Recent Development on Zero-Phosphate Spray Dried Detergent Powders Incorporated with Palm C16 Methyl Ester Sulfonates

Parthiban Siwayanan

Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Malaysia

Ting Young Kang

Pentamoden Sdn. Bhd., Kampung Baru Sungai Buloh, Malaysia

Ramlan Aziz, Nooh Abu Bakar, Shreeshivadasan Chelliapan

Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Yahya Petra, Malaysia

Introduction

Detergent industry is a highly competitive market and detergent powders have the largest market share worldwide compared to other detergent formats. Laundry detergent powders are extensively used around the globe and they typically contain surfactants, builders, bleaching agents,enzymes and fillers[1]in various proportions. Among these ingredients, surfactants have been of paramount importance in the detergents innovation due to their exceptional cleaning chemistry.[2]Surfactants can be defined as compounds that lower the surface tension of water and possess the wetting, emulsifying and dispersing properties that enable the removal of stain from fabrics.[3]Surfactants also can be broadly classified as being anionic, cationic, non-ionic, and amphoteric or zwitterionic by the charge on the surface active component.[4]In the production of laundry detergent powders, anionic surfactants are used in greater volume than others because of their ease of use and low cost.[5]The raw materials used for the production of anionic surfactants are primarily derived from two sources, petrochemicals and oleochemicals.[6]About 75% of anionic surfactants (excluding soaps) used globally are based on synthetic raw materials.[7]Petrochemical based linear alkyl benzene sulphonate (LABS)has been the dominant workhorse of the detergent industry back in the 20th century[8]and Malaysia being one of the importers of this surfactant.[9]

Since the beginning of this millennium, green and ecofriendly became two big buzzwords in the marketing of detergents.[10]This development poses a great challenge to the formulators to find ways in increasing the green oleochemical based surfactants[11]and reducing harmful detergent ingredients such as phosphates[12]in the detergent formulations. Under these circumstances, there has been a paradigm shift where some detergent formulators turned their attention into detergent products that address the cost, environment and sustainability.[2]As oleochemistry provides the solution for sustainable future, more studies on detergent formulation have been carried out towards this direction. However, the challenge for today’s detergent still lies in providing high performance with low cost of production.[13]This challenge has provided an enormous opportunity for methyl ester sulphonate (MES) to emerge into limelight after many decades in the experimental research. MES is an anionic surfactant, which produced via sulphonation of oleochemical feedstock such as methyl esters(ME). These ME can be derived from natural oils such as palm oil, coconut oil and soybean oil. MES is well known to possess outstanding characteristics in terms of detergency,water hardness tolerance, rapid biodegradability and low production cost.[14]It has the potential to substitute LABS and other oleochemical based anionic surfactants such as fatty alcohol sulfate (FAS) and fatty alcohol ether sulfate (FAES).[15]

The initial research on MES was carried out back in the early 1950s by the United States Department of Agriculture(USDA)[16,17]but only known as a class of surfactant in the 1980s.[18]In the initial stage of development, MES has been associated with several disadvantages mainly on its poor solubility, tendency to hydrolyze, longer processing time,irritancy, dark colour and also due to the presence of skin sensitized products. These negative properties of MES were back then created a fear factor for the detergent industry to scale-up the technology into large-scale production. However,with continuous research and good manufacturing practice,these technical issues were solved by several MES technology providers. As a result, the technology for producing excellent quality MES became commercially available in the early nineties.[19]However, due to lack of ME[20]and its subsequent MES, dawdling progress has been seen on the development of MES based laundry detergent powders.

The escalating prices of petrochemical feedstock in the beginning of 2000s has enabled MES to grasp the second wave of interest among the detergent producers. The interest was driven by the progress made in the research and development towards saturated palm C16 and palm stearin (C16/C18) MES.These surfactants possess high detergency to that of other commercial surfactants including the lower MES homologs(C12 and C14). The ME for the production of C16 and C16/C18 based MES are obtained from biodiesel production and through palm stearin esterification respectively. Due to the availability of palm stearin, majority of the research efforts are centered towards the C16/C18 based MES derived from this raw material. Saturated C16ME, which produced as byproduct upon removal of unsaturated C18ME, only came into limelight when the detergent producers in China and Southeast Asia spurred their interest to study the utilization of C16MES in the detergent formulations. C16MES derived from C16ME was found to have the edge over LABS in the aspects of green,performance, production cost and sustainability. C16MES also has great potential not only as the sole surfactant but also as cosurfactant in the production of laundry detergent powders.[21]

In terms of performance, MES derived from natural oils has all the advantages to outperform LABS. However,the primary challenge concerning C16MES still lies in the formulation and production process of low-density detergent powders (LDDP). In contrast to LABS, MES could not be applied directly into the spray drying process for the production of LDDP without sacrificing the detergency and other significant properties.[22]MES in general has been reported as suitable for non-tower agglomeration process,[23]which yields high-density detergent powders (HDDP) with bulk densities ranging between 0.55 to 0.75 kg/L and higher.The spray tower process, which normally used to produce LDDP with bulk densities ranging from 0.25 to 0.45 kg/L,[24]on the contrary was found to be unsuitable for MES. In the developing countries, LDDP are highly preferred by consumers[25]due to its low cost and high volume over weight ratio.

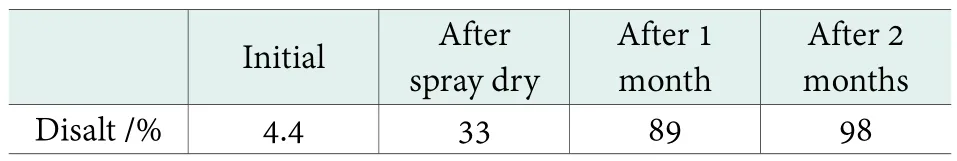

Previous studies have revealed that MES will undergo partial hydrolysis (decomposition of ester group) under spray drying conditions and degrades into a less active byproduct — disalt.[26]Disalt possesses inferior detergency properties and will result in deterioration of the detergency performance.[27]This hydrolysis process normally occurs when MES is exposed for a long time at a pH of below 3 or above 10[28,29]and also at high spray drying temperature.[30]Table 1 indicates the effect of hydrolysis on the disalt content over 2 months of storage period.[29]

Table 1. Hydrolysis of MES after spray drying process

It has been reported that binary anionic surfactants containing MES and LABS could provide a solution to the MES hydrolysis problem in the spray drying process.[31]Binary MES and LABS also may provide synergistic effect in the laundry detergents where their combined detergency could be higher than their respective individual surfactant.Besides detergency, particle characteristics such as particle size, size distribution and surface morphology are also essential in the development of LLDP particularly for studying the dissolution rate, volume over mass ratio and flowability properties. Due to insufficient scientific data on this subject matter, a systematic and thorough study mainly on different formulations of the binary anionic surfactant system is required to determine its suitability as raw material for the production of LDDP in the spray drying process.

In this study, binary surfactants of C16MES and acidic linear alkyl benzene sulfonic acid (LABSA) were used to address the technical disadvantage of MES in the spray drying process. The optimum concentration of the detergent slurry was determined and the cleaning performance in terms of initial detergency, detergency stability over 9 months storage, foaming ability, and wetting power of the resulting spray-dried detergent powders (SDDP) was evaluated. The selected SDDP produced from the ideal PFD formulation was further subjected to biodegradability and eco-toxicity analyes.The effect of different ratios of C16MES/LABSA have also been studied on particle characteristics such as particle size, particle size distribution, surface morphology,volume to mass ratio and flowability.

