桂皮醛對小鼠柯薩奇病毒誘發(fā)病毒性心肌炎的作用

丁媛媛,趙鋼濤,楊 凡,王四旺

1北京軍區(qū)總醫(yī)院藥理科,北京 100700;2第四軍醫(yī)大學(xué)藥物研究所,西安 710032

Introduction

Viralmyocarditis is amajor cause of inflammatory heart disease in Western populations.Sudden death due to viralmyocarditis is a rare event and can be studied in animalmodelsof CoxsackievirusB3(CVB3)myocarditis in which pathology is due pr imarily to viral infection. However,there is still no effective drug to treat this disease.CVB3infection is believed to be a principle trigger leading to human myocarditis[1].Following infection,cell lysis and islet degeneration occurs within 10 days,although some virus strains do establish a persistent infection in human islet cells,such infectionsin vivomight have long-ter m impacts[2].

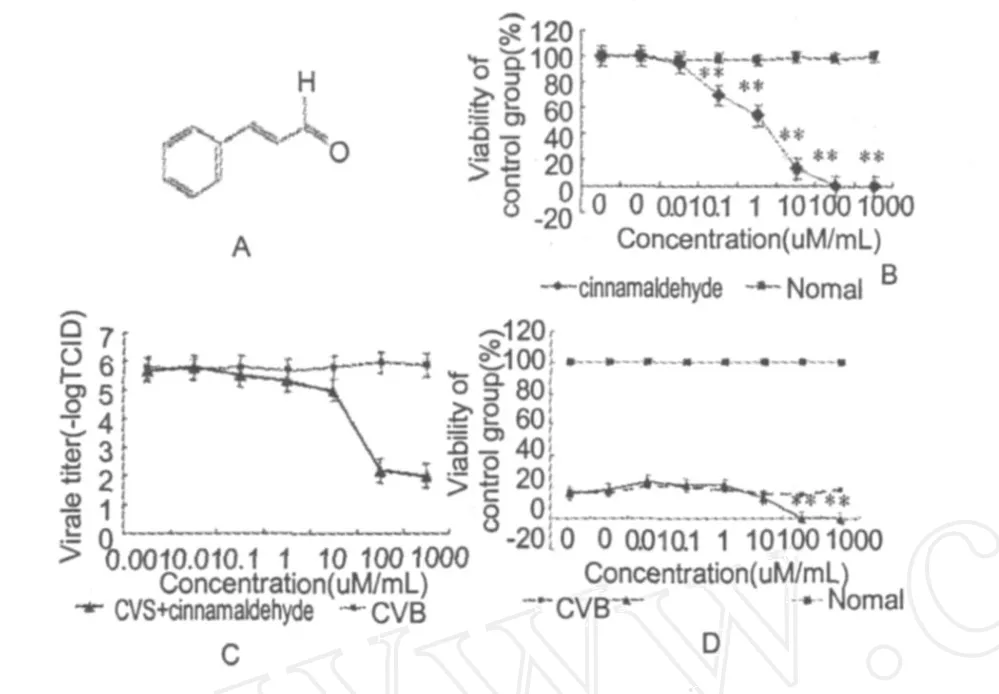

Fig.1 A:Conceptual scheme of cinnamaldehyde chem ical structure;B:Effects of cinnamaldehyde on myocardial cells viabilityin vitro;C:Effects of cinnamaldehyde on viral titers of CVB-infected myocard ial cells for 72 hours.D: Effects of cinnamaldehyde on cells viability of CVB-infected myocardial cells for 72 hours.(Data are mean ±S. D.(n=3).*P<0.05,**P<0.01,compared with CVB

