Learning Mandarin in Later Life: Can Old Dogs Learn New Tricks?①

.

University of Minnesota, USABeijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, China

This case study reports on a native English speaker’s learning of Mandarin as a 13th language starting at the age of 67. The learner, after completing a 150-hour, 3-DVD course called Fluenz Mandarin, had 70 online sessions with a Chinese-language instructor from a Beijing-based University. The learning content focused mainly on pinyin, a Romanization system for the pronunciation of Standard Mandarin. The sessions contained real-life communication in Chinese based on Chinese sentences produced beforehand by the learner consistent with his life experiences and professional interests as an applied linguist. After the sessions, the instructor developed the sentences into formulated language and kept a detailed log with the learner’s feedback as well. Meanwhile, the learner created electronic flashcards for words and phrases to review. The paper considers the impact of advanced age, hyperpolyglot status, and the use of a sophisticated language strategy repertoire on Mandarin learning. The paper reports on the learner’s results as viewed from the vantage point of the learner and from that of his instructor as well, paying particular attention to vocabulary (e.g., the use of measure words and the overabundance of homonyms and near homonyms), grammar (e.g., word order), and pronunciation (e.g., the perception and production of the four tones).

Keywords: long-term Memory, hyperpolyglot, strategy repertoire, tones, pinyin mnemonics

Correspondence should be addressed to Professor Andrew D. Cohen, 1555 Lakeside Drive, #182, Oakland, CA 94612, USA. Email: adcohen@umn.edu

INTRODUCTION

Global language learning is gaining momentum in dramatic proportions. Learners are taking on ever more challenging languages for them, with some differences in learning according to whether it is a second language or a foreign language (ELT Global Blog/OUP, 2011). For example, there has been a striking rise in Chinese immersion programs for U.S. pupils. So instead of opting for Spanish, a relatively easy language for English speakers and one where contact with native speakers is readily available, students are choosing to study a difficult language for English speakers and one where contact with natives may be more limited. Whereas young school children may be successful at acquiring Chinese under immersion conditions (i.e., from the age of five, with full-time exposure to the language), what about elderly adults? The literature of case studies tends to focus on college-age learners (e.g., Caasi, 2005). But what about those over 65 and therefore well beyond that age range?

In reality, there is a paucity of research literature on senior learners of a second language (L2). The literature tends to compare children with all adults lumped together (e.g., Cook, 1995). The impact of age was presented many years ago by Schleppegrell (1987). She noted that while elderly learners would need emphasis on listening before speaking given possible hearing loss and problems with vision, there is no decline in the ability to learn as people get older. In fact, she maintained that their self-directedness, life experiences, independence as learners, and motivation to learn equip them with advantages in language learning. In addition, there is the possibility that elderly learners by virtue of living many more years could have had more opportunities to learn languages. Hale (2005) added that “(a)lthough middle-aged adults tend to experience some short-term memory loss, some decline in the ability to retrieve items from the long term memory, and a slowing of processing speed, these losses are gradual and are not severe enough to rule out second language learning.” No matter how gradual, the bottom line is that L2 learning processes and outcomes among elderly adults have been shown to differ from those of younger learners, taking into account individual differences among seniors, particularly with regard to working memory (see Mackey & Sachs, 2012).

In his book onhyperpolyglots, Erard (2011) described the exploits of individuals who had studied at least a dozen languages or more. These learners would have appeared to be adding languages to their repertoire the way some people add a new pair of shoes. Is this really the case? Doesn’t the learning of language involve hard work, even for hyperpolyglots? And what role, then, would this enhanced ability to learn languages have when encountering a truly challenging language for the given learner, such as Chinese for a native English speaker? While the knowledge of multiple languages has to play a positive role in the learning process, it still stands to reason that the features of the specific language itself will determine to some extent the level of success of the particular learner with the given language.

There is also by now an extensive literature on the role of language learner strategies in the learning process and on the contribution that strategizing can make (Oxford, 2011; Cohen, 2011). There is, in fact, a robust literature indicating that strategy instruction does improve the performance of language learners (Plonsky, 2011).