Materials & Methods

Materials

C16MES (87.4% active matter) of desired disalt content was obtained in powder form from KL-Kepong Oleomas Sdn. Bhd., Selangor, Malaysia. LABSA, NaOH (32%),carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), Na-aluminosilicate (zeolite 4A), citric acid monohydrate, sodium sulfate anhydrous,sodium silicate and sodium metasilicate pentahydrate,which necessary for PFD formulations, were bought from the commercial sources. Since C16MES is sensitive towards alkaline ingredients, acidic LABSA with the average molecular weight of 318 was used instead of LABS. Due to hazardous contribution to the process of eutrophication,sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP) was not included in the PFD formulation.[12,32]STPP is generally added in the manufacture of detergents to enhance the cleaning efficiency. The post-mix ingredients including enzyme,optical brightner, colorant, anti-redoposition, bleaching agents and perfume were not included as well in the PFD formulation.

Pilot scale production of SDDP

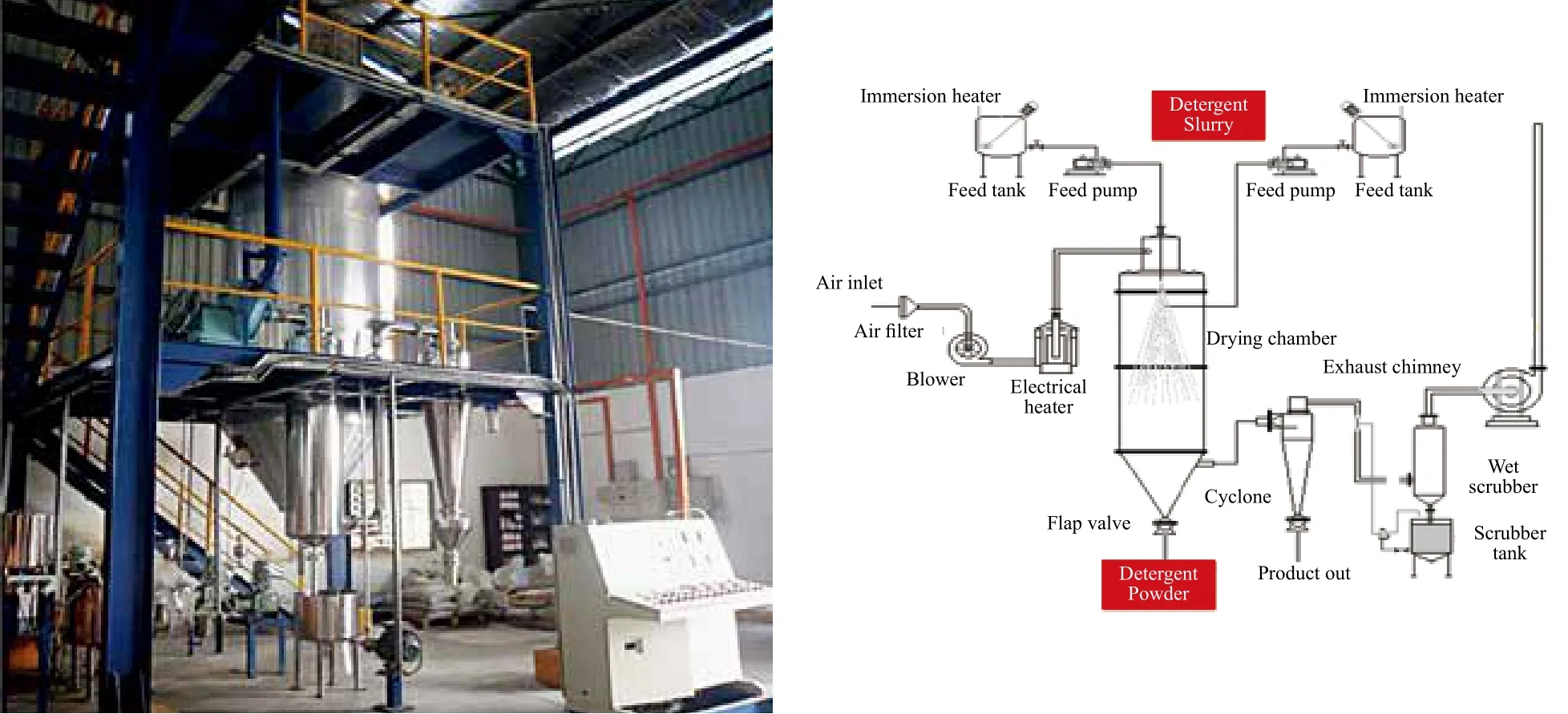

A customized pilot scale spray dryer (PSD), as shown in Figure 1, which purchased from Acmefil Engineering Systems Pvt. Ltd., India, was used in a co-current operation to convert the fine spray droplets of detergent slurry into solid and dried particles of the detergent powder. Six different PFD formulations consisting of C16MES/LABSA (0 : 100,20 : 80, 40 : 60, 60 : 40, 80 : 20 and 100 : 0) were used in the PSD for the production of SDDP. Three major steps are involved in the SDDP production. The first step involves the preparation of detergent slurry from the formulation ingredients using two feed tanks equipped with electrical heaters and agitators. Hot deionized water was used to dissolve the C16MES. Other ingredients such as LABSA,CMC, zeolite A4, Na-metasilicate pentahydrate, and sodium sulfate anhydrous were subsequently added into the C16MES solution with continued agitation for 15 minutes at 150 rpm to achieve a homogeneous detergent slurry. Some of the PFD formulations were observed to have elevated viscosities and appropriate amount of deionized water was added into such formulations to optimize the flowability of the slurry.

Figure 1. Pilot spray dryer

The second step involves the atomization of the slurry,which takes place using two-fluid nozzle. The droplets upon sprayed in the spray chamber, will be dried with the hot air. In the final step, the dried solid particles with the desired level of moisture content were collected at the base compartment of PSD. The moisture content of the final SDDP particles was controlled by changing the rate of input feed. An integrated system of the cyclone separator and wet scrubbing was used to recover the product particles escaping from the spray dryer. Clean air was vented to the atmosphere using an exhaust blower through a chimney. The SDDP particles were cooled to ambient temperature and characterized for cleaning performance and evaluation of environmental properties.

Detergent slurry analysis – slurry concentration and pH

The total mass of the constituent ingredients (except water) was divided by the overall mass of the materials to determine the percentage of slurry concentration used in the spray dryer. The pH strips were used to measure the pH of 0.1 % solution of the detergent slurry.

Detergent cleaning performance

Detergency

The cleaning performance of SDDP in terms of detergency was determined using three types of artificially soiled fabrics: JB01 (carbon soil), JB02 (protein soil), and JB03 (sebum soil). The reflectance (whiteness) of the fabrics was measured before washing with a whiteness meter at 457 nm. Four strips of each of the fabric types(6 cm×6 cm dimensions) were washed in water at a temperature of 30 ?C for 20 minutes with a wash load stirring at 120 rpm. Precalculated amount of the SDDP samples were added for the cleaning purpose. After washing, fabric strips were rinsed and dried followed by the reflectance measurement. Equation 1 was used to determine the detergency performance.

Where RAWand RBWrepresent average reflectance for detergent samples after and before washing respectively, whileanddenote average reflectance for the reference detergent after and before washing respectively. All these detergency tests were conducted as per Standard Code of China,GB/T 13174-2008 in Lonkey Industrial Chemical Co. Ltd.

Foaming

The foaming test was conducted in line with the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) in-house method. A 0.1% solution for each of the prepared detergent samples was prepared and put in a measuring cylinder. The solution was agitated up and down 30 times by using a standard plunger and the height of foam was determined immediately after agitation and 5 minutes after the agitation was stopped. The change of foam height was reported as a measure of the foaming stability.

Wetting

This test was also performed by the in-house method developed by MPOB. For this purpose, a 2 cm × 2 cm piece of unsoiled cotton was conditioned at 20% relative humidity for one day and it was dropped on the surface of the 0.1%solution prepared with the SDDP samples. The time was recorded from the moment cotton piece touched the surface of the solution until it was completely immersed in it.

