Combining targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of metastatic melanoma

Teresa Kim*, Rodabe N. Amaria*, Christine Spencer, Alexandre Reuben, Zachary A. Cooper,, Jennifer A. Wargo,

1Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA;

2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA;

3Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology,

4Department of Genomic Medicine,

5Department of Surgical Oncology, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Combining targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of metastatic melanoma

Teresa Kim1,2*, Rodabe N. Amaria3*, Christine Spencer4, Alexandre Reuben5, Zachary A. Cooper4,5, Jennifer A. Wargo4,5

1Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA;

2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA;

3Department of Melanoma Medical Oncology,

4Department of Genomic Medicine,

5Department of Surgical Oncology, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer and has an incidence that is rising faster than any other solid tumor. Metastatic melanoma treatment has considerably progressed in the past fi ve years with the introduction of targeted therapy (BF and MEK inhibitors) and immune checkpoint blockade (anti-CTLA4, anti-PD-1, and anti-PD-L1). However, each treatment modality has limitations. Treatment with targeted therapy has been associated with a high response rate, but with short-term responses. Conversely, treatment with immune checkpoint blockade has a lower response rate, but with longterm responses. Targeted therapy a ff ects antitumor immunity, and synergy may exist when targeted therapy is combined with immunotherapy.is article presents a brief review of the rationale and evidence for the potential synergy between targeted therapy and immune checkpoint blockade. Challenges and directions for future studies are also proposed.

Melanoma; checkpoint blockade; BF inhibition; immunotherapy

Introduction

Epidemiology of melanoma

Skin cancer is among the most common cancer types globally1. Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer2. Its burden on public health continues to rise, with its incidence increasing faster than any other cancer in recent years1,2. Early stage melanoma is treatable with surgery, but the late stage of this disease is oen fatal3. This review discusses the treatment options for patients with advanced melanoma and the rationale for combining targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat these patients.

Treatments for advanced melanoma

Chemotherapy

Treatment options for advanced melanoma were limited in the past decade, and prognosis was universally poor. Cytotoxic chemotherapy was the main treatment strategy but was marginally e ff ective only in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic disease. Dacarbazine [5(3,3-dimethyl-1-triazeno)-imidazole-4-carboxamide] was the primary agent used, and this drug remains the only FDA-approved chemotherapy for metastatic melanoma. However, therapy is characterized with low overall response rates (approximately 10%-15%), and the drug o ff ers no survival bene fi t4,5.

In addition to dacarbazine treatment, biochemotherapy regimens and combined chem otherapeutic agents (e.g., dacarbazine or temozolomide with vinblastine and cisplatin) with cytokine-based therapy [e.g., interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-alpha] had been administered to improve response rates by inducing immunogenic cell death. Two large metaanalyses that evaluated the standard chemotherapy versusbiochemotherapy in 18 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving more than 2,600 patients with metastatic melanoma show that biochemotherapy regimens can improve overall response rates, but with greater systemic toxicity and without a statistically signi fi cant survival bene fi t6,7.

Immunotherapy

Another modality in melanoma treatment involves the use of immunotherapy. The first immune-based therapy with demonstrated clinical benefit in melanoma patients was IL-2, an immune stimulating cytokine integral to T cell activation and proliferation. Atkins et al.8examined 270 patients with metastatic melanoma treated with high dose IL-2, and 16% of patients who achieved complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) showed long-term responses, with a median progression free survival (PFS) of 13.1 months. Longer follow-up time of the patients demonstrated an approximately 6% CR rate9. A follow-up phase III RCT by Schwartzentruber et al.10demonstrated a small but statistically significant improvement in objective response rate (ORR) associated with the addition of the gp100 peptide vaccine to high dose IL-2, although, again, in only a small percentage of patients (16% vs. 6%) treated with vaccine plus IL-2 versus IL-2 alone.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have also been successfully used to treat melanoma. This therapy is based on the fact that T lymphocytes are critical to antitumor immunity, and activation by an antigen-specific T cell receptor in the context of costimulatory activation is required. However, a naturally occurring feedback mechanism that prevents excess immune activation through the expression of negative costimulatory molecules exists11. These negative costimulatory molecules, also known as “checkpoints”, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTL A-4), programmed death 1 (PD-1), T cell immunoglobulin 3, and lymphocyte-activation gene 3, act as“brakes” on T cell activation and serve as negative feedback mechanism11. Interestingly, tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes (TIL) in many tumor types express high levels of negative costimulatory markers, suggesting a tumor-derived mechanism of suppressing antitumor immunity and providing rationale for T cell checkpoint blockade12.

