Sleep quality and characteristics of older adults with acute cardiovascular disease

Haroon Munir,Michael Goldfarb

1.Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences,McGill University,Montreal,Canada;2.Division of Cardiology,Jewish General Hospital,McGill University,Montreal,Canada

Sleep plays a vital role in restoring the physical and mental health of people with cardiovascular disease.However,the hospital setting is not a conducive environment for sleep.Sleep interruptions by members of the care team,including vital sign checks,medication delivery,and blood draws for laboratory investigations,are routinely done in many hospitals.Frequent interruptions by staff and noise by other patients have been cited as barriers to restorative sleep in the hospital.[1]As a result of these sleep disturbances,nearly half of inpatients self-report poor-sleep quality while in hospital.[2]Poor sleep quality has been shown to worsen depressive symptoms of cardiovascular inpatients.A cross-sectional study of over 90 cardiac inpatients found a significant correlation between an increase in depressive symptoms and subjective sleep quality.[3]There is also evidence that sleep problems may persist in nearly half of patients following hospital discharge,which could result in longerterm adverse health consequences.[2]

Prior studies have primarily relied upon subjective sleep surveys in detailing the sleep quality and characteristics of admitted inpatients.[3]Few studies have objectively gathered data on the sleep duration and quality using validated techniques.The gold standard for objective sleep measurement is polysomnography,which captures physiological changes during sleep in measuring brain activity through electroencephalography,skeletal muscle activity through electromyography,and eye movements through electrooculography.[4]However,the use of polysomnography can be burdensome,costly,and invasive.It involves the use of a minimum of 22 wire attachments to a patient,requires observation by a trained technician,and typically requires an overnight stay in a sleep lab.[5,6]This poses limitations in the feasibility of sleep measurements in inpatients.The use of battery powered wrist worn,microprocessor powered multi-axial accelerometers with integrated validated sleep-wake detection algorithms presents a feasible,cost-effective,and less invasive option in measuring the sleep quality and characteristics of hospitalized patients.[7]Accelerometerderived data has been shown to be comparable and reliable to that obtained from polysomnography when using the validated Sadeh and Cole-Kripke sleep algorithms.[8]

There are limited data on the sleep quality and characteristics of cardiovascular inpatients using accelerometry-derived sleep data.The objective of our study was to detail the sleep quality and characteristics of older adults with acute cardiovascular disease (CVD).Data from this study can be used to inform future sleep-sensitive interventions in improving the sleep duration,quality,and overall health of patients with acute CVD.

Patients aged > 60 years of age in the acute cardiovascular units at the Jewish General Hospital,an academic tertiary care center in Montreal,Canada,who were enrolled in the Early Mobilization in Acute CVD study between April 2019 to March 2020 were eligible to participate.Exclusion criteria included a projected hospital stay ≤ 24 h or scheduled cardiac surgery.The study was approved by the institutional research ethics review board.Written informed consent was obtained for study participants.

Participants were outfitted with the ActiGraph GT9X Bluetooth Activity monitor (Actilife,Actigraph;Pensacola,Florida),a 3-axis accelerometer and inclinometer capable of providing reliable and accurate long term data discerning time spent in different mobility positions (standing,sitting,lying).[7]The ActiGraph GT9X is a small portable device outfitted on the patient’s thigh or waist,measures 3.5 ×3.5 × 1 cm and weighs 14 grams.[7]Research team members swapped devices daily,uploading data from the devices to the accompanying ActiLife software through Bluetooth technology,and sterilized devices in between patients with isopropyl alcohol.

