Pancreatic head cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis

Aude Merdrignac, Laurent Sulpice, Michel Rayar, Tanguy Rohou, Emmanuel Quéhen, Ayman Zamreek, Karim Boudjema and Bernard Meunier

Rennes, France

Pancreatic head cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis

Aude Merdrignac, Laurent Sulpice, Michel Rayar, Tanguy Rohou, Emmanuel Quéhen, Ayman Zamreek, Karim Boudjema and Bernard Meunier

Rennes, France

BACKGROUND:Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a risk factor of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA). The discovery of a pancreatic head lesion in CP frequently leads to a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) which preceded by a multidisciplinary meeting (MM). The aim of this study was to evaluate the relevance between this indication of PD and the definitive pathological results.

METHODS:Between 2000 and 2010, all patients with CP who underwent PD for suspicion of PA without any histological proof were retrospectively analyzed. The operative decision has always been made at an MM. The definitive pathological finding was retrospectively confronted with the decision made at an MM, and patients were classified in two groups according to this concordance (group 1) or not (group 2). Clinical and biological parameters were analyzed, preoperative imaging were reread, and confronted to pathological findings in order to identify predictive factors of malignant degeneration.

RESULTS:During the study period, five of 18 (group 1) patients with CP had PD were histologically confirmed to have PA, and the other 13 (group 2) did not have PA. The median age was52.5 ±8.2 years (gender ratio 3.5). The main symptoms were pain (94.4%) and weight loss (72.2%). There was no patient's death. Six (33.3%) patients had a major complication (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥3). There was no statistical difference in clinical and biological parameters between the two groups. The rereading of imaging data could not detect efficiently all patients with PA.

CONCLUSIONS:Our results confirmed the difficulty in detecting malignant transformation in patients with CP before surgery and therefore an elevated rate of unnecessary PD was found. A uniform imaging protocol is necessary to avoid PD as a less invasive treatment could be proposed.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:192-197)

chronic pancreatitis;

adenocarcinoma;

pancreaticoduodenectomy

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a risk factor for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA), with a 5- and 10-year cumulative incidences of 1.1% and 1.7% respectively in large cohort studies.[1,2]The median 5-year survival rate after diagnosis of PA is 4%-6% (all stages combined),[3,4]and surgery remains the only potential curative treatment.[5,6]

The diagnosis of PA is relatively simple in the pancreatic body or tail, but is still difficult within a hypertrophic calcified head remodeled by CP. Then, the diagnosis of PA is often made only by imaging findings without histological proof related to the difficulty in obtaining adequate biopsy tissue with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).[7]Nevertheless, the prognosis of malignant degeneration is so poor that pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is mandatory. The difficulty of this situation is to balance the risk of misdiagnosing a malignant transformation and the high morbidity (30%-70%) associated with PD.[8-10]

In our center, surgical indication is always discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting (MM). The main objective of this retrospective study was to analyze the degree of concordance between indications of PD for PA in patients with CP without histological proof and definitive pathological findings. Secondary objectives were to identify preoperative clinical and biological factors that could be predictive of malignant degeneration, and to evaluate radiological expertise in this situation.

Methods

Patients

After approval by our institutional review board, all data of patients who had undergone PD from January 2000 to December 2010 in our tertiary center of pancreatic surgery were collected and retrospectively analyzed.

Inclusion criteria were the presence of both CP and a focal head pancreatic lesion (either at diagnosis of CP or during follow-up), suspected to be a PA without histological proof (e.g. EUS biopsies unrealizable or noncontributive). The indications of PD were established by an MM with the participation of gastroenterologists, gastrointestinal surgeons, and radiologists who reinterpreted patient's imaging. The main criterion for decision-making was based on imaging findings (contrast enhancement, presence of bulky lymph nodes and aspect of retroportal lamina). Thereby, patients diagnosed as having PA based on preoperative histology were excluded.

The clinical and biological data collected preoperatively were: age, gender, smoking habits, alcohol intake, symptoms, duration between the diagnosis of CP and the suspicion of PA, and blood work-up results (aminotransferases, total and conjugated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatases, and C-reactive protein).

