Malignant transformation and treatment of cystic mixed germ cell tumor

Yapeng Zhao, Hongyu Duan, Qinghui Zhang,, Bingxin Shi, Hui Liang, Yuqi Zhang,(?)

?

Malignant transformation and treatment of cystic mixed germ cell tumor

Yapeng Zhao1, Hongyu Duan2, Qinghui Zhang1,2, Bingxin Shi1, Hui Liang2, Yuqi Zhang1,2(?)

1The Medical Center, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

2Department of Neurosurgery, Tsinghua University Yuquan Hospital, Beijing 100040, China

ARTICLE INFO

Received: 3 December 2015

Revised: 25 December 2015

Accepted: 31 December 2015

? The authors 2016. This article is published with open access at www.TNCjournal.com

KEYWORDS

germ cell tumor; surgery;

chemotherapy; prognosis

ABSTRACT

Objective: The authors report an extremely unusual presentation and management of a children pineal mixed germ cell tumor mainly composed of immature teratoma, aiming to summarize main theraptic points by literature review.

Methods: A cystic lesion located in the rear of third ventricle in a child was detected 3 years ago with no other therapy performed except for a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt. During the following 3 years, intermitted regular brain MRI demonstrated no evidence of lesion aggrandizement. However from 20 days before admission to our institute the patient began to present acutely with exacerbating clinical symptoms meanwhile brain MRI showed signs of abrupt revulsions of initial lesion without any incentive cause. Neurological examination revealed a significant rising of serum tumor marker level. Then surgical resection was performed immediately after admission which was followed by correlative two-course chemotherapy.

Results: Postoperative brain MRI demonstrated totally removing of the lesion in rear of third ventricle. Serum tumor marker level decreased remarkably after surgery and declined to normal level after two-course chemotherapy. No obvious neurological deficit occurred except for short-term memory difficulty which gradually recovered within two weeks. Soon after the second course chemotherapy the patient was currently asymptomatic and returned to school.

Conclusions: (1) To ensure definitive diagnosis and proper therapecutic protocols benefit from grasping clinical features of mixed germ cell tumor. (2) Overall preoperative investigation including serum tumor marker level is as critical as neurological imaging examination. (3) Surgical excision is confirmed to be the key modality of treatment. With the regarding of mixed germ cell tumor, never highlight total resection too much. (4) Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended as further intensive treatment to improve the prognosis of mix germ cell tumor.

Citation Zhao YP, Duan HY, Zhang QH, Shi BX, Liang H, Zhang YQ. Malignant transformation and treatment of cystic mixed germ cell tumor. Transl. Neurosci. Clin. 2016, 2(1): 25–30.

? Corresponding author: Yuqi Zhang, E-mail: yuqi9597@sina.com

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470048).

1 Case presentation

1.1 History

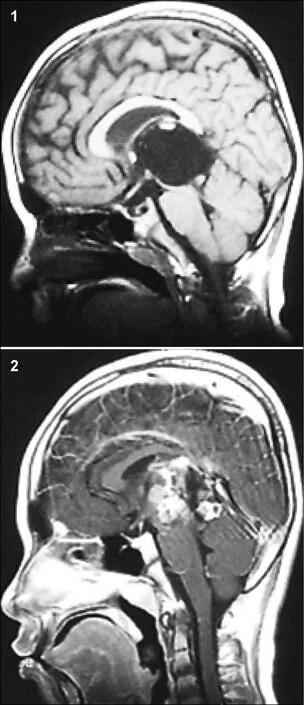

A space-occupied cystic lesion in the rear of the third ventricle was detected in an 8-year-old boy presenting with symptoms of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) and a diagnosis of “cystic lesion” 3 years ago (Figure 1). He underwent a ventricle-peritoneal shunt operation without serum tumor marker test and became asymptomatic soon after the operation. Intermittent regular brain Magnetic ResonanceImaging (MRI) demonstrated no evidence of massive aggrandizement during the following 2 years. Then, 2 months ago, he rapidly developed unsteady gait and confined ocular motor function, followed by acute aggravating clinical symptoms. MRI scans showed that the mass had remarkably enlarged in size and the solid component had become predominant, instead of the prior cystic lesion. Furthermore, the transitional parenchyma tumor was heterogeneously and notably enhanced in contrast-enhanced MR image (Figure 2).

