Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and liver fbrosis

Haifeng Kan, Long Chen, Zhiyun Yang, Shixiang Zhu

Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and liver fbrosis

Haifeng Kan, Long Chen, Zhiyun Yang, Shixiang Zhu

Objective:The current study discusses the relationship between sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) and liver fbrosis by determining the level of plasma hyaluronic acid (HA), procollagen III (PIII), collagen IV (IVC), and laminin (LN) in OSAHS patients and non-OSAHS patients with obesity and normal body weight.

Methods:The patients who underwent polysomnographic (PSG) examinations in the outpatient and inpatient departments of our hospital between December 2010 and June 2013 were selected. The patients were divided into two groups based on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI; OSAHS and non-OSAHS patients), and both groups were further divided based on obesity and normal body weight based on the body mass index (BMI). Sleep breathing indicators, including BMI, AHI, LSaO2, and MSaO2, were measured in all patients. All of the patients had their blood drawn on the morning after the day of the PSG examination, and the samples were sent to the biochemical laboratory of our hospital for determination of the levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN.

Results:Among the obese and normoweight patients, the levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in OSAHS patients were higher than the non-OSAHS patients (Pvalue <0.05). Amongst the OSAHS and non-OSAHS patients, the levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in the obese patients were also higher than the non-obese patients (Pvalue <0.05). The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in the obese OSAHS patients were higher than the remaining three groups (Pvalue <0.05). The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had positive correlations with the AHI and BMI (r=0.701, 0.523, 0.639, and 0.421, respectively,P<0.05; and r=0.565, 0.441, 0.475, and 0.401, respectively,P<0.05), and negative correlations with the LSaO2and MSaO2in OSAHS patients (r=—0.432, —0.394, —0.403, and—0.267, respectively,P<0.05; and r=—0.591, —0.517, —0.533, and —0.484, respectively,P<0.05).

Conclusion:The levels of plasma HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in OSAHS patients were related to OSAHS. OSAHS might lead to liver fbrosis.

Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS), Liver fbrosis, Hyaluronic acid (HA), Procollagen III (PIII), Collagen IV (IVC), Laminin (LN)

Introduction

The main symptom of obstructive sleep apneahypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is recurrent upper airway collapse during sleep, which causes snoring, frequent apnea and hypopnea, recurrent nocturnal hyoxemia and hypercapnia, and disordered sleep structure. OSAHS can involve multiple systems and cause damage to multiple organs, and it constitutes an independent risk factor to cardiovascular andcerebrovascular diseases, which has thus drawn wide attention. More and more evidence has shown that in addition to damage to the cardiocerebral vascular system, OSAHS also damages the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital, endocrine, and musculoskeletal systems. The number of domestic and international studies investigating the impact of OSAHS on the liver is limited, and most of the studies have focused on changes in liver enzymograms. We have therefore conducted a preliminary investigation involving the relationship between OSAHS and liver fbrosis as evidenced by changes in HA, PIII, IVC, and LN.

Subjects and methods

Subjects of study

Fifty-two patients (45 males and 7 females; age range, 19—69 years; average age, 40.9±11.6 years) with OSAHS [1] were recruited from the outpatient and inpatient departments between December 2010 and June 2013. The patients were divided into 2 groups based on BMI (BMI≥28 kg/m2[n=27] and BMI<24 kg/m2[n=25]). The obesity criteria of theGuidelines for Prevention and Control of Overweight and Obesity in Chinese Adults,published by the Disease Control Department of National Ministry of Health in 2002, were followed [2]. In addition, 30 obesity patients without OSAHS (26 males and 4 females; age range, 22—64 years; average age, 39.2±9.4 years) based on PSG examinations in the outpatient and inpatient departments during the same study period were collected. Thirty patients (26 males and 4 females; age range, 24—63 years; average age, 38.5±10.3 years) were recruited for the normal control group. All of the patients were thoroughly questioned about their medical histories and biochemical testing was performed to exclude specifc diseases that can cause fatty liver, such as respiratory and circulatory system diseases, metabolic diseases, viral hepatitis, drug-induced hepatitis, hepatolenticular degeneration, and autoimmune liver diseases. None of the patients had histories of alcohol consumption or the amount of alcohol consumed was <140 and <70 g/w for males and females, respectively, without a history of parenteral nutrition. In addition, all of the patients signed informed consent.

