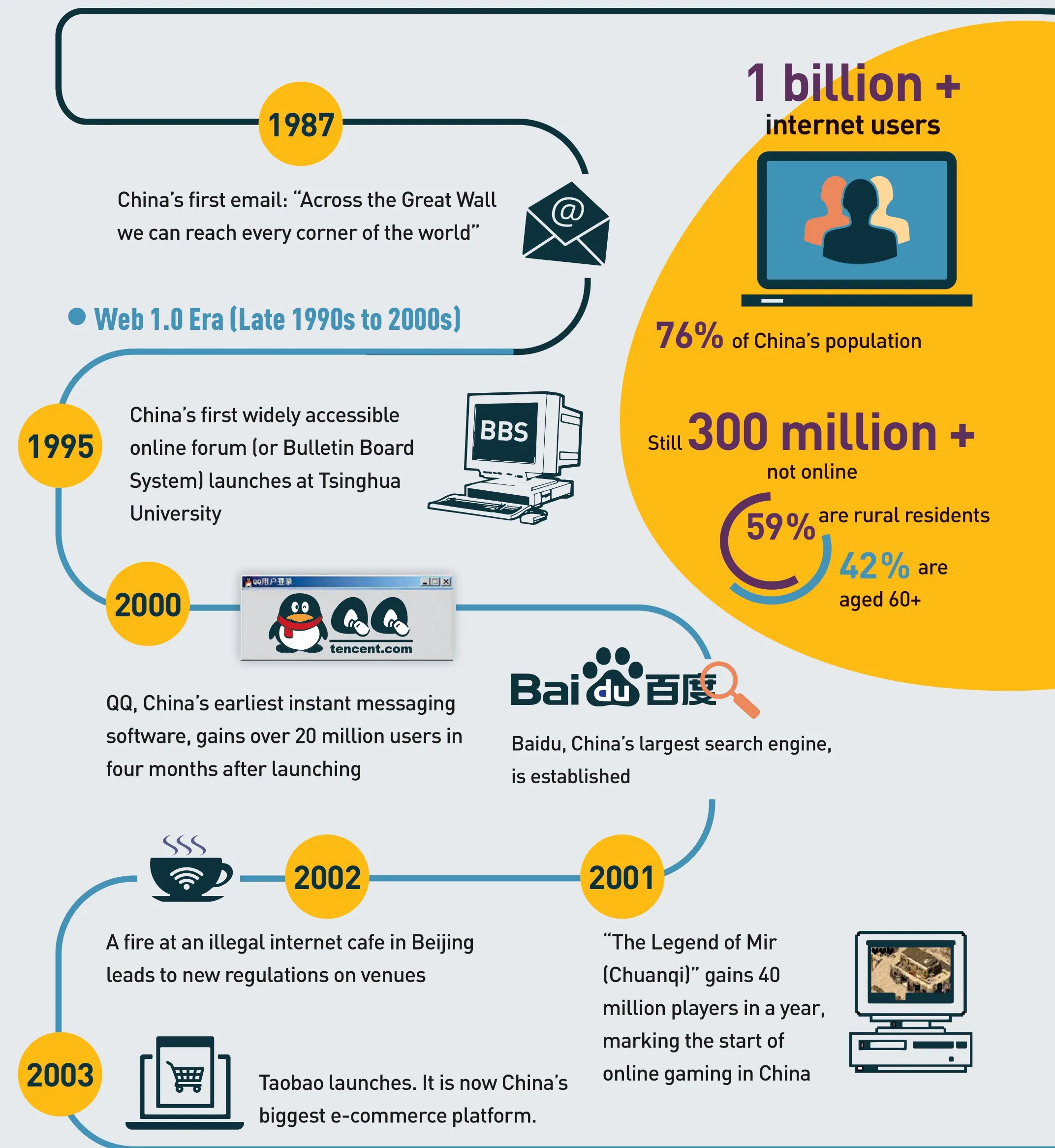

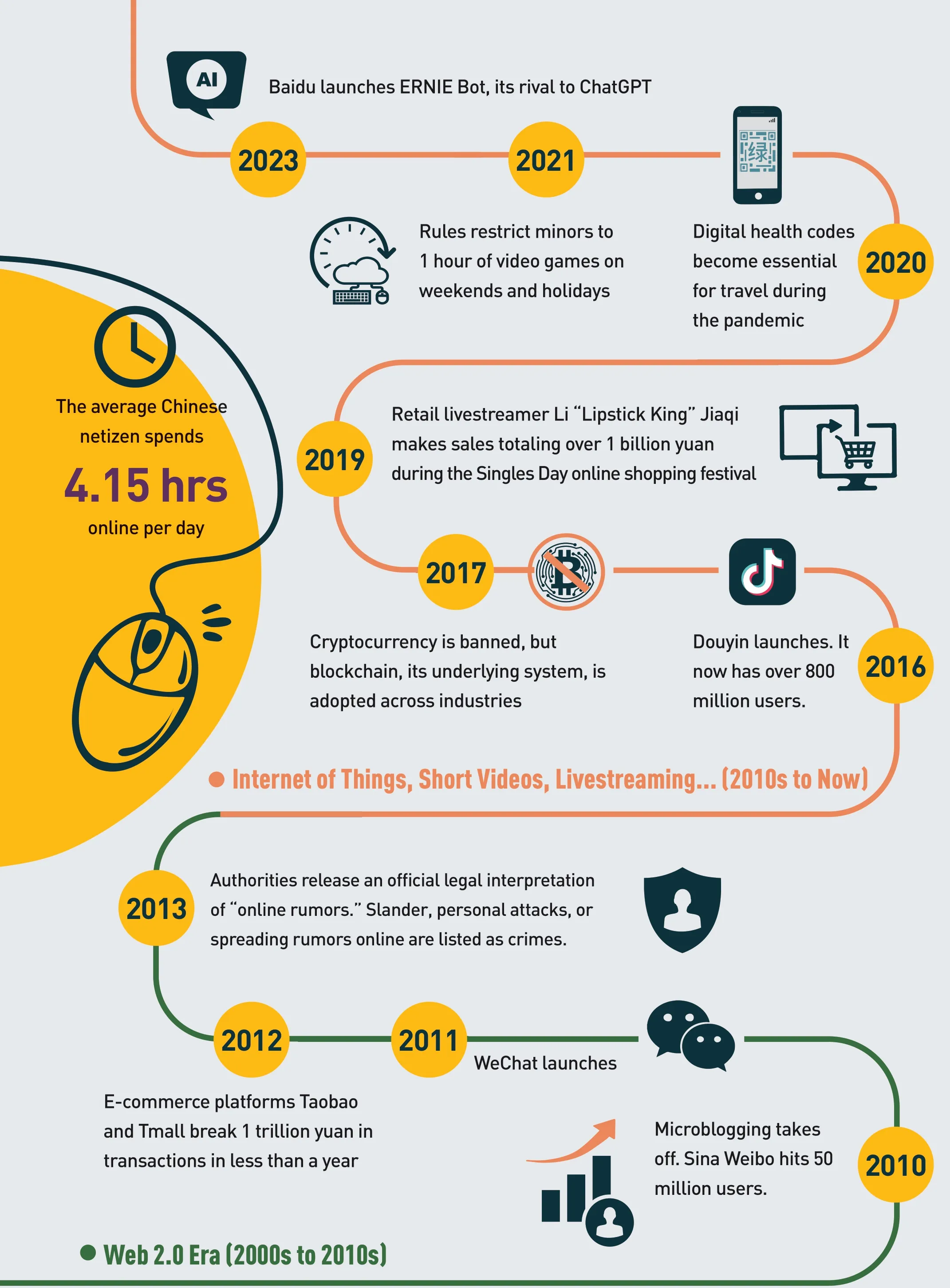

Online Odyssey

Three decades of the internet in China