The preoperative imagings available included endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), upper gastrointestinal EUS, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan was not used routinely in our center. The postoperative data analyzed were as follows: length of hospital stay, morbidity, mortality, and pathological findings.

Definitions

Postoperative mortality was defined as death during the hospital stay or within 30 days after surgery. Postoperative morbidity was defined according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.[11]Postoperative complications included: pancreatic fistula classified into three groups according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) criteria,[12]delayed gastric emptying (DGE) classified according to the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) criteria[13]but only those with grade B and C retained for this study, as our center policy was to maintain the nasogastric tube until at least postoperative day 5, postpancreatectomy hemorrhage including intra and extra luminal bleeding classified according to the ISGPS definition,[14]and biliary fistula defined by biliary leakage in drains.

Methods

The impact of radiological expertise was measured by a secondary analysis of available imaging documents (presence or absence of PA) performed by 2 senior radiologists both specialized in abdominal imaging. The two radiologists were both blinded to the pathological data and the previous radiological reports. Expert status has been defined as an experience in abdominal imaging over 5 years. Preoperative imaging documents reviewed were CT, MRCP and ERCP. The radiologists paid a particular attention to pancreatic trophicity (head, body and tail), characteristics of main pancreatic and biliary ducts (size, regularity), characteristics of pancreatic head nodules (localization, size), aspect of retroportal lamina, presence of pancreatic calcifications and peripancreatic infiltration, pseudocysts or lymph nodes.

The patients were divided into two groups according to pathological findings: group 1, CP+PA and group 2, CP alone. Univariate analysis was used to identify clinical and biological factors which are predictive of PA.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as median and compared with Wilcoxon's rank-sum test as appropriate. Qualitative data were expressed as numbers and percentages in each group of patients and compared with Fisher's exact test. When a significant difference was found between the two groups, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to identify a threshold value.

Statistical analysis was carried out by MATLAB version 7.11 (MathWorks Inc., MA, USA). APvalue <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 314 patients underwent PD during the study period. Among them, 18 (5.7%) patients with suspected PA had CP, and the analysis was based on these 18 patients.

Clinical, biological and imaging findings

The median age of the patients was 52.5±8.2 years, and the male/female ratio was 3.5. The median duration of follow-up for CP before suspicion of PA was 9.5 months. The underlying cause of CP was alcohol (n=12), cryptogenic (n=4) and genetic disease (n=2).