In a milestone phase III RCT of 676 patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma treated with either anti-CTL A-4 antibody ipilimumab, gp100 peptide vaccine, or combined ipilimumab plus vaccine, patients treated with either ipilimumab arm had improved overall survival (OS) compared with those treated with vaccine alone (10.0 vs. 6.4 months)13. Ipilimumab alone achieved the best overall response rate in 10.9% of patients, and 60% of these patients benefitted from long-term responses lasting greater than 2 years. However, ipilimumab therapy was also associated with higher toxicity rate, with 10%-15% of patients suffering from grade 3 or 4 immune-related adverse events (AEs) such as diarrhea or colitis, dermatitis, and pruritis13. Similar results were reported in a second RCT, which compared ipilimumab plus dacarbazine versus dacarbazine alone in 502 patients with advanced melanoma, but this study utilized a higher dose (10 mg/kg) of ipilimumab14. Response rates were 15% in the ipilimumab with dacarbazine-treated group but with higher toxicities. Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 56% of patients14.

Topalian et al.15recently reported the results of the phase I trial of 296 patients with either advanced melanoma or other solid tumors, which included non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and colorectal cancer, in which the checkpoint blocking antibody anti-PD-1 (BMS-936558, nivolumab) achieved a 28% response rate in melanoma patients, with long-term responses longer than 1 year in 50% of responding patients. Anti-PD-1 therapy was associated with a lower rate of grade 3 or 4 AEs compared with ipilimumab. Interestingly, Topalian et al.15suggested a possible association between tumor expression of the PD-1 ligand PD-L1 and response to anti-PD-1 therapy. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this finding. In a pooled analysis of 411 melanoma patients treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody MK-3475 (pembro lizumab, M erck Sharp e & D o hme) with over 6 months of follow-up data, the ORR was 40% in ipilimumab na?ve patients and 28% in ipilimumab refractory patients16. Median PFS was 24 weeks, but median OS had not been reached at the time of analysis. Pembrolizumab was well-tolerated with 12% of patients experiencing a grade 3 or 4 AE aributed to the drug, but only 4% of patients discontinued treatment because of AE16.is agent was FDA-approved for metastatic melanoma in early September 2014.e antibody blockade of PD-L1 in the phase I trial of 207 patients using BMS-936559, including 55 with advanced melanoma, achieved an objective response in 17% of melanoma patients, with more than half of patients achieving long-term responses lasting longer than 1 year and a comparable rate of grade 3 or 4 AEs17. Although this agent is currently not being tested, two anti-PD-L1 antibodies, namely, MPDL3280A (Genentech) and MEDI4736 (MedImmune), are being tested in solid tumors under early phase clinical trials.

In addition to their use for monotherapy, different immune checkpoint inhibitors are now being combined in clinical trials, which showed impressive response rates. In the phase I trial of 86 patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma treated with either concurrent or sequential ipilimumab and nivolumab, concurrent CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade achieved a higher ORR of 40%, with 53% of patients achieving CR orPR at the maximum doses tested, whereas 31% of responders demonstrated tumor regression of 80% or more even with bulky disease18. In 53% of patients, grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred at a higher frequency in combined therapy than in monotherapy, the majority of which were reversible with appropriate supportive management18. In a recent update, the 1-year OS rate for patients treated with combined immune checkpoint inhibitors was 85%, and their 2-year survival rate was 79%19.

Additional strategies targeting checkpoint inhibitors and other immunomodulatory molecules are currently being studied. However, a thorough discussion of these strategies (as well as other strategies such as treatment with tumor-in fi ltrating lymphocytes) is beyond the scope of this review.

Targeted therapy

Concurrent advances in targeted molecular therapy have also improved the treatment and prognosis of a subset of advanced melanoma patients. Approximately 50% of cutaneous melanomas harbor an activating mutation in the BRAF oncogene, leading to constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway involved in cellular proliferation and survival20. Preclinical studies of vemurafenib (PLX4032), a potent oral small molecule inhibitor of mutated BR AF, have culminated in a phase III RCT of vemurafenib versus dacarbazine in 675 patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma21. The vemurafenib arm resulted in improved OS (84% vs. 64% at 6 months) and higher response rate (48% vs. 5%) than standard chemotherapy, representing the only treatment other than anti-CTLA-4 to improve survival in metastatic melanoma21. Similar results were demonstrated in a phase III RCT, in which another potent BFV600Einhibitor, dabrafenib, was compared with dacarbazine22. Despite improvements in response rate and survival, BRAF inhibition achieved only a median PFS of 6 months, implying rapid development of tumor resistance21,22. Further investigation of resistance mechanisms has suggested that BRAF-mutated melanoma cells can maintain MAPK signaling throughF-independent activation of MEK, a kinase downstream ofF in the MAPK cascade23. Translating these fi ndings to clinical studies, Flaherty et al.24demonstrated that combined BRAF and MEK inhibition (dabrafenib plus trametinib vs. dabrafenib alone)achieved a higher overall response rate of 76% versus 54%, as well as a longer median PFS of 9.4 vs. 5.8 months. Similar to immunotherapy, combination molecular therapy, which targets multiple levels of an oncogenic signaling cascade or multiple different cell survival pathways, will likely enhance tumor response. In fact, dual immune and molecular therapy together may o ff er the best possibility of both long-term and frequent response25.

