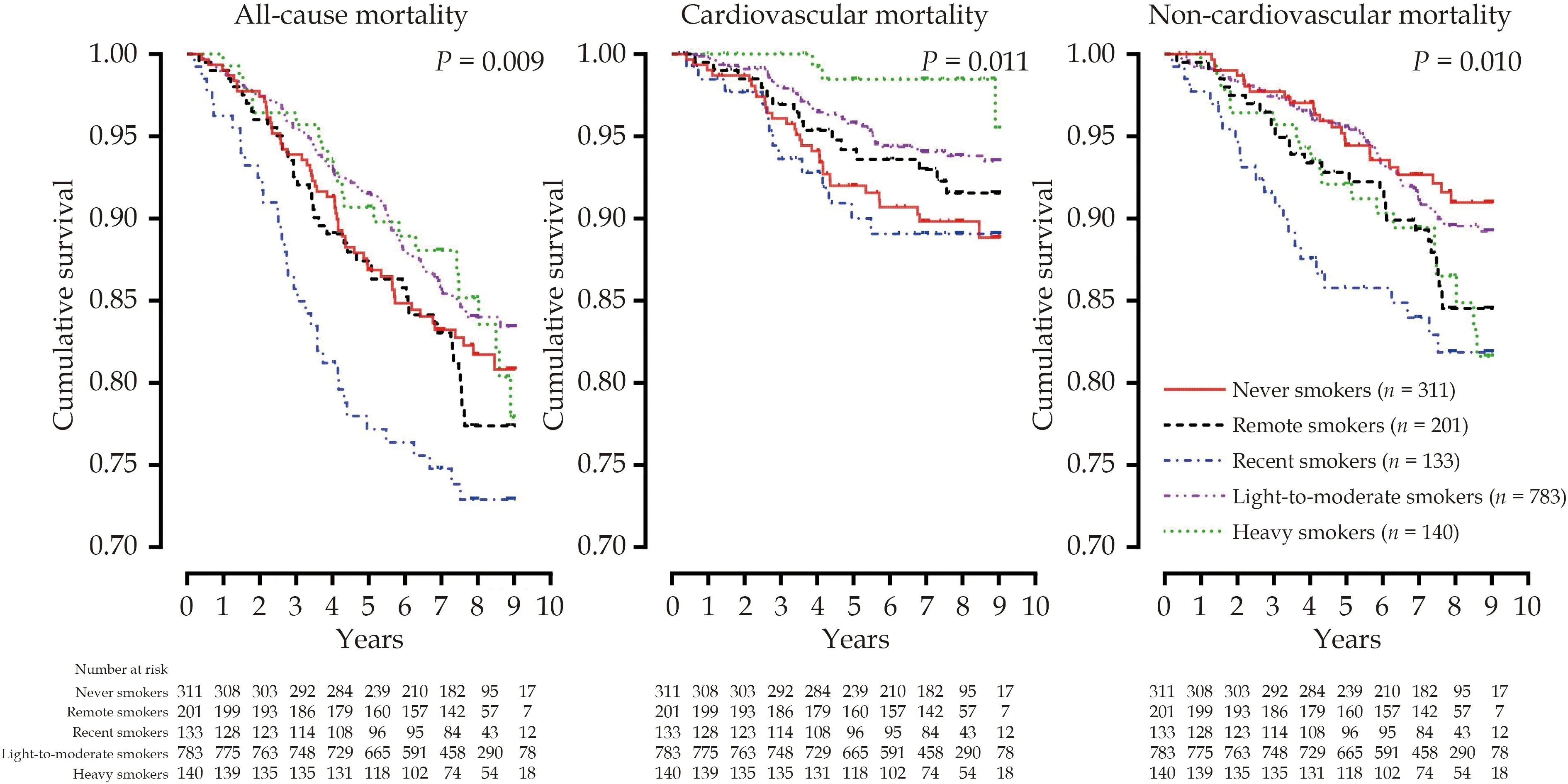

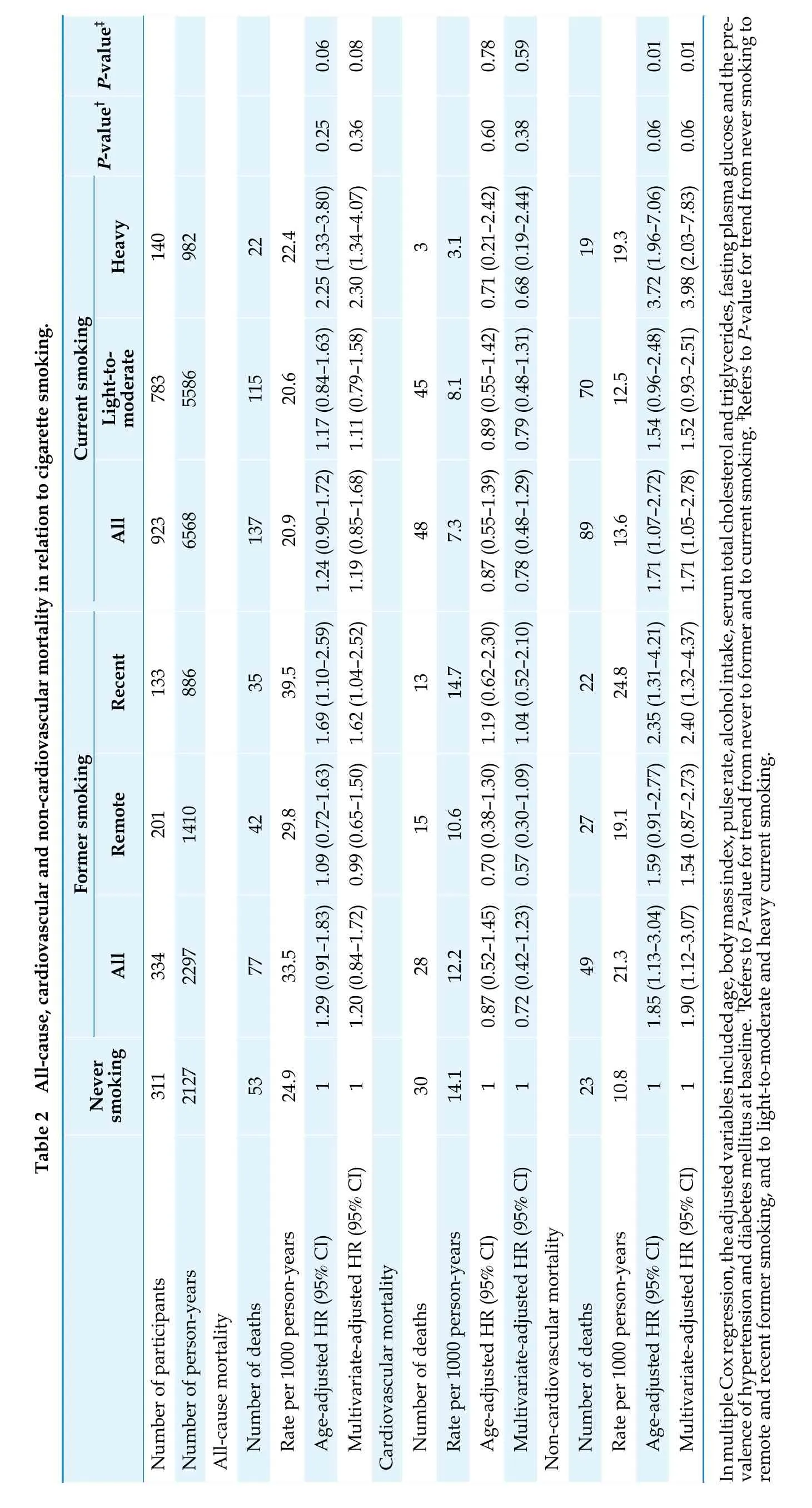

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses showed a significant difference in the incidence of all-cause,cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality between various groups according to smoking status,with the highest incidence rate in recent former smokers (log-rankP≤ 0.009)(Figure 1).After adjustment for age,body mass index,pulse rate,alcohol intake,serum total cholesterol and triglycerides,fasting plasma glucose,and the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus at baseline,both heavy current smokers and recent former smokers had a significantly higher risk of all-cause (HR=2.30,95% CI:1.34-4.07,P=0.003 and HR=1.62,95% CI: 1.04-2.52,P=0.034,respectively) and non-cardiovascular mortality (HR=3.98,95% CI: 2.03-7.83,P< 0.0001 and HR=2.40,95% CI: 1.32-4.37,P=0.004,respectively) than never smokers.However,no difference was observed for cardiovascular mortality according to the status of cigarette smoking (Table 2).

