Familial chylomicronemia syndrome related chronic pancreatitis: a single-center study

Gurhan Sisman, Yusuf Erzin, Ibrahim Hatemi, Erkan Caglar, Salih Boga, Vikesh Singh and Hakan Senturk

Istanbul, Turkey

Familial chylomicronemia syndrome related chronic pancreatitis: a single-center study

Gurhan Sisman, Yusuf Erzin, Ibrahim Hatemi, Erkan Caglar, Salih Boga, Vikesh Singh and Hakan Senturk

Istanbul, Turkey

BACKGROUND:Hypertriglyceridemia induces acute recurrent pancreatitis, but its role in the etiology of chronic pancreatitis (CP) is controversial. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical, laboratory and radiological findings of 7 patients with CP due to type 1 hyperlipidemia compared to CP patients with other or undefined etiological factors.

METHODS:We retrospectively analyzed the clinical, laboratory and radiological findings of 7 CP patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia compared to CP patients without hypertriglyceridemia. These 7 patients had multiple episodes of acute pancreatitis and had features of CP on abdominal CT, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and/or endoscopic ultrasonography.

RESULTS:All CP patients were classified into two groups: a group with type 1 hyperlipidemia (n=7) and a group with other etiologies (n=58). The mean triglyceride level was 2323±894 mg/dL in the first group. Age at the diagnosis of CP in the first group was significantly younger than that in the second group (16.5±5.9 vs 48.3±13.5,P<0.001). The number of episodes of acute pancreatitis in the first group was significantly higher than that in the second group (15.0±6.8 vs 4.0±4.6,P=0.011). The number of splenic vein thrombosis in the first group was significantly higher than that in the second group (4/7 vs 9/58,P=0.025). Logistic regression analysis found that younger age was an independent predictor of CP due to hypertriglyceridemia (r=0.418,P=0.000).CONCLUSIONS:Type 1 hyperlipidemia appears to be an etiological factor even for a minority of patients with CP. It manifests at a younger age, and the course of the disease might be severe.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:209-214)

chronic pancreatitis;

hyperlipidemia;

treatment

Introduction

The etiology of chronic pancreatitis (CP) has changed over time and is multifactorial in some cases.[1]Therefore, it would be more accurate to use the term "chronic pancreatitis" and list the existing risk factors.[2]

Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) pancreatitis is generally seen in patients who have serum triglyceride levels higher than 1000 mg/dL (11.3 mmol/L).[3,4]Primary (genetic) or secondary disorders of lipoprotein metabolism (e.g., diabetes, obesity, hypothyroidism, drugs) may cause HTG pancreatitis. Type 1 hyperlipidemia is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by xanthomatosis, lipemia retinalis and hepatosplenomegaly. The diagnosis of HTG pancreatitis is based on the demonstration of decrease or absence of lipoprotein lipase and activator apolipoprotein (apo)-C-II. Clinical manifestations of HTG pancreatitis can be seen in the early adulthood.[5,6]These manifestations are similar to those of pancreatitis due to other causes. HTG may cause recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, but little data are available to support that HTG might cause CP. In fact, a link to any kind of pancreatitis was shown for alcoholism, smoking and genetic tendency.[7]

In this study, clinical, laboratory and radiological findings of seven type 1 hyperlipidemia patients with CP were summarized and compared with patients with CP caused by other or undefined etiological factors.

