The palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres

Spencer G.Lucas

New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Road N.W., Albuquerque, New Mexico 87104-1375, USA

1 Introduction*

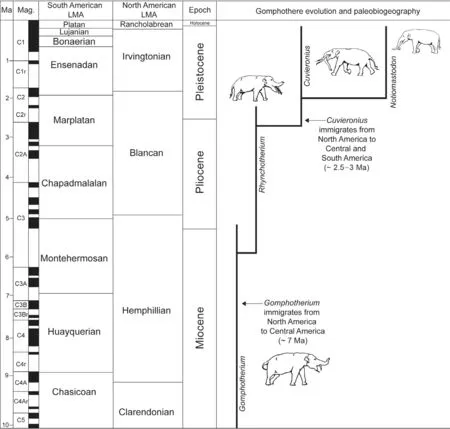

During the Late Pliocene, about 3 Ma, the Panamanian isthmus closed, joining North and South America by a dryland connection for the first time since the Jurassic.What ensued is one of the most significant and written about palaeobiogeographic events in mammalian history—the“Great American Biotic Interchange” (GABI)(e.g., Woodburne, 2010).Mammals immigrated from North America to South America and vice versa, fundamentally altering the Pleistocene to recent mammalian faunas of the New World continents.One of the most important mammalian groups that participated in the GABI were the Probos-cidea, the elephants and their allies.

The Proboscidea had entered North America from Eurasia during the Middle Miocene, about 16 Ma (Prothero and Dold, 2008; Protheroet al., 2008).Once in the New World, gomphotheres rapidly spread across North America so that their Miocene fossils are found from western Canada to Florida and in Mexico as far south as Oaxaca(Lambert and Shoshani, 1998).The oldest Central American gomphothere records, in Guatemala, Honduras and Costa Rica, are Late Miocene in age, about 7 Ma (Lucas and Alvarado, 2010).

The appearance of proboscideans in South America is now a subject of lively discussion.Traditionally, proboscideans were believed to have entered South America only after closure of the Panamanian isthmus.Indeed, the oldest well-dated proboscidean fossil from South America postdates that closure; it is from Argentina and is ~ 2.5 Ma (Regueroet al., 2007).All but one South American proboscidean fossil are evidently younger than that.The exception is a single gomphothere fossil from Peru, namedAmahuacatherium peruviumand claimed to be older than 9 Ma (Fraileyet al., 1996; Romero-Pittman, 1996; Campbellet al., 2000, 2001, 2009, 2010).If correctly dated, this fossil indicates an older, Miocene entry of gomphotheres into South America.

Further fuel for controversy about the entry of gomphotheres into South America stems from different views of the alpha taxonomy and evolutionary history (phylogenetic relationships)of South American gomphotheres.One view sees a small group of South American taxa, all descended from a single immigrant, whereas another sees two different taxa that represent two separate immigrations.

My goal here is to review this controversy over the palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres.In so doing, I critically assess the alpha taxonomy, age dating and phylogenetic relationships of South American gomphotheres.I conclude that the best data and most supportable inferences indicate a single immigration of gomphotheres into South America after Pliocene closure of the Panamanian isthmus that led to a modest, endemic evolutionary radiation of gomphotheres in the South American Neotropics.

2 History of the problem

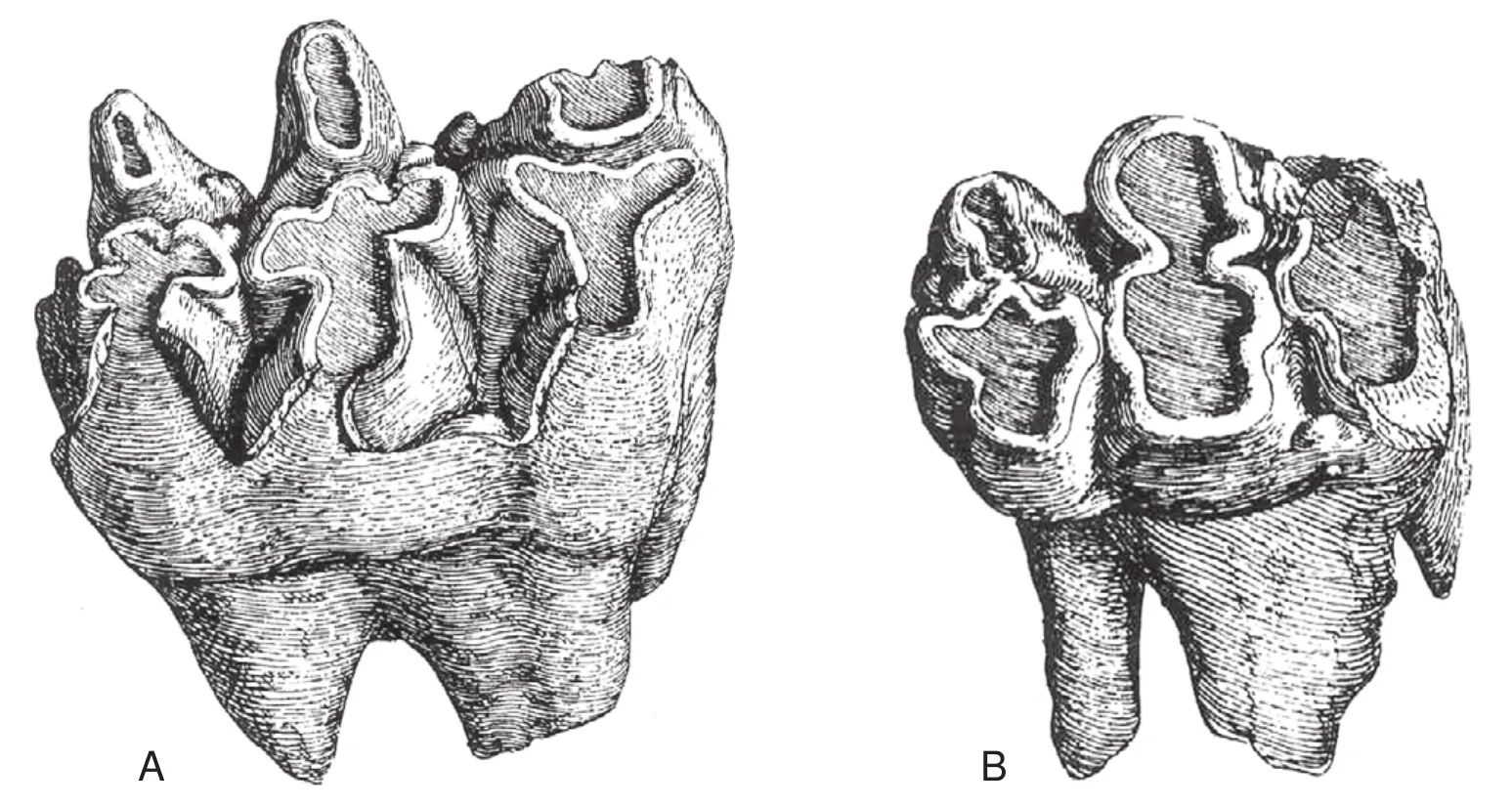

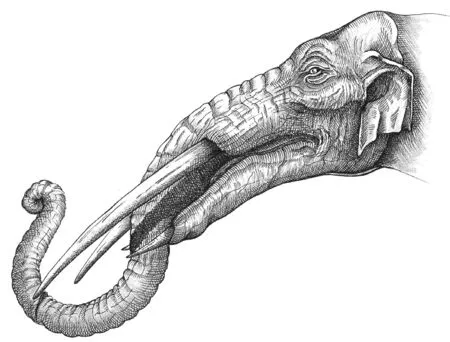

The scientific study of South American gomphotheres is as old as the science of vertebrate palaeontology itself,and began with the legendary South American expedition of German renaissance man Alexander von Humboldt(1769-1859).Humboldt brought two proboscidean teeth back to Europe, which he gave to French savant Georges Cuvier (1769-1832), who many regard as the first vertebrate palaeontologist.Cuvier (1806)described and illustrated these teeth (Fig.1), and based on his work they were soon assigned to separate species, asMastodon andiumandMastodon humboldtii.What followed was a century of diverse discoveries of proboscidean fossils in South America, notably in Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador and Argen-tina (Osborn, 1936, pp.515-537, provides a detailed historical review).

Fig.1 Cuvier’s (1806)illustrations of the teeth of the “mastodonte des cordillères” (A-Later called Mastodon andium)and the “mastodonte humboldien” (B-Later called Mastodon humboldtii).The tooth in A is a left m2, and the tooth in B is an incomplete m1 or dp4.Alexander von Humboldt collected the tooth in A from Ecuador (from the volcano of Imbabura near Quito), and he collected the tooth in B in Chile.

The classic monograph on the fossil mammals from Tarija, Bolivia, by Boule and Thevenin (1920), well reflected approximately 100 years of taxonomic thought about the South American gomphotheres.All were regarded as “mastodonts” (a term that included what are now referred to as gomphotheres)and generally assigned to two species of the genusMastodon.Joleaud (1939, pl.89 and accompanying text)envisioned these “mastodonts” as having immigrated in South America during the “Middle Pliocene.”

