Mesozoic lithofacies palaeogeography and petroleum prospectivity in North Carnarvon Basin, Australia

Tao Chongzhi , Bai Guoping , , Liu Junlan , Deng Chao , Lu Xiaoxin, Liu Houwu,Wang Dapeng

1.State Key Laboratory of Petroleum Resources and Prospecting, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing 102249, China

2.Basin and Reservoir Research Center, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing 102249, China

3.SinoChem Petroleum Exploration & Production Co., Ltd., Beijing 100031, China

4.Wireline Logging Company of GWDC, Panjin, Liaoning 124010, China

1 Introduction*

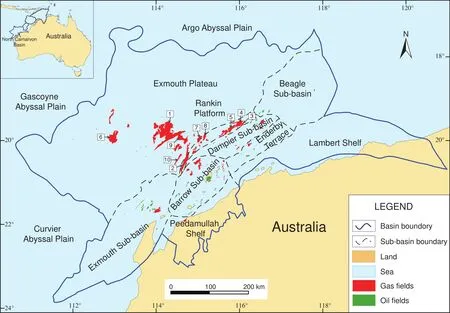

The North Carnarvon Basin is a large sedimentary basin located in the southern part of the North West Shelf of Australia.It extends more than 1000 km along the western and northwestern coastline of Western Australia,covering an area of 54.44×104km2, only with 0.94×104km2being onshore.The basin is the premier petroliferous basin in Australia with most of its discovered hydrocarbons reservoired in the Mesozoic.By the end of 2009,201 discoveries had been made in the basin with initial 2P recoverable oil reserves of 376.3×106m3, gas reserves of 33,302.0×108m3, condensate reserves of 259.9×106m3.The total oil equivalent is 3,752.8×106m3, of which 83.1%is gas.The exploration has now entered into the moderate to high mature stages.What explorers and researchers of this area are commonly concerned about is finding more potential prospects.The success of future exploration depends not only on the application of more advanced exploration technologies, but also on fundamentally theoretical research.In the Gulf of Mexico, for example, the latter have been proved to be indispensable for obtaining the deep and ultra-deep water petroleum exploration breakthroughs.

This paper focuses on the Mesozoic lithofacies palaeogeography and petroleum prospectivity in the North Carnarvon Basin.Chinese practices have shown that the lithofacies palaeogeographic research is an effective theoretical means to guide petroleum exploration by studying the sedimentary environment of source rocks, the distribution of reservoir facies and the development of seals.(e.g., Fenget al., 1997; Liuet al., 2003; Zhuet al., 2004;Feng, 2009).Like their Chinese colleagues, Australian re-searchers have also conducted similar studies for the North Carnarvon Basin and compiled some lithofacies palaeogeographical maps.For example, Bradshawet al.(1988)compiled schematic lithofacies palaeogeographic maps of the entire North West Shelf based on palaeontological and stratigraphic data.On their maps, they demarcated the areas of continental, marine and coastal environments.Then Bradshawet al.(1998)and Longleyet al.(2002)likewise compiled the lithofacies palaeogeographic maps of the entire shelf with the theoretical guidance of the sedimentology, stratigraphy, geophysics and tectonics.Hocking(1988)described the lithofacies palaeogeography of the North Carnarvon Basin, but focused only on the Barrow,Dampier and Exmouth Sub-basins.These previous studies and the newly obtained data from petroleum exploration in the last ten years provide the fundamental data base for our research.

Although the “single factor analysis and multifactor comprehensive mapping method” proposed by Feng (1992,1999, 2003, 2004, 2009)has been proved to be effective in compiling lithofacies palaeogeographic maps, but due to a lack of first-hand outcrop, core, drill cutting, mud logging,and wireline log data, it could not be applied in our study.Therefore, our palaeogeographic work is chiefly to modify and refine the previous lithofacies palaeogeographic maps through compiling the comprehensive stratigraphic columns of the different stratigraphic successions and then integrating these columns with regional 2D seismic sections and tectonic balance profiles.

2 Geological setting

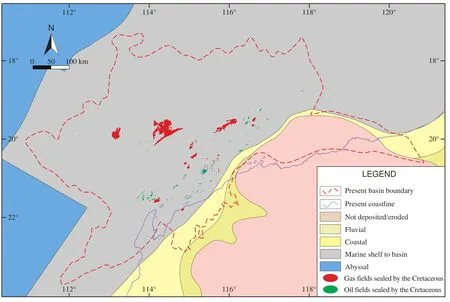

The North Carnarvon Basin is a Mesozic-Cenozoic passive marginal basin which evolved from a cratonic basin.The basin is mainly filled with Mesozoic sediments up to 15 km thick (Hocking, 1988).It is adjacent to the Roebuck Basin in the northeast and the Curvier, Gascoyne and Argo abyssal plains in the west and north (Fig.1).The main structural elements in the basin are NE-SW extended, parallel to the coastline of the North West Shelf (Fig.1).The inner area closer to the land is the Peedamullah Shelf and the Lambert Shelf.Sub-basins and terraces occur in the central zone, including the Exmouth, Barrow, Dampier and Beagle Sub-basins and the Enderby Terrace.The outer area is occupied with the Exmouth Plateau and the Rankin Platform (Fig.1).

The tectonic evolution of the North Carnarvon Basin is closely related to the breakup and separation of Gondwanaland.It experienced the pre-rifting, early rifting, main rifting, late rifting, post-rifting sagging and passive margin stages (AGSO, 1994; Stagg and Colwell, 1994).During the Late Permian to Triassic pre-rifting stage, the structural activities were dominated by sagging subsidence.At the end of this stage, the Fitzroy tectonic event occurred and led to the formation of the Rankin Platform and its adjacent sub-basins.