Methods

Clinical, laboratory, endoscopic and radiological findings of 65 CP patients who had been treated in our gastroenterology department from 2007 to 2011 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were classified into two groups: CP patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia (n=7, HTG group) and CP patients with other etiologies (n=58, non-HTG group). The 7 patients had multiple attacks of pancreatitis and had features of CP on abdominal CT, MRCP, ERCP and/or EUS. Type 1 hyperlipidemia was diagnosed by a decrease or absence of lipoprotein lipase activation in plasma after 12-hour fasting, administration of heparin or demonstration of apo-CII deficiency. All CP patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia received an intravenous injection of 100 U heparin/kg body weight, and postheparin blood sample was drawn after 10 minutes of rest. Lipoprotein lipase activity was expressed as micromoles of free fatty acids (FFAs) released per milliliter of postheparin plasma per hour (μmol FFA/mL per hour).[8]Other etiological factors and possibility of hereditary pancreatitis (presence of PRSS1, SPINK1 and CFTR mutations) were evaluated in both groups. As an etiological factor, smoking was compared between the two groups. Factors like alcohol consumption, obesity, hypothyroidism, pregnancy, nephrotic syndrome, use of certain medications like estrogens, tamoxifen, β-blockers, and glucocorticoids which may lead to secondary HTG were eliminated.

Acute pancreatitis was defined by the presence of the following criteria: typical abdominal pain and serum lipase greater than three times of the upper normal limit or evidence of pancreatitis on CT according to Balthazar's classification.[9]Severe acute pancreatitis was defined by using the Atlanta classification.[10]Alcoholrelated pancreatitis was defined as the daily intake of more than 60-80 g of ethanol for more than 5 years. In order to evaluate pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, fecal pancreatic elastase was determined in 20 g of feces in all patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia, and values<200 μg/g were considered as exocrine insufficiency.[11]

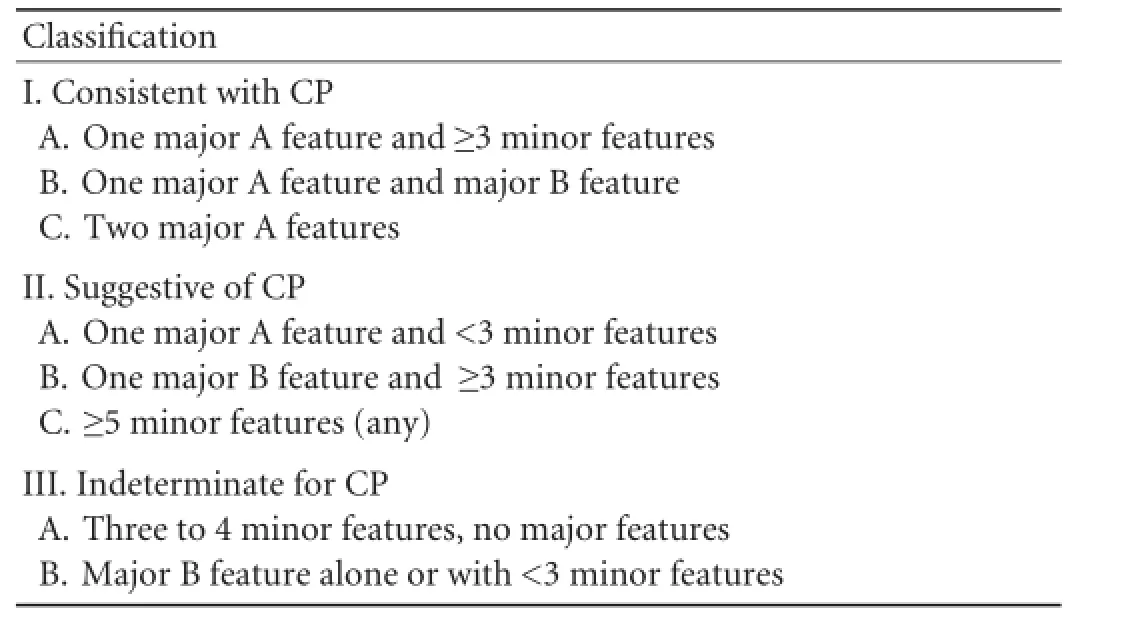

All patients were examined with EUS (Pentax EG-3830UT Linear Endoscopic Ultrasound and Hitachi EUB-525 F Ultrasound, Tokyo, Japan) before the endoscopic therapeutic procedures by the same endosonographer (Senturk H) and were classified as consistent, suggestive and indeterminate for CP, according to the Rosemont classification.[12]This classification includes major A criteria (hyperechoic foci with shadowing and main pancreatic duct calculi), major B criterion (lobularity with honeycombing) and minor criteria (lobularity without honeycombing, hyperechoic foci without shadowing, cyst, stranding, irregular main pancreatic duct contour, dilated side branches, main pancreatic duct dilatation and hyperechoic main pancreatic duct margin) (Table 1).