Evaluation of environmental properties of SDDP

Biodegradability

The biodegradability test was conducted only for the selected SDDP sample (from the ideal PFD formulation)prepared in the spray dryer. The biodegradability tests were accomplished in a mineral medium with a concentration of approximately 2~5 mg/L. A 2 mg/L solution of the selected SDDP was inoculated with inoculums (a mixed bacterial population) obtained from the secondary effluent of a treatment plant that treats the domestic sewage. The samples were kept in fully closed bottles in the dark at a constant temperature. This closed bottle test followed the standard OECD 301D and is in line with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (EOCD)Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals.[33]The analysis of dissolved oxygen (DO) was carried out at 22~25 ?C for a period of 28 days. The percentage of theoretical oxygen demand (THOD) was determined by the amount of oxygen consumed by the microorganisms during the biodegradation process followed by correction for oxygen uptake by the blank inoculums run in parallel. The dissolved oxygen from the SDDP sample was measured every four days to construct the biodegradation curve. It is generally known that a substance is fully biodegradable if it is biodegraded greater than or equal to 60% within 28 days of the test period.

Eco-toxicity

The eco-toxicity test was performed following the standard method of OECD 203, the Fish Acute Toxicity Test in accordance with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (EOCD) Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals.[34]The test was carried out by exposing the Tilapia nilotica fish to water dissolved with the selected SDDP sample (from the ideal PFD formulation) in different concentrations. In the first step,the range of concentration of the selected SDDP sample was identified by exposing the fish for a period of 24 hours to get the logarithmic series of concentrations. The concentration range was specified by the observation of zero to 100% mortalities and this range was used to conduct the next definitive test. In this step, the fish were exposed to water dissolved with selected SDDP sample at different concentrations (in geometric series) of the detergent for a period of 96 hours. The geometric mean of the highest concentration causing no mortality and the lowest concentration causing 100% mortality were calculated and expressed as LC50. LC50is the concentration of detergent at which 50% of the fish died during the test period. The LC50rating in accordance with the scheme by the United States Fish and Wildlife Services was used as a reference to rate the eco-toxicity[35,36]of the ideal PFD formulation.

Particle characterization of SDDP

Bulk density

The bulk density of the SDDP samples was measured by filling a graduated glass cylinder by the known mass of the detergent and noting down the untapped volume occupied. The mass of sample was divided by the untapped volume to calculate the bulk density.

Particle size characteristics

To analyze the particle size distribution of the SDDP particles, laser particle size analyzer (Model CILAS 1190 Dry; CILAS, France) with an operating vacuum pressure of 1,000 hPa was used. The particle characteristics of the SDDP were studied by using the particle diameters at cumulative volume percentage of 10% (D10), 50%(D50), 60% (D60) and 90% (D90) based on the particle size distribution.

Surface morphology

The surface morphology of the SDDP particles was carried out using EVO LS 10, Carl Zeiss variable pressure scanning electron microscope. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was operated under vacuum at 15 kV and the micrographs were taken at a magnification of 450.

Tapped density & flowability

Tapped density can be measured by dividing the mass of SDDP sample by the tapped volume. In order to calculate tapped density, known mass of SDDP sample was put in a glass cylinder and tapped 30 times. After tapping, the final volume was noted to calculate the tapped density.

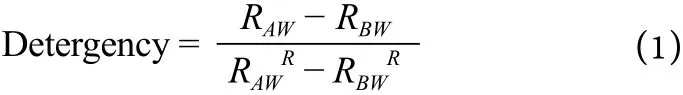

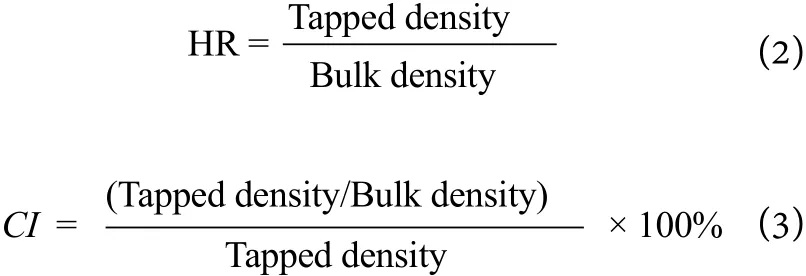

The flowability of powders is generally presented in terms of Hausner ratio (HR) and Carr’s index (CI).An HR of less than 1.15 indicates good flowability,between 1.15 and 1.25 indicates that improvement can be made using glidant, whereas above 1.25 indicates poor flowability.[37]Similarly, flowability is believed to be excellent for a CI range of 5~15%, good for CI of 12~16%, fair for CI range of 18~21% but a CI greater than 23% represents poor flowability.[38]The HR and CI were calculated by using equations 2 and 3 as follows.

Results & discussion

Detergent slurry analysis – slurry concentration and pH

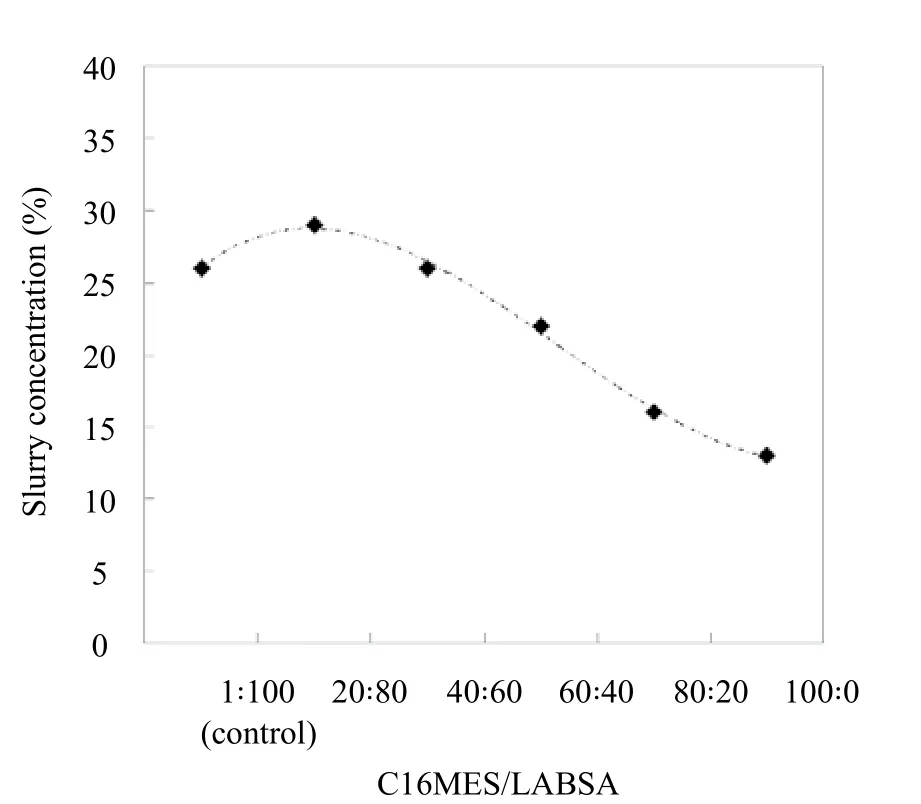

Figure 2. Detergent slurry concentration at different C16MES/LABSA ratios

While using the spray dryers, it is important to know the optimum concentration of the slurry because it does not only affect the flowability but also the droplet size of the spray. The recommended optimum concentration of the slurry to be used in a PSD, according to the PSD supplier, is between 25%and 30%. Figure 2 shows the concentration profile of the PFD slurry for different formulations of C16MES/LABSA. The formulation of C16MES/LABSA with a proportion of 0 : 100 is used as a control.

