Taphonomy of Early Triassic fish fossils of the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member of the Sulphur Mountain Formation near Wapiti Lake, British Columbia, Canada

Karen Anderson, Adam D.Woods

Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, P.O.Box 6850, CA 92834-6850, USA

1 Introduction and background*

Taphonomy describes the events that occur to an organism from death to fossilization (Efremov, 1940), and is not only an important tool in understanding the processes that affect deceased organisms, but also provides a mechanism to reconstruct past depositional environments as well as a means to gain a better understanding of the ecology of organisms prior to their demise (e.g., Behrensmeyer and Kidwell, 1985; Brett and Baird, 1986; Elder and Smith,1988; Weigelt, 1989; Fernandez-Jalvo, 1995; Martin-Closas and Gomez, 2004; Fürsichet al., 2007; Mapeset al.,2010; Histon, 2012; McDonaldet al., 2013; Peterson and Bigalke, 2013; Sansom, 2013; Sorensen and Surlyk, 2013).Taphonomic studies of fish have typically involved study of the decay of modern fish (e.g., Parker, 1970; Britton,1988; Weigelt, 1989; Minshallet al., 1991; Hankin and McCanne, 2000; Whitmore, 2003), or the examination of fossil fish from ancient lacustrine deposits (e.g., McGrew,1975; Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988; Ferber and Wells, 1995; Wilson and Barton, 1996; Barton and Wilson,2005; Caprileset al., 2008; Malendaet al., 2012; Mancuso,2012).The taphonomy of fish in marine environments is less well understood, and has been mostly concerned with the causes of mortality (e.g., Brongersma-Sanders, 1957),including sudden temperature changes (e.g., Gunter, 1941,1942, 1947), cold shock and hypothermia (e.g., Baughman, 1947; Gilmoreet al., 1978; Donaldsonet al., 2008),and low dissolved oxygen levels (e.g., Smith, 1999).One of the few studies to examine post-mortem processes in marine fishes was by Sch?fer (1972), which documented the f l oatation response due to internal gas production of eight species of deceased marine fishes and the subsequent loss of body parts from f l oating carcasses.Taphonomic analysis of marine fishes in the geologic record is limited when compared to those of lacustruine deposits,probably due to a greater likelihood of preservation of fish remains in relatively low energy lake environments with high sedimentation rates.Taphonomic studies of marine fishes include fossils from Cenozoic (Bieńkowska, 2004,2008; Bieńkowska-Wasiluk, 2010; Carnevaleet al., 2011;Asanoet al., 2012), Mesozoic (Tintori, 1992; Vulloet al.,2009; Chelloucheet al., 2012), and Paleozoic-aged rocks(Burrow, 1996; Cloutieret al., 2011; Luk?evi?set al.,2011; Vasi?kovaet al., 2012).Ancient marine fish have recently been subjected to semi-quantitative taphonomic analysis, however, the number of such studies is limited(Bieńkowska-Wasiluk, 2010; Cloutieret al., 2011; Chelloucheet al., 2012).

The Early Triassic fossil fishes of Wapiti Lake, British Columbia, Canada are ideal for taphonomic study, as the specimens are frequently whole and well preserved.Preservation was enhanced by deposition in quiet waters with little to no disturbance from ocean currents and suffi ciently low oxygen levels in the surrounding waters that excluded scavengers (Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith 1988).Furthermore, Early Triassic marine fishes had heavy ganoid or cosmoid scales that were not prone to rapid decay, and when coupled with the interlocking arrangement of the scales, provided a resistant barrier to environmental conditions and scavengers (Sch?fer, 1972; Weigelt, 1989;Neuman, 1996).In addition, the heavy scales increased the odds that the fish would sink after death and lead to wellpreserved, articulated specimens (Neuman, 1996).

1.1 Geologic background

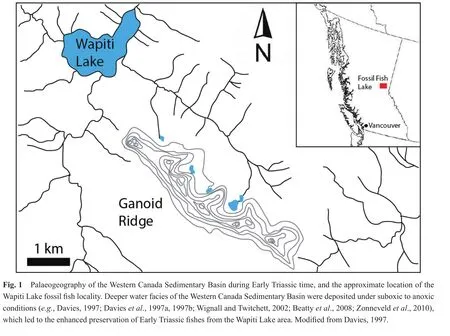

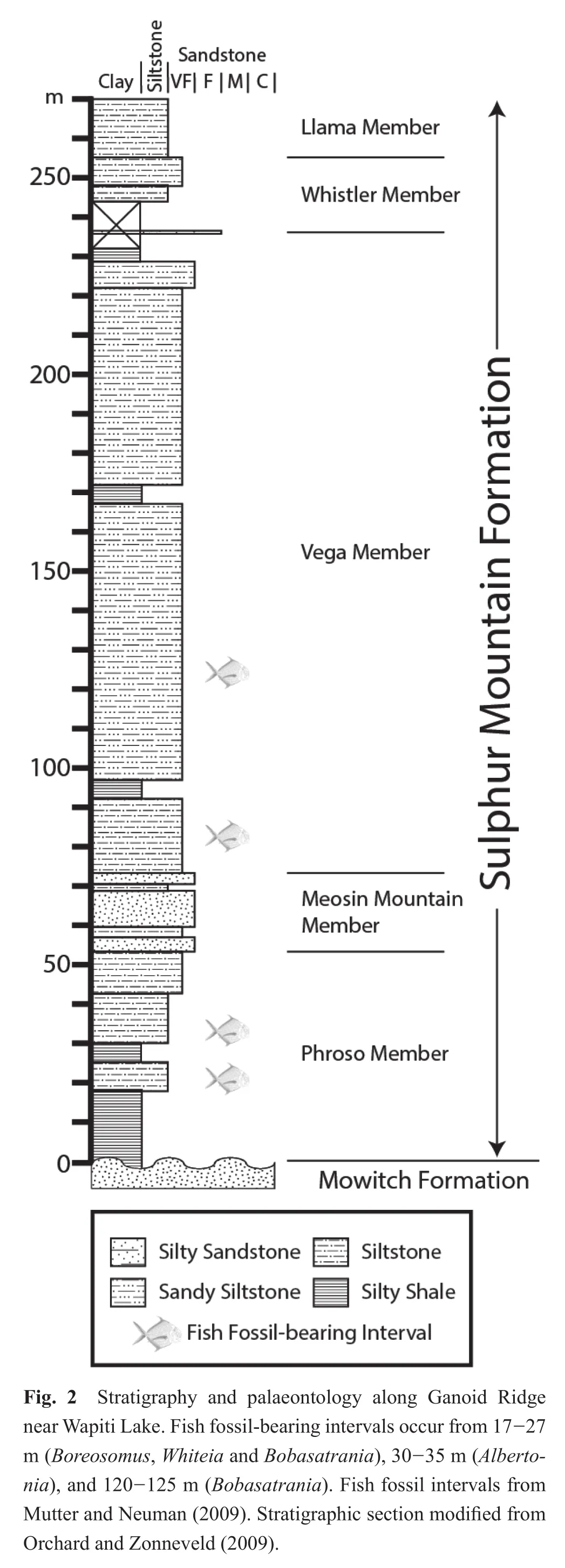

The fish fossils examined for this study were collected from talus shed from multiple fossil horizons that occur in the Sulphur Mountain Formation at Ganoid Ridge, near Wapiti Lake, British Columbia, Canada (Figs.1, 2)(Gibson, 1972).The Sulphur Mountain Formation ranges in thickness from 225 to 250 meters at Ganoid Ridge, was deposited from the lowermost Triassic to the Middle Triassic, and is divided into three Lower Triassic Members:(1)The recessive basal Phroso Member, which ranges from 45-55 m thick, and consists of thin, planar-bedded organic-rich dolomitic silty shale; (2)The Meosin Mountain Member, which is approximately 12 meters thick,resistant, and composed of very fine-grained, well-sorted sandstone that may be current-rippled or planar-laminated;(3)The Vega Member is approximately 195 meters thick,and consists of interbedded calcareous to dolomitic quartzrich sandstone and organic-rich silty shale (Orchard and Zonneveld, 2009).In addition, the Sulphur Mountain Formation also includes two Middle Triassic members, the Whistler Member and the Llama Member (Orchard and Zonneveld, 2009).Fossil fish occur at multiple horizons within the Phroso Member and Vega Member at Ganoid Ridge and include at least 17 different taxa of bony fish and 4 different taxa of cartilaginous fishes; other fauna include ichthyosaurs, marine reptiles, phyllocarids, brachiopods, bivalves, ammonoids and conodonts (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Brinkman, 1988; Callaway and Brinkman,1989; Neuman, 1992; Mutter and Neuman, 2009; Orchard and Zonneveld, 2009).Much of the Sulphur Mountain Formation at Ganoid Ridge was deposited under quiet,low energy conditions with reduced benthic oxygenation as suggested by the fine-grained nature of the unit, a lack of bioturbation within the fish-bearing intervals, and the excellent preservation of fossil remains, including delicate dermal denticles of the chondrichthyan (shark)Listracan?thus(Gibson, 1975; Davieset al., 1997a; Mutter and Neuman, 2009).Many of the fossil fish specimens from Ganoid Ridge, including those examined for this study, were collected by previous workers from talus; because most fossils are not foundin situ, it is diff i cult to match an individual fossil to a specif i c stratigraphic horizon (Neuman,1992; Mutter and Neuman, 2009), however, most of the fish are early Olenekian in age (Orchard and Zonneveld,2009), although some Induan-aged fish fossils are also probably present (Mutter and Neuman, 2009).

1.2 Lower Triassic fossil fish of Wapiti Lake

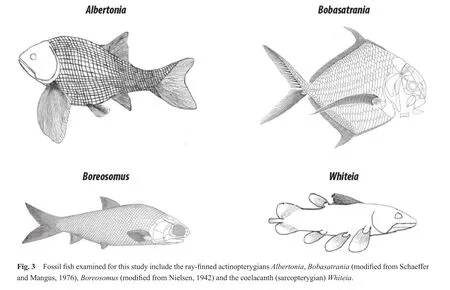

Four genera of Early Triassic marine fishes that are represented by numerous, well-preserved, complete specimens were selected for the current taphonomic research.The four fish genera, each with a distinctive morphology that is unlike the other fishes selected for this research,include the ray-finned actinopterygiansAlbertonia, Boba?satrania,andBoreosomusand the coelacanth (sarcopterygian)Whiteia.Specimens from all four genera consist of articulated and well-preserved fishes with heavy scales that are surrounded by a matrix of well-sorted, fine-grained,black siltstone.The scales are well defined on most specimens and, in most cases decay has not progressed to the stage where only the internal structures (i.e., skeleton or individual bones)are exposed and visible.

1.2.1Albertonia

Albertoniais endemic to British Columbia and Alberta(Neuman, 1992, 1996; Davieset al., 1997b); fossils ofAlbertoniaare found in a narrow interval, approximately 30-35 m above the base of the section (Neuman, 1992)(Fig.2).Albertoniahad a deep body, long pectoral fins,and a well-developed caudal fin (Fig.3);Albertoniawas a nibbler or grazer based on its weak marginal dentition and a lack of pharyngeal teeth (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976;Neuman, 1992, 1996).Albertoniawas likely a strong, but slow swimmer, and lived at moderate depths (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992).

1.2.2Boreosomus

Boreosomus-bearing beds are located 17-27 m above the base of the section at Wapiti Lake (Mutter and Neuman,2009), and have been found in association with late Induan (i.e., Dienerian)conodonts (M.Orchard, pers.comm.,2004 in Mutter and Neuman, 2009).Boreosomushas also been collected from Spain (Vía Boadaet al., 1977),East Greenland (Nielsen, 1942), Alaska (Patton and Tailleur, 1964), China (e.g., Chow and Liu, 1957), Svalbard(e.g., Stensi?, 1921)and northwestern Madagascar (Beltan, 1996).Boreosomushad large eyes and a small, fusiform body, suggesting it was a generalist swimmer (Fig.3)(Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1996; Barbieri and Martin, 2006).Small conical teeth suggestBoreoso?musgrazed or fed on plankton, detritus, larval fishes, soft animals,etc.(Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Beltan, 1996),probably in the euphotic zone (Beltan, 1996).