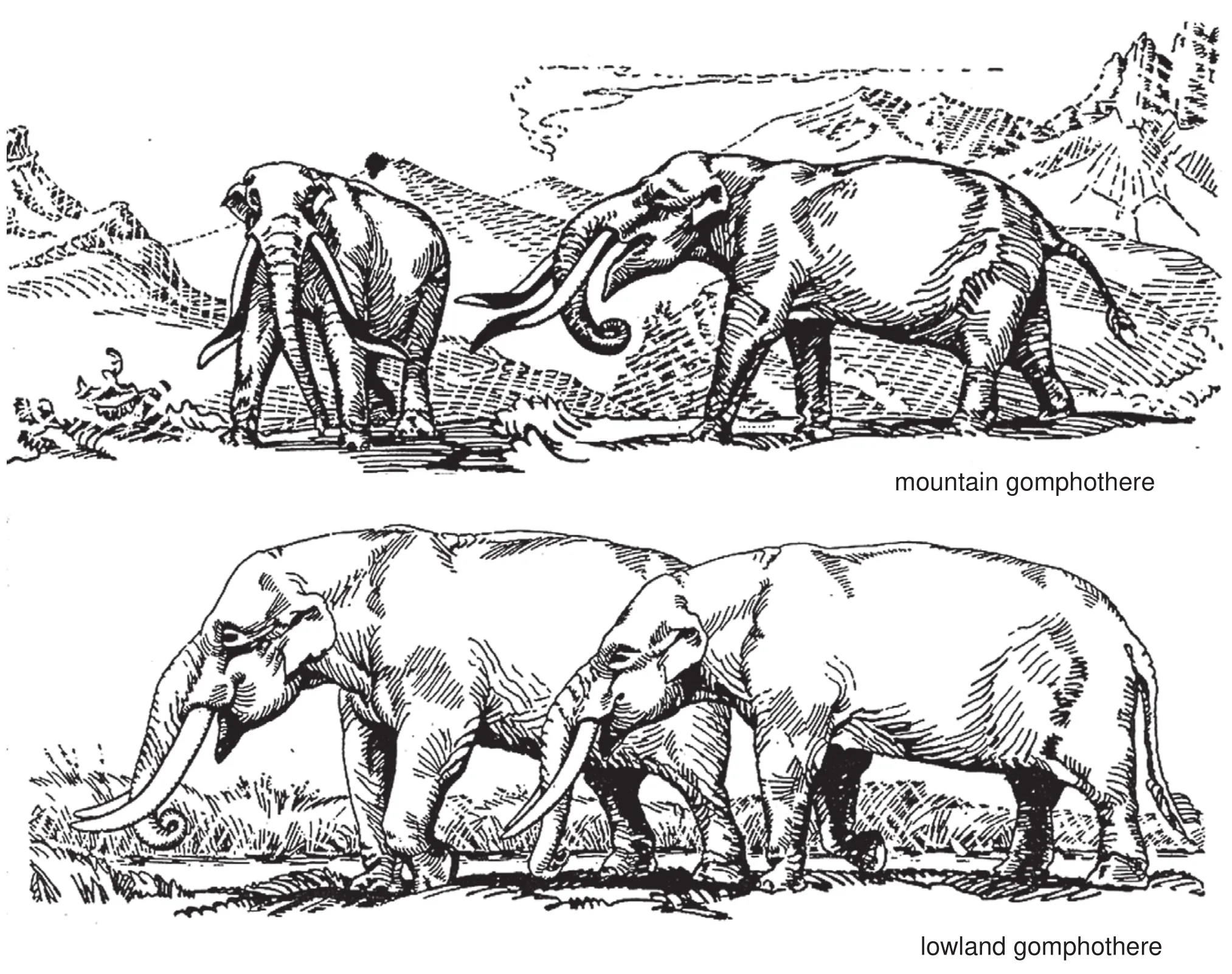

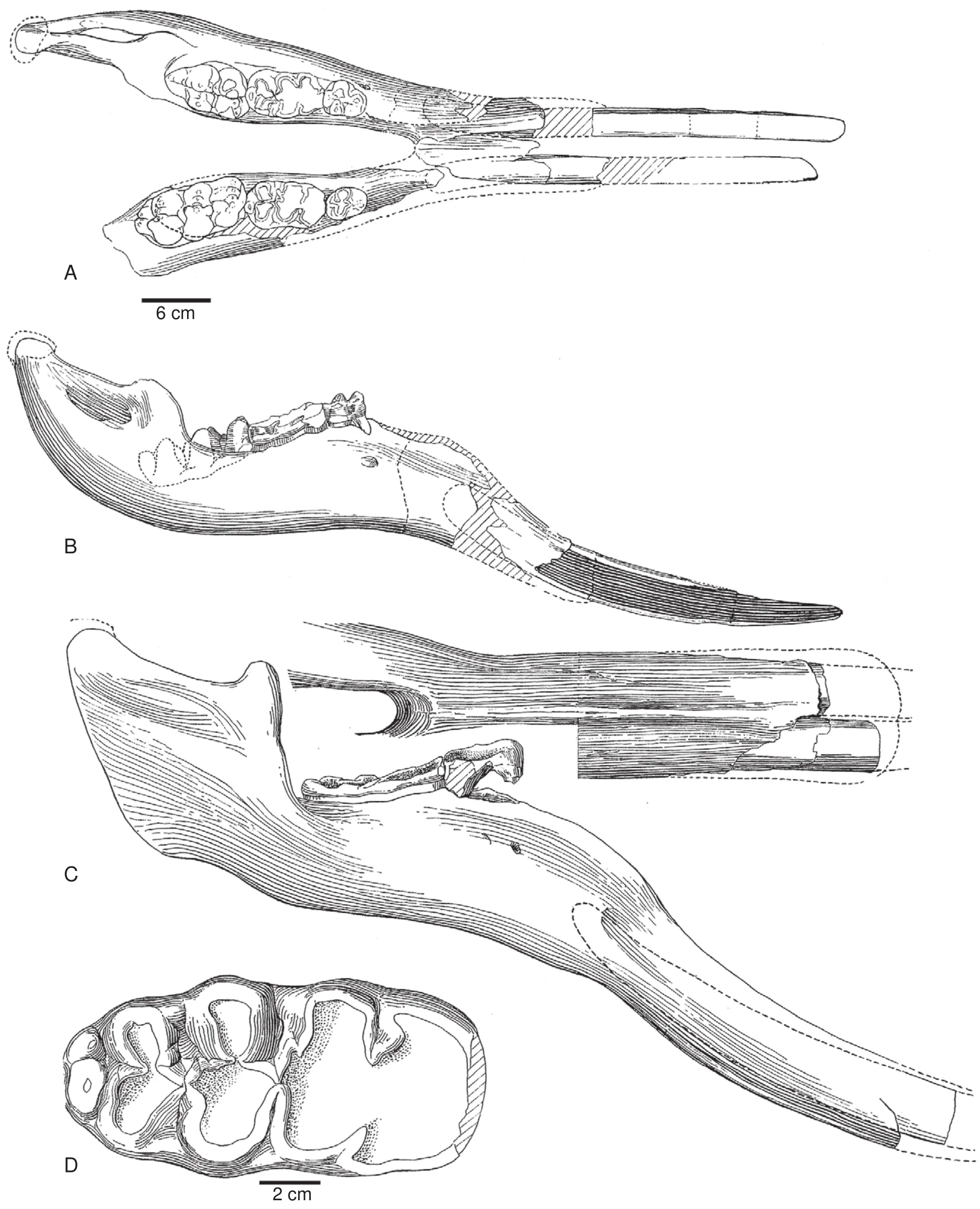

However, although Joleaud (1939)well captured a 19th century understanding of the South American gomphotheres, he apparently was unaware of work by Cabrera(1929)and Osborn (1923, 1926, 1936)that altered their taxonomy and perceived evolutionary relationships.Thus,Osborn identified two taxa of South American gomphotheres—one, a mountain gomphothere that he namedCor?dillerionand the other, a lowland gomphothere, he namedCuvieronius(Fig.2).Cabrera, however, took a different view of their taxonomy and chose to assign the gomphotheres from the environs of Buenos Aires, Argentina, to an otherwise North American genus,Stegomastodon, and to a new genus,Notiomastodon.He also made a nomenclatural mistake and applied the nameCuvieroniusto Osborn′s mountain gomphothere.Osborn (1936)took vigorous exception to Cabrera′s work (Cabrera, 1929), but unfortunately Osborn′s successors did not, and Cabrera′s taxonomy became widely used.

After Osborn and Cabrera, the most influential studies of South American gomphotheres were those of Hoffstetter (1950, 1952, 1955)and Simpson and Paula Couto(1957).Hoffstetter named the subgenusHaplomastodonofStegomastodon, and Simpson and Paula Couto elevatedHaplomastodonto generic rank.Although Hoffstetter had designatedMastodon chimboraziProa?o, 1922 as the type species ofHaplomastodon, Simpson and Paula Couto(mistakenly)consideredMastodon waringiHolland, 1920,to be the type species.Hoffstetter took vigorous exception to this, but subsequent workers perpetuated this error.Very important, though, was documentation of the morphology and variation of a large sample of “Haplomastodon war?ingi” from Minas Gerais in Brazil by Simpson and Paula Couto (1957).Similar documentation of variation in a sample ofCuvieronius hyodon(“Mastodon andium”)from Tarija, Bolivia, had earlier been published by Boule and Thevenin (1920).Also significant was recognition of four valid genera of South American gomphotheres by Simpson and Paul Couto (1957):Cuvieronius,Haplomastodon,NotiomastodonandStegomastodon.

Fig.2 Osborn (1923, 1926, 1936)first identified the dichotomy in South America between a mountain gomphothere he called Cor?dillerion and a lowland gomphothere he named Cuvieronius.Now, the mountain gomphothere is called Cuveronius and the lowland gomphothere is Notiomastodon (= Haplomastodon).(after Osborn, 1936).

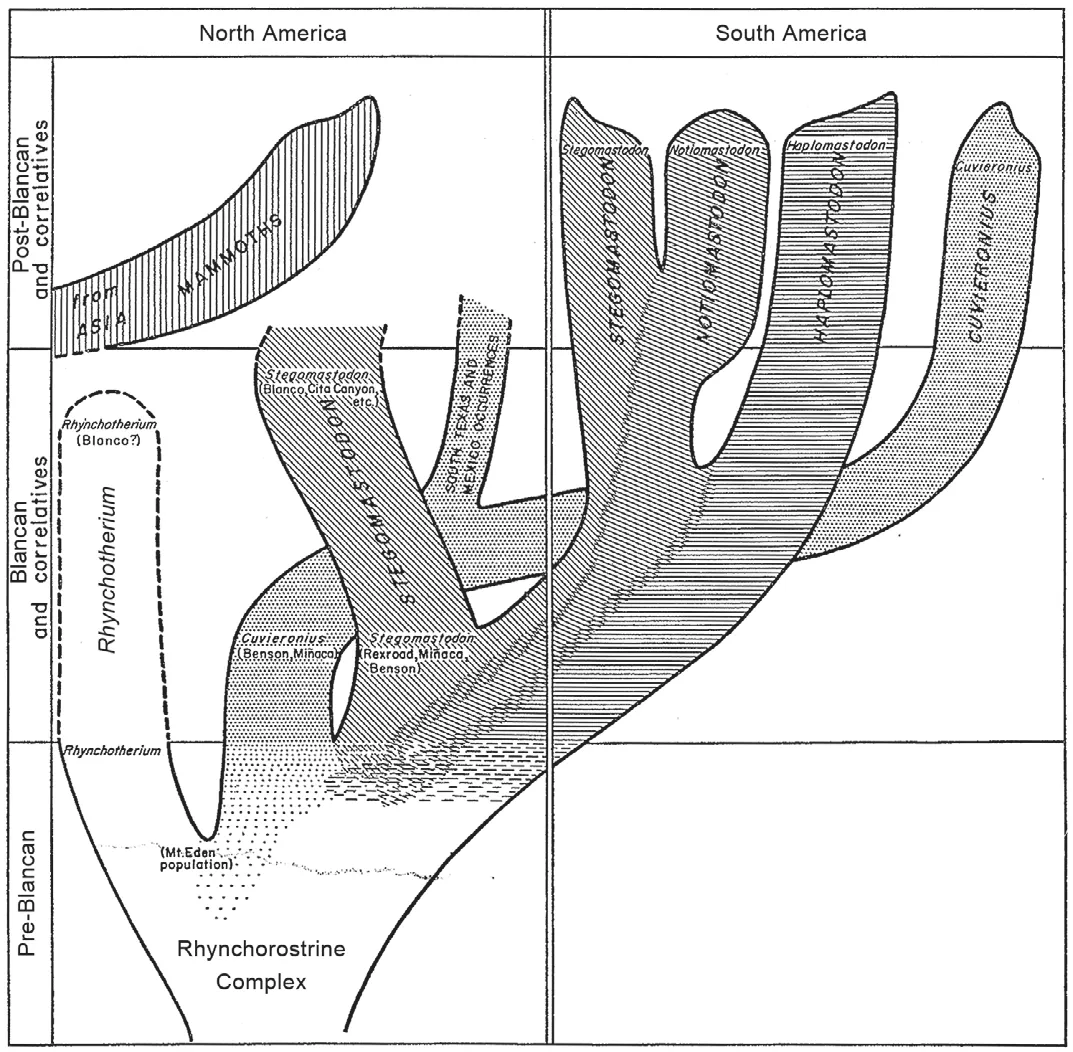

What followed were nearly 50 years of diverse commentary on the Neotropical gomphotheres, but no basic taxonomic works like those of Boule and Thevenin, Hoffstetter and Simpson and Paula Couto.There arose two different views of the palaeobiogeographic history of South American gomphotheres, well reflected by the summaries of Savage (1955)and Webb (1992).Savage (1955)stressed the morphological similarity of primitive North AmericanStegomastodonand the taxon Hoffstetter had namedHap?lomastodon.Savage (1955)thus envisioned two immigration events of proboscideans from North to South America during the Blancan—CuveroniusandStegomastodonas separate immigrants—the latter giving rise to South AmericanNotiomastodonandHaplomastodonwith parallel evolution of the separate North and South American stocks ofStegomastodon(Fig.3).

