Liver transplantation as an alternative for the treatment of neuroendocrine liver metastasis: Appraisal of the current evidence

Philip C.Müller,Matthias Pfister,Dilmurodjon Eshmuminov,Kuno Lehmann

Department of Surgery and Transplantation, University Hospital Zurich, R?mistrasse 100, Zurich CH-8091, Switzerland

Keywords: Liver transplantation Neuroendocrine liver metastases Liver resection Selection criteria Tumor biology

ABSTRACT Background: Liver transplantation (LT) for neuroendocrine liver metastases (NELM) is still in debate.Studies comparing LT with liver resection (LR) for NELM are scarce,as patient selection is heterogeneous and experience is limited.The goal of this review was to provide a critical analysis of the evidence on LT versus LR in the treatment of NELM.Data sources: A scoping literature search on LT and LR for NELM was performed with PubMed,including English articles up to March 2023.Results: International guidelines recommend LR for NELM in resectable,well-differentiated tumors in the absence of extrahepatic metastatic disease with superior results of LR compared to systemic or liverdirected therapies.Advanced liver surgery has extended resectability criteria whilst entailing increased perioperative risk and short disease-free survival.In highly selected patients (based on the Milan criteria)with unresectable NELM,oncologic results of LT are promising.Prognostic factors include tumor biology(G1/G2) and burden,waiting time for LT,patient age and extrahepatic spread.Based on low-level evidence,LT for low-grade NELM within the Milan criteria resulted in improved disease-free survival and overall survival compared to LR.The benefits of LT were lost in patients beyond the Milan NELM-criteria.Conclusions: With adherence to strict selection criteria especially tumor biology,LT for NELM is becoming a valuable option providing oncologic benefits compared to LR.Recent evidence suggests even stricter selection criteria with regard to tumor biology.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) represent a heterogeneous entity of neoplasms originating from cells of the neuroendocrine system [1].Most NET primaries are located within the gastro-enteropancreatic tract (GEP-NET) or the lung.Over the last four decades,NETs were increasing in incidence,up to representing the second most prevalent cancer of the digestive tract nowadays [2-4].Because of their predominantly asymptomatic appearance and slow tumor growth in well differentiated (G1/2) cases,GEP-NET are often diagnosed in advanced stages,showing synchronous metastatic disease in up to 27% [1,2].This is particularly important as the overall survival (OS) drops drastically from>30 years in localized stages to 10 years in regional disease to 12 months when distant metastases are present [2].

Evidently,stage-dependent individualized therapy remains pivotal to achieve long-term survival.Whereas radical surgical resection represents the only possible curative treatment option in localized disease [5,6],multimodal therapeutic strategies,including modern systemic and liver-directed approaches,come into play in advanced disease targeting long-term control of tumor growth and symptoms [1,7].While different systemic and interventional therapeutic regimens were recently evaluated in advanced NET,they did not show a benefit in OS [8-10].

Even though cure is rarely achieved in advanced stages and the recurrence rate is very high (up to 90%),surgical reduction of the tumor burden contributes to reasonable long-term results [11-13].With the liver being the most common and often solitary site of metastatic disease,current international guidelines recommend radical liver resection (LR) of neuroendocrine liver metastases (NELM) in resectable,well-differentiated tumors in the absence of extrahepatic metastatic disease [7,13].

Liver transplantation (LT) is a treatment option reserved to selected patients with unresectable NELM to increase surgical radicality and simultaneously minimize the recurrence rate.In fact,in patients with low-grade tumor biology,a stable disease (for around 6 months) limited to the liver with favorable long-term results has been reported [14,15].However,the role of LT in NELM is still a debated topic and adequate evidence of its role is limited [16,17],as experience in most transplant centers remains limited and despite existing guidelines patient selection is heterogeneous.

Hence,the goal of this review was to provide a critical analysis of reported data on LT and LR in NELM with a particular focus on patient selection criteria,short-and long-term postoperative outcomes,as well as potential risk factors for impaired survival.

LT for NELM

Selection criteria for LT

Candidates for LT with NELM have to be carefully selected,especially with the outlook of a limited donor pool in most countries worldwide [18].For oncologic LT indications in general,the need for lifelong immunosuppression with the risk of disease recurrence has to be carefully balanced with the benefits of patient survival.As a rule of thumb,a minimal 5-year OS of 50% should be achieved after LT to justify the use of scarce organs.