Methods

Human parametric measurements: The height (m) and weight (kg) were measured to calculate the BMI (kg/m2).

PSG: All subjects underwent PSG monitoring for at least 7 h while sleeping to record the AHI, LSaO2, and MSaO2.

Determination of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN: All patients had been subjected to abrosia for 12 hour overnight. Three milliliters of blood was drawn from the antecubital vein while fasting between 06:15 and 07:00 the next morning, and the samples were sent to the biochemical laboratory of our hospital for determination of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN levels.

Statistical analysis

Results

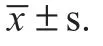

Basic information has been listed in Table 1. Among all groups tested, age had no statistical signifcance after one-way analysis of variance (P>0.05). Gender had no statistical signifcance on χ2testing (P>0.05).

Based on BMI, it was shown that among obese and normoweight patients, the levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN were higher than the non-OSAHS patients (Pvalue <0.05). Based upon AHI, it was shown that the levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in the obese patients were higher than the nonobese patients (P<0.05). The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN were higher in the obese OSAHS patients than the other 3 groups (P<0.05).

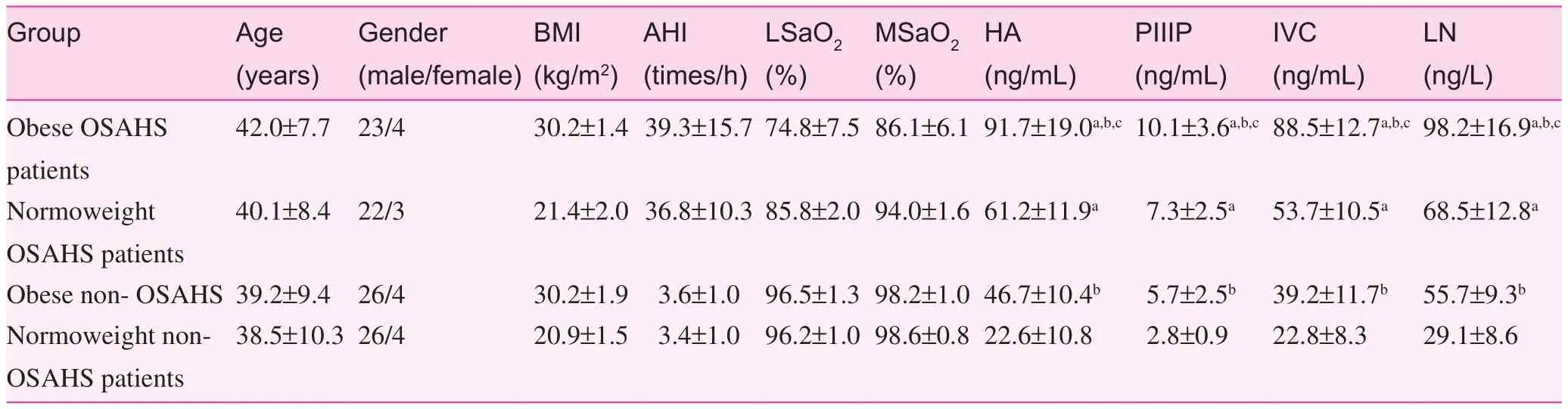

Results of correlation analysis between the levels of HA, PIII, IVC and LN in OSAHS patients, BMI and sleep monitoring indicators are listed in Table 2.

The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had a positive correlation with the AHI of OSAHS patients (r=0.701, 0.523, 0.639, and 0.421, respectively,P<0.05).

The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had a positive correlation with BMI of OSAHS patients (r=0.565, 0.441, 0.475, and 0.401, respectively,P<0.05).

The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had a negative correlation with the LSaO2of OSAHS patients (r=—0.432, —0.394,—0.403, and —0.267, respectively,P<0.05).