The ActiGraph GTX9 Bluetooth Activity Monitor provides data on total sleep time,sleep efficiency,awakenings per sleep period,and the number of sleep periods during daytime hours.The device uses the validated Cole-Kripke algorithms included in the ActiLife software to determine sleep/awake status.Sleep periods are defined as the sleep episodes captured.Occurrences and duration of awakening are captured.Sleep efficiency is defined as the number of sleep minutes divided by the total number of minutes the subject was in bed during a sleep period.[9]A > 95% sleep efficiency is a considered a “good”night of sleep as validated by prior studies of adults in the outpatient setting.[10]

The primary outcome was hours of sleep per sleep period recorded.Secondary outcomes included mean sleep efficiency,mean awakenings per sleep period and Short-Form (SF) 36 scores 1-month post-hospitalization.The SF-36 a self-reported patient questionnaire consisting of physical component summary scores (PCS) and mental component summary scores(MCS),is feasibly administered in-person or through telephone,is the most widely used health-related quality of life questionnaire,and has been validated in older patient populations.[11]The SF-36 component scores are each standardized to a score of 50,with scores below and above 50 indicating below and above average outcomes respectively.Patients were contacted by telephone at 1-month to determine health-related quality of life post-hospitalization.

Data on the age,sex,length of cardiovascular ward or intensive care unit hospital stay,discharge destination and primary admission diagnosis were obtained from the electronic medical records of each subject.The primary admission diagnoses of patients were codified into the following categories:acute coronary syndromes,atrial fibrillation,congestive heart disease,and other CVD.Discharge destination was defined as either home,rehabilitation facility,or acute care facility.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ±SD,with categorial variables presented as frequencies and percentages.Between group differences were tested using the student’st-test.Bivariate Pearson’s correlation was performed to correlate sleep efficiency or duration of sleep of sleep periods with the physical component and mental component summary scores at 1-month post-hospitalization.Statistical significance was assumed using aP-value of ≤0.05.Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS 24.0 statistical software (Armonk,New York: IBM Corp.).

There were 25 patients included in the study.The mean age was 75.8 ± 7.6 years old and more than half(n=13;52%) were female (Table 1).The most common primary admission diagnoses were acute coronary syndromes (n=6;24:0%),atrial fibrillation (n=5;20%) and congestive heart failure (n=3;12%).The mean length of stay in the CICU was 4.2 ± 4.5 days and the mean length of hospital stay was 19.4 ± 20.9 days.Discharge destination was home (n=23;92%)and in-patient rehabilitation facility (n=2;8%).No patients died.There were three patients (12%) readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge.

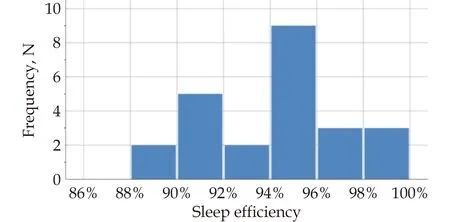

There were 93 sleep bouts with 172 sleep periods captured.One-fifth 37 (21.7%) of all sleep periods occurred during daytime hours.The mean hours of sleep per sleep period was 5.9 hours.Mean awakenings per sleep period were 4.8 with an overall mean awakening duration of 21.9 min.The mean sleep efficiency was 94.5% ± 2.9 (range 89.6%-100.0%;Figure 1).

Figure 1 Sleep efficiency percentage of patients.

MCS and PCS scores were available for 21/25(84%) of participants at 1-month follow-up.The overall mean MCS score was 30.5 ± 8.1 and the overall mean PCS score was 38.7 ± 11.2.In the univariate analysis,sleep efficiency,the number of sleep periods during daytime periods,and the number of awakenings per sleep period were not predictive of MCS or PCS at 1-month follow-up (allP> 0.05).

Our objective was to explore sleep characteristics in people admitted with acute CVD.Patients slept on average 5.9 hours per sleep period with 4.8 awakenings per sleep period and an average 20-min duration of awakening.The sleep was efficiency was overall good.The number of sleep periods during daytime and the number and duration of awakenings were not predictive of post-hospitalization health-related quality of life at 1 month.