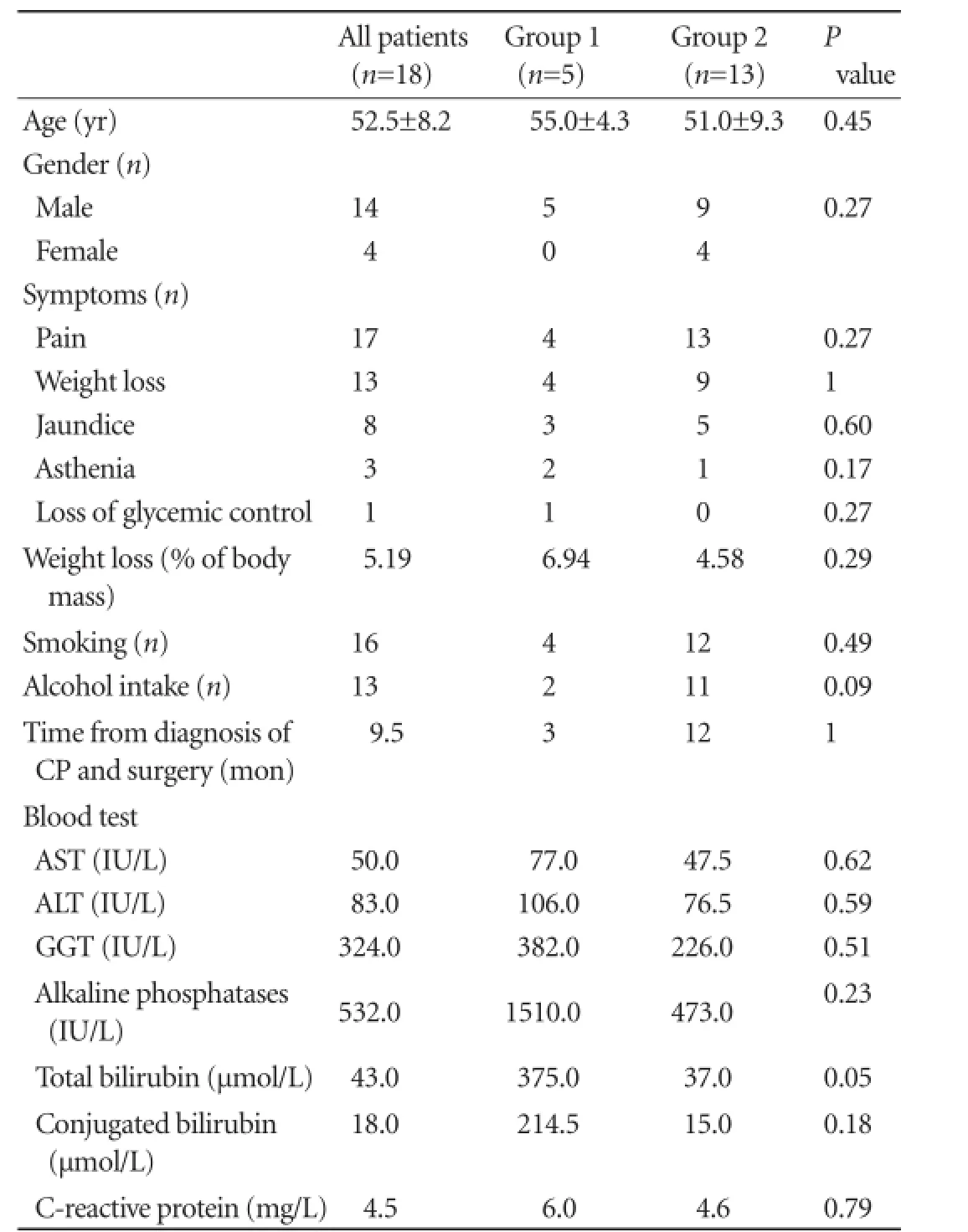

The clinical signs were pain (n=17), weight loss (n=13), jaundice (n=8), asthenia (n=3), and glycemic disorder (n=1) (Table 1). The median levels of preoperative tumor biomarkers were 2.9 (range 1.7-6.9) and 13 (range 3-2056) for CEA and CA19-9, respectively. As these data were only available for 10 patients of the study population, we could not test them in the statistical analysis.

The preoperative imagings analyzed were abdominal CT for 16 patients, upper gastrointestinal EUS for 12, MRCP for 7, and ERCP for 5 .

The mean head nodule size (only available for 14 patients) was 1.8±0.4 cm (range 1.2-2.5).

The EUS was particularly helpful in 10 patients of our series. It confirmed the presence of nodular lesions at CT scan or MRCP in 5 patients, identified small nodular lesions in the pancreatic head (not seen by CT scan or MRCP) in 4; and detected one lymph node not seen with CT scan in 1.

MRCP and ERCP were valuable in detecting abnormalities of the main bile duct. Indeed, ERCP identified 2 irregularities and 3 strictures (complete in 1 patient, and partial in 2) of the main bile duct whereas MRCP identified 5 strictures (2 complete and 3 partial).

Postoperative morbidity

Postoperative complications presented according to the Clavien-Dindo classification are listed in Tables 2, 3. There was no patient's death. The overall morbidity was 61.1% including patients with a major complication (Clavien-Dindo classification ≥3). Four patients required surgical reintervention: 1 for hemorrhage, 1 for biliary, 1 for pancreatic fistula and 1 for both hemorrhage and biliary fistula. These patients belonged to group 2. Gastrojejunal anastomosis bleeding occurred in another patient in group 2, who was treated endoscopically.