Table 1. Basic information of patients in all groups

Table 2. Correlation analysis (correlation coeffcient) between serum fbrosis markers of OSAHS patients and BMI and sleep monitoring indicators

The levels of HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had a negative correlation with the MSaO2of OSAHS patients (r=—0.591, —0.517,—0.533, and —0.484, respectively,P<0.05).

Discussion

OSAHS is closely associated with metabolic syndrome (MS). Intermittent hypoxia, hypercapnia, sleep deprivation, and awakening play a vital role in the occurrence and development of MS. Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and obesity exacerbate OSAHS, thus creating a vicious circle. Due to such a close association between the OSAHS and MS, the co-existence of OSAHS and MS z-syndrome has been suggested [3].

The liver is the most important organ involved in patients with glucose and lipid metabolic disorders. Insulin resistance and lipid metabolic disorders can lead to hepatic cell lipidosis and form simple fatty liver, which further causes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) under the infuence of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation-associated damage. In the event of persistent NASH, the patient will develop infammation and necrosis, which is converted to fatty liver fbrosis [4, 5]. The occurrence of liver fbrosis relies on excitation of hepatic stellate cells. Hyperglycemia can promote proliferation of hepatic stellate cells and collagen synthesis. Insulin resistance can stimulate the amount of free fatty acids (FFA) that fow into the liver. An abundance of FFA peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a (PPAR-a) increases the concentration of peroxide, gives rise to the generation of oxygen radicals, and induces the release of infammatory mediators. Various infammatory mediators activate the hepatic stellate cells, which further proliferate and are activated to develop into muscle fber cells. Many muscle fber cells can synthesize extra-cellular matrix (ECM) protein, and the substantial deposition of ECM eventually leads to the formation of liver fbrosis.

The laboratory diagnoses of liver fbrosis proposed in theDiagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for Combination of Chinese Traditional and Western Medicine of Liver Fibrosis[6] andConsensus of Liver Fibrosis Diagnosis and TherapeuticEffect Evaluation[7] include histopathologic, imaging, and serum fbrosis marker examinations. Histopathologic examinations provide the most important information with which to support a diagnosis, measure the extent of infammation and fbrosis, and ascertain the drug therapeutic effect; however, a liver biopsy requires a thick needle penetration, which falls into the category of a traumatic and invasive procedure. Such experiments cannot be conducted for ethical reasons, therefore we selected non-traumatic examination indicators. Nontraumatic examinations consist of imaging and serum fbrosis marker examinations. The serum fbrosis marker examination refects liver infammation and fbrosis.

Plasma HA, PIII, IVC, and IN are all markers of serum fbrosis. Joint detection of the serum fbrosis indicators is of importance in establishing a diagnosis [6, 7].

The levels of serum HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in the obese patients were higher than the non-obese patients amongst OSAHS and non-OSAHS patients (Pvalue <0.05), and the levels of serum HA, PIII, IVC, and LN had a positive correlation with BMI.

Whether obese or normoweight, the levels of serum HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in OSAHS patients were higher than non-OSAHS patients, and the levels of serum HA, PIII, IVC, and LN in OSAHS patients had a positive correlation with AHI and a negative correlation with the lowest blood oxygen saturation and the average blood oxygen saturation, which indicated that OSAHS might cause liver fbrosis. Based on a histologic analysis, Kallwitz et al. [8] reported that obese OSAHS patients were more likely to develop fatty liver hepatitis and liver fbrosis when compared with obese patients. Among patients with obesity, more severe OSAHS was associated with more severe fatty liver hepatitis and liver fbrosis [9]. Tatsumi et al. [10] reported in a non-obese OSAHS patients-focused study, that in spite of a similar incidence of simple fatty liver between the OSAHS and non-OSAHS patients, the level of PIIIP, which refects fbrosis, was associated with the average blood oxygen saturation. Tatsumi et al. [10] believes that the average blood oxygen saturation is a risk factor for fatty liver hepatitis, and OSAHS is one of the mechanisms underlying liver fbrosis. Our research results showed that the lowest blood oxygen saturation and the average blood oxygen saturation were closely associated with liver fbrosis. Animal experiments have confrmed that chronic intermittent hypoxia is a risk factor [11, 12] for changing simple fatty liver into fatty liver hepatitis. In addition, the “twohit hypothesis” suggests that intermittent hyoxemia in OSAHS patients can further prompt transformation from fatty liver to fatty liver hepatitis, which develops into liver fbrosis [13, 14].