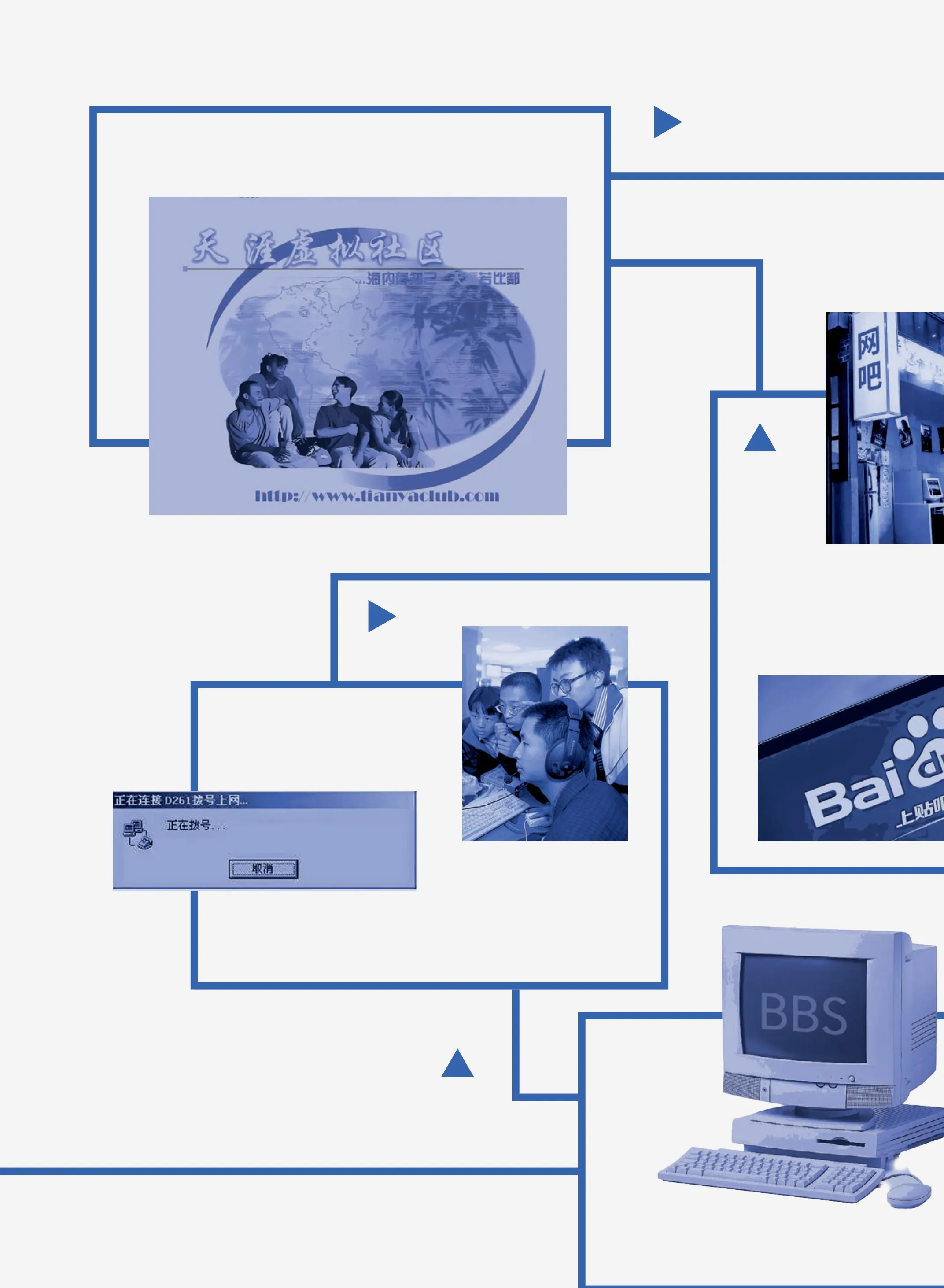

Cyber Relics

Whatever happened to China’s earIiest social media platforms?