This paper attempts to address three research questions:

(1) What is the impact of advanced age on learning Mandarin?

(2) How does the previous learning of many other languages influence the learning of Mandarin?

(3) What role does the learner’s language strategy repertoire play in the learning and performance in a difficult language like Mandarin?

METHOD

TheSubject

The study was a case study of a single learner, co-author Cohen, but drew for comparative purposes on the performance of middle-school and college students as well. The learner and co-author of this paper began his study of Mandarin at the age of 67, making him an elderly learner. It was the 13th language that he had learned, which made him a hyperpolyglot. In addition he was an expert on language learner strategies and made use of a robust repertoire of strategies when he learned and used the various languages. While it is true that being over 65 years of age is only one variable here, it is an important one in that language learning results for considerably older learners are not readily available in the literature.

Although technically just a case study of one learner, this study benefited from the fact that the learner’s teacher and co-author of this article (see below) was at the beginning of the study also teaching middle-school children and college students Mandarin on a Fulbright in California. This provided the opportunity for a non-rigorous comparison between this learner and the students. The middle schoolers were 72 6th-8th graders. For the 6th and 7th graders it was a twice-weekly 60-minute course called “Chinese Language and Culture,” and for the 8th graders a once-a-week course with the same title, at the Broadoaks Children’s School, a demonstration school attached to Whittier College in Whittier, CA. The college students were 13 Whittier College students taking first-year Chinese. It needs to be noted at the outset that the comparison of this senior learner with middle-school and college students is only meant to be suggestive, given the number of variables that could not be controlled in making the comparison. One major difference was that Cohen was not learning Chinese characters, whereas the middle schoolers and college students were.

TheTreatment

The learner completed a 150-hour, 3-DVD course calledFluenzMandarinand a series of approximately 70 sessions with his teacher, co-author Li Ping, an EFL and Chinese-language instructor from the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications initially while on a Fulbright in the U.S. and then when back at her university in Beijing, via Skype, FaceTime, and iPhone communication. Most of the sessions were tandem sessions, so they partly entailed a Chinese lesson and partly a session in English about topics in applied linguistic research.

The Chinese instruction initially involved textbook material fromEncounters(Yale University and China International Publishing Group, 2012), but ultimately focused on material generated by the learner in keeping with his life experiences and professional interests as an applied linguist. The learner used only thepinyinsound system, consistent with the approach inFluenzMandarin, so he did not deal with Chinese characters. Pinyin provided him the tones for the vocabulary. He created electronic flashcards for words and phrases using Flash My Brain (Mode of Expression, 2007). The instructor kept a teaching log as an Excel file with details of every session and with feedback from the learner.

The learner had another tandem partner, Yue Yang, a Chinese woman from Beijing based in the learner’s home city at the time, Minneapolis. At the time of the study they had met about 30 times in that city and then had added perhaps 10 Skype sessions as well.