Cinnamaldehyde,the main constituent of cinnamon volatile oil(>85%),isα,β-unsaturated carbonyl derivative with a mono-substituted benzene ring(Fig.1A). Cinnamaldehyde has been known to possess multiple biological activities such as peripheral vasodilatation, anti-platelet aggregation[3],anti-bacterial[4],and antiviral[5],anti-inflammation.Although cinnamaldehyde has been demonstrated to suppress the growth of influenza A/PR/8 virus,little infor mation is available regarding its effects on CVB3-induced viralmyocarditis. Recent reports have shown the ability ofNF-κB inhibitors to antagonize the development of myocarditis and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in cardiac tissues.Toll-like receptors(TLRs)have two major downstream signaling pathways,MyD88-and TR IF-dependent pathways leading to the activation ofNF-κB expression of inflammatory mediators.It has been determined that signaling factors leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines following stimulation of TLR-4 but not TLR-2 are sufficient to circumvent the protection conferred by pancreatic expression of transfor ming growth factor-β(TGF-β)from coxsackievirus-mediated autoimmune myocarditis[6].Since TLR4 and their downstream signaling components are important molecular targets for preventive and therapeutic strategy against viralmyocarditis,inhibitors of TLR4-NF-κB activation may,therefore,possess broader therapeutic actions.

Cinnamaldehyde suppressed the activation of NF-κB induced by lipopolysaccharide(LPS),a TLR4 agonist, leading to the decreased expression of target genes such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in macrophages (RAW264.7).Cinnamaldehyde did not inhibit the activation of NF-κB induced by MyD88-dependent (MyD88,IKKβ)or TR IF-dependent(TR IF)downstream signaling components.However,oligomerization of TLR4 induced byLPS was suppressed by cinnamaldehyde resulting in the downregulation of NF-κB activation.Further,cinnamaldehyde inhibited ligand-independentNF-κB activation induced by constitutively active TLR4 or wild-type TLR4[7](Younet al.2008). These results strongly implicate an immuno-modulatory role for cinnamaldehyde.None the less,the prognostic and perspective anti-viral and anti-inflammatory therapeutic relevance of cinnamaldehyde on viral myocarditis remains to be addressed.

M ethods

Reagents and chem icals

Cinnamaldehyde was provided by the China Medicine (Group)Shanghai Chemical Reagent Corporation,China.The drug was dissolved in 0.05%Tween-20 using double-distilled water.A nitrite assay kit,Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium(DMEM),and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Sijiqing Life Technologies Corporation,China.3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tertazoliumbromide(MTT),clostridiopeptid-ase I and trypase were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation(St.Louis,MO,USA).Antibodies for NF-κB,inducible nitric oxide synthase( iNOS),T LR4 and tumor necrosis factor(T NF-α)were purchased from Santa CruzBiotechnology Inc.(Santa Cruz,CA,US A).

An imals CVB3

BALB/c mice(4 weeks old,18-20 g,male),newborn Sprague-Dawley(SD)rats were purchased and maintained at the Experimental Animal Center of the Forth MilitaryMedicalUniversity.All animalprocedures used in this studywere in compliance with the criteria in the Guide for the Care and Use ofLaboratoryAnimals,prepared by the NationalAcademy of Sciences.

Virus and cell culture

HeLa cellswere supplied by the Biological Technology Center of the Forth Military Medical University and were cultured in DMEM supplanted with 10%fetal bovine serum.Primary culturedmyocardial cellswere prepared from hearts of one-day-old neonatal SD rats,following disaggregation into individual cellswith sequential digestswith trypsin and clostridiopeptidase I.Myocardial cells were cultured in DMEM supplanted with 20%fetal bovine serum.All cellswere grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5%CO2.CVB3,a gift from theMicrobiology Depar tment at the Forth Military MedicalUniversity,was propagated in HeLa cellmonolayers and stored in a small tube at-70°C.Viral titers were deter mined to be 1×105TC ID50/mL.