天涯往事知多少:初代社交媒體和古早論壇文化

By Hayley Zhao

Liu Minqiao has been in a state of mourning for the past few months.Not for a lost loved one, but for the passing of a different kind of companion she’s had for two decades:Tianya, China’s earliest and once largest online forum.

After news broke of the social media platform’s official shutdown due to financial troubles on April 25, Liu, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym,quickly entered the first stage of grief—denial.“For someone like me,a Tianya veteran of 20 years, it wasn’t just a website anymore.It was like a family member to me.You can accept your parents being elderly and frail,but you can never be OK with them suddenly dropping dead, right?” says Liu, who works in the pharmaceutical industry in Canada.

Liu, who is in her 40s, is not alone in her sadness.The closure of Tianya triggered waves of nostalgia among netizens, especially those born in the 1970s and ’80s.A hashtag related to the platform’s demise swiftly garnered over 10 million views on Weibo (a social media platform that ultimately outcompeted Tianya).

This is not the first time Chinese netizens have mourned the death of a once popular social media platform,especially BBS (Bulletin Board Systems)like Tianya that hosted text-based discussion forums, and reminisced about the early years of the internet.

Maopu, an entertainment news-focused BBS platform founded in 1997 and the birthplace of multiple viral internet memes, disabled its new post function in April 2021, putting the website into eternal sleep mode.Renren Network, once popular among university students and dubbed China’s Facebook when it launched in 2005,is almost obsolete.After failing to attract users outside of college campuses, the platform was eventually sold to a technology-focused media group in 2018, becoming a relic of the past for most netizens.Baidu Tieba, which once proclaimed itself the “world’s largest Chinese online community” with over 300 million monthly active users, had lost 90 percent of them by 2021, 18 years after it was founded.Tianya’s closure is a typical tale of a platform that couldn’t keep pace with the rapidly evolving internet landscape in China.

At sky’s end

Founded on the southern island province of Hainan in 1999, Tianya, which translates to“the ends of the sky,” started as a stock market forum used by trading enthusiasts.At the time,China’s internet was populated by educated,higher-income users, and the site quickly evolved into a platform for discussing social,economic, and political topics.With the goal of becoming the “Online Sanctuary for the Global Chinese Community,” Tianya amassed 250 million monthly active users by 2019, as per its official website.

For Liu, Tianya was a window to the world beyond her hometown.Born in Hubei province,Liu was among China’s first wave of netizens after the country officially connected to the World Wide Web in 1994.She discovered Tianya in 2001 and was immediately hooked.“It was a whole new world to me.All the posts were well-written with strong opinions; I could learn something from every one of them on the site,”Liu tells TWOC.“The first batch of Chinese netizens were mostly highly educated and wellmannered, unlike now where everyone can have an opinion online.The user experience on these platforms was much better then.”

Not everyone could afford to be online in those years.A 486 personal computer, the mostadvanced model in 1995, cost over 9,000 yuan, almost double the average annual salary in China at the time.Internet cafes, orwangba(網(wǎng)吧), emerged as a popular yet still pricy alternative.The firstwangbaopened in Shanghai in 1996 and charged around 40 yuan per hour at a time when the average national monthly income was around 500 yuan.Liu remembers internet at home being charged by the minute.“To save on internet fees, I used to open a webpage, immediately disconnect the internet, read the content, and then reconnect to refresh the next page,” she says.

Tianya and Google teamed up to launch Tianya Q&A, a Quora-like platform, in August 2008 (VCG)

Still, Liu used to spend three to four hours a day on Tianya.She says the website fostered an environment of inclusivity, accommodating diverse opinions.Many published authors began their careers writing on Tianya,including Tianxia Bachang, whoseGhost Blows Out the Lightseries of novels have sold over 20 million copies worldwide and been adapted into multiple TV series and movies.Many posts on China’s stock and real estate market have proven to be prophetic.For instance, in a now inaccessible 2010 post that has since become popular online, the author predicted 13 stages of development for China’s housing market.More than half of them seem have become a reality.

But with the rise of microblogging sites like Weibo and short video platforms like Douyin(China’s version of TikTok), users’ affinity for more rigid BBS forums like Tianya has waned.“From posts to images, then to videos, and finally to livestreaming, the industry has gone through many iterations.But Tianya is still the same,” Yu, a former Tianya employee who asked to be identified by her surname, tells TWOC.Tightened regulations of cyberspace also limited discussion on certain topics that used to draw users to the platform.

“Tianya was like a whole new world to me. All the posts were well-versed with strong opinions; I could learn something from every one of them on the site.”

In 2005, Yu started her first job after college as a community operations manager at Tianya in her home province, Hainan.Her job was easy, she says, mostly managing and overseeing conversations on the forum, which left her time to learn other skills like Photoshop and coding.She was later promoted to the product management and operations team, working on projects in collaboration with Google, Tianya’s strategic partner at the time.