1.2.3Whiteia

Whiteiafossils have been found 17-27 m above the base of the section at Wapiti Lake (Mutter and Neuman,2009), as well as in Lower Triassic strata from East Greenland (e.g., Stensi?, 1932)and Madagascar (e.g., Moy-Thomas, 1935).Whiteiaare a type of coelacanth and are structurally different from the ray-finned actinopterygians(Fig.3).A distinctive feature is the caudal fin, which has three lobes, consisting of a symmetrical upper and lower lobe and a separate middle lobe (Moy-Thomas, 1935;Neuman, 1996).In addition, coelacanths have two distinct dorsal fins (ancient actinopterygians had only one dorsalfin); only the posterior of the two dorsal fins is lobed(Moy-Thomas, 1935).The anterior dorsal fin resembles the ray fins of actinopterygians; the posterior dorsal fin,pectoral fins and pelvic fins are lobed and have a rounded morphology (Moy-Thomas, 1935).The rounded fin structure ofWhiteiasuggests slow movement, and sculling type locomotion (Forey, 1997; Fricke and Hissmann, 1992).Whiteialikely stalked and lunged at prey (Neuman, 1996);small teeth suggestWhiteiaate small organisms in addition to phytoplankton, algae, and organic detritus (Beltan,1996).

1.2.4Bobasatrania

Bobasatraniaare found within two stratigraphic horizons at Wapiti Lake: from approximately 17-27 m and approximately 120-125 m above the base of the section(Neuman, 1992; Mutter and Neuman, 2009).Bobasatra?niahas also been found in Lower Triassic strata of Idaho(Dunkle, pers.comm., 1974 in Schaeffer and Mangus,1976), Madagascar (e.g., Lehmanet al., 1959), Greenland(e.g., Nielsen, 1952)and Spitzbergen (e.g., Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976).The Wapiti Lake specimens ofBobasa?traniafound higher in the section are some of the largest fossil fish specimens found in the assemblage and are larger than mostBobasatraniafound around the world(e.g., Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976), reaching lengths of up to one meter (Neuman, 1996).Smaller fossil specimens ofBobasatraniaprimarily found lower in the section may represent a different species (Neuman, 1996).

Bobasatraniaare compressed laterally, resulting in a diamond-shaped morphology (Fig.3)(Russell, 1951).A well-developed and deeply-forked caudal fin, long fins on the dorsal and ventral parts of the body, and long, fan-like pectoral fins high on the abdomen are indicative of precise position control coupled with short bursts of speed to catch prey (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992, 1996);Bobasatranialikely lived near the seaf l oor in quiet waters(Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992, 1996; Barbieri and Martin, 2006).Crushing teeth suggest thatBoba?satraniafed on crustaceans (Neuman, 1992, 1996).Boba?satraniadid not have pelvic fins (Neuman, 1992, 1996).

2 Methods

All available fossil specimens ofAlbertonia,Bobasa?trania,BoreosomusandWhiteiawere examined from the collections of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada, as well as from the collections of the University of Alberta Laboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology and the Paleontology Museum, Edmonton,Alberta, Canada.Of the 379 specimens photographed and described for this study, 145 were complete specimens that could be used for taphonomic analysis.Additional partial specimens were included in the determination of fin tetany or body tetany when possible.

Data collected for each specimen included specimen number (which was assigned by the museum or university where the specimen is housed: UALVP for the University of Alberta Laboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology, TMP for the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology), fish genus, geologic age, locality, cirque where the fossil was found along Ganoid Ridge (if given), date of collection,UTM/ fi eld site coordinates (if recorded), standard length of the fish if complete (in millimeters; standard length =the length from the snout to the caudal peduncle), ichnofabric index of the surrounding sediments (Droser and Bottjer, 1986), and a written description of the preservational condition of the fossil.At the time the fossil fishes were examined, any disarticulated body parts were identifi ed in a photo (or line drawing)of the fish, along with a notation of the proximity of the disarticulated part.Be-cause taphonomic ranking required examination of the entire fish, only complete specimens were considered; in the case of broken fossils, partially complete fish fossils were considered only if the majority of the fish was visible and taphonomic data could be collected.Examination of entire fish fossils likely introduced some taphonomic bias into this study in that not all available fossil material was examined (or collected in the fi eld), and the most disarticulated fossils, and therefore those that underwent the greatest degree of decay may have been missed.However,limiting this study to only entire fish fossils is considered to be the most careful means to determine the sequence of fish decay, as analysis of individual, detached parts (e.g.,fins, scales, material within coprolites,etc.)would lead to greater odds of analyzing the same individual fish multiple times, and introduce what would likely be an even greater taphonomic bias.

2.1 Taphonomic model

Individual fish fossils examined for this study ranged from extremely well preserved with little alteration of the fish carcass to varying degrees of distortion, decay and scattering of elements; therefore, it was important to formulate a scale that could be used to semi-quantitatively analyze taphonomic loss over a wide range of preservational stages.Wilson and Barton (1996)developed a taphonomic sequence for lacustrine fossil fishes that utilized a ranking system to examine the differing degrees of decay and disarticulation of fossil fishes; their study served as the basis for the taphonomic stages used in this study.Similar methods of semiquantitatively determining taphonomic loss in fishes have been used by multiple other studies(e.g., McGrew, 1975; Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988;Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005; Bieńkowska-Wasiluk, 2010; Cloutieret al., 2011; Chelloucheet al.,2012; Mancuso, 2012).

In order to establish a sequence of decay and disarticulation for each genus examined for this study, color photographs of each complete fish specimen were initially placed in a sequence of progressive disarticulation.Next,the preservational condition of the skull, dorsal fin, pelvic fin, pectoral fin, anal fin, caudal fin, and the body were independently noted and each was assigned a number based on a 1 to 5 taphonomic scale, where stage 1 indicated that the region of interest was well preserved, and stages 2 through 4 indicated successive degrees of decay and disarticulation.Stage 5 represented complete disarticulation,scattering and loss of skull elements, fins, or scales (in the case of the body)(Table 1).

Previous studies by McGrew (1975), Elder (1985), Elder and Smith (1988), Wilson and Barton (1996), Whitmore (2003)and Barton and Wilson (2005)have noted that the skull appears to be the first region of a fish to decay and disarticulate; therefore, for the current study, taphonomic data were normalized to the skull.The degree of decay and disarticulation of the skull, or the “skull taphonomic stage,” was determined first, and the degree of decay and disarticulation of the dorsal fin, anal fin, pectoral fin, pelvic fin, caudal fin as well as the degree of preservation of the body were determined subsequently.

2.2 Tetany

Tetany is a form of severe postmortem muscular contraction, which is often expressed as an open mouth, expanded or fanned and stiffened fins, and, less commonly an arched body; tetany is considered to be an indicator of anoxic or hypoxic conditions in aquatic environments,although tetany can also be due to temperature shock or poisoning by plant toxins (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976).Skull decay was extensive for the fossil fishes examined for the current research and therefore it was typically not possible to collect data related to whether the mouth was open or closed.The exclusion of data related to the position of the jaw is supported by the work of Barton and Wilson (2005)who note that relative tetany was best assessed by observing the fins.

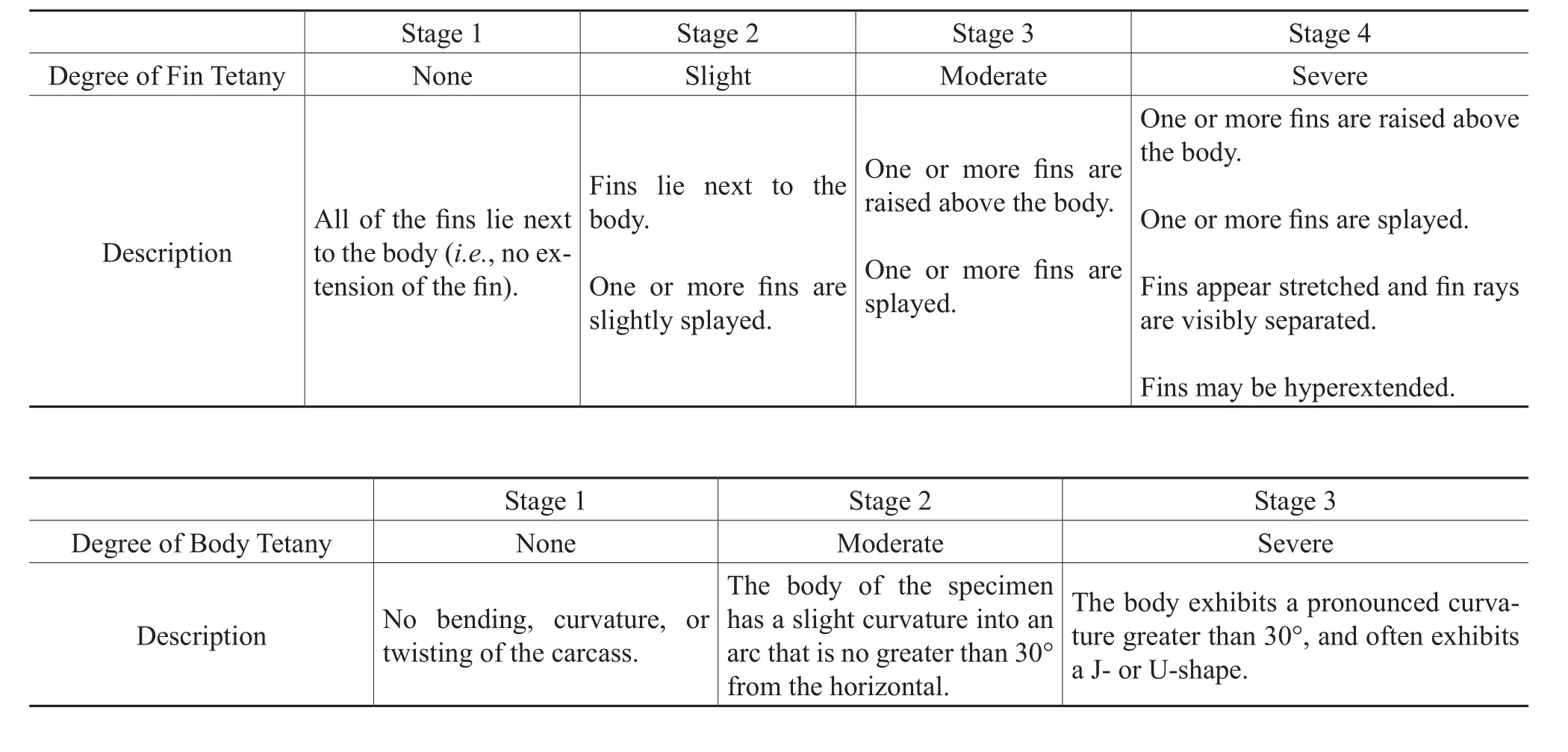

2.2.1Criteria for determination of tetany of fins

Fin tetany was evaluated based on the presence of at least two fossil fins other than the caudal fin; therefore the entire fish was not necessary for determination of fin tetany.The fins (excluding the caudal fin)were examined and qualitatively assigned a stage ranging from 1 to 4 (modifi ed from Barton and Wilson, 2005)based on progressively greater angles of extension of the fin away from the body and the expansion and separation of the fin rays, which resulted in an increased amount of exposed fin surface area(Table 2).It was necessary for the fins of the fish fossils to be in fairly good condition for fin tetany to be determined;tetany was not determined for those fossils where the fins had detached from the body, exhibited excessive decay, or were absent.