SPSS 13.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. All data are expressed as mean, with the SD of the mean calculated when appropriate. Nonequally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median values with their minimum and maximum ranges. For comparison of data in different groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed and the results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and with P value. A P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.Rosemont classification

Results

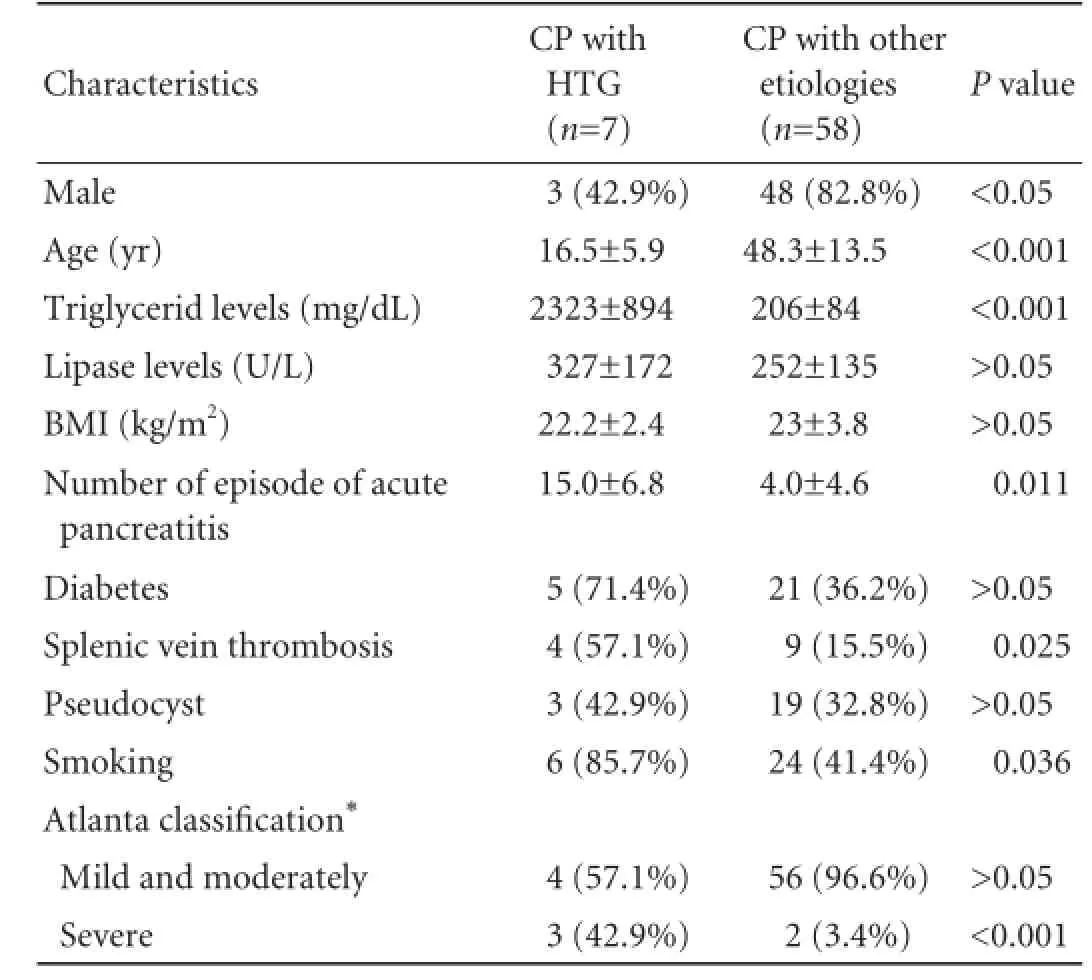

A total of 65 patients with CP treated in our department between 2007 and 2011 were evaluated. CP due to alcohol was seen in 24 of patients without HTG and CP due to pancreas divisum in 1, and no etiological factor in 33. In 7 CP patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia, no other etiological factor was present. The mean followup period of patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia was 55 months (range 22-94). The mean level of serum triglyceride was 2323±894 mg/dL. The mean age of patients in the HTG and non-HTG groups at the diagnosis was 16.5±5.9 and 48.3±13.5 years, respectively (P<0.001). Of the 7 patients with HTG, 6 were smokers (P=0.036). Splenic vein thrombosis was found in 4 of the 7 patients, but none of these patients had gastrointestinal bleeding. The percentage of patients with severe acute pancreatitis according to the Atlanta classification was higher in the HTG group (P<0.001). The risk of severe acute pancreatitis was 21 times higher in HTG-induced CP patients than in other CP patients (Table 2). Theresults of comparative analysis of the patients with and without HTG are shown in Table 2.