“Tianya laid the foundation for my understanding of community operation and provided valuable insights for my later work,”says Yu.But she left the company in 2007 and worked for other internet firms, including e-commerce giant Alibaba, before she eventually quit the industry to open her own jewelry store in 2018.Though her later jobs paid much better than the 1,200 yuan per month she received at Tianya, she still misses her time there.“[Other companies] can be very demanding.They push people to their limits.But Tianya was chill.You could do whatever you wanted and hang out with your coworkers after you clocked out,” she says.

Yu thinks this lax atmosphere probably contributed to the platform’s demise.“I had to find things to do on my own.Even my supervisor wasn’t sure what I needed to do.When I look back now, it seems that most people lacked goal-oriented management,” she says.

Yu has kept in touch with her former colleagues (through the now ubiquitous messaging, payment, and social media platform WeChat, rather than via Tianya).They had gotten wind of the company’s cash crunch before the website shut down in April.The company is 200 million yuan in debt,Tianya’s founder Xing Ming told state-owned newspaper Beijing Youth Daily in June.The Chinese technology news platform Leiphone also reported in April this year that many employees have left the company due to unpaid wages and social security contributions.Tianya had nearly 1,000 employees at its peak,but just 20 or so when it announced its closure.Attempts to raise funds to save China’s once favorite social media platform have fallen flat.After news of its closure went viral online, Tianya organized a 7-day livestream crowdfunding event on Douyin in June to raise 3 million yuan to restart the platform’s server.They made less than one-tenth of this goal.“They didn’t do a good job promoting the event.I didn’t know about it until it was over.Although Douyin is a major player in short videos, its audience doesn’t overlap much with Tianya’s,” says Liu.

Yu isn’t optimistic about the possibility of a revival.“I watched one of the livestream sessions between Xing Ming and investors.He still doesn’t have a clear vision for the site.He wants Tianya to be the largest online Chinese community in the world, but he’s not clear on what that entails,” she says.

Though Tianya’s website is inaccessible now, many remember it fondly as a place for insightful discussion.Netizens who saved or took screenshots of Tianya’s most popular posts and discussion pages are now selling them online,giving people unfamiliar with the site a glimpse into its glory days.A search on Taobao, China’s largest ecommerce platform, reveals thousands of stores selling the digital backups of those posts, with some shops boasting over 4,000 monthly unit sales.

Tieba was a chaotic ecosystem, with advertisements flooding the platform while moderators deleted posts on some heavily debated topics and even closed bars deemed controversial.

The dark web

Other early online forums, however, were less benign.Baidu Tieba, Tianya’s former competitor, is still running, but its reputation is in tatters with the platform now flooded with ads and misogynistic content.

Launched with the slogan “Born out of passion” in 2003, Tieba allows users to create online forums called “bars,” orba(吧),covering a wide range of topics from gaming to exam revision strategies.The platform also gained popularity among young people for its celebrity content.

Amber Yang, a 28-year-old warehouse manager in Guangdong province who agreed to be interviewed under a pseudonym, spent hours a day on Tieba when she first discovered the platform in 2014.She had just finished the highly stressful college entrance exam(gaokao), and suddenly found herself with a lot of free time that she filled by reading through thousands of new posts in a bar dedicated to Chinese celebrities.Occasionally she would contribute posts praising her favorite actresses or commenting on the latest celebrity fashion.“My posts used to get a lot of traffic.They often received more than 300 replies,” says Yang.

By 2015, Tieba had over 300 million monthly active users, more than Xiaohongshu, a popular Instagram-like platform launched in 2013 that had around 260 million users by the end of 2022.However, Tieba was a chaotic ecosystem, with advertisements flooding the platform while moderators deleted posts on some heavily debated topics and even closed bars deemed controversial.As it did to Tianya,Weibo stole traffic from its earlier rival, with celebrities opening their own accounts there and taking their fans with them.Yang stopped using Tieba in 2017, though the platform still had 37 million users by the end of 2021.

It’s gotten worse since.“I logged back into my old account last month just to reminisce about my college days.I found that the environment on Tieba has become very hostile, especially toward women,” she says.Many forums on the platform have become dark corners of the web.One of the most infamous is Sun Xiaochuan Bar, named after a popular video game streamer,which is rife with misogynistic content and has been dubbed the “online male public toilet”by critics.

Xiao Yi, a 22-year-old college student in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, who asked to use a pseudonym for this piece, received abusive comments on Tieba despite not being an active user.In June, Xiao posted a photo of herself in a partially torn, tight gray top, on Xiaohongshu with the caption, “The male gaze is really annoying.” In the post, she went on to complain about how some middle-aged men stared and even took photos of her and her friends when they were out shopping that day.

A day later, insults and swear words flooded the comment section under her post.Someone had taken a screenshot of her post and reposted it on Tieba.The thread there had received morethan 700 replies, most of them slut-shaming her or mocking her appearance.Some even Photoshopped her photo into explicit content.Shocked and frightened, Xiao contacted the post’s creator and the forum’s manager, urging them to remove the post and issue her an apology.She received no response for days while hundreds of abusive private messages flooded her inbox on Xiaohongshu.

Internet cafes were incredibly popular in the late 1990s and the 2000s (VCG)

One of Xiao’s followers eventually found the person who posted the photo to Tieba.Finally,after a barrage of messages from supportive(mainly female) Xiaohongshu users, the man deleted the post and reluctantly offered a halfhearted apology.He insisted that since he didn’t make the abusive comments himself, a public apology on Tieba was unnecessary.