It can be observed from Figure 2 that the concentration for C16MES/LABSA formulations with 20:80 and 40 : 60 proportions are 29% and 26% respectively which are within the recommended concentration values. However, the concentration of the SDDP slurry for 60 : 40, 80 : 20, and 100 : 0 is lower than that of 20 : 80 and 40 : 60 formulations.This is because, during the preparation of the slurries for different formulations, it was observed that the viscosities of the 60 : 40, 80 : 20, and 100 : 0 formulations increased significantly due to the typical behavior of C16MES. The augmented viscosity offers an impediment to the smooth flow of the slurry from feed tanks to the two-fluid nozzle.It affects the droplet size of the spray[39]and hence the characteristics of the resultant detergent powder as well. To address this issue, calculated amount of de-ionized water was added to these formulations to reduce the viscosities to an appropriate level to facilitate the flowability. Hence, the slurry concentrations of the C16MES/LABSA formulations for 60 : 40, 80 : 20, and 100 : 0 are lower.

Detergent cleaning performance

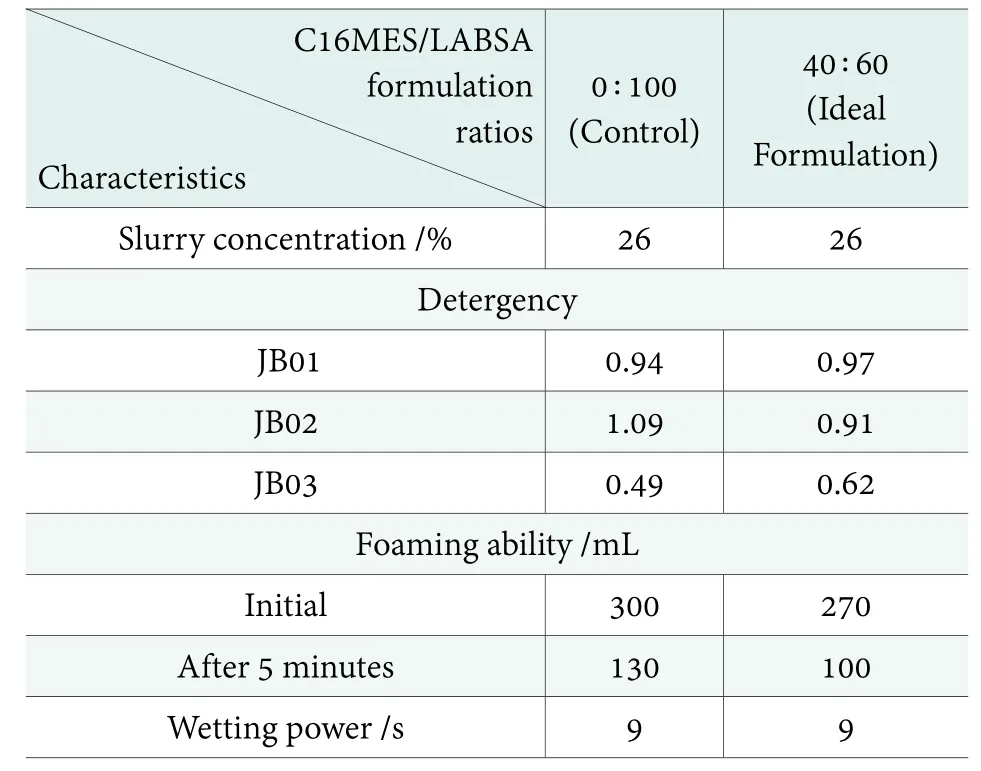

The cleaning performance of a detergent is a function of detergency, foaming ability and wetting power. During the evaluation of these parameters, C16MES/LABSA with a proportion of 0 : 100 was used as a control.

Detergency

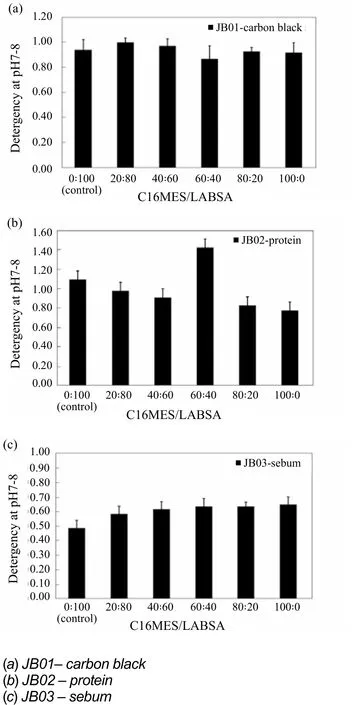

The evaluation of detergency is important to investigate the ability of the detergents to remove the stains from the fabrics. The detergency results are shown in Figure 3 in which the detergency profiles of different formulations of C16MES/LABSA detergent samples for three different fabrics; JB01,JB02, and JB03 are shown. It can be seen in Figure 3(a) that the detergency of all the C16MES/LABSA formulations tested on JB01 fabric is between 0.87 and 1.0 range, which is almost in accordance to the detergency of the control formulation (0.84).A decreasing trend is observed in the detergency of C16MES/LABSA formulations tested on JB02 fabric in Figure 3(b) except for the 60 : 40 formulation, which has detergency significantly higher than the control. In Figure 3(c), a logarithmic increase in the detergency of all the C16MES/LABSA formulations can be observed for JB03 fabric which means that the detergency can be enhanced significantly by the increase in C16MES concentration in the formulation.

Figure 3. Detergency of pilot scale PFD formulations over different ratios of C16MES/LABSA

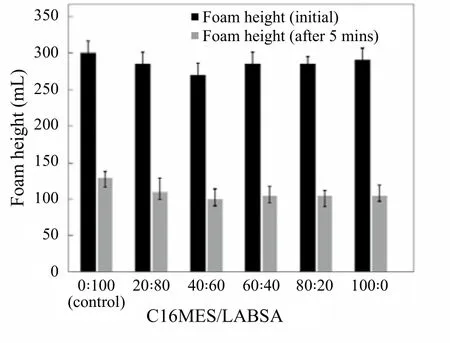

Figure 4. Foaming ability of pilot scale PFD formulations over different ratios of C16MES/LABSA

Foaming

When detergents are stirred, they produce a certain degree of foam which is basically the mass of bubbles governed primarily by the surface tension of the detergent liquid. The foaming of the detergent can be reported in terms of the foam height it produces as a result of agitation.Figure 4 represents the foam heights (both, initial and after 5 minutes) for control (0 : 100) and all the C16MES/LABSA formulations. The initial foam height for the control appears to be 300 mL while the initial foam height for all the C16MES/LABSA formulations ranges between 270~290 mL. This shows that the foaming results of all the formulations are comparable with the control. The foam height for the control after 5 minutes resulted in 130 mL,whereas, for rest of the C16MES/LABSA formulation, it ranges between 105~110 mL. This shows that the foam heights are not only consistent within the C16MES/LABSA formulations but also comparable to the control.