Figure 1 The MRI (2013) showed a cystic lesion in the rear of third ventricle. Figure 2 The MRI (2015) showed the mass remarkably enlarged in size and the solid component became predominant instead of prior cystic lesion.

1.2 Admission conditions

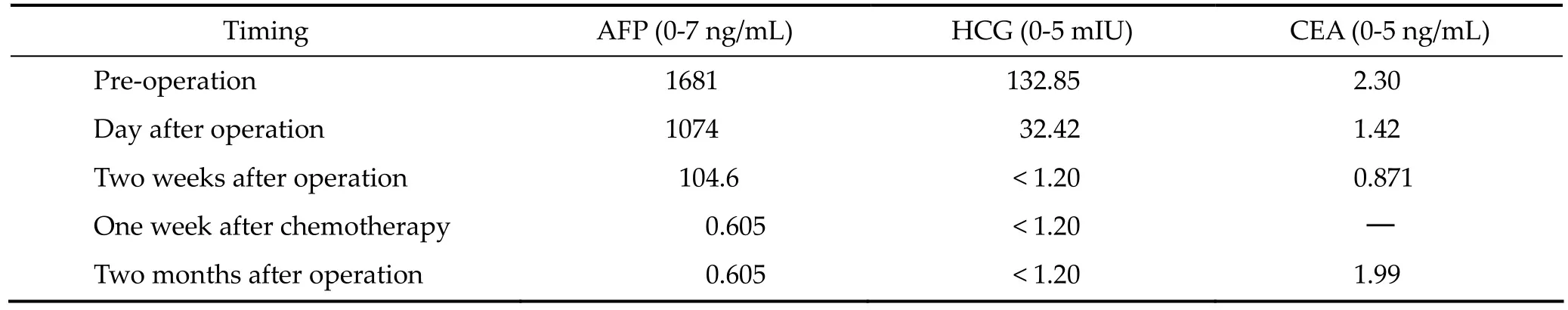

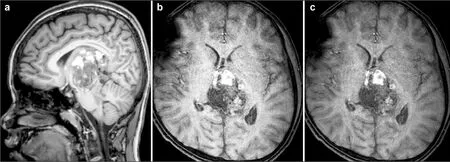

As a result of the large tumor compressing the midbrain, the boy was somnolent, unable to walk, and had jerking and increased muscle tension in all four limbs. Neurological examination revealed left ptosis, anisocoria (left 3 mm; right 2.5 mm), bilateral sluggish pupillary light reflex, restricted eyeball abduction, and bilateral Parinaud Syndrome. Serum tumor marker level investigation showed remarkably raised serum Alpha 1-fetoprotein (AFP) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG ), but carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) was normal (Table 1). Brain MR scans (T1 and SWIp) illustrated enhanced heterogeneous signal and hemorrhagic appearance of the mass (Figures 3a and 3b). Another specific MR (SWIp sequence) scan showed simple blood supply signal on the backside of the tumor capsule (Figure 3c). Diffusion-tensor MR imaging (DTI) described an integrated framework of the corpus callosum and cerebral fornix (Figure 4).

1.3 Treatment procedure

The patient underwent frontal lobe and longitudinal craniotomy via a transcallosal-interforniceal approach. The elongated thalamic intermediate block could be seen. The tumor was noted to have various heterogeneous components, as well as remote hemorrhage with integrated tumor capsule, and was completely removed piece by piece. The patient had a seemingly satisfactory subsequent recovery, except for slight oculomotor abnormality and short-term memory dysfunction relieved within 2 weeks. Postoperative CT scan and MR imaging revealed total resection of the mass (Figure 5). Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy (5 days per cycle) was commenced at the 2ndweek after operation. The patient’s serum tumor marker level declined to normal 1 week after chemotherapy, and synchronous MR imaging showed little hemorrhagic necrotic signal (Figure 6). Diffusiontensor imaging described partial destruction of the nerve fasciculus along the corpus callosum andintegrated framework of the left fornix (Figure 7). The patient returned to school as usual 2 months after the operation. Pathological examination revealed mixed germ cell tumor (Figures 8a and 8b).