“I was so disgusted by the whole thing, I decided to call the police,” Xiao tells TWOC.But they told her they couldn’t act without confirming the user’s real identity.They instead suggested that she file a defamation suit against Tieba to force them to provide the man’s personal information.

In July, Xiao filed a lawsuit against Tieba along with another woman who had a similar experience.A hearing could be months away and she spent over 3,000 yuan on legal fees in just one month this summer, “but I still want to go through with it,” says Xiao.“I’ve received so much kindness and support from my followers on Xiaohongshu, I want to prove to them that there are ways to fight back.” Tieba has not responded to TWOC’s request for comment at the time of writing.

Though newer social media platforms like Xiaohongshu are not perfect, they have long since left the likes of Tieba and Tianya in the past.The prospects for the revival of earlier platforms, with their stagnant interfaces and sometimes chaotic, abusive content, continue to diminish.Even Liu, still struggling to get over the end of Tianya, admits the platform failed.“Even those born in the ’90s hardly know or use the site.It failed to attract the younger generation and emerging markets,” she says.

With China now boasting over 1 billion internet users, new platforms and apps will keep emerging, vying for netizens’ increasingly short attention spans.Who knows what popular platform today will be the Tianya of the future.Perhaps in 20 years, netizens will reminisce about the joy influencers on Douyin once brought them while it lasted.

From farmers documenting rural life to travel vloggers in five-star hotels, livestreaming has become one of the most popular ways of engaging with audiences online (VCG)

Aging Influence

Seniors are increasingly online and keen to connect with new communities on social media platforms (VCG)

The suspension of a Douyin channel throws the spotlight on how online influencers attract elderly users and the risks seniors face online

短視頻的慰藉:當(dāng)老人迷上網(wǎng)紅

By Yang Tingting (楊婷婷)

Sixty-two-year-old Zhang Jian was devastated when his favorite influencer on Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) announced a hiatus from social media this August.For the past three years, watching Yixiao Qingcheng, whose name on Douyin translates to “the smile that charms a city,” had been a daily ritual for the farmer from Anhui province.“After a long day in the field, all I want to do is watch her smile while she dances and sings,” Zhang says.

After working in factories, on construction sites, and as a security guard in Shanghai, Jiangsu province, and Zhejiang province, Zhang returned home to farming this February and came across the charismatic 31-year-old social media personality.Yixiao Qingcheng, or Xiaoxiao to her fans, has amassed nearly 20 million followers on Douyin mainly by videoing herself singing and dancing.

Many of Xiaoxiao’s followers are seniors who find her presence comforting.“Xiaoxiao is a part of my life now.I tell her many things and she never gets annoyed at me,” Zhang tells TWOC, explaining that he appreciates her simple “girlnext-door” vibe.

Xiaoxiao is just one of a growing number of online influencers now popular with elderly Chinese.Armed with cellphones and often facing loneliness or boredom at home,seniors are increasingly drawn to social media personalities and livestreamers who keep them company and provide entertainment any time of day.

According to a report by the China Internet Network Information Center, nearly 300 million netizens were over the age of 50, accounting for approximately 30 percent of all internet users in China, by June 2021.China’s growing elderly population have more free time and disposable income than ever—online and offline entrepreneurs increasingly see profit in this demographic.A study by Renmin University found that, as of April 2021, users aged over 60 had created more than 600 million short videos on Douyin.

But this new trend of influencers courting the attention of seniors is also controversial.Some elderly users have blown life savings on their favorite online celebrities, while scammers have preyed on some seniors’ weak digital literacy.Other elderly folk have simply become obsessed with online personalities, even traveling hundreds of kilometers to try and meet with them.

As seniors swipe through videos, watch ones they’ re interested in, and “l(fā)ike” content, Douyin learns their preferences and provides an endless supply of similar media. Solace and companionship are just a tap away.

Many found Xiaoxiao’s hiatus from social media suspicious since it came around the same time that a similar account, named Xiucai,stopped livestreaming on August 20.Douyin later suspended Xiucai’s channel on September 2 due to alleged tax evasion.

Born in the 1980s, Xiucai had amassed over 12 million followers on Douyin, most of them middle-aged or elderly, before his account was suspended.According to Jimu News, one 62-year-old woman from Beijing sent Xiucai “virtual gifts,” a common way for livestream viewers to show their appreciation for the host, worth approximately 520,000 yuan between October and December 2020.Xiaoxiao’s followers seem even more generous.According to a report by financial news platform Xin Caijing, one Xiaoxiao fan spent at least 20 million yuan on the influencer.Many suspected that this flood of “gifting” played a role in Xiucai being reported to the authorities and Xiaoxiao going radio silent to wait out the storm.Xiucai had won his followers’ hearts with his cheeky smile, good looks, and lip-synch performances of classic songs filmed against picturesque countryside backdrops.He often encouraged his followers to “duet” with him—a function on Douyin that allows users to post their video side-by-side with a video from another creator.These duets became immensely popular, with a related hashtag gaining over 660 million views.

Liu Yinhua, a grandmother in her 60s from Hunan province, is one of Xiucai’s fans.“My sister-in-law and I made a video with Xiucai last July, and he didn’t get frustrated during the process.So later I started to watch his videos every day.For elderly people, it’s beneficial for our health to have something to do, like shooting videos, as we have a lot of free time,”says Liu, who seems unaware that the Xiucai in her duet video did not shoot the clip with her in real-time.

Liu treats the influencer as a friend, and has posted dozens of duet videos with Xiucai on her own Douyin account since July 2022.“When I’m at home with nothing to do, I just want to watch his videos,” she says.