Tetany data were collected forAlbertoniaandWhiteiabecause their fins are large and easily ranked.Whiteiahas two dorsal fins; the first dorsal fin is not lobed, but is fanshaped, similar to the dorsal fin of a ray- finned fish.All fins were considered together for both fish genera, and the non-lobed first dorsal fin ofWhiteiawas not given any spe-

cial consideration from the lobed fins.BobasatraniaandBoreosomuswere not included because the fins ofBobasa?traniaare small and the fins are extended in all specimens.Boreosomuswas not considered for determination of fin tetany because the fins were often detached, highly fragmented, or missing.

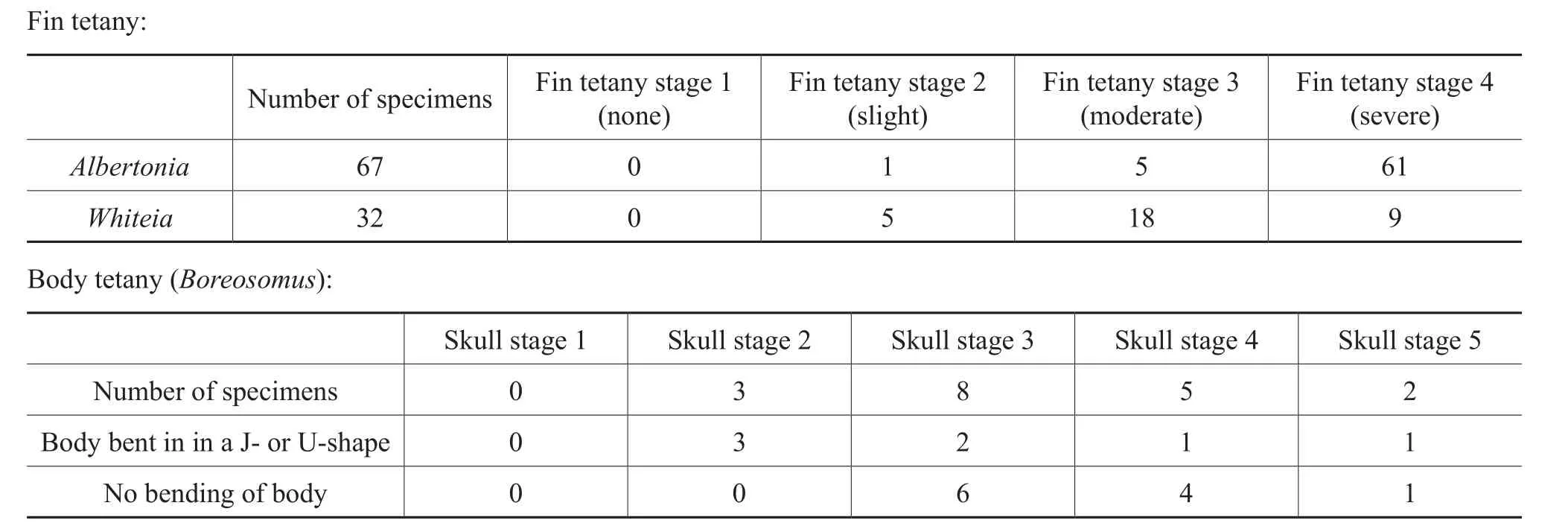

Table 2 Stages of tetany for Albertonia and Whiteia fins and Boreosomus body

2.2.2Postmortem bending of the body: Another possible indicator of tetany

In addition to fin tetany, tetany may also be expressed by an arched body or a body bent into a J- or U-shape; arching of the body has been observed in previous studies of fishes that have been subjected to hypoxic (low oxygen)or anoxic conditions (e.g., Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988;Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005).Boreosomus,whichwas not included in the examination of fin tetany because of the frequent loss of the fins, was examined for body tetany because the slender, fusiform morphology of the fish is expected to show evidence of body tetany if the fish was exposed to detrimental environmental conditions.AllBoreosomusspecimens that were assigned taphonomic stages were also visually examined and placed in one of three stages of body tetany (Table 2).

3 Results

3.1 Ichnofabric

The fossil fishes found within the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member are preserved within fine-grained siltstone that breaks into flat slabs; the rock varies in color from dark brown to dark gray to black (Gibson, 1972, 1975;Neuman, 1992, 1996; Davies, 1997; Davieset al., 1997a,1997b; Orchard and Zonneveld, 2009).The fine siltstones that surround the four genera of fossil fishes (n= 379)examined for this research have an Ichnofabric Index of 1,implying that the sediments were undisturbed by bioturbation (Droser and Bottjer, 1986).

3.2 Degree of taphonomic loss

All specimens of each of the 4 genera examined for this study underwent some degree of skull decay.Therefore,there were no specimens with a ranking of taphonomic stage 1 for the skull.

3.2.1Albertonia

A total of 155 specimens ofAlbertoniawere examined and photographed; of those, 73 specimens (47%)were complete and suitable for determining taphonomic stages.The standard length ofAlbertoniaexamined for this study varied from 75 mm to 390 mm.The pectoral, anal, and dorsal fins were either extended or pressed against the body.

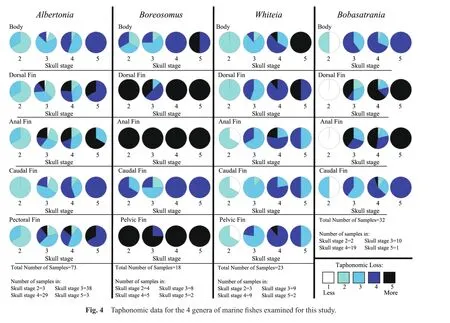

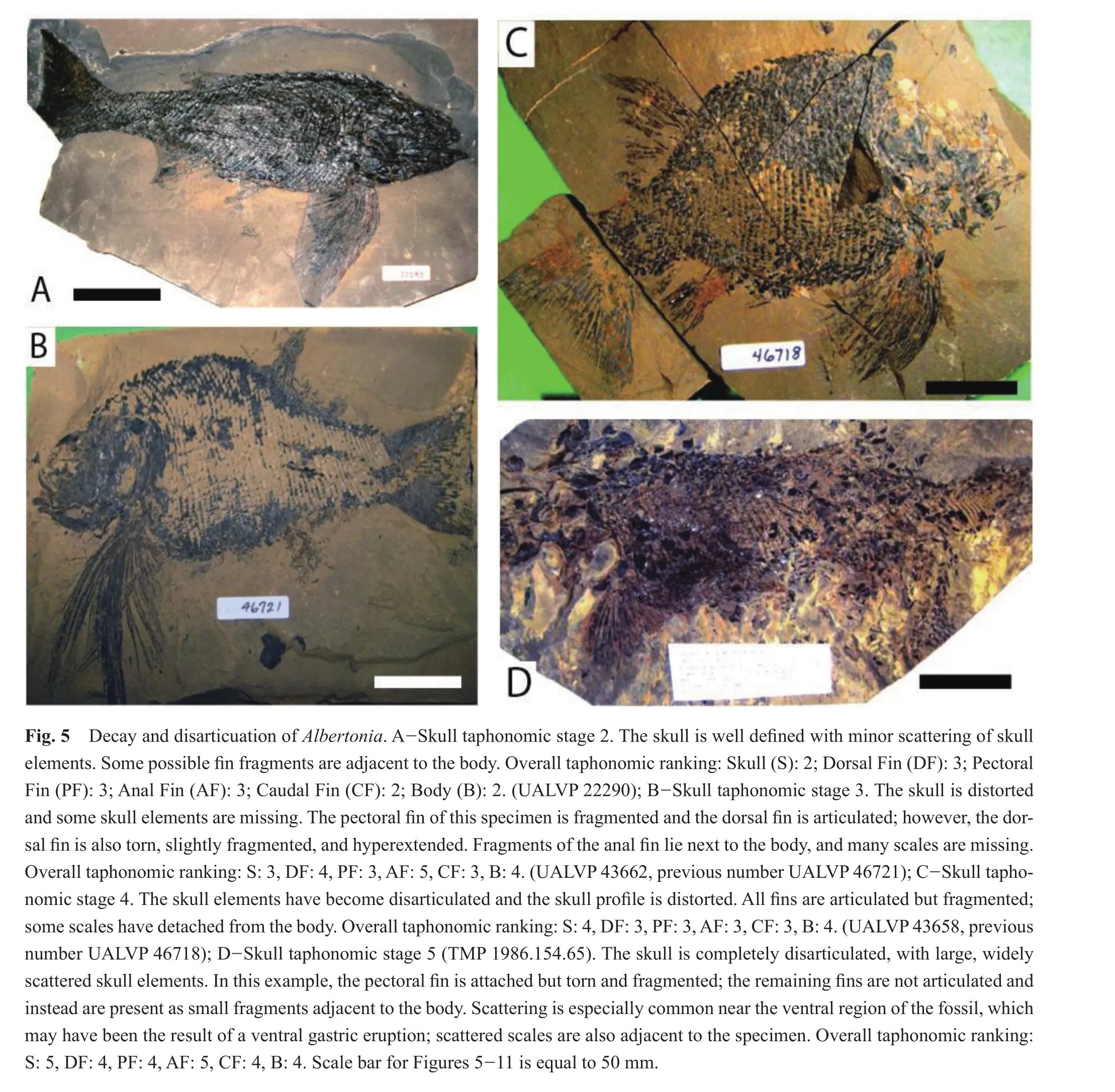

In the early stages of skull decay and disarticulation,at skull taphonomic stage 2 (n= 3), the caudal fin was the best preserved with all specimens within taphonomic stage 2 (Figs.4, 5A; Table 3).The remaining fins and body were assigned to taphonomic stage 2 (2 specimens)and 3(1 specimen).

The largest number ofAlbertoniaspecimens (n= 38)had a skull taphonomic stage of 3.At this taphonomic stage, the anal fin underwent the greatest degree of taphonomic loss while the body and caudal fin were the better preserved (Figs.4, 5B; Table 3).The smallest fin, the anal fin, exhibited some fragmentation and had a greater degree of decay and disarticulation when compared to the dorsal or pectoral fins.For the anal fin, 6/38 specimens were classi fi ed as taphonomic stage 4, and 9/38 taphonomic stage 5.The remainder of the samples were assigned taphonomic stage 1 (2/38), 2 (10/38), or 3 (11/38).The dorsal fin of the majority of specimens was ranked at taphonomic stage 2 or 3 (13/38 and 14/38, respectively), with most of the remainder at taphonomic stage 4 or 5 (6/38 and 4/38, respectively).The dorsal fin of a single specimen exhibited no evidence of decay or disarticulation (taphonomic stage 1).The pectoral fin for most specimens was assigned to taphonomic stage 3 (16/38)or 4 (10/38), with the difference divided between taphonomic stage 1 (1/38), 2 (7/38),or 5 (4/38).The caudal fin of 28/38 of the specimens was assessed as taphonomic stage 2 or 3 (17/38 and 11/38,respectively), with the remainder in taphonomic stage 1(2/38)or 4 (8/38).The body of most specimens was ranked taphonomic stage 3 (26/38), with the difference divided between taphonomic stage 1 (2/38), 2 (5/38)or 4 (5/38).

As skull decay and disarticulation progressed into taphonomic stage 4 (n= 29), the dorsal and anal fins of several specimens were extremely fragmented and detached, but were typically in relative position next to the body (Figs.4, 5C; Table 3).The small anal fin continued to exhibit the greatest degree of taphonomic loss, with most(9/29, 31%)specimens within taphonomic stage 5.The anal fin of the remainder of the specimens was assigned to taphonomic stage 2 (5/29), 3 (10/29)or 4 (5/29).The dorsal fin exhibited slightly less taphonomic loss than the anal fin with 8/29 and 7/29 within taphonomic stage 4 or 5, respectively.The dorsal fin of the remaining specimens was assessed as taphonomic stage 2 (4/29)or 3 (10/29).The pectoral fin was often extended and sustained some decay and disarticulation but was better preserved than the smaller dorsal and anal fins, with 3/29, 13/29, 9/29 and 4/29 in taphonomic stages 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively.The caudal fin underwent less decay and disarticulation than each of the other fins, with 3/29 in taphonomic stage 2,10/29 in taphonomic stage 3, and 16/29 in taphonomic stage 4.The body was divided between taphonomic stage 3 or 4 (14/29 and 13/29, respectively)for most specimens,with the difference in taphonomic stage 2 (2/29).