Table 1 Preoperative and postoperative serum tumor marker levels

Figure 3(a–c) MRI showed that the brain stem is obviously compressed by the tumor: Figures 3a and 3b showing tumor hemorrhage, and Figure 3c showing the tumor blood supply.

2 Discussion

Intracranial germ cell tumors account for approximately 15% of intracranial primary tumors in children, and there are obvious regional differences[1–4]. Common sites of intracranial germ cell tumors include the pineal region and sellar area, basal ganglia area, cavernous sinus area, posterior fossa, and brainstem[5–8]. Different locations have different symptoms. The tumor may appear cystic, heterogeneous, and full of solids in MRI[4–8]. Intracranial germ cell tumors can also be divided into germinomatous and nongerminomatous germ cell tumors. The latter can be further divided into teratoma, choriocarcinoma, endodermal sinus tumor, embryonal carcinoma, and mixed germ cell tumor[9]. Mixed germ cell tumor is a common classification, in which the internal components of the tumor are complex. Germ cell tumors can rapidly increase in size due to chemotherapy or radiotherapy[9–13]. Tumors that rapidly increase in size without special treatment are rarely reported.

The pathological findings in this case showed a mixed germ cell tumor. There was no obvious change in the imaging features of the tumor since diagnosis 3 years prior. However, after the onset of new symptoms, MRI showed that the tumor composition and volume had significantly changed. It has been reported that benign teratomas can relapse into malignant tumors after total resection, and some scholars have speculated that the pathology may be incomplete[13, 14]. Combining the characteristics of this case and related literature, we speculated that benign tumors may later relapse into malignant ones, and the inconsistent pathologic results are not due to incomplete specimens[15]. It is necessary to examine the serum tumor markers, as the abnormal changes in serum tumor markers are often earlier than the imaging changes[16]. This patient only previously experienced a ventriculo-peritonealshunt, and there was a lack of evidence for serum tumor markers.

Figure 4 Diffuse-Tensor MR imaging (DTI) showed the integrity of corpus callosum and fornix fiber. Figure 7 Diffuse-Tensor MR imaging (DTI) showed partial destruction of callosal fiber tracts, the left dome structure was well preserved.

Biopsy surgery should be avoided as far as possible with this type of tumor[17]. First, there is a high risk of tumor hemorrhage after surgery. Second, the pathological findings of a biopsy are limited due to the diversity of the intracranial germ cell tumors’internal components[9]. In our cases, we have concluded that intracranial germ cell tumors are likely to have a malignant transformation at any time, and this may significantly increase the risk of treatment. Therefore, palliative treatment is not indicated with this kind of tumor; instead, the tumor should be aggressively resected as early as possible. The different subtypes of germ cell tumors can be classified according to the results of preoperative tumor marker tests, which can guide treatment, especially the choice of treatment programs.

Figure 5 MRI showed that the tumor was totally removed with a satisfied result in magnetic resonance imaging findings in the 10th days after surgery. Figure 6 MRI showed that a small amount of hemorrhage and necrosis were observed in the tumor area one week after chemotherapy in MRI findings.

Figure 8(a–b) Pathological examination revealing mixed germ cell tumor.

Tumors located in the posterior part of the third ventricle are more anatomically complex, and operation risk is very high. The most variable factor affecting prognosis of the disease is surgical skill—if the operator is skilled, neurological function will be well protected and good therapeutic effects will be achieved[18, 19]. Preoperative MRI examination and some special MRI sequences are helpful to understand the characteristics of the tumor, the relationship between the tumor and the nerves and blood around it, and the internal blood supply of the tumor. More complete understanding can greatly reduce the risk of surgery.

The most commonly used surgical approach for third ventricle tumors is the corpus callosum dome, which cuts part of the corpus callosum and separates the dome. Zhang et al. believes that cognitive function will be less affected in patients experiencing a corpus callosotomy within 2.5 cm in length[20]. However, our patients have short-term memory disorder after surgery; we speculated that this was related to fornix injury. Diffused tension image (MRI-DTI) sequence examinations can be performed before and after surgery to examine the nerve fibers of the corpus callosum and fornix. This may be helpful for evaluating the patient’s postoperative cognitive function.