TheSourcesofDataandtheAnalysis

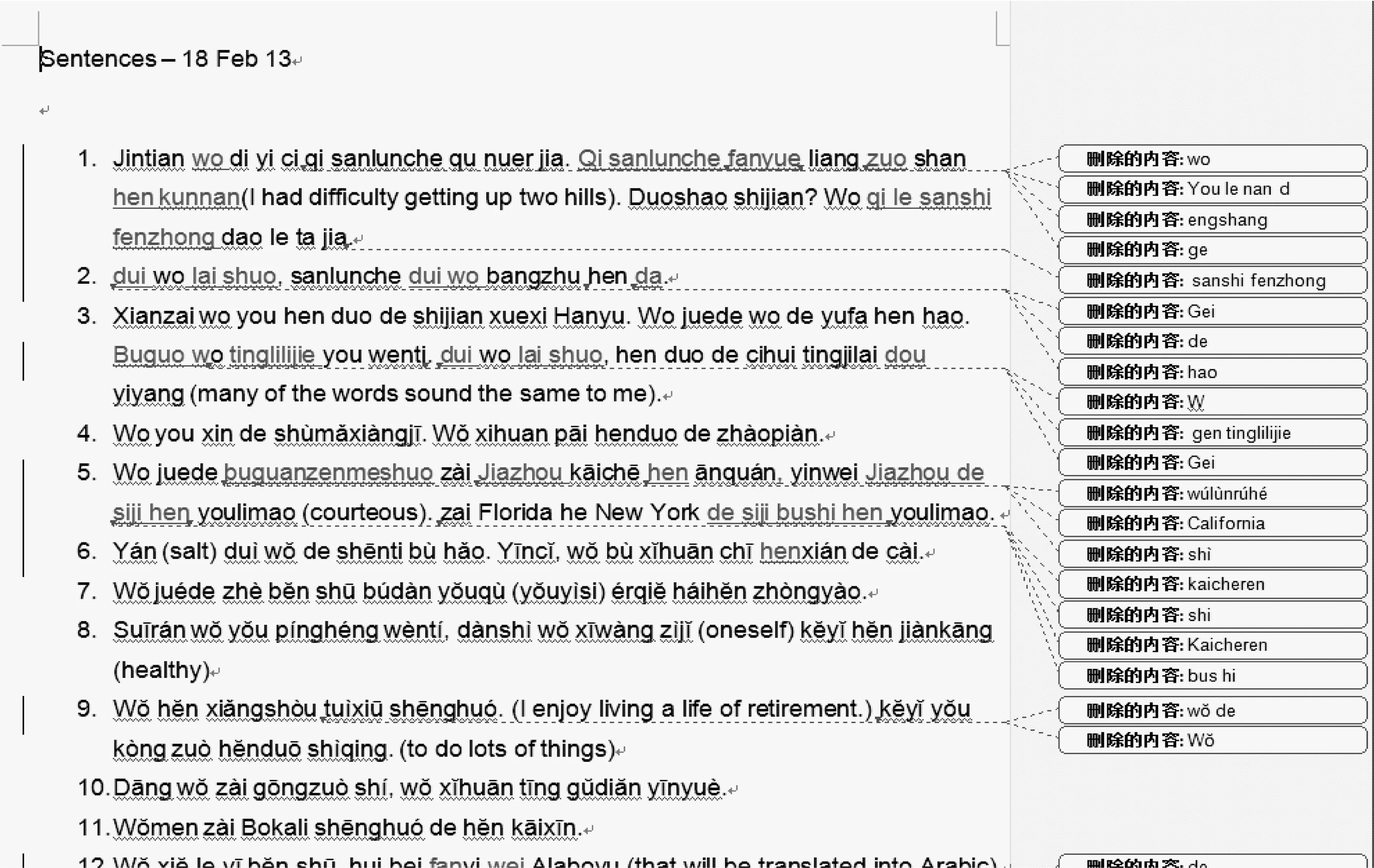

The learner provided his teacher, co-author Li Ping, continual data from the beginning of their mutual study, both in the form of oral language and written sentences which he prepared prior to most of their sessions. She then corrected these (see Figure 1) and provided a recap of the lesson in written (see Figure 2) and audio form. He studied the corrected sentences, and then recycled material from them into subsequent sentences. When he did not understand something that she had said, she would write it down via the chat mode in Skype. There were two forms of analysis of these task performance data-evaluative assessment by the teacher and self-assessment by the leaner.

The data on the learner’s strategies for learning and using Chinese were collected through verbal report, in the form of retrospective self-observation. The learner would do language tasks and then describe either live or by email the strategies that he had used to perform the given tasks. In other words, for the most part the data consisted of verbal report just after the task was completed, where the learner provided his own analysis as to what he did and why. In some cases, Li Ping would enter this information into her Excel file where she was tracking the results from each interactive session.