During skull taphonomic stage 5 (represented by 3 specimens), the soft tissue of the skull decayed to the point where the skull elements were dissociated and scattered;consequently, the anterior region, which includes the dorsal and pectoral fins, also underwent a great deal of decay and disarticulation, with the dorsal and pectoral fins at taphonomic stage 4 (2/3)or taphonomic stage 5 (1/3)(Figs.4, 5D; Table 3).The specimens were divided between taphonomic stage 4 (1/3)and 5 (2/3)for the anal fin.The posterior region of the specimen, including the caudal fin, was best preserved with all specimens within taphonomic stage 4.The body was also slightly better preserved than the skull, dorsal fin, pectoralfin, oranalfinat taphonomic stage 4.

3.2.2Boreosomus

Boreosomushad the least number of fossil specimens for study.A total of 45 specimens ofBoreosomuswere examined and photographed; of those, 18 specimens (40%)were complete and suitable for taphonomic analysis.The standard length ofBoreosomusexamined for this study ranges from 83 mm to 225 mm.Many of the fins (except the caudal fin)ofBoreosomuswere missing.

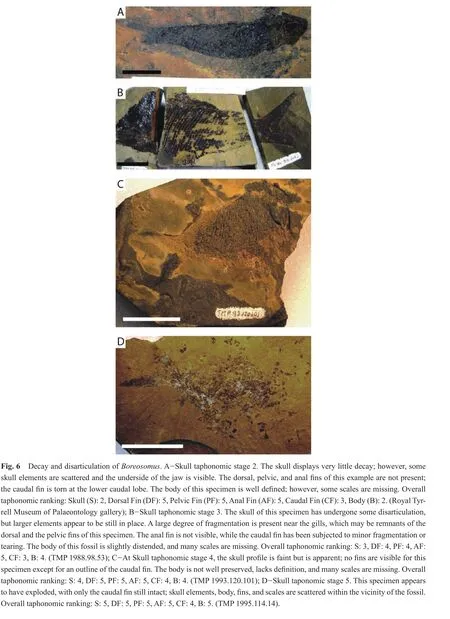

At the early stages of decay of the skull (skull taphonomic stage 2;n= 3), the dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins were not visible in all three specimens; therefore, all fins (excluding the caudal fin)were assigned a taphonomic stage of 5 (Figs.4, 6A; Table 3).The caudal fin was torn in all three specimens (taphonomic stage 3 or 4; 1/3 and 2/3, re-spectively).The body was the best preserved, with specimens evenly distributed between taphonomic stage 2, 3,and 4.

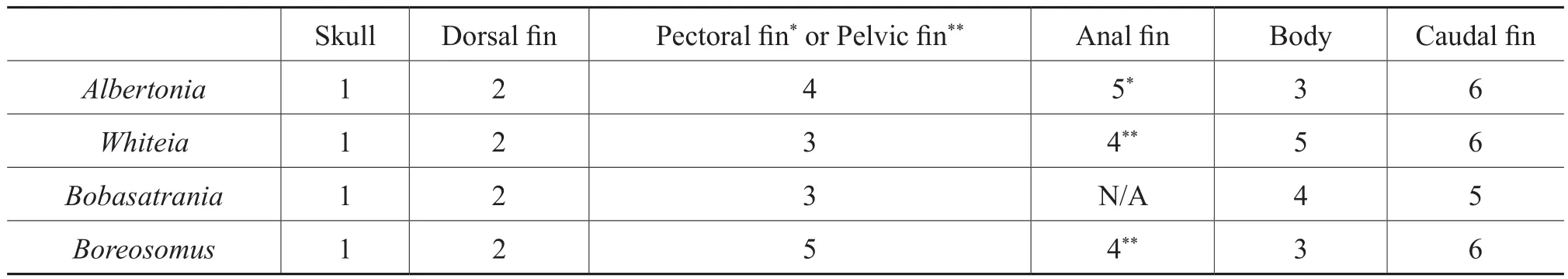

Table 3 Sequence of decay for each of the four studied genera, where 1 = first to exhibit decay after the skull and 6 = last to exhibit decay

At skull taphonomic stage 3 (n= 8), the anal fin was not visible on any of the specimens, resulting in the anal fin of all eight specimens ranked taphonomic stage 5 (Figs.4, 6B; Table 3).Skull taphonomic stage 3 is the only stage where pelvic or dorsal fins were observed.The pelvic fin was fragmented for 2/8 specimens (taphonomic stage 4)and missing from the remainder (6/8)and assigned to taphonomic stage 5.The dorsal fin of 4/8 specimens was fragmented and classif i ed as taphonomic stage 4.The dorsal fin was not observed for 3 specimens (taphonomic stage 5), while one specimen had a dorsal fin with only moderate decay and disarticulation (taphonomic stage 3).The caudal fin and body are the best preserved aspects ofBoreosomusat skull taphonomic stage 3, however, the body exhibited some distortion and bending, and the scales were diff i cult to see.The caudal fin and body are distributed between taphonomic stage 2, 3, or 4, with the majority of specimens within taphonomic stage 3 (4/8 for the caudal fin and 5/8 for the body)and the remainder in taphonomic stage 2(2/8)or 3 (2/8)for the caudal fin and taphonomic stage 3(1/8)or 4 (2/8)for the body.

At skull taphonomic stage 4 (n= 5), no dorsal, pelvic, or anal fins were visible forBoreosomus, and all specimens were ranked at taphonomic stage 5 for these fins (Figs.4,6C; Table 3).The body and caudal fin were slightly better preserved with all samples ranked at taphonomic stage 4:the body was often distorted, some scales were missing and the caudal fin was fragmented but articulated.

When the skull and skull elements were completely disarticulated and scattered at skull taphonomic stage 5(n= 2), the dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins were absent and also assigned to taphonomic stage 5 (Figs.4, 6D; Table 3).At this stage, the body was often bent into a J- or U-shape, with many scales scattered and missing; the body of one specimen was assigned to taphonomic stage 4 and one taphonomic stage 5.The caudal fin, while often folded or torn, was articulated and the best preserved, with both specimens ranked at taphonomic stage 4.

3.2.3Whiteia

A total number of 107 specimens ofWhiteiawere examined and photographed; of those, 23 specimens (22%)were complete and suitable for determining taphonomic stages.The standard length ofWhiteiaexamined for this study ranges from 70 mm to 490 mm.In contrast to the other three genera, coelacanths have two dorsal fins: the anterior or the first dorsal fin (which is not lobed)and the posterior or second (lobed)dorsal fin.In most specimens,each dorsal fin has a similar degree of decay and disarticulation; therefore, the two dorsal fins were assigned a single taphonomic stage ranking.The cosmoid scales for lobefinnedWhiteiaare not as de fined and distinctive as those of the ganoid scales for the ray- finned genera examined for this study.

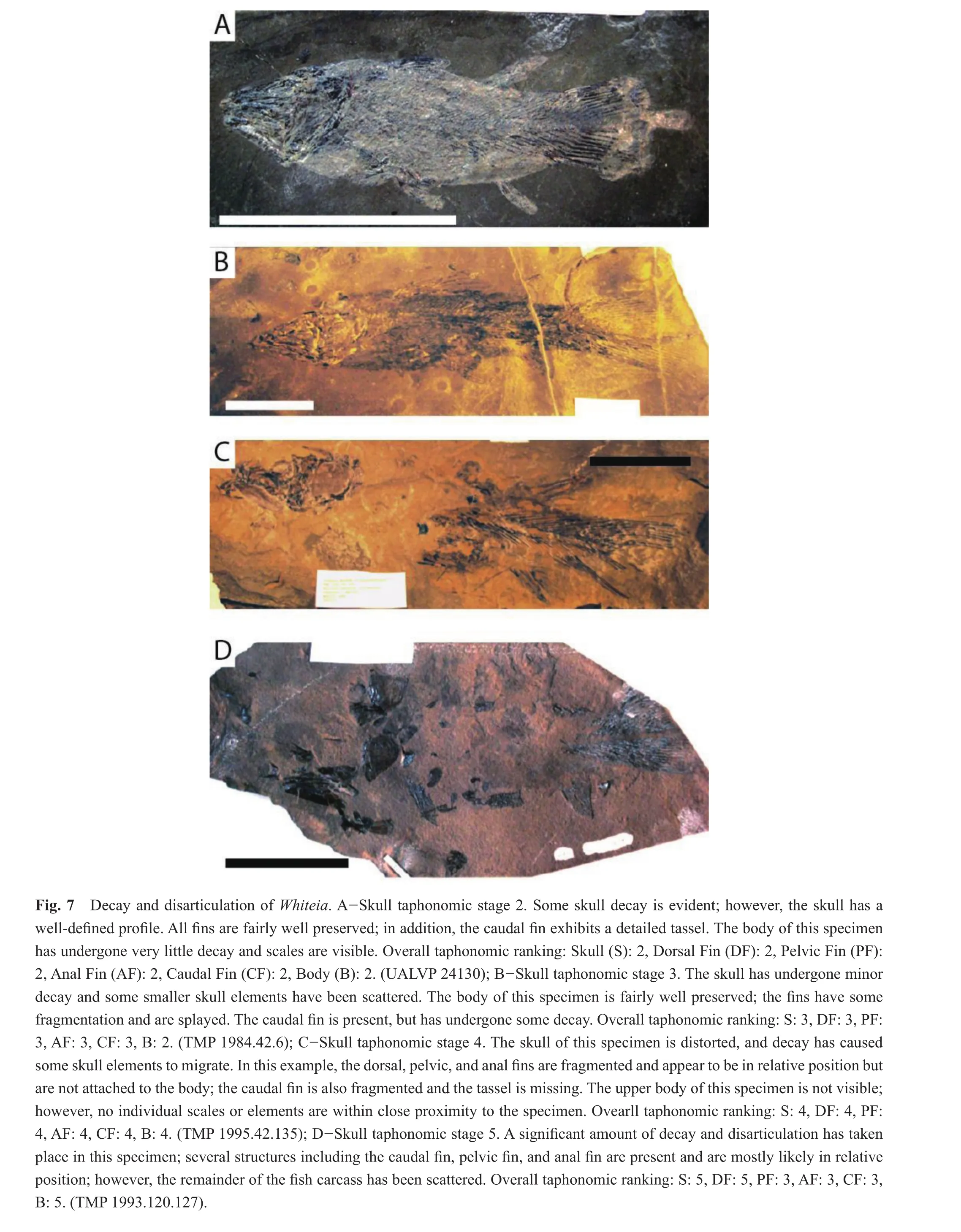

At skull stage 2 (n= 3), the body and dorsal fin were the first to show signs of decay (Figs.4, 7A; Table 3).All specimens (3/3)were ranked at taphonomic stage 2 for the dorsal fin and body, where the dorsal fin exhibited moderate decay and the scales on the body were visible, but not well de fined.The majority of specimens were assigned to taphonomic stage 1 (1/3)or 2 (2/3)for the pelvic, anal, and caudal fins.

At skull stage 3 (n= 9), the dorsal fin, anal fin, and pelvic fin exhibited a slightly greater degree of decay and disarticulation over the body and caudal fin (Figs.4, 7B;Table 3).Over half (5/9, 6/9, 7/9)of the specimens were assigned to taphonomic stage 3 for the dorsal fin, anal fin,and pelvic fin respectively; the remainder of the specimens were ranked taphonomic stage 4 for the dorsal fin (4/9),anal fin (3/9), and pelvic fin (2/9).At skull taphonomic stage 3, the scales were very faint or possibly missing from the body for the majority of specimens.As a result the body of most specimens (7/9)were evaluated as taphonomic stage 3; one specimen exhibited less body decay(taphonomic stage 2), and one more decay (taphonomic stage 4).The caudal fin was the best-preserved feature at skull taphonomic stage 3, with the majority of specimens(8/9)in taphonomic stage 3 and one specimen in taphonomic stage 2.