Webb (1992)took a different tack.He united all ofthe South American gomphotheres in the subfamily Notiomastodontinae and argued thatRhynchotheriumgave rise toCuvieroniusin North America during the Pliocene.Cuvieroniusthen immigrated in South America during the Early Pleistocene (Irvingtonian)and gave rise toNotio?mastodonandHaplomastodon.Until about a decade ago,this idea of a single Pliocene immigration of gomphotheres to South America was the prevalent view.

Fig.3 Savage’s (1955)phylogeny of Stegomastodon and related gomphotheres accepted Cabrera’s (1929)identification of Stego?mastodon in South America, making it necessary to have two separate lineages of Stegomastodon, north and south, evolve in parallel(after Savage, 1955).

During the last decade, several workers have re-examined the South American gomphotheres.More extensive has been the work of Alberdi, Prado and collaborators(e.g., Alberdi and Prado, 1995; Frassinetti and Alberdi,2000; Pradoet al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Alberdiet al., 2002,2004, 2007; Sánchezet al., 2003, 2004; Prado and Alberdi,2008).They published alpha taxonomic revisions of the Chilean, Brazilian and Argentinian material to recognize two genera:CuvieroniusandStegomastodon(=Notio?mastodonandHaplomastodon).They thereby reprised the dichotomy of a mountain gomphothere (Cuvieronius)and a lowland gomphothere (Stegomastodon)that arrived in South America by separate immigrations.Alberi and Prado see these immigrations as part of the GABI, occurring after the closure of the Panamanian isthmus.

Recently, the Alberdi-Prado synthesis has been criticized.In particular, applying the nameStegomastodonto any South American gomphothere fossil has been questioned, with various workers arguing that the nameSte?gomastodonshould not be applied to any South American gomphothere (Ferretti, 2008; Lucas and Alvarado, 2010;Lucaset al., 2011a, 2011b; Mothéet al., 2012a, 2012b).

Also, during essentially the last decade, a supposed new gomphothere taxon (Amahuacatherium)of putative Miocene age has been described from Peru.Fraileyet al.(1996)preliminarily published this fossil, Romero-Pttman(1996)named it and Campbellet al.(2000, 2001, 2006,2009, 2010)have argued that it is morphologically distinctive and that it comes from deposits that underlie an ~ 9 Ma unconformity.If correctly dated,Amahuacatheriumindicates the arrival of gomphotheres in South America during the Miocene, much earlier than other hypotheses of gomphothere dispersal.Thus, a MioceneAmahuacath?eriumintroduces a third hypothesis of gomphothere immigration in South America.

Thus have arisen three hypotheses of gomphothere dispersal to South America;

1)A single gomphothere immigration took place soon after closure of the Panamanian isthmus, ~ 2.5-3 Ma.

2)Two separate gomphothere immigrations took place after closure of the isthmus.

3)An earlier, Late Miocene (before 9 Ma)immigration brought gomphotheres into South America.

To evaluate these three hypotheses, three data sets need to be addressed: alpha taxonomy, dating (temporal [stratigraphic] distribution)and phylogeny.

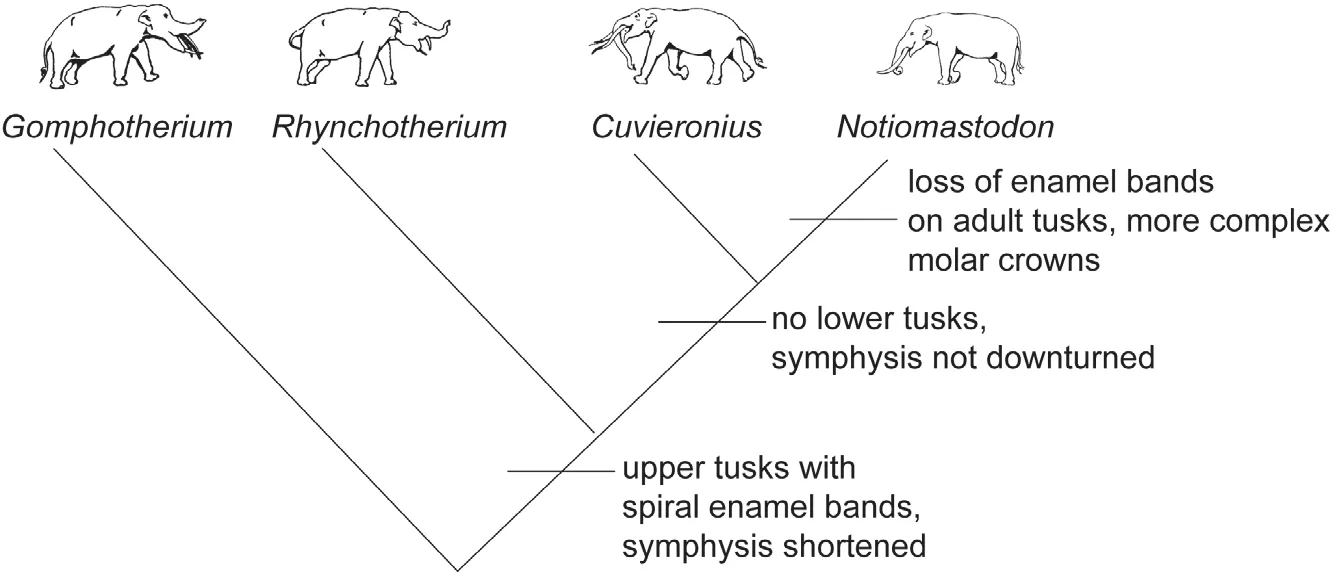

3 Taxonomy

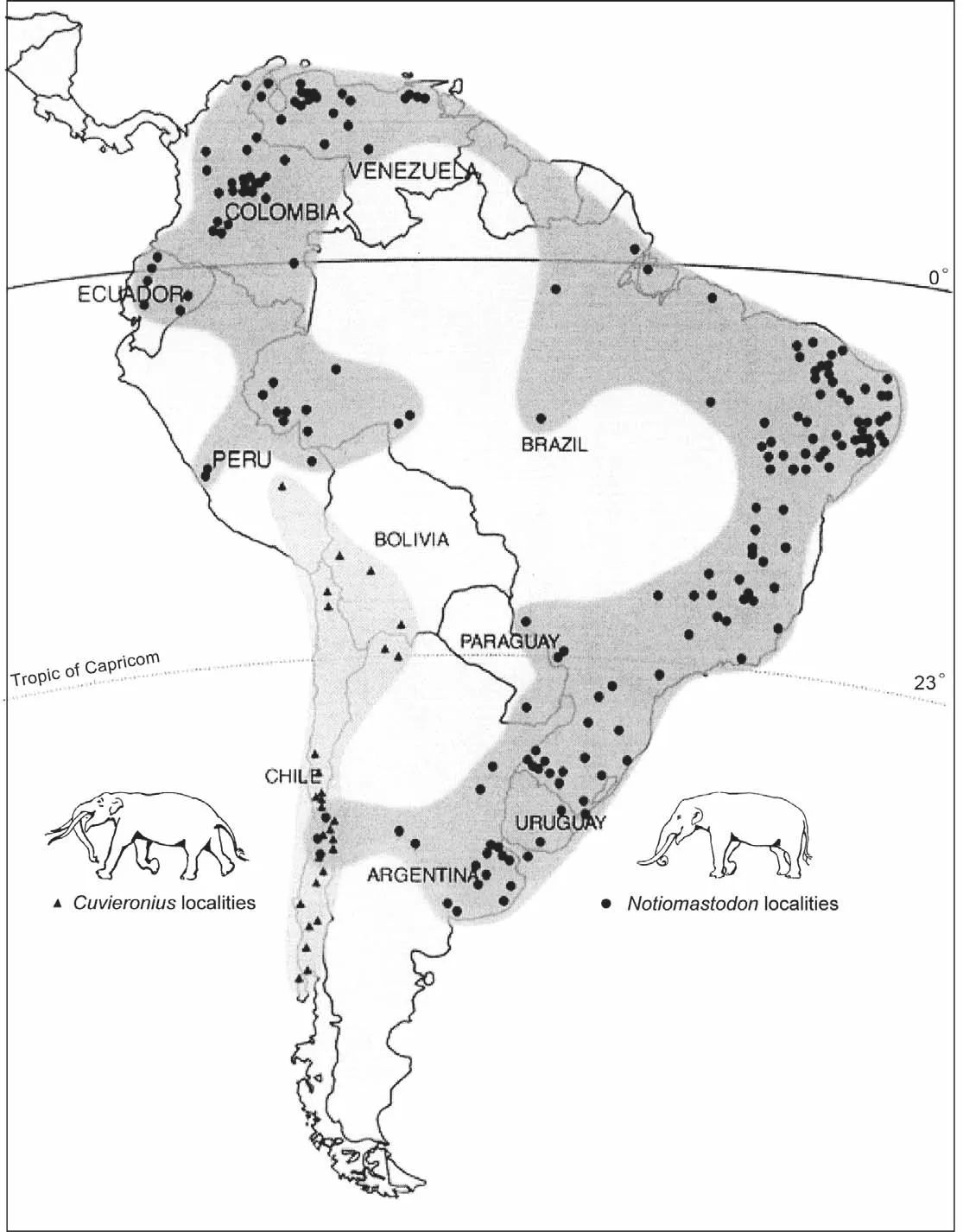

There has been much disagreement and confusion over the alpha taxonomy of Neotropical gomphotheres.I here recognize three valid genera of Neotropical gomphotheres:Gomphotherium,CuvieroniusandNotiomastodon.GomphotheriumandCuvieroniushave records in Central America, whereasCuvieroniusandNotiomastodonare known from South America (Fig.4).There are no records ofRhynchotheriumorStegomastodonin the tropics: both are North American genera known only as far south as Mexico (Lucas and Morgan, 2008; Lucaset al., 2011a,2011b; and discussion below).

