Music as medicine for traumatic brain injury: a perspective on future research directions

Anthony E.Kline,Eleni H.Moschonas,Corina O.Bondi

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) impacts 69 million individuals globally each year and is a leading cause of death and disability (Dewan et al.,2019).The majority of moderate-to-severe TBI survivors endure long-lasting disturbances in motor,cognitive,and affect that negatively impacts their life.Although a plethora of research on pharmacological interventions for TBI has been conducted,none has translated to the clinic,thus advocating for the evaluation of nonpharmacological therapeutic approaches that may increase translational success.

Music is well suited for facilitating recovery after TBI:Emerging evidence suggests that musicbased interventions (MBIs) hold a relatively untapped potential for improving cognition and neurobehavior after TBI.In normal uninjured rats that received MBIs,there are reports of increased hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor(BDNF) expression,reduced anxiety-like behavior,and improved cognitive benefit,which may be dependent on sex and age (Kim et al.,2006;Angelucci et al.,2007;Xiong et al.,2007;Xing et al.,2016;Papadakakis et al.,2019).Among human adults with neurological injury,MBIs improved physical and cognitive functioning,compared to those who listened to audiobooks or silence(S?rk?m? et al.,2008).Despite the encouraging findings,such studies are limited as many clinical centers do not utilize MBIs (i.e.,music medicine)because of the paucity of pre-clinical data on dose,timing,behavioral effectiveness,and safety as well as the lack of mechanistic insights.Thus,given the potential of music to provide benefits after TBI plus the need to address current uncertainties held by clinicians,additional empirical research is warranted.

We recently reported the benefits of a MBI consisting of pieces from the classical baroque period that comprises fast and slow movements and repeated motifs between solo instruments and the orchestra and simultaneous harmonies with contrasting timbre,pitch,and rhythm.The music or ambient noise began 24 hours after TBI or sham surgery and was given for 3 hours per night during the rat’s natural active state (19:00 to 22:00) for 30 days,which is when the last behavioral assessment was done (Moschonas et al.,2023).To determine the behavioral benefits of our MBI,we utilized a well-established beam-walk tasks that measured the time to traverse the beam as well as the quality of ambulation,with the latter focusing on affected hind limb foot slips.A water maze test was used to determine the acquisition of spatial learning and memory retention,while the open field test was utilized to evaluate anxietylike behavior.The shock probe defensive burying test was administered to assess passive avoidant copingvs.adaptive active coping strategies.The behavioral tests were conducted during the day so the findings could be comparable to previous intervention studies from our laboratory (Njoku et al.,2019;Gutova et al.,2021;Tapias et al.,2022).The motor and cognitive data were acquired over multiple days and therefore were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance,followed by the Newman-Keulspost-hoctest.Briefly,the results revealed that the TBI group exposed to the MBI traversed the beam significantly faster and was able to do so with significantly fewer foot slips than the TBI group that received only ambient noise (P<0.05).Similar benefits were observed for cognition as the TBI group receiving the MBI located the hidden platform quicker over timevs.the no music group (P<0.05).Additionally,analysis of the probe data,which is a measure of memory retention,revealed that the musictreated TBI group did not differ from the uninjured sham control,and both spent a greater percentage of the allotted time searching in the target zone relative to the no MBI TBI group (P<0.05).Performance in the open field test was also better in the MBI-exposed TBI rats versus those exposed to only ambient room noise.Lastly,active coping response to a stressor was eliminated by TBI as revealed by a significant decrease in time spent burying in the no music TBI group.In marked contrast,the TBI MBI group did not differ from the sham controls,which suggests an active,adaptive coping response to the stressor.

Regarding the histological and Western blot data,the MBI reduced cortical lesion volume and activated microglia as well as increased resting microglia and hippocampal BDNF expression.Taking the behavioral and histological data together,the findings of our recently published study provide a strong rationale for additional preclinical studies utilizing MBIs as a potential efficacious rehabilitative therapy for TBI.

Future research directions:While our recent findings on music as a medicine for TBI are compelling,there is much more research needed.Specifically,our study was completed in adult male rats,but questions remain regarding whether the benefits of the current MBI protocol would also be effective in adult female rats;finding the answer is necessary as females make up over 40% of the TBI population and thus determining effective treatments for them cannot be ignored.Also important is whether MBIs can impart benefits to other age groups.Preliminary data from our laboratory has shown that brain-injured pediatric rats receiving the same MBI paradigm do show benefits in the acquisition of spatial learning and memory retention,but additional data are warranted before making definitive conclusions.