In vitroexper iments

Cytotoxicity assays

To establish the maximal non-cytotoxic dose of chemicals on a myocardial cell,primary cultured myocardial cells(1 ×105cells/well)were cultured in two 24-well plates,each well having a final volume of 2 ml containing 20% fetal bovine serum.Myocardial cells were exposed to cinnamaldehyde at 0,0.001,0.01 0.1,1,10,100,and 1000μM for 72 hours,after this cell viabilitywas determined.TheMTT reduction assay was used to assess cell viability.Briefly,the plateswere read on a microplate reader(Dynatech Microelisa Reader,VA,USA)at 570 nm.The cell viability ratio (%)was calculated using the following equation:% viability=(absorbance of test sample/absorbance of 0 μM control)×100.Data were presented as mean± S.D.of at least three independent cultures(experiments).

Anti-viral activity test In vitro

Myocardial cells were exposed to the virus(0.5 × TC ID50,0.5 mL/well)for 1 hour,washed with DMEM three times,and incubated with a serial dilution of cinnamaldehyde(0.001-1000μM).Myocytes with viral infection were used as the CVB control.Myocytes cultured in the absence of viral infection and drug treatmentwere used as nor mal control.After 72-hours’culturing,viral titerswere measured on HeLa and cells viability was determined by MTT;briefly,whole cell lysateswere 10-fold serially diluted and were mixed with HeLa cells.At a certain dilution,countable plaques were formed,whereas either no plaques or innumerable plaques were formed at other dilutions.The negative logarithm of the dilution at which countable plaques were formed was defined as an indicator for viral titers of the whole cell lysate samples.Results of viral titers were expressed as-logTC ID50(n=3).

In vivo experim ents

A total of 106 BALB/c male mice at 4 weeks of age were included in this study.Among the 106 mice,90 were inoculated intraperitoneally with CVB3(100 × TC ID50).And sixty of those inoculated mice were given cinnamaldehyde(i.p.40 and 20 mg/kg,n=30)for 7 days and were used as cinnamaldehyde control groups, respectively.The rest 30 inoculated mice were treated with i.p.0.9%NaCl solution daily and were used as CVB-infected controls.Mice without inoculation(n= 16)were given i.p.0.9%NaCl solution daily and used as nor mal controls.Mice were executed;blood and heartswere collected on the 7thday and the 21stday. On the 7thday,the blood was subjected to 15 min 1500 r/min centrifugal treatment.Serum was abruptioed for Nitrite assay.Then mouse heartswere randomly collected.The Heatweight/bodyweight(HW/BW)ratio was evaluated.Then,one-third of each organ was fixed in 10%buffered formalin for tissue staining studies,onethird was frozen forWestern blotting analysis,and the final thirdwas homogenized inDMEM to detect viral titer.These mice(n=9 for 7 day)were excluded from the survival analysis.On the 21stday,the HW/BW ratio,survival ratio and pathological examination were evaluated.

Viral titer in heart

On the 7thDay after inoculation (n=9 for each group),one part of the heartswas removed and homogenized in 2 mL MEM.After centrifugation,the supernatantswere added into 96-well microtiter plates containing HeLa cells in DMEM supplemented with 10%fetal calf serum.Themicrotiterplateswere observed daily for 3 days to monitor the cytopathic effect.

Pathological exam ination

On the 7thDay and the 21stDay after inoculation,the heartweight(HW)and body weight(BW)were recorded.One half of each organ was fixed in 10%buffered formalin for H&E tissue staining.The other half was frozen for subsequent Western blotting analysis. Transverse sections of myocardium were graded for the severity of necrosis and mononuclear cell infiltration, with scoring from 1 to 4 as follows:Grade 1 lesions involve<25%of myocardium;Grade 2 lesions involve 25%to 50%of myocardium;Grade 3 lesions involve 50%to 75%of myocardium,and Grade 4 lesions involve 75%to 100%myocardium.Tissueswere evaluated blindly by an experienced pathologist who was familiarwith the grading system of murine viral myocarditis but had no knowledge of our study design.