3.1 Gomphotherium

Gomphotherium(Fig.5)is an Old World and New World gomphothere with a long stratigraphic range through most of the Miocene and Pliocene, characterized by its low and long skull with upper tusks with enamel bands, lower jaw with two elongate lower tusks in an elongate mandibular symphysis and last molars with 3-5 lophs/lophids that wear to single trefoils (e.g., Tobien,1973; Lambert and Shoshani, 1998).Gomphotheriumwas common in North America during the Miocene (Barstovian-Early Hemphillian), but rare during the Pliocene (Late Hemphillian).Its records in North America extend as far south as southern Mexico (e.g., Ferrusquia-Villafranca,1984, 1990; Lambert and Shoshani, 1998).A large number of species ofGomphotheriumhave been recognized,but Tobien (1978)argued that only one North American species is valid,G.productum.However, I believe the genus is more speciose in the New World (cf., Heckertet al.,2000)and that there are at least two species known from North America, and another is known from Central America.Thus, I accept the conclusion of Lucas and Morgan(2008)that the Central American speciesGomphotherium hondurensis(=Aybelodon hondurensis, =Blickotherium blicki)is not a species ofRhynchotherium, but instead a derived species ofGomphotherium(Fig.6).

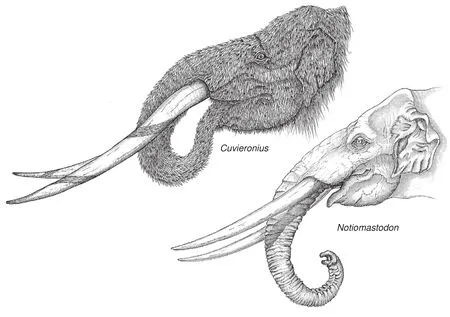

Lucas and Alvarado (2010)reviewed records ofGom?photheriumin Central America, which are in Guatemala,Honduras, El Salvador and possibly Costa Rica.These records are likely all of Hemphillian age, though the onlydefinitely dated records are from the Gracias Formation in Honduras.These are also the onlyGomphotheriumrecords in Central America that are not just isolated teeth.Frick(1933)first documented the Honduran Hemphillian gomphotheres, naming themAybelodon hondurensisandBlicko?therium blicki(Fig.6).It has long been agreed that these should be synonymized as one species, though this species was long assigned toRhynchotherium.Rhynchotheriumis otherwise a North American genus of Blancan age, so the presence of supposed Hemphillian rhynchotheres lead to the idea thatRhynchotheriumoriginated in Central America.

Fig.4 Principal occurrences of fossils of Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon (= Haplomastodon)in South America (after Mothé et al.,2012a).The light gray area encompasses the distribution of Cuvieronius fossils, whereas the dark gray area delineates the distribution of Notiomastodon fossils.

However, a vision of the taxonomy ofRhynchotheriumredefines the genus to exclude the Honduran taxon (Lucas and Morgan, 2008).Instead, the Honduran gompho-theres are a geologically young and advanced species ofGomphotherium,G.hondurensis.SimilarGomphotheriumare known from the Hemphillian of the USA, such asG.“riograndensis” from New Mexico (Frick, 1933).Gom?photheriumevidently came to Central America from North America during the Late Miocene and did not extend its distribution into South America.

Fig.5 Restoration of the head of Gomphotherium, by Pedro Toledo.Note the long and low skull and the upper and lower tusks.

3.2 Cuvieronius

Cuvieronius(Fig.7)is a New World gomphothere known from the Early Pleistocene of North America and the Pleistocene of Central and South America (e.g., Dudley, 1996; Lambert, 1996; Lambert and Shoshani, 1998;Pradoet al., 2005; Lucas, 2008a; Ferretti, 2008).In North America,Cuvieroniusrecords are known across Mexico(e.g., Montellano-Ballesteros, 2002; Alberdi and Corona-M., 2005)and in the southern United States in Arizona,New Mexico, Texas and Florida (e.g., Kurtén and Anderson, 1980; Dalquest and Schultz, 1992; Webb and Dudley,1995; Lucaset al., 1999, 2000; Hulbert, 2001; Bellet al.,2004; Lucas and Morgan, 2005; Lucas, 2008a).In South America,Cuvieroniusrecords extend from Peru through Chile (Fig.4).

Characteristic features ofCuvieroniusinclude its relatively long and low vaulted skull, large upper tusks with spiral enamel bands, lack of lower tusks, short mandibular symphysis that is not strongly downturned and bunolophodont third molars that have 4-5 lophs/lophids with slightly alternating cusps between them (Fig.8).The twisted upper tusk, with its spiral band of enamel, is a derived feature shared byCuvieroniusandRhynchotherium(see later discussion).

Most recent workers have generally regarded two species ofCuvieroniusas valid, the type speciesC.hyodon(Fischer, 1814)andC.tropicus(Cope, 1884)(cf., Shoshani and Tassy, 1996).Indeed, it became traditional to refer all North American (from Mexico northward)specimens ofCuvieroniustoC.tropicus, and to refer all South American specimens toC.hyodon.Some authors referred Central American (especially specimens from Honduras,Costa Rica and El Salvador)specimens toC.hyodon(e.g.,Laurito, 1988)whereas others referred them toC.tropicus(e.g., Webb and Perrigo, 1984).A few authors remained undecided as to any species-level assignments pending a revision, or simply fell back on using the type speciesC.hyodon(e.g., Lambert, 1996; Lambert and Shoshani,1998).However, as Lucas (2008a)concluded, extensive revision of the South American specimens ofCuvieronius(see especially Frassinetti and Alberdi, 2000; Pradoet al.,2002, 2003, 2005; Alberdiet al., 2004)has established arange of variation in molar morphology forC.hyodonthat encompasses the type specimen ofC.tropicus.

Fig.6 Selected Gomphotherium hondurensis from the Late Miocene (Hemphillian)of Honduras——holotypes of Blickotherium blicki and Aybelodon hondurensis from the Gracias local fauna.These specimens were long assigned to Rhynchotherium, but are now considered to be an advanced species of Gomphotherium (Lucas and Morgan, 2008).A-B-Holotype of Blickotherium blicki, lower jaw in occlusal (A)and right lateral (B)views; C-D-Holotype of Aybelodon hondurensis, lower jaw in ventral and lateral views (C)and right m3 in occlusal view (D)(modified from Frick, 1933; figs.4-5).One scale bar for A-C, separate scale bar for D.

Fig.7 Restoration of heads of Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon, by Pedro Toledo.Note the differences in the overall shape of the skulls and the tusks.

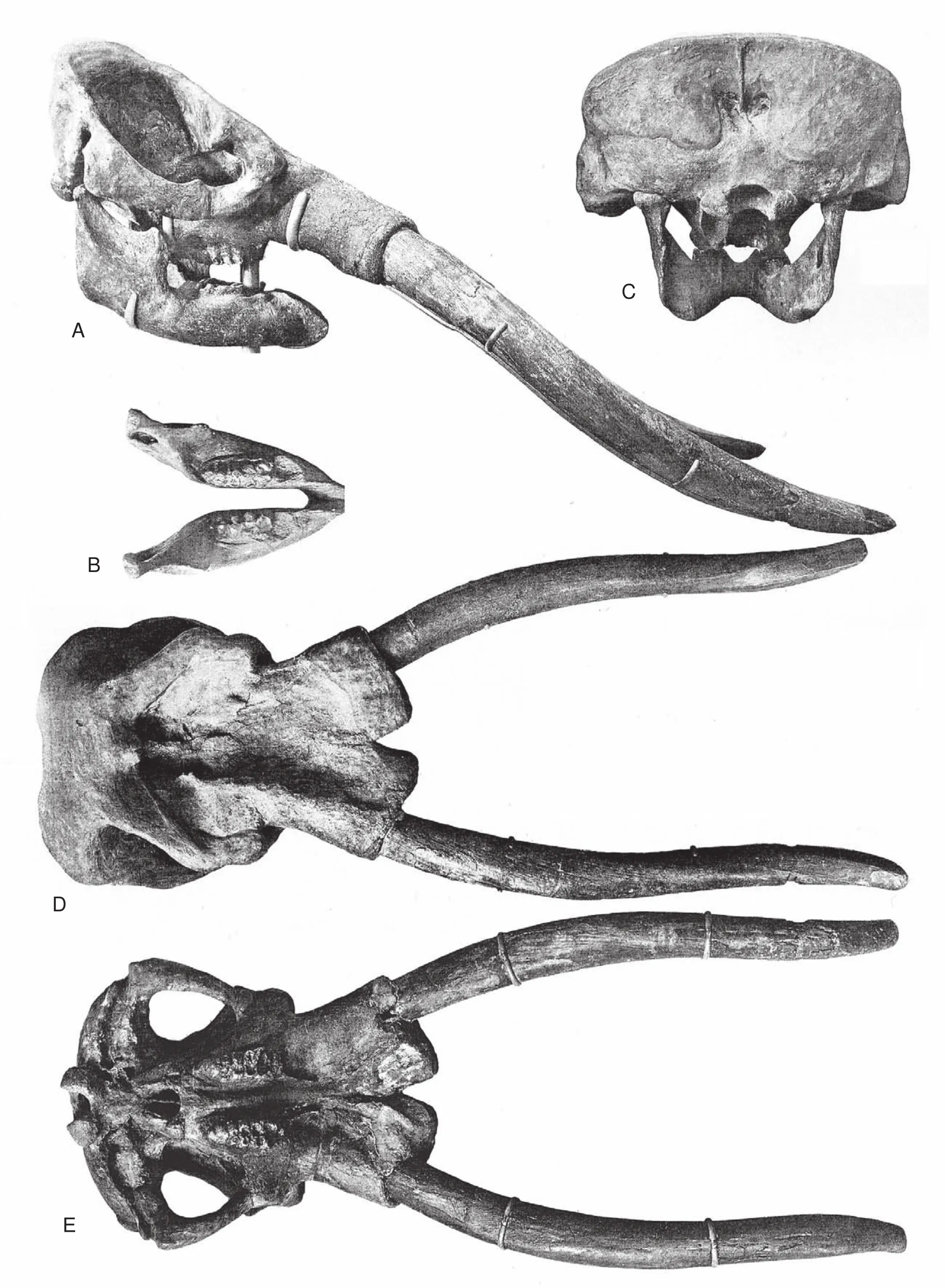

This suggests that only one polymorphic species ofCuvieroniusis present from the southern USA through South America (Lucas, 2008b).Recent action by the ICZN(Opinion 2279)has also stabilized the genus name by establishing a diagnostic neotype (from Tarija, Bolivia)for the type species,C.hyodon(Lucas, 2009b)(Fig.8).

3.3 Notiomastodon

Cabrera (1929)namedNotiomastodon ornatusfor a tusk and “associated” mandible (Fig.9)from the Upper Pleistocene at Playa del Barco on the Argentine Atlantic coast.He distinguished the genus from the other Argentine gomphothere fossils he assigned toStegomastodonby the presence of an enamel band on the juvenile tusks ofNo?tiomastodon.Osborn (1936)regardedNotiomastodonas a distinct genus, but Hoffstetter (1950, 1952)and Simpson and Paula Couto (1957)doubted the distinction Cabrera made betweenNotiomastodonand Argentine “Stegomas?todon”.Decades later, Madden (1980)first suggested that all of the Argentine gomphotheres described by Cabrera should be assigned toNotiomastodon.