The association between reduced sleep duration,the development of CVD,and worse cardiovascular outcomes has been previously demonstrated.The Nurses’ Health Study of 71,617 females aged 45-65 years without coronary heart disease found an increased risk of developing coronary heart disease in subjects with less than 5 hours of sleep compared to those with 8 hours of sleep.[12]A Japanese study by Liu,et al.[13]found an increased odds ratio of acute myocardial infarction in men aged 40-69 years who had fewer than 5 hours of sleep compared to those with 6-8 hours of sleep.The MORGEN study from the Netherlands reported that sleeping less than 6 hours per night was associated with a 15% increased risk of CVD.[14]Decreased sleep duration is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality in those with shorter sleep durations.[15,16]Whether reduced sleep duration during the acute phase of cardiovascular illness results in worse cardiovascular outcomes is less established.However,sleep problems experienced by many patients during their hospitalization may persist following discharge with more than half of patients reporting a reduction in sleep quality following hospitalization.[2,17,18]Our study of older adults with acute CVD found that patients slept an average of less than 6 hours per sleep period,which could potentially negatively impact in-hospital and post-discharge recovery,worsen cardiovascular disease control,and lead to increased mortality.Additional research is needed to evaluate whether improving sleep duration in older adults with acute CVD can improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Interruptions to patients while they sleep at night are common in the hospital setting.[19]A nationwide observational study surveying 39 hospitals in the Netherlands found that 70% of patients were awakened by external causes.[20]Patients were awakened on average two times throughout the night and half of these awakenings were by hospital staff members.Commonly cited sleep-disturbing factors by patients included the noise of other patients,medical devices,pain,and visits to the toilet.Patients who required diuresis and continuous intravenous drips awoke more frequently.Reducing interruptions to patient sleep could improve both duration and efficiency of sleep and improve cardiovascular health.In one study where nurses were offered sleep hygiene education,there was an increase in the total sleep time and subjective sleep quality for their patients.[2]Another study in a general medical ward where nurses were provided with education about reducing nocturnal vital sign taking and medication delivery reported a 44% reduction in nighttime room entries and increased use of sleep-friendly orders that was sustained six-months post intervention.[21]

Nocturnal interruptions and its effect on circadian rhythms within the hospital setting may worsen psychological symptoms and impair the health related quality of life of inpatients.[22,23]Sleep deprivation has been shown to increase anxiety and lead to depressive symptoms.[24-26]Up to one-half of patients with coronary artery disease have depressive symptoms and one-fifth meet the criteria for major depression,a rate that is threefold higher than the general population.[27]Patients with cardiovascular disease also have worse health-related quality of life 1-month post-hospitalization.[28]Thus,improving sleep duration and quality may be particularly beneficial for cardiovascular patients.

There are limitations to the present study.First,this was a small single-center study in an academic tertiary care hospital in Canada and its generalizability to other healthcare institutions,regions,and populations may be limited.Second,confounders of decreased sleep quality,including pre-existing diagnoses of psychiatric illness,obstructive sleep apnea,or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,were not screened for and this may have impacted participant sleep quality and duration.Lastly,concomitant delirium and the medication used to treat it was not measured in this sample population and can serve as a confounder in disrupting normal sleep-wake cycles.

Our study found that a cohort of older adults with acute CVD slept an average of about 6 hours per night with generally good sleep efficiency.There was no association between sleep duration or efficiency and health-related quality of life at one month post hospitalization.Additional studies are required to further investigate the relationship between reducing sleep disturbances and its impact on health-related quality of life of older adults with acute CVD.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None.

FUNDING

Dr.Goldfarb is supported by a Clinical Research Award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2024年3期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2024年3期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation

- Health behavior outcomes in stroke survivors prescribed wearables for atrial fibrillation detection stratified by age

- Cardiovascular risk burden and disability: findings from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS)

- Effects of loneliness and isolation on cardiovascular diseases:a two sample Mendelian Randomization Study

- Association of acute glycemic parameters at admission with cardiovascular mortality in the oldest old with acute myocardial infarction

- The diagnostic value of tenascin-C in acute aortic syndrome