The most accepted selection criteria for patients with NELM are the 2016 revised Milan criteria [14,19],the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) [20]guidelines and the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) guidelines [21](Table 1).The UNOS guidelines are mostly based on the Milan criteria and they both advise to select patients<60 years of age with a portal drainage from the primary,less than 50% liver volume involvement and a stable disease after removing the primary for at least 6 months.Common to all selection criteria is the necessity to exclude extrahepatic disease prior to LT and selection of well-differentiated NET based on the mitotic rate or proliferative (Ki-67) index.

Table 1Selection criteria for LT candidates for NELM.

With the strict application of their selection criteria,the group from Milan reported excellent 5-year disease-free survival (DFS)and OS rates of 87% and 97%,respectively.Underlining the strict selection criteria is the fact that of 280 patients considered for LT,88 patients (31%) met the Milan-selection criteria.Due to refusal of the patients and/or medical contra-indication to LT,42 patients(15%) of this cohort were finally transplanted [14].The excellent results have thus to be interpreted in the light of this careful patient selection.Retrospectively applying the Milan criteria to a cohort from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR),the 5-year OS increased from 59% to 79%,however at the expense of excluding 64% of all patients [15].

Pre-LT diagnostics

According to the presented selection criteria for LT,accurate and high-quality imaging is of paramount importance to assess the disease burden and rule out an extrahepatic spread before LT.Metastases from NET are generally well vascularized,therefore computed tomography (CT) should always include an arterial phase.To assess the hepatic involvement in case of NELM,diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be routinely performed as it has the highest sensitivity (83%) and specificity to detect small tumors below 1 cm [22,23].Compared with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and CT in 40 patients,MRI detected significantly more metastases (n=394) than CT (n=325) or scintigraphy(n=204) [24].

Functional positron emission tomography (PET) imaging uses 68-gallium radiolabeled dodecane tetraacetic acid (DOTA) peptides in combination with CT and presents the current gold standard imaging approach especially in low-grade (G1/G2) NET.For the detection of NET,68Ga-DOTA-PET has a sensitivity of 82%-100% with a specificity of 67%-100% and it detects extrahepatic disease with a similar sensitivity and specificity [25-27].For the evaluation of LT candidates,68Ga-DOTA-PET is particularly valuable as its addition has shown to change the clinical management in around a third of patients [25].To detect intermediate or high-grade (G3) NET,FDGPET may be a valuable alternative to68Ga-DOTA-PET as it showed higher sensitivity than somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (92% vs.69%) [28].

Chromogranin A (CgA),a non-specific tumor marker was shown to correlate with treatment response of GEP-NET.CgA may be especially useful in monitoring treatment response in advanced disease after both resection and transplantation [29].However,its diagnostic value and ability to detect disease recurrence at an early stage remain controversial due to high rates of false-positive and false-negative results,and leave expert panels with a lack of consensus and no recommendation for routine use [30,31].