Later rejection of assigning any South American gomphothere toStegomastodonhas led to recent wide use ofNotiomastodonas a valid genus (Ferretti, 2008; Lucas and Alvarado, 2010; Lucaset al., 2011a; Mothéet al., 2012a).Notiomastodonis characterized by its relatively short and tall (elephantoid)skull, lack of lower tusks, straight to slightly curved tusks that lack enamel bands in the adult and, in some specimens, relatively complex molar crowns(Figs.7, 9).

Haplomastodonhas been a particularly problematic name for South American gomphothere taxonomy.Hoffstetter (1952)namedHaplomastodonas a subgenus ofStegomastodon, but it was soon raised to separate generic status by Simpson and Paula Couto (1957).Indeed, Simpson and Paula Couto′s (1957)monographic study establishedHaplomastodonas one of the best known South American gomphotheres.The genus was then widely rec-

ognized across Brazil and Argentina.However, Alberdi and Prado (1995)challenged the idea thatHaplomastodonis a distinct genus, instead arguing that it is a synonym ofStegomastodon.This synonymy has been accepted in the sense thatHaplomastodonis now seen as a synonym ofNotiomastodon, which also includes all South American specimens Alberdi/Prado assigned toStegomastodon(see Mothéet al., 2012a for the most detailed discussion of this taxonomy).

Fig.8 Neotype skull and lower jaw of Cuvieronius hyodon, from Tarija, Bolivia.A-Right lateral view of skull and lower jaw; BOcclusal view of lower jaw; C-Occipital view of skull and lower jaw; D-Dorsal view of skull; E-Ventral view of skull.For scale,maximum length of skull (including tusks)= 210 cm (modified from Boule and Thevenin, 1920; pls.1-3).

Fig.9 Selected specimens of Notiomastodon from Argentina.A-D-Syntypes of N.ornatus, subadult lower jaw in occlusal and lateral views (A-B)and “associated” upper tusk in lateral and superior views (C-D); The tusk is the lectotype of N.ornatus (Simpson and Paula Couto, 1957).Note the enamel band on the tusk.E-Characteristic left m3 with relatively complex crown structure; F-Skull with tusks, occiput and braincase partly restored, on display at the Museo de la Plata; A-E are in the collection of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales and are catalogued as MACN 2157 (A-D)and 5213 (E); A-D are from Playa del Barco, whereas E is from the Río Paraná; both localities are Late Pleistocene; F is in the collection of the Museo de la Plata catalogued as MLP 8-1; for scale, total length of the left tusk is 150 cm.The specimen is from the Upper Pleistocene of Arecifes, Argentina.

Also note, that the type species ofHaplomastodon,Masthodon chimboraziProa?o, 1922, is anomen dubium(diagnostic portions of its holotype were long ago destroyed in a fire)(Lucas, 2008b).The speciesHaplomas?todon waringi, regarded by many (erroneously)as the type species of the genus, is based on an undiagnostic holotype,so it, too, is anomen dubium(Lucas, 2008b).Attempts to designate diagnostic neotypes for these species (Ficarelliet al., 1993, 1995; Lucas, 2009a)have recently been rejected by the ICZN (Opinion 2308), soHaplomastodonis technically anomen dubium.This problematic name is thus best abandoned in favor ofNotiomastodon.

3.4 Amahuacatherium

Amahuacatheriumis based on two dentary fragments with incomplete left m2 and complete m3s (Fig.10B)found along a river bank in eastern Peru (Romero-Pittman, 1996).More of the fossil (the lower jaw, some postcrania,etc.)was originally discovered, but these remains were destroyed bya flood while the fossil was being collected (Campbellet al.,2000).Fraileyet al.(1996, p.295)first published the fossil, stating that it came from the upper Miocene (Huayquerian LMA)Solim?es Formation.It is distinguished by its relatively complex molar crowns, which have accessory conules, and by its thick and medially inflated horizontal ramus of the dentary.Romero-Pittman (1996)named the taxonAmahuacatherium peruviumwithout providing an explicit diagnosis, but she did claim that the extra cusps in the lingual valleys of the molars are distinctive.

Fig.10 Holotype m3 of Amahuacatherium peruvium (B)compared to two very similar m3’s of Notiomastodon from Argentina (A, C).A is in the collection of the Museo de la Plata catalogued as MLP 68-X-6-9 and has no precise locality data other than Pleistocene,Argentina; B is after Campbell et al. (2000); C is also in the Museo de la Plata collection and is catalogued as MLP 8-407 and is from the Pleistocene at Mercedes in Buenos Aires Province.The teeth are shown to the same scale, though A and C have crown lengths of 220 mm, whereas B has a crown length of 187 mm.

Since its redescription by Campbellet al.(2000), there has been disagreement over the morphology of the fossil(tusks/no tusks, shape/depth of mandibular horizontal ramus, whether m3 is within the range of variation of “Hap?lomastodon” or not)and its geological age (Late Miocene or younger)(Alberdiet al., 2002, 2004; Gutiérrezet al.,2005; Pradoet al., 2005; Woodburneet al., 2006; Ferretti,2008; Lucas and Alvarado, 2010; Woodburne, 2010).My conclusion is that molar metrics and morphology of the holotype ofAmahuacatherium(e.g., Fig.10)are well within the range of other specimens assigned to “Stegomasto?don” (=Notiomastodon)by Alberdiet al.(2004), that there is no compelling evidence for the presence of tusks in the mandible ofAmahuacatheriumand that the supposed diagnostic features of the mandible are questionable.I thus agree with Alberdiet al.(2002, 2004)and Ferretti (2008)that morphology does not distinguishAmahuacatheriuumfromNotiomastodon(=Haplomastodon, = “Stegomasto?don”).As Shoshani and Tassy (2005, p.7)well observed,“AmahuacatheriumandHaplomastodon[hereNotiomas?todon] are undistinguishable on morphological grounds.”

There is a Late Miocene (~ 8-9 Ma)pulse of mammal immigration between North and South America, when two sloths migrated from south to north and a large procyonid migrated from north to south (e.g., Lucas and Alvarado, 1994; Morgan, 2005), soAmahuacatheriumcould conceivably be part of this event.However, the Miocene age ofAmahuacatheriumis poorly supported and rejected here, as discussed below.

4 Age relationships

Records of gomphothere proboscidean fossils from Central and South America have diverse and often imprecise age constraints.In North America, the temporal ranges ofGomphotheriumandCuvieroniusare well established by a combination of biostratigraphy, magnetostratigraphy and radioisotopic dating (Bellet al., 2004; Tedfordet al.,2004; Lucas, 2008b; Lucas and Morgan, 2008)(Fig.11).Lucas and Alvarado (2010)provided a detailed review of the Central American record of proboscideans and established the temporal ranges ofGomphotheriumandCuvi?eronius(Fig.11).

The South American record of gomphothere fossils extends from Venezuela to Chile (Fig.4), and most occurrences are of Late Pleistocene (Lujanian)age.However,some records are evidently older, Bonaerian or Ensanadan.In Argentina, there is a gomphothere record (based on postcrania)of Marplatan age, ~ 2.5 Ma (Lópezet al.,2001; Regueroet al., 2007).This is the oldest, well-dated record of a South American gomphothere.

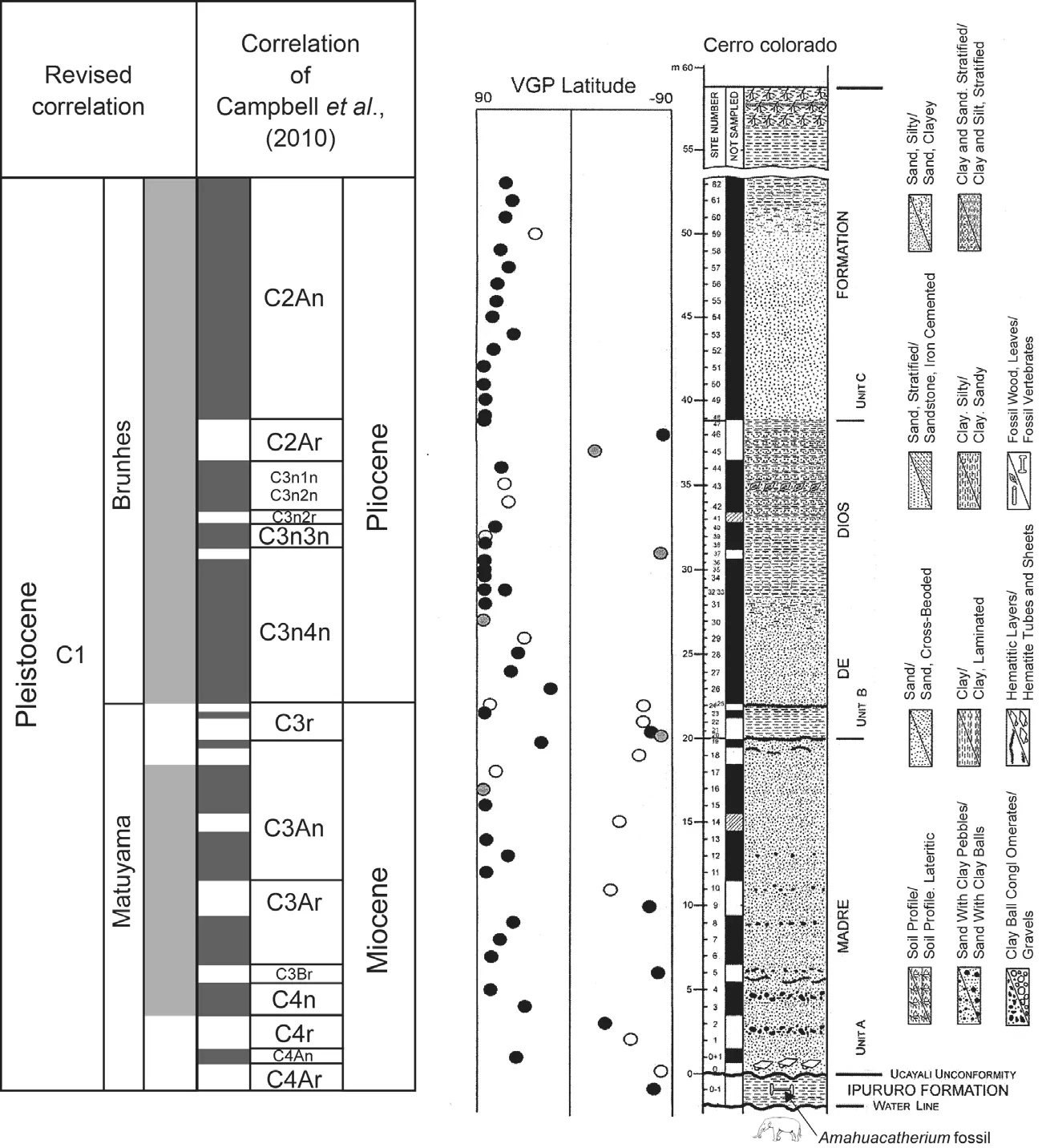

TheAmahuacatheriumtype is from the Ipururo Formation below what has been termed the Ucayali unconformity, estimated to be no younger than ~ 9 Ma (Campbellet al., 2000, 2001, 2006, 2009, 2010).At a locality ~ 250 km from theAmahuacatheriumsite, the Ucayali unconformity is ~ 4 m below an ash bed with an Ar/Ar date of ~ 9 Ma(Campbellet al., 2001).