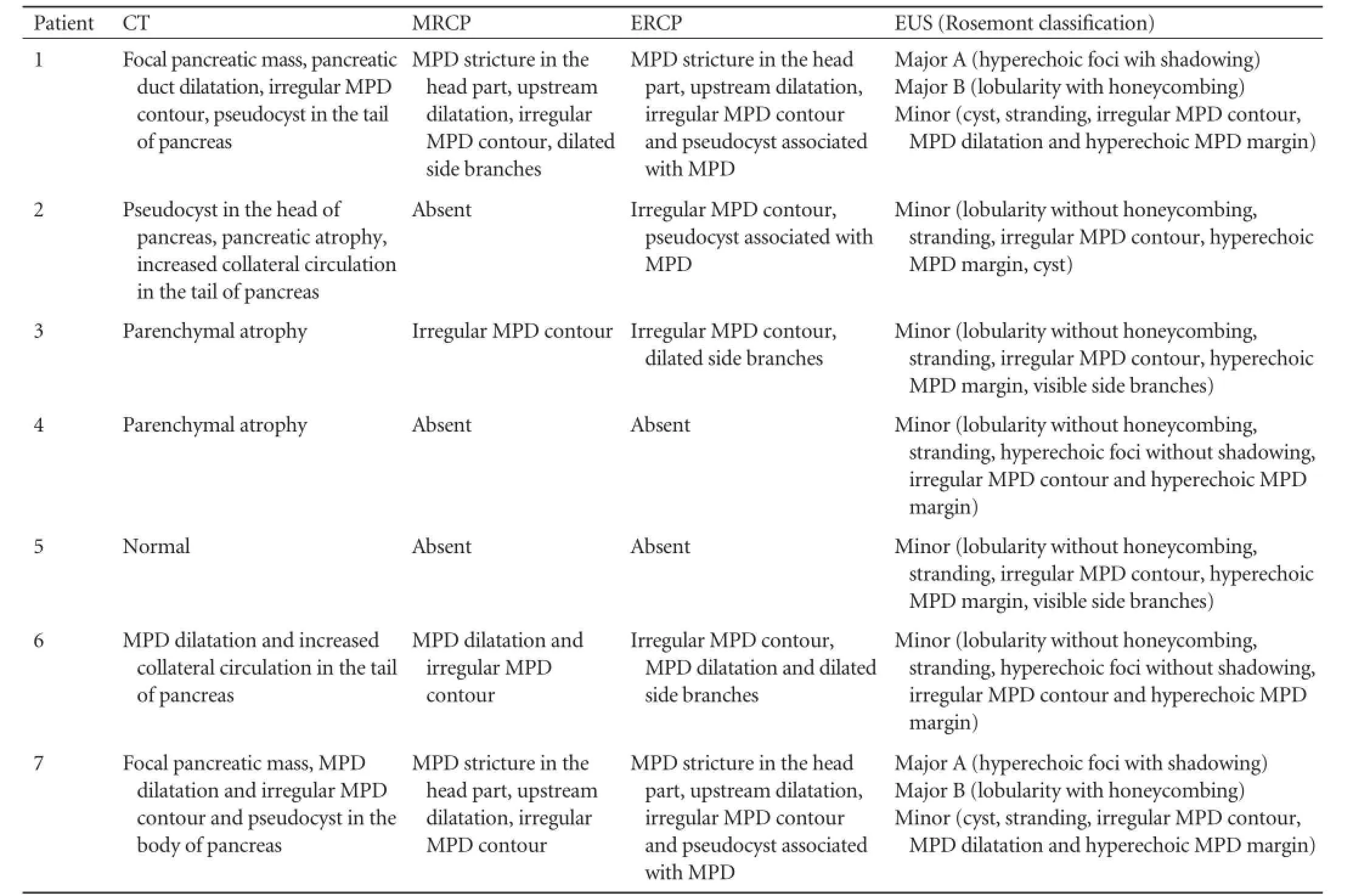

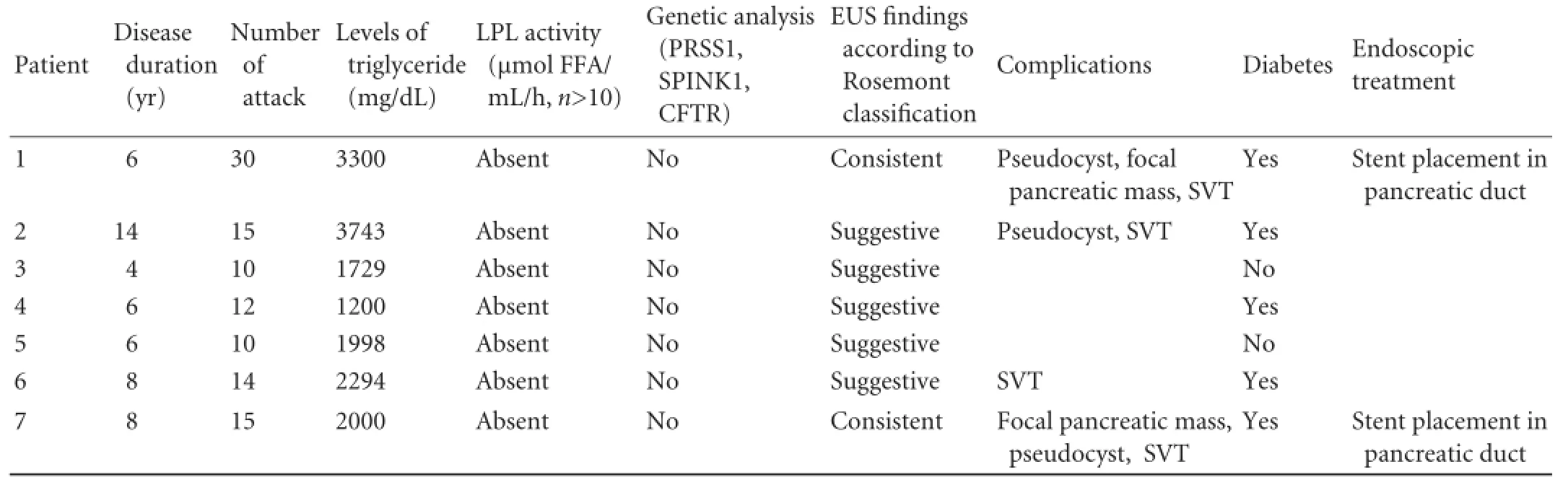

In logistic regression analysis of variables including age, gender, and smoking status, only younger age was proved to be an independent predictor of CP caused by HTG. Among the 7 patients with CP caused by HTG, 5 diabetic patients were subjected to insulin treatment. Steatorrhea was present in one patient who had also a decreased level of fecal elastase. But this decreased level was also observed in another patient who had no steatorrhea. CT and MRCP examination of the abdomen demonstrated dilated pancreatic duct with irregular borders in 3 patients. Moreover, pancreatic pseudocyst was detected in three patients (in the head region in 2 and in the body in 1). EUS findings according to the Rosemont classification were consistent and suggestive in 2 and 5 of the 7 patients, respectively. EUS revealed dilatation and irregular borders of the main pancreatic duct in 3 patients. ERCP was performed in 5 patients, with distinct upstream dilatation of the Wirsung duct in 2 patients. Pseudocysts communicating with theWirsung duct were found in 3 patients. Radiologic features of CP patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia are shown in Table 3. In 2 patients with a mass in the head of the pancreas, EUS-fine needle aspiration (EUSFNA) was performed (22 gauge Wilson-Cook Echotip needle). Histopathological findings were compatible with acute necrosis, fibrotic stroma and chronic inflammation. In the palliative treatment of pain in 2 patients with obstruction of the Wirsung duct (patient number 1 and 7), 5F plastic pancreatic stents were placed in the main pancreatic duct. During the followup, the patients had only two relapses of abdominal pain or acute pancreatitis. Features of patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia with CP are shown in Table 4.

Table 2.Comparison of CP patients with and without HTG at the time of CP diagnosis

Table 3.Radiologic features of CP with type 1 hyperlipidemia at the time of CP diagnosis