Rationale for combination therapy

Newly approved targeted and immune-modulating agents have provided numerous treatment options. However, the optimal sequencing of these agents remains controversial. Even though BRAF inhibition through selective BRAF inhibitors produces excellent early disease control for patients with V600E/K mutations, the response duration of this approach is limited to less than a year because of the development of multiple molecular mechanisms of resistance23,26-32. Checkpo int blo ckade with the CTLA4 inhibitor, ipilimumab, and anti-PD-1 antibodies produces responses in a minority of patients, but with longterm responses13,15. Thus, the combination of targeted therapy and immunotherapy may lead to early and robust antitumor responses from targeted therapy with long-term bene fi t from the in fl uence of immunotherapy.

Preclinical data

In vitrostudies

To date, numerous studies have investigated combined targeted therapy and immunotherapy in melanoma. The first report suggesting that oncogenic BRAFV600Ecan lead to tumoral immune escape was published in 200633. Further in vitro studies have been performed after the development of specific BRAF inhibitors, and BF inhibition in BF mutant melanoma cell lines and fresh tumor digests has been demonstrated to result in up regulation (up to 100-fold) of melanoma differentiation antigens34. Additionally, inhibition with BR AF and MEK inhibitors increased the recognition of these melanoma antigens by antigen-specific T lymphocytes. However, MEK inhibitors adversely affect the T cell function whereas those treated with BR A F inhibito rs maintained functionality34. Further independent studies on the e ff ects of dabrafenib (BF inhibitor), trametinib (MEK inhibitor), or their combination on T lymphocytes have also shown that trametinib alone or in combination suppressed T-lymphocyte proliferation, cytokine production, and antigen-speci fi c expansion, whereas treatment with dabrafenib had no e ff ect35. Callahan et al.36suggested that BF inhibitors can modulate T cell function by potentiating T cell activation through ERK signaling in vitro and in vivo.

In vivostudies

Importantly, the e ff ect of BF inhibition has also been studied in patients with metastatic melanoma. Results showed a similar increase in melanoma differentiation antigens and a significant increase in intratumoral CD8+T cells, which were more clonal10-14 days aer initiation of BF inhibition37-39.ese fi ndings were also associated with down regulated IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)38,40,41.e increased immunomodulatory molecules, PD-1 and PD-L1, 10-14 days after BR AF inhibition initiation are also important, and this condition suggests a potential immune-based mechanism of resistance38.e up regulated PD-L1 expression may have been caused by in fi ltrating IFN-γ-secreting T cells42, although stromal components may also be involved43. Jiang et al.44also suggested PD-L1 expression as a mechanism of resistance to BRAF inhibitors because BRAF-resistant cell lines expressed high PD-L1, and the addition of MEK inhibitors has a suppressive e ff ect on PD-L1 expression.ese data indicate that addition of immunotherapy and specifically immune checkpoint blockade may enhance antitumoral response when combined with a BF inhibitor.

Mouse models have provided important insights into cancer development, treatment, and therapeutic resistance. Several preclinical mouse models have been used to examine in detail the potential of combining immunotherapy with BF-targeted therapy, and most studies have indicated an additive or synergistic effect. In the syngeneic SM1 mouse model of BRAFV600Emelanoma, an improved antitumor activity was observed after combining BF inhibition with adoptively transferred T cells, leading to increased in vivo cytotoxic activity and intratumoral cytokine secretion by the transferred T cells. Interestingly, BF inhibition did not alter adoptively transferred T cell expansion, distribution, or intratumoral density45. Liu et al.41also studied the e ff ects of BF inhibition on adoptively transferred cells by using pmel-1 TCR transgenic mice on a C57BL/6 background and xenografts of melanoma cells transduced with gp100 and H-2Db.ey found an increase in T cell in fi ltration, which was associated with VEGF. Additionally, they showed that melanoma cell VEGF over expression abrogated T cell infiltration, and these findings were validated in patients treated with BRAF-directed therapy considering that down regulated intratumoral VEGF is correlated with a denser intratumoral T cell infiltrate after melanoma patients were treated with BRAF inhibitors41. Knight et al.46utilized several mouse models, which included SM1, SM1WT, and a transgenic mouse model of melanoma, to support the therapeutic potential of combining BF inhibitors and immunotherapy. They observed an increase in CD8:Treg ratio aer BF inhibition and that depleting CD8+T cells, not NK cells, was required for antitumor activity of BF inhibitors.ey also showed that CCR2 demonstrates an antitumoral role after BRAF inhibition and that combination of BRAF-targeted therapy and anti-CCL2 or anti-CD137 led to a significant increase in antitumoral activity in these mouse models46.

However, a previous study has shown the absence of synergy in combined BRAF-targeted and immunotherapy48. This study conducted experiments using a conditional melanocytesp eci fi c expressed BFV600Eand P TEN gene that led to 100% penetrance, short latency, and lymph node and lung metastases.ese induced tumors were similar to human melanoma tumors from a histologic standpoint, but the immune response to BF inhibition was distinct from that observed in BRAF-inhibitortreated patients with metastatic melano ma38,39,48. In this model, treatment with anti-CTLA4 blockade and BRAF inhibition was not associated with improved survival or decreased tumor outgrowth48. These results are contrary to those observed in several other models. Thus, understanding the translational relevance of individual models and their utility in guiding the development of human clinical trials is important.