According to Daduoduo, a data analysis platform for Douyin, over 64 percent of Xiucai’s followers are aged over 50, and over 62 percent are from less-populous “third-tier”or smaller cities.His channel had become filled with both laughter and sorrows from elderly wives at home alone, retired and bored seniors,and middle-aged divorcees.In comments on Xiucai’s videos, they would share everyday stories, from their grandchildren falling sick to their excitement about their children’s weddings.Others simply praised his talent or called him handsome.

Even though most elderly people have a poor understanding of the technology behind apps like Douyin, the simplicity of such platforms means this is no barrier to them browsing content.As seniors swipe through videos, watch ones they’re interested in, and “l(fā)ike” content,the platform learns their preferences and provides an endless supply of similar media.Solace and companionship are just a tap away.

According to a study published this August by professors He Zhiwu and Dong Hongbing of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, short video platforms like Douyin can help isolated seniors feel connected to the outside world and provide them with emotional support.Elderly women are more likely than men to browse these platforms because they spend more time at home rather than working.

Ren Xing, a music teacher in her 30s, was shocked when she discovered this summer that her technologically challenged grandmother,now in her 70s, had been following Xiucai since early 2021.But she soon understood the logic behind her grandmother’s fascination.“Most[seniors] have been trapped in a loveless marriage since they were young.They also may feel left behind by the times as they grew older.With most of them burdened by life, they tend to seek out emotional solace online.Men look for sweet girls,and women look for gentlemen,” says Ren, who agreed to be interviewed under a pseudonym.

Ren thinks Xiucai appears kind and considerate,even a bit shy at times—in contrast to her grandmother’s ill-tempered husband.“Most women weren’t treated well in the past so I can understand why middle-aged women and grandmas are drawn to [Xiucai],” she says.

An 80-year-old surnamed Hu from Jiaxing, Zhejiang province, gained popularity for livestreaming her square dancing (VCG)

Being online, however, doesn’t shield the elderly from abuse.Ren’s grandmother,who shares videos of herself dancing and singing in dresses on Douyin, sometimes receives unwanted comments from middleaged and elderly men.“Some sent my grandma messages saying things like ‘Come spend your life with me,’ making her suspicious about any male followers.She doesn’t reply to these kinds of comments anymore, because she doesn’t know if a polite ‘Thank you’ would be treated as an invitation for harassment,” says Ren.

The emotional support that elders find from influencers has also become a source of mockery among young people.Some,including elementary school students, who considered Xiucai’s performances cheesy, have started imitating the influencer and recreating his “shy and embarrassed” expressions in different scenarios, such as meeting students and their parents as Xiucai in supermarkets,or pretending to be Xiucai perusing items in a shop.Some of these spoof videos have gained over 300,000 views online.

Some even impersonate middle-aged users and leave sarcastic and sometimes explicit comments under Xiucai or Xiaoxiao’s videos.One middle-aged female netizen, using the handle Pingdan Shizhen, posted a duet video with Xiucai on Douyin, only for seemingly younger users to leave comments like “Being too lecherous can only do you harm.” The woman’s homepage now features a note: “I come from a rural village.I don’t have any other ways of entertainment.It’s only through Douyin that I get to meet you guys.Please don’t leave irresponsible comments on my channel.”

Ren believes this behavior is the result of warped societal expectations of the elderly.“Young people don’t understand why seniors express themselves so boldly, which is different from how they usually see them,”she tells TWOC.

An article by Chongqing Shangyou News in September argued that the teasing stemmed from young people not seeing the elderly as individuals with desires and emotional needs.Instead, they often view them as housewives orcaregivers who are deviating from their societal roles.For example, while it’s common for young people to become avid fans of popstars or actors and to spend money following them, when older people start to splurge on their favorite influencers, it is considered problematic.

Local authorities and social workers around the country have tried to educate seniors on how to avoid online scams (VCG)

While it’s common for young people to become avid fans of popstars or actors and to spend money following them, when older people start to splurge on their favorite influencers, it’s considered problematic.

In March last year, a woman in her 20s complained on Weibo that her mother was being unreasonable by spending money voting for her idol, 31-year-old actor Deng Lun, in competitions on the microblogging platform, and for buying an 800-yuan coffee machine endorsed by him.The woman was unhappy despite her mother spending her own money.

Some have gone to extreme lengths in pursuit of their favorite influencers.Wang Yufen, a 72-year-old retired teacher, took her fandom for Xiucai to new heights when she traveled 1,700 kilometers alone from Jilin province to Anhui this May in the hope of meeting him in person.“Why can’t someone in her 70s meet online friends?” Wang argued in a Douyin video posted by incredulous locals in Anhui after she arrived.Authorities in Anhui, normally tasked with helping homeless people, sent Wang back to Jilin at the request of her family the day after her arrival.

Many also worry that elderly social media users make easier targets for scammers.In 2020, 60-year-old Huang Yue was tricked into eloping nearly 3,000 kilometers from Ganzhou,Jiangxi province, to Changchun, Jilin province,by someone pretending to be actor Jin Dong.The online con man had claimed that he would marry her and give her 1 million yuan and a house worth 600,000 yuan.Last September,another elderly female fan of Jin Dong was scammed out of 200,000 yuan by a similar impersonator.

In both cases, a social media account purporting to be Jin Dong approached the victims through private social media messages and built an emotional rapport with them.Then, they asked for what they called investment, charitable donations, or gifts.

Yun Yi, a college student from Zhejiang province, introduced her father (who is in his 50s) to Xiaoxiao this August.He has since started watching the influencer almost every day, but Yun isn’t worried about him becoming obsessed.“Since my parents earn their own money, they have the right to decide how to spend it.Us daughters and sons need to show more support.I believe my parents will pursue celebrities rationally without it having a negative impact on our family life.”