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier survival curve for all-cause,cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality of never smokers,recent and remote former smokers,and light-to-moderate and heavy current smokers. The number of participants and the P-value for log-rank test are given.

Association between the Duration of Smoking Cessation and Mortality

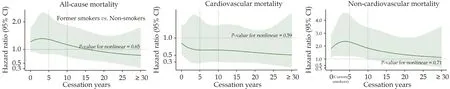

Figure 2 shows the dose-response relationship between the number of years since quitting smoking and the hazard ratio of mortality relative to never smokers.The risk of non-cardiovascular mortality peaked within 5 years of smoking cessation and started to decline thereafter.Former smokers,compared with never smokers,had non-significantly increased hazards of non-cardiovascular mortality after 10 years of smoking cessation.

Figure 2 Risk of mortality in relation to the duration of smoking cessation in former smokers with never smokers as reference by restricted cubic splines. The restricted cubic splines were adjusted for age,body mass index,pulse rate,current drinking,serum total cholesterol and triglycerides,fasting plasma glucose and the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Association between the Number of Cigarettes Smoked and Mortality

Figure 3 shows the dose-response relationship between the average daily number of cigarettes smoked in current smokers and the hazard ratio of morality relative to never smokers.The risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality increased with the number of cigarettes smoked in current smokers.