The basin began rifting stage in the Early Jurassic(Pliensbachian)and subsequently entered into the synrifting stage, which is subdivided into 3 phases.In the early rifting phase, extensional stress led to the formation of normal faults and NE-SW oriented tilted blocks, horsts and grabens (Barber, 1988).The basin went into the main rifting phase in the Middle Jurassic (Callovian)when continental breakup began along the northern margin of the Exmouth Plateau (Jablonski, 1997).Thick marine mudstones were deposited continuously after the continental breakup, gradually filled the graben depocenters and onlapped the marginal highlands in the meantime (Tindaleet al., 1998).The breakup of the Indian-Australian Plate in Middle Tithonian marked the beginning of the late rifting phase when faults were reactivated in the basin (Heartyet al., 2002).

In the Valanginian time, the continental breakup first started along the margin of the Curvier and the Gascoyne abyssal plains southwest of the Exmouth Plateau (Hocking, 1990; Jablonski and Saitta, 2004).This tectonic event marked the end of the rifting stage.Then the basin entered into the post-rifting sagging stage when regional subsidence was dominant, led to the deposition of a set of transgressive clastic rocks.This stage ceased in the Mid-Santonian.Afterwards, the entire region became cold and subsided continuously.The basin passed into the passive margin stage.A set of stratigraphic units dominated by carbonates were deposited.In the Miocene time, the collision of the Australian-Indian Plate with the Eurasia Plate caused tilting, inversion, and the reactivation of faults(Longleyet al., 2002; Cathro and Karner, 2006).

3 Mesozoic lithofacies palaeogeography

3.1 The Triassic lithofacies palaeogeography

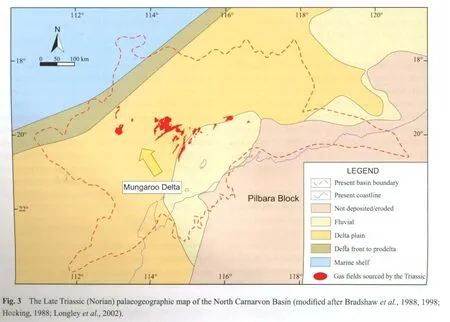

The Triassic sediments are distributed widely within the North Carnarvon Basin.A NE-SW trending depocenter zone was largely controlled by faults and hinge lines.The sedimentary succession includes a Lower Triassic marine transgressive sequence, a Middle Triassic marine regres-sive sequence, and an Upper Triassic marine transgressive sequence.As a result, the Triassic sediments comprise a complete depositional cycle (Fig.2).

Fig.1 Map showing the structural subdivision and the field distribution in the North Carnarvon Basin.The 10 giant gas fields are labeled from large to small scale according to the reserve size: 1-Jansz; 2-Gorgon; 3-North Rankin; 4-Perseus; 5-Goodwyn; 6-Scarborough; 7-Pluto; 8-Wheatstone 1; 9-Geryon 1; and 10-Clio 1.

The regional transgression resulting from the pre-rifting sagging commenced at the beginning of the Triassic.Marine shales were extensively deposited over the entire North West Shelf (Bradshawet al., 1988, 1998).These sediments are 200-1000 m thick and contain the same fossils.In the North Carnarvon Basin, the deposited shales comprise the Locker Shale (Fig.2).

The marine regression began at the end of the Early Triassic and peaked in the Middle Triassic.It was followed by a marine transgression of the Late Triassic when the coastal line gradually onlapped the onshore area.The transgression proceeded slowly and was less extensive than the Early Triassic marine transgression.During the Middle to the Late Triassic, the Mungaroo fluvio-deltaic depositional system prograded northwestwards and covered most of the North Carnarvon Basin (Fig.3).It led to the deposition of the Mungaroo Formation with a thickness of several kilometers.The formation consists of interbedded quartz sandstones, siltstones, shales, and coal beds.It constitutes the principal reservoir intervals for gas and condensate in the Exmouth Plateau and the Rankin Platform (Bai and Yin, 2007).Throughout most of the Triassic, the present day onshore part of the North Carnarvon Basin and the adjacent Pilbara Block underwent active uplifting and erosion (Fig.3), supplying abundant sediments for the deposition of the Locker Shale and the Mungaroo Formation.At the end of the Triassic, the abundant sediment supply was terminated by the Fitzroy tectonic movement (Hocking, 1990).

3.2 The Jurassic lithofacies palaeogeography

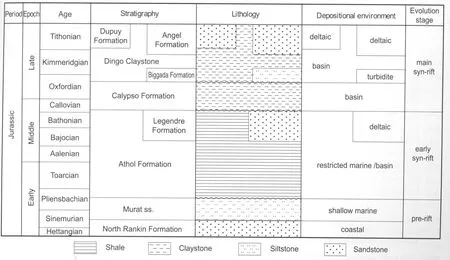

The Jurassic is a period when the tectonic setting in the North Carnarvon Basin changed from rifting to continental breakup and seafloor spreading.This change of tectonic setting influenced the depositional pattern of the Jurassic(Fig.4).The Exmouth, Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins were the active depocenters (Longleyet al., 2002).Com-

pared with other Mesozoic sedimentary strata which have a blanket distribution pattern, the Jurassic sediments have a limited distribution and a highly variable thickness.In the depocenters of the Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins they are over 6 km thick, while in the Rankin Platform and the Exmouth Plateau they are absent or only a few to tens of meters thick (Bradshawet al., 1988).

During the Jurassic, the North West Shelf was located on the south margin of the Neo-Tethys Ocean, belonging to the intermediate latitude range.The climate inherited the seasonal drought feature of the Middle-Late Triassic,but it was humid enough to sustain large fluvial depositional systems and local deposition of coal beds.