Figure 1 Sentence Correction

A source of data for comparative purposes was interviews with four students who had studied Chinese at Whittier College in Whittier, CA the previous year. The students had been taught four times a week by their main teacher (originally from Taiwan) and once a week by the TA, Li Ping. The main teacher used mainly a grammar-translation method while the TA preferred and adopted communicative language teaching methods. The students learned traditional Chinese characters from a textbook compiled by the teacher. Stroke orders and translation made up a large portion of their final exam. After the completion of the course, the four former students were interviewed through Skype and Facebook and were asked about the problems that they had encountered in learning Chinese. The performance results for the 6th-8th graders studying basic Chinese vocabulary and phrases provided another source of data. Thus, there were both college-level and middle-school-level data in order to make some comparisons with the learner’s performance, however qualitative and impressionistic the comparisons were.

FINDINGS

TheImpactofAgeonLearningMandarin

TheLearner’sView

The learner felt that his age had a negative impact on his efforts to learn Mandarin. His main concern was his deficiency in long-term memory—his inability to remember material both initially and over time. Aside from his inability to perceive and produce correctly the four tones that accompanied the vocabulary to memorize, he also found it extremely challenging to use the measure words correctly, to correctly distinguish homonyms and near homonyms, and to both perceive and produce consonants such as /zh/, /ch/, /j/, and /q/.

As a consolation to the learner, Li Ping found that the four interviewees from among the students that she had taught at Whittier College all reported tones to be a challenge in learning Chinese. With regard to strategies for learning tones, they mentioned “repeating the words slowly—accentuating the tones,” “practicing the words with their correct tones frequently,” and “l(fā)inking the sounds of the tones to specific characters”—a strategy that the learner could not use since he was not learning the characters at this time. A strategy that the learner developed was to group the mostly two-syllable words according to the tone configuration, of which there were over 20 possible combinations (see Figure 3). He found that this strategy afforded him at least some way to deal with the fact that given words had unpredictable tone patterns.

In fact, the learner reported that his most conspicuous problem involved efforts to learn and then remember the four tones associated with the vocabulary. He would learn the tones for the given words in order to perform them in speaking and to use them in writing, but subsequently he found himself forgetting them again, even in words that he had used many times. TheFluenzMandarincourse, for example, required that he get the tones correct on all pinyin that he used in written exercises in the lessons. Inputting this information took a good deal of the lesson time. He found that when writing sentences in pinyin for his tandem partners, he preferred to write without indicating the tones at all, except on certain new words, primarily so as to save an enormous amount of time.

Another challenge that the learner mentioned was that of keeping alive in long-term memory words and phrases that he was using on a limited basis or not at all. A case in point was his fluctuating control over the color words. He hardly ever talked about or wrote about the colors of things with his two tandem partners. So, the learner most definitely viewed the challenge of retrieving language material as a major one, especially material with which he had little or no contact in the interim. The good news was that when he relearned the color words, there was asavingseffect, namely, the fact that he had learned the words once made the relearning easier (Russell, 2005). So, it was relatively easy for him to relearn the colors that he had already learned:lán,lǜ,huáng,chéng,hóng,bái,hēi,huī.②But adding on a new color (méiguī ‘rose’) was more difficult.

TheTeacher’sView

Compared to the middle schoolers and college students, the learner seemed to be more motivated and resourceful in learning, and performed better in terms of tones, vocabulary accumulation, and especially complexity of grammar and syntax. Hard work and perseverance helped him pick up the language and make progress faster than the other two groups, despite his advanced age. The learner was highly extroverted and independent, preferring one-on-one teaching and learning to larger group situations because he could go at his own fast pace.

Another difference between the Whittier College students and the learner was that he learned the language by extensive language production, both in oral and written forms, while the Whittier students learned the language more from receptive skills, like listening and reading.

There were two tests completed during the first sessions, in which the learner performed very well—beyond the teacher’s expectations. Here are the observations that the teacher made in the two oral tests:

? Oral test 1: “The student outperformed the quiz questions. He answered with more material than expected. Extra points would have been given if it had been a quiz” (2012/4/30).

? Oral test 2: “More fluent than on the first test and almost 100% correct” (2012/5/11).