Subgroup Analyses

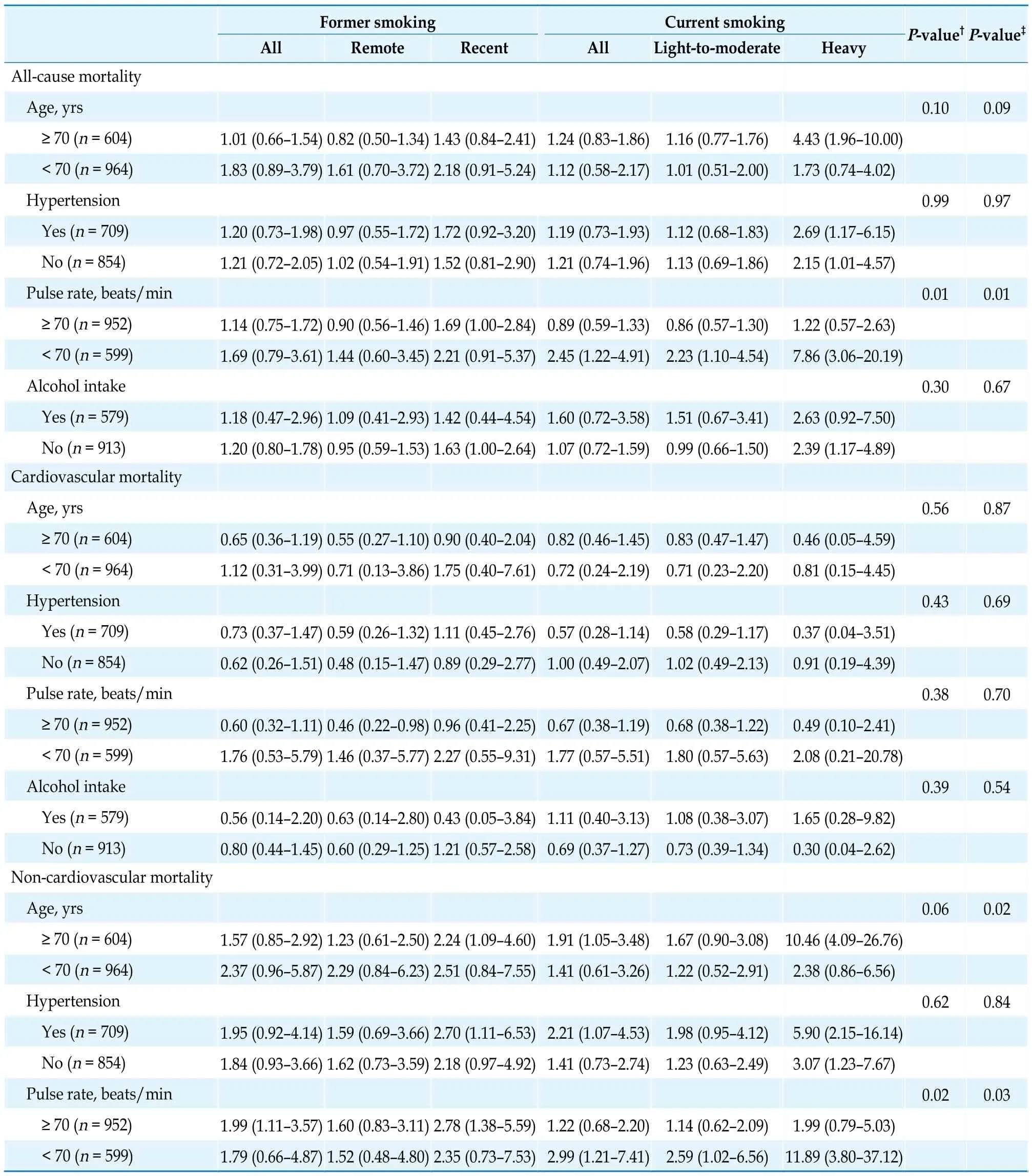

In further subgroup analyses according to age (≥ 70vs.< 70 years),the presence and absence of hypertension,pulse rate (≥ 70vs.< 70 beats/min) and alcohol intake (yesvs.no),significant interaction was observed between the cigarette smoking status and pulse rate in relation to all-cause (P=0.01) and non-cardiovascular mortality (P=0.03) (Table 3).In the study participants with a pulse rate of < 70 beats/min (n=599),but not those with a pulse rate of at least 70 beats/min (n=952),both lightto-moderate and heavy current smokers had a significantly higher risk of all-cause (HR=2.23,95% CI: 1.10-4.54,P=0.027 and HR=7.86,95% CI: 3.06-20.19,P<0.001,respectively) and non-cardiovascular mortality(HR=2.59,95% CI: 1.02-6.56,P=0.046 and HR=11.89,95% CI: 3.80-37.12,P< 0.001,respectively) than never smokers (Table 3).

Table 3 Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for the risk of mortality in remote and recent former smokers and light-to-moderate and heavy current smokers relative to never smokers according to age,hypertension,pulse rate and alcohol intake.

DISCUSSION

The key finding of our study was that heavy current smokers and recent former smokers had a higher risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality.In former smokers,the risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality was significantly elevated in recent former smoking,but started to decline after 5 years of smoking cessation,and had similar risks as never smokers after 10 years of smoking cessation.In current smokers,the risk of all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality was also higher in light-to-moderate smokers than never smokers in those with a pulse rate of < 70 beats/min.

Several previous studies showed an increased risk of all-cause mortality in older age former smokers.[16,18,19]In a large nationwide cohort study in 28,643 Chinese aged 80 years or older from 23 China provinces,both former (HR=1.18,95% CI: 1.11-1.25,P< 0.01) and current smokers(HR=1.06,95% CI: 1.02-1.10,P< 0.01) had a significantly higher risk of all-cause mortality than never smokers.However,in former smokers,the risk of all-cause mortality was much higher in transient (≤ 1 year since smoking cessation;HR=1.23,95% CI: 1.09-1.39) and recent quitters (2 to 6 years since smoking cessation;HR=1.22,95% CI: 1.12-1.32) than long-term quitters (> 6 consecutive years since smoking cessation;HR=1.11,95%CI: 1.02-1.22).[16]In a study in 160,113 Americans aged 70 years or over,recent former smokers who quitted for 1 to 4 years had the highest risk of mortality (relative risk=1.35,95% CI: 1.26-1.46,versus current smokers).[18]Taken the results of these two studies and our study together,the risk of mortality seemed to peak within approximately 5 years of smoking cessation.In addition,one study in younger elderly (aged ≥ 55 years) also showed that short-term quitters (smoking cessation ≤ 5 years) had the highest risk of mortality.[20]

Our observation on the even higher risk of mortality in recent former smokers than light-to-moderate current smokers does not at all refute the risk of cigarette smoking nor the benefit of smoking cessation.Recent former smokers might have stopped smoking because of smokingrelated illnesses,and therefore had an increased risk of mortality.Indeed,according to the 2018 China Adult Tobacco Survey,70.8% of elderly smokers had tried to quit smoking because of health concerns.[2]These recent smokers should be combined with current smokers,when the risk of cigarette smoking is considered.Otherwise,the risk of cigarette smoking would be seriously underestimated.