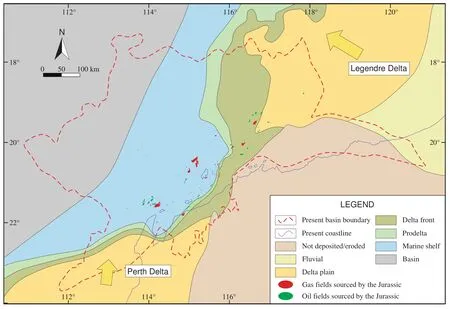

In the Early Jurassic, the depositional style inherited that of the Triassic.The present day onshore part was still the dominant erosional area.Shallow marine and transitional facies covered most of the basin (Fig.5).Deltaic sandstones of the Legendre Formation (Fig.4)were deposited in the eastern part of the basin, namely, the Legendre Delta on the north and the Perth Delta on the south (Fig.5).The proto Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins started to subside because of the previous rifting, and were filled with marine claystone of the Athol Formation locally (Fig.4).

Sea-floor spreading in the Callovian promoted the continental break-up, which changed the landform and hence the depositional pattern in the North Carnarvon Basin (Fig.6).The Rankin Platform was uplifted and eroded or received little deposition.Fine clastics dominated by deep water shelf and basin facies shales were deposited in the Exmouth, Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins (Fig.6), and they constitute the Calypso Formation (Fig.4).The erosion associated with the Callovian unconformity supplied clastics to the Dampier Sub-basin, leading to the deposition of turbidite sands of the Biggada Formation encased within the Dingo Claystone (Fig.4).