TheEffectofPreviousLearningofNumerousOther

Languages

TheLearner’sView

The fact that he had studied 12 languages before the onset of Chinese made him more acutely aware of how he wanted to study Chinese—namely following to some extent his own curriculum rather than that of an existing course. The Fluenz course suited his purposes because it emphasized learning a small language set well rather than covering a lot of language material in passing.

The learner reported drawing on other languages that he had learned, such as Japanese, Hebrew, and his Romance languages (Spanish, French, and Portuguese) when learning Chinese. For example, when using the strategy of checking what could be learned from errors in word order, he found that his knowing other languages made it interesting for him to see how Chinese communicated concepts syntactically. He found that usually the word order patterns of Chinese were similar to those of one or another language that he had already studied. So it stimulated his curiosity to see when he got feedback on his written sentences how well he predicted acceptable word order.

TheTeacher’sView

The subject’s talents at languages exhibited themselves in numerous instances tracked in the teaching log. Here are some examples involving positive transfer and cross-cultural awareness:

a. Positive transfer

The teacher recorded that in the beginning sessions the learner comprehended fast:

? “There is no need to repeat some explanations, like when I repeated the use of the measure word wèi” (2012/4/12).

The student used positive language transfer to his advantage: he found a similar pattern in Hebrew to that ofba(吧), the lack of capitalization in pinyin, and a parallel to the use oftāmen(他們) ‘they’ (2012/4/20). In other words, he instantly got to know the rules for forming the plural form of some pronouns like “they.” It was a “noun+men” pattern likewǒmen(我們) ‘we,’nǐmen‘you plural,’ andtāmen‘they.’

? The learner noted positive language transfer from Portuguese (e.g. The Chinese wordkěyǐ meaning ‘can’ functions like the Portuguese word ‘pode’) (2012/4/27).

? When he found that some words in English did not have an equivalent in Chinese (like “artistic,” “athletic,” and “militaristic”), he noted a similar phenomenon in other languages—e.g., no word for “integrity” in Hebrew until recently (when the Hebrew Academy decided onyoshra), nor for “insight” in Portuguese (2012/5/10).

b. Cross-culture awareness

The learner was quick to spot the difference in cultures conveyed through the language. For example, in Chinese when people greet each other in a casual manner, they do not usually say “How are you doing?” but instead say something related to a specific situation, like “Where are you going?” or “So you are going shopping.” He compared this to Hebrew culture, in which in response tobokertov“good morning,” people might respond withboker“morning light.” Or when someone indicated in Hebrew that they had bought something new, they may be greeted withtitxadesh“may you be renewed by the purchase.”

TheRoleoftheLearner’sLanguageStrategy

Repertoire

TheLearner’sView

The learner reported drawing repeatedly from his robust repertoire of language learner and language use strategies in order to cope with the learning process. For example, it became clear to him that much of the often monosyllabic language directed at him orally using FaceTime was difficult to understand. So he made sure that if he did not understand the oral language, his tandem partners would write down words and phrases using the chat mode in Skype. He usually would have an easier time of interpreting the written text. If not, he asked for translation. In fact, judicious use of translation was a strategy that he relied on heavily, even when there was an opportunity to figure out meanings from context. He eventually started using the Google Translate app on his iPhone, although he quickly learned that perhaps half of every translation was specious in one way or another. Consequently, an important strategy for him was to verify every translation Google provided with his tandem partners. They invariably substituted other more appropriate vocabulary and often changed the word order as well.

Since his learning style preferences included being analytic and being a sharpener rather than a leveler (i.e., keen to get distinctions clear at the onset of the learning process), his strategy when first learning forms was to keep asking until he got resolution regarding material that was ambiguous to him. So, for example, when his co-author tandem partner told him that bothméiguānxiandméishìrwere appropriate responses for an apology (Hěnbàoqiànràngnǐjiǔděngle“Sorry for keeping you waiting”), he wanted to know the actual semantic coverage pragmatically of the two responses. The reply from his tandem partner was that while the former (méiguānxi) was more specific to apologies and that it meant “It doesn’t matter; it doesn’t have much consequence,” the latter (méishìr) had a more general meaning (“No big deal; don’t mention it”), which could be used even as a response to one’s expression of thanks.