Pathological results

Histological examination confirmed the presence of PA in 5 of the 18 patients.

Predictive factors

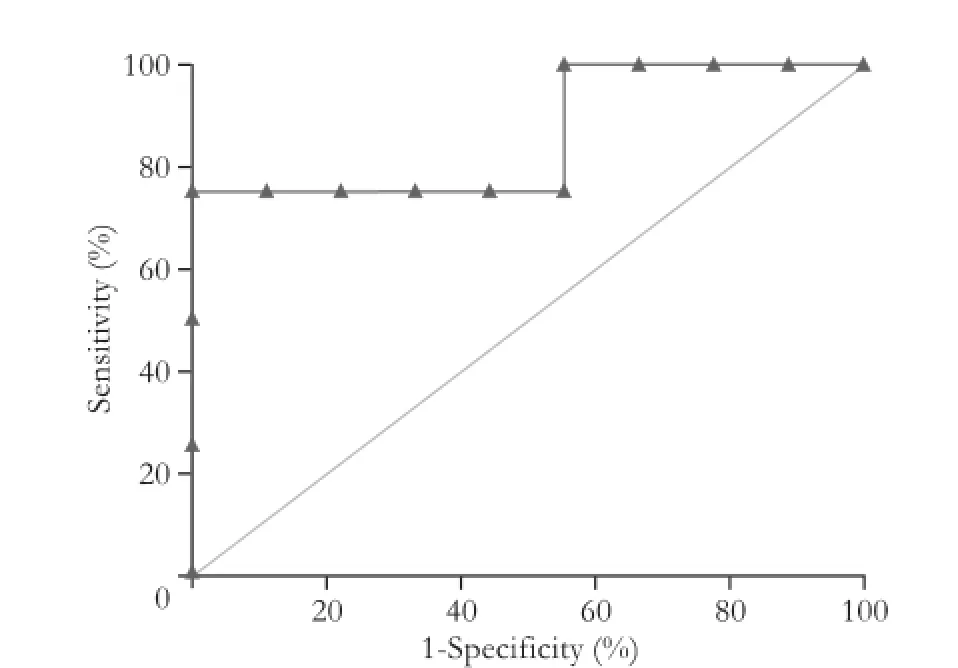

Univariate analysis revealed only one difference between the two groups: total bilirubin level was higher in group 1 than in group 2 (375 vs 37 μmol/L,P=0.05) (Table 1). The threshold was 355 μmol/L, which was determined by the ROC (Fig.) with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 100%.

Table 1.Preoperative clinical and biological data in the two groups of patients

Table 2.Postoperative complications and duration of hospital stay (mean±SD) of patients

Table 3.Distribution of complications in the two groups according to the Clavien-Dindo classification

Fig.ROC of the total bilirubin rate for diagnosis of PA.

Impact of radiological expertise

Only 14 patients (10 patients in group 1 and 4 in group 2) were subjected to imaging for second radiological reading. The previous reading did not detect PA in all patients. The first radiologist observed malignant lesions in 2 patients who actually had PA, benign lesions in 10 patients, and un-defined lesion in 2 patients. The second radiologist found malignant lesions in 5patients, including 3 who actually had PA, benign lesions in 7 patients, and un-defined lesions in 2 patients.

Discussion

CP is an independent risk factor for PA. The cumulative risk of PA is 1.8% and 4% at 10 and 20 years respectively.[15]To date, no guidelines have yet been published regarding the imaging follow-up,[16,17]nevertheless this turning point in the evolution of CP justified to establish a radiological monitoring. The diagnosis of head localized PA is a serious challenge in patients with CP. This difficult situation represents 5.7% of the PDs performed during the study period.