Wetting Power

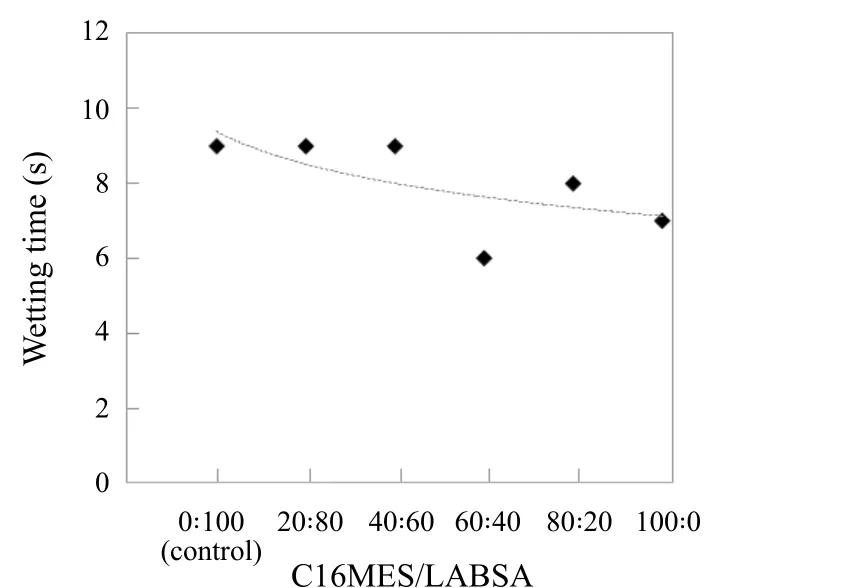

The time taken for the fabrics to get completely wet by the detergent solution is reported as a measure of the wetting power of the detergent and is seen as an important property of the detergent with respect to its cleaning performance.Figure 5 shows wetting time of the fabrics in the detergent solutions formed by different formulations of C16MES/LABSA and the control. A wetting time of 9 s was observed for 20 : 80, 40 : 60 formulations of C16MES/LABSA and the control. Hence, the wetting time for these C16MES/LABSA formulations is comparable with the wetting time of the control. A significant decrease in the wetting time can be observed for other C16MES/LABSA formulations with lowest wetting time being 6 s for 60 : 40 of C16MES/LABSA.This infers that the increase in C16MES content results in the superior wetting properties of the detergent. This is because the MES is generally known to have better wetting characteristics as compared to LABS.

Figure 5. Wetting power of pilot scale PFD formulations over different ratios of C16MES/LABSA

Identification of the ideal PFD formulation produced in PSD

The ideal PFD formulation was needed to be identified in order to study its environmental impacts such as biodegradability and eco-toxicity. For this purpose, the characteristics of different C16MES/LABSA formulations were compared with those of the control. With this background, a comparative analysis shows that the 20 : 80 and 40 : 60 of C16MES/LABSA formulations have comparable properties of slurry concentration and cleaning performance with the control. However, C16MES/LABSA with 40 : 60 was selected as the ideal formulation because of its higher C16MES content. A summary of the comparison of different characteristics of 40 : 60 C16MES/LABSA formulation and the control is given in Table 2. The ideal formulation is further subjected to biodegradability and eco-toxicity test to evaluate its environmental acceptability.

Table 2. Characteristics of ideal pilot scale PFD formulation in comparison with the contro

Evaluation of environmental properties of SDDP

Biodegradability

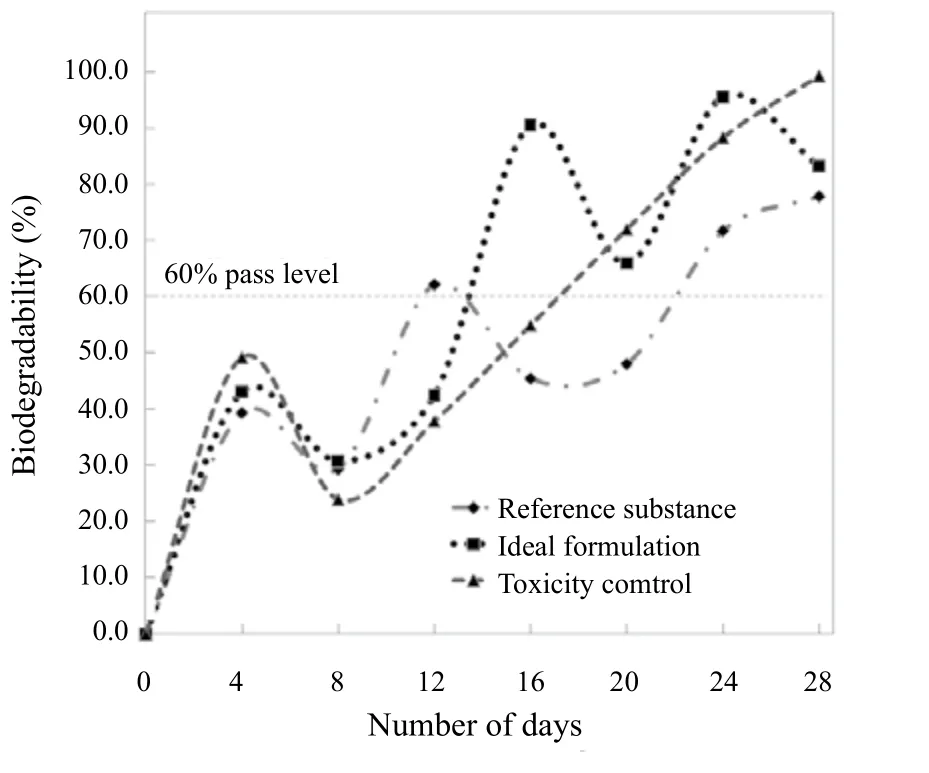

The biodegradability of detergents is important because the non or less biodegradable substances can pose water pollution and disturb the marine ecosystem once this polluted water flows into the lakes or rivers or the ocean. Biodegradation is the process of decomposition of substances by the enzymatic or microbial activity. Biodegradability evaluation is essential for assesign environmental risk and it is also required by the concerned environmental or legislative agencies.In Figure 6, the biodegradation curves for the ideal PFD formulation, the toxicity control and the reference substance are shown.

Figure 6. Biodegradability of ideal pilot scale PFD formulation

It can be observed that the biodegradability pass level of 60% for the ideal PFD formulation was achieved in 13 days and the maximum biodegradability of 95.6%was achieved in 24 days. The toxicity control, on the other hand, requires 20 days to reach the 60% pass level of biodegradability which indicates that the selected SDDP (from the ideal PFD formulation) meets the biodegradability standards and is not likely to pose any hazardous threat to the environment.

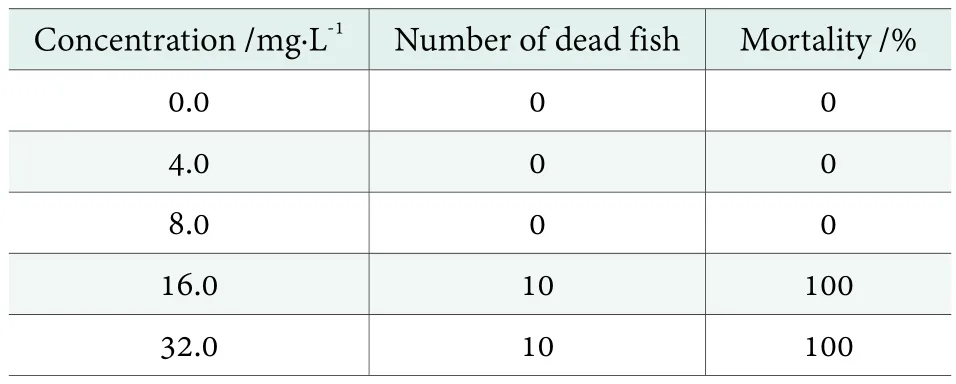

Eco-toxicity

This test is important with regard to the evaluation of the toxicity level that the detergent solutions can pose to the aquatic life through the wastewater pathways. The eco-toxicity test was carried out with the ideal pilot scale PFD formulation to evaluate the aquatic toxicity. The ecotoxicity results are presented in Table 3. The fish mortalities have been reported after an exposure of 96 hours. Based on these results, LC50of the ideal formulation was calculated as the geometric mean of the highest concentration that caused zero mortalities (8.0 mg/L) and the lowest concentration that caused 100% mortalities (16.0 mg/L). The LC50thus calculated for the ideal formulation was 11.3 mg/L which lies in the range of slightly toxic as per rating scheme of the U.S. The fish and Wildlife Services. Maurad et al.[40]reported that the LC50for the single surfactant (MES)based detergents was in the range of 5.66~8.0 mg/L which can be classified as moderately toxic. Although enormous quantities of the surfactants are being discharged into the waterways, they are not found to have serious threats to the aquatic environment.