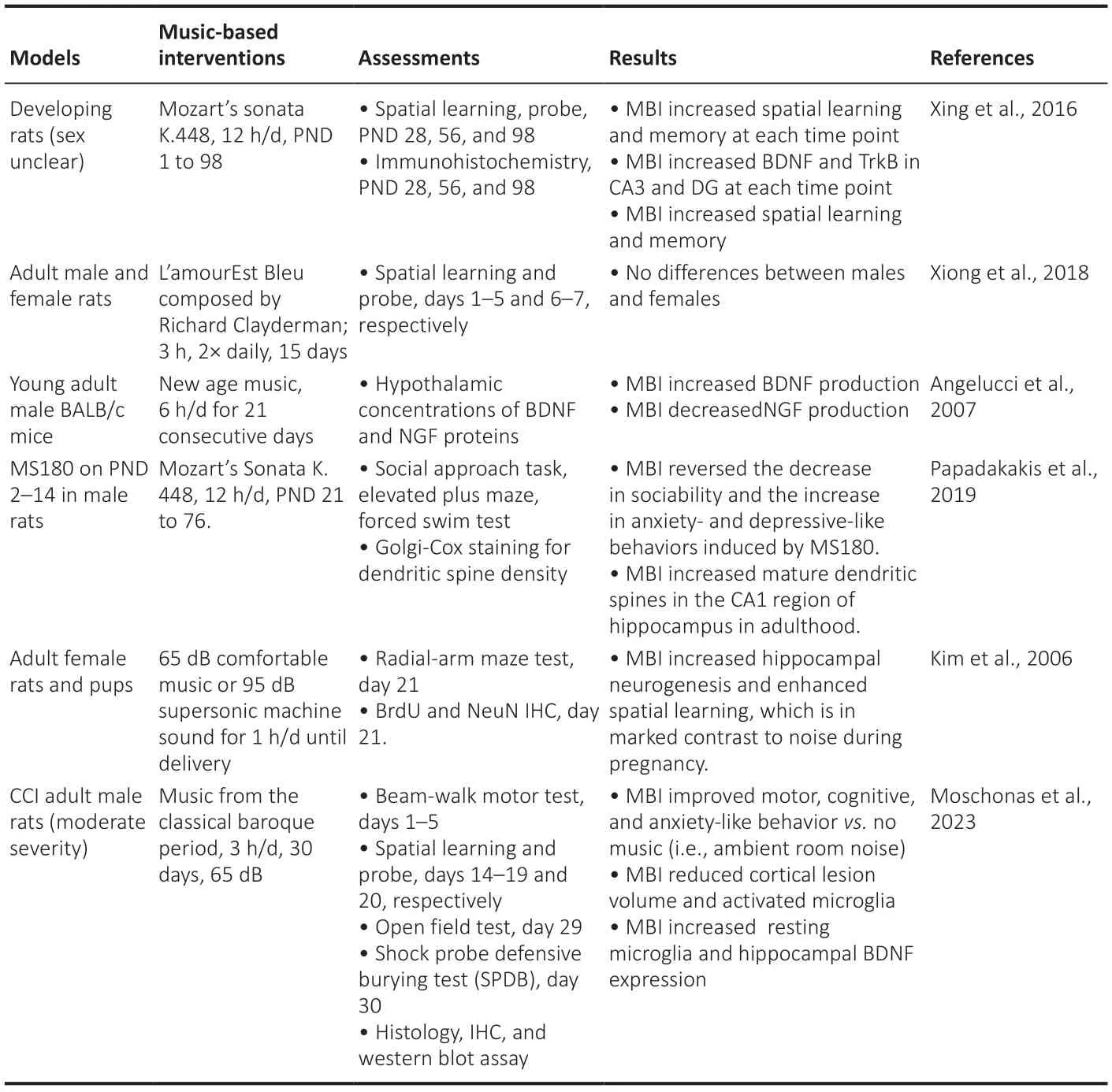

Determining other facets of MBIs is also important.For example,we utilized classical music for our study,but it is known that there are music preferences among patients and thus it is important to compare other genres of music to no music (ambient noise) for their ability to promote neurobehavioral and cognitive recovery after TBI in rats of both sexes and through the life span.We are currently evaluating different music types and comparing to classical.It is also important to determine the optimal amount of MBI to provide and at what times after TBI.We began the MBI early after TBI,as did all the other MBI studies cited (Table 1) but early times may not always be feasible due to life-saving measures taking precedence and thus the MBI will have to be delayed.Therefore,several crucial questions arise,such as will an MBI still work if presented a week or a month after TBI? Will new behavioral tests need to be utilized to evaluate the efficacy of music at later times as some behaviors may recover spontaneously? Also,important is determining potential mechanistic underpinnings.Based on the studies in non-injured rats and our recent TBI work (Table 1) there are several potential avenues to explore.

Table 1 |Summary of studies showing benefits from music-based interventions

Conclusion:The findings from our recently published manuscript evaluating the efficacy of a music-based therapy or medicine for TBI showed significant benefits in motor,cognitive,and affective outcomes as well as protection of cortical regions as evidenced by decreased lesion volumes.Increases in BDNF and resting microglia provide insight into potential mechanisms.In this perspective,we have provided additional avenues of research that could be useful in determining whether MBIs can indeed be a treatment for TBI that can successfully translate from the bench to the clinic.Future research delving deeper into MBIs after TBI will inform clinical practice in important ways.First,it will increase the understanding of how MBIs affect cognitive and neurobehavior after TBI at the biological level.Second,optimal dosing and timing schedules for improving cognitive and neurobehavioral function (i.e.,will providing different durations ortiming of initiation change the effect size) can be determined.Successful translation of MBIs may be cost-effective because it can be done in an outpatient setting and can overcome the risks and hindrances associated with drugs that often have various side effects.Lastly,MBIs can be provided across ages,genders,and cultures reflecting the diversity of TBI-survivors and importantly,signifying a widely applicable therapeutic strategy.A caveat to the previous statement is that sound sensitivity or hyperacusis does present after TBI.While the prevalence is not known,general population estimates range from 0.002% to 17%(Ren et al.,2021).As such,we acknowledge that music medicine may not be a “magic bullet” as those with extreme sound sensitivities may not be ideal candidates for treatment.However,determining the lowest decibel level that produces benefits might increase the likelihood of less extreme sound-sensitive patients also benefiting from MBIs.