Another of the learner’s strategies was to keep flash cards of vocabulary to make review of the material easier. His receptive and productive ability with the vocabulary that he studied was relatively good. He chose to write practice sentences each week as a way to recycle the new vocabulary. The middle schoolers that Li Ping taught in Whittier were not good at retaining the words that they were exposed to. They tended to forget the phrases learned even just one or two weeks prior. Only the few students who actually had had Chinese lessons or training before her course could remember all or most of them.

The Whittier College students had difficulty memorizing characters and tones. Their pronunciation (especially tones) was less accurate than the learner’s. With regard to the four learners that the teacher interviewed for this paper, they reported spending too much time on stroke orders of characters (an essential part of their final exam). Besides, they were learning traditional Chinese characters which had even more strokes than in the currently used language in China.

Still another of the leaner’s strategies was to find a good online dictionary (MDBGChinese-EnglishDictionary; http:∥www.mdbg.net/chindict/chindict.php), where he could enter a word in English or Chinese and get the equivalent in the other language. As with the Google Translate app, he would check the individual word choices with a tandem partner to make sure that their denotation or connotation was appropriate for the context, and that the word was not too formal or informal.

The learner noted that especially learning on his own, it was crucial to strategize so as to keep his motivation going. One motivational strategy was to make sure that the vocabulary that he made electronic flash cards for were, for the most part, words that he wanted to know—rather than the inane vocabulary that he was force fed in lessons in his previous learning of Japanese (e.g., vocabulary for buying a tie in a department store: “gaudy,” “subdued,” “polka dot,” “plaid,” and “striped”).

An additional strategy was to pay attention to grammar and to construct sentences with complex grammatical constructions rather than avoiding them. The reason for this strategy was that he had done his MA in general linguistics and was basically curious about how the grammar worked. The learner often associated new grammar structures with their counterpart in another language. For example, he drew on his French grammar injenejamais... to understand the adverbialháibù in thewǒháibù structure. This strategy separated him dramatically from the middle schoolers in Whittier who Li Ping taught. They were unable to use syntax to link words together. They just remembered short phrases likehǎojiǔbújiàn“l(fā)ong time no see.” The longest sentence that they learned washěngāoxìngrènshinǐ “nice to meet you.” The 7th graders were required to write a play script, but used as their strategy to make use of Google Translate and the teacher’s proofreading in order to produce it.

TheTeacher’sView

The learner clearly utilized a rich strategy repertoire. Here are some examples that were noted:

a. Putting the words in context to remember and to practice them. Almost every time he learned a new word, the learner would make up a sentence immediately using that word.

b. Sorting and grouping vocabulary (alphabetically and by part of speech). The learner showed the teacher his word lists which were grouped alphabetically by part of speech (see Figure 4).

c. Mnemonics—making associations to known words in other languages, mostly using the mnemonic keyword approach involving the making up of phrases in English or Chinese roughly equivalent to the sounds of the target words. For example, he rememberedguǎizhàng“walking sticks” by remembering “this guy John who had walking sticks.” As another example of mnemonics, he rememberedzhòngyào“important” by remembering the sentence, “Chinese medicine is important (Zhōngyàozhòngyào),” sincezhōngyàomeans “Chinese medicine.”

Figure4 Grouping of Vocabulary (alphabetically, part of speech)

DISCUSSION

SummaryofFindingsandCommentary

This case study reported on a native English speaker’s learning of Mandarin as a 13th language starting at 67. It considered the impact of advanced age, hyperpolyglot status, and a sophisticated language strategy repertoire. The findings, however impressionistic and non-rigorous in quantitative terms, still showed that at least one old dog can learn some new tricks, though in the learner’s estimation he did not necessarily perform them so well. His advanced age did have a negative impact, primarily because his memory did not work as well as it had when he was busily adding new languages in his twenties and thirties.