Table 3. Fish mortalities after 96 h for SDDP resulted from ideal pilot scale PFD formulation

Particle characterization of SDDP

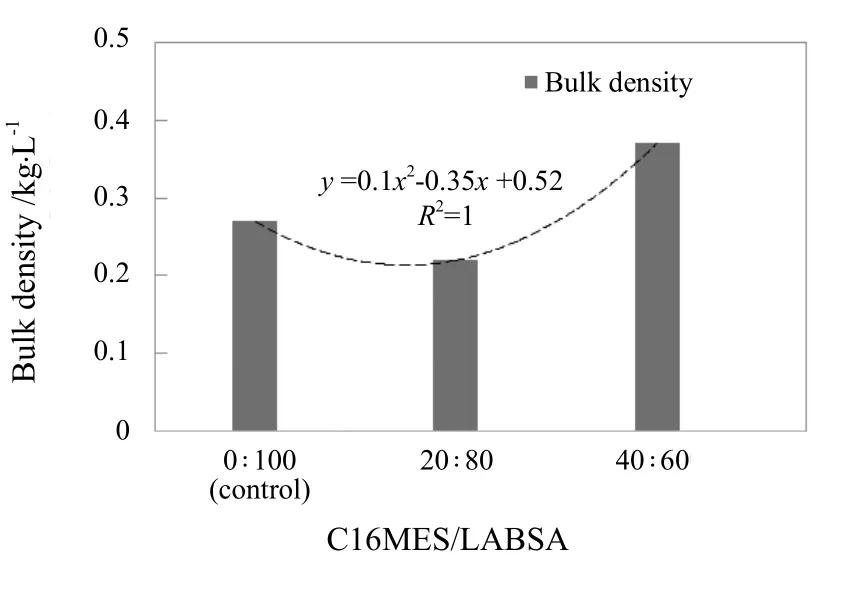

Bulk density

The bulk density (Db) for the control and three PFD formulations with different C16MES/LABSA ratios are plotted in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Effect of different C16MES/LABSA ratios on bulk density

The bulk density of the control and C16MES/LABSA formulations with the ratios of 20 : 80 and 40 : 60 were 0.27,0.22 and 0.37 kg/L respectively.

Particle size characteristics

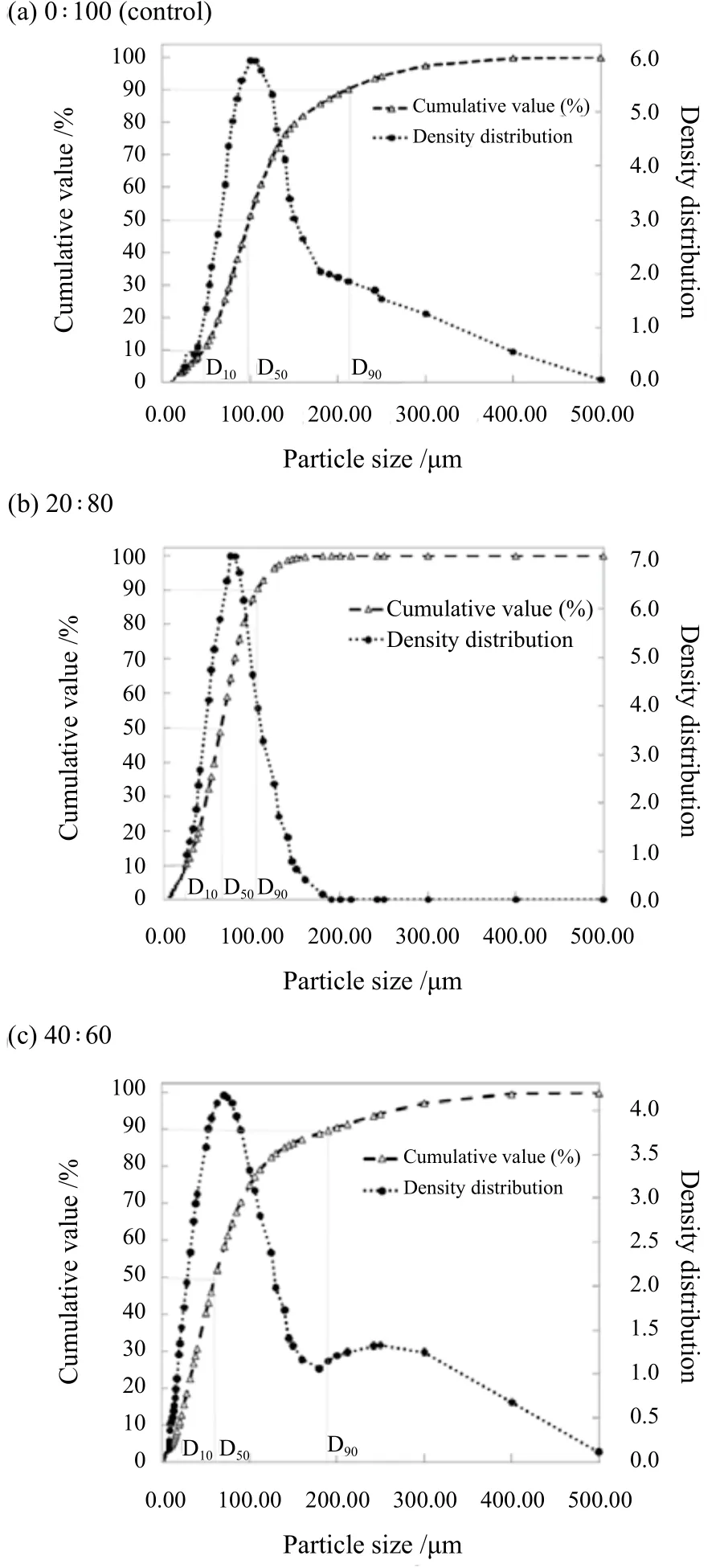

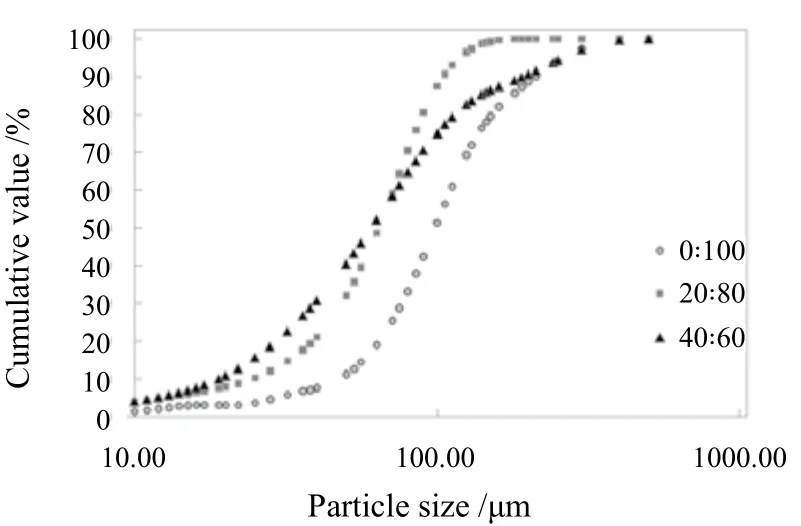

The influence of SDDP particles from different C16MES/LABSA formulations on the particle size characteristics such as particle size distribution (PSD), the coefficient of particle size uniformity (Pu) and spread of equivalent particle diameter (Sed)has been plotted and shown in Figure 8(a)(b)(c), Figure 9, and Figure 10 respectively. It can be observed in Figure 8 that the particle size distribution of the control and C16MES/LABSA in 20 : 80 and 60 : 40 ratios were skewed positively and three particle diameters (D10/D50/D90) were measured on the x-axis in order to define their characteristics. The D10/D50/D90for the control and C16MES/LABSA formulations are given in Table 4.The D10and D50were found to decrease with the increase of the C16MES content whereas D90increased with increase in the C16MES content.