Outcomes

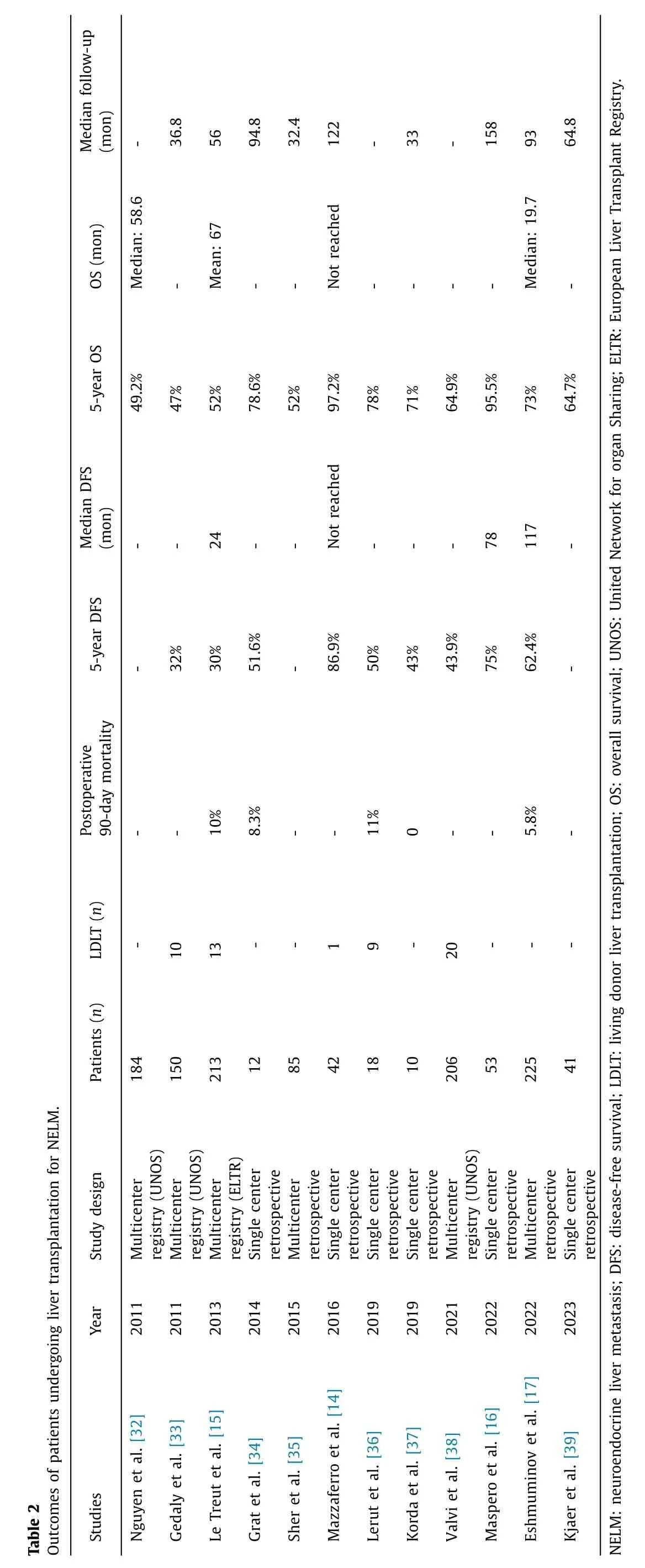

In the last decade,several studies have evaluated the outcomes of LT for NELM (Table 2) [14-17,32-39].

The reports are mainly retrospective single center analyses with small patient numbers or registry reports from the ELTR or UNOS database with a long inclusion period.Selection criteria are inhomogeneous,but impressive results were reported when adhering to the Milan criteria as mentioned before [14].Therefore,the curative role of LT seems to be an option for very well selected NELM patients,while LT beyond the Milan criteria should be very critically discussed [17].Split organs or living donor LT (LDLT) [36,38]are options to enlarge the donor pool;till now promising but limited evidence is available on respective outcomes.

In 2021,Valvi et al.published the most recent report from the UNOS dataset including 206 patients with LT for NELM.The reported 1-,5-and 10-year OS rates were 89.1%,64.9% and 46.1%,respectively.Tumor recurrence was seen in 34% with a median time to recurrence of 28 months.Recurrent rate was significantly higher in patients waiting less than 6 months for a LT compared to those waiting over 6 months (74.3% vs.25.7%) and patients younger than 45 years old had a better 5-year OS (70.9% vs.60.6%;P=0.03) [38].

The largest report from the ELTR included 213 patients from 1982-2009.The 90-day mortality rate was 10% and retransplantation rate was 11%.After a mean follow-up of 56 months,1-and 5-year DFS and OS were 65%,30% and 81%,52%,respectively.In multivariate analysis three significant factors for poor prognosis were found: major resection in addition to LT [hazard ratio (HR)=3.1],poor tumor differentiation (HR=2.7) and hepatomegaly (HR=2.3).Patient outcomes improved significantly after the year 2000 (OS: 59% vs.46%).Analyzing risk factors in the more recent patient cohort furthermore found that age>45 years(HR=2.0),hepatomegaly (HR=2.6) and resection in addition to LT (HR=1.9) were prognostic factors for poor survival [15].