Campbellet al.(2001)argue that this unconformity is pervasive throughout lowland Amazonia and is ~ 9 to 15 Ma throughout its extent.However, the presence of a regional unconformity in the Amazon basin of ~ 9-15 Ma is not accepted by other workers and can be rejected based on both lithostratigraphic and biostratigraphic data.Instead of a single, pervasive Miocene unconformity, Latrubesseet al.(2007, 2010)well represent diverse work (also see especially Simpson and Paula Couto, 1981)that identifies a complex set of terraces, channel fills and reworked deposits above a compound unconformity that ranges in age from Miocene to Pleistocene, separating the Solim?es/Ipururo Formation from overlying deposits of the Madre de Dios Formation and correlative units.Indeed, the Solim?es Formation in Brazil, the same lithosome as the Ipururo Formation in Peru, has a mammal fauna of Huayquerian age,which is an age of ~ 6-9 Ma (Flynn and Swisher, 1995;Woodburneet al., 2006)(Fig.11).Furthermore, the 9 Ma ash bed is in the Madre de Dios Formation, stratigraphically “above” basal gravels that contain mammals that have long been assigned a Pleistocene age (e.g., Simpson and Paula Couto, 1981).This induced Campbellet al.(2000,2009)to disavow a Pleistocene age for at least some of these mammals, including those reported by Simpson and Paula Couto (1981)and Latrubesse and Rancay (1998),among others.

I prefer to use biostratigraphy to assign an age to the fossil mammals found in the Solim?es/Ipururo and overlying Madre de Dios Formations and not simply project an Ar/Ar age of 9 Ma from a single outcrop through such a complexlithosome.Amahuacatheriumis morphologically indistinguishable from PleistoceneNotiomastodon.It and other Pleistocene taxa from the Madre de Dios Formation (and this includes the peccaries recently claimed to be Miocene by Frailey and Campbell, 2012; these are morphologically the same as Pleistocene taxa:e.g., Simpson and Paula Couto, 1981)are much younger than the Huayquerian mammals of the underlying Solim?es/Ipururo Formation.

Fig.11 Correlation of North American and South American land-mammal “ages” (after Woodburne et al., 2006 and Hilgen et al., 2012)showing temporal distribution of selected events relevant to the evolution and palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres.

The only other dataset from theAmahuacatheriumsite used to argue for a Miocene age is the magnetostratigraphy published by Campbellet al.(2010).However, these magnetostratigraphic data (Fig.12)and their interpretation and correlation by Campbellet al.(2010)are questionable:

1)Above their magnetic site 25 there is no convincing evidence of reversed polarity.Sites 45-46 are one questionable site and one reliably reversed site; site 41 shows no data to support reversed polarity; and site 37 is one questionable site.Therefore, the section above meter 23 is more reliably interpreted as being entirely of normal polarity (note also how many sites are normal in this stratigraphic interval).

2)A case can be made for reversed polarity in the interval of magnetic sites 18-24, though the data are very much of mixed polarity and not a very strong indicator.

Fig.12 Magnetostratigraphy of the Amahuacatherium type locality (after Campbell et al., 2010)showing reinterpretation of the magnetic polarity record at the locality and alternative correlations of the magnetostratigraphy.Note that if the reversed interval at about the 20 m level is abandoned, then the entire section is normal down to the 3 m level and this could all be correlated to Brunhes.

3)The case for reversed polarity intervals indicated below the level of site 17 is also very weak.No reversed polarity in this interval is supported by more than one site,and most of the sites are normal.The strongest case for reversed polarity is around the Ucayali unconformity.

4)The entire stratigraphic section is only 65 meters thick, yet by the correlation advocated by Campbelletal.(2010)it is a complete record of Chrons 4Ar through Chron 2An, about 6 million years (Fig.12).Given that the section is of fluvial origin, 6 million years = 65 meters of fluvial sediment implies many hiatuses in the section or an abnormally low rate of sedimentation.Also, a major unconformity (Ucayali unconformity)is inferred near the base of the section, so some of the magnetic polarity his-tory may be missing at this hiatus.

My conclusion is that this section is almost totally of normal polarity (Fig.12).This further undermines correlating it to Chrons 4Ar through 2An, as that interval consists of 17 reversed and normal polarity intervals, far more than are reliably present.Given that a Pleistocene gomphothere (“Amahuacatherium”)is present near the base of the section, a more supportable correlation is to the younger part of Chron 1 (Fig.12).The correlation shown in Figure 12 accepts a reversed interval for sites 18-24,but this is weakly supported.If that reversal is rejected,then the section is of normal polarity down to the level of site 3 and should correlate almost entirely to Brunhes.

An important point is that the magnetostratigraphy by itself does not independently correlate the section.This correlation relies on a datum, which for Campbellet al.is their projection of the 9 Ma radioisotopic age into the section.However, the mammal fossil at the section does not, by itself, indicate a Miocene age.If considered Pleistocene (see above), this fossil mandates a much different correlation of the magnetostratigraphy than that advocated by Campbellet al.(2010).Thus, based on the reanalysis presented here, the magnetostratigraphy of theAmahua?catheriumsite does not demonstrate a Miocene age.

5 Phylogenetic relationships

All workers agree that the South American gomphotheres were ultimately descended from North American gomphotheres.This has never been questioned, and the phylogenetic problems regarding the South American gomphotheres have long centered on the putative presence ofStegomastodonin South America, which requires two separate evolutionary lineages—one that producedCu?vieronius, the otherStegomastodon—to have immigrated to South America (e.g., Savage, 1955; Prado and Alberdi,2008).Rejection of the presence ofStegomastodonin South America considerably simplifies the phylogenetic issues.

5.1 Ancestry of Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon

Various workers have argued for a close relationship ofCuvieroniusandRhynchotherium—both share a highly derived upper tusk morphology in which enamel bands are spiraled around the tusk′s long axis (Fig.13).Derivation ofRhynchotheriumfrom North AmericanGomphotheriumis also widely accepted.Thus, an evolutionary lineage in North America of three, temporally-overlapping gomphothere genera can be well supported by morphological, geographic and stratigraphic data: advancedGomphotheriumgave rise toRhynchotheriumduring the Late Hemphillian,andRhynchotheriumgave rise toCuvieroniusby the end of the Blancan (e.g., Webb, 1992; Lambert and Shoshani,1998; Lucas and Morgan, 2008)(Fig.11).

EliminatingAmahuacatheriumas an invalid taxon based on a specimen ofNotiomastodon, and rejecting the presence ofStegomastodonin South America, indicate that only one evolutionary lineage of gomphotheres, that ofCuvieronius, immigrated in South America (Fig.11).Derivation ofNotiomastodonfromCuvieroniusrequires the evolution of a tall, elephantoid skull from the low skull ofCuvieronius, the modification of the tusks from enamel spiral to straight/slightly curved and lacking an enamelband in the adult and some development of more complex molar crowns.What has long confused the issue is that very similar features evolved in North AmericanStego?mastodon, probably from aGomphotheriumancestry.This evolutionary convergence betweenNotiomastodonandStegomastodonhas been denied by those who regard the two taxa as one and the same.But, convergence is never perfect, and there are ample morphological features that distinguishStegomastodonfromNotiomastodon; they are not the same taxon (Lucaset al., 2011a; Mothéet al.,2012a).Thus, like Mothéet al.(2012a), I advocate derivation ofNotiomastodonfromCuvieronius.

Fig.13 Phylogenetic hypothesis of the relationships of the Neotropical gomphotheres (modified from Lucas and Morgan, 2008).

5.2 Sinomastodon

Tobienet al.(1986)coined the nameSinomastodonforMastodon intermedius(Teilhard and Trassaert, 1937),from the Late Miocene (Baodean, which is ~ Turolian)of the Yushe Basin in Shanxi Province, the People′s Republic of China.Known from dental and mandibular material,the genus is distinguished primarily by its lack of lower tusks, short and spout-like mandibular symphysis and four-lophed m3.The latest taxonomic review of the genus recognizes three species from the Plio-Pleistocene of China (Chen, 1999).

Tobienet al.(1986)suggested a close relationship betweenSinomastodonand the New World gomphotheres they included in the “Notiomastodontinae”, namelyCuvieronius,Haplomastodon,NotiomastodonandStego?mastodon.More precisely, they suggested derivation ofSinomastodonfrom their Notiomastodontinae and thus an immigration from North America to Asia.Cladistic analysis by Tassy (1996)and Prado and Alberdi (2008)supported this idea.

Thus, Prado and Alberdi (2008; also see Alberdiet al.,2007)unitedSinomastodonwith a cladeCuvieronius+“Stegomastodon” (Notiomastodonas used here)based on two character states—lower tusk absent and short, spoutlike mandibular symphysis.Two character states unite theCuvieronius+ “Stegomastodon” clade in their analysis—P2-4/p2-4 absent and M3 with five lophs.Nevertheless,this analysis ignores the very different molar structure ofSinomastodon, which is much more derived than that of the South American gomphotheres (Fig.14).The spoutlike symphysis is also highly variable among South American gomphotheres (cf., Boule and Thevenin, 1920)and has evolved independently in mammoths, so it may not be a reliable character.Furthermore, the short mandible/short symphysis is 100% correlated with a lack of lower tusks,so these are redundant characters (Cozzuolet al., 2012).

Cozzuolet al.(2012)reevaluated the cladistic analysis of Prado and Alberdi (2008)by different scoring of some of their characters.The new analysis recovered a polytomy ofGnathobeledon,Sinomastodon,Eubelodon,Rhynchoth?eriumand the cladeCuvieronius+ “Stegomastodon”.They concluded that “Sinomastodonis not supported as a sister group of the South American gomphotheres, and the biogeographic derivations presented in Alberdiet al.(2007)[vicariance of a common ancestor of AsianSinomastodonand New WorldCuvieronius+ “Stegomastodon”] are invalidated” (Cozzuolet al., 2012, p.40).

Chen (1999)also questioned a close relationship betweenSinomastodonand any New World gomphothere for three reasons: (1)no fossils ofSinomastodonhave been found in the supposed transitional region, between eastern China and western North America; (2)the molars ofSinomastodonhave a much simpler structure than in the notiomastodontines; and (3)Sinomastodonis both older than and temporally overlaps the notiomastodontines.It strikes me that the criticisms of Chen (1999)and Cozzuolet al.(2012)are compelling.Particularly significant is the different molar structure ofSinomastodon, and it seems highly likely the similarities in jaw structure are convergent, based on independent loss of the lower tusks.A close relationship betweenSinomastodonand the South American gomphotheres thus can be rejected.