At the more advanced stage of skull decay, taphonomic stage 4 (n= 9), the fins and body for the majority of specimens are also in taphonomic stage 4 (dorsal fin = 8/9; pelvic fins = 8/9; anal fin = 5/9; caudal fin = 7/9; body = 5/9)(Figs.4, 7C; Table 3).The remainder were ranked within taphonomic stage 3 (2/9 for the caudal fin and body)or taphonomic stage 5 (1/9 for the dorsal fin, anal fin and body; 2/9 for the caudal fin).Overall, the scales were seldom observed and internal structures of the specimens were frequently visible, while the caudal fin was articulated but fragmented.

There were two specimens at taphonomic stage 5 for the skull, where the skull had undergone extensive disarticulation (Figs.4, 7D; Table 3).The body also underwent signi fi cant decomposition, with scales scattered (taphonomic stage 5 for both specimens).The anal, pelvic, and caudal fins were split between taphonomic stage 3 (1/2)or 4 (1/2)and were better preserved than the dorsal fin (1/2 in taphonomic stage 4 and 1/2 in taphonomic stage 5).

3.2.4Bobasatrania

Taphonomic stages forBobasatraniawere assigned for the skull, body, caudal fin, dorsal fin and anal fin; this genus does not have pelvic fins, therefore, determination of taphonomic stages was slightly different than that for the other three genera.The pectoral fin, located behind the gills, is fairly long and extends past the caudal peduncle,but was also not included in this study because it was often pressed flat against the body and obscured by the scales;the other fins were positioned within the surrounding sediment, which provided greater contrast.

A total of 72 specimens ofBobasatraniawere examined and photographed; of those, 32 specimens (44%)were complete and suitable for determining taphonomic stages.Standard length determined by this study ranges from 57 mm to 255 mm, however, larger, incomplete specimens not included in the taphonomic data for this research reached a projected standard length of 570 mm to 1075 mm (in most cases the skull of the larger specimens was missing), and demonstrate the large size of some Early Triassic fishes in the region.The dorsal and anal fins ofBoba?satraniaare very small and appear extended at all times;Bobasatraniaalso had numerous fin rays along the margin of the body (Fig.3D).

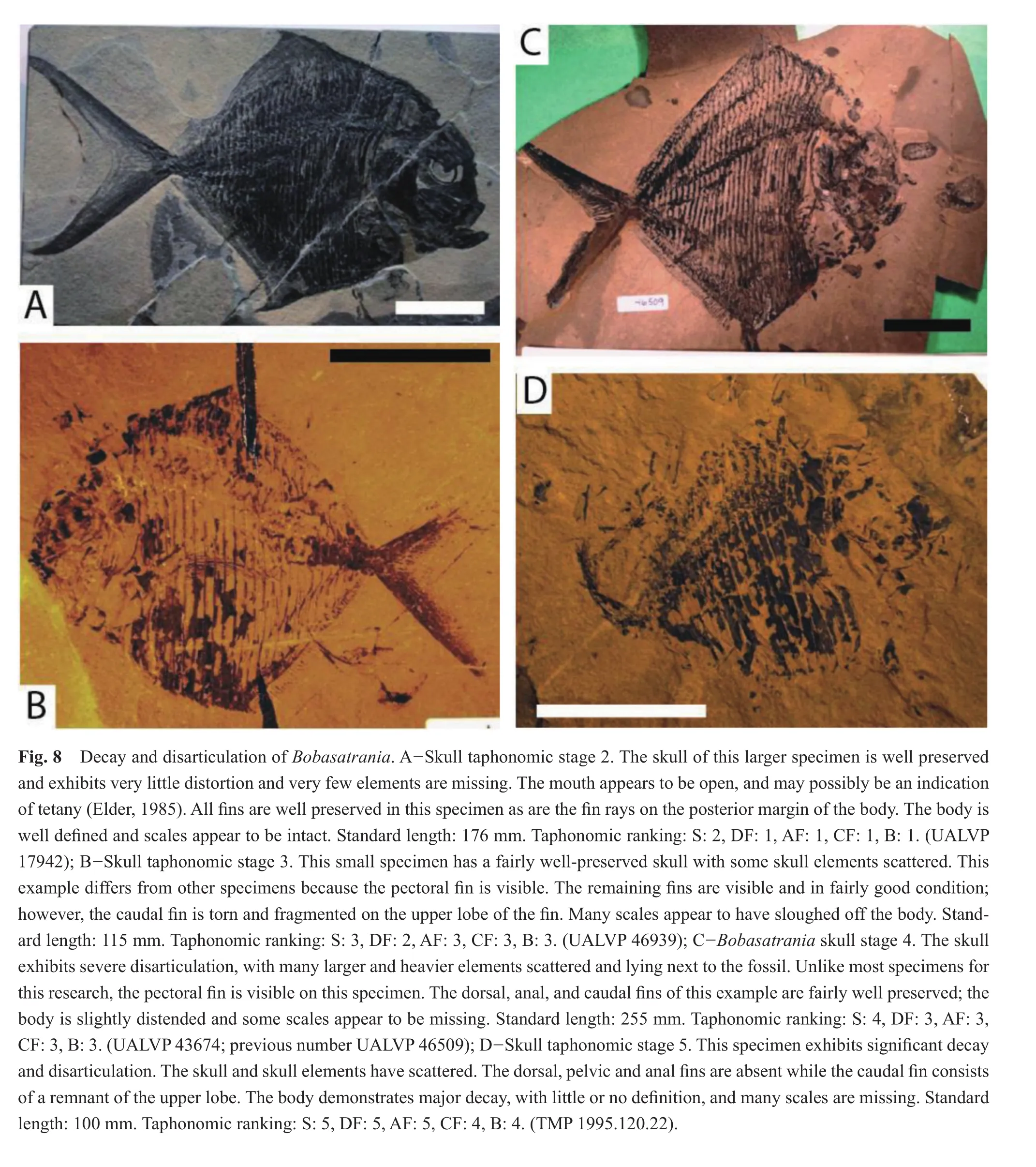

Only two specimens were assigned taphonomic stage 2 for the skull.At this stage, the dorsal and anal fins were the best preserved with both specimens within taphonomic stage 1 (Figs.4, 8A; Table 3).The specimens were split between taphonomic stage 1 and 2 for the body; some of the scales were missing from one specimen.The caudal fin was also divided between taphonomic stage 1 and 3; the caudal fin of one specimen was fragmented.

As skull decay progressed to skull stage 3 (n= 10),the anal fin exhibited the most decay and disarticulation,with the majority of specimens within taphonomic stage 5(3/10), and the remainder in taphonomic stage 3 (3/10)or 4(4/10)(Figs.4, 8B; Table 3).The dorsal fin was distributed between taphonomic stage 2, 3, 4 and 5 (2/10, 3/10, 1/10 and 4/10, respectively).At this stage, the body appears to have lost more scales and the body profile is increasingly distorted, with more than half (6/10)of the specimens within taphonomic stage 4 and the remainder (4/10)within taphonomic stage 3.Overall, the caudal fin appeared to be the best-preserved region, at taphonomic stage 3 (6/10)or 4 (4/10).

At skull taphonomic stage 4 (n= 19), the skull experienced signi fi cantly more decay, with skull elements scattered (Figs.4, 8C; Table 3).The dorsal and anal fins, which are very small fins, are fragmented and fin rays are often dif fi cult to see.The majority of specimens were within taphonomic stage 5 (12/19)for the dorsal fin, with the remainder in taphonomic stage 2 (1/19), 3 (3/19)or 4 (3/19).Most specimens were ranked within taphonomic stage 4(9/19)or 5 (6/19)for the anal fin, with the remainder in taphonomic stage 2 (1/19)or 3 (3/19).The body and caudal fin were assigned taphonomic stage 4 (13/19 for the body and 11/19 for the caudal fin); the body of the remainder of the specimens are ranked within taphonomic stage 2 (1/19)or 3 (5/19), while the caudal fin for the remaining specimens occur within taphonomic stage 2 (2/19), 3(5/19), or 5 (1/19).

Skull taphonomic stage 5, with only one specimen, followed the pattern of previous stages: the small dorsal and anal fins exhibit extensive decay and disarticulation and were assigned taphonomic stage 5 (Figs.4, 8D; Table 3).The body and caudal fin are the best preserved, although they still underwent a great deal of decay and disarticulation and are assessed as taphonomic stage 4.At this skull stage, many scales are missing from the body and the profi le of the body is distorted; nevertheless, the caudal fin and body exhibit a lesser amount of decay and disarticulation, with each assigned to taphonomic stage 4.

3.2.5Fin tetany of Albertonia and Whiteia

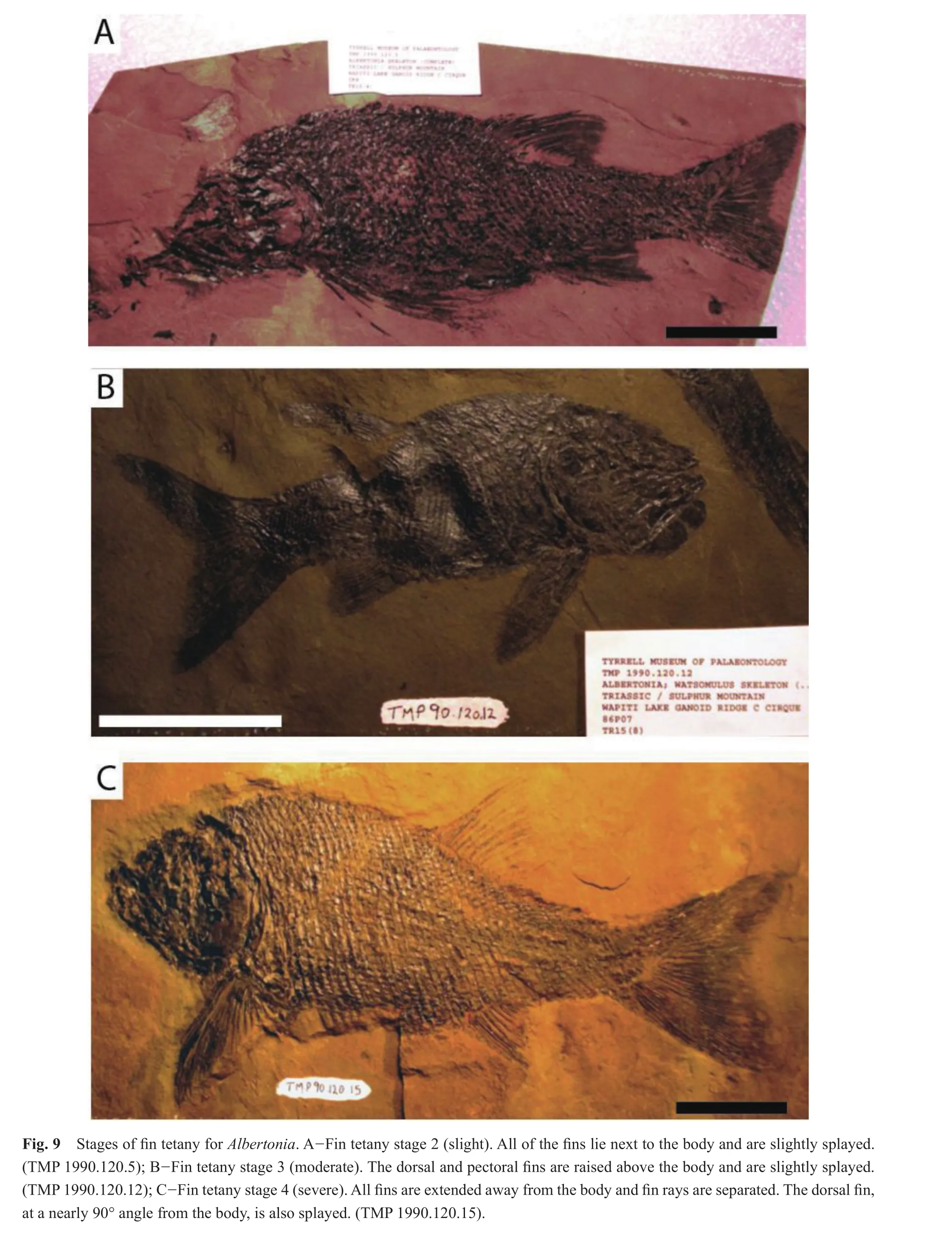

All (n= 67)specimens ofAlbertoniaexhibited tetany of the fins (Table 4); there were no specimens at fin tetany stage 1.The vast majority (61/67)of the specimens were ranked at fin tetany stage 4, severe tetany, where all fins were extended and the fin rays were clearly separated (Fig.9).Five specimens displayed moderate fin tetany at fin tetany stage 3, where one or more of the fins were raised above the body and fin rays were splayed.One specimen showed signs of slight tetany, fin tetany stage 2, where the fins were splayed but not raised above the body.