Figure 8. Effect of different C16MES/LABSA formulations on particle size distribution for (a)0 : 100, (b) 20 : 80, and (c) 40 : 60 ratios

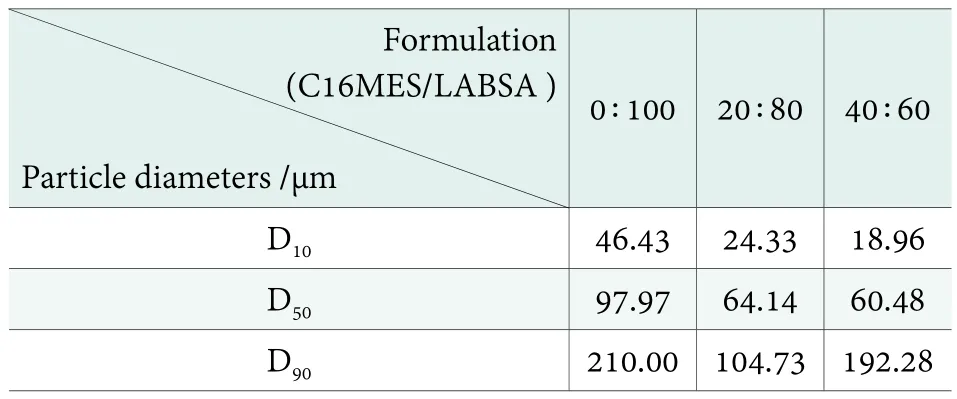

Table 4. Particle diameters for different C16MES/LABSA ratios at 10%, 50% and 90% cumulative volume distribution

The coefficient of particle size uniformity (Pu) directly affects the dissolution of detergent particles, higher the Pu,higher would be the dissolution. The Pu was calculated by dividing the D60over D10. The resulting D60/D10values of the control and SDDP particles of C16MES/LABSA formulations with 20 : 80 and 40 : 60 ratios are 2.38, 2.97, and 3.86 respectively such that the SDDP particles with 40 : 60 ratio of C16MES/LABSA have the highest D60/D10value as shown in Figure 9. A linear increase in the values of Pu can be observed in Figure 9 with an increase in the C16MES content. It infers that the dissolution quality of the 40 : 60 particles would be superior as compared to others. It was evident that as C16MES content increases, the Db and Pu also increase whereas the D10and D50, on the contrary, decrease.

Figure 9. Effect of different C16MES/LABSA ratios on particle size uniformity (Pu)

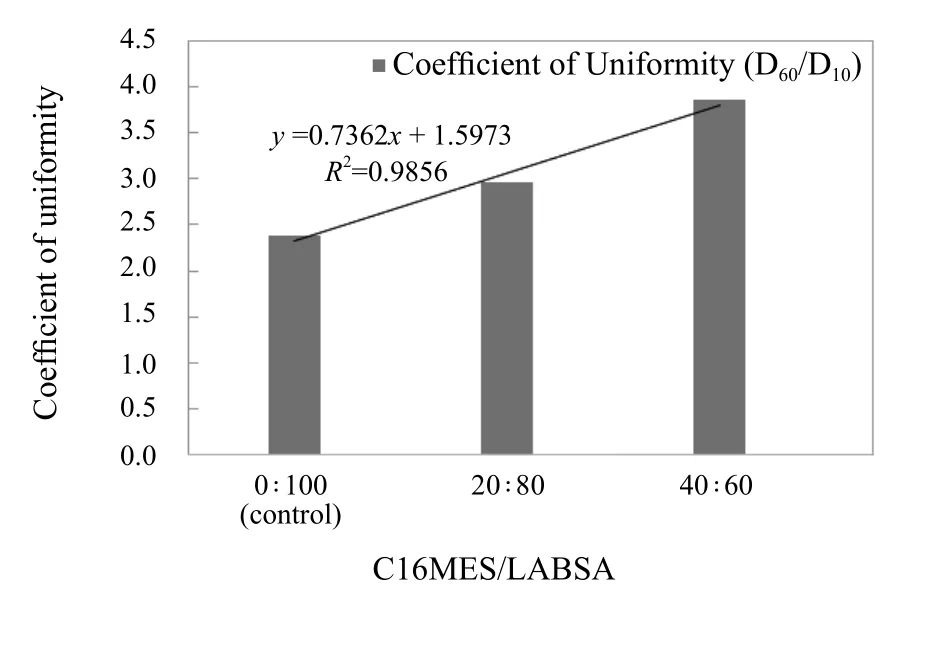

The equivalent particle diameter (Sed) was calculated by plotting cumulative volume percentage as the x-axis and log particle size as the y-axis as shown in Figure 10. The SDDP particles resulting from C16MES/LABSA formulations with 40 : 60 ratio was found to have the highest value of Sedwhich is indicative of the widest particle size distribution.However, the other two formulations resulted in narrow particle size distribution due to low equivalent particle diameter.

Figure 10. Effect of C16MES/LABSA ratios on spread of equivalent particle diameters (Sed)

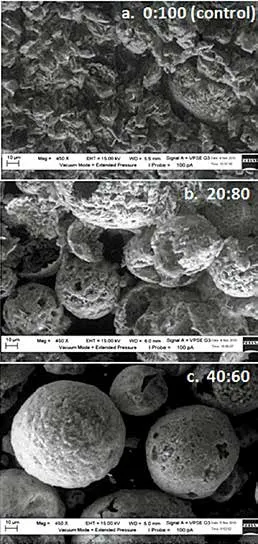

Surface Morphology

The surface morphology of the SDDP particles was carried out by the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).The micrographs of the particles from the control and different C16MES/LABSA formulations are shown in Figure 11. It can be seen in Figure 11(a) that the control particles have rough, irregular and disorganized surfaces.The SDDP particles with 20:80 ratio of C16MES/LABSA,the particles are observed to have hollow structures with distorted and rough surfaces as shown in Figure 11(b).

To the contrary, regular, organized, and stable spherical particles with smooth surfaces were can be observed in Figure 11(c) for particles of SDDP with 40 : 60 ratio of C16MES/LABSA formulation. It can be concluded that the surface characteristics of the SDDP particles can be improved significantly by the addition of C16MES content.

Figure 11. Effect of different C16MES/LABSA ratios; (a)0 : 100, (b) 20 : 80, and (c) 40 : 60 on surface morphology of SDDP particles

Tapped density & flowability

The tapped density (Dt) of the detergent particles is determined to evaluate the flowability characteristics.The Dt of SDDP particles resulting from the ideal PSD formulation was found to be 0.47 kg/L. The HR and CI SDDP particles were calculated based on the Dt value which came out to be 1.27% and 21.3% respectively.The calculated HR and CI values were slightly higher than the standard values required for free-flowing characteristics of the detergent powder. The HR value lower than 1.4 indicates that the SDDP particles are noncohesive. However, the hygroscopic nature of C16MES makes the SDDP particles vulnerable to be influenced by the moisture and, therefore, increases the inter-particle cohesiveness which offers a barricade to the free-flow of the particles. It is known that the development of liquid bridges between the hygroscopic particles gives rise to the strong inter-particle affinity resulting in the major setback to the flowability.[41]In order to enhance the flowability of the SDDP particles, the HR and CI values need to be reduced by the addition of glidants.

Conclusion

Previously, it was established that the process conditions of the spray dryer are not feasible for the MES surfactant based detergent formulations to manufacture LDDP. In this study, the production of binary C16MES/LABSA surfactant based SDDP and their characterization have revealed that C16MES can be successfully used in the spray drying process if an appropriate ratio of the binary C16MES/LABSA surfactant is employed at a neutral pH. The effective PFD formulation from this study can be effectively used for the production of SDDP without sacrificing the cleaning performance and environmental properties.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to offer their most profound gratitude to Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI) of Malaysia (Project reference:TF0208D024), Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia for their financial support of this project.

[1] Scott M. J.; Jones M. N. The Biodegradation of Surfactants in the Environment. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2000, 1508,235—251.