To address the growing concerns about online fraud targeting seniors, short video platforms including Douyin declared this August that they would implement anti-scam pop-up windows,safety verifications, AI voice notifications, and daily spending limits on virtual gifts.

Zhang Jian, however, is just hoping Xiaoxiao ends her hiatus soon—he’s felt an emptiness in his life since she stopped posting videos.In the meantime, he is learning from his granddaughter how to buy and send virtual gifts on Douyin so he can shower Xiaoxiao with them if she returns.“I just want to show my support,” he says.

Digital Babysitters

The fight against ceIIphone addiction among China’s left-behind children

與電子保姆爭(zhēng)奪留守兒童的注意力

By Yang Tingting (楊婷婷)

Xia Zhuzhi only lets his 6-year-old daughter use the internet for 30 minutes a day.“Kids can’t let go of their cellphones,” says the 36-yearold associate professor from Wuhan University.“Childhood shouldn’t be about squatting in a corner scrolling through a phone all day.”

Many other parents aren’t so strict.During the Spring Festival holiday this January, Xia visited his relatives in rural Huangshi, Hubei province,but found that their pre-teen son rarely emerged from his bedroom.He was engrossed in his phone all day, and refused to even greet Xia.“That’s no childhood,” says Xia.“Childhood should be about finding playmates to have fun together, experiencing happiness and sadness together.”

Since September 2021, Xia and 149 other researchers from Wuhan University have visited nine rural counties in Henan, Hubei, and Jiangxi provinces to explore a phenomenon sweeping the countryside: cellphone addiction.

They found rural minors, especially the country’s 12 million “l(fā)eft-behind” children whose parents have moved away to work in distant cities, are spending most of their spare time indulging in short videos and mobile games without adequate supervision from their caregiver (often grandparents).

After surveying more than 1,000 households each year, the researchers found that cellphone addiction has profoundly impacted the physical and mental well-being of children, from their academic achievements to their daily lives and even family bonds.Many families and schools are at a loss with how to deal with children glued to their phone screens.

A report published this January by the China Rural Governance Research Center at Wuhan University, which Xia helped write, found that over two-thirds of 13,172 parents surveyed thought their left-behind child had a tendency toward cellphone addiction, while over a fifth reported that their children were already seriously addicted.Over 40 percent reported their child had their own cellphone, while half of them said their child used a grandparent’s device.

“There are few children playing and enjoying themselves in rural areas,” Xia tells TWOC.When Xia and his research team visited Yangxin county, Hubei province, the first children they saw were two boys and one girl, around 7 years old, all engrossed in a short-video platform on a cellphone in a hotel lobby.“Even during school breaks, classrooms and playgrounds are eerily quiet.Rather than play outside, children,especially boys aged between 8 and 14, prefer spending time watching short videos and playing video games.The social realm of rural children is swiftly shifting from nature to virtual space,”says Xia.

Li Huanhuan, a 22-year-old teacher in rural Chenzhou, Hunan province, is constantly checking whether her students have brought their phones to the classroom.All the 40-plus students (most of them left-behind children) in her middle school class have their own cellphone and WeChat account.“The boys play video games and watch short videos, while the girls take photos,” Li, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, tells TWOC.

When Li visits children at home, she finds“some students are quite introverted.They don’t know how to communicate with teachers…They don’t say anything but just bow their heads and play on their phones.” Judging by the frequency they post updates on their WeChat social feeds,some students spend all day online.

One of Li’s students even had to drop out and was sent to an internet addiction center for a year after he began spending entire days on his phone in bed.An elementary school teacher in a county in Jiangxi told Xia and his team that more than half of their students spend over 10 hours glued to their cellphones on weekends.

Elementary and middle school students are at higher risk of cellphone addiction, Xia says,because they have more free time than high schoolers who have longer school days, shorter holidays, and typically better supervision.

“Left-behind children have no one to supervise them, so they of course turn to cellphones.Once popular activities like rope skipping, playing basketball, and going fishing have all disappeared in rural areas.Now, smartphones have become everything.They’re incredibly convenient and affordable,” Xia tells TWOC.

In Xia’s own school days in the 1990s, in Huangshi he had to walk over 10 kilometers to attend classes.In that era without smartphones and computers, his spare time was filled with picking wild fruits in the mountains, climbingtrees to find bird nests, fishing in rivers, and playing with rubber bands.

Cautious and exhausted seniors often hand their “l(fā)eft-behind” grandchildren cellphones to keep them entertained (VCG)

Smartphones have become “digital babysitters”while grandparents go out to farm, work, or meet their own friends for leisure.

When Xia visited Huangshi for research in 2021, however, children told him a different story.Among the more than 30 students in one elementary school class, only one did not have their own cellphone.Some students were even aware of the problem, according to Xia: “They said, ‘What else can I do if I don’t play on my phone?’ and ‘I don’t want to be addicted, but I can’t help myself anymore.’”

The grandparents who often care for leftbehind children can be extremely cautious about the children going out to play, fearing they will get into fights, drown, play with fire, or even fall from trees.“[Grandparents and parents] are afraid that kids are not safe outside the house,”says teacher Li.“In the past, nobody cared whether kids played outside, but now they are told to go directly home after school and stay at home, where they watch TV or play on their cellphones.”