Our analysis showed that most of these decisions were incorrect. Indeed, the pathological examinations of surgical specimens revealed that 72.2% of these patients were PA free whereas 5%-9% has no underlying CP.[18,19]These inappropriate decisions had major consequences since the postoperative morbidity was 61.1 % (including 33.3% Clavien-Dindo classification ≥3) for these patients. Similar rates have been previously reported.[20]

This hard decision-making process is hampered by the lack of informative clinical and biological data, as there are no specific signs differentiating PA and CP progression. In fact, our results showed no significant difference between our two groups in terms of clinical presentation as described previously.[18,21]However, our results revealed higher levels of total bilirubin in the patients from group 1 at the borderline of statistical significance (P=0.05).

In addition, there is no consensus on tumor markers assay.[22,23]CA19-9 would be the most sensitive marker but it can be valueless in context of cholestasis.[24]To improve the sensitivity, some studies have proposed to associate K-ras gene mutation searching in the circulating DNA. The presence of this mutation, combined with an elevated CA19-9, would be associated with a sensitivity of 95%.[25,26]

In clinical practice, however, radiological and EUS findings provide the key to diagnosis. For healthy pancreas, abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast is the gold standard examination, both for diagnosis and disease spread.[27]EUS is more sensitive, especially to small sized tumors, and also allows biopsy taking.[28]But in the context of CP, the sensitivity of EUS is only 54%-74%.[29,30]Nowadays, new EUS combined with enhanced contrast or elastography showed promising results but it still needs prospective studies to validate.[31,32]

Because of the presence of parenchymatous calcifications and pancreatic head hypertrophy in CP, imaging interpretation is limited.[33]In order to improve the sensitivity of radiological explorations, specific magnetic resonance sequences (T1-weighted echo-gradient with gadolinium injection, T2-weighted turbo-spin echo) have been developed.[34]Similarly, the response to secretin has been used to highlight diminished exocrine function due to apparently tumor-related stricture of the main pancreatic canal.[35,36]Recently, diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been tested in this indication and has shown significantly lower coefficients of diffusion in patients with PA.[37]Studies[38,39]have shown the potential usefulness of FDG-PET in this context with a sensitivity of 83%-86%.

Because of lack of specificity of imaging explorations, Gerstenmaier et al[40]proposed an evidence-based decision-making algorithm applying the statistical probabilities of pre- and post-examination malignancy described in the literature. The algorithm starts with an abdominal CT followed by an MRCP if positive. No further exploration is necessary if both CT and theMRCP are negative; a follow-up with a regular abdominal CT can be proposed. In case of positive MRCP, EUS is performed, followed by FDG-PET if it is negative.

In our study, the rereading of images could not detect all the patients with PA although the radiologists had more time for interpretation and were free from the pressure of the MM. Nevertheless, the main limitation is that our study period was extended (10 years) and that all the different types of imaging were not available for all patients (explaining the lack of uniformly imaging protocol). The heterogeneity of the imaging protocols could explain the high number of false positive. Currently, we have performed systematic realization of FDG-PET and diffusion MRI in order to improve the decision of MM in addition to systematic biomarkers assays (CA19-9 and CEA).

We expected to find a successful attitude that will limit the number of unnecessary PD, and eventually propose to these symptomatic patients an appropriate endoscopic or other surgical treatment (i.e. Frey or Beger procedure), which are associated with a lower morbidity (10%-30% and 20%-40% for the Frey and Beger procedures, respectively).[41-43]

In summary, our results were in line with the literature and confirmed the difficulty encountered to establish an accurate diagnosis of PA in patients with CP. Consequently, the doubt about diagnosis leads to an over-indication of PD at the MM. This study confirms the necessity of a uniform validated imaging protocol to improve the decision-making process at the MM.

Contributors:SL proposed the study. MA and SL performed research and wrote the first draft. MA and SL have equally participated to this article. MA collected and analyzed the data. RT and QE collected imaging data. RM and ZA corrected manuscript. BK revised the manuscript. MB revised the manuscript and gave final approval for publication. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. SL is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Malka D, Hammel P, Maire F, Rufat P, Madeira I, Pessione F, et al. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in chronic pancreatitis. Gut 2002;51:849-852.

2 Karlson BM, Ekbom A, Josefsson S, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF Jr, Nyrén O. The risk of pancreatic cancer following pancreatitis: an association due to confounding? Gastroenterology 1997;113:587-592.