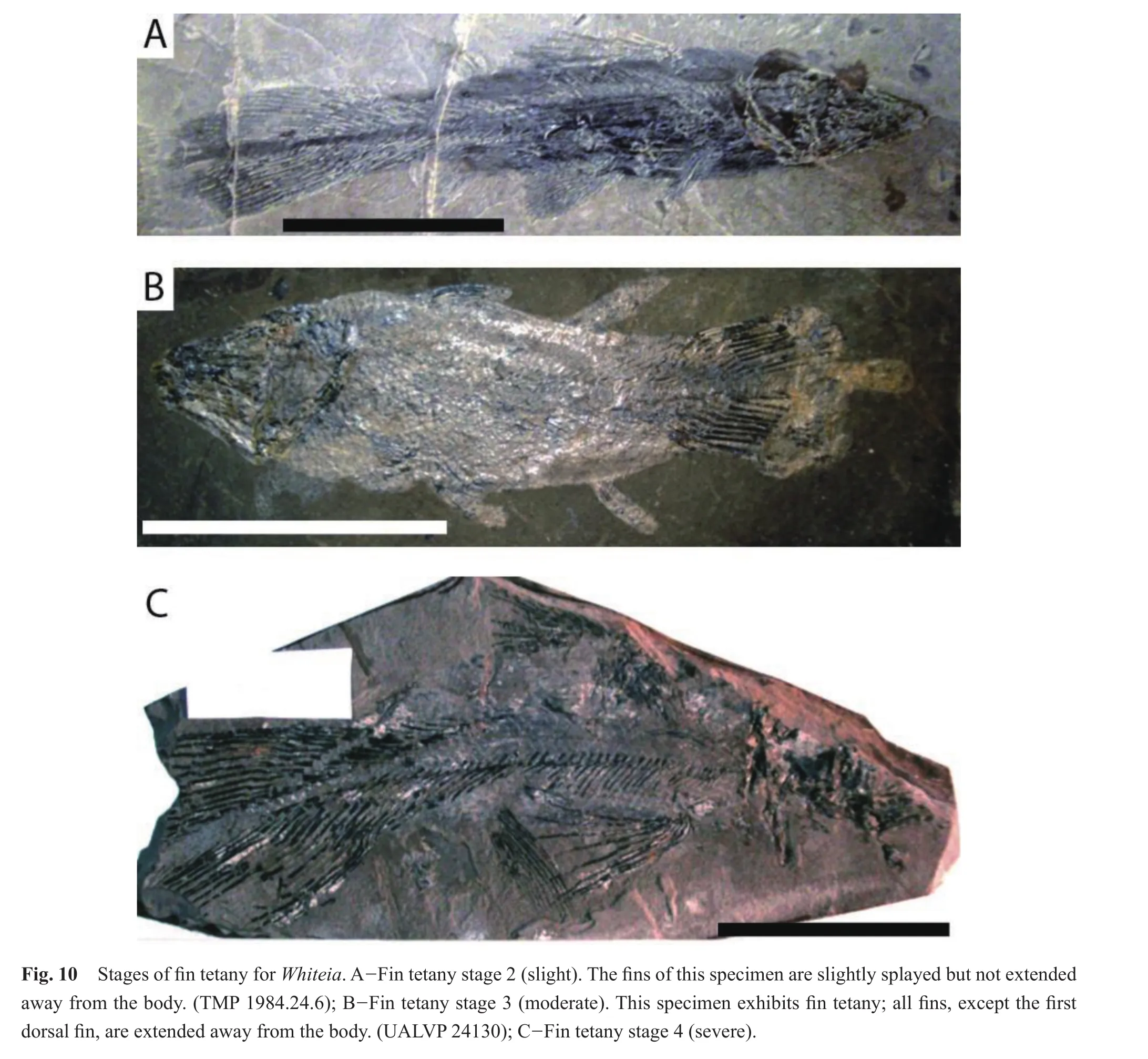

All specimens (n= 32)ofWhiteiaexhibited tetany of the fins (Table 4).There were no specimens at Fin Tetany Stage 1.Over half (18/32)of the specimens exhibited moderate tetany at fin tetany stage 3, where one or more fins were raised above the body and splayed (Fig.10).Nine specimens displayed severe fin tetany, fin tetany stage 4, where the fins were extended away from the body and fully stretched.Five specimens showed signs of slight tetany; the fins were positioned next to the body with one or more fins slightly splayed (fin tetany stage 2).

3.2.6Body tetany of Boreosomus

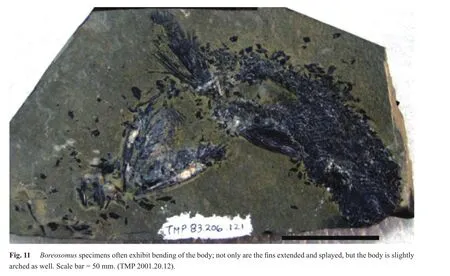

Many of the fossils ofBoreosomusexhibit an arched body that forms a J- or U-shape, a common characteristic of floatation or, less commonly, due to tetany of the body.All 18 specimens ofBoreosomusexamined for taphonomic stages were also examined to determine the orientation of the body (Table 4).The majority ofBoreosomusspecimens (11/18)were flat-lying and did not exhibit arching,or bending of the body, while the remaining seven specimens exhibited bending, arching, or twisting of the body into a J- or U-shape (Fig.11).

Table 4 Tetany results

4 Discussion

4.1 Ambient environmental conditions

Previous studies (e.g., Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith,1988; Wilson and Barton, 1996; Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005)have suggested that articulated and well-preserved fossil fishes imply deposition in environments with (1)high pressures (i.e., deep waters)that suppress the build-up of decay gas; (2)minimal bottom currents to prevent disarticulation and scattering of bones; (3)low oxygen levels to exclude scavengers and slow decay;and (4)cool temperatures that suppress fl oatation.A quiet,deep marine depositional environment is indicated by the fine-grained, clay- and mica-rich matrix that surrounds the specimens, the presence of ammonoid fossils, and the excellent preservation of the fossil fishes with delicate external structures commonly present and frequently articulated (Neuman, 1992; Davieset al., 1997a).Multiple studies have documented anoxic bottom waters in the region at the time the fish were deposited (e.g., Davies, 1997; Davieset al., 1997a, 1997b; Wignall and Twitchett, 2002; Beattyetal., 2008; Zonneveldet al., 2010); anoxic conditions are also supported by the preservation of primary sedimentary structures (ichnofabric index of 1 for all 379 specimens examined for this study)coupled with the lack of evidence of scavenging of the fossil fishes.Anoxic bottom waters are further demonstrated by common fin tetany inWhiteiaandAlbertonia, perhaps as the result of a fatal encounter with oxygen-de fi cient waters.Cold (<15°C), deep (<8-12 m)waters suppress the build up of decay gases and lessen the potential for fl otation of the carcass (Elder, 1985).No evidence of postmortem fl oatation was noted forAlbertonia,Bobasatrania, andWhiteia,suggesting those genera inhabited deeper, colder niches; twisting of the body ofBoreosomusis interpreted as evidence of at least partial fl oatation (see below), suggesting thatBoreosomuslived and died higher in the water column.

4.2 General taphonomic trends in Wapiti Lake fishes

The skull was the first region to show evidence of decay for each of the four fish genera examined, and taphonomic loss proceeded from the anterior to the posterior regions of the fish; this observation has been noted in other, previous studies (e.g., McGrew, 1975; Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988; Wilson and Barton, 1996; Whitmore, 2003;Barton and Wilson, 2005).As the body and fins decayed,the skull underwent further decomposition, eventually resulting in scattering of some of the skull elements and distortion of the pro fi le of the skull.The caudal fin was typically the last region to decay and was still intact even in those specimens where the body had apparently exploded from the buildup of decay gases.

The decay and disarticulation of the dorsal and ventral fins was controlled by the degree of decomposition of the body and abdomen, as well as the size, structure and shape of the fins.Small fins underwent decay, tearing, and fragmentation more rapidly than larger fins.Laboratory experiments conducted by Whitmore (2003)demonstrate that fins are a sensitive indicator of postmortem fl oatation:fins are more likely to lose rigidity, droop, and decay as a response to the length of time the fish fl oated (Whitmore,2003).The caudal fin was typically the last region to decompose, probably because the caudal fin had a strong muscle attachment to the body over a larger area than that for the other fins and the caudal fin was not located near any large cavities (e.g., oral or abdominal cavities)where bacteria could easily in fi ltrate.

The body was better preserved than most of the fins;none of the fishes examined for this study had decayed to the extent where only the skeleton or scattered bones were present.The sturdy ganoid and cosmoid scales were probably the most important factor in the high degree of preservation of the external features of the body; rapid burial also probably played an important role.The specimens examined for this study were often better preserved than fossil fishes from other studies where skeletal remains were the only structures available for study (e.g., McGrew, 1975;Elder, 1985).The ganoid and cosmoid fish of Wapiti Lake therefore provide a useful means to examine the taphonomy marine fish, with the caveat that the heavy, armor-like structure of the scales likely led to better preservation than might be expected otherwise.

5 Paleoecology of Early Triassic fishes

5.1 Albertonia

Albertoniawas a grazer (Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976;Neuman, 1992, 1996)that lived at moderate depths(Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992).Severe tetany of the fins, well-preserved scales, fins, and gills, and a lack of evidence for postmortem f l otation (i.e., no evidence of the body bending or arching into a J- or U-shape),implies thatAlbertoniaperished in deep, oxygen-depleted waters, and probably lived near the oxygen minimum zone(OMZ).

5.2 Boreosomus

The fusiform shape ofBoreosomussuggests the fish was a generalist swimmer that lived higher in the water column thanAlbertonia,BobsatraniaandWhiteia(Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Beltan, 1996; Neuman, 1996; Barbieri and Martin, 2006), and took longer to reach the sea fl oor following death.Many specimens ofBoreosomus(39%)exhibit a body that is bent into a J- or U-shape (Fig.11),which may due to tetany or postmortem fl oatation; the fins ofBoreosomusthat are preservedare not extended or stretched, as would be expected from tetany, and the number of specimens exhibiting bending would be expected to be in the majority if exposure to persistent anoxic conditions were responsibleBoreosomusmortality (Elder,1985; Ferber and Wells, 1995; Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005; Faux and Padian, 2007; Chelloucheet al., 2012).Furthermore, many fins (excluding the caudal fin)were missing completely, suggesting rapid decay and fragmentation in oxygenated waters (Whitmore, 2003).Therefore, arching of the body ofBoreosomusis thought to be due to fl oatation, not tetany.Full fl oatation of the carcass would have likely led to widespread scattering of the remains ofBoreosomus(Sch?fer, 1972); therefore, it seems likely that only the upper body and skull were lifted as decay gas built up, and the fish fell to the sea fl oor with a twisted or arched orientation as gas escaped from the carcass.The heavy ganoid scales prevented the fish caracass from becoming positively buoyant, and led instead to a slow descent to the bottom; interlocking ganoid scales also prevented disarticulation during descent to the seafl oor (Neuman, 1996).