These prognostic factors for oncologic long-term outcomes help clinicians to guide the selection of patients with NELM(Fig.1).First,tumor biology has to be taken into account,as poor differentiated histology (G3,Ki-67>20%) and even G2 tumors with a Ki-67 index of 10%-20% are associated with worse prognosis [14,29,37,40,41].Emphasizing the importance of tumor biology is the data from the ELTR,where 5-year OS varied greatly according to tumor grading and OS was 55% for well but only 27%for poorly differentiated NET [15].Importantly,grading can vary between the primary tumor and NELM,and treatment should be guided by the worst known grade.

Fig.1. Risk factors for impaired oncologic outcomes.

A tumor burden of over 50% liver involvement was traditionally seen as a negative prognostic factor [15,41,42],while several other studies achieved excellent results even when including patients with higher tumor involvement [14,29,40].Of note the assessment of hepatic tumor involvement is difficult in the cases of multiple metastases and its impact on outcomes remains debated [29].Another risk factor is the portal drainage of the tumor,as suggested by the Milan group [19].

However,the study by Sher et al.found similar 5-year survival for pancreatic/duodenal origin or other digestive tract (53% vs.51%;P=0.84) and the primary site of the tumor was a non-significant factor in multivariate analysis [35].

There is evidence,that extra-hepatic spread [15,29,35,40],a stable period of less than 6 months before LT [14,38,40,43]and in some series primary tumor in the pancreas [14,15,37,42]are associated with worse outcomes.