In patients with mixed germ cell tumor, the tumor should be resected as much as possible. Our patient’s tumor was totally removed, with an intact capsule. This indicated a good prognosis. Although the tumor was completely removed, tumor marker values were still higher than normal, indicating the existence of malignant tumor cells; therefore, chemotherapy treatment was necessary after surgery. After chemotherapy, there may be necrosis of the residual tumor in MRI scans, and serum tumor markers may return to normal. However, there is much controversy about when to choose chemotherapy for germ cell tumors, since chemotherapy can cause tumor constituent changes[21]. This will then affect the choice of treatment programs. Based on experience, we recommend that only diagnosed patients or tumors with rich blood supply be chosen for chemotherapy treatment, and only as an auxiliary postoperative treatment.

Mixed germ cell tumors are not sensitive to radiotherapy[22], which may cause a tumor’s malignant transformation and abrupt enlargement[9]. This may cause the patient to lose the treatment opportunity and is not recommended as the routine treatment.

In short, for mixed germ cell tumors, combined with Doctor Zhang Yuqi’s long clinical experience[23–27], we make the following recommendations. First, a complete pre-operative examination must be done, especially for serum tumor markers that will aid in correct diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, good surgical technique is key to the treatment of mixed germ cell tumor. The fundamental treatment for nongerminomatous germ cell tumors is surgical removal. Total tumor resection is an important variable affecting prognosis. Chemotherapy is also an important treatment for mixed germ cell tumor; early postoperative chemotherapy is very important. Because of its serious side effects, including bone marrow suppression, low immunity, and changes in the nature of tumor pathology, chemotherapy is not recommended as the first choice, and instead is mainly used as an adjunctive postoperative treatment for tumors with definite pathological results. For mixed germ cell tumor, radiotherapy is not chosen as a common treatment. We also recommend serum tumor marker examination during follow up.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no financial interest to disclose regarding the article.

References

[1] Canan A, Gülsevin T, Nejat A, Tezer K, Sule Y, Meryem T, Gülsen E. Neonatal intracranial teratoma. Brain Dev 2000, 22(5): 340–342.

[2] Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, Fujimaki T, Nakamura O, Funata N, Seto T. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: A clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg 1997, 86(3): 446–455.

[3] Kakani AB, Karmarkar VS, Deopujari CE, Shah RM, Bharucha NE, Muzumdar G. Germinoma of fourth ventricle: A case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci 2006, 1(1): 33–35.

[4] Jorsal T, R?rth M. Intracranial germ cell tumours. A review with special reference to endocrine manifestations. Acta Oncol 2012, 51(1): 3–9.

[5] O’Grady J, Kobayter L, Kaliaperumal C, O’Sullivan M. ‘Teeth in the brain’—A case of giant intracranial mature cystic teratoma. BMJ Case Rep 2012, pii: bcr0320126130, doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2012.6130.

[6] Sanyal P, Barui S, Mathur S, Basak U. A case of mature cystic teratoma arising from the fourth ventricle. Case Rep Pathol 2013, 2013: 702424.

[7] Noudel R, Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P, Litré CF, Rousseaux P. Intracranial teratomas in children: The role and timing of surgical removal. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2008, 2(5): 331–338.

[8] Shim KW, Kim DS, Choi JU, Kim SH. Congenital cavernous sinus cystic teratoma. Yonsei Med J 2007, 48(4): 704–710.

[9] Moiyadi A, Jalali R, Kane SV. Intracranial growing teratoma syndrome following radiotherapy—An unusually fulminant course. Acta Neurochir 2010, 152(1): 137–142.

[10] Bi WL, Bannykh SI, Baehring J. The growing teratoma syndrome after subtotal resection of an intracranial nongerminomatous germ cell tumor in an adult: Case report. Neurosurgery 2005, 56(1): 188.

[11] Hanna A, Edan C, Heresbach N, Ben HM, Guegan Y. Expanding mature pineal teratoma syndrome. Case report. Neuro-Chirurgie 2000, 46(6): 568–572.