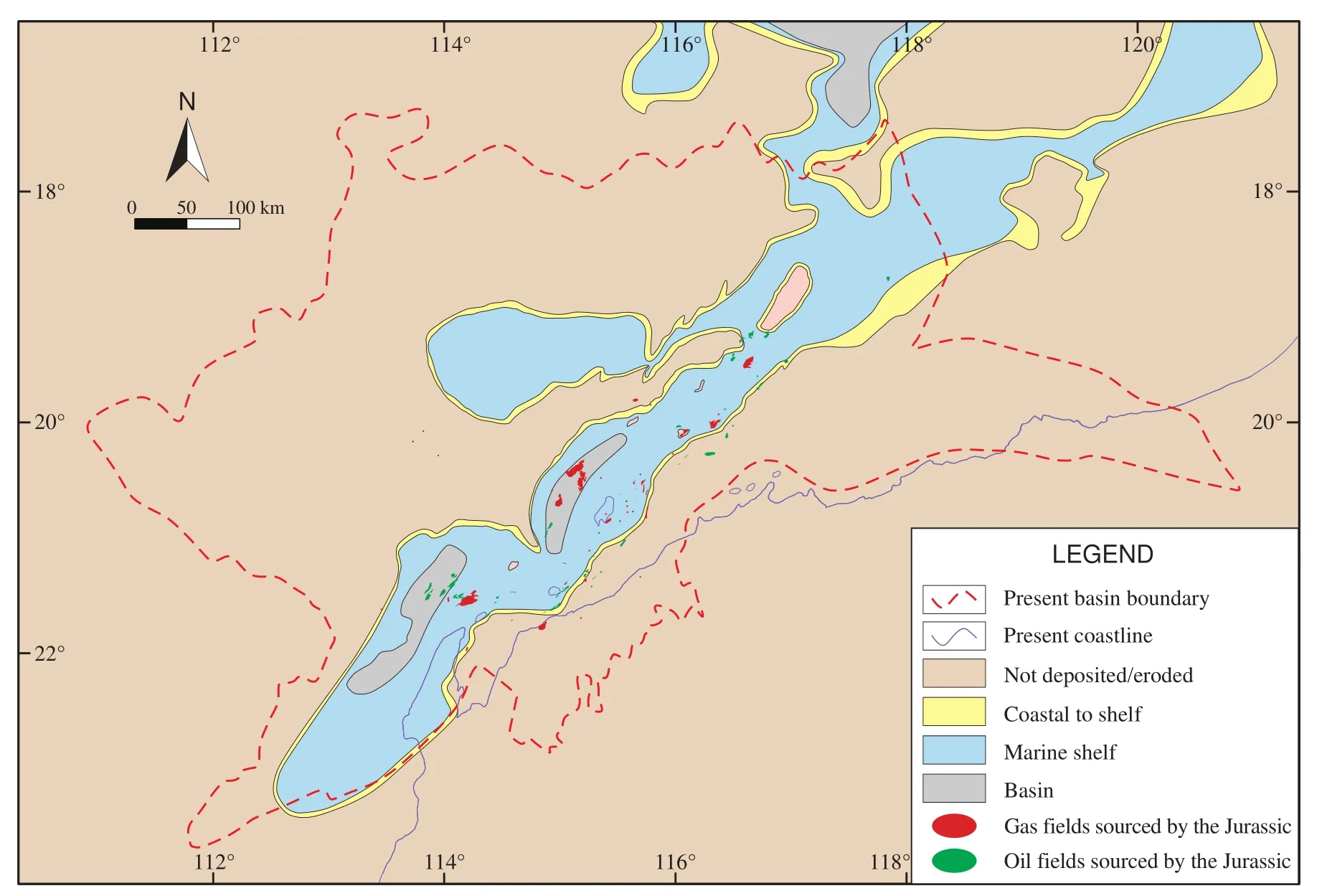

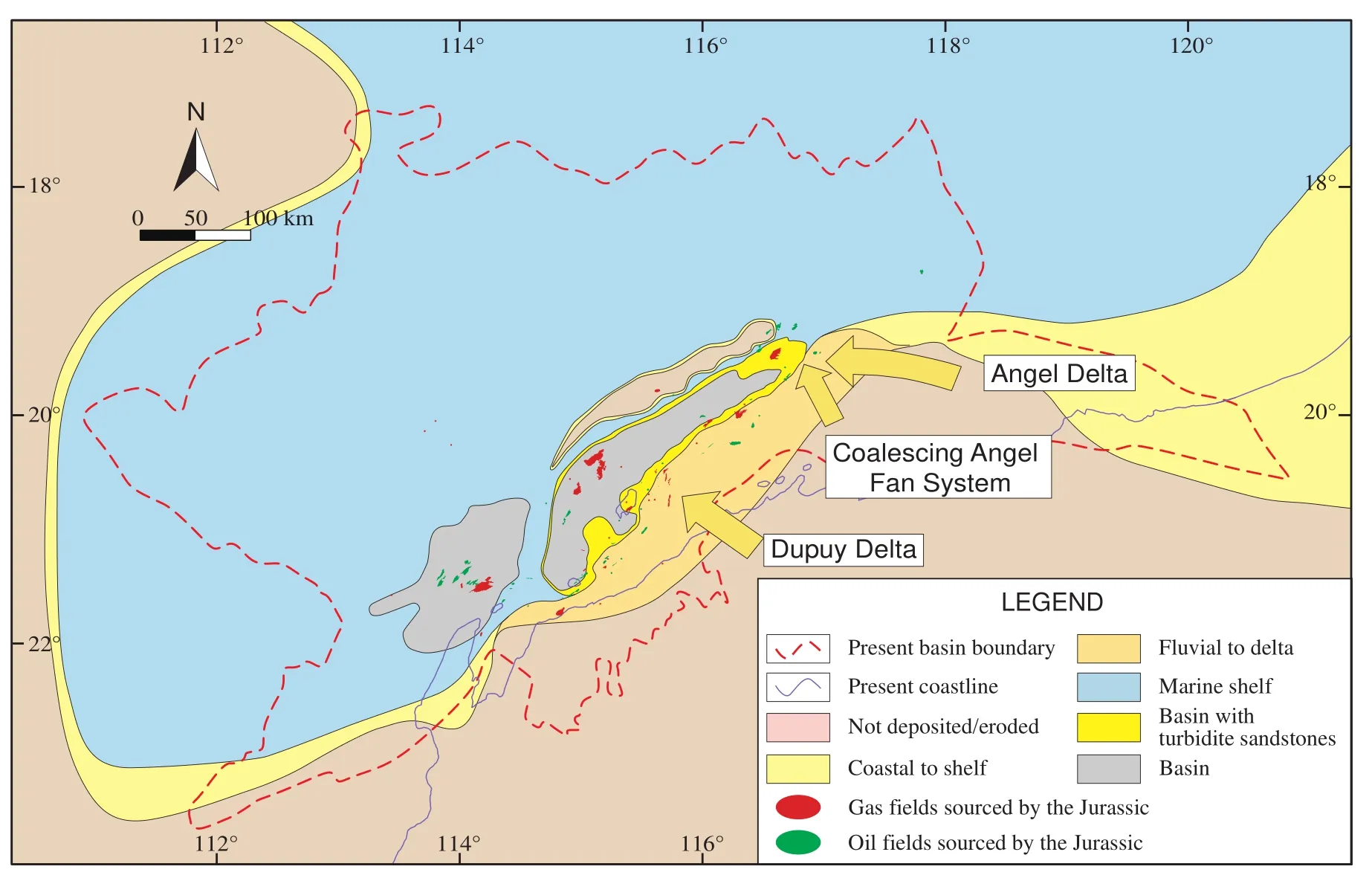

From the Oxfordian to the Tithonian, owing to sea-floor spreading in the Argo abyssal plain, structural subsidence and detrital supply waned.The basin was connected with the deep ocean in the Late Jurassic.The sea level rising led to the deepening of sea water, and the Exmouth, Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins became active depocenters (Fig.7).As a result, continuous and thick deep marine basinal Dingo Claystone (Fig.5)was deposited in these sub-basins.The shelf facies was deposited mainly in other parts of the basin.The Dupuy and Angel Deltas were deposited along the present day′s coastal line in the Early Tithonian(Fig.7).