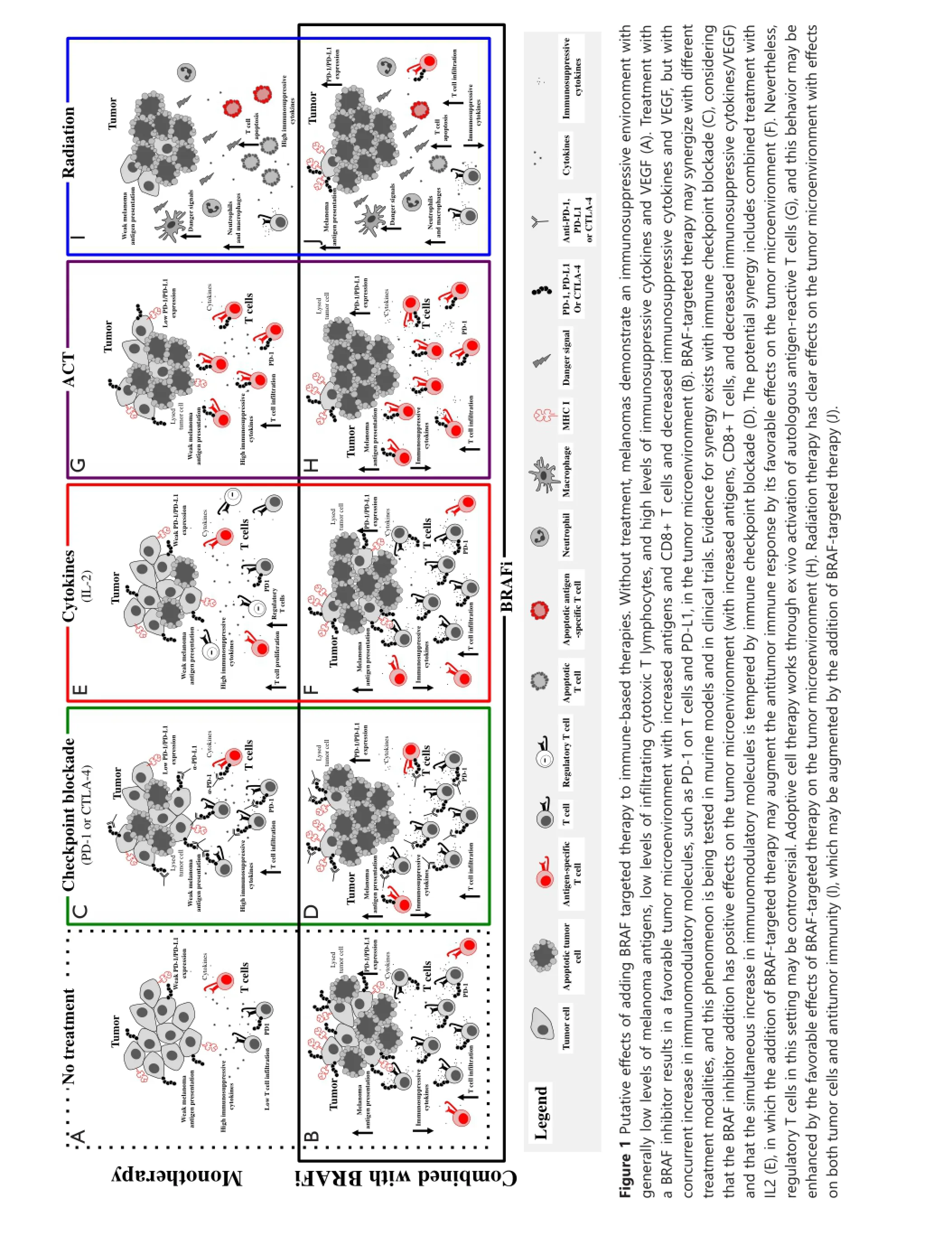

Therefore, combined BRAF-targeted therapy with immunotherapy based on preclinical in vitro and in vivo work is advantageous. Aggregate data suggest that BRAF inhibitor treatment is associated with increased melanoma antigens, increased CD8 T cell in fi ltrate, and decreased immunosuppressive cytokines and VEGF early in the course of therapy (within 2 weeks of initiating treatment in patients)38,40,41. However, a simultaneous increase in immunomodulatory molecules was also found, which may contribute to therapy resistance. Adding BF-targeted therapy to a number of different treatment modalities could improve responses (Figure 1), and these combinations are currently being tested in murine models and clinical trials.