Resection for NELM

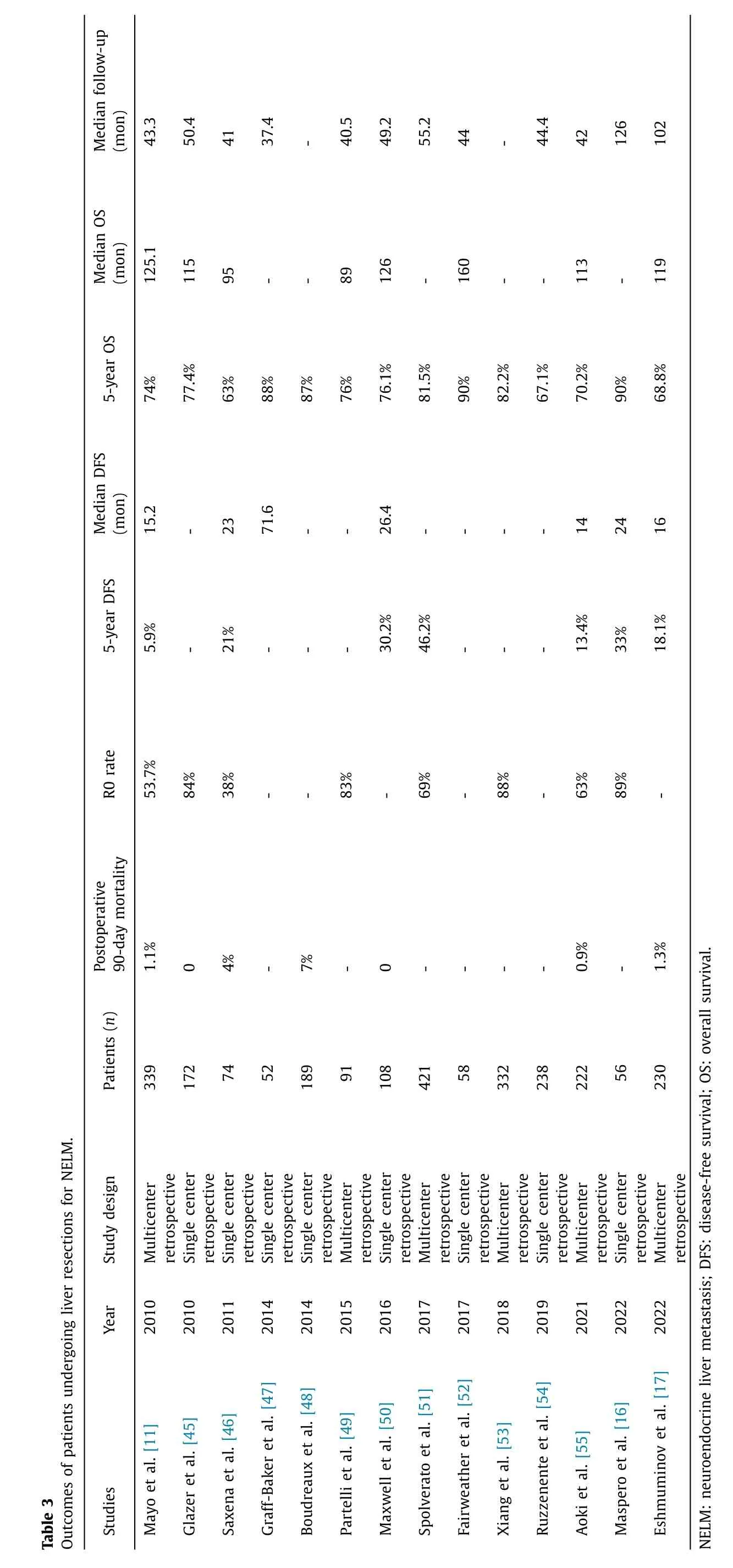

The standard approach for NELM with well differentiated histology,sufficient future liver remnant is still curative intent (R0)resection [12].Since microscopic liver disease is difficult to detect in preoperative imaging [44],a major limitation of surgical resection remains a high recurrence rate.However,excellent longterm outcomes can be obtained when an R0 resection is feasible(Table 3) [11,16,17,45-55].

A systematic review by Saxena et al.included 1469 patients from 29 case-series.A macroscopically free resection (R0/R1) was achieved in 71% while a true R0 resection was attained in 63%.The perioperative mortality ranged from 0 to 9% (median 0) with a morbidity from 3% to 45% (median 23%).The 1-,3-,and 5-year DFS and OS were 63%,32%,29% and 94%,83%,71%,respectively.The median DFS was 21 months,and the liver was the primary site of progression in 80% of patients.Factors associated with a poor prognosis were extrahepatic disease,macroscopically incomplete resection and poor histologic grading [46].

An up-to-date meta-analysis evaluating different treatments for liver metastasis (LM) from GEP-NET included 11 studies with 1108 patients.Surgical resection resulted in significantly improved OS compared to chemotherapy [odds ratio (OR)=0.05 (0.01-0.21);P<0.0001]and to embolization [OR=0.18 (0.05-0.61);P=0.006].With those clear results the authors concluded that chemotherapy and embolization should be reserved for cases when surgery is not feasible [56].

In recent years,more extensive liver surgeries such as associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy(ALPPS) [57]or classic two-staged hepatectomies [58]have been introduced to achieve a curative resection in LM formerly considered unresectable.An initial study from the international ALPPS registry included 21 patients and reported high rates of major complications (Clavien-Dindo>3a) after stage 1 (9%) and stage 2(27%) with a 90-day mortality rate of 5%.After a median follow-up of 28 months,DFS was 17.3 months with a 1-year OS of 95% [57].Based on these results,ALPPS should be included in the armamentarium in selected NELM patients,however applied with caution due to the unfavorable perioperative risk profile and short DFS.On the other hand,more favorable results have been reported for classic two-staged hepatectomies with resection of the NET primary and limited NELM resection plus portal vein ligation in a first step.After sufficient hypertrophy (around 8 weeks),major hepatectomy was performed.The French group included 41 patients and showed overall complication rates of 17% and 21% after step one and two,respectively.Perioperative mortality was 0.The reported 2-and 5-year DFS and OS were 85%,50% and 94%,94%,respectively [58].

Transplantation versus resection

There are two retrospective studies directly comparing LT with LR in NELM [16,17].Maspero et al.included 104 patients between 1984 and 2019 from a single center.All patients were within the Milan criteria and 48 underwent LT while 56 had LR.The 10-year survival rate was significantly higher in the LT group (LT: 93% vs.LR: 75%;P=0.007) after a median follow-up of 158 months for LT and 126 months for LR.Similarly,LT had a significantly higher 10-year DFS rate (LT: 52% vs.LR 18%;P <0.001).The median DFS was 78 months for the LT group vs.24 months for the LR group (P <0.001).In addition,recurrence patterns differed between the two approaches,as LR patients mainly had intrahepatic recurrence (37/42,88%),while after LT multisite recurrences were predominantly found (12/25,48%).In univariate analysis,LT was significantly associated with improved OS [HR=0.35 (0.16-0.78);P=0.010]and DFS [HR=0.36 (0.21-0.59);P <0.0001][16].