3.3 The Cretaceous lithofacies palaeogeography

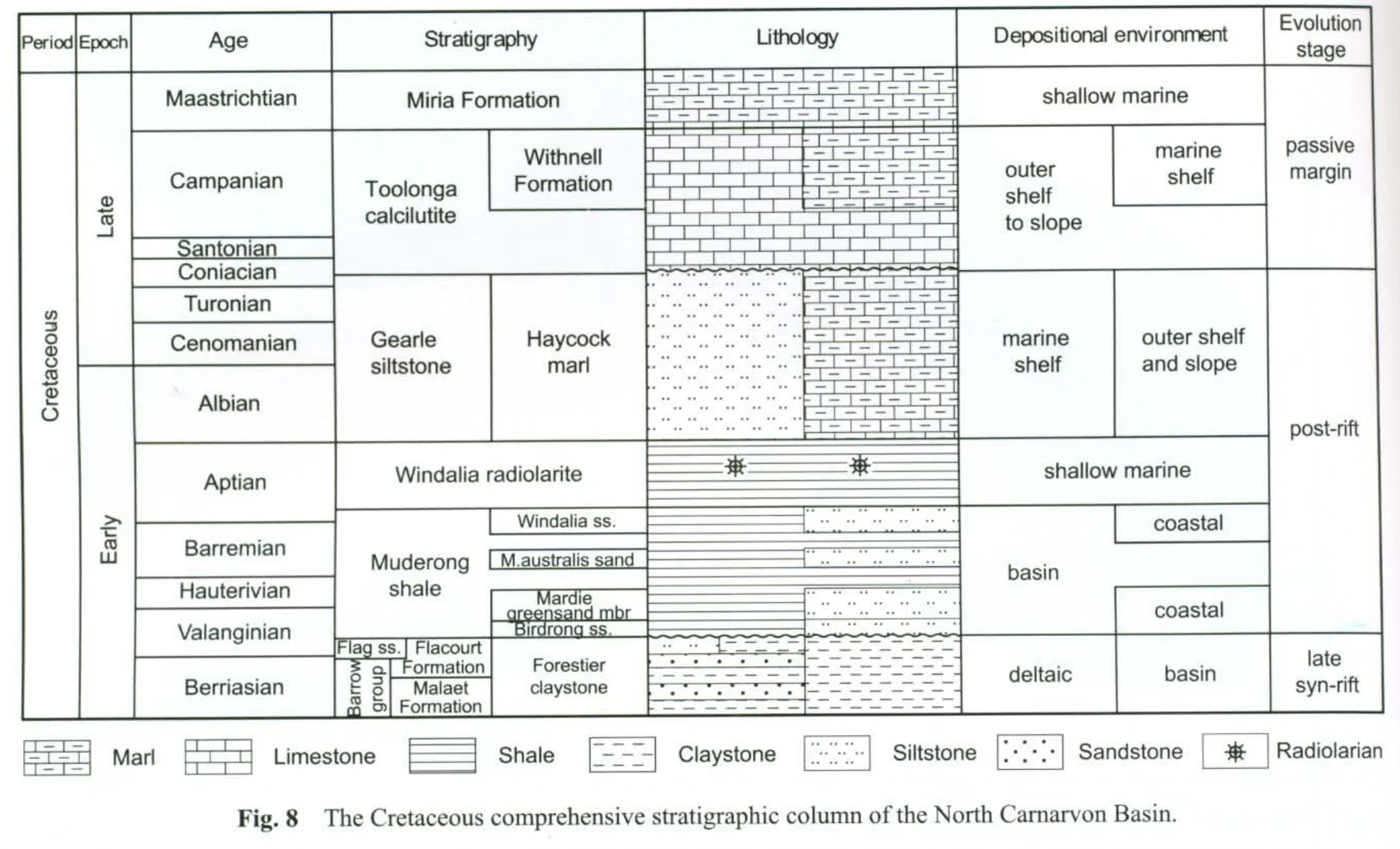

Compared with the limited distribution of the Jurassic syn-rift sediments, the Cretaceous strata are more widely distributed, but are thinner.They were deposited on thepre-existing faulted uplifts, covered structural highs such as the Rankin Platform, and extended towards the present day′s onshore part.Throughout the Cretaceous, climate was warming.The Lower Cretaceous consists of deltaic sandstone and marine shale and the Upper Cretaceous is dominated by carbonate rocks (Fig.8).

Fig.4 The Jurassic comprehensive stratigraphic column of the North Carnarvon Basin.

Fig.5 The Early to Middle Jurassic palaeogeographic map of the North Carnarvon Basin (modified after Bradshaw et al., 1988, 1998;Hocking, 1988; Longley et al., 2002).

Fig.6 The Callovian palaeogeographic map of the North Carnarvon Basin (modified after Bradshaw et al., 1988, 1998; Hocking,1988; Longley et al., 2002).

Fig.7 The Early Tithonian palaeogeographic map of the North Carnarvon Basin (modified after Bradshaw et al., 1988, 1998; Hocking, 1988; Longley et al., 2002).