3 Cleary SP, Gryfe R, Guindi M, Greig P, Smith L, Mackenzie R, et al. Prognostic factors in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: analysis of actual 5-year survivors. J Am Coll Surg 2004;198: 722-731.

4 Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:277-300.

5 Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2011;378:607-620.

6 Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:267-277.

7 Krishna NB, Mehra M, Reddy AV, Agarwal B. EUS/EUSFNA for suspected pancreatic cancer: influence of chronic pancreatitis and clinical presentation with or without obstructive jaundice on performance characteristics. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:70-79.

8 Huguier M, Mason NP. Treatment of cancer of the exocrine pancreas. Am J Surg 1999;177:257-265.

9 Sch?fer M, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA. Evidence-based pancreatic head resection for pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 2002;236:137-148.

10 Russell RC, Theis BA. Pancreatoduodenectomy in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. World J Surg 2003;27:1203-1210.

11 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

12 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

13 Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761-768.

14 Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 2007;142:20-25.

15 Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1433-1437.

16 Frulloni L, Falconi M, Gabbrielli A, Gaia E, Graziani R, Pezzilli R, et al. Italian consensus guidelines for chronic pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis 2010;42:S381-406.

17 Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Morselli-Labate AM, Maisonneuve P, Pezzilli R. Pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis; aetiology, incidence, and early detection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010;24:349-358.

18 van Gulik TM, Reeders JW, Bosma A, Moojen TM, Smits NJ, Allema JH, et al. Incidence and clinical findings of benign, inflammatory disease in patients resected for presumed pancreatic head cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 1997;46:417-423.

19 de Castro SM, de Nes LC, Nio CY, Velseboer DC, ten Kate FJ, Busch OR, et al. Incidence and characteristics of chronic and lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis in patients scheduled to undergo a pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB(Oxford) 2010;12:15-21.

20 Enestvedt CK, Diggs BS, Cassera MA, Hammill C, Hansen PD, Wolf RF. Complications nearly double the cost of care after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2012;204:332-338.

21 Evans JD, Morton DG, Neoptolemos JP. Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Postgrad Med J 1997;73:543-548.

22 Goggins M. Identifying molecular markers for the early detection of pancreatic neoplasia. Semin Oncol 2007;34:303-310.

23 Duffy MJ, Sturgeon C, Lamerz R, Haglund C, Holubec VL, Klapdor R, et al. Tumor markers in pancreatic cancer: a European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM) status report. Ann Oncol 2010;21:441-447.

24 Singh S, Tang SJ, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Lara LF, Siddiqui A. The clinical utility and limitations of serum carbohydrate antigen (CA19-9) as a diagnostic tool for pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2491-2496.

25 Maire F, Micard S, Hammel P, Voitot H, Lévy P, Cugnenc PH, et al. Differential diagnosis between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: value of the detection of KRAS2 mutations in circulating DNA. Br J Cancer 2002;87:551-554.

26 Theodor L, Melzer E, Sologov M, Idelman G, Friedman E, Bar-Meir S. Detection of pancreatic carcinoma: diagnostic value of K-ras mutations in circulating DNA from serum. Dig Dis Sci 1999;44:2014-2019.

27 McNulty NJ, Francis IR, Platt JF, Cohan RH, Korobkin M, Gebremariam A. Multi--detector row helical CT of the pancreas: effect of contrast-enhanced multiphasic imaging on enhancement of the pancreas, peripancreatic vasculature, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Radiology 2001;220:97-102.

28 Tamm EP, Loyer EM, Faria SC, Evans DB, Wolff RA, Charnsangavej C. Retrospective analysis of dual-phase MDCT and follow-up EUS/EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Abdom Imaging 2007;32:660-667.

29 Fritscher-Ravens A, Brand L, Kn?fel WT, Bobrowski C, Topalidis T, Thonke F, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for focal pancreatic lesions in patients with normal parenchyma and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2768-2775.

30 Varadarajulu S, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA. Yield of EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic masses in the presence or the absence of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62: 728-736; quiz 751, 753.