Current and ongoing clinical trials of combined targeted and immunotherapy

Translating the concepts derived from previous studies has aracted much aention for application in patient care seing. However, data on how to treat patients with combined targeted and immunotherapy approaches are insu ffi cient. A phase I study tested the combination of the BF inhibitor vemurafenib with the CTL A4 inhibitor ipilimumab.e fi rst coh ort of 6 patients received full dose vemurafenib at 960 mg orally twice daily for 1 month as a single agent prior to intravenous administrationof ipilimumab at the FDA-approved dose of 3 mg/kg. Dose limiting toxicity (DLT) of grade 3 transaminase elevations were noted in four patients within 2-5 weeks after the first dose of ipilimumab49. A second cohort of patients was then started, in which patients were started on lower dose vemurafenib (720 mg orally twice daily) with full dose ipilimumab. Hepatotoxicity was again observed with grade 3 transaminase elevations in two patients and grade 2 elevation in one patient49. Additionally, one patient in each cohort experienced grade 2 or 3 total bilirubin elevation. All hepatic AEs were asymptomatic and reversible either with temporary discontinuation of both study drugs or with administration of glucocorticoids. Additional AEs of interest included grade 2 temporal arteritis in one patient in cohort 1 and grade 3 rash in two patients in cohort 1.e study was discontinued because of hepatotoxicity issues49.

An ongoing targeted and immunotherapy trial utilizes dabrafenib with or without trametinib combined with ipilimumab in patients with BRAF V600E/K-mutated metastatic melanoma (NCT01767454). At the time of data presentation at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in June 2014, 12 patients had been enrolled on the doublet of ipilimumab with dabrafenib, and 7 patients were enrolled on triplet therapy50. No DLTs were found in the doublet arm of dabrafenib (150 mg) administered orally twice daily and in ipilimumab (3 mg/kg). Thus, a dose expansion of 30 additional patients is ongoing. Although hepatotoxicity was observed in the doublet arm, grade 3 or 4 toxicities were not noted, which is likely due to the lower propensity of hepatotoxicity seen with dabrafenib compared with vemurafenib50. Data are currently insu ffi cient to estimate the duration of bene fi t from doublet therapy.

In the triplet cohort, two cases of colitis associated with colon perforation were noted in the first seven treated patients. Both patients required extensive courses of steroids, and one patient required surgery for management of the colon perforation. Toxicities were observed despite the use of low-dose dabrafenib 100 mg twice daily and trametinib 1 mg daily50. Accrual of patients in this cohort was suspended because of toxicity. Sequential administration of ipilimumab and trametinib in combination with dabrafenib is under consideration.