5.3 Amahuacatherium

Mothéet al.(2012b)have presented the most recent phylogenetic analysis of the South American gomphotheres.In their analysis, they regardAmahuacatheriumas a valid taxon of Miocene age.They present three phylogenetic hypotheses of the possible relationships ofCuvi?eronius,Notiomastodon(=Haplomastodon)andAmah?uacatherium.All three hypotheses imply the presence of an ancestor ofNotiomastodonand/orCuvieroniusthat predatesAmahuacatherium, which would be a common ancestor older than 9 Ma.No such ancestor is known, andCuvieroniushas a fossil record no older than Late Blancan~ 3 Ma.Thus, acceptingAmahuacatheriumas valid and Miocene and incorporating it into phylogenetic hypotheses requires positing hypothetical ancestors and ghost lineages that are very long and for which two centuries of collecting have produced no evidence.This further weakens the case for a Miocene gomphothere in South America.

6 Conclusions

The above review supports the following conclusions:

Fig.14 Holotype and referred specimen of Sinomastodon intermedius from the Miocene of the Yushe Basin, Shanxi Province, the People’s Republic of China (from Teilhard and Traessart, 1937).A-B-Holotype lower jaw in occlusal (A)and oblique lateral (B)views; C-Occlusal view of referred left m3.For scale, the left m3 in A-B is ~ 182 mm long, whereas the m3 in C is ~ 190 mm long.

1)There are only two genera of South American gomphotheres:CuvieroniusandNotiomastodon(=Haplomas?todon).Stegomastodonis a strictly North American genus.Amahuacatheriumis invalid, being based on a specimen ofNotiomastodon.

2)The oldest, well-dated South American gomphothere is ~ 2.5 Ma from Argentina.A Miocene (older than 9 Ma)age of theAmahuacatheriumtype material is refuted by mammalian biostratigraphy and a reanalysis of relevant magnetostratigraphy.

3)The North American evolutionary lineageGompho?theriumgave rise toRhynchotheriumduring the Hemphillian, andRhynchotheriumgave rise toCuvieroniusby Blancan time.Cuvieroniusgave rise toNotiomastodonin South America.

Thus, the biogeographic and evolutionary history of South American gomphotheres is best explained as beginning with a single immigration ofCuvieroniusfrom Central America to South America just after the closure of the Panamanian isthmus, about 2.5-3.0 Ma.Cuvieroniusgave rise toNotiomastodonin South America during the Pleistocene, so the single immigration of gomphotheresinto South America was followed by a modest evolutionary diversification.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Marco Ferretti, Gary Morgan, Mike Pasenko and Mike Woodburne for helpful discussions and information.Collaboration with Guillermo Alvarado on the Central American record of proboscideans much influenced this work.Collection managers and curators at diverse institutions in Europe, North America, Central America and South America made access to critical fossils possible.Gary Morgan, Mike Pasenko and two anonymous reviewers made helpful comments that improved the manuscript.In 2010, Sylvia Aramayo (1944-2012)took me to Playa del Barco on the Argentine coast, the type locality ofNotiomastodon, and I dedicate this paper to the memory of this good friend, fine geologist and talented ichnologist.

Alberdi, M.T., Corona-M., E., 2005.Revisión de los gonfoterios en el Cenozoico tardío de México.Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geologicas, 22: 246-260.

Alberdi, M.T., Prado, J.L., 1995.Los mastodontes de América del Sur.In: Alberdi, M.T., Leone, G., Tonni, E., (eds).Evolución biológica y climática de la región Pampeana durante los últimos cinco millones de a?os.Madrid: Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, 279-292.

Alberdi, M.T., Prado, J.L., Cartelle, C., 2002.El registro deStego?mastodon(Mammalia, Gomphotheriidae)en el Pleistoceno superior de Brasil.Revista Espa?ola de Paleontología, 17: 217-235.

Alberdi, M.T., Prado, J.L., Salas, R., 2004.The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea)from Peru.Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Pal?ontologie Abhandlungen, 231: 423-452.

Alberdi, M.T., Prado, J.L., Ortiz-Jaureguizar, E., Posadas, P., Donato, M., 2007.Historical biogeography of trilophodont gomphotheres (Mammalia, Proboscidea)reconstructed applying dispersion-vicariance analysis.Cuaderno Museo Geomineralogía Instituto Geología Minas Espa?a, 8: 9-14.

Bell, C.J., Lundelius, E.L.Jr., Barnosky, A.D., Graham, R.W.,Lindsay, E.H., Ruez, D.R.Jr., Semken, H.A.Jr., Webb, S.D.,Zakrzewski, R.J., 2004.The Blancan, Irvingtonian, and Rancholabrean mammal ages.In: Woodburne, M.O., (ed).Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America.New York:Columbia University Press, 232-314.

Boule, M., Thevenin, A., 1920.Mammifères fossiles de Tarija.París:Soudier, 1-256.

Cabrera, A., 1929.Una revisión de los mastodontes Argentinos.Revista Museo de La Plata, 32: 61-144.

Campbell, K.E.Jr., Frailey, C.D., Romero-Pittman, L., 2000.The late Miocene gomphothereAmahuacatherium peruvium(Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae)from Amazonian Peru: Implications for the great American faunal interchange.República de Peru Sector Energía y Minas Instituto Geológico Minero Metalúrgico Boletín, 23: 1-152.

Campbell, K.E.Jr., Frailey, C.D., Romero-Pittman, L., 2006.The Pan-Amazonian Ucayali peneplain, late Neogene sedimentation in Amazonia, and the birth of the modern Amazon River system.Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 239: 166-219.

Campbell, K.E.Jr., Heizler, M., Frailey, C.D., Romero-Pittman, L.,Prothero, D.R., 2001.Upper Cenozoic chronostratigraphy of the southwestern Amazon basin.Geology, 29: 595-598.

Campbell, K.E.Jr., Frailey, C.D., Romero-Pittman, L., 2009.In defense ofAmahuacatherium(Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae).Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Pal?ontologie Abhandlungen,252: 113-128.

Campbell, K.E.Jr., Prothero, D.R., Romero-Pittman, L., Hertel,F., Rivera, N., 2010.Amazonian magnetostratigraphy: Dating the first pulse of the Great American Faunal Interchange.Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 29: 619-626.

Chen, G., 1999.Sinomastodon(Proboscidea, Mammalia)from the Pliocene and early-middle Pleistocene of China.Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 179-187.

Cope, E.D., 1884.The extinct Mammalia of the Valley of Mexico.Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 22: 1-21.

Cozzuol, M.A., Mothé, D., Avilla, L.S., 2012.A critical appraisal of the phylogenetic proposals from the South American Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea: Mammalia).Quaternary International, 255:36-41.

Cuvier, G., 1806.Sur différentes dents du genre des mastodontes,mais d′espèces moindres que celle de l′Ohio, trouvées en plusiers lieux des deux continents.Annales du Museum d′Histoire Naturelle, 8: 401-424.

Dalquest, W.W., Schultz, G.E., 1992.Ice age mammals of northwestern Texas.Wichita Falls: Midwestern State University Press,1-309.

Dudley, J.P., 1996.Mammoths, gomphotheres, and the great American faunal interchange.In: Shoshani, J., Tassy, P., (eds).The Proboscidea.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 289-295.

Ferretti, M.P., 2008.A review of South American proboscideans.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin,44: 381-391.

Ferrusquia-Villafranca, I., 1984.A review of early and middle Miocene Tertiary faunas of North America.Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4: 187-198.

Ferrusquia-Villafranca, I., 1990.Biostratigraphy of the Mexican continental Miocene.Part I, Introduction and the northwestern and central faunas; Part II, the southeastern (Oaxacan)faunas and concluding remarks on the discussed vertebrate record.Universidad Nacional Autónoma México Instituto de Geologia Paleonto-logia Mexicana, 56: 7-109.

Ficcarelli, G., Borselli, V., Moreno Espinosa, M., Torre, D., 1993.NewHaplomastodonfinds from the late Pleistocene of northern Ecuador.Geobios, 26: 231-240.

Ficcarelli, G., Borselli, V., Herrera, G., Moreno Espinosa, M., Torre,D., 1995.Taxonomic remarks on the South American mastodons referred toHaplomastodonandCuvieronius.Geobios, 28: 745-756.

Fischer De Waldheim, G., 1814.Zoognosia.Tabulis synopticis illustrat, 3: 1-694.

Flynn, J.J., Swisher, C.C., 1995.Cenozoic South American Landmammal ages: correlation to global geochronologies.In: Berggren, W.A., Kent, D.V., Handerbol, J., (eds).Geochronology,time scales and correlation: Framework for a historical geology.SEPM Special Publication, 54: 317-333.

Frailey, C.D., Campbell, K.E.Jr., 2012.Two new genera of peccaries (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Tayassuidae)from upper Miocene deposits of the Amazon Basin.Journal of Paleontology, 86:852-877.

Frailey, C.D., Campbell, K.E.Jr., Romero-Pittman, L., 1996.A new proboscidean from Amazonian Peru.In: Shoshani, J., Tassy,P., (eds).The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives.Oxford: Oxford University Press,295.

Frassinetti, D., Alberdi, T., 2000.Revisión y estudio de los restos fósiles de mastodontes de Chile (Gomphotheriidae):Cuvieronius hyodon, Pleistoceno superior.Estudios Geologicos, 56: 197-208.

Frick, C., 1933.New remains of trilophodont-tetrabelodont mastodons.Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 59:505-652.

Gutiérrez, M., Alberdi, M.T., Prado, J., Perea, D., 2005.Late PleistoceneStegomastodon(Mammalia, Proboscidea)from Uruguay.Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Pal?ontologie Monatshefte,2005: 641-662.

Heckert, A.B., Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., 2000.Specimens ofGomphotheriumin the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science and the species-level taxonomy of North AmericanGomphotherium.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 16: 187-194.

Hilgen, F.J., Lourens, L.J., Van Dam, J.A., 2012.The Neogene Period.In: Gradstein, F.M., Ogg, J.G., Schmitz, M., Ogg, G., (eds).The geologic time scale 2012 volume 2.Elsevier, 923-978.

Hoffstetter, R., 1950.Observaciones sobre los mastodontes de Sud América y especialmente del Ecuador.Haplomastodonsubgen.nov.deStegomastodon.Publicaciones de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional, 1: 1-39.

Hoffstetter, R., 1952.Les mammifères Pléistocènes de la République de l′équateur.Mémoires Societe Géologique de France, Nouvelle Série, 31: 1-391.

Hoffstetter, R., 1955.Remarques sur la classification et la phylogénie des mastodontes sud-américains.Bulletin de la Musum National d′Histoire Naturelle, 27: 484-491.

Holland, W.J., 1920.Fossil mammals collected at Pedra Vermelha,Bahia, Brazil, by G.A.Waring.Annals of the Carnegie Museum,13: 224-232.

Hulbert, R.C.Jr., 2001.The fossil vertebrates of Florida.Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1-350.

Joleaud, L., 1939.Atlas de paléobiogéographie.Paris: Paul Lechevalier, 39 (and 99 plates).

Kurtén, B., Anderson, E., 1980.The Pleistocene Mammals of North America.New York: Columbia University Press, 1-442.

Lambert, W.D., 1996.The biogeography of the gomphotheriid proboscideans of North America.In: Shoshani, J., Tassy, P., (eds).The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 143-148.