[2] Lafferty M. Detergent Chemistry Has Hit the Wall on Clean,So It’s Going Green. Inform 2010, 21, 465—528.

[3] Mukherjee A. K. Potential Application of Cyclic Lipopeptide Biosurfactants Produced by Bacillus Subtilis Strains in Laundry Detergent Formulations. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2007, 45, 330—345.

[4] Gecol H. The Basic Theory. In Farn R. J. (Ed.) Chemistry and Technology of Surfactants. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing 2006,24—25.

[5] Yangxin Y.; Zhao J.; Bayly A. E. Development of Surfactants and Builders in Detergent Formulations. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2008, 16, 517—527.

[6] Rust D.; Wildes S. Surfactants: A Market Opportunity Study Update-2009. http://soynewuses.org/wpcontent/uploads/pdf/Surfactants%20MOS%20-20Jan%02009.pdf. 2008. html(Accessed Feb 27).

[7] Pletnev M. Y. Chemistry of Surfactants. Amsterdam:Elsevier 2001.

[8] Chemsystems Perp Program: Linear Alkyl Benzene (LAB).www.chemsystems.com/about/cs/news/items/PERP%200708S 7_LAB.cfm.html (Accessed Jan 30).

[9] Ahmad S.; Kang Y. B.; Yusuf M. Basic Oleochemicals. In Basiron Y.; Jalani B. S.; K. W. Chan (Eds.) Advances in Oil Palm Research 2000, 1141—1194. Bandar Baru Bangi: Malaysian Palm Oil Board.

[10] Guala F.; Merlo E. An Eco-Friendly Surfactant for Laundry Detergents. Surfactants. Household and Personal Care Today 2013, 8(3), 19—21.

[11] De Guzman D. Guangzhou Surfactant Plant in China to Start up in Q2 2011. ICIS Chemical Business. www.icis.com/Articles/2010/10/9399640/guangzhou-surfactant-plant-inchina-to-start-up-in-q2-2011. 2010.html (Accessed Apr 19).

[12] Kohler J. Detergent Phosphates-An EU Policy Assessment.Journal of Business Chemistry 2006, 3(2), 15 — 30.

[13] ICIS Chemical Business Surfactant Manufacturers Look for Green but Cheap Petro-Alternatives.www.icis.com/Articles/2010/10/04/9396996/surfactant?manufacturers?look?for?green?but?cheap?petro-alternatives.html (Accessed Feb 2013).

[14] Martinez D.; Orozco G.; Rincon S.; Gil I. Simulation and Pre-Feasibility Analysis of the Production Process of A-methyl Ester Sulfonates (MES). Bioresource Technology 2010, 101,8762—8771.

[15] Ismail Z.; Ahmad S.; Sanusi J. Palm Based Surfactants Synergy in Soap Applications. MPOB Palm Oil Develoment 2002, 37, 9—13.

[16] Weil J. K.; Stirton A. J. Critical Micelle Concentrations of α-Sulfonated Fatty Acids and Their Esters. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1956, 60, 899—901.

[17] Weil J. K.; Bistline Jr.; R. G.; Stirton A. J. Sodium Salts of Alkyl α-Sulfopalmitates and Stearates. Journal of American Chemical Society 1953, 75, 4859—4860.

[18] Hibbs J. Anionic Surfactants. In Farn, R. J. (Ed.). Chemistry and Technology of Surfactants 2006, 106. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

[19] Satsuki T. Methyl Ester Sulfonates. In Karsa, D. R. (Ed). New Products and Applications in Surfactants Technology 1998,132—155. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

[20] Sun G. Methyl Ester Sulfonate Industry Poll. Methyl Ester Sulfonates. Inform: A Special Supplement—Biorenewable Resources 2006, 17(3), 4—6.

[21] Adami I. The Challenge of the Anionic Surfactant Industry.Inform: A Special Supplement—Biorenewable Resources 2008, 19(5), 10—11.

[22] Trivedi S.N. Methyl Ester Sulfonate Industry Poll. Methyl Ester Sulfonates. Inform: A Special Supplement—Biorenewable Resources 2006, 17(3), 4—6.

[23] Roberts D. W.; Giusti L.; Forcella A. Chemistry of Methyl Ester Sulfonates. Inform: A Special Supplement—Biorenewable Resources 2008, 19(5), 2—9.

[24] Jacobs J.; Jahnke U.; Jung D.; Oleffelmann R.; Adler W. U.S.Patent No. 5,149,455. www.uspto.gov. (Accessed Nov 30).

[25] Zoller U.; Sosis P. (Eds.). Handbook of Detergents—Part F:Production 2010. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

[26] Yamane I.; Miyawaki Y. Manufacturing Process of Alpha-Sulphomethyl Esters and Their Application to Detergents.Proceedings of 1989 PORIM International Palm Oil Development Congress 1989, 132—141.

[27] Huish P. D.; Jensen L. A.; Libe P. B. U.S. Patent No. 6,780,830.www.uspto.gov (Accessed Nov 29).

[28] Stein W.; Baumann H. α-Sulfonated Fatty Acids and Esters—Manufacturing Process, Properties and Applications. Journal of American Oil Chemists Society 1975, 52, 323—329.

[29] MacArthur B. W.; Brooks B.; Sheats W. B.; Foster N. C. Meeting the Challenge of Methyl Ester Sulfonation. Proceedings of the World Conference on Palm and Coconut Oils for the 21st Century 1999, 54—63.

[30] Satsuki T. Applications of MES in Detergents. Inform 1992, 3,1088—1108.

[31] Satsuki T. Methyl Ester Sulfonates. In Karsa, D. R. (Ed).New Products and Applications in Surfactants Technology.Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. 1998,132 — 155.

[32] Schindler D. W. Eutrophication and Recovery in Experimental Lakes—Implications for Lake Management. Science 1974, 184,897—899.

[33] OECD. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. Test No. 301:Ready Biodegradability, Vol 3. OECD Publishing, Paris, 1992,1—62.

[34] OECD. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. Test No. 203:Fish, Acute Toxicity Test, Vol 2. OECD Publishing, Paris, 1992,1—10.

[35] Drozd JC. Use of Sulfonated Methyl Esters in Household Cleaning Products. Proceedings World Conference on Oleochemicals into the 21st Century, 1990, 256—258.

[36] Johnson W. W.; Finley M/ T. Handbook of Acute Toxicity of Chemicals to Fish and Aquatic Invertebrates, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Research Publication, No. 137, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington DC. 1980.

[37] Hausner H. H. Friction Conditions in a Massive Metal Powder.International Journal of Powder Metallurgy 1967, 3, 7—13.

[38] Carr R. L. Classifying Flow Properties of Solids. Chem. Eng 1965, 72, 69-72.

[39] Patel RP; Patel MP; Suthar AM. Spray Drying Technology: An Overview. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 2009, 2,44—47.

[40] Maurad Z. A.; Ghazali R.; Siwayanan P.; Ismail Z.; Ahmad S. Alpha-Sulfonated Methyl Ester as an Active Ingredient in Palm-Based Powder Detergents. Journal of Surfactants and Detergents 2006, 9, 161—167.

[41] Abhaykumar Bodhmage. Correlation between Physical Properties and Flowability Indicators for Fine Powders. M.Sc.Thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Canada 2006.

China Detergent & Cosmetics2016年3期

China Detergent & Cosmetics2016年3期

- China Detergent & Cosmetics的其它文章

- Latest Research Progress of Alkyl Polyglycosides

- Impact of Air Pollution on Skin

- An Introduction to the Standardization of China Oral Care Products (Toothpaste) Industry

- Comparative Study on the Domestic and Abroad Patent Application about Liquid Laundry

- Standards on the Biodegradability of Surfactants in China

- Qualitative Identification of Propylene Tetramer Alkylbenzene Sulfonate and Alkylphenol Polyoxyethylene in Laundry Powders