5.3 Whiteia

Whiteiais the only genera examined for this study with a living relative; therefore, predictions can be made aboutWhiteiathrough examination of the modern coelacanth,Latimeria chalumnae, which is not signif i cantly different with respect to outward appearance fromWhiteia.Observations ofLatimeriafrom submersibles demonstrates a passive lifestyle hovering above the seaf l oor in deep ocean waters (e.g., Fricke and Hissmann, 1992).Latimeriacommonly inhabits the subphotic zone with little current activity, low oxygen concentrations, and cold waters with temperatures that range from 15℃ to 19℃ (Hughes and Itazawa, 1972; Fricke and Hissmann, 1990, 2000; Frickeet al., 1991; Forey, 1997; Hissmannet al., 2000).Hughes and Itazawa (1972)conducted experiments on the blood ofLatimeriaand found that oxygen saturation forLatimeriais dependent on low temperatures; the oxygen dissociation curve ofLatimeriablood shows a higher affinity for oxygen at 15℃ than at 28℃, which suggests that it is welladapted to living under deep, cold waters with reduced oxygen levels.Latimeriahas also been observed migrating to depths of 200 m to 400 m (to temperatures as low as 12℃)to feed and to avoid predators (Hissmannet al., 2000).Elder (1985)proposed that 15℃ is the threshold temperature for f l oatation of a fish carcass; 15℃ is the same water temperature thatLatimeriainhabits today (Hissmannet al., 2000).LikeLatimeria,Whiteiamost likely also inhabited deep, cold waters near the OMZ, based on morphologic similarities between the two fish genera, as well as the fine-grained, organic-rich sediments, undisturbed by bioturbation, that surround theWhiteiafossils from Wapiti Lake (Neuman, 1992; Davieset al., 1997a).The OMZ, a stable environment with minimal water currents and cool temperatures, was also an optimal environment for fossil preservation that would minimize f l oatation and transport of a carcass, as well as discourage scavengers and predators.

5.4 Bobasatrania

Bobasatraniawas a large fish with a deep, laterally compressed body that was well suited to a lifestyle in relatively still and quiet waters (Russell, 1951; Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992, 1996).Their crushing teeth suggest they fed on small, slow moving, hard-shelled animals and most likely pursued a lifestyle of limited activity, grazing in quiet waters near the seaf l oor (Neuman,1992, 1996).Bobasatraniaalso had well-developed and thick ganoid scales, which more than likely madeBoba?satraniaa fairly heavy fish.IfBobasatraniaventured into deeper, suboxic waters the combination of oxygen-depleted waters and the weight of the heavy ganoid scales may have made it diff i cult for the fish to escape.Overall, the well-preserved nature ofBobasatraniacoupled with an interpreted lifestyle in deep, quiet waters (Russell, 1951;Schaeffer and Mangus, 1976; Neuman, 1992, 1996), suggests that it also lived near the OMZ.

6 Conclusions

The current study examined four genera of well-preserved, Early Triassic fossil marine fishes from the Wapiti Lake locality of the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member of the Sulphur Mountain Formation, in British Columbia, Canada.The diverse community of fishes and other organisms,including marine reptiles, ichthyosaurs, phyllocarids, brachiopods, bivalves, ammonoids and conodonts was likely a good representation of the organisms living in the region at the time.The following conclusions are made concerning these fossil fishes and their taphonomy:

1)Each of the genera examined for this study sustained some level of decay and disarticulation that was initiated within the skull and progressed from the anterior to the posterior region of the fish fossil; this phenomenon has been documented by many other studies (McGrew, 1975;Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988; Wilson and Barton,1996; Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005).

2)The lifestyle and niche that each of the four genera occupied was an important factor in determining the level of preservation.Those fishes living close to the OMZ(Albertonia,WhiteiaandBobasatrania)had a shorter distance from death to burial and were better preserved,which is supported by taphonomic and tetany data.Alternatively, those fishes living farther from the OMZ, most likely in warmer, oxygenated waters, underwent greater taphonomic loss: indeed,Boreosomusexhibits ample evidence of arched bodies due to postmortem fl oatation, more fin fragmentation, and greater degree of taphonomic loss thanAlbertonia,WhiteiaandBobasatrania, which lived closer to the OMZ.

3)The four fish genera are well preserved because they were deposited in deep, cold waters under anoxic conditions.These results support previous studies that suggest that widespread bottom water anoxia persisted in the region during the Early Triassic (e.g., Davies, 1997; Davieset al., 1997a, 1997b; Wignall and Twitchett, 2002; Beattyet al., 2008; Zonneveldet al., 2010).

4)The four fish genera are also well-preserved because of the dermal covering of the fish; the ganoid scales forAlbertonia, BobasatraniaandBoreosomus, and cosmoid scales forWhiteiaprovided a protective outer covering that limited the amount of disarticulation and scattering and increased the preservation potential of fish that possessed these scales.Therefore, the results of this study are somewhat constrained to fish with similar tough, outer dermal coverings that limited decay and disarticulation of the fish, however, the comparable sequence of head to tail decay between this study and other studies (McGrew, 1975;Elder, 1985; Elder and Smith, 1988; Wilson and Barton,1996; Whitmore, 2003; Barton and Wilson, 2005)is signi fi cant, as is the similarity with respect to the early loss of fins other than the caudal fin (Whitmore, 2003).Therefore this study has applications beyond ganoid and cosmoid fishes in that it suggests that the taphonomic processes acting on lacustrine and marine fish are similar with respect to decay and disarticulation, and suggests that many of the observations about lacustrine fish taphonomy are also applicable to marine fish.

Fricke and Hissmann (2000)suggest that the radiation of modern actinopterygian fishes forced coelacanths of the past into deeper and oxygen-def i cient waters.Many “l(fā)iving fossils” formerly inhabited shelf environments and retreated into deeper waters, possibly in order to reduce their vulnerability to more advanced predators (e.g., Bottjer and Jablonski, 1988).The results of the current study suggest that coelacanths were already exiled to deep, oxygen-def icient environments by the beginning of the Mesozoic Era.

There have been few studies of the taphonomy of marine fishes prior to the research presented here.While the anatomical and physiological characteristics of modern fishes will likely continue to inhibit marine taphonomy studies, examination of ancient fish, particularly those with ganoid or cosmoid scales, may provide future avenues of research to gain a better understanding of marine fish taphonomy and provide a powerful tool to examine ancient fish behavior and their ecology.

Asano, Y.T., Hirao, K., Tanaka, Y., 2012.Taphonomy of fish fossils from the Miocene Tottori Group, southwest Japan; Part 1, Stratigraphy and geologic structure.Earth Science (Chikyu Kagaku),66: 5-16.

Barbieri, L., Martin, M., 2006.Swimming patterns of Malagasy Triassic fishes and environment Geological Society of Denmark.DGF Online Series, 1: 1-2.

Barton, D.G., Wilson, M.V.H., 2005.Taphonomic variations in Eocene fish-bearing varves at Horsef l y, British Columbia, reveal 10,000 years of environmental change.Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 42: 137-149.

Baughman, J.L., 1947.Loss of fish due to freeze.Texas Game and Fish, 5: 12-13.

Beatty, T.W., Zonneveld, J.-P., Henderson, C., 2008.Anomalously diverse Early Triassic ichnofossil assemblages in northwest Pangea: A case for a shallow-marine habitable zone.Geology, 36:771-774.

Behrensmeyer, A.K., Kidwell, S.M., 1985.Taphonomy’s contributions to paleobiology.Paleobiology, 11: 105-119.

Beltan, L., 1996.Overview of the systematics, paleobiology, and paleoecology of Triassic fishes of northwestern Madagascar.In:Arratia, G., Viohl, G., (eds).Mesozoic Fishes-Systematics and Paleoecology Munchen, Verlag Dr.Friedrich Pfeil, 479-500.

Bieńkowska, M., 2004.Taphonomy of ichthyofauna from an Oligocene sequence (Tylawa Limestones horizon)of the Outer Carpathians, Poland.Geological Quarterly, 48: 181-192.

Bieńkowska, M., 2008.Captivating examples of Oligocene fishtaphocoenoses from the Polish Outer Carpathians.In: Krempaská, Z., (ed).6thMeeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists.Spi?ská Nová Ves - Slovak Republic,17-21.

Bieńkowska-Wasiluk, M., 2010.Taphonomy of Oligocene teleost fishes from the Outer Carpathians of Poland.Acta Geologica Polonica, 60: 479-533.

Bottjer, D.J., Jablonski, D., 1988.Paleoenvironmental patterns in the evolution of Post-Paleozoic benthic marine invertebrates.Palaios, 3: 540-560.

Brett, C.E., Baird, G.C., 1986.Comparative taphonomy: A key to paleoenvironmental interpretationbased on fossil preservation.Palaios, 1: 207-227.

Brinkman, D., 1988.A weigeltisaurid reptile from the Lower Triassic of British Columbia.Palaeontology, 31: 951-955.

Britton, D.R., 1988.The occurrence of fish remains in modern lake systems: A test of the strati fi ed-lake model.[M.S.Thesis]: Loma Linda University, 315.

Brongersma-Sanders, M., 1957.Mass mortality in the sea.In: Hedgpeth, J.W., (ed).Treatise on Marine Ecology and Paleoecology,I: Boulder, CO USA.Geological Society of America Memoirs,67: 941-1010.

Burrow, C.J., 1996.Taphonomy of acanthodians from the Devonian Bunga Beds (Late Givetian/Early Frasnian)of New South Wales.Historical Biology, 11: 213-228.

Callaway, J.M., Brinkman, D.B., 1989.Ichthyosaurs (Reptilia, Ichthyosauria)from the Lower and Middle Triassic Sulphur Mountain Formation, Wapiti Lake Area, British Columbia, Canada.Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 26: 1491-1500.

Capriles, J.M., Domic, A.I., Moore, K.M., 2008.Fish remains from the Formative Period (1000 BC-AD 400)of Lake Titicaca, Bolivia: Zooarchaeology and taphonomy.Quaternary International,180: 115-126.

Carnevale, G., Landini, W., Ragaini, L., Di Celma, C., Cantalamessa,G., 2011.Taphonomic and paleoecological analyses (mollusks and fishes)of the Súa Member condensed shellbed, upper Onzole Formation (Early Pliocene, Ecuador).Palaios, 26: 160-172.

Chellouche, P., Fürsich, F.T., Mauser, M., 2012.Taphonomy of neopterygian fishes from the Upper Kimmeridgian Wattendorf Plattenkalk of Southern Germany.Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 92: 99-117.

Chow, H., Liu, H., 1957.Fossil fishes from Huanshan, Shensi.Acta Palaeontogica Sinica, 5: 295-305.

Cloutier, R., Proust, J.-N., Bernadette, T., 2011.The Miguasha Fossil-Fish-Lagerstatte: A consequence of the Devonian landsea interactions.Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 91:293-323.

Davies, G.R., 1997.The Triassic of the western Canada sedimentary basin; tectonic and stratigraphic framework, paleogeography,paleoclimate and biota.Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, 45(4): 434-460.

Davies, G.R., Moslow, T.F., Sherwin, M.D., 1997a.Ganoid fish Albertonia sp.from the Lower Triassic Montney Formation, Western Canada.Sedimentary Basin Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, 45(4): 715-718.

Davies, G.R., Moslow, T.F., Sherwin, M.D., 1997b.The Lower Triassic Montney Formation, west-central Alberta.Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, 45(4): 474-505.

Donaldson, M.R., Cooke, S.J., Patterson, D.A., MacDonald, J.S.,2008.Cold shock and fish Journal of Fish Biology, 73: 1491-1530.

Droser, M.L., Bottjer, D.J., 1986.A semiquantitative fi eld classifi cation of ichnofabric.Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 56:558-559.