Lambert, D.W., Shoshani, J., 1998.Proboscidea.In: Janis, C., Scott,K., Jacobs, L.L., (eds).Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America.Volume 1.Terrestrial Carnivores, Ungulates and Ungulate-like Mammals.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,606-621.

Latrubesse, E.M., Rancay, A., 1998.The late Quaternary of the Upper Jurua River, southwestern Amazonia, Brazil: Geology and vertebrate paleontology.Quaternary of South America and Antarctic Peninsula, 11: 27-46.

Latrubesse, E.M., da Silva, S.A.F., Cozzuol, M., Absy, M.L., 2007.Late Miocene continental sedimentation in southwestern Amazonia and its regional significance: Biotic and geological evidence.Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 23: 61-80.

Latrubesse, E.M., Cozzuol, M., da Silva-Caminha, S.A.F., Rigsby,C.A., Absy, M.L., Jaramillo, C., 2010.The late Miocene paleogeography of the Amazon Basin and the evolution of the Amazon River system.Earth-Science Reviews, 99: 99-124.

Laurito, C.A., 1988.Los proboscídeos fósiles de Costa Rica y su contexto en la América Central.Vínculos, 14: 29-58.

López, G., Reguero, M., Lizuain, A., 2001.El registro más antiguo de mastodontes (Plioceno tardío)de América del Sur.Ameghiniana, 38(S): 35R-36R.

Lucas, S.G., 2008a.Cuvieronius(Mammalia, Proboscidea)from the Neogene of Florida.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 44: 31-38.

Lucas, S.G., 2008b.Taxonomic nomenclature ofCuvieroniusandHaplomastodon, proboscideans from the Plio-Pleistocene of the New World.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 44: 409-415.

Lucas, S.G., 2009a.Case 3480Mastodon waringi(currentlyHaplo?mastodon waringi; Mammalia, Proboscidea): Proposed conservation of usage by designation of a neotype.Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 66: 164-167.

Lucas, S.G., 2009b.Case 3479Cuvieronius(Mammalia, Proboscidea): Proposed conservation.Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 66: 1-6.

Lucas, S.G., Aguilar, R.H., Spielmann, J.A., 2011a.Stegomastodon(Mammalia, Proboscidea)from the Pliocene of Jalisco, Mexico and the species-level taxonomy ofStegomastodon.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 53: 517-553.

Lucas, S.G., Alvarado G.E., 2010.Fossil Proboscidea from the up-per Cenozoic of Central America: taxonomy, evolutionary and paleobiogeographic significance.Revista Geológica de América Central, 42: 9-42.

Lucas, S.G., Alvarado, G.E., 1994.The role of Central America in land-vertebrate dispersal during the Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic.Profil, 7: 401-412.

Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., 2005.Ice age proboscideans of New Mexico.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 28: 255-261.

Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., 2008.Taxonomy ofRhynchotherium(Mammalia, Proboscidea)from the Miocene-Pliocene of North America.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 44: 71-87.

Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., Estep, J.W., 2000.Biochronological significance of the co-occurrence of the proboscideansCuviero?nius,Stegomastodon, andMammuthusin the lower Pleistocene of southern New Mexico.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 16: 209-216.

Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., Estep, J.W., Mack, G.H., Hawley, J.W.,1999.Co-occurrence of the proboscideansCuvieronius,Stego?mastodon, andMammuthusin the lower Pleistocene of southern New Mexico.Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19: 595-597.

Lucas, S.G., Morgan, G.S., Spielmann, J.A., Pasenko, M.R., Aguilar, R.H., 2011b.Taxonomy and evolution of the Plio-Pleistocene proboscideanStegomastodonin North America.Current Research in the Pleistocene, 28: 173-175.

Madden, C.T., 1980.The Proboscidea of South America.Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 12: 474.

Montellano-Ballesteros, M., 2002.NewCuvieroniusfinds from the Pleistocene of central Mexico.Journal of Paleontology, 76: 578-583.

Morgan, G.S., 2005.The great American biotic interchange in Florida.Bulletin Florida Museum of Natural History, 45: 271-311.

Mothé, D., Avilla, L.S., Cozzuol, M.A., Winck, G.R., 2012a.Taxonomic revision of the Quaternary gomphotheres (Mammalia:Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae)from the South American lowlands.Quaternary International, 276-277: 2-7.

Mothé, D., Avilla, L.S, Cozzuol, M.A., 2012b.The South American gomphotheres (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae):Taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography.Journal of Mammalian Evolution, doi: 10.1007/s10914-012-9192-3.

Osborn, H.F., 1923.New subfamily, generic, and specific stages in the evolution of the Proboscidea.American Museum Novitates,99: 1-4.

Osborn, H.F., 1926.Additional new genera and species of the mastodontoid Proboscidea.American Museum Novitates, 238: 1-16.

Osborn, H.F., 1936.Proboscidea Volume I: Moeritheroidea Deinotheroidea Mastodontoidea.New York: The American Museum Press, 1-802.

Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., 2008.A cladistic analysis among trilophodont gomphotheres.Palaeontology, 51: 903-915.

Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., Azanza, B., Sanchez, B., Frassinetti,D., 2005.The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea)from South America.Quaternary International, 126-128: 21-30.

Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., Gómez, G., 2002.Late Pleistocene gomphotheres (Proboscidea)from the Arroyo Tapalque locality(Buenos Aires, Argentina)and their taxonomic and biogeographic implications.Neues Jahrbuch für Pal?ontologie und Geologie Abhandlungen, 225: 275-296.

Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., Sanchez, B., Aranza, B., 2003.Diversity of the Pleistocene gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea)from South America.Deinsea, 9: 347-363.

Proa?o, J.F., 1922.La Virgen del Dios Chimborazo, tradiciones puruhaes.Impresa El Observador, 1-23.

Prothero, D.R., Davis, E.B., Hopkins, S.S.B., 2008.Magnetic stratigraphy of the Massacre Lake Beds (late Hemingfordian,Miocene), northwest Nevada, and the age of the “proboscidean datum” in North America.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 44: 239-246.

Prothero, D.R., Dold, P.E., 2008.Magnetic stratigraphy of the Hemingfordian-Barstovian (lower to middle Miocene)Martin Canyon and Pawnee Creek formations, northeastern Colorado,and the age of the “proboscidean datum” in the High Plains.New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 44:247-254.

Reguero, M.A., Candela, A.M., Alonso, R.N., 2007.Biochronology and biostratigraphy of the Uquia Formation (Pliocene-early Pleistocene, NW Argentina)and its significance in the great American biotic interchange.Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 23: 1-16.

Romero-Pittman, L., 1996.Paleontologia de vertebrados.República de Peru, Sector Energía y Minas Instituto Geológico Minero Metalúrgico Boletín, 81: 174-177.

Sánchez, B., Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., 2003.Paleodiet, ecology,and extinction of Pleistocene gomphotheres (Proboscidea)from Pampean región (Argentina).Coloquios de Paléontologia, 1:617-625.

Sánchez, B., Prado, J.L., Alberdi, M.T., 2004.Feeding ecology,dispersal, and extinction of South American Pleistocene gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea).Paleobiology, 30:146-161.

Savage, D., 1955.A survey of various late Cenozoic faunas of the Panhandle of Texas, part II: Proboscidea.University of California Publications in Geological Sciences, 31: 51-74.

Shoshani, J., Tassy, P., 1996.Summary, conclusions, and a glimpse into the future.In: Shoshani, J., Tassy, P., (eds).The Proboscidea:Evolution and palaeoecology of elephants and their relatives.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 335-348.

Shoshani, J., Tassy, P., 2005.Advances in proboscidean taxonomy &classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior.Quaternary International, 126-128: 5-20.

Simpson, G.G., Paula Couto, C., 1957.The mastodons of Brazil.Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 112: 125-190.

Simpson, G.G., Paula Couto, C., 1981.Fossil mammals from the Cenozoic of Acre, Brazil III—Pleistocene Edentata Pilosa, Pro-boscidea, Sirenia, Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla.Iheringia, 6:11-73.

Tassy, P., 1996.The earliest gomphotheres.In: Shoshani, J., Tassy,P., (eds).The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives.Oxford: Oxford University Press,89-91.

Tedford, R.H., Albright, L.B.I., Barnosky, A.D., Ferrusquia-Villafranca, I., Hunt, R.M.Jr., Storer, J.E., Swisher, C.C.I.,Voorhies, M.R., Webb, S.D., Whistler, D.P., 2004.Mammalian biochronology of the Arikareean through Hemphillian interval(late Oligocene through early Pliocene epochs).In: Woodburne,M.O., (ed).Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America.New York: Columbia University Press, 169-231.

Teilhard, P., Traessert, M., 1937.The proboscideans of south-eastern Shansi.Palaeontologia Sinica, Series C, 13: 1-58.

Tobien, H., 1973.On the evolution of mastodonts (Proboscidea,Mammalia).Part 1: The bunodont trilophodont groups.Hessisches Landesamt für Bodenforschung Wiesbaden, 101: 202-276.

Tobien, H., 1978.On the evolution of the mastodonts (Proboscidea,Mammalia).Part 2: The bunodont tetralophodont groups.Geologisches Jahrbuch Hessen, 106: 159-208.

Tobien, H., Chen, G., Li, Y., 1986.Mastodonts (Proboscidea, Mammalia)from the late Neogene and early Pleistocene of the People′s Republic of China Part 1 Historical account; the generaGomphotherium,Coerolophodon,Synconolophus,Amebelodon,Platybelodon,Sinomastodon.Mainzer Geowissenschaftliche Mitteilungen, 15 : 119-181.

Webb, S.D., 1992.A brief history of New World Proboscidea with emphasis on their adaptations and interactions with man.In: Fox,J.W., Smith, C.B., Wilkins, K.T.(eds).Proboscidean and Paleoindian Interactions.Baylor University Press, 16-34.

Webb, S.D., Dudley, J.P., 1995.Proboscidea from the Leisy Shell Pits, Hillsborough County, Florida.Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, 37: 645-660.

Webb, S.D., Perrigo, S.C., 1984.Late Cenozoic vertebrates from Honduras and El Salvador.Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology,4: 237-254.

Woodburne, M.O., 2010.The great American biotic interchange:Dispersals, tectonics, climate, sea level and holding pens.Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 17: 245-264.

Woodburne, M.O., Cione, A.L., Tonni, E.P., 2006.Central American provincialism and the great American biotic interchange.In: Carranza-Castaneda, ó., Lindsay, E.H., (eds).Advances in Late Tertiary Vertebrate Paleontology in Mexico and the Great American Biotic Interchange.Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología and Centro de Geociencias,Publicación Especial, 4: 73-101.

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年1期

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年1期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Facies-succession and architecture of the thirdorder sequences and their stratigraphic framework of the Devonian in Yunnan-Guizhou-Guangxi area,South China

- Mesozoic lithofacies palaeogeography and petroleum prospectivity in North Carnarvon Basin, Australia

- Classifications, sedimentary features and facies associations of tidal f lats

- Review of research in internal-wave and internal-tide deposits of China

- The response of deltaic systems to climatic and hydrological changes in Daihai Lake rift basin,Inner Mongolia, northern China

- Palaeobiogeographical constraints on the distribution of foraminifers and rugose corals in the Carboniferous Tindouf Basin, South Morocco