The currently largest analysis [17]included 455 patients from 15 international centers undergoing LT (n=225) and LR (n=230).The cases were collected from 1988-2021 and for the LT and LR groups a median follow-up of 93 and 102 months were available.Most of the included centers used the Milan or modified Milan criteria.In a first analysis,the authors analyzed an unmatched cohort,where DFS was significantly longer after LT than after LR [117 vs.16 months;HR=0.28 (0.21-0.36);P <0.001]and the 5-year DFS was 62.4% for the LT group and 18.1% for the LR group,respectively.Similarly,the median OS after LT was significantly longer compared to LR [197 vs.119 months;HR=0.65 (0.48-0.87);P=0.004]with a 5-year OS of 73% for LT vs.68.8% for LR (Tables 2 and 3).Adding a 1:1 propensity matched analysis based on age,tumor grade and tumor location,the oncologic benefits of LT persisted.Both DFS[107 vs.18 months;HR=0.25 (0.16-0.39);P=0.001]and OS[205 vs.120 months;HR=0.56 (0.35-0.90);P=0.015]were significantly longer after LT.In a multivariate analysis G3 grading was found as the only poor predictor of OS in resected patients[HR=2.22 (1.04-4.77);P=0.04],while in LT patients G2 grading[HR=2.52 (1.15-5.52);P=0.021]and transplantation beyond the Milan criteria [HR=2.40 (1.16-4.92);P=0.018]were associated with reduced OS.To further assess the value of tumor differentiation,the authors divided the cohort according to the Ki-67 proliferation rate.Underlining the importance of tumor biology,OS was 220 months in LT patients with a Ki-67 of less than 5% compared to 120 months in patients with Ki-67>5% (P <0.001).Looking at patient selection for LT,OS was significantly better for LT patients within the Milan criteria [LT: 320 vs.LR: 120 months;HR=0.24(0.11-0.48);P <0.001],however similar in patients beyond the Milan criteria [LT: 107 vs.LR: 111 months;HR: 0.87 (0.55-1.35);P=0.54][17].Although these two recent studies clearly show the oncologic benefits of LT in a well selected patient cohort,they also highlighted a major drawback.Available data come from retrospective data analyses,often including a major selection bias and a significant amount of missing data.In addition,long-term data are necessary in low-grade NET which often has a very slow natural evolution.The impact of novel therapies,e.g.,peptide radio receptor therapy (PRRT),remains elusive in this context.Finally,the potential benefit on long-term survival has to be carefully balanced against a higher perioperative morbidity and mortality after LT.

Conclusion

Currently,patient selection for LT of NELM should follow the Milan criteria,as the long-term benefit is lost in patients outside these selection parameters.While international consensus exists to only evaluate G1/G2 tumor histology for LT,G2 grading summarizes a heterogenous group of patients.Results from the most recent multicenter study demonstrated a distinct difference in longterm outcomes between a Ki-67 below and above 5% pointing to even stricter selecting favorable tumor biology.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Philip C Müller:Conceptualization,Data curation,Methodology,Writing -original draft.Matthias Pfister:Data curation,Methodology,Writing -original draft.Dilmurodjon Eshmuminov:Data curation,Methodology,Writing -review &editing.Kuno Lehmann:Conceptualization,Data curation,Methodology,Writing -review &editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not needed.

Competing interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2024年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2024年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Ex vivo liver resection and auto-transplantation as an alternative for the treatment of liver malignancies: Progress and challenges

- Instructions for Authors

- Liver transplantation and resection in patients with hepatocellular cancer and portal vein tumor thrombosis: Feasible and effective?

- Liver transplantation as an alternative for the treatment ofintrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Past,present,and future directions

- Liver transplantation as an alternative for the treatment of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A critical review

- Liver transplantation as an alternative for the treatment of non-resectable liver colorectal cancer: Advancing the therapeutic algorithm