Table 4.Features of CP with type 1 hyperlipidemia

Discussion

Type 1 hyperlipidemia as a genetic disease is commonly seen in the infantile period. Pancreatitis due to type 1 hyperlipidemia runs a severe course disorder that may be potentially life-threatening.[13]Acute pancreatitis due to any cause is an emergency and necessitates an urgent intervention. However, in patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia, further management of hyperlipidemia to prevent future attacks is recommended.[3,14]Therapeutic options in type 1 hyperlipidemia are primarily based on diet and lipid lowering drugs. Thus, a diet very low in fat and rapidly absorbable carbohydrates is recommended. Alcohol must be avoided. Nicotinic acid, fibrates, and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids have been successfully used.[15]Repeated plasmapheresis as a prophylactic measure has also been used in patients with recurrent pancreatitis induced by severe primary HTG that was unresponsive to medical and dietary interventions.[16]

Currently, it is accepted that recurrent acute pancreatitis may, and in most cases will, lead to CP.[17]We observed that the recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis develop in younger patients with HTG, and that the number and severity of attacks were higher than in patients without HTG. We suggest that severe recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis may lead to permanent damage to pancreatic tissue. On the other hand, tobacco use is an accelerating factor in the progression of disease among alcoholic CP patients, and is an independent risk factor for the development of CP.[18]Tobacco use in patients with HTG may be a precipitating factor for recurrent pancreatitis attacks and the progression of disease.

In our series, 4 patients had splenic vein thrombosis among the HTG group. The high rate of splenic vein thrombosis in the HTG group may be due to an increased number of acute recurrent pancreatitis episodes and/or to endothelial dysfunction, as well as to local complications (like pseudocyst or fibrosis).