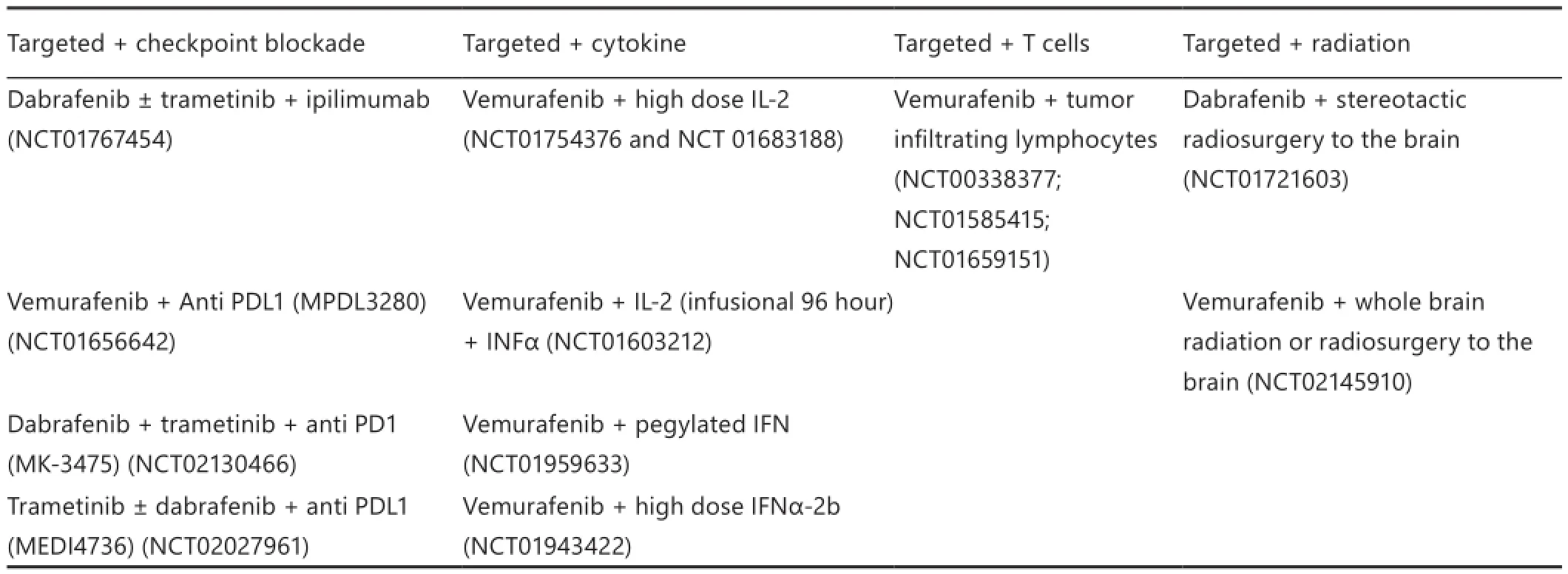

Several other studies that combine targeted therapy and immunotherapy have been planned or are underway, each with varying dose levels and schedules of combination therapy administration (Table 1). These important trials will aid in understanding toxicity p ro fi le and provide preliminary e ffi cacy data of various combinations, including targeted treatment with checkpoint blockade, cytokine therapy, T cell therapy, or radiation. Many of these trials were based on the backbone of dabrafenib- and trametinib-targeted therapy with some variations on the use of BFi or MEKi alone.is condition is expected to establish whether MEKi is truly detrimental when combined with immunotherapy.

The encouraging data regarding checkpoint blockade make these agents ideal for combination with targeted therapy. Given that the side effect profiles, response rates, and durations of response differ among CTLA4, PD-1, and PD-L1 blockers, these trials will be instrumental in providing toxicity and e ffi cacy data. Most of these trials have been designed to involve di ff erent cohorts to determine whether the combination drugs should be started simultaneously or whether targeted therapy should be administered fi rst.

Given that cytokine therapy has long been the primary treatment for advanced stage melanoma, combined targeted treatment and cytokines are currently under clinical investigation. Combination therapy is expected to increase immune recognition o f melan oma cells by CD8 T cells thro ugh u p regulatio n of IFN-αR1 and class I HLA expression. Skin and hepatotoxicity could be overlapping for the vemurafenib and cytokine trials.us, e ffi cacy and toxicity data should be ascertained.

Infusion of TIL for therapeutic benefit in patients is an active area of research interest and is among the most e ff ective immunotherapies in melanoma with approximately 45% ORR51. A murine adoptive cell therapy model was utilized to illustrate that selective BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 could increase tumor infiltration of adoptively transferred T cells and enhance the antitumor activity of the T cells41. This process was mediated by inhibiting the production of VEGF by melanoma cells.is finding was also verified in human melanoma patient tumor samples before and during BF inhibition41. Multiple TIL with targeted therapy trials are ongoing (Table 1).

Selective BRAF inhibitors produce objective responses in patients with CNS disease52. However, data on the combined use of targeted therapy with radiation are insu ffi cient. Although abscopal effect has been reported with use of ipilimumab and concurrent radiation53, this phenomenon has been less well studied with targeted therapy agents. A recent publication has reported a patient with BRAF-mutated melanoma who developed progressive disease in the brain and pelvic lymph nodes after single-agent vemurafenib treatment. Vemurafenib was discontinued, and the patient was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to three CNS metastases, in which imaging showed complete resolution of pelvic nodes 1 month after SRS and no evidence of CNS disease for at least 18 months. The recent use of BRAF inhibitor in this patient was assumed to have facilitated a more favorable tumor microenvironment with enhanced antigen presentation to tumor cells that was augmented with the use of SRS54. Together with plannedimmune correlative studies, these ongoing studies were designed to assess whether the addition of the BRAF-targeted agent improves disease-free survival rate compared with radiation alone to help beer study the hypothesized abscopal e ff ect.

Table 1 Phase I/II studies of combining targeted and immunotherapy in melanoma

Future directions

Metastatic melanoma treatment has been revolutionized over the past few years with the development of immunotherapeutic and targeted agents that improve the OS of patients. Although both immunotherapy and targeted therapies have distinct advantages and disadvantages, preclinical data suggest that combinations of these treatments could further improve patient outcomes. Data of patients who were treated with combined therapy are limited. Response data are therefore insufficient to make conclusions. However, the development of toxicities has been an issue, and controversial questions remain unclear.

The optimal timing and sequence of combination therapy is currently unknown. Trials are being conducted to ascertain whether the agents should be administered simultaneously or targeted agents should be used fi rst to prime the T cell response. Serial biopsies in a single patient on combined vemurafenib and ipilimumab showed increased T cell infiltrate and increase in CD8:Treg ratio, which was transient but increased again after the addition of checkpoint blockade. The presence of CD8 T cell in fi ltrate on day 8 and its marked reduction on day 35 show that initiation of immunotherapy should be applied early in the course of targeted therapy to take advantage of the dense T cell infiltrate early after targeted therapy initiation. This result is limited to a single patient, but has been replicated in the subcutaneous implantable tumor model generated from a wellestablished murine model of BF mutant melanoma47.

Whether the addition of MEK inhibition combined with immune checkpoint blockade (MEK inhibitors) suppresses T cell function in vitro remains debatable34. Studies are currently being conducted to clarify whether this condition will affect potential synergy in vivo. However, existing data suggest that the addition of MEK inhibitors to targeted and immunotherapy combinations may be associated with increased toxicity, given that in a recent study, several patients who underwent dabrafenib, trametinib, and ipilimumab treatment developed AEs related to colonic perforation50. This result, which was unexpected and found in a limited number of patients, highlights the need to further understand the immuno modulatory e ff ects of trametinib.