Efremov, I.A., 1940.Taphonomy: A new branch of paleontology.Pan-American Geologist, 74: 81-93.

Elder, R.L., 1985.Principles of aquatic taphonomy with examples from the fossil record [PhD.Thesis]: University of Michigan,336.

Elder, R.L., Smith, G.R., 1988.Environmental interpretation of burial and preservation of Clarkia fishes.In: Smiley, C.J., (ed).Late Cenozoic History of the Paci fi c Northwest: San Francisco,CA, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Paci fi c Division, 85-94.

Faux, C.M., Padian, K., 2007.The opisthotonic posture of vertebrate skeletons: Postmortem contraction or death throes? Paleobiology, 33: 201-226.

Ferber, C.T., Wells, N.A., 1995.Paleolimnology and taphonomy of some fish deposits in “Fossil’’ and “Uinta’’ Lakes of the Eocene Green River Formation, Utah and Wyoming.Palaeogeography,Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 117: 185-210.

Fernandez-Jalvo, Y., 1995.Small mammal taphonomy at La Trinchera De Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain)— A remarkable example of taphonomic criteria used for stratigraphic correlations and Paleoenvironment Interpretations.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 114: 167-195.

Forey, P.L., 1997.History of Coelacanth Fishes.New York, Springer.

Fricke, H., Hissmann, K., 1990.Natural habitat of coelacanths.Nature, 346(6282): 323-324.

Fricke, H., Hissmann, K., 1992.Locomotion, fin coordination and body form of the living coelacanthLatimeria chalumnae.Environmental Biology of Fishes, 34(4): 329-356.

Fricke, H., Hissmann, K., 2000.Feeding ecology and evolutionary survival of the living coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae.Marine Biology, 136(2): 379-386.

Fricke, H., Hissmann, K., Schauer, J., Reinicke, O., Kasang, L.,Plante, R., 1991.Habitat and population-size of the coelacanthLatimeria chalumnaeat Grand Comoro.Environmental Biology of Fishes, 32(1-4): 287-300.

Fürsich, F.T., Werner, W., Schneider, S., M?user, M., 2007.Sedimentology, taphonomy, and palaeoecology of a laminated plattenkalk from the Kimmeridgian of the northern Franconian Alb(southern Germany).Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 243: 92-117.

Gibson, D.W., 1972.Triassic stratigraphy of the Pine Pass - Smoky River area, Rocky Mountain Foothills and Front Ranges of British Columbia and Alberta, Ottawa, Canada.Geological Survey of Canada, Paper, 71-30, 108.

Gibson, D.W., 1975.Triassic rocks of the Rocky Mountain foothills and front ranges of northeastern British Columbia and westcentral Alberta, Ottawa, ON.Geological Survey of Canada, 42.

Gilmore, R.G., Bullock, L.H., Berry, F.H., 1978.Hypothermal mortality in marine fishes of south-central Florida, January, 1977.Northeast Gulf Science, 2: 77-97.

Gunter, G., 1941.Death of fishes due to cold on the Texas coast,January, 1940.Ecology, 22: 203-208.

Gunter, G., 1942.Offatts Bayou, a locality with recurrent summer mortality of marine organisms.American Midland Naturalist, 28:631-633.

Gunter, G., 1947.Catastrophism in the sea and its paleontological signif i cance, with special reference to the Gulf of Mexico.American Journal of Science, 245: 669-676.

Hankin, D.G., McCanne, D., 2000.Estimating the number of fish and crayfish killed and the proportions of wild and hatchery rainbow trout in the Cantara spill.California Fish and Game, 86:4-20.

Hissmann, K., Fricke, H., Schauer, J., 2000.Patterns of time and space utilisation in coelacanths (Latimeria chalumnae), determined by ultrasonic telemetry.Marine Biology, 136(5): 943-952.

Histon, K., 2012.Paleoenvironmental and temporal signif i cance of variably colored Paleozoic orthoconic nautiloid cephalopod accumulations.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 367-368: 193-208.

Hughes, G.M., Itazawa, Y., 1972.The effect of temperature on the respiratory function of coelacanth blood.Experientia, 28: 1247.

Lehman, J.-P., Chateau, C., Laurain, M., Nauche, M., 1959.Paléontologie de Madagascar.XXVIII.Les Poissons de la Sakamena moyenne.Annales de paléontologie, 45: 177-219.

Luk?evi?s, E., Ahlberg, P.E., Stinkulis, ?., Je?ena, V., Zupi??, I.,2011.Frasnian vertebrate taphonomy and sedimentology of macrofossil concentrations from the Langsēde Cliff, Latvia.Lethaia,45: 356-370.

Malenda, H., Wilk, J.L., Fillmore, D.L., Heness, E.A., Kraal, E.R., Simpson, E.L., Hartline, B.W., Szajna, M.J., 2012.Taphonomy of lacustrine shoreline fish-part conglomerates in the Late Triassic Age Lockatong Formation (Collegeville, Pennsylvania,USA): Toward the recognition of catastrophic fish kills in the rock record.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 313-314: 234-245.

Mancuso, A.C., 2012, Taphonomic analysis of fish in rift lacustrine systems: Environmental indicators and implications for fish speciation.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,339-341: 121-131.

Mapes, R.H., Landman, N.H., Cochran, K., Goiran, C., de Forges,B.R., Renfro, A., 2010.Early Taphonomy and Signif i cance of Naturally Submerged Nautilus Shells from the New Caledonia Region.Palaios, 25: 597-610.

Martin-Closas, C., Gomez, B., 2004.Plant taphonomy and palaeoecological interpretations: A Synthesis.Geobios, 37: 65-88.

McDonald, H.G., Dundas, R.G., Chatters, J.C., 2013.Taxonomy,paleoecology and taphonomy of Ground Sloths (Xenarthra)from the Fairmead Landf i ll Locality (Pleistocene, Irvingtonian)of Madera County, California.Quaternary Research, 79: 215-227.

McGrew, P.O., 1975.Taphonomy of Eocene Fish from Fossil Basin,Wyoming: Fieldiana.Geology, 33: 257-270.

Minshall, G.W., Hitchcock, E., Barnes, J.R., 1991.Decomposition of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)carcasses in a forest stream ecosystem inhabited only by nonanadromous fish populations.Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 48:191-195.

Moy-Thomas, J.A., 1935.The coelacanth fishes from Madagascar.Geological Magazine, 72: 213-227.

Mutter, R.J., Neuman, A.G., 2009.Recovery from the end-Permian extinction event: Evidence from “LilliputListracanthus”.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 284: 22-28.

Neuman, A.G., 1992.Lower and Middle Triassic Sulphur Mountain Formation Wapiti Lake, British Columbia.Summary of Geology and Fauna Contributions to Natural Science, Royal British Columbia Provincial Museum, 16: 1-12.

Neuman, A.G., 1996.Fishes of the Triassic — Trawling off Pangea,life in stone: A natural history of British Columbia’s Fossils.Vancouver, UBC Press, 105-115.

Nielsen, E., 1942.Studies on the Triassic fishes from East Greenland,Part I.GlaucolepisandBoreosomus, Copenhagen, C.A.Reitzels Forlag, 403.

Nielsen, E., 1952.A preliminary note onBobasatrania groenlandica.Communications paléontologiques/Museum de minéralogie et de géologie de l’Université de Copenhague, 12: 197-204.

Orchard, M.J., Zonneveld, J.-P., 2009.The Lower Triassic Sulphur Mountain Formation in the Wapiti Lake area: Lithostratigraphy,conodont biostratigraphy, and a new biozonation for the lower Olenekian (Smithian).Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 46:757-790.

Parker, R.O., 1970.Surfacing of dead fish following application of rotenone.Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 99:805-807.

Patton, W.W., Tailleur, I.L., 1964.Geology of the Killik-Itkillik region, Alaska.Part 3.Areal geology.USGS Professional Paper,303: 409-500.

Peterson, J.E., Bigalke, C.L., 2013.Hydrodynamic behaviors of Pachycephalosaurid Domes in controlled f l uvial settings: A case study in experimental dinosaur taphonomy.Palaios, 28: 285-292.

Russell, L.S., 1951.Bobasatrania? canadensis(Lambe), a giant chondrostean fish from the Rocky Mountains.Bulletin of the National Museum of Canada, 123: 218-224.

Sansom, R.S., 2013.Atlas of vertebrate decay; a visual and taphonomic guide to fossil interpretation.Palaeontology, 56: 457-474.

Schaeffer, B., Mangus, M., 1976.An Early Triassic fish assemblage from British Columbia.Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 156: 517-563.

Sch?fer, W., 1972.Ecology and palaeoecology of marine environments, Chicago.University of Chicago Press, 568.

Smith, J.W., 1999.A large fish kill of Atlantic menhaden,Brevoortia tyrannus, on the North Carolina coast.The Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientif i c Society, 115: 157-163.

Sorensen, A.M., Surlyk, F., 2013.Mollusc life and death assemblages on a tropical rocky shore as proxies for the taphonomic loss in a fossil counterpart.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology,Palaeoecology, 377: 1-12.

Stensi?, E.A., 1921.Triassic Fishes from Spitzbergen, Part I, Vienna, Holzhausern, 307.

Stensi?, E.A., 1932.Triassic fishes from East Greenland: Meddel.Gr?nland, 83: 88-90.

Tintori, A., 1992.Fish taphonomy and Triassic anoxic basins from the Alps: A case history.Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigraf i a, 97: 393-408.

Vasi?kova, J., Luk?evi?s, E., Stinkulis, ?., Zupi??, I., 2012.Taphonomy of the vertebrate bone beds from the Klūnas fossil site, Upper Devonian Tērvete Formation of Latvia (Estonian).Journal of Earth Sciences, 61: 105-119.

Vía Boada, L., Villalta, J.F., Cerdá, M.E., 1977.Paleontologia y paleoecolgia de los yacimientos fosiliferos del Muschelkalk superior entre Alcover y Mont-Ral (Monta?as de Prades, Provincia de Tarragona).Cuadernos Geología Ibérica, 4: 247-256.

Vullo, R., Cavin, L., Clochard, V., 2009.An ammonite-fish association from the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic)of La Rochelle,western France.Lethaia, 42: 462-468.

Weigelt, J., 1989.Recent vertebrate carcasses and their paleobiological implications, Chicago, IL USA.University of Chicago Press,188.

Whitmore, J.H., 2003.Experimental fish taphonomy with a comparison to fossil fishes [PhD.Thesis]: Loma Linda University, 327.

Wignall, P.B., Twitchett, R.J., 2002.Extent, duration, and nature of the Permian-Triassic superanoxic event.In: Koeberl, C., MacLeod, K.C., (eds).Catastrophic events and mass extinctions:Impacts and beyond.Boulder, CO, Geological Society of America Special Paper, 356: 395-413.

Wilson, M.V.H., Barton, D.G., 1996.Seven centuries of taphonomic variation in Eocene freshwater fishes preserved in varves:Paleoenvironments and temporal averaging.Paleobiology, 22:535-542.

Zonneveld, J.-P., MacNaughton, R.B., Utting, J., Beatty, T.W.,Pemberton, S.G., Henderson, C.M., 2010.Sedimentology and ichnology of the Lower Triassic Montney Formation in the Pedigree-Ring/Border-Kahntah River area, northwestern Alberta and northeastern British Columbia.Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, 58: 115-140.

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年4期

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年4期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Deformed stromatolites in marbles of the Mesoproterozoic Wumishan Formation as evidence for synsedimentary seismic activity

- Late Quaternary palaeoenvironmental changes documented by microfaunas and shell stable isotopes in the southern Pearl River Delta plain,South China

- Three abrupt climatic events since the Late Pleistocene in the North China Plain

- Geochemistry of the Late Paleozoic cherts in the Youjiang Basin: Implications for the basin evolution

- Milankovitch-driven cycles in the Precambrian of China: The Wumishan Formation

- Pliocene taxodiaceous fossil wood from southwestern Ukraine and its palaeoenvironmental implications