EUS is a routine procedure in our clinic in patients with CP at the time of the diagnosis, even if other radiological modalities already suggest this diagnosis. In case of malignancy suspicion or any local complication of CP we either perform EUS-FNA or EUS-guided therapeutic procedures if possible. A few studies have attempted to evaluate the EUS findings extensively in CP patients.[19-21]One study comparing EUS with surgical pathology revealed that three or more EUS criteria provided the best balance of sensitivity (83%) and specificity (80%), whereas five or more was more specific, but less sensitive.[20]Another study found that four or more criteria were the best threshold value.[21]The Rosemont classification uses parenchymal and ductal criteria which are divided into major and minor features. On this basis, the findings are classified as"consistent with CP", "suggestive of CP", "indeterminate for CP", or "normal" (Table 1). In our study, we detected EUS findings of CP in 7 patients with type 1 hyperlipidemia consistent in 2 and suggestive in 5 according to the Rosemont classification. In these two patients who were classified as consistent according to the Rosemont classification, both of them had one major A (hyperechoic foci with shadowing) and one major B (lobularity with honeycombing) criteria and four minor criteria (pseudocyst, stranding, irregularity in the main pancreatic duct and pancreatic duct dilatation). In patients who were suggestive according to the Rosemont classification, 5 or more minor criteria were reported. Five patients who were classified as "suggestive" according to the Rosemont classification were diagnosed with CP as they had other supporting features like fecal elastase levels (patient number 4 and 5), positive ERCP findings (patient number 2, 3 and 6) or diabetes (patient number 2, 4 and 6). In summary, Rosemont findings in this group were supported by the presence of at least one other feature of CP to ensure the diagnosis.