From the teacher’s viewpoint, the learner had developed impressive Chinese skills. She considered him a very successful learner, since Mandarin is proved to be more difficult to pick up than many other languages that are more similar to English. According to the Foreign Service Institute, Chinese is among Category Ⅴ—“an exceptionally difficult language for English speakers.” An English L1 learner is expected to spend over 88 weeks (2,200 hours) to reach the level of “Speaking 3: General Professional Proficiency in Speaking (S3)” and “Reading 3: General Professional Proficiency in Reading (R3)” according to the Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) Scale (http:∥www.effectivelanguagelearning.com/language-guide/language-difficulty). Given that the learner spent only some hundreds of hours in the tandem sessions and review, the teacher felt that he had performed exceptionally well in that he touched upon S3 and R3 to some degree in his limited vocabulary set. His success was attributed to the following in the teacher’s opinion:

? his goal to learn the language for communicative purposes despite his advanced age,

? his strong will to add Mandarin to his large collection of languages (despite a brain concussion after a bicycle accident),

? perseverance and hard work,

? a full array of language learning strategies, and

? rich language and cultural experiences in his lifetime.

Limitations

We must bear in mind that this study reports on just one subject, involved little or no formal testing of language ability, focused just on curriculum of interest to the learner, and involved a subject who did not study Chinese characters at all. His counterparts at Whittier College were, in fact, having to learn Chinese characters along with the other material, which took time away from more communicative activities.

In addition, the subject learned Chinese for purposes that might be different from many (if not most) other learners. His objectives for learning Mandarin, according to a needs analysis which the teacher conducted before engaging in the 70 sessions, were not only to speak some Chinese in real situations, but also to research his efforts to deal with the different aspects of a truly challenging language for him (e.g., the sound system, the grammar, the vocabulary, and the pragmatics). His advanced expertise in using language learner strategies and his status as a hyperpolyglot would also set him apart from the average learner.

SuggestionsforFurtherResearch

It would be beneficial to compare the results of this learner to those of other language learners at a similar age with similar language skills. The main focus would be on language learning among seniors over the age of 65. Of particular interest would be to identify senior learners who have achieved good skill with the Chinese tone system and to determine the strategies that they have used in this achievement. Some key variables here could be that of the context, the purpose for learning Mandarin, and their previous language learning experiences. For example, in the case of this learner, his contact with native speakers was limited to his two tandem partners with whom he met perhaps once a week. For comparison purposes, it would be of value to collect data on seniors who are submersed in a Chinese-speaking environment.

PedagogicalImplications

A primary intention for describing the experiences of seniors learning Chinese would be to pass on these insights to other learners. While the average senior learners are not hyperpolyglots, they nonetheless may have developed a repertoire of strategies that could be of benefit to other learners.

This study could also provide insights for teachers regarding curriculum development, the role of the teacher, and teaching methods in general. The teacher in this study, Li Ping, believed in a student-centered curriculum and considered the teacher’s role as mainly that of facilitator. She used a communicative language teaching approach and generated real-life dialog material in Chinese primarily through reformulating the students’ oral and written production. This approach provided the learner with comprehensible input—for the most part, using vocabulary that he knew and adding just a few new words (e.g., keeping the input a little beyond his interlanguage level or i+1).

She would introduce occasional grammatical rules and exercises based entirely on the grammatical errors (e.g., mistakes in word order) that occurred in his communication. An effort was made to limit the introduction of grammar rules to what was immediately relevant to the situation at hand. Consequently, the teacher tolerated some interlanguage forms, correcting serious mistakes before they would fossilize (e.g., notduōdebut ratherhěnduōde“a lot of”). This student-centered and communicative language teaching approach was intended to keep the learner’s motivation high, despite the difficulty of the language.

CONCLUSION

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, global language learning is gaining momentum. Consequently English-speaking learners are shifting from the study of a relatively easy language for them, Spanish, to a far more difficult one in the study of Chinese. So, the difficulties posed by the language itself, problems associated with only limited exposure to speakers of the language, and the challenges facing older learners of Mandarin make it a rich context for research. Hopefully in the years to come we will achieve a better sense of what it takes to succeed at such an endeavor.