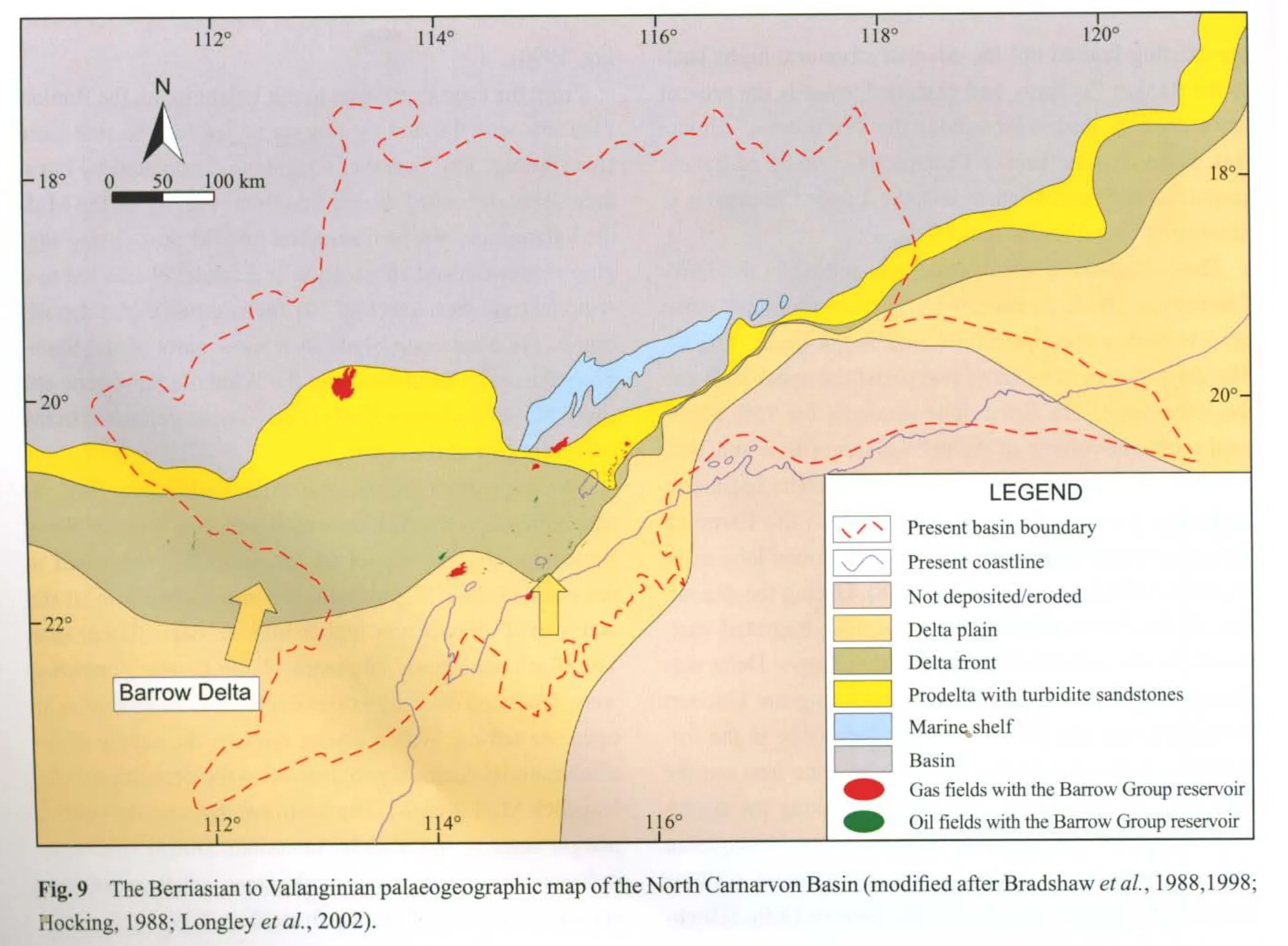

The basin was in a stable tectonic setting in the Early Cretaceous.The large Barrow Delta system was deposited quickly over a short period of time in the basin (Fig.9).The delta system consists of two parts: the upper lobe and the lower lobe.The lower lobe accounts for 75% of the total sediment volume of the delta system (Ross and Vail,1994).In the Berriasian time, the Barrow Delta sediments prograded from the Exmouth Sub-basin to the Exmouth Plateau, which led to the formation of the lower lobe making up the Malouet Formation (Fig.8).During the deposition of the Barrow Delta, the depocenter migrated eastwards.In the Late Berriasian time, the Barrow Delta was retrograding and the upper lobe constituting the Flacourt Formation was laid down.The Flag Sandstone in the formation consists of turbidites fed by submarine fans and the delta (Fig.8).The continental break up along the southwest margin of the Exmouth Plateau in the Valanginian time broke down the large distributary channel systems and ended sediment supply for the Barrow Delta (Hocking, 1990).

From the Late Berriasian to the Valanginian, the Rankin Platform was flooded by marine water for the first time since rifting.The Forestier Claystone dominated by basin facies was deposited during this time (Fig.8).In the Middle Valanginian, the basin entered into the post-rifting sagging phase.Crustal subsidence and sea level rise led to a regional transgression (Fig.10)and resulted in the deposition of the Muderong Shale over most parts of the basin.The Maustralis Sandstone and the Windalia Sandstone encased in the Muderong Shale (Fig.8)were deposited in the southeast part of the basin.

The deposition of the Windalia Radiolarite (Fig.8)was initiated in the Aptian, which indicates that the ocean started to have an impact on the sediments deposited in the basin.In the Mid-Albian, the subsidence rate of the continental margin was higher than its depositional rate.The black shales and siltstones of the Gearle Formation were deposited over the earlier Cretaceous sediments in an open sea setting.With a drying climate, the supply of detrital material declined and thus led to the deposition of the Haycock Marl (Fig.8).The basin entered into the passive margin stage in the Middle Santonian.During this stage,sediments are dominated by carbonates, which constitute a sedimentary wedge thinning from SE to NW.

Fig.10 The Valanginian to Barremian palaeogeographic map of the North Carnarvon Basin (modified after Bradshaw et al., 1988,1998; Hocking, 1988; Longley et al., 2002).

4 Discussion

4.1 The Triassic rocks as principal gas source rocks

Under the warm and humid conditions in the Triassic time, two sets of source rocks were deposited in the North Carnarvon Basin.They are the Lower Triassic Locker Shale of marine origin and fluvial-deltaic coal measures and carbonaceous shales of the Middle-Upper Triassic Mungaroo Formation.Up to now, few boreholes have been drilled to the deeply buried Locker Shale.However,the modeling of hydrocarbon generation indicates that the Locker Shale has a gas generating potential (Hockinget al., 1988).Fluvial-deltaic sediments in the Mungaroo Formation mainly contain gas-prone humic organic matter.Geochemical analyses suggest that giant gas fields (The giant field refers to the field with a recoverable reserves of at least 3 trillion cubic feet, TCF)discovered so far in the Exmouth Plateau and the Rankin Platform are all sourced by the Mungaroo Formation.The Triassic source rocks are mostly buried deeply and are currently mature or overmature for oil generation.The humic kerogen type and the deep burial depth led to the determination that the Triassic source rocks acted as the gas source rocks in the basin.

Petroleum systems analyses indicate that the reserves of oil and gas derived from the Mungaroo Formation account for 74% of the total reserves of 2778.3×106m3oil equivalent in the basin, of which 91.8% are gas.Of the 201 fields discovered in the basin, 52 fields are sourced by the Triassic rocks.They tend to have large reserve sizes and are mostly distributed in the Rankin Platform and the Exmouth Plateau (Fig.3).Gas from each of the 10 giant gas fields in the basin were derived from the Triassic source rocks.Therefore, it can be affirmed that the Triassic rocks should be very important gas source rocks in the basin.