W estern blotting analysis

On the 7thday after viral infection,equal amounts of total proteins(50 mg/lane)from myocardium tissues were subjected to 10%SDS-PAGE,and protein expression of NF-κB P65, iNOS,TLR4,and TNF-α was probed byWestern blotting using specific antibodies.

Nitrite assay

On the 7thday after viral infection,the blood was subjected to 15 min(1500 r/min)centrifugal treatment. Serum was abruptioed for Nitrite assay.The nitrite accumulation in supernatants was assessed by the Griess reaction.Each 50μL of culture supernatantwas mixed with an equal volume of the Griess reagent containing 0.1%N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine and 1%sulfanilamide in 5%phophoric acid.The samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min before absorbance wasmeasured at 550 nm using an automated microplate reader.A series of known concentrations of sodium nitrite was used as the standard.

Statistical analysis

Resultswere expressed as mean±standard deviation (S.D.).A database was set up with SPSS 10.0 software package(SPSS Inc,Chicago, IL)for analysis. Data were presented as themean±S.E.M.Numerical parameterswere evaluated by a Student’s t-test or analysis of variance(ANOVA).Survival rates were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method.Categorical variableswere analyzed using theχ2 test,with Yates′correction if required.Differences were considered significant at two-tailed(P<0.05).

Results

Cytotoxic activity of cinnamaldehyde aga inst myocardial cells

Myocardial cellswere treated with cinnamaldehyde at a concentration range of 0-1000μM for 72 hours before cell viabilitywas deter minedwith anMTT reduction assay.As shown in Fig.1B,cinnamaldehyde induced an overt concentration-dependent decrease in cell viability.Cell viability ofmyocardial cells in the cinnamaldehyde group were lower than nor mal control group at 10 μM(P<0.05)and 100,1000μM(P<0.01).The loss in cell viabilitywas not significant at relatively low concentrations.Cell viability was reduced to approximately 70%,54%,and 13% in cells treated for 72 hours with 0.1,1,and 10μM of cinnamaldehyde respectively.I C50value of cinnamaldehyde in inhibiting myocardial cells viabilitywas 15μM.

Anti-viral activity of cinnamaldehyde aga inst CVB3in myocardial cells

Viral titers of myocardial cells in the infected group were significantly decreased in vitro by cinnamaldehyde at 100 and 1000μM(P<0.01,n=3 each)(Fig. 1C).I C50value of cinnamaldehyde in inhibiting viral titerswas 45μM.

Cell viability of cinnamaldehyde in CVB-infected myocardial cells

Cell viability ofmyocardial cells in the cinnamaldehyde group was lower than CVB control group at 100 and 1000μM(P<0.01)(Fig.1D).

Fig.2 A:Effect of cinnamaldehyde on viral titers in the myocardium of viralmyocarditism ice on day 7(n=9); B:The content of NO in m ice blood serum ofm ice afflicted with viralmyocarditism ice inoculated virally on day 7(n=9)C:M yocardial histopathologic scores for myocard ial necrosis on Day 7(n=9 each)and 21(n=3 each)after CVB inoculation in surviv ing m ice(D)D: Effect of c innamaldehyde on the Hw/Bw ratio(All data are mean ±S.D.*P<0.05,**P<0.01,compared with CVB control.aP<0.05,bP<0.01,compared with 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde group).E:Day 21 cumulative survival after CVB3virus inoculation in 40 and 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde(n=21 each,Kaplan–M eier, log– rank test,P<0.01 compared with CVB control;aP<0.05,bP<0.01,compared with 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde group);F:The extent of myocard ial necrosis and cellular infiltration was less in the 40 and 20 mg/kg c innamaldehyde a-treated groups than in the CVB group atDay 21.a:Normal group;b:CVB group; c:40 mg/kg C innamaldehyde group;and d:20 mg/kg C innamaldehyde group.(All data are mean±S.D.*P <0.05,**P<0.01,compared with CVB control.aP< 0.05,bP<0.01,compared with 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde group).NO content in mouse blood serum

Viral titers ofin vitroexper iments

On 7thDay after inoculation,the viral titer in the myocardium was evaluated in Hela cells grown in microtiter plates.The results showed that the viral titerswere significantly decreased in 40 and 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde treatment groups compared with the CVB group (P<0.01).However,there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups(P> 0.05)(Fig.2 A).