Endoscopic treatment is effective in a short-term follow-up of patients suffering from obstructive-type pain.[22,23]In our study, only two pancreatitis attacks were seen after stent placement in 2 patients (patient number 1 and 7) during the follow-up period. The development of CP in HTG patients is a controversial issue. In one study, no case of CP was found in a series of acute pancreatitis associated with HTG, followed up for a mean duration of 42 months.[24]In this study, only one patient had type 1 hyperlipidemia. This patient had 38 episodes of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting and was hospitalized for four times until the diagnosis was made. The patient had no relapse of abdominal pain or attack of pancreatitis after treatment of hyperlipidemia. The inability to demonstrate CP may be due to a shorter duration of follow-up compared to our study or to the absence of EUS evaluation.

In another cohort study,[25]there was no case of CP associated with HTG. The patients enrolled in this cohort study had type 4 and 5 hyperlipidemia and there was no long-term follow-up. Other small case series of HTG progressing with calcification and leading to exocrine or endocrine deficiency are present in the literature.[26-28]Histologically verified CP was also shown in one of the patients in one of these studies.[28]Histological examination is rarely performed in the evaluation of CP. In our study, two patients were diagnosed with CP which was confirmed histopathologically.

This study has several weaknesses. Limitations include the small sample size, the retrospective nature and the high prevalence of type 1 hyperlipidemia in our CP series. Because it is hard to manage recurrent pancreatitis patients associated with HTG, these patients are often referred to our department from other medical centers throughout the country. This explains the relatively high prevalence of type 1 hyperlipidemia in our CP series.

In conclusion, we reported 7 patients with CP who had no other etiological factor except type 1 hyperlipidemia. We suggest that familial chylomicronemia could be an etiological factor for CP in some patients. It manifests at a younger age and the course of the disease might be severe.

Contributors:SG proposed the study. SG and SH performed research and wrote the first draft. SG, EY, HI, CE, BS and SV collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Pezzilli R. Etiology of chronic pancreatitis: has it changed in the last decade? World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4737-4740.

2 M?ssner J, Keim V. Pancreatic enzyme therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;108:578-582.

3 Fortson MR, Freedman SN, Webster PD 3rd. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:2134-2139.

4 Anderson F, Thomson SR, Clarke DL, Buccimazza I. Dyslipidaemic pancreatitis clinical assessment and analysis of disease severity and outcomes. Pancreatology 2009;9:252-257.

5 Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998;27:551-567.

6 Brunzell JD, Bierman EL. Chylomicronemia syndrome. Interaction of genetic and acquired hypertriglyceridemia. Med Clin North Am 1982;66:455-468.

7 Lankisch PG, Breuer N, Bruns A, Weber-Dany B, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Natural history of acute pancreatitis: a long-term population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104:2797-2806.

8 Nilsson-Ehle P, Ekman R. Rapid simple and specific assays for lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase. Artery 1977;3:194-209.

9 French Consensus Conference on Acute Pancreatitis: Conclusions and Recommendations. Paris, France, 25-26 January 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:S1-13.

10 Bradley EL 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg 1993;128:586-590.

11 Girish BN, Rajesh G, Vaidyanathan K, Balakrishnan V. Fecal elastase1 and acid steatocrit estimation in chronic pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol 2009;28:201-205.