In summary, metastatic melanoma treatment may have undergone much development, but this progress has resulted in the complexity of managing melanoma patients.e appropriate timing and sequence with molecularly targeted therapy and immunotherapy remains controversial, and synergy is suggested to exist between the two approaches. However, this synergy is tempered by a potential increase in toxicity. Further studies should be performed to increase the understanding of the responses to these types of therapy, and insights gained will help guide optimal management of melanoma patients.

Acknowledgements

Jennifer A. Wargo acknowledges NIH grants 1K08CA160692-01A1, U54CA163125-01 and the generous philanthropic support of several families whose lives have been affected by melanoma.

Con fl ict of interest statement

Jennifer A. Wargo has honoraria from the speakers’ bureau of DAVA Oncology and is an advisory board member for Glaxo Smith Kline, Roche/Genentech, and Amgen. No potential con fl icts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9-29.

4. Costanza ME, Nathanson L, Costello WG, Wolter J, Brunk SF, Colsky J, et al. Results of a randomized study comparing DTIC with TIC mustard in malignant melanoma. Cancer 1976;37:1654-1659.

5. Patel PM, Suciu S, Mortier L, Kruit WH, Robert C, Schadendorf D, et al. Extended schedule, escalated dose temozolomide versus dacarbazine in stage IV melanoma: final results of a randomised phase III study (EORTC 18032). Eur J Cancer 2011;47:1476-1483.

6. Sasse AD, Sasse EC, Clark LG, Ulloa L, Clark OA. Chemoimmunotherapy versus chemotherapy for metastatic malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD005413.

7. Ives NJ, Stowe RL, Lorigan P, Wheatley K. Chemotherapy compared with biochemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis of 18 trials involving 2,621 patients. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5426-5434.

8. Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2105-2116.

9. Atkins MB, Kunkel L, Sznol M, Rosenberg SA. High-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: long-term survival update. Cancer J Sci Am 2000;6 Suppl 1:S11-S14.

10. Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, Conry RM, Miller DM, Treisman J, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2119-2127.

12. Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Wunderlich JR, Dudley ME, White DE, et al. Tumor antigen-speci fi c CD8 T cells in fi ltrating the tumor express high levels of PD-1 and are functionally impaired. Blood 2009;114:1537-1544.

13. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermoDF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711-723.

15. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Geinger SN, Smith DC, McDermoDF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443-2454.

16. Ribas A , Hodi FS, Ke ff ord R, Hamid O, Daud A, Wolchok JD, et al. E ffi cacy and safety of the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody MK-3475 in 411 patients (pts) with melanoma (MEL). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr LBA9000.

17. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2455-2465.

18. Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:122-133.

19. Sznol M, Kluger HM, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Gordon, Segal NH, et al. Survival, response duration, and activity by BF mutation (MT) status of nivolumab (NIVO, anti-PD-1, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) and ipilimumab (IPI) concurrent therapy in advanced melanoma (MEL). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr LBA9003.

20. Davies MA, Stemke-Hale K, Lin E, Tellez C, Deng W, Gopal YN, et al. Integrated Molecular and Clinical Analysis of AKT Activation in Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:7538-7546.

21. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2507-2516.

22. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, et al. Dabrafenib in BF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:358-365.

23. Johannessen CM, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Thomas SR, Wardwell L, Johnson L A, et al. COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature 2010;468:968-972.

24. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A , Gonzalez R, Ke ff ord RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1694-1703.

25. Gorantla VC, Kirkwood JM. State of melanoma: an historic overview of a fi eld in transition. Hematol Oncol Clin North A m 2014;28:415-435.

26. Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, et al.Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature 2010;468:973-977.

27. Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature 2012;487:500-504.

28. Montagut C, Sharma SV, Shioda T, McDermoU, Ulman M, Ulkus LE, et al. Elevated CF as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to BF inhibition in melanoma. Cancer Res 2008;68:4853-4861.

29. Emery CM, Vijayendran KG, Zipser MC, Sawyer AM, Niu L, Kim JJ, et al. MEK1 mutations confer resistance to MEK and B-F inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20411-20416.

31. Shi H, Moriceau G, Kong X, Lee MK, Lee H, Koya RC, et al. Melanoma whole-exome sequencing identi fi es (V600E)B-F ampli fi cation-mediated acquired B-F inhibitor resistance. Nat Commun 2012;3:724.

32. Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, et al.F inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BF(V600E). Nature 2011;480:387-390.

33. Sumimoto H, Imabayashi F, Iwata T, Kawakami Y.e BFMAPK signaling pathway is essential for cancer-immune evasion in human melanoma cells. J Exp Med 2006;203:1651-1656.

34. Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, et al. Selective BFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without a ff ecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res 2010;70:5213-5219.