31 Gheonea DI, Streba CT, Ciurea T, S?ftoiu A. Quantitative low mechanical index contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for the differential diagnosis of chronic pseudotumoral pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. BMC Gastroenterol 2013;13:2.

32 S?ftoiu A, Iordache SA, Gheonea DI, Popescu C, Malo? A, Gorunescu F, et al. Combined contrast-enhanced power Doppler and real-time sonoelastography performed during EUS, used in the differential diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:739-747.

33 Oto A, Eltorky MA, Dave A, Ernst RD, Chen K, Rampy B, et al. Mimicks of pancreatic malignancy in patients with chronic pancreatitis: correlation of computed tomography imaging features with histopathologic findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2006;35:199-205.

34 Kim JK, Altun E, Elias J Jr, Pamuklar E, Rivero H, Semelka RC. Focal pancreatic mass: distinction of pancreatic cancer from chronic pancreatitis using gadolinium-enhanced 3D-gradient-echo MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;26:313-322.

35 Matos C, Bali MA, Delhaye M, Devière J. Magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of pancreatitis and pancreatic neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006;20:157-178.

36 Klauss M, Lemke A, Grünberg K, Simon D, Re TJ, Wente MN, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion MRI for the differentiation between mass forming chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Invest Radiol 2011;46:57-63.

37 Fattahi R, Balci NC, Perman WH, Hsueh EC, Alkaade S, Havlioglu N, et al. Pancreatic diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI): comparison between mass-forming focal pancreatitis (FP), pancreatic cancer (PC), and normal pancreas. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;29:350-356.

38 van Kouwen MC, Jansen JB, van Goor H, de Castro S, Oyen WJ, Drenth JP. FDG-PET is able to detect pancreatic carcinoma in chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005;32:399-404.

39 Singer E, Gschwantler M, Plattner D, Kriwanek S, Armbruster C, Schueller J, et al. Differential diagnosis of benign and malign pancreatic masses with 18F-fluordeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography recorded with a dual-head coincidence gamma camera. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:471-478.

40 Gerstenmaier JF, Malone DE. Mass lesions in chronic pancreatitis: benign or malignant? An "evidence-based practice" approach. Abdom Imaging 2011;36:569-577.

41 Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Kuechler T, Binmoeller KF, Broelsch CE. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 1995;221:350-358.

42 Keck T, Wellner UF, Riediger H, Adam U, Sick O, Hopt UT, et al. Long-term outcome after 92 duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections for chronic pancreatitis: comparison of Beger and Frey procedures. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:549-556.

43 Regimbeau JM, Dumont F, Yzet T, Chatelain D, Bartoli ER, Brazier F, et al. Surgical management of chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;31:672-685.

Received April 15, 2013

Accepted after revision September 18, 2013

Author Affiliations: Service de Chirurgie Hépatobiliaire et Digestive, H?pital Pontchaillou, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France (Merdrignac A, Sulpice L, Rayar M, Zamreek A, Boudjema K and Meunier B); Service d'Imagerie Médicale, H?pital Pontchaillou, Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France (Rohou T and Quéhen E); INSERM UMR991, Foie, Métabolismes et Cancer, Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France (Sulpice L and Boudjema K)

Laurent Sulpice, MD, Service de Chirurgie Hépatobiliaire et Digestive, H?pital Pontchaillou, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Université de Rennes 1, Rennes, France (Tel: 33-299-28-42-65; Fax: 33-299-28-41-29; Email: laurent.sulpice@chu-rennes.fr)

This work has been presented as a displayed communication to IHPBA, Paris, July 2012.

? 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60030-8

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Improved anterior hepatic transection for isolated hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate

- Instrumental detection of cystic duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Familial chylomicronemia syndrome related chronic pancreatitis: a single-center study

- Pancreatic fistula after central pancreatectomy: case series and review of the literature

- Multi-visceral resection of locally advanced extra-pancreatic carcinoma

- FBW7 increases chemosensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through suppression of epithelialmesenchymal transition