On the 7thday after viral infection,the content ofNO in mice blood serum was evaluated by an automated microplate reader.Results showed that NO content was significantly reduced by cinnamaldehyde trea tment compared with the CVB group(P<0.05).There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups(P>0.05)(Fig.2B).

Heart tissue histopathologic observation

On the 7thDay and the 21stDay after viral infection,the histopathologic score of 40 and 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde treatment group was notably reduced(p<0.01,n =9 each)compared with that of the model group (Fig.2C).On the 21stDay,microscopic observation revealed that the inflammatory infiltration focus in the CVB group was increased compared with the cinnamaldehyde groups,and there was obviousmyocardial calcium(n=3 each).The inflammatory infiltration focus in 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde group was reduced compared with the 40 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde trea tment group(P<0.05)(Fig.2C,F).

Hw/Bw ratio

On the 21stDay after inoculation,the Hw/Bw ratio in myocardium was evaluated.The results show that the Hw/Bw ratiowas significantly reduced in the cinnamaldehyde groups compared with the CVB group(P< 0.05).However,there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups(P> 0.05)(Fig.2D).

Survival of an imals

The 21-day survival rate in the cinnamaldehyde groups (52.4%,47.6%,n=21)was significantly greater than the CVB group(14.2%,n=21;P<0.05)(Table 1).The median survival time was significantly longer than that of the CVB group (P<0.05,Figure 2E).A group comparison of 40 and 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde groups did not reach statistical significance (P>0.05)(Fig.2E).

able 1 Death rate and median survival t ime in m ice with viralmyocarditis at the 21stDay after viral inoculation

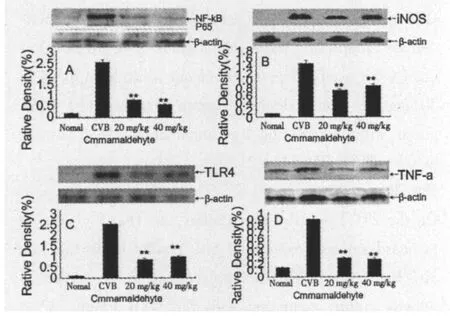

Effects of c innamaldehyde,cinnam ic acid on NF-κB P65,iNOS,TLR4,and TNF-α expression in the myocardium of viralmyocarditism ice

On the 7thday after inoculation,expression of NF-κB P65, iNOS,TLR4 and TNF-α was dramatically increased in the CVB group,while trea tmentwith 40 and 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde inhibited the expression of this protein(P<0.05)(Fig.3).There was no statistical significance be tween the two treatment groups(P >0.05).

Fig.3 W estern blot depicting NF-κB P65,iNOS,TLR4, and TNF-α,expression in the myocardium of m ice afflicted with viralmyocarditism ice inoculated virally on day 7(n=9)A:NF-κB P65;B:iNOS;C:TLR4;D:TNF-α(All data are mean ±S.D.*P<0.05,**P<0.01,compared with CVB control.aP<0.05,bP<0.01,compared with 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde group).