4.2 The Upper Jurassic basinal shales as main oil source rocks

The Late Jurassic main rifting phase is when the thick basinal shales and mudstone of the Dingo Claystone were deposited in the depocenters of the basin.These depocenters correspond to the Exmouth, Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins (Fig.7).The Dingo Claystone is the dominant oil source rock interval in the basin and generates 98.7% of total oil reserves of 371.3×106m3in the North Carnarvon Basin.The hydrocarbons generated by the Dingo Claystone migrated chiefly in a vertical mode, with the lateral migration paths being very short.Thus, most of the oil fields discovered are located within the sub-basins, with only a smaller amount of hydrocarbons migrating updip into the Enderby Terrace to form oil accumulations (Fig.7).Therefore, it is proposed that the distribution of the Upper Jurassic basinal source rocks controlled the regional distribution of discovered oil fields in the North Carnarvon Basin.Outside of the depocenters, the Upper Jurassic is very thin and deposited under a shallow water environment which is unfavorable for the formation of high quality oil source rocks (Fig.7).For instance, shallow marine sandstones in the Upper Jurassic are the main reservoirs of the Jansz Gas Field (the largest field discovered in the basin)in the Exmouth Plateau (Jenkinset al., 2003), while there are no large discoveries in the Beagle Sub-basin where the high quality Upper Jurassic source rocks are absent (Fig.1).

4.3 Deltaic sediments as favorable reservoirs

There are a lot of the Mesozoic deltaic sandstones and delta-fed turbidites in the North Carnarvon Basin.They form important reservoirs in different stratigraphic intervals.

In the Middle-Late Triassic, the Mungaroo Delta covered a vast area in the basin (Fig.3).Fluvial-deltaic sandstones of the Mungaroo Formation make up important gas reservoirs in the North Carnarvon Basin.They are the principal reservoirs especially in the giant gas fields of Gorgon, Rankin North, Perseus and Geryon 1 in the Rankin Platform and the Exmouth Plateau (Fig.1).

In the early rifting phase, the deltaic sandstones in the Legendre Formation were deposited in the Legendre Delta on the north and Perth Delta on the south (Fig.5).They form important reservoirs in the Lower Jurassic.Sandstones deposited in the Angel Delta, including delta-fed turbidites, make up reservoirs in the Upper Jurassic in the Dampier Sub-basin (Fig.7).

In the earliest Cretaceous, delta-fed turbidite sandstones of the Flag Sandstone were deposited in front of the Barrow delta (Fig.9).They are the reservoirs of the Scarborough Gas Field in the Exmouth Plateau.The Lower Cretaceous deltaic sands and associated delta-fed turbidites constitute the important reservoirs for the oil fields in the basin.

Chinese studies of deltaic sediments by the sequence stratigraphic method show that turbidite fan sands, deltafed turbidite sands and fluvial sands constitute subtle traps in the Bohai Bay Basin (Li and Pang, 2003; Zhanget al.,2003; Bai and Zhang, 2004).The discovery of the giant Scarborough Gas Field with turbidite sands as reservoirs indicates that there might be a considerable potential for exploration of non-structural accumulations in the North Carnarvon Basin.With the improvement of offshore drilling technology, the increasing coverage of 3D seismic survey and the strengthening of the fine lithofacies palaeogeographic studies in the North Carnarvon Basin, we expect that more and more non-structural accumulations may be discovered in the basin.

4.4 The Lower Cretaceous shales as effective seals

In the Early Cretaceous, the tectonic setting changed from syn-rifting to post-rifting drifting, and the Lower Cretaceous Forestier Claystone and the transgressive Muderong Shale were deposited (Fig.10).The marine shales of the Muderong Shale are distributed throughout the entire basin and may extend beyond the present day′s boundary of the basin (Fig.10).The Muderong Shale has a maximum thickness of 900 m in the depocenters.Because of its extensive distribution and large thickness, it can provide effective preservation conditions for the underlying reservoirs.This regional cap rock seals not only the Lower Cretaceous reservoirs, but also the Jurassic and Triassic reservoirs, which are unconformably overlain by the Muderong Shale.The fields sealed by the Lower Cretaceous regional shale are distributed throughout the entire basin (Fig.10).It is the regional seal for the Upper Jurassic reservoirs in the Jansz Field, the Lower Cretaceous reservoirs in the Scarborough Field in the Exmouth Plateau, Triassic reservoirs in the Goodwyn Field in the Rankin Platform, and Lower Cretaceous-Upper Jurassic reservoirs in the fields in the four Sub-basins (Fig.10).The Cretaceous cap rocks dominated by the Muderong Shale have sealed 68.1% of the total oil and gas reserves in the North Carnarvon Basin.

5 Conclusions

1)The North Carnarvon Basin was in the pre-rifting cratonic sagging phase in the Triassic when fluvial-deltaic gas-prone source rocks of the Mungaroo Formation were deposited.The high maturity and humic kerogene type made the basin a gas-endowed basin.

2)Rifting took place in the Jurassic and its main phase occurred in the Late Jurassic.The oil source rocks of deepmarine basinal origin in the Dingo Claystone were deposited in the depocenters of the Exmouth, Barrow and Dampier Sub-basins.They controlled the regional distribution of oil accumulations in the basin.

3)The Early Cretaceous transgression led to the extensive deposition of the Muderong Shale.It constitutes the regional cap rock which sealed the underlying reservoirs effectively and also controlled the stratigraphic distribution of hydrocarbons.

4)The deltaic depositional systems played an important role in the formation of hydrocarbon accumulations in the North Carnarvon Basin.Further detailed studies of sequence stratigraphy and lithofacies palaeogeography will provide guidance for finding more and more non-structural hydrocarbon accumulations in deltaic sandbodies and delta-fed turbidite sands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Feng Zengzhao and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that have greatly improved the original manuscript.This study was financially supported by National Science and Technology Major Project of the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (No.2011ZX05031-001-007HZ).

AGSO (Australian Geological Survey Organization), North West Shelf Study Group, 1994.Deep reflection on the North West Shelf: Changing perceptions of basin formation.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 63-76.

Bai Guoping, Yin Jinyin, 2007.Petroleum geological features and exploration potential analysis of North Carnavon basin, Australia.Petroleum Geology & Experiment, 29(3): 253-258 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Bai Guoping, Zhang Shanwen, 2004.Depositional patterns and oil/gas accumulation features of Sha-3 Member turbidites in Dongying Depression, Bohai Bay Basin.Petroleum Science, 1(2):105-110.