12 Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, Romagnuolo J, Wiersema M, Brugge W, et al. EUS-based criteria for the diagnosisof chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:1251-1261.

13 Valbonesi M, Occhini D, Frisoni R, Malfanti L, Capra C, Gualandi F. Cyclosporin-induced hypertriglyceridemia with prompt response to plasma exchange therapy. J Clin Apher 1991;6:158-160.

14 Gan SI, Edwards AL, Symonds CJ, Beck PL. Hypertriglyceridemiainduced pancreatitis: A case-based review. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:7197-7202.

15 Chait A, Brunzell JD. Chylomicronemia syndrome. Adv Intern Med 1992;37:249-273.

16 Piolot A, Nadler F, Cavallero E, Coquard JL, Jacotot B. Prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: value of regular plasmapheresis. Pancreas 1996;13:96-99.

17 Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology 2001;120:682-707.

18 Yadav D, Hawes RH, Brand RE, Anderson MA, Money ME, Banks PA, et al. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and the risk of recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1035-1045.

19 Chong AK, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Adams DB, Lewin DN, Romagnuolo J. Diagnostic performance of EUS for chronic pancreatitis: a comparison with histopathology. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:808-814.

20 Varadarajulu S, Eltoum I, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA. Histopathologic correlates of noncalcific chronic pancreatitis by EUS: a prospective tissue characterization study. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66:501-509.

21 Chong AK, Romagnuolo J. Gender-related changes in the pancreas detected by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:475.

22 Gabbrielli A, PandolfiM, Mutignani M, Spada C, Perri V, Petruzziello L, et al. Efficacy of main pancreatic-duct endoscopic drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis, continuous pain, and dilated duct. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61:576-581.

23 Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Le Moine O, Delhaye M, Vandermeeren A, Baize M, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic drainage in chronic pancreatitis associated with ductal stones: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;43:547-555.

24 Athyros VG, Giouleme OI, Nikolaidis NL, Vasiliadis TV, Bouloukos VI, Kontopoulos AG, et al. Long-term followup of patients with acute hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;34:472-475.

25 Lloret Linares C, Pelletier AL, Czernichow S, Vergnaud AC, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, Levy P, et al. Acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 129 patients referred for severe hypertriglyceridemia. Pancreas 2008;37:13-22.

26 Krauss RM, Levy AG. Subclinical chronic pancreatitis in type I hyperlipoproteinemia. Am J Med 1977;62:144-149.

27 Hacken JB, Moccia RM. Calcific pancreatitis in a patient with type 5 hyperlipoproteinemia. Gastrointest Radiol 1979;4:143-146.

28 Truninger K, Schmid PA, Hoffmann MM, Bertschinger P, Ammann RW. Recurrent acute and chronic pancreatitis in two brothers with familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Pancreas 2006;32:215-219.

Received December 11, 2012

Accepted after revision June 3, 2013

Author Affiliations: Division of Gastroenterology, Istanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul 34100, Turkey (Sisman G, Erzin Y, Hatemi I and Caglar E); Division of Gastroenterology, ?i?li Etfal Education and Research Hospital, Istanbul 34365, Turkey (Boga S); Division of Gastroenterology, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore 1830 E, USA (Singh V); Division of Gastroenterology, Bezmialem School of Medicine, Istanbul 34100, Turkey (Senturk H)

Yusuf Erzin, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Istanbul University Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul 34100, Turkey (Tel: 90-532-2655008; Fax: 90-212-2525057; Email: dryusuferzin@yahoo. com)

? 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60033-3

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Improved anterior hepatic transection for isolated hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate

- Instrumental detection of cystic duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Pancreatic fistula after central pancreatectomy: case series and review of the literature

- Multi-visceral resection of locally advanced extra-pancreatic carcinoma

- Pancreatic head cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis

- FBW7 increases chemosensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through suppression of epithelialmesenchymal transition