NOTES

1 The participation of the second author in this project was made possible through a grant from the Ministry of Education in China [“Research on Multidimensional Assessment for a Web-Based English Audio-Video Speaking Course” (12YJA740052)] and a grant from Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press [“Individualized Instruction in Large Classes of College English in CALL Environments” (S2013025)].

2 Mandarin Chinese has four pitched tones and a “toneless” tone:

ToneMarkDescription1stdāHigh and level2nddáStarts medium in tone, then rises to the top3rddǎStarts low, dips to the bottom, then rises toward the top4thdàStarts at the top, then falls sharply and strong to the bottomNeutraldaFlat, with no emphasis

REFERENCES

Bardovi-Harlig, K. & Stringer, D. (2010). Variables in second language attrition: Advancing the state of the art.StudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition, 32, 1-45.

Caasi, H. (2005). The Thomson method of study for second language acquisition: A diary study. M.A. Capstone Paper. Hamline University, St. Paul, MN. Retrieved September 20, 2013, from http:∥www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&cad=rja&ved=0CC4QFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.hamline.edu%2FWorkArea%2Flinkit.aspx%3FItemID%3D4294991739&ei=ulU8Up_iD8jBrQG6u4GYAQ&usg=AFQjCNGwKvQ7mCN3 AFLl7R6nxNNKZEkmcw&bvm=bv.52434380,d.aWM.

Cohen, A. D. (2011).Strategiesinlearningandusingasecondlanguage(2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Cook, V. (1995). Multi-competence and effects of age. In D. Singleton & Z. Lengyel (Eds.),Theagefactorinsecondlanguageacquisition(pp. 51-66). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Retrieved September 20, 2013, from http:∥homepage.ntlworld.com/vivian.c/Writings/Papers/MCAge95.htm.

Erard, M. (2012).Babelnomore:Thesearchfortheworld’smostextraordinarylanguagelearners. New York: Free Press.

Hale, C. (2005). Helping the older language learner succeed.ICCTCoachnotes. Wheaton, IL: Wheaton College. Retrieved September 20, 2013, from http:∥www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/ICCT/pdf/CN_older.pdf.

Language Difficulty Ranking. (n.d.). Retrieved September 20, 2013, from http:∥www.effectivelanguagelearning.com/language-guide/language-difficulty.

Mackey, A. & Sachs, R. (2012). Older learners in SLA research: A first look at working memory, feedback, and L2 development.LanguageLearning, 62, 704-740.

Oxford, R. (2011).Teachingandresearching:Languagelearningstrategies. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Plonsky, L. (2011). The effectiveness of second language strategy instruction: A meta-analysis.LanguageLearning, 61, 993-1039.

Russell, R. A. (2005).AcquisitionandattritionofconditionalsinJapaneseasasecondlanguage. Paper presented at the AILA World Congress, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, July 26, 2005.

Schleppegrell, M. (1987). The older language learner. ERIC Digest. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics, ED 287313. Retrieved September 20, 2013, from http:∥www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CC4QFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Ffiles.eric.ed.gov%2Ffulltext%2FED287313.pdf&ei=nlc8UpTCB86pqQHAr4D4Cg&usg=AFQjCNE37qyoKh O4yz25Cd0lTXrQLmgykg&bvm=bv.52434380,d.aWM&cad=rja.

- 當(dāng)代外語(yǔ)研究的其它文章

- Thinking Metacognitively about Metacognition in Second and Foreign Language Learning, Teaching, and Research:Toward a Dynamic Metacognitive Systems Perspective

- Metacognition Theory and Research in Second Language Listening and Reading: A Comparative Critical Review

- Codeswitching in East Asian University EFL Classrooms:Reflecting Teachers’ Voices①

- Making a Commitment to Strategic-Reader Training

- Modality, Vocabulary Size and Question Type asMediators of Listening Comprehension Skill

- Toward a Theoretical Framework for Researching Second Language Production