D iscussion

Coxsackievirus B3(CVB3)is a major cause of acute myocarditis,a serious condition that is refractory to treatment.Myocardial damage results in tissue remodeling that,if too extensive,may contribute to disease itself.Acute CVB myocarditismay result in serious longter m sequelae,including chronic myocarditis that can develop into dilated cardiomyopathy,a terminal condition requiring transplantation.At present,the trea tment of viral myocarditis is primarily supportive;specific therapies are lacking and in great demand.The mechanis m(s)by which CVB3induces acute and chronic myocarditis is unclear.During acute infection,both direct virus-mediated cytolysis and immune-mediated destruction of CVB3-infected myocardium contribute to myocardial damage.The chronic disease is thought to be primarily immunopathological,but the antigenic target of the immune response is controversial as evidence exists both for autoimmunity and for ongoing responses to persistent viral materials.The toxicological features of cinnamaldehyde have been well established.Our data showed that an IC50value of cinnamaldehyde in inhibiting myocardial cells viabilitywas only 15μM.Interestingly,our studies showed that treated by 100-1000 μM cinnamaldehyde in CVB3-infected myocardial cells for 72 hoursproduced amarginally significant reduction in viral titer(P<0.01).However,little or no cell viabilitywas observed at the same concentration,there was no statistically significant difference be tween the CVB groups and cinnamaldehyde groups(P<0.05).So cinnamaldehyde inhibited viral production in myocardial cells with overt toxic effect in vitro.Nonetheless,it possesses anti-viral activity by i.p.in vivo.Although culture techniques provide investigatorswith the opportunity of s implifying the environment to address specific research questions,cell cultures cannot currently provide a realistic cellular environment that duplicates conditions found in the heart.CVB3myocarditis animal models allow the dissection of the acute viral phase of the disease from the chronic,autoimmune component. These findings suggest that either cinnamaldehyde has anti-viral effects on viralmyocarditis by immune-mediated.

Viralmyocarditiswhich is frequently clinical occurring disease severely threatens people's health.However, there is still no effective drug to treat this disease. CVB3infection is believed to be a principle trigger leading to human myocarditis.Virus persistence and myocardial inflammation/endothelial activation are reported to be associated with endothelial dysfunction of the coronary microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction could occur independently ofmyocardial inflammation in patients with virus persistence.Persistent viral infection-induced release of the pro-inflammatory factors such as NF-κB,NO,iNOS and TNF-α has been demonstrated in viralmyocarditis[8].Activation of NF-κB mediated through TLR4 was completely abolished in MyD88/TR IF double-knockout cells demonstrating thatMyD88 and TR IF are the major adaptor molecules required for TLR4 signaling pathways.The activation of TLR4 signaling by bacterial ligands leads to the expression of pro-inflammatory gene products such as cytokines,COX-2,and iNOS.TLR4 can be also activated by non-microbial components such as fibronectin,saturated fatty acid,and modified low-density lipoprotein resulting in the induction of sterile inflammatory responses.Indeed,the accumulating evidences show that the activation or the suppression of TLR4 is implicated in the development and progression of various inflammatory diseases[9].TLR4 is also activated by CVB3persistence effect.These change could cause a serial of inflammatory response by TLR4-NF-κB signal transduction passway,induce further cellular apomorphosis and necrosis in myocardium,which results backward heart failure(CCF)in mice with viral myocarditis. Therefore,Inhibitors of CVB3duplicating,TLR4-NF-κB signal transduction pass way not only possess important significance on illuminating of pathology turnover of viralmyocarditis,but also establish empirical foundation on effective drug exploitation of viralmyocarditis.However,the effect as to inhibiting TLR4-NF-κB signal transduction passway on viralmyocarditis viralmyocarditis has not been clearly elucidated.NO is an endogenous free radical species that is synthesized from l-arginine by nitric oxide synthase(NOS)in various animal cells and tissues.Small amounts of NO are important regulators of physical homeostasis,whereas large amounts of NO have been closely correlated with the pathophysiology and inflammation of viral myocarditis. Thus,measuring ofNO production may be a method for assessing the anti-inflammatory effects of drugs.Cinnamaldehyde inhibited LPS-induced iNOS expression and NO production,as well as LPS-induced cytokine production as seen atμM concentration ranges[10].It was observed that cinnamaldehyde suppressed lipopolysaccharide(LPS)-induced NF-κB activation.It has been demonstrated that the molecular target of cinnamaldehyde in TLR4 signaling isoligomerization processof receptor,but not downstream signaling molecules suggesting a novelmechanis m for anti-inflammatory activity of cinnamaldehyde.This observation received additional support from our current study in which intraperitoneal injection of cinnamaldehyde at the same concentrations reduced myocardial viral titer,reduced blood NO content,upregulated myocardialNF-κB P65,iNOS,TLR4, and TNF-αexpression in conjunction with improved inflammatory cell infiltrate in myocardium of CVB3-infected mice 7 days after viral inoculation(P< 0.05-0.01).The inter-group comparison between 40 and 20mg/kg cinnamaldehyde was not statistically significant.The survival rate was higher with less severe histopathologic changes(necrosis,degeneration,and cellular infiltration)in the two trea tment groups 21 days after viral inoculation(P<0.05-0.01 compared to the CVB group).The inflammatory infiltration focus in 20 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde trea tment group was reduced compared to the 40 mg/kg cinnamaldehyde trea tment group 21 days after viral inoculation(P<0.05).The understanding of cinnamaldehyde has an anti-inflammation effect on immune damage induced by persistent viral infection wasinhibiting TLR-4-NF-κB signal transmission pathwaymoderately.