This work was supported by NIH grants NS084967,NS121037(to AEK)and NS110609(to COB).

Anthony E.Kline*,Eleni H.Moschonas,Corina O.Bondi

Department of Physical Medicine &Rehabilitation,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA(Kline AE,Moschonas EH,Bondi CO)

Safar Center for Resuscitation Research,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Kline AE,Moschonas EH,Bondi CO)

Center for Neuroscience,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Kline AE,Moschonas EH,Bondi CO)

Department of Critical Care Medicine,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Kline AE)

Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Kline AE)

Department of Psychology,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Kline AE)

Department of Neurobiology,University of Pittsburgh,Pittsburgh,PA,USA (Moschonas EH,Bondi CO)

*Correspondence to:Anthony E.Kline,PhD,klinae@UPMC.EDU.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7218-3454(Anthony E.Kline)

Date of submission:October 11,2023

Date of decision:November 20,2023

Date of acceptance:December 5,2023

Date of web publication:January 8,2024

https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.392862

How to cite this article:Kline AE,Moschonas EH,Bondi CO(2024)Music as medicine for traumatic brain injury:a perspective on future research directions.Neural Regen Res 19(10):2105-2106.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal,and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License,which allows others to remix,tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially,as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2024年10期

中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)2024年10期

- 中國(guó)神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Modulation of p75 neurotrophin receptor mitigates brain damage following ischemic stroke in mice

- Conformational dynamics as an intrinsic determinant of prion protein misfolding and neurotoxicity

- Exploring the synergy of the eyebrain connection: neuromodulation approaches for neurodegenerative disorders through transcorneal electrical stimulation

- Pathogenic contribution of cholesteryl ester accumulation in the brain to neurodegenerative disorders

- Cognition and movement in neurodegenerative disorders:a dynamic duo

- Probing the endoplasmic reticulummitochondria interaction in Alzheimer’s disease: searching far and wide