Our finding on the risk of heavy smoking is in keeping with the results of several previous studies.[21-23]However,the observed slower resting heart rate in current heavy smokers than other study participants is noteworthy.A previous Mendelian randomization meta-analysis supports a causal association between heavy cigarette smoking and faster resting heart rate,and suggests that the cardiovascular risk of cigarette smoking may partially operate through increasing resting heart rate.[24]Indeed,a resting heart rate of at least 80 beats/min has been considered as a cardiovascular risk factor in several recent hypertension guidelines.[25,26]We speculate that the slow heart rate in heavy smokers might have been the consequence of selective survival.Heavy smokers with a fast resting heart rate might develop diseases earlier and hence might be more likely to develop a fatal event or to quit smoking due to illness.

Several previous studies have shown a significant association between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular mortality.[27,28]Nonetheless,our observation on the stronger association of cigarette smoking with non-cardiovascular than cardiovascular mortality is in keeping with the results of previous studies in the elderly.[29-31]There is indeed a strong association between cigarette smoking and non-cardiovascular disease such as cancers and chronic respiratory diseases.[32]In China,27.8%,18.2% and 19.6% of the deaths that are attributable to smoking are cancers,respiratory diseases and cardiovascular diseases.[33]The association between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular mortality in our elderly study population might have been weakened by several important cardiovascular risk factors,such as hypertension and co-morbid cardiovascular diseases.In our elderly male Chinese population,approximately 50% had hypertension and 26% had established cardiovascular disease.[34,35]

LIMITATIONS

Our study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations.Firstly,we collected information on smoking habits at baseline but not during follow-up.It is possible that recent smokers might re-start smoking again and current smokers might quit smoking during followup.In addition,we did not collect information on the duration of cigarette smoking among smokers and the intensity of smoking among former smokers,and hence were unable to assess the health consequences of the cumulative exposure to cigarette smoking in the current and former smokers.Secondly,we did not collect information on the reasons of smoking cessation.Thirdly,we did not collect sufficient information on non-fatal cardiovascular events,such as stroke and coronary events,and had to restrict our analysis to mortality data only.The fatality rate of these cardiovascular events decreased substantially in the past few years.The mortality-restricted analysis might have underestimated the risk of fatal and non-fatal combined cardiovascular events.Finally,our study had a relatively small sample size,and hence insufficient power in the detection of significant differences for current and former smokers from never smokers.Future studies with an even larger sample size are needed.In our multiple-adjusted analysis,several variables were included in the regression model.Large number of adjusted variables might influence the test efficacy of results.However,the statistical significance and trends of the HR are largely consistent across the age-and multiple-adjusted models.The inclusion of multiple variables in the adjustment might have not compromised the validity of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Cigarette smoking in elderly Chinese confers significant risks of mortality,especially when recent former smoking is considered together with current smoking and when recent and remote former smoking are contrasted.One of the implications of our study is that stringent regulations for tobacco control are urgently needed to promote early and active smoking cessation and to improve health of the Chinese people,and smoking cessation should be as early as possible,and may achieve significant benefits even in the elderly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.91639203 &No.82070435),the Ministry of Science and Technology,Beijing,China(2018YFC1704902 &2022YFC3601302),the Shanghai Commissions of Science and Technology and Health (a special grant for “l(fā)eading academics”) (No.19DZ2340 200),the Three-year Action Program of Shanghai Municipality for Strengthening the Construction of Public Health System Big Data and Artificial Intelligence Application,Shanghai,China (GWV-10.1-XK05),and the Clinical Research Programme,Ruijin Hospital,Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine,Shanghai,China (No.2018CR010).All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose except Dr.Wang reports receiving lecture and consulting fees from Novartis,Omron,and Viatris.The authors gratefully acknowledge the voluntary participation of the study participants from Zhaoxiang Community,and the technical assistance of the physicians,nurses,technicians,and master and PhD students from Zhaoxiang Community Health Centre (Qingpu District,Shanghai) and the Shanghai Institute of Hypertension (Huangpu District,Shanghai).

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年8期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2023年8期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Prolonging dual antiplatelet therapy improves the long-term prognosis in patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing complex percutaneous coronary intervention

- Development and validation of a score predicting mortality for older patients with mitral regurgitation

- Age-related outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock stratified by etiology

- Prognostic value of hematological parameters in older adult patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary intervention: a single centre prospective study

- Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in a patient with anomalous right coronary artery originating from the left aortic sinus with interarterial course

- The first experience of multi-gripper robot assisted percutaneous coronary intervention in complex coronary lesions