In summary, OSAHS patients might develop liver damage or even liver fbrosis due to insulin resistance [15], nocturnal intermittent hypoxia, and oxidative stress. The explicit mechanism for liver fbrosis caused by OSAHS is not clear. In obese and non-obese patients with OSAHS, determination of the levels of serum HA, PIII, IVC, and LN can help identify damage early to facilitate the timely treatment of primary diseases and to reduce the incidence of liver fbrosis and to improve the prognosis of OSAHS patients. In addition, we plan to conduct experiments with color Doppler ultrasound and CT to further prove the relationship between OSAHS and liver fbrosis.

Confict of interest

The authors declare no confict of interest.

1. Sleep Respiratory Disturbance Group of Respiratory Medicine Branch of Chinese Medical Association. Diagnosis and Treatment Guideline of OSAHS (2011 revised edition). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis 2012;35:9—12.

2. Disease Control Department of Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in chinese adults. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2006. pp. 3—4.

3. Wilox I, Mc Namara SG, Collins FL, Grunstein RR, Sullivan CE.“Syndrome Z”: the interaction of sleep apnea, vascular risk factors and heart disease. Thorax 1998;53 Suppl 3:S25—8.

4. Donati G, Stagni B, Piscaglia F, Venturoli N, Morselli-Labate AM, Rasciti L, et al. Increased prevalence of fatty liver in arterial hypertensive patients with normal liver enzymes: role of insulin resistance. Gut 2004;53:1020—3.

5. Diem AM. Fatty liver, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome. Gut 2004;539:923—4.

6. Specialized Committee of Hepatopathy under Chinese Association of the Integration of Traditional and Western Medicine. Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines for Combination of Chinese Traditional and Western Medicine of Liver Fibrosis. Chin J Hepatol 2006;11:866—70.

7. Liver Fibrosis Group under Chinese Hepatopathy Association. Consensus of Liver Fibrosis Diagnosis and Therapeutic Effect Evaluation. Chin J Hepatol 2002;10:327—8.

8. Kallwitz ER, Herdegen J, Madura J, Jakate S, Cotler SJ. Liver enzymes and histology in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41:918—21.

9. Mishra P, Nugent C, Afendy A, Bai C, Bhatia P, Afendy M, et al. Apnoeic-hypopnoeic episodes during obstructive sleep apnoea are associated with histological nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int 2008;28:1080—6.

10. Tatsumi K, Saibara T. Effects of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome on hepatic steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res 2005;33:100—4.

11. Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Vivero A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia predisposes to liver injury. Hepatology 2007;45:1007—13.

12. Savransky V, Bevans S, Nanayakkara A, Li J, Smith PL, Torbenson MS, et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia causes hepatitis in a mouse model of diet-induced fatty liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;293:G871—7.

13. Day CP, James OF, Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology 1998;114:842—5.

14. Day CP, Saksena S. Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis: defnitions and pathogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17 Suppl 3:S377—84.

15. Zhang XL. OSAHS and Insulin Resistance. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis 2008;31:644—6.

Rugao People’s Hospital, Nantong, Jiangsu 226500, China

Haifeng Kan

Rugao People’s Hospital, Nantong, Jiangsu 226500, China

E-mail: 43203323@163.com

22 May 2014;

Accepted 10 August 2014

Family Medicine and Community Health2014年3期

Family Medicine and Community Health2014年3期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Preparation of a questionnaire for disease knowledge-attitudepractice awareness of patients with remitted schizophrenia based on a structural equation model

- Association between esophageal cancer in middle-aged and elderly patients and body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio

- Role of fractional fow reserve in guiding intervention for borderline coronary lesions

- Relationship between fbroblast growth factor 21 and thyroid stimulating hormone in healthy subjects without components of metabolic syndrome

- Family Medicine and Community Health

- Family Medicine and Community Health COCHRANE UPDATES & NICE GUIDELINES