Barber, P.M., 1988.The Exmouth Plateau deep water frontier: A case history.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The North West Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 173-187.

Bradshaw, J., Sayers, J., Bradshaw, M., Kneale, R., Ford, C., Spencer, L., Lisk, M., 1998.Palaeogeography and its impact on the petroleum systems of the North West Shelf, Australia.In: Purcell,P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia.Perth: WA, 95-121.

Bradshaw, M.T., Yeates, A.N., Beynon, R.M., Brakel, A.T., Langford, R.P., Totterdell, J.M., Yeung, M., 1988.Palaeogeographic evolution of the North West Shelf region.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The North West Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, Perth: WA,29-54.

Cathro, D.L., Karner, G.D., 2006.Cretaceous-Tertiary inversion history of the Dampier Sub-basin, northwest Australia: Insights from quantitative basin modeling.Marine and Petroleum Geology, 23(4): 503-526.

Feng Zengzhao, Li Shangwu, Yang Yuqing, Jin Zhenkui, 1997.Potential of oil and gas of the Permian of south China from the viewpoint of lithofacies paleogeography.Acta Petrolei Sinica,18(1): 10-17 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Feng Zengzhao, 1992.Single factor analysis and comprehensive mapping method-methodology of lithofacies paleogeography.Acta Sedimentologica Sinica, 10(3): 70-77 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Feng Zengzhao, 1999.Origin, development and future of palaeogeography of China.Journal of Palaeogeography, 1(2): 1-7 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Feng Zengzhao, 2003.Origin, development, problems and common viewpoint of palaeogeography of China.Journal of Palaeogeography, 5(2): 129-141 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Feng Zengzhao, 2004.Single factor analysis and multifactor comprehensive mapping method——reconstruction of quantitative lithofacies palaeogeography.Journal of Palaeogeography, 6(1):3-19 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Feng Zengzhao, 2009.Definition, content, characteristics and bright spots of palaeogeography of China.Journal of Palaeogeography,11(1): 1-11 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Hearty, D.J., Ellis, G.K., Webste, K.A., 2002.Geological history of the western Barrow Sub-basin: implications for hydrocarbon entrapment at Woollybutt and surrounding oil and gas fields.In:Keep, M., Moss, S.J., (eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia 3: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 577-598.

Hocking, R.M., 1988.Regional geology of the North Carnarvon basin.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The North West Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 97-114.

Hocking, R.M., 1990.Carnarvon Basin, geology and mineral resources of Western Australia.Western Australia Geological Survey Memoir 3: 457-495.

Jablonski, D., Saitta, A.J., 2004.Permian to Lower Cretaceous plate tectonics and its impact on the tectonostratigraphic development in the Western Australia margin.The APPEA Journal, 44(1):287-327.

Jablonski, D., 1997.Recent advances in the sequence stratigraphy of the Triassic to Lower Cretaceous succession in the northern Carnarvon Basin, Australia.The APPEA Journal, 37(1): 429-454.

Jenkins, C.C., Maughan, D.M., Acton, J.H., Duckett, A., Korn, B.E., Teakle, R.P., 2003.The Jansz Gas Field, Carnarvon Basin,Australia.The APPEA Journal, 43(1): 303-324.

Li Peilong, Pang Xiongqi, 2003.The formation of subtle reservoir in continental fault basin-A case study in Jiyang depression.Beijing: Petroleum Industry Press, 1-426 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu Luofu, Zhu Yixiu, Xiong Zhengxiang, Sun Jianping, Chen Lixin,Zhu Shengli, Kong Xiangyu, 2003.Characteristics and evolution of lithofacies palaeogeography in Pre-Caspian basin.Journal of Palaeogeography, 5(3): 279-290 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Longley, I.M., Buessenschuett, C., Clydsdale, L., Cubitt, C.J., Davis, R.C., Johnson, M.K., Marshall, N.M., Somerville, A.P.R., Spry, T.B., Thompson, N.B., 2002.The North West Shelf of Australia-A Woodside perspective.In: Keep, M., Moss, S.J.,(eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia 3: Proceedings of the Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 27-88.

Ross, M.I., Vail, P.R., 1994.Sequence stratigraphy of the Lower Neocomian Barrow Delta, Exmouth Plateau, Northwestern Australia.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R., (eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 435-447.

Stagg, H.M.J., Colwell, J.B., 1994.The structural foundations of the northern Carnarvon Basin.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R.,(eds).The North West Shelf, Australia: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 349-372.

Tindale, K., Newell, N., Keall, J., Smith, N., 1998.Structural evolution and charge history of the Exmouth Sub-basin, northern Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia.In: Purcell, P.G., Purcell, R.R.,(eds).The Sedimentary Basins of Western Australia 2: Proceedings of Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia Symposium.Perth: WA, 447-472.

Zhang Shanwen, Wang Yingmin, Li Qun, 2003.Searching subtle traps using the theory of slope break.Petroleum Exploration and Development, 30(3): 5-7 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhu Xiaomin, Yang Junsheng, Zhang Xilin, 2004.Application of lithofacies palaeogeography in petroleum exploration.Journal of Palaeogeography, 6(1): 101-109 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年1期

Journal of Palaeogeography2013年1期

- Journal of Palaeogeography的其它文章

- Facies-succession and architecture of the thirdorder sequences and their stratigraphic framework of the Devonian in Yunnan-Guizhou-Guangxi area,South China

- Classifications, sedimentary features and facies associations of tidal f lats

- Review of research in internal-wave and internal-tide deposits of China

- The response of deltaic systems to climatic and hydrological changes in Daihai Lake rift basin,Inner Mongolia, northern China

- The palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres

- Palaeobiogeographical constraints on the distribution of foraminifers and rugose corals in the Carboniferous Tindouf Basin, South Morocco