35. Vella LJ, Pasam A, Dimopoulos N, Andrews M, Knights A, Puaux AL,et al. MEK inhibition, alone or in combination with BF inhibition, a ff ects multiple functions of isolated normal human lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:351-360.

36. Callahan MK, Masters G, Pratilas CA, Ariyan C, Katz J, Kitano S, et al. Paradoxical activation of T cells via augmented ERK signaling mediated by aF inhibitor. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:70-79.

37. Cooper ZA, Frederick DT, Juneja VR, Sullivan RJ, Lawrence DP, Piris A, et al. BF inhibition is associated with increased clonality in tumor-in fi ltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology 2013;2:e26615.

38. Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, Cooper ZA, Lezcano C, Ferrone CR, et al. BF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:1225-1231.

40. Khalili JS, Liu S, Rodríguez-Cruz TG, Whiington M, Wardell S, Liu C, et al. Oncogenic BF(V600E) promotes stromal cellmediated immunosuppression via induction of interleukin-1 in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:5329-5340.

41. Liu C, Peng W, Xu C, Lou Y, Zhang M, Wargo JA, et al. BF inhibition increases tumor in fi ltration by T cells and enhances the antitumor activity of adoptive immunotherapy in mice. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:393-403.

42. Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, Williams J, Meng Y, Ha, et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and T(regs) in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8(+) T cells. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:200ra116.

43. Frederick DT, Ahmed Z, Cooper ZA, Lizee G, Hwu P, Ferrone CR, et al. Stromal fi broblasts contribute to the up-regulation of PD-L1 in melanoma aer BF inhibition. Society For Melanoma Research 2013 International Congress; 2013; Philadelphia, PA; 2013:950-1.

44. Jiang X, Zhou J, Giobbie-Hurder A, Wargo J, Hodi FS.e activation of MAPK in melanoma cells resistant to BF inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression that is reversible by MEK and PI3K inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:598-609.

46. Knight DA, Ngiow SF, Li M, Parmenter T, Mok S, Cass A, et al. Host immunity contributes to the anti-melanoma activity of BF inhibitors. J Clin Invest 2013;123:1371-1381.

47. Cooper ZA, Juneja VR, Sage PT, Frederick DT, Piris A, Mitra D, et al. Response to BF inhibition in melanoma is enhanced when combined with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:643-654.

48. Hooijkaas A, Gadiot J, Morrow M, Stewart R, Schumacher T, Blank CU. Selective BF inhibition decreases tumor-resident lymphocyte frequencies in a mouse model of human melanoma. Oncoimmunology 2012;1:609-617.

49. Ribas A, Hodi FS, Callahan M, Konto C, Wolchok J. Hepatotoxicity with combination of vemurafenib and ipilimumab. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1365-1366.

50. Puzanov I, Callahan MK, Linee GP, Patel SP, Luke JJ, Sosman JA, et al. Phase 1 study of the BF inhibitor dabrafenib (D) with or without the MEK inhibitor trametinib (T) in combination with ipilimumab (Ipi) for V600E/K mutation–positive unresectable or metastatic melanoma (MM). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr 2511.

51. Radvanyi LG, Bernatchez C, Zhang M, Fox PS, Miller P, Chacon J, et al. Speci fi c lymp ho cyte subsets predict resp onse to ad optive cell therapy using expanded autologous tumor-in fi ltrating lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6758-6770.

52. Falchook GS, Long GV, Kurzrock R, Kim KB, Arkenau TH, Brown MP, et al. Dabrafenib in patients with melanoma, untreated brain metastases, and other solid tumours: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2012;379:1893-1901.

53. Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal e ff ect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012;366:925-931.

54. Sullivan RJ, Lawrence DP, Wargo JA, Oh KS, Gonzalez RG, Piris A. Case records of the Massachuses General Hospital. Case 21-2013. A 68-year-old man with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:173-183.

Cite this article as:Kim T, Amaria RN, Spencer C, Reuben A, Cooper ZA, Wargo JA. Combining targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Biol Med 2014;11:237-246. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.04.002

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Zachary A. Cooper and Jennifer A. Wargo

E-mail: zcooper@mdanderson.org and jwargo@mdanderson.org Received September 9, 2014; accepted October 13, 2014.

Available at www.cancerbiomed.org

Copyright ? 2014 by Cancer Biology & Medicine

Cancer Biology & Medicine2014年4期

Cancer Biology & Medicine2014年4期

- Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- Sequential maximum androgen blockade (MAB) in minimally symptomatic prostate cancer progressing after initial MAB: two case reports

- E ff ect of EGFR-TKI retreatment following chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who underwent EGFR-TKI

- Argyrophilic nucleolar organizer region in MIB-1 positive cells in non-small cell lung cancer: clinicopathological signi fi cance and survival

- Emerging function of mTORC2 as a core regulator in glioblastoma: metabolic reprogramming and drug resistance

- Recent advances in lymphatic targeted drug delivery system for tumor metastasis

- Minimally invasive local therapies for liver cancer