Smartphones have become “digital babysitters” while grandparents go out to farm,work, or meet their own friends for leisure.“[Grandparents] have limited energy but must look after the children’s daily needs, including food, clothing, and shelter,” Liu Qi, who has worked as a teacher in a village in Xihua county, Henan province, for over 20 years, told Southern People Weekly magazine this March.“It’s very challenging for them to handle the child’s education.When children cry or throw tantrums, they might hand them a smartphone to at least give themselves some freedom and a temporary break.”

Xia and his research team also found cellphones were blamed for the deteriorating physical health of students and an upsurge in crime.Many teachers Xia talked to attributed poor eyesight and even vision loss among students to the amount of time they spent on their phones.Additionally, Xia’s research team learned from the local law enforcement authorities in one small city in southwest Hubei,that around 70 percent of cases involving sexual assault of minors in the city during the first half of 2021 were linked to online dating or gaming.According to local officials, the number of such cases involving minors during that period surpassed the total cases reported in three years from 2017 to 2019.

Authorities have sought to address the growing addiction problem.In 2021, the Ministry of Education prohibited all elementary and middle school students nationwide from bringing cellphones into schools.If they must bring a phone, students need written permission from their parents and even then, cellphones are banned from classrooms.

In 2021, the National Radio and Television Administration restricted minors to one hour of video games on weekends.“But some children have found ways around these measures by using the ID cards and photos of their grandparents to access games or watch videos.The older generations don’t understand [what they’re being used for]…There are a lot of ways for them to play games still,” says Xia.

Rural schools also struggle to prevent students from bringing their cellphones to class.At one middle school in Yangxin, students must pass through a metal detector at the school gates.But the children devised various strategies to bypass this, such as concealing their phones in the soles of their shoes, or having others pass them phones from outside the school walls.Another secondary school in Yangxin spent over 500,000 yuan in 2020 hiring retired soldiers to patrol school grounds and confiscate phones.

A middle school student puts cellphones out of reach during class.Students are banned from bringing cellphones to school in China, except in special circumstances.(VCG)

Jin Yu, a village teacher in Shaanxi province,tells TWOC that left-behind children often persuade their grandparents to let them use their phones.“To avoid that, we tell their parents [or guardians] that we will never send homework or online courses via cellphone and ask them not to give their kids phones,” she says.“For those who still get phones, teachers will visit their homes to discuss with their guardians before collecting the cellphones, and only return them during vacation,” says Jin.

Xia agrees that the most effective approach is to keep smartphones away from children.“Instead, a simple smartwatch for communication purposes would suffice.It’s also wise not to grant children unrestricted access to the internet but rather impose limits,” he says.It isn’t always that straightforward.“Whenever I take away my granddaughter’s phone, her mother would buy her a new one,” Li Cuinian from Jiangxi told Southern People Weekly in March.Li Cuinian said her daughter-in-law has bought the child six cellphones in recent times because Li keeps confiscating them.

According to teacher Li Huanhuan, addiction drives students to extreme lengths to get their phones back.Last year, a grade nine student(who would have been 15 or 16 years old) fell on his knees in the school principal’s office, begging for him to return his confiscated phone and threatening to drown himself if he didn’t get it back.

“We can’t just ban them from using phones altogether.Lots of stuffneeds to be done online,like signing up for some exams and checking their exam feedback,” says teacher Li.“If you don’t have a phone, you need to borrow from others, but often you can only have one account[linked to one phone number],” she explains.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, schools across the country offered online classes for long periods.“Some students asked their parents to buy phones for them [to study], but after class they would just play on their phones, especially now that there are fewer online classes,” says Li Huanhuan.

This January, Xia invited several children from his village in Huangshi on a hiking trip to get them away from their cellphones.These children walked over 20,000 steps almost without a single glance at a phone screen, Xia claims.“By actively diverting their attention, we helped them develop a new habit.They realized that it wasn’t essential to constantly be on their phones.They discovered the joy of playing outside...They can now choose to use their phones or not.”

Concerned about the rising phone addiction among children in their hometown Huanggangmiao village in Hubei, retired teacher Lei Xuxin and his son Lei Yu, a journalist in his 30s, worked with the local government to establish a community center called Hope Bookhouse this March.The center is designed for students from grades two to six, providing a space where they can study,socialize, and play with volunteers.

“It’s sad for me to see these left-behind children spending entire days playing mobile games,” Lei Xuxin told state broadcaster CCTV this October, explaining his motivations.“These kids in my hometown often squat under the roofs of the homes with Wi-Fi and play on their phones.”

Located in Sanlifan town, where 90 percent of household revenue comes from people working outside, the village has 600 permanent residents,most of them elderly or children.One principal at a high school in the town told Xia that many students’ academic performance, and even their morality, were slipping due to their addiction to cellphones.The children rarely used their phones for study, according to the principal.

The Hope Bookhouse project in Huanggangmiao is based inside a renovated government building, and provided free reading, calligraphy, and chess classes, as well as significant outdoor play time, to over 40 pupils this July.The children quickly forgot about their phones when they played together, according to Xia, who participated in the establishment of the center.“The kids got familiar with each other, connected with the entire village, and finally began relishing their childhood,” he says.

Xia is planning to set up a similar center for about 40 children in Huangshi.He has already transformed two rooms of a local primary school in his hometown with books, desks,and other non-digital activities.Five teachers have signed up to entertain children during the summer vacation next July.

Xia hopes he can convince the children of the virtues of the non-digital world, get them to ditch their cellphones, and spend more time playing together like he did when he was young.“Children should be able to find the meaning of their childhood [outside],” he says.

Schools and community centers in villages sometimes offer extracurricular activities to keep “l(fā)eft-behind”children entertained during school holidays (VCG)