To the bestofour knowledge,this is the first report cinnamaldehyde has a therapeutic effecton viralmyocarditis through inhibiting TLR-4-NF-κB signal transmission pathway.This work suggests that cinnamaldelyde may be a new source for the therapeutic drug used in the initial stage of viralmyocarditis by inhibiting TLR-4-NF-κB signal trans mission pathwaymoderately.

1 Fair weatherD,Frisancho-Kiss S,Yusung SA,et al.Rose. IL-12 protects against coxsackie virus B3-induced myocarditis by increasing IFN-γand macrophage and neutrophil populations in the heart.J Immunol,2005,174:261-269.

2 Paananen A,Ylipaasto P,Rieder E,et al.Molecular and biological analysis of echovirus 9 strain isolated from a diabetic child.J M ed V irol,2003,4:529-537.

3 Huang JQ,Wang S W,Luo XX,et al.Cinnamaldehyde reduction of platelet aggregation and thrombosis in rodents.Thrombosis Res,2007,119:337-342.

4 FriedmanM,Henika PR,Mandrell RE.Bactericidal activities of plant essential oils and some of their isolated constituents againstCampylobacter jejuni,Escherichia coli,Listeriamonocytogenes,and Sa lmonella enterica.J Food Prot,2002,65: 1545-1560.

5 Hayashi K,Nmanishi I,Kashiwayama Y,et al,Inhibitory effect of cinnamaldehyde,derived from Cinnamomi cortex,on the growth of influenzaA/PR/8 virusin vitroandin vivo.Antiviral Res,2007,74:1-8.

6 Yamashita M,Nakayama T.Progress in allergy signal research on mast cells:regulation of allergic air way inflammation through toll-like receptor 4-mediated modification of mast cell function.J Phar macol Sci,2008,106:332-335.

7 Youn HS,Lee JK,et al.Cinnamaldehyde suppresses toll-like receptor 4 activation mediated through the inhibition of receptor oligomerization.B iochem Phar m,2008,75:494-502.

8 PeterAlter,Heinz Rupp,BernhardMaisch.Activated nuclear transcription factorκB in patientswith myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy-relation to inflammation and cardiac function.B iochem icaland B iophysical Res Comm unications, 2006,339:180-187.

9 Lee JY,HwangDH,The modulation of inflammatory gene expression by lipids:mediation through Toll-like receptors.M ol Cells,2006.21,174-185.

10 Tung YT,ChuaMeng-Thong,Wang SY,et alAnti-inflammation activitiesof essentialoil and its constituents from indigenous cinnamon(Cinnam om um osm ophloeum) twigs.B ioresource Technology,2008,99:3908-3913.