[12] Yagi K, Kageji T, Nagahiro S, Horiguchi H. Growing teratoma syndrome in a patient with a non-germinomatous germ cell tumor in the neurohypophysis-case report. Neurol Med Chir 2004, 44(1): 33–37.

[13] André F, Fizazi K, Culine S, Droz JP, Taupin P, Lhommé C, Terrier-Lacombe M-J, Théodore, C. The growing teratoma syndrome: Results of therapy and long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Eur J Cancer 2000, 36(11): 1389–1394.

[14] Shim KW, Kim DS, Choi JU. Mixed or metachronous germ-cell tumor? Child’s Nerv Syst 2007, 23(6): 713–718.

[15] Jia G, Zhang YQ, Ma ZY, Luo SQ, Dai K. The clinical study on the treatment of the introcranial mature teratoma and immature teratoma: 37 case reports. Chin J Neurosurg 2000, 19(5): 334–336. (in Chinese)

[16] Yamashita N, Kanai H, Kamiya K, Yamada K, Togari H, Nakamura T. Immature teratoma producing alpha-fetoprotein without components of yolk sac tumor in the pineal region. Child’s Nerv Syst 1997, 13(4): 225–228.

[17] Sun T, Tian YJ, Liu R, Wan WQ, Luo SQ, Li CD. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of primary intracranial choriocarcinoma in children. Chin J Neurosurg 2015, 31(11): 1094–1098. (in Chinese)

[18] Bruce JN, Stein BM. Surgical management of pineal region tumors. Acta Neurochir 1995, 134(3–4): 130–135.

[19] Friedman JA, Lynch JJ, Buckner JC, Scheithauer BW, Raffel C. Management of malignant pineal germ cell tumors with residual mature teratoma. Neurosurgery 2001, 48(3): 518–523.

[20] Ma ZY, Zhang YQ, Luo SQ. Transcallosal-interfornix approach to remove the tumors of the third ventricle in children. Chin J Neurosurg 2000, 16(4): 207–209. (in Chinese)

[21] Fukuoka K, Yanagisawa T, Suzuki T, Wakiya K, Matsutani M, Sasaki A. Nishikawa R. Successful treatment of hemorrhagic congenital intracranial immature teratoma with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2014, 13(1): 38–41.

[22] Severino M, Schwartz ES, Thurnher MM, Rydland J, Nikas I, Rossi A. Congenital tumors of the central nervous system. Neuroradiology 2010, 52(6): 531–548.

[23] Zhu T, Yu YH, Zhang DJ, Zhang JN, Zhang YQ. Clinical analysis of central nervous system tumors in children, a report of 468 cases. Chin J Neurosurg 2012, 28(1): 8–12. (in Chinese)

[24] Gong J, Jia G, Zhang YQ, Li CD, Tian YJ, Ma ZY. Early diagnosis and comprehensive treatment for germinoma of sellar region. Chin J Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2012, 17(6): 245–247. (in Chinese)

[25] Wang ZD, Jia G, Ma ZY, Zhang YQ, Yao HX. Long-term recurrence after total resection of intracranial mature teratoma: 2 case report and literature review. Chin J Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2009, 14(1): 18–19. (in Chinese)

[26] Li Q, Zhang YQ. Diagnosis and treatment of intracranial germinoma. Chin J Neurosurg 2008, 24(6): 479–480. (in Chinese)

[27] Wu MC, Luo SQ, Jia G, Ma ZY, Zhang YQ. Intracranial nongerminomatous malignant germ cell tumors. Chin J Neurosurg 2006, 22(4): 199–203. (in Chinese)

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年1期

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年1期

- Translational Neuroscience and Clinics的其它文章

- Looking for positive viewpoints for Alzheimer’s caregivers: Case evaluation of a positive energy group

- Effects of the APOE ε4 allele on therapeutic response in Alzheimer’s disease

- Repairing skull defects in children with nano-hap/collagen composites: A clinical report of thirteen cases

- Effects of regional cerebral blood flow perfusion on learning and memory function and its molecular mechanism in rats

- An association between the location of white matter changes and the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease patients

- Effects of aging on working memory performance and prefrontal cortex activity